]>

CHAPTER 12

This “telephone” has too many shortcomings to be seriously considered as a means of communication. the device is inherently of no value to us.

western union Internal Memo, 1876 (the company subsequently

declined to Purchase the new Invention for $100,000)

CONTENTS

Chapter Objectives

Introduction

New Markets, New Models, New WWWorld

The Digital Value Chain

The Changing Value Chain

A Day in the Life of Richard Conlon

Disruptive Innovations

Industry Responds to the Technological Challenge: Value Chain Systems

Summary

What’s Ahead

Case Study 12.1 A Case of “B and C”

References

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

The objective of this chapter is to provide you with information about:

- The digital content value chain

- The changing value chain

- Power to the people: End-users control commercial content transactions

- Content copyright protection and the value chain

- Disintermediation: Cutting out the other guy (company)

- Disruptive innovation and the media industry

- Responding to the challenge

INTRODUCTION: NEW MARKETS, NEW MODELS, NEW WWWORLD

The media industries bring together technology and creativity to produce con-tent that touches the minds and hearts of nearly everyone in the world. These experiences are valuable to people for the information they learn and the emo-tions they feel. Experiential value for consumers is transformed into economic value for the media organizations that make and market content.

It takes a complex set of synchronized activities to bring content products into being and to deliver them to the customer. At each stage in the process, some value is added to the material. The writer brings concepts and a script; the pro-ducer offers vision and management ability; the director of photography and special effects producer bring images to life; marketers build demand for the work, and so forth.

When technology changes, the processes of bringing value to content products also adjust. In the last two decades, almost every aspect of the technology has become digital, including production equipment, computer-generated imag-ery (CGI), and the Internet and other networks. Thus, it is no surprise the pro-cesses to create and bring content to market have transformed as well.

Another key development is the increase in the speed and ease of communi-cation. Improved communication makes it possible for media enterprises to participate efficiently in more markets. Beginning with the formation of the radio industry, early broadcasters marketed programs to listeners and on-the-air commercial time (or avails ) to advertisers. This market structure is called a two-sided market, which brings together two different types of consumers, requiring a strategy for dealing with each market.1 For example, television viewers are one market for broadcast, cable, and satellite networks and opera-tors. They develop business plans for attracting, retaining, and bringing in revenue from the audience. Their second market is advertisers, who want access to those viewers. Content companies develop a second, different busi-ness model to address this market as well. Some companies sell products in multiple markets, facing what are called n-sided markets. Similarly, they develop products and strategies to satisfy the needs of all their customer groups.

THE DIGITAL VALUE CHAIN

Value means the relative importance, worth, or merit of something. In business, value generally refers to economic value , which describes how much someone will pay for a given property, product, or service. As beauty is in the eyes of the beholder, so economic value is in the pockets of the payer. Thus, the value of a company’s product or service is determined by the willingness of consumers to pay for it.

Issues of how companies could increase the economic value of their offerings to consumers came to the forefront with Michael Porter’s 1985 book, Com-petitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance.2 There are other methods used by managers to reach decisions about their business strategies. However, it is rare to attend a media industry conference or convention with-out hearing about the value or supply chain.

Porter coined the term value chain to describe a generic set of activities under-taken by an organization to create and add value. In the media industry, the content value chain includes these stages: development, preproduction, production, postproduction, marketing, and content delivery. Specific prod-ucts call for a tailored value chain, so the chain for creating a Web site might be: conception, planning and flowcharting; page wireframe modeling and mockup; user interface design; and content creation and image acquisition.

FIGURE 12-1 Generic digital content value chain. Source: Based on graphic by Dinesh Pratap Singh, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 3.0.

In Porter’s general model, the four top rows shown in the figure are support activities - firm infrastructure, human resource management, technology, and procurement. They do not add value in and of themselves, but provide support to the activities that do:

- Firm infrastructure: Organizational processes, procedures, and culture; control systems

- Human resource management: Recruiting, hiring, development, and training

- Technology: Information technology and coordinating communications

- Procurement: Locating and contracting for the resources needed to create, market, and distribute the company’s finished products

The five columns at the bottom of the figure - inbound logistics, operations, outbound logistics, marketing and sales, and service - are the activities that cre-ate and add value to the organization’s offerings in the marketplace. The generic illustration of the value chain looks deceptively simple, but keep in mind that there may be hundreds of companies and thousands of individuals involved in the overall effort, and a large number of them in any one of the activity categories. Furthermore, there also may be a multitude of consumers lurking behind each label. For example, the first customer for “inbound logistics” is the producer or the studio. Although the activities add value to the end consumer at a later point in time, it is a different level of value than occurs at the earlier point.

The idea behind the value chain is for managers to understand how each pri-mary activity affects the overall value of the company in the marketplace. Based on that understanding, they can make informed strategies to increase that value. These activities, translated into the media industries, appear in Table 12-1.

Sometimes the term value chain is used interchangeably with supply chain. How-ever, supply chain is an older formulation of business process management that emphasized such processes as Acquire, Build, Fulfill, and Support. (Support activities are those required to operate any business: administration, human resource management, and procurement.) Porter’s conceptualization of the value chain extended the supply chain to add the processes of research and development, branding, marketing and sales, and services.

To understand the value chain, consider how much value a movie studio adds to blank DVDs. The final product will retail for at least $15, often more, and will ultimately go on sale for $5 or $10 - but the blank disc itself is worth less than $1. The studio develops and produces a motion picture, markets it, and replicates it on a DVD. Playing roles in this process, dozens of small and large businesses, as well as individual artists and skilled technicians, perform tasks that add value to the final product. All those activities increased the value of the disc as much as 30 times. Chapter 2 introduced the idea of a digital assembly line that allows media companies to create content digitally, from beginning to end. Only live action production takes place in the physical world, and increasingly the action is captured on digital equipment. Even when it is filmed (an analog technol-ogy), the footage is rapidly, almost instantly, transferred into a digital format. Moreover, as the average blockbuster may contain a large number of digital effects, only a percentage of the film is shot on film at the outset. For example, the motion picture Avatar was 60 percent photo-realistic computer generated imagery (CGI) and only 40 percent live-action.3

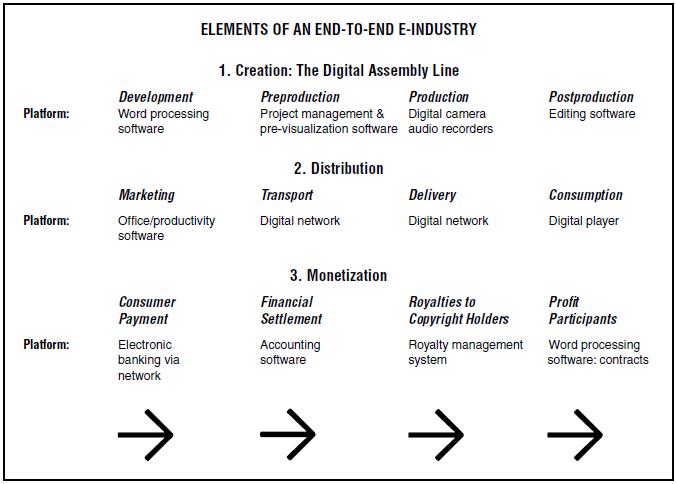

Beyond the digital assembly line for much of digital content - books, maga-zines, newspapers, music, and much television programming - many segments in the content industry have the opportunity to create, market, distribute, deliver, and receive and disburse payments. In other words, they can oper-ate online for most, and perhaps all, of their activities. shows the end-to-end digital platform that has evolved over the past decade to support media industry activities.

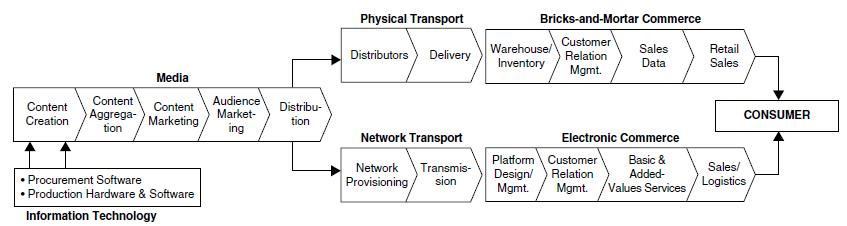

Now let us return to the idea of a two-sided market. One side of the market is made up of media consumers. In this value chain, media is created, mar-keted, and delivered physically and electronically to consumers, as shown in Figure 12-3. In this scenario, people pay for the media they buy to view or listen to on their consumer electronic devices.

However, when it comes to broadcast television and radio, consumers don’t pay. So media companies turn to the second side of their market, advertis-ers. Figure 12-4 shows the value chain for selling access to media consumers to advertisers. In this model, the programming is part of what Porter termed inbound logistics - the raw material of this second value chain.

Value chain analysis begins at the end - with the market.4 The manager looks at market research to determine the characteristics of the overall market and the specific demographic, psychographic, and lifestyle features of the company’s customers (or prospective customers). Based on this understanding, the rest of the analysis can point to how the organization’s activities can bring value to the market, as determined by the end consumers.

The analysis continues with building the value chain: providing the unique detail of each of the five activities, described in the five columns at the bot-tom of Figure 12-1 , that the organization undertakes. Each generic activity is replaced by the names of the business units that synchronize their efforts to prepare, market, and sell finished products, as well as vendor companies and individuals who provide products and services to the company. The list is likely to include hundreds of units, organizations, and individuals - sitting through the credits of a major motion picture shows just how many people are directly involved in its creation.

Once the manager understands all the elements in the value chain, it is possible to analyze how they work together. Porter identified structural factors and dynamic factors. The first structural factor, end markets, has already been examined. The analysis proceeds with a look at the other factors, as described in Table 12-2.

At this point in the analysis, the manager already knows a considerable amount about how the organization gets products to market. Porter also looked at how value chain activities affect profitability, pointing to two key ways the analysis can lead to success: cost advantage and differentiation. A lower price makes a product more attractive to consumers; differentiation makes a product unique, able to attract customers who cannot get these specific features from otherwise similar products.

Organizations can examine the value chain carefully, seeking to reduce expen-ditures at every possible point. They may look at saving by aggregating pro-curement, using their facilities more efficiently, negotiating with vendors and suppliers for lower prices, and many other cost-reducing actions. For exam-ple, a studio can centralize all the DVD manufacturing in a single company, demanding a volume discount.

They can perform the same kind of analysis by looking at how they can intro-duce unique features at various points in the value chain. This strategy is par-ticularly important in the content industries because of the phenomenon of hits and blockbusters. A motion picture starring Brad Pitt is more likely to rake in profits than one starring an unknown actor. A high-priced market forecast report by technology and new media guru Esther Dyson will appeal to decision-making executives more than a similar report written by an unknown marketing professor from a small college.

THE CHANGING VALUE CHAIN

The multiple impacts of technological innovation are the primary sources of transformation to the media value chain. The reach and speed of communi-cation networks, including the Internet, wireless, and mobile; more power-ful handheld devices, such as the iPhone and palmtop computers; and faster, more powerful processing in computers, video cameras, and audio recorders all combine to affect almost every aspect of how media industries operate. Figure 12-5 shows the way a variety of technological advances affect the con-tent creation portion of the media value chain.

FIGURE 12-5 Impact of technology on the creation portion of the media value chain . Source: Joan Van Tassel.

Word processing makes scriptwriting and revision a bit more efficient but does little to change the hard work creating original content in the development stage. Previsualization software, known as previz , replaces the script breakdown and storyboard processes that, in the past, were completed by hand. It increases efficiency to preproduction tasks and provides a solid foundation for the next stage of production.

But the real impact on the value chain is yet to come - cameras, audio records, desktop editing, and digital effects software change the economics of media companies by putting the means of production in the hands of consumers. Two decades ago, this equipment cost hundreds of thousands - even millions - of dollars. Skilled workers spent lifetimes acquiring the specialized skills to operate the various types of machinery that was needed for both audio and video production and postproduction. Today, hundreds of thousands of peo-ple have equipment that allows them to make sophisticated AV content. They may not be able to replicate the quality of Hollywood productions, but as the next section will show, the bar may not be set quite as high as it used to be.

The next portion of the media value chain is the one that has rocked the world of all the media industries - distribution. In the past, this stage was absorbed into marketing and the way content made its way to consumers was taken for granted. People who wanted to see movies went to the theater or rented tapes. People who wanted to watch television turned on the TV set. Listen to the radio? Turn it on. Read a book? Go to the bookstore. In other words, the dis-tribution could be taken for granted, because each legacy medium had its own dedicated form of distribution. Today, consumers can see a movie on at least five different devices, read a book, listen to the radio, or complete computer tasks on at least three devices.

Figure 12-6 Distribution has gone from being an almost invisible commodity to a key way for companies to gain competitive advantage through increasing the value of their offerings to consumers. Content providers that give consumers what they want, when they want it, where they want it enjoy a competitive advantage in today’s marketplace. An example of how it works was the Obama campaign’s new media efforts in the 2008 presidential election. By sending messages via the Internet, social networks, Twitter, iPhone, texting, and email - as well as through traditional mass media - Obama was able to connect with the people who preferred those channels of communication and form a stronger bond with them than would have been possible through traditional channels alone.5 shows how technology affects the distribution activities of media companies. Here, it is not so much processing speed (except in consumer devices) as it is connectivity - the Internet and other content-carrying net-works. Consumers can use peer-to-peer networks and viral email to send content around the world in nanoseconds, which forces media companies to distribute and monetize their products as fast as possible - a motion picture, a song, a digital book, an article - because they’re almost as perishable as a head of lettuce or a bouquet of roses. Global distribution has stimulated alliances and partnerships between the largest media companies and regional and local entertainment managers and creatives to co-develop and co-produce material for such markets.

FIGURE 12-6 Effects of technology on the distribution portion of the media value chain. Source: Joan Van Tassel.

The need for speed pushes back into the marketing phase so that products are often released at the same time around the world, demanding global market-ing support. Many media companies partner with local experts to execute some aspects of their marketing plans, in addition to co-creating content that will appeal to disparate geographies. These efforts are both driven by and made possible by communication networks underlying the constant contact and close coordination such work requires.

Technological changes in distribution both increase and reduce costs. Trans-port and delivery over digital networks reduce distribution costs in many cases, because it is so much cheaper to send bits electronically than it is to messenger motion picture reels, produce and ship DVDs, and print and warehouse books. In some cases, it may even be virtually free, as with reports and articles, which can be sent via email.

However, electronic distribution also increases some costs, including the transcoding of content into many different formats. However, the most stag-gering losses have been caused by three conditions that emerge as by-products of distribution over global networks:

- Consumer power over transactions

- Copyright holders’ loss of control over content

- Disintermediation

Consumer power over transactions, sometimes called power to the edge of the net-work , occurs for two reasons. First, consumers have access to more content, vir-tually all the content in the world. They don’t have the 500 channels predicted almost two decades ago - they have an infinite choice of material gleaned from their own searches and the searches of others, preserved in social sites such as Digg, Reddit, Last.fm, IMDB, Rotten Tomatoes, Metacritic, and other social recommender sites.6 In addition, people can now compare product features and prices from many vendors and suppliers, allowing them to choose the lowest cost seller.

These difficulties are compounded by the problem of copyright protection - or, rather, the lack of it - in the digital world. Content must be generated as analog material for consumers to view or hear it. People cannot see streams of bits as other than 1s and 0s. In order to translate the bits into ships, pirates, and gangplanks, it must be visible to the oh-so-analog world of human hearing and sight. Once in analog form, content can be copied, one way or another. And this is a seemingly insurmountable difficulty, at least so far. Engineers are clever, so it is likely that there will be increasingly imaginative ways for media companies to protect their content, but so far, solutions have proved to be elusive.

The fact that there are many roads to the consumer means that media compa-nies no longer have an exclusive path to deliver content to existing and poten-tial customers. The Internet lets writers, artists, musicians, and other creatives reach consumers on their own. The process of eliminating steps between a buyer and seller is called disintermediation. It’s a game that has many players. For example, creatives can disintermediate music labels, publishers, and stu-dios. On the other hand, these large companies can buy their own over-the-air networks, theaters, Internet sites, and concert venues and disintermediate those existing companies. Conversely, large cable and telephone companies can buy their own production companies and disintermediate the studios.

Disintermediation has occurred in many places in the media value chain, even at the retail level. For example, managers of retail operations can communicate directly with sales personnel on the floor, access inventories and sales figures, and manipulate the data to give them a detailed picture of operations without waiting for written reports and summaries. Many people believe this capability has been responsible for the elimination of many middle management jobs, which traditionally involved gathering information from below and preparing it for perusal by higher management.

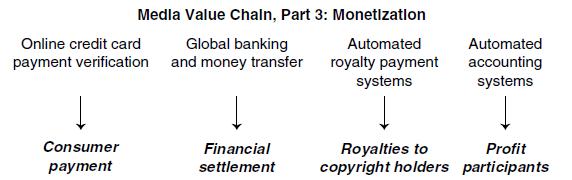

As we have seen, changes in the value chain have not always been positive for the media companies’ activities in the creation and distribution portions of the media value chain. In contrast, technologies in the monetization part of the value chain have been largely beneficial for the largest media organizations. Figure 12-7 shows the development of large-scale systems that automate trans-actions at every level of payment, from the consumer to the seller, and back to copyright holders and profit participants.

FIGURE 12-7 Effects of technology on monetization portion of media value chain. Source: Joan Van Tassel.

A DAY IN THE LIFE OF RICHARD CONLON

Richard Conlon, Vice President, New Media & Strategic Development, Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI) Richard Conlon is Vice President of Marketing and Business Development for BMI. In his position, Conlon is responsible for the planning, development and implementation of licens-ing sales and marketing strategies to grow BMI’s digital licensing business and increase BMI’s, licensing penetration with existing media customers.

He supervises BMI’s New Media Licensing team and marketing effort to radio, television, and cable. During his tenure, BMI has developed licensing agreements with indus-try leaders including MP3.com, Farmclub.com, Yahoo Broad-cast, Live 365.com, and others. BMI also created the Digital Licensing Center, a digital end-to-end online music licensing utility.

After joining BMI in 1994, Conlon started BMI’s New Media department in 1996. Prior to BMI, he consulted to Showtime Pay Per View and held executive positions at Moni-tor Television and the Learning Channel. He holds a master’s in Communications Management from the Annenberg School of Communications at the University of Southern California and a bachelor’s in English from Boston College.

Typical Day

In the volatile world of copyright and digital media, there is no typical day - although most days not spent out of town on business trips start around 6:00 a.m. with a review and response to the previous night’s email on the train on the way into my New York City office. Once in the office around 7:30 a.m., it’s time to review the morning’s digital media news clips online and review briefings for that day’s meet-ings, as well as a once weekly review of the year to date rev-enue and expense reports for the New Media Business Unit. Before I kick off the day, I turn to my spiral-bound notebook

and jot down the key items that I want to accomplish that day as well as items that have a deliverable date to outside clients or internal departments at BMI.

Around 8:30 a.m., I review my calendar for the day and evening with the associate director of administration and discuss any upcoming calendar changes, travel plans, and meetings that need to be set up as well as any depart-mental housekeeping issues that need to be addressed that day.

After that, it’s time for outside meetings to begin - usually the first outside meeting of the day is scheduled for 10 a.m.: working licensees and their attorneys negotiating license for the use of BMI represented music on online services, over mobile platforms, on social networks, and other new media platforms. There are different engagement teams assigned to different pieces of business - usually our leaders of business affairs and financial analysis will join me on these meetings. Lunch may be with a journalist or new media analyst at an equity firm discussing developments in the digital media and forecasts for the future. A typical afternoon would con-sist of another client meeting and working on strategy plans to address the monetization of copyright in the digital media or on conference calls or meetings with other interested parties in the copyright world monitoring development of issues such as the evolving nature of the governance of the Internet.

The digital monetization chain works mainly to the advantage of media giants, at least those that keep control of their own sales. If so, at the start of the revenue stream, when a consumer buys content, he or she receives immediate payment. However, because the royalty payment and accounting systems reside in the large media companies as part of their infrastructure, they can delay royalty and profit participants for as long as it works to their advantage. Disputes between media multinationals and creatives (profit participants), such as actors, writ-ers, performers, and musicians, do not happen every day - but neither are they infrequent. (Of course, if a media company sells through an intermediary, such as many music labels do through Apple iTunes, then the seller is paid immedi-ately and the media company depends on that seller for payment.)

DISRUPTIVE INNOVATIONS

FIGURE 12-9 All of these changes to the media value chain brought about by technological advances, even when they are at least partly favorable, are disruptive to stable busi-ness processes. They make forecasting and planning difficult and, when they have an impact on so many activities, may even make the overall business environment turbulent. Clayton Christenson, a professor of business administration at Harvard Business School, studied innovation in enterprises and developed a theory of dis-ruptive technologies.7 (He later changed the term to disruptive innovations. ) shows how disruptive innovations get their start - at the bottom of the price/performance curve. Notice that the incumbents - the companies making the successful products - have a relatively high price, but they also offer high performance. The higher the performance, the higher the price - buyers get what they pay for. These are excellent companies. They ask their best customers what additional features they want, and they add them. The product develops featuritis , a condition under which it does everything but tuck the customer into bed at night. And the price reflects the cost of all these features.

Now look at the innovator price/performance curve. It starts at a low price - but also a very low performance. Not many customers of the incumbent prod-uct are likely to buy the innovation. But people who can’t afford the traditional product may be willing to spend a little just to get a fraction of performance they find useful.

Here’s an example: the desktop computer. Developed in the period that was the height of “Big Iron,” huge room-sized computers that wrote data to tapes, the first desktop computers seemed mere toys. They had little processing power and less storage. They were good for writing letters and keeping household accounts - and little else. The Big Iron companies barely took notice of these trifling machines that were hardly worthy of being called a computer. Why would they?

But techies, tinkerers, and household bookkeepers and letter writers found them interesting and even useful. These customers were never going to buy an enterprise computer -they constituted an entirely new market of computer buyers who wanted computers for personal use. Over time, as they gained experience with these new gadgets, Apple and IBM made computers that were better - and more powerful. Processors got faster. Memory increased. Apple made them aesthetically pleasing. IBM made them flexible and inexpensive. Pretty soon, desktop computers showed up on enterprise desktops. They didn’t replace huge room-sized computers altogether, but today they are a much larger market than the multiprocessor monsters needed by NASA and the other alphabet government agencies and enormous multinational companies.

Now think about YouTube. A decade ago, it was just about impossible to put video on the Web. It could be done - but it wasn’t easy or inexpensive. As late as 2004, it took an engineer several hours and several phone calls to the site host to configure a Web site and upload video to it. Today, a bright fifth grader can put video on YouTube in minutes.

Consider the price/performance curve of Internet video. The broadcast televi- sion networks weren’t shaking in their boots when they saw the tiny 160-pixel × 160-pixel player, the pixilated video, the muddy audio, and the dumb stuff people uploaded. On the other hand, they weren’t oblivious - they had seen what had happened to the music business, and the industry was abuzz with scenarios for the Death of Television.

So far, this scenario hasn’t unfolded. Instead, as the performance of YouTube increased (the price is still zero), the television networks got on the bandwagon and contracted with YouTube or set up their own video site, such as NBC’s Hulu ( http://www.hulu.com). Flash video, compression advances, and higher speed networks are all rapidly improving the quality of the video viewing experience, and it is making a difference in viewership. According to a June 2009 study, “62% of adult Internet users have watched a video on these sites, up from just 33% who reported this in December 2006. Online video watching among young adults is near-universal; nine in ten (89%) Internet users ages 18-29 now say they watch content on video sharing sites, and 36% do so on a typical day.”8

Figure 12-10 tells the whole story of disruptive innovations. They start small, well below the price/performance of existing products. Then they improve, becoming capable of fulfilling ever more demanding uses. However, even as they improve performance, the innovative nature of the product allows them to keep the price below the incumbent products.

Disruptive innovations pose very real challenges to incumbent companies. They disrupt their value chain activities and, ultimately, their revenue streams. As the innovation improves and begins to encroach on more and more of their markets, the incumbents must respond. One reason the challenge is par-ticularly intense in the media industries is that there are so many disruptive innovations affecting so many parts of the value chain. It has made it extremely difficult, even dangerous, for companies trying to navigate the tsunami of tech-nology that has inundated them in the past two decades.

INDUSTRY RESPONDS TO THE TECHNOLOGICAL CHALLENGE: VALUE CHAIN SYSTEMS

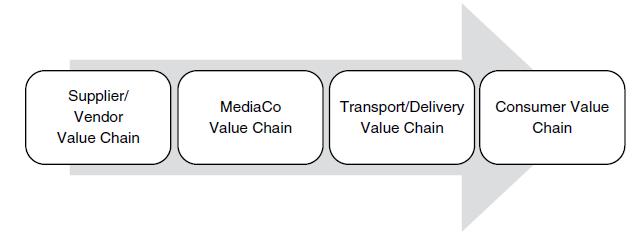

The market is global, the competition is fierce, and the financial stakes are high. One solution available to media companies is to grow. Whether by merger and acquisition, alliance, or partnership, media companies try to put their arms around this new, complex environment by getting bigger. When organizations organize into a series of value chains that include suppliers and vendors, distri-bution channels, and customers, the resulting network of companies is a value chain system.9 See Figure 12-11.

Camp-Building and Keiretsus

One way for organizations to cope with a tumultuously competitive environ-ment is to merge or ally with others whose core business is complementary to their own. If it adds to horizontal or vertical control of a market, the deal is said to leverage the company’s efforts or to provide synergy. In the 1990s, there was a virtual orgy of mergers. According to the Wall Street Journal , in the first half of 1995, there were 649 transactions in the information technology sector alone.10 Some of these mergers were truly blockbuster alliances, including the acqui-sition of the ABC broadcast network by Disney, Viacom’s acquisition of Paramount and Viacom, and the purchase of AOL by Time Warner. At the time, there was considerable discussion about the relationship of transport networks and content producers. It was a question of whether content producers should merge with other producers or with transport providers - called the content/ conduit question. In retrospect, the content/content mergers worked out better than those between content and conduit providers.

This question is likely to come to the forefront again, because content pro-viders need distribution and delivery and conduits need content to distribute and deliver. The organizational culture needed to create unique, one-of-a-kind products that reflect the uncertainty and richness of the human condition is far different from the culture required to deliver pushbutton consistency, reli-ability, and efficiency of the ideal transport and delivery network. Yet these two entities need each other, and on the floor of the digital assembly line, creatives and techies are forging ever closer ties.

When companies join together in a loose alliance to pursue a common set of standards around a product or system of products, it is called camp-building. (Standards are essential to the successful launch of products in which the for-mat of the content must match the technology of the player or display.) Efforts to standardize the new generation of DVD players resulted in two rival camps: the Sony Blu-ray alliance and the Toshiba HD-DVD. Each proponent company had its motion picture studio backers, technology company adherents, engi-neers, and lobbyists that they organized in a camp-building process. Recently, the Sony camp emerged victorious and Toshiba has accepted the Blu-ray tech-nology for its next generation of computers.11

The Japanese keiretsu and zaibatsu may provide a model for the operation of value chain systems. A keiretsu is a group of companies in an alliance that may have some cross-ownership at the top. Often, they are financed by a single bank. A zaibatsu has even tighter links through substantial cross-ownership and jointly executed strategies. This kind of organization may be necessary in a global media environment where many interconnected tasks must be undertaken quickly and nearly simultaneously, including such key activities as marketing and distribution.

SUMMARY

Chapter 12 presented the concept of value and the use of a value chain to show how companies transform the experiential value of content into eco-nomic value for the organization. It examined how and why the content valuechain has changed in the past two decades. It looks at how media enterprises try to harness technological change to their advantage - and to reduce the risks it also brings.

WHAT’S AHEAD

The next chapter looks at how media companies think about their businesses. Managers make business plans and adopt business models that are the blue-prints for their operations as they seek success and profitability. The chapter will cover the elements of media industry business models needed to describe fully how an organization will bring a content product to market.

CASE STUDY 12.1 A CASE OF “B AND C”

In today’s competitive business environment, more and more companies are choosing to move away from the “brick” con-cepts as outlined in this chapter and move toward the “click” concept. Is this always the correct business path? Let’s com-plete an analysis of a company that is attempting to do both and compare with your classmates.

Assignment

- 1 Identify a business that you do business with that has chosen to operate in both the world of “brick” and “click-through.”

- 2. Name the company, the Web site, and detail the business.

- 3. How many “brick” locations do they have?

- 4. When did the “click-through” location launch?

- 5. Explain the advantages and disadvantages for each (i.e., costs, customer service).

- 6. Which portion of the business started first and approximately how long after the opening did they launch the other?

- 7. Name at least two of the company’s competitors. Do they include a “click-through” location?

- 8. How does the company you chose stack up against the competition?

- 9. What advice would you provide this company for the future of its business?

REFERENCES

1. Eisenmann, T., Parker, G. & Van Alstyne, M. W. (October 2006). Strategies for two-sided markets. Harvard Business Review 84:10, 92-101.

2. Porter, Michael, E. (1985). Competitive advantage. New York: Free Press.

3. Campbell, R. & Downing, J. (2008). USAID briefing paper: The value chain framework. USAID: Washington, DC.

4. Van Tassel, J. (March 2009). Politics 2.0. Winning campaigns 4:2, 8-14.

5. Porter, J. (2006). Watch and learn: How recommendation systems are redefining the Web. User Interface Engineering. Accessed July 20, 2009, at http://www.uie.com/articles/recommen-dation_systems/.

6. Christensen, C. (1997). The innovator’s dilemma: When new technologies cause great firms to fail. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

7. Meddin, M. (2009). The audience for online video-sharing sites shoots up. Pew Research Center. Accessed August 3, 2009, at http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2009/13--The-Audience-for-Online-VideoSharing-Sites-Shoots-Up.aspx?r=1.

8. Porter, 1985. Op. cit., 210.

9.. (July 25, 1995). North American information technology activity jumps 76 percent in first half of 1995. Business Wire. Accessed May 4, 2009 at http://www.allbusiness.com/technology/software-services-applications-information/7153791-1.html.

10. Calonga, J. (August 10, 2009). Toshiba exec: “The time for Blu-ray is coming now.” Accessed August 12, 2009, at http://www.blu-ray.com/news/?id=3236.