]>

CHAPTER 11

Contents

Chapter Objectives... 271

Introduction.............. 272

Distribution Revolution................ 273

Bricks and Clicks..... 277

A Day in the Life of Valerie Geller....... 283

Wired Digital Bitpipes.................... 288

Wireless Bitpipes..... 293

Content Management: Transcoding Content into Different Formats for Distribution......... 297

Digital Rights Management............ 299

Summary.................. 301

What’s Ahead........... 301

Case Study 11.1 Create Your Own Digital Assembly Line........................... 301

References................ 302

the speed of communications is wondrous to behold. It is also true that speed can multiply the distribution of information that we know to be untrue.Edward r. Murrow

Edward R. Murrow

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

The objective of this chapter is to provide you with information about:

- Distribution revolution

- Bricks and clicks

- Legacy distribution channels

- Film: Theaters

- Print: Books, magazines, and newspapers

- Broadcast media - Traditional electronic distribution outlets

- Over-the-air local broadcast television and radio stations

- Cable television

- Legacy distribution channels

- Wired bitpipes

- Cable networks

- Telephone company networks

- Computer networks

- Wireless bitpipes

- One-way wireless systems: Satellites (GEOs, MEOs, and LEOs)

- Two-way wireless systems: LMDS, MMDS, cellular wireless broadband (3G) and mobile television

- Content management

- Mass customization

- Personalization

- Digital rights management

INTRODUCTION

The big headaches brought on by digital technologies began with distribution - a previously little-known backwater of the media and entertainment businesses. Sure, that’s where consumers meet content and hand over their crumpled dol-lars at the box office, the counter, and the Web site shopping cart. Yes, distribu-tion is where the money is made. But it’s sadly low on glamour and coolness. No one ever came through the door exclaiming, “I closed this fantastic distribu-tion deal with Telepix today!” like they might have crowed, “I had lunch with Sean Penn today and he’s starring in my next project!”

Nevertheless, nothing has contributed as much to the transformation of the content industries as the disruption of distribution channels and practices. Beginning with the Napster peer-to-peer file sharing that decimated the music industry, every segment has been forced to deal with how to make a profit when consumers can share content without paying for it. But digitization seemed like such a great development at first!

Consider that the content industries differ from many industries because the entire product supply chain, from conception through delivery and consump-tion, can be carried out electronically. (You can’t do that with carrots, cars, or cold storage equipment!) Write content, produce it, prepare it, and deliver it without ever leaving the digital domain. No more paper and ink, celluloid, reels, printing - many of the high costs of getting content to consumers can be eliminated.

Specifically, distributing content digitally makes possible efficient, cost-saving methods of automating the preparation and delivery of content such as transcoding the content from one format to another - repackaging a TV series from broadcast programs to a single DVD. Beyond doing old activities better, digital processing also enables carrying out altogether new actions that were not even possible with analog technologies, such as customizing and person-alizing the content on demand and (perhaps) protecting it from being copied without authorization.

The impact of digital distribution has forced today’s media managers to know a great deal about the technologies of both production and distribution. Just as earlier chapters looked at content production, marketing, and sales, this chapter turns to the means of media distribution from studios and producers, through middlemen, syndicators, and aggregators, all the way to the homes and devices of consumers. (Another way of referring to distribution is the out-put supply chain.)

Even the activities that describe the distribution process are changing. Tra-ditionally, distribution really meant marketing, and the work consisted of negotiating marketing deals that granted distribution rights to another organization. For example, some common types of distribution agreements in the film industry are:1

- Production/Finance/Distribution (PDF) agreements , whereby a studio contracts with a production company and finances the production, while maintaining their distribution rights.

- Negative pick-up deal , where a studio agrees to pay a fixed amount for a completed film. Depending on the details of the agreement, the studio may retain distribution rights or may share them with the production company.

- Presale agreement , usually made between a production company and a foreign distributor to allow the foreign company to distribute the film in a particular country or territory.

Distribution in these agreements really means the sale of rights to distribute - a form of a sale that allows some entity to distribute the film to consumers. Simi-larly, in the TV industry distribution often means selling a content property to a broadcast or cable network, local cable operator or TV station, or a syndicator. In the traditional model, the process stops here. And for a long time, it could stop here, because every industry was associated with its own channel for moving the content to the consumer. Films went to theaters, TV shows to networks and sta-tions, radio programs to over-the-air stations, newspapers to home deliverers or newsstands, and magazines in the mail directly to subscribers or to newsstands.

But like so much else in the content industries, the traditional view of distri-bution stops too short, because the number of content distribution channels has multiplied dramatically, increasing the complexity of getting content to consumers. Legacy distribution channels may still be the most common and profitable in some sectors, but others have seen traditional methods become anemic shadows of their former glory. The music business has been eviscer-ated by peer-to-peer networks and online sales. The newspaper business is experiencing many troubles, because people can read the news on the Internet without paying. In contrast, the motion picture business has been made more profitable by the addition of release windows beyond theaters and network and syndicated television - now encompassing the Internet and mail delivery services such as Netflix.

DISTRIBUTION REVOLUTION

Over the past decade, the proliferation of multiple content distribution chan-nels, brought about by the emergence of global fiber-optic digital networks and the Internet, has opened many paths to the consumer. A company, a content creator, a studio - even a college student - can distribute content around the world in an instant. As we will see, the two-edged sword of anywhere, anytime electronic networks has made distribution a chaotic, thrilling, and dangerous enterprise for today’s media companies.

Given the upheaval, it is easy to think that in the past, little time needed to be spent on distribution beyond contracts and deals, as distribution channels were already established. However, this cozy view of a static past marked by established customs and practices does not address the realities of technological change that marked the media industries throughout the twentieth century as well. For example, in 1891, when Edison Labs demonstrated the Kinetoscope “projector” to show moving pictures, the inventors believed that films would be shown to one viewer at a time. However, the projector quickly became used to exhibit in public theaters to large audiences - the first commercial exhibition of film took place on April 14, 1894, at the Holland Brothers Kinetoscope Parlor at 1155 Broadway in New York. For 25 cents, patrons could watch films that were less than 2 minutes long. According to contemporary reports, the owners took in more than $16,000 in gross receipts, an enormous amount of money for the time.2 Not surprisingly, “parlors” soon opened in London and Paris as well.

By 1911, multiple-reel film enabled long-form movies to be shown, and there were permanent movie exhibition facilities, called “nickelodeons” because they cost 5 cents to attend, in almost every U.S. town.3 This change meant that the people making films had to produce different properties to be successful. More-over, as facilities had only one projector, the projectionist put up a sign that read “One Moment Please” while the reels were changed. Within a short time, a town with multiple nickelodeons would receive only one set of reels. Each the-ater would start the evening’s entertainment at spaced intervals, allowing time for young people on bicycles to speed the just-finished reel from one theater to the next for exhibition. This practice became known as bicycling reels, and the term was still used as late as the 1990s to describe a process where a theater forwards content to the theater next scheduled to display the material. Bicycling continued to be used for syndicated programs in the early days of television.

The examples from the early days of motion pictures underscore the idea that rapid change has been occurring for more than a century - and it will continue into the foreseeable future. Today, the distribution channels of all media are undergoing almost continuous evolution. And when the underlying commu-nication technologies change, every aspect of the medium can change with it, opening up entirely new distribution channels, driving the development of new display devices and altering consumption patterns.

Content distribution reflects the state of technology at any given time. The radio industry first transmitted programs by telephone line and played in hotel lobbies. Broadcast came a little later. Initially, national television programs were transmitted across the United States via coaxial cable and microwave for such live events as the 1953 inauguration of President Eisenhower and the 1953 coronation of Queen Elizabeth; by 1974, many TV programs reached stations via satellite and the consumer by local broadcast signals. Today, televi-sion content comes every which way - coaxial cable, satellite, microwave, and digital telephone and computer networks. Newspapers and magazines were originally posted as broadsheets, then sold on street corners, then from news-stands, and then delivered by boys on bicycles. Now, they reach consumers through the mail, by home delivery, or over the Internet.

For managers of companies that provide content, distribution is more impor-tant than ever because the delivery mechanism has become part of the con-tent’s marketing. Content sellers that want a competitive edge will make the purchase, receipt, and display of their material easy for the consumer, deliv-ering it when and how the customer wants it. On Amazon.com, customers can elect to have books physically delivered to them or download them to a Kindle. Music lovers can buy albums in a music store or download songs from the Internet. Newspaper subscribers can have the paper delivered, buy it from a newsstand, or access it over the Internet. Film buffs may go to a theater, download the movie from the Internet, have it sent to them via Netflix or other service, or rent or buy it from Blockbuster or another local retail outlet.

The necessity to deliver material over multiple channels and networks has raised the visibility of distribution processes in media organizations. In addi-tion, multiple preparations of content products for each distribution channel and consumption device entail a much more complex final packaging process than companies have had to support in the past. As each new channel arises, they have added resources to deal with it on an ad hoc basis. Now media orga-nizations are looking at this disorganized array of distribution formats and pro-cedures to see if they can put more efficient, cost-effective procedures in place.

If an organization enters into a distribution contract, then the actual distribu-tion to the consumer is pushed down to that distributor. Traditionally, there was usually a separation between the companies that engaged in content production, distribution, and delivery: Creatives created, studios and labels marketed and promoted, technical people disseminated, and retail people sold and delivered.

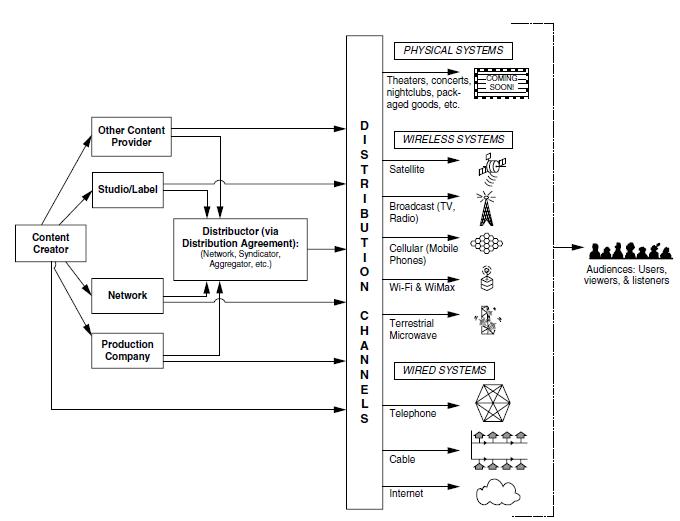

But the growth of distribution channels makes it possible for all participants to distribute directly to consumers. And consumers can redistribute content among themselves via peer-to-peer networks. Figure 11-1 illustrates how legacy channels and direct channels are now available to everyone.

When a company chooses to handle the distribution of content products itself, managers begin by understanding how their prospective consumers want to receive and consume the content - when and where they want to buy it, how and how much they want to pay for it, and how, where, and when they want to consume it. Based on that knowledge, one decision stands over all others - whether to deliver a content product to the consumer in a physical format, like a CD, DVD, book, or magazine, or in a digital, downloadable format - or both. This decision will direct the actions that managers will carry out to disseminate the content and deliver it to consumers:

- Contracting for distribution services that reach desired consumers

- Preparing content for distribution (formatting, customizing, and protecting)

- Scheduling and provisioning distribution services

- Distributing content through a delivery channel

- Delivering content (fulfillment)

- Displaying content

- Tracking content from dissemination through consumption

- Handling consumer relationships (customer care)

BRICKS AND CLICKS

Bricks and clicks is a light-hearted way of pointing to the division between physical and electronic delivery of goods, as shown in Table 11-1. The bricks, sometimes expanded to bricks-and-mortar, refer to buildings and the entire apparatus of retail physical supply lines - stores and warehouses, parking lots, trains and trucks, forklifts, inventory, shelf stockers, shelves and bins, counters, cash registers, checkers, and baggers. Most products necessarily come to con-sumers via physical means: pianos, peanuts, machined parts, and panel trucks.

Clicks won’t take over everything in the physical supply chain, but they do replace many elements of it - retail buildings and associated costs, in-store personnel, checkout lines, and cash registers. Indeed, the entire payment mechanism is replaced by clicks. Warehousing of inventory can stay with the producer or go no further than a distributor warehouse operation, with prod-ucts shipped directly to the consumer. Table 11-1 is a compendium of the dif-ference between bricks and clicks.

For content distribution, each domain has its advantages and disadvantages. The retail world allows face-to-face contact between buyer and seller, engen-dering greater loyalty. In the long run, physical distribution is more costly. The costs of producing copies of motion picture prints, books, magazines, and newspapers are significant. Overproducing packaged content for retail sale leads to expensive returns of product. Underproducing it means lost opportu-nities to make a sale or establish a long-term relationship with a customer.

Many consumers prefer electronic purchase and download of content - it’s instant gratification from a 24/7 store. Electronic distribution of content is also more efficient, but it may entail significant startup costs. It is also difficult to prevent consumers from redistributing the material to millions of their online peers, at a cost that can far exceed any possible savings from greater efficiency.

However, in the end, the physical and electronic worlds are inextricably tied together. For example, even now all of the information that surrounds physical products takes place in the electronic domain, and people in the physical goods industries need to master both domains. The product may be delivered in the physical world, but the design to create them and the promotional efforts to sell them take place in the electronic one. Similarly, all electronic content has its orig-ination in the physical world, which includes computers, servers, cameras, draw-ing tablets, and so forth. Most persuasively, content may be digital, but human eyes and ears are analog, so all material must ultimately translate into the analog, physical domain if it is to be viewed by and listened to by media consumers.

The next sections look at traditional physical media distribution channels, then turn to analog and digital electronic channels. Finally, we’ll explore new, as yet over-the-horizon wired and wireless media platforms that will support emerging channels.

Legacy Distribution Channels

The traditional distribution channels came into existence to support mass media as they emerged in the twentieth century. We all know them: They include motion pictures and theaters, broadcast media and local stations and cable systems, newspapers, via delivery and newsstands, and magazines, via mail and newsstands.

Film: Theaters

Studios usually distribute their own films through a specialized arm of the company. Independent producers may sign them with studios or with indepen-dent distribution firms. Distribution fees average between 32 and 40 percent of the gross box office revenues. Of course, if another arm of the studio is the distributor, then the studio pays this fee to itself. But independent producers can expect to make very real payments to distributors.

Once the deals are signed, the task of bringing the motion picture to consum-ers begins. The first decision the distribution organization makes is whether it will mount a wide release to reach a large audience from the start, or a platform release , a niche-to-wide release strategy that places the picture in a few theaters and building to a bigger audience through word of mouth, or a release that is somewhere between these two tried-and-true strategies. In the niche release, the distributor identifies audiences that are specifically interested in the genre or topic. The film is released in a small number of theaters, often only in urban areas, supported by local newspaper advertising. If the film generates inter-est and word-of-mouth “buzz,” the studio expands the picture to additional screens, testing to see if it can attract a larger audience.4

This is a familiar story for garage band musical groups. Like the term suggests, the group begins by playing together in someone’s home or garage. It then

The country rock band the Cowboy Junkies was formed in 1985 in Toronto, Canada, by siblings Margo (vocals), Michael (guitar, songwriter), and Peter (drums) Timmins and friend Alan Anton (bass). The Junkies first performed publicly in local Toronto clubs. The group’s first album was recorded in the Timmons family garage. Their second album, recorded in 1987, in one day with one microphone, at Toronto’s Church of the Holy Trinity, attracted wider attention. In 1988, the album was named by the Los Angeles Times as one of the ten best albums of the year. Wide to niche: start with a big splash and reexpress for ever smaller audiences.5

moves to local venues and then catches on and attracts a large audience. A good example is the Cowboy Junkies, as described in the box.

Wide to niche is the blockbuster-or-hit strategy. It works well for multinational companies with big production, distribution, and marketing budgets. In the film business, the wide release is the most common, in which studios book the picture into several thousand theaters, sometimes in international venues as well as domestic theaters. The marketing effort can generate good sales for one or even two weeks, but then the product must have genuine appeal. If it disap-points early audiences, even an enormous marketing and promotion budget may not enable sustainable success. The same scenario holds true for new TV programs, CDs, and books - all those hit-driven content products.

Distributors reach a release strategy by looking at the performance of similar films released previously. They also consider the potential audience for the picture, including their demographic characteristics and where they live and work. Based on that information and analysis, the distributor sets out to match the marketing plan for the prospective audience with the availability of theaters and screens.

Once there is a decision about the number of screens, the organization will strike (make) enough prints of the film to execute the marketing plan, because the distribution of films still occurs in the physical domain. The distributor then messengers the prints to theaters. The physical distribution of motion pictures is a major budget item. There are more than 6,200 theaters that house more than 40,000 screens.6 The average cost of a print is between $2,000 and $3,000,7 and every theater showing the picture needs a print; multiplexes may require more than one print. As an example of the scale of costs, to distribute The Negotiator , starring Samuel L. Jackson and Kevin Spacey, Warner Bros. spent $12.32 million for “prints, trailers, dubbing, customs, and shipping.”8

In addition, the theater owner gets a percentage of the box office revenue. Agree-ments between distributors and theater owners (exhibitors) have flexible terms that change over time, called sliding-scale agreements.9 In the first week or two, the distributor may receive as much as 90 percent, with a guarantee of minimum rev-enues, the floor , after the exhibitor’s expenses are met. As time goes on, the agree-ment may provide the exhibitor with a greater percentage, up to 30 or 40 percent. (Exhibitors may make the greater part of their income from concession sales of popcorn, soft drinks, and candy. As one exhibitor executive said, “The profit mar-gin on popcorn is enough to make a grown man cry with joy.”)10

Slowly, the motion picture industry is moving to digital cinema. As of mid-2008, of the world’s approximately 100,000 motion picture screens, about 6,300 of them were digital.11 Digital distribution and display will eliminate celluloid reels, physi-cally delivered to theaters and shown through mechanical projectors, and replace them with electronic data streams, delivered over networks to servers and played out to be displayed by digital projectors. Producing pictures on analog film may well extend for a number of years after the adoption of digital distribution. Accord-ing to a postproduction facility executive, “It will be a long time till the hundreds of thousands of cinemas worldwide adopt the digital technology, which is expen-sive and whose equipment is short-lived. Furthermore, even if 35 mm print goes away eventually, filmmakers will want to originate projects on 8 mm, 16 mm, and 35 mm or 65 mm film for a variety of reasons from ease of use to look.”12

Print: Books, Magazines, and Newspapers

With their centuries-long history, nothing is more “legacy” than books, maga-zines, and newspapers. Printed materials have been produced mechanically with expensive, precision equipment, using paper and ink - until now. Digital distribution of formerly printed products is proceeding at a rapid rate - Inter-net readership of newspapers reached an all-time high in 2009.13 According to the Digital Future Project, Internet users spent 53 minutes per week reading newspapers online, compared to 41 minutes in 2008. Moreover, 22 percent of users reported that they dropped subscriptions to magazines or newspapers in favor of accessing the articles online.

One factor that has kept printed publication alive is the lack of portability of digital versions. People like to read them on public transportation, outside, and in restaurants and other public places. Advances in technologies to allow portable digital reading continue to emerge, including the Amazon Kindle, the Sony Reader, the Samsung SNE-50K, and a dozen other such readers that allow users to download material to read on the go. Current challenges facing the adoption of digital readers are extending battery life, improving readability, especially in outdoor and bright light, and cost. Farther out on the horizon is digital paper , which will use changing digital ink to reflect downloaded material and allow users to read in a manner similar to today’s printed material.

Over-the-Air Local Broadcast Television and Radio Stations: Centralizing Broadcast Operations

The broadcast industry has already made the transition to digital distribution. In the process, the entire landscape of broadcast changed. For nearly a century, radio was largely local; television was also primarily local from its inception in the late 1940s. Today, both these media are largely national entities, offering programming to an ever-larger percentage of the total U.S. audience.

The consolidation in the media industry had many causes, but the result is that most radio and television stations are owned by broadcast groups - there are few family-owned stations left in the United States. The centralization of broadcast operations, including the distribution of programming to the consumer, occurred as part of the transition to digital television transmission.14 Centralizing broadcast operations emerged as a way to reduce the cost of the transition - a case where one innovation brought about another. In the case of digital television (DTV), dig-ital distribution actually brought about a change of much of television technology and many of the ways broadcast companies worked and organized themselves.

For example, as broadcast groups that owned multiple TV stations prepared to invest in the redesign of their physical plants to comply with the government-mandated transition, they became aware of the potential for reducing costs by building one master control room in one location rather than several of them, one in each station. Similarly, they realized they could carry out many tasks just once by putting the results of the job in a centralized, computerized traffic system. Such jobs include producing promos, inserting spots in a program stream, and preparing news and weather graphics for use by all stations, rather than perform-ing these tasks at each station. They could also centralize billing, logs, and many other back-office functions, bringing considerable savings through reducing staff.

The process of centralizing broadcast operations has moved jobs from the local station into the broadcast group. In particular, many managers are likely to work at group headquarters rather than at the owned stations. However, the jobs that are moved depend on which tasks are centralized.

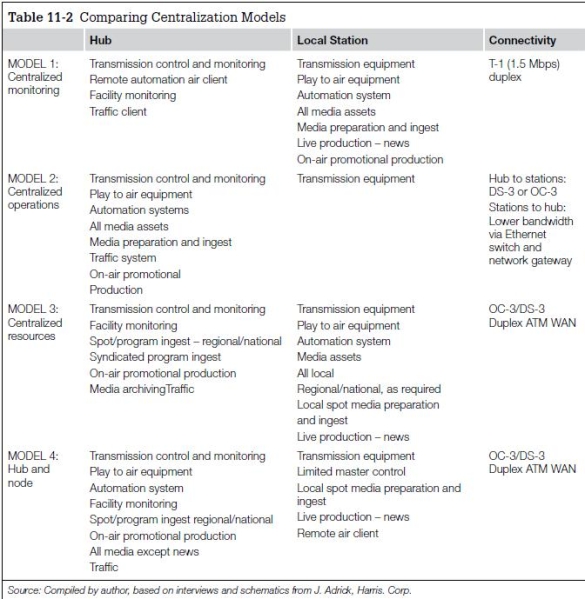

There is a spectrum of centralization that ranges from almost total centraliza-tion to very little. On the whole, radio broadcast operations are more cen-tralized than television - on the ground in the local market, radio broadcast groups may only have a computer server and a transmitter, with everything else centralized at a headquarters facility. (The central facility is sometimes called the NOC , the Network Operations Center.)

Similarly, some television broadcast groups that own several stations in the same region have centralized almost everything, leaving only the local transmit-ter, news operations, and sales. Television groups that have high bandwidth and personnel costs may choose to centralize personnel to allow greater efficiency and reduce staff, while moving material over lower-bandwidth channels. Other television groups whose holdings may be scattered centralize programming coming from the satellite and forward it to the stations, leaving most other func-tions at the station level. In particular, most network-owned and -operated and affiliated stations continue to have a large news organization in major markets and at least a small news presence even in small markets. Managers who want to succeed in broadcast companies need to understand the decisions their company makes about how to structure its operations and why they make them the way they do. They need to understand that as new technologies come on the market, it may affect the way the company operates, driving changes that affect jobs, processes, and profitability. There are several models of centralization, as shown in Table 11-2.

Cable Television

Like local over-the-air television stations, the owners of early local cable systems often lived in the same market, known as mom-and-pop systems. Today, nearly all local cable systems are part of larger companies known as multi-system operators , or MSOs. The local headend receives satellite signals, gathers them together ( multiplexes ), and pushes them out to subscriber homes. Han-dling analog signals is relatively simple and most cable headends automate the process. As signals come in, they are demodulated, scrambled, multiplexed, amplified, and demultiplexed for transportation to neighborhood nodes. If they are scrambled, the decoding will be done by the subscriber’s set-top box.

Yesterday’s cable networks were one-way, just shuttling cable networks to sub-scribers. Today’s systems are much more complex, because they are two-way communication networks as well, providing Internet access, video on demand, and telephone service as well as cable TV. Content producers, networks, and middlemen do not have to concern themselves with the details of transporting their material over cable networks, because cable system engineers have worked out the mostly automated process. However, they may need to pay for all or part of the costs for the satellite feed to headends, particularly if they are distributing material they hope the cable system will run. Such content might include info-mercials, video news releases, or public service announcements ( PSAs ) . Executives who work for cable companies and other content transport net-works do need to understand how their company transports content in some

A DAY IN THE LIFE OF VALERIE GELLER

Valerie Geller, President, Geller Media International; Broadcast Consultant; Author: Creating Powerful Radio

Valerie Geller called her first talk radio show at age seven. The host of the program was complaining about kids who’d made too much noise at a restaurant. His idea: “Keep ’em quiet or leave ’em home until they’re 18.” Geller picked up the phone and told the host that the lives of most kids were so restricted, and that every aspect of a child’s life is somehow controlled by his or her parents or other adults - the one thing a kid could do for freedom of expression (and to have fun), was to make noise, so could he please stop talking like that and leave the kids alone? Her message: “Let them make noise.”

And so it began. Her experience in broadcasting prior to becoming a consultant: Geller was program director of WABC Radio in New York City, executive producer of KFI in Los Angeles, news director of K101 in San Francisco, news reporter for KTAR in Phoenix and K-Earth-101-FM in Los Angeles, and a talk show host at KOA in Denver and at WPLP in St. Petersburg, Florida.

Over the past 20 years, Geller’s worked with more than 500 stations in 30 countries, and is considered one of the top broadcast consultants in the world. In 1991, she formed Geller Media International, with a client list that includes NPR sta-tions, CBS stations, the BBC in the United Kingdom, the ABC in Australia, Swedish Radio, and many more. Radio Ink Mag-azine named Geller one of the “50 Most Influential Women in Radio.” An in-demand workshop and seminar leader, Geller is a popular keynote speaker at conferences for broadcasting, news, information, and new media and podcasting. She also lectures at NYU Film School and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism in New York.

A native of Los Angeles, Geller currently lives in New York City. But the work developing and training (and finding) on-air personalities, news reporters and anchors, producers, and programmers takes her around the world. Geller has trained and worked with some of the top people in the business, and has served on the board of directors of the Associated Press and NORCAL Radio & TV News Directors Association and is the author of three books about radio, including:

- Creating Powerful Radio - A Communicator’s Hand-book for News, Talk Information & Personality (M Street Publications, 1996)

- The Powerful Radio Workbook - The Prep, Performance & Post Production Planning (M Street Publications, 2000)

- Creating Powerful Radio - Getting, Keeping & Growing Audiences for News, Talk, Information & Personality - Broadcast, HD, Satellite & Internet (Focal Press, 2007)

- A new book, Beyond Powerful Radio - A Communica-tor’s Handbook for the Internet Age , will be available from Focal Press in 2011.

For more information on these books, see http://www.creatingpowerfulradio.com. For more information on Geller Media International, see http://www.gellermedia.com.

Describe a “Typical” Day: If a Student Were Spending a Day with You on One of Your Busiest Days, What Could He or She Expect to See and Experience?

This is a tough question. I once had a film crew trail me - after shooting for three and a half days, they finally felt they’d cap-tured an “average” day. While I live in New York City, I travel the world and over the past 20 years I’ve worked with more than 500 stations in 30 countries. Anywhere people want to learn the powerful radio techniques, and can bring me in, I’ll go. It was easier to answer the question about “What is a typ-ical day?” when I programmed a local radio station (WABC in New York) or was a news director at a major market station. A typical day was more structured, beginning with meetings with show hosts, news reporters and producers, marketing and sales and accounting, and other department heads, work-ing to find and develop on-air talent, regular lunch meetings or breaks, basically all the tasks involved in running a station. But now I work as a consultant, and no two days are alike. I write books, lead training seminars and workshops, give speeches and coach individuals, lecture, and travel the world. That’s part of the fun and why I love consulting: it’s never routine or boring and you get to see the world, meet, talk with, and work with fantastic, creative, and talented people, experience other cultures. So a “typical day” may have me waking up in Moscow, Singapore, Sydney, Nairobi, Los Angeles, Toronto, Mexico City, Stockholm, or London, working with radio and TV stations on-air, programming, news, and producing staffs.

How Does Your Typical Day Begin?

No matter where I am my day usually starts with a strong cup of coffee (in Europe I got hooked on Italian coffee, Turkish coffee, or just any great coffee - and now if I don’t get a great cup of coffee in the morning, somehow my brain just doesn’t get going the same way!). I wish I could be a great role model and tell you that I exercise (a long-term goal), but that wouldn’t be honest. I have yet to start an exercise routine and stick to it in the morning.

When I open my email, even at 6:00 a.m., my message box is filled - usually from broadcasters in Europe, where the day has long been under way when we’re just getting started in America or from clients in Australia where their day is wrapping up when it’s morning here. These could be anything from requests from managers looking for talent for their stations or any one of a myriad of small “put-out-the-fire” problems, to larger issues involving format or manage-ment issues, research, or strategic planning.

What Is the First Thing on Your Agenda?

Each day is a bit different, though in looking over the past few months of days on my calendar - it looks like many days typi-cally start either with an aircheck meeting, a programming or news meeting or a conference call with clients. I tend to do a lot of airchecking first thing, as that’s when morning shows get off the air and have the time (and desire and inclination) to review their program.

Whom Do You Interact With?

I work globally and often in languages other than English, so many days, the most consistent person I interact with on a project would be the translator or interpreter, who helps me understand not only what went on air, but also helps put the content into context of the stories and helps me understand the customs and culture of each individual country. I also interact regularly with on-air personalities, those hoping to become on-air personalities, also producers, news directors, marketing and sales staffs, program directors, and general managers.

What Are Some of the Most Challenging Issues You Face? It Looks So Easy!

Because everyone can talk, most people falsely believe this work is easy! But just like a great actor, athlete, or dancer, the great ones just make it LOOK that way! This work takes craft, skill, training, experience, and talent. It’s hard. The curse of our business is that everyone can talk, so everyone thinks this work is easy! But I believe there are NO boring stories, only boring storytellers, powerful storytelling can be taught, and everyone can improve, if people are willing to learn the techniques.

You Can’t Make ’Em Do What You Want Them to Do

There’s a joke: “How many psychiatrists does it take to change a lightbulb?” The answer: “Only one, but the lightbulb has got to want to change.” As a consultant, you can make suggestions and offer ideas and solutions, and while you may have influence, you have no real power. You can never make clients do the things you know will help them. It’s like being a stepmom or substitute teacher. These are not “your kids.” So the hard part is when you watch the train heading off the rails and you know what to do to get it back on track, but the client chooses not to take the advice.

Broadcasting Is Changing

Our industry is in a technological shift and we’re moving away from traditional delivery systems. Attention spans of audiences are shorter, people are busier, and there’s much more information and entertainment out there and available to choose from.

But while our listeners and viewers are getting their information in a variety of ways, the basic principles to get, keep, and grow audiences are the same no matter what the medium and they work throughout the world. Tell the truth, make it matter and never be boring. Inform, Entertain, Inspire, Persuade, and Connect. No matter what the delivery system, if the content is relevant, listeners and viewers will be there. The work I do is to teach methods to help clients create rel-evant and powerful content that works across multiple and changing platforms

Cutbacks and Downsizing of Station Staffs

Even in times of economic downturn or cuts to staffs in the newsroom or at stations, the challenge is to keep the content relevant at all times and to train and teach powerful com-munication and storytelling - with the goal of broadcasters and podcasters creating powerful content. Creativity costs nothing. But it takes time and hard work. And getting, keep-ing, and growing audiences for stations is always hard work and a challenge.

Meeting Our Daily Goals

TV, radio, and Internet content producers have two goals: THE BIG DAY and THE REST OF THE TIME. Coverage of events on “the big news day,” when what’s happening is of such magnitude (weather emergencies, toxic waste spills in the local area, a tsunami, or earthquake, bomb blasts, etc. - where the lives, safety, and well-being of the public are in danger is different from other “regular days of programming”). The “big day” event coverage is special programming, and all broadcasters need to be prepared for those few days each year when the news events occur. On those days, our first responsibility, anywhere in the world, is to “keep our listeners and viewers safe from harm, broadcasting what they need to know immediately to stay safe, and verifying that the infor-mation we’re giving is correct and credible.”

Then there’s the rest of the time, which is most of the time, our job as broadcasters is to inform entertainingly and entertain informatively and keep audiences even when not that much is happening. Our gig is to inspire, persuade, and connect listeners and viewers. My work involves teaching. The methods are in all of the “powerful radio” books and they are universal. Our job as communicators and broadcasters is to be powerful storytellers who chronicle the struggle to be a human being and reflect real life with a microphone. The work I do teaches powerful communication techniques, effective storytelling methods, and how to captivate an audi-ence. The powerful radio principles are:

- 1. Tell the truth.

- 2. Make it matter.

- 3. NEVER BE BORING!

Jetlag

The only other challenge I face - other than the basics of work-ing out of country and culture and language - includes the stress of constant “time shifting,” getting off a plane in a differ-ent time zone, exhausted, and having to be “on, alert, awake, and creative” when you’re completely jetlagged and wiped out.

Describe the Highlights of Your Work Day

When the work works ! Breaking through to broadcasters who’ve been working one way for some time, then try new ideas to improve their work. The “highest” highlight for me is turning on the radio and hearing the personalities and news-casters creating compelling and powerful radio - as they “get it” and begin to work with and embrace these meth-ods. Also of course looking at the ratings and seeing proof of audience growth! The “powerful radio” books and principles are universal and work everywhere. These books have been translated into several languages - and have made their way around the world, Each time the methods prove successful or a broadcaster contacts me saying one of my books has become his or her “bible,” I’m thrilled. It doesn’t get better than that.

How Do You End Your Day?

Well it sounds very boring, but at the end of the day when I’m on the road, consulting stations or working one-on-one with talent, I wrap up the day by writing client reports. (Or making notes, so I can remember details later. It’s good to do while some of the key points of the work we’ve done together and the agreed-upon achievable goals are fresh in my mind.) At the office, at home in New York, you can work 24/7, as my work is international - and it’s always business hours some-where in the world where I have clients. So I have to put the stop to the day. Dinner or relaxing with the significant person in my life, or checking in with friends - when you do this kind of work, sometimes there’s a fine line between work and the rest of your life. I don’t worry too much about that these days.

Discuss Any After-Hours Responsibilities

When I’m on the road, there are those days of course when I’ll have dinner with clients, and continue our day’s work. Then there are other times when I’m so exhausted that I go back to the room and get quiet.

But one of the best pieces of wisdom I’ve ever gotten about this came from another consultant. The advice: “I’ll still work with you this afternoon, but after 4:00 p.m., we have to leave the office. And you have to take me some-where interesting. We can still talk about work, but we have to go somewhere and see something.” That advice has been golden. I’ve seen the “Edge of the World” in southern Nor-way; the “Apostles” in Australia; watched a baby giraffe being born in Nairobi, Kenya; celebrated the Santa Lucia fes-tival and parade in Finland; watched a magical sunset on a deserted beach in the Philippines; had a private tour of Red Square and the Armory Museum in Moscow, Russia; hiked the woods of southern Sweden; sipped tea in the home stu-dio of a nation’s poet laureate; taken a personalized tour of the Louvre with an architect involved in the redesign of the structure; shopped the Christmas Fair in Nuremburg, Ger-many; and much, much more.

What Is a Typical Day?

There’s no such thing, for me; my work encompasses more like three or four separate work lives. If I’m in my New York office, that’s one type of day, that might start with phone calls and email, but end up in a producer meeting, then being picked up in a limo town car heading to the Hudson Valley estate of a local celebrity who’s starting a talk show in the fall, followed up by meeting with executives of a satellite radio company planning a new program.

If I’m attending a conference, speaking or holding training sessions, keynoting a conference, or leading a Creating Pow-erful Radio seminar, Powerful News, or Geller Media Interna-tional Producer’s workshop, that’s a completely “other” kind of day! But when I’m on the road, as a consultant, working with a station either in the United States or overseas, it’s one “typical day” (see following schedule). But if I have to pick a typical “day,” here is what happens when I’m working onsite as a broadcast consultant at a station, on the road.

On the Road - Onsite - Consulting at a Station - Typical Day

5:30 a.m. Wakeup call.

5:45 a.m. Second wakeup call.

6:00 a.m.-10:00 a.m. Order room service breakfast, get dressed, monitor the station - by listening to the morning show - drink some coffee, make some notes. Look at the schedule for the day.

10:00 a.m. Grab my stuff and leave the hotel to head over to the station.

10:20: a.m. Arrive at the station. Grab a cup of coffee and get ready for our meeting.

10:30 a.m.-12:00 p.m. Begin the meeting. We’re doing an aircheck session and one-on-one coaching with the morning show personalities and their team, listening to today’s pro-gram, using the Powerful Radio Aircheck Criteria.

12:00 p.m.-1:00 p.m. Lunch meeting with general man-ager and producing teams.

1:00 p.m.-2:00 p.m. Take a bit of a break, check the email, return a couple of phone calls, write some notes about this morning’s aircheck meeting.

2:00 p.m.-4:00 p.m. Station “Creating Powerful Radio News Seminar” for radio and TV news staff.

4:00 p.m.-5:30 p.m. Goals and follow-up meeting with management staff.

7:00 p.m. Dinner with station’s general manager, program director, news director, and executive producer.

9:30 p.m. Go back to the hotel, then check email, take a hot shower, write up notes for the station consulting report, and call home.

11:00 p.m. Watch local TV news.

11:45 p.m. Try to get to sleep!

detail, so we will discuss them further in the next section. As most content products are increasingly distributed in digital form, they are easily transported on both wired and wireless digital networks. Digital data streams are called bit streams and the channels over which they travel are often referred to as pipes or bitpipes. However, keep in mind that sometimes it is more difficult to move content to a home in a neighborhood on 30th Street in Athens, Georgia, than it is to get it to Athens, Greece. It’s referred to as the last mile problem , and it has cost telephone companies and cable companies billions of dollars to bring high-speed bitpipes to consumers.

WIRED DIGITAL BITPIPES

Cable systems, telephone networks, and computer networks are all examples of wired bitpipes. And they all face a similar challenge: deliver all forms of content - video, audio, text, graphics - in two directions, to and from the consumer. Provide fast, always-on, reliable service at an affordable price. Each transport provider brings existing networks to the table, with its architecture based on the original purposes of the network. As requirements change, they must figure out how to use their networks to address the change or - in the worst case - reconfigure or rebuild their networks. In the past two decades, operators of all three types of networks have had to maintain a continuous schedule of design, redesign, construction, and reconstruction just to keep up with consumer demand.

Broadband Internet

Cable systems began life as broadband one-way systems in which signals ran over coaxial cable. Gradually, operators have introduced fiber optic cable into the backbone, extending it ever deeper into the network. A particularly sophis-ticated and elegant design is the hybrid fiber/coax (HFC) network, conceptual-ized by Dave Pangrac of Pangrac & Associates on the back of a napkin during an airplane flight.15

The HFC design was further refined and implemented by a team led by engi-neer James Chiddix of Time Warner Cable. By carefully thinking through the bandwidth usage, HFC allows every household in a 500-home neighborhood node to have an exclusive channel that carries a unique broadband stream. The term “500-channel universe” came from the HFC network that could allocate a complete channel per household.

Hybrid fiber/coax means that the main “pipe,” the backbone, is fiber optic cable. Usually the wire into the home is coaxial cable , or coax. Almost all cable systems have upgraded to some version of an HFC design. Some cable systems are installing fiber to the neighborhood node to enable an interactive digital TV tier, video on demand, and two-way high-speed Internet services that can grow as demand rises.

Managers who work for cable companies speak the language of broadband systems. For example, try reading this statement out loud: “This 750 MHz (megahertz) system passes 50,000 homes. To provide high-quality VOD (vee-oh-dee), assuming peak utilization of 25%, we’ll need a server that can output 12,500 4-megabit per second MPEG2 (em-peg two) video streams simultane-ously. Network capacity on the backbone will have to be about 50 gigabits per second.” That statement is fairly typical of the way a cable executive might describe a cable video-on-demand (VOD) system. It is easy to decode once people are familiar with the terms:

- The capacity of advanced cable television networks is measured in megahertz of bandwidth, i.e., 550 MHz, 750 MHz, or gigahertz for the largest systems, such as 1 GHz. When a system is described as a 750 MHz or 1 GHz system, the numbers refer to the capacity that can be delivered from the headend to each home or other receiver site, its end-to-end throughput along the downstream path.

- VOD stands for video on demand, a service provided by most large cable systems that lets consumers request video material and receive it right away.

- Peak utilization is the highest usage the system must be able to accom-modate under normal circumstances. The capacity of the backbone must be the biggest part of the system, the sum of the bandwidth available for all the signals that are delivered to and from the neighborhood node, times the number of neighborhoods.

Broadband ADSL (Telephone Networks)

Cable systems began with a broadband system that was only one-way - their challenge was to develop a broadband two-way capability. It was an expensive proposition. Telephone companies began with the PSTN ( public switched tele-phone network ), a reliable two-way communication network, but it was narrow-band, carrying only voice and data. Their challenge was to develop broadband networks - an even more expensive proposition.

The business decisions about transport networks that executives must make to provide content distribution services are complex. Mistakes are costly. Building a high-capacity network in which bandwidth goes unused can cost millions or even billions of dollars. Building a network that is too small, where consumer demand quickly outstrips availability, can cost millions or even billions of dol-lars as those consumers move to another source of content.

Some telephone companies just start over and adopt an HFC design when they build a network designed to deliver TV services. Often this choice involves overbuilding , or creating a separate network that follows the pathways of the existing telephone network, taking advantage of right-of-ways they have already negotiated. However, most telephone companies installed a version of a tech-nology digital subscriber line (DSL) , repurposing their existing networks.

The telephone company that provides service to most residences is called a local exchange carrier (LEC) or incumbent local exchange carrier (ILEC). If the LEC used to be part of old national AT&T telephone system, it might be called an RBOC, standing for regional Bell operating company. In many cities, large companies have the option of receiving telephone service from a competitive access provider (CAP), which are private companies that do not have a govern-ment-established geographical service area. There are a few private companies that do provide residential service; they are called CLECs, competitive local exchange carriers.

The basic telephone line is two wires between the telephone and the telephone company’s central office (CO), sometimes called a branch exchange. Carrying signals and electricity in both directions between the home and the central office, this pair of wires is called a drop, a loop, a pair, twisted pair, copper pair, or a circuit. The local loop is the physical layer of the interface between customers and the PSTN, providing the familiar dial tone, touch tones, or DTMF (dual-tone multi-frequency), and busy signals.

The central office houses one or more switches that transmit each signal toward its final destination. The switch connects the two ends of the telephone call and holds open the path from origination to termination throughout the length of the communication (a dedicated circuit).

If the call is going to another neighborhood telephone, it might be switched directly to the terminated line; if it is within the local area, it will be forwarded to the switch in the central office where the terminated line is located. If it is a long distance call, outside the area of the telephone company’s service area, then it goes to the switch of an interexchange carrier (IXC), a long-distance company. The location at the IXC is called a point of presence or POP.

Digitization has proceeded throughout the PSTN backbone and is now mov-ing into the local loop. DSL technologies come in many flavors; xDSL refers to any or all of them. The various types are ADSL, ADSL Lite (G.lite), RDSL, HDSL, SDSL, and VDSL. Asymmetric digital subscriber line ( ADSL ) is the most common installation in homes.

Some telephone companies that want to deliver multichannel TV and high-speed Internet access built VDSL ( video digital subscriber line ) networks . For example, AT&T adopted VDSL for most of its localities, where it offers U-Verse television and Internet access services. Even though the maintenance is higher for VDSL than it is for HFC networks, many of AT&T’s holdings are in low-density geographies, so it was cost-prohibitive for the company to construct new networks from the ground up. By contrast, Verizon has adopted a fiber network it calls FiOS ( Fiber Optic System ) because many of its systems cluster in the northeast of the United States, where population density is high.16

Computer Networks

When the Internet began, computer networks that delivered content across long distances used the PSTN, the telephone network, to transport content. Because in the early days content was all data, the tiny bitstreams were hardly noticeable in the ocean of voice calls. Now telephone networks and computer networks are interconnected in complex ways - telephone providers often use the Internet to carry voice calls.

Although as consumers, it would be easy to see content distribution over the Internet as free, it isn’t. Yes, you can send emails, photos, even songs and vid-eos without paying more than the monthly cost of Internet access. But private individuals aren’t delivering video or audio content, day in and day out, 24/7. They don’t have customers paying them for flawless, timely delivery who will dispute payment if they have to wait too long.

As a result, companies that deliver content to consumers pay to ensure that the process goes smoothly. Managers spend considerable time and conduct careful analysis to select vendors who supply transport services over the Internet. It’s not easy to find reliable service at an affordable cost because the very structure of the Internet and other computer networks works against easy delivery of very large, time-based files.

Computer networks differ from telephone networks in that they are packet-switched , rather than circuit-switched. A telephone circuit stays open from the beginning to the end of the call. A computer network doesn’t have a circuit at all. Messages are divided into packets - and they are very, very small. Each packet has a header that identifies the message destination and information about the length of the overall message and the position of the packet in the message. The message is held at the destination until all the packets arrive and can be assembled. Then it is delivered.

Each Internet subscriber has a unique address on a local network. Content arrives and goes out through a service provider’s server, which sends and receives mes-sages to and from other networks via a gateway. Routers take messages in, read the network destination with packet sniffers , and forward the packet to the next available destination that is closer to the final destination. Routing information is similarly dispersed. Each router makes a decision about how to forward a packet by referring to a lookup table that identifies the next node to which the packet should be forwarded to move it toward its destination. Lookup tables are loaded by the router itself, based on routing information supplied by other routers or on some kind of human input.

National traffic passes through four network access points ( NAPs ), located in Washington, D.C., New York, Chicago, and San Francisco. Traffic is carried on the Internet in three ways. Peering is an “I’ll carry yours if you’ll carry mine” type of agreement. Although all operators originally peered with one another, in the mid-1990s, small networks were dropped from the agreements and, since then, only the largest carriers peer with one another. The other agreements are called peering payment and transit payment , both of which involve some kind of fee by the larger operator for carrying the traffic of the smaller operator.

The actual architectures of the major carriers is proprietary information - no one knows how the Internet actually works in complete detail. In a router-based network, there is no dedicated connection open for the duration of the com-munication. This connectionless type of network is often represented in graphic depictions of networks as a cloud , a puffy curved entity that sits in the middle of diagrams of network architecture. It really misrepresents the complexity of network connectivity but it satisfies the descriptive needs of managers trying to explain how content will reach consumers.

The Internet does have a hierarchy and some geographically situated elements: NAPs, IXs, MAEs, POPs, ISPs, and users. The top of the hierarchy begins with:

- Level 1: Network access points (NAPs), large interconnection facilities where the largest Internet service providers (ISPs) and network service providers (NSPs) all mount racks of equipment in the same location.

- Level 2: Data emanates in and out of the NAPs along large lines that form the backbone of the network.

- Level 3: The information lands at the interconnection point (IX) of a regional network and then Metropolitan Area Exchanges (MAEs), located in most major U.S. markets.

- Level 4: Data is routed to the local Internet service provider (ISP), which maintains a point of presence (POP) on the network.

- Level 5: Customer premises: businesses and homes.

At almost every point on the Internet sits a server. A Web site is really a software construction that is stored in a server, so when a user “visits” a Web site, it really means that the graphics, text, video, and audio - the content - is transferred to the user’s local machine by a server. Of course, in reality, the user isn’t going anyplace; the bits that constitute the Web site move across the Internet to the user’s machine.

Servers may be huge pieces of equipment, Big Iron, operated by ISPs or large private companies. Or they may be merely user PCs that are software-enabled to dish out data. Whether they are businesses or people in their homes, customers are at the fifth level of the Internet. If the subscriber is a business, then the organization often has a LAN that supports any number of employees, extend-ing the Internet yet further. When a computer is connected to a network, data flows in and out. For many people, this is quite worrisome. Companies are in a position to act on their concerns, and security is manifested in hardware as proxy servers or edge servers. This specialized server maintains a firewall that protects unidentified data from entering the company’s LAN or WAN. By pro-viding instructions to the proxy server, companies can prevent employees from accessing some Web sites such as LimeWire or Facebook.

Companies providing video or even audio will use servers optimized for media. A media server is actually a special-purpose computer that enables commercial media delivery. A customer order comes into the media server; the server locates the desired information in storage, retrieves it, and sends it downstream to the viewer. It then sends a message to the billing software to charge the consumer. The ordered material might include video of movies, television programs, and direct-to-home programs. It may be entertainment-oriented or informational in nature. Other content could be music, games, catalogs, lists, and announcements.

One thorny challenge for media servers is simultaneous flows of a single on-demand video. For example, when a new movie comes out, everybody wants to see the new hit at once. Upward of 90 percent of the traffic could be generated by five or six current hit films. At the video store, all the copies of the popular film are gone and customers have to be placed on a waiting list - by contrast, an interactive system just crashes.

The technology of broadband wired bitpipes has continued to advance, enabling the Internet to grow and expand. From time to time, some Chicken Little will shout that “the Internet is falling, the Internet is falling!” but, so far, it has proven to be scalable and strong, just as its designers hoped. The next section examines wireless bitpipes.

WIRELESS BITPIPES

Wired bitpipes are expensive to build but, once constructed, can last for a long time. Moreover, if they are well designed, they are reliable, requiring little more than monitoring and routine maintenance. However, wireless bitpipes are not inexpensive to build. And they may be more sensitive to environmental con-ditions, because both the equipment and the signals are more exposed to the elements.

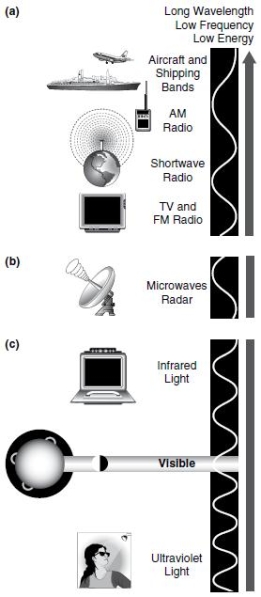

The barrier to the growth of wireless bitpipes is that the spectrum over which content must travel is expensive. The electromagnetic ( EM ) spectrum refers to the energy that travels and spreads out, a process called radiation. Radiation goes forth in waves of varying sizes - that range of sizes is the spectrum. Radiation includes light, radio (including TV and cellular mobile telephone signals), microwaves, infrared and ultraviolet light, X-rays, and gamma rays. The rate at which these waves travel is called their frequency, and each type of radiation actually includes a range of frequencies, as shown in Figure 11-2. When radio station 94.1 FM blares out its slogan - “94.1 is Number 1!” - it is encourag-ing consumers to set the tuners in their radio receiver to the 94.1 frequency, at which the station broadcasts its signals.

FIGURE 11-2 The electromagnetic spectrum . Source: U.S. Government, NASA,http://imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/docs/science/know_l1/emspectrum.html.

The EM spectrum is regulated. Devices that emit radiation are measured and the waves must fall within the claimed range. For example, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) measures and regulates the leakage of microwave ovens so that they do not cook a consumer’s liver as it cooks their pizza. Certifi-cation of most appliances is performed by Underwriters Laboratories, an inde-pendent, not-for-profit product safety testing and certification organization.

The business issue confronting companies that want to distribute content on wireless networks is simply that it can cost a great deal. Radio waves have been regulated by the government since 1904. Early radio was competitive. Stations increased their signals and jammed the signals of other stations to win the commercial battle for listeners. As a result, the Radio Act passed by Congress in 1927 declared that radio waves are public property and the government would license the spectrum, essentially rationing the spectrum. In 1993, Congress authorized the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to use competitive bid auctions to give out licenses of EM frequencies. It was a departure from a previous policy that allowed access to the public airwaves free of charge, as long as the broadcasts served a broadly defined public interest.

The auctioning of the spectrum brings in billions of dollars. For example, the 2005 auction brought in $13.7 billion to the government.17 The auction - also known as Auction 66 - raised $13.7 billion dollars for the government. But such price tags also inhibit the growth of wireless services and makes them more expensive to consumers. This condition holds true whether it is the spec-trum used by DirecTV or mobile telephones. Television and radio stations are an exception because their spectrum allocations occurred before 1993, and they continued to be honored. However, television broadcasters have been forced to move to digital transmission to reduce the size of their spectrum allocation, and the large swath of the spectrum they formerly occupied with analog signals will go to auction. (Some will go to local emergency use and other public uses.) There are several advantages to wireless delivery systems:

- They are faster to build.

- They are cheaper to build.

- Maintenance, management, and operational costs are lower.

- They are easier to expand as demand increases.

One-Way Wireless Systems: Satellites

Satellite signals, though they can be bidirectional and allow traffic to be beamed up to the satellite as well as down from it, require a great deal of energy to push them far into space. There is also some latency, as anyone changing channels on a satellite TV system can verify. These aspects make it difficult for satellite operators to offer two-way services, such as Internet access and routine telephone service. News operations often give satellite phones (satphones) to correspondents who are reporting from remote locations. They use them to file audio and low-resolution video reports, as are sometimes seen from Afghanistan.

There are three types of satellites - the highest GEOs, geosynchronous earth orbit satellites, stationed permanently in one place at 22,300 miles above the earth; MEOs, middle earth orbit satellites, positioned between 6,000 and 20,000 miles above the earth; and LEOs, low earth orbit satellites, within 1,000 miles of the earth’s surface. Satellite television programming services such as DirecTV send their signals over LEOs and low-orbiting MEOs.

Managers find satellite delivery of content over satellites very cost-effective if the content is going to many destinations. However, delivery to a single desti-nation is much more cost-effective over a wired system, because satellite deliver costs the same no matter how many earth stations receive the signal. Sending content to a handful of destinations is a calculation exercise that requires pre-cise knowledge of rates and delivery parameters.

LMDS ( Local Multipoint Distribution Service ) and MMDS ( Multichannel Mul-tipoint Distribution Service ) are sometimes called wireless cable.18 LMDS is a one-way network that delivers video content to consumers. Both LMDS and MMDS systems have fixed base stations and consumer equipment that transmit and receive signals. A network interface unit ( NIU ) connects the equipment to the network. LMDS is more powerful and complex than MMDS, but it is also far more expensive. LMDS may be useful for large companies or multiresidential complexes, particularly where wired cable services do not exist. One problem with LMDS transmission is rain fade , which occurs when raindrops adversely affect the ability of the system to transmit clear signals.

The lower cost and relative simplicity of MMDS make it more viable for distri-bution of content to and from consumers. It is also less vulnerable to rain fade. However, MMDS bandwidth is less than LMDS, so this type of system also has its downside. MMDS systems were deployed in many markets in Africa, the Middle East, Eastern Europe, the Caribbean, and Peru and Chile in South America because they were less expensive and faster to build than were cable systems in the early days of multi-channel delivery. MMDS is not used much in the United States or Europe, because these territories already have robust multichannel networks in place.

Another way to deliver content wirelessly, even video, is over mobile phones and other portable devices. Cellular carriers provide a service called 3G mobilebroadband. 3G came into existence in 2000 with the 3G designation from the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), which is authorized to set such standards. Cellular carriers have continuously added greater bandwidth to their networks. Before 3G, there was 0G in the 1980s, 1G later in the decade, and 2G (AMPS) in the mid-1990s.

There are several specific flavors of 3G technologies, but they all deliver the same bandwidth: peak data rates up to 2 megabits per second for stationary devices and between 144 and 384 kilobits per second for devices on the go.19 As of mid-2009, there is no ITU designation of 4G. The iPhone, Sprint’s broad-band cards, and Verizon’s mobile broadband service all meet 3G standards. Sprint is trialing a faster mobile service for what they market as a 4G service in Baltimore, although the ITU has not yet set the requirements for the 4G designation.

At the same time, the broadcasters are looking at another technology for mobile television as part of the Digital Television set of standards, to be set by the Advanced Television Standards Committee. The broadcasters will integrate the mobile signals into their over-the-air digital TV signal. Six stations will pilot test this new protocol in Washington, D.C., Boston, Dallas, Los Angeles, New York, and San Francisco.20 Mobile DTV will assign 3.7 megabits per second to the transmission, which will display an excellent picture on mobile devices. The system uses MPEG-4 compression, which is the same algorithm used by QuickTime for sending video over the Internet.

CONTENT MANAGEMENT: TRANSCODING CONTENT INTO DIFFERENT FORMATS FOR DISTRIBUTION

Today, every content provider must deal with the issue of multiple distribution formats. For example, a previous chapter on marketing discussed “window-ing,” the practice of the sequential the release of motion pictures in different venues, in an order from the highest to the lowest return of revenue.21 The release windows include pay-per-view and on-demand, home video (videocas-sette and DVD), premium cable, hospitality (airlines and hotels), network TV, and local TV syndicators (local TV stations and basic cable).

These multiple channels for bringing a property to consumers require mul-tiple formats. On-demand, DVD, and hospitality versions all use digital for-mats, while many of the television versions are analog. The digital formats may have subtle but real differences in the way they are formatted as well. The process of re-formatting one digital format into another is called transcoding. The need for transcoding continues to increase. Even a decade ago, LucasFilm transcoded its motion pictures into 26 different formats,22 even before the growing adoption of mobile video and high-bandwidth game consoles.

In order to accommodate the ever-growing list of distribution formats, busi-ness units responsible for disseminating content have adopted some form of content management. The earlier chapter on content discussed media asset management systems, which ingest, store, and retrieve the material that goes into the assembly of content. Content management systems ( CMS ) deal with the other end of the process - transcoding the finished content into a distribution that reaches the end customer.

CMS is a key to efficient delivery to media consumers. According to Fred Meyers, principal engineer at George Lucas’s postproduction facility, Industrial Light & Magic:

we see projects that are to be released at digital cinema and as 35 mm projected film. right now, you transfer to the d-cin master and cut the negative for the film master. we’re looking to build a system that would master for both simultaneously so we would avoid having totally separate output systems, each with its own costs. Basically, we have to make masters for each release media - film, d-cinema, video formats including standard definition broadcast and VHs, high definition broad-cast, satellite, and dVd, and web delivery. we’re looking at moving this whole process to create a single mastering system for output for all release media.23

Mass Customization and Personalization

When a content provider uses a CMS, it opens up a new world of distribution. Suddenly, it is possible to put together the benefits of mass media distribution - reaching millions of people - with the advantages of tailoring material to sat-isfy audience segments and even individuals. Indeed, if the content is stored as modular elements, a sort of on-the-fly editing can take place. There are two methods of tailoring content to create different versions for different audi-ences: mass customization and personalization.24

Personalization is adapting or sequencing solutions to fit individual differ-ences, expectations, and needs. In contrast, mass customization is adapting to fit common characteristics identified for groups. Thus, when content marketers identify audience segments, mass customization allows them to deliver a ver-sion that fits some desired characteristic of that segment. For example, a con-tent item could be versioned for different age groups, so that young children get material that is shorter and simpler. Or suppose there is a database of snippets of material on a company’s complex technological product. Individual con-sumers could check off the parts of the overall content they need and the CMSwould create a table of contents and assemble the required pieces. Students might only want (and pay for) the required chapters from a text. Newspaper subscribers may only want stories on real estate and sports, or entertainment, food, and front page headlines.

Mass customization is actually the first step in building a relationship with individual consumers. It may not always be practical or cost-effective to sup-port one customer at a time or to build in total personalization capabilities specific to one person. It may be preferable to start with a mass customized solution that identifies a few common critical success attributes that are key in satisfying the needs or wants of a particular group - well-defined objectives, analysis, and a personalization framework can guide these decisions.

Recognizing key aggregate characteristics organized by a personalization frame-work makes the individual personalization process easier to implement later with consistent, measurable results. A well-tested framework, based on sound scientific and design foundations, can help identify the capabilities, resources, and content issues that are relevant, useful, and attractive to the targeted group of consumers. Using measurement criteria implemented over iterative cycles of improvement, solutions can become increasingly personalized over time. A well-tested frame-work also helps designers tailor products and services to satisfy the wide variety of needs and gratifications for information and entertainment content.

The greatest benefit of mass customization done well is technology’s ability to make complex messaging easier by alternatively presenting content for a particular media consumer - delivering what the customer wants in the appro-priate manner and at the appropriate time. This kind of customization can apply to more than merely the content - it can also apply to the interface the customer uses. A good example of personalization is the iGoogle page ( http://www.igoogle.com), which allows user to format their own Google search page, including graphic design background, widgets for services and applications, and widget placement on the page.

The very process of customization and personalization can work to the benefit to content marketers. As consumers choose the way they want information and entertainment, providers have the opportunity to gather valuable data about each consumer that they can use in the future. Moreover, they can engage their consumers in a joint effort to shape satisfying content.

DIGITAL RIGHTS MANAGEMENT

Media companies must search continually to generate revenue, particularly in an era where digital content circulates freely on the Internet. When content was in analog form, it could not be disseminated to millions of people at the push of a button, destroying much of the potential value of that material. To protect content the company has created or acquired, many are looking at technology to help them trace their assets and extract payment for them.

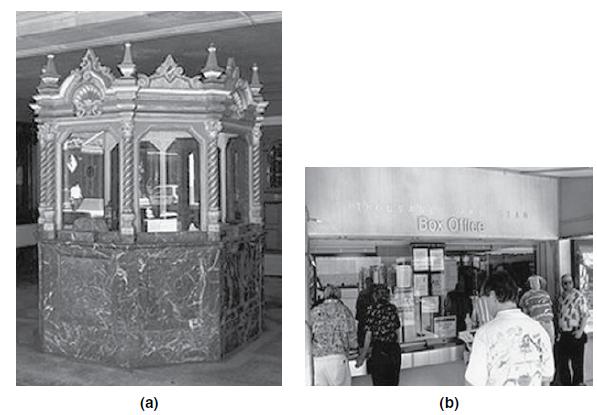

Consider the theater box office, as shown in Figure 11-3. It accomplishes many tasks at once:

- Sets an attractive “scene” for the coming experience

- Provides information about schedule

- Collects money

- Funnels customers to facility security: the ticket-taker

The theater box office has performed its job simply and effectively for nearly a century. It is the envy of digital content providers, whose content flies everywhere on the Internet, resides on millions of hard drives, forcing creators and distribu-tors to choose between losing money or suing their customers. In an electronic environment, companies can only turn to technological means to protect their revenues, an array of technologies called digital rights management ( DRM ) .25