]>

CHAPTER 13

deliver eyeballs? sell ads. deliver value? sell subscriptions.

Industry aphorism (a concise statement of an accepted truth or insight)

CONTENTS

Chapter Objectives

Introduction Business Plans and Models

Content Models

A Day in the Life of Bob Kaplitz

Marketing Models

Distribution Models

Revenue Models

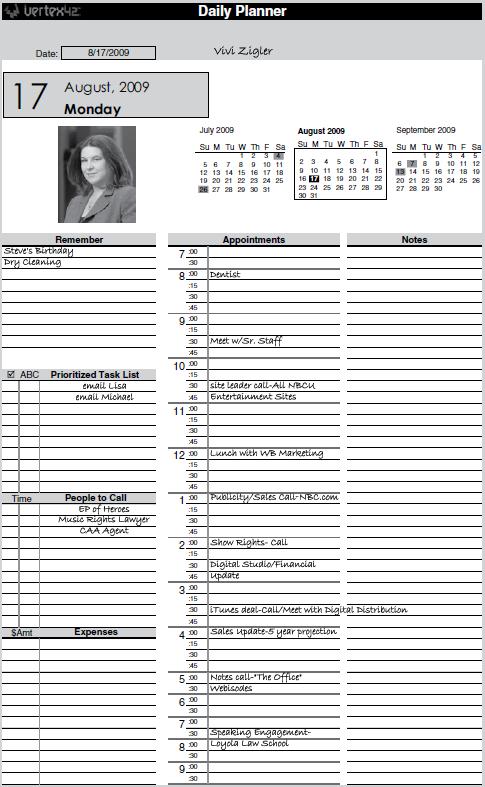

A Day in the Life of Vivi Zigler

Summary

What’s Ahead

Case Study 13.1 Back to the Future

References

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

The objective of this chapter is to provide you with information about:

- Business plans and business models

- Content models

- Content aggregation models

- Audience aggregation models

- Audience segmentation models - Distribution models

- Windowing models

- Cross-media/platform models

- Walled garden models - Marketing models

- Integrated marketing communications revisited: Spiral marketing

- Viral marketing

- Affinity models

- Data aggregation and mining

- Longitudinal cohort marketing - Revenue models

- Transactional pay per

- Licensing fees

- Flat service fee

- Subscription

- Bundling and tiering

- Access fees

- Network utilization fees

- Usage fees

- Ad-supported

- Data sales

- Content models

INTRODUCTION: BUSINESS PLANS AND MODELS

For a company to be successful, it needs to raise money, either by borrow-ing it or attracting investors. Both of these funding mechanisms require the organization to prepare a forward-looking business plan , one of the most basic documents for commercial enterprises. A typical business plan contains these elements:

- The specifics of the organization

- The management

- The products

- Analysis of the market and the competition

- Analysis of potential customers and consumers

- Analysis of marketing and sales opportunities

- Business model

- Financial plan and goals, including revenue and estimates of profitability

A generic business plan presents pretty much the same categories of informa-tion for any enterprise, whether it is making widgets, wagons, or wastebas-kets. However, business models reflect the unique customs and practices that define a particular industry or sector. For example, during the difficult transi-tion to digital broadcasting, an executive of a television network admitted that “Our business model right now is just staying in business through the digital transition.”

A model is a smaller, less detailed version of an original, as a model car presents some features of the original automobile it models. Similarly, a business model is a small, less detailed version of the business that shows how the planned company’s goals will be achieved if resources and processes are applied to the model. Ideally, if someone plugged in the numbers from the plan into the model, it would project the future financial position of the company. Business plans are confidential proprietary documents that managers cannot discuss, let alone reveal the actual numbers from the plan to anyone not authorized by the company to have that information. However, they can and do talk about their business models, usually referring to the operations and strategies that the company believes will lead to a profitable outcome.

This chapter examines the business models that have come to prominence as the marketplace of digital media and entertainment has unfolded in the past few years. Divided into content, distribution, marketing, and revenue models, as shown in Table 13-1, they can be combined with one another in any num-ber of ways to generate unique overall models tailored to the particulars of content, audience, product, distribution, and transactions.

CONTENT MODELS

The content is the exciting part of the media, the reason people line up around the block for tickets to motion pictures; hold TV house parties to watch a game, a popular series, a much-publicized episode, or other media event; and rush out to buy the newest game console. The content model begins with creative people developing ideas for content that they believe will appeal to a particu-lar audience. For example, the traditional broadcast network content model is called least common denominator programming. The audience is everyone, so the content is designed to appeal to the widest set of interests shared by the popu-lation as a whole and doesn’t exclude anyone. Over time, the most universal interests turn out to be sex, violence, news, and music.

Broadcast and cable television networks, radio networks, and print publications may all appeal to a wide audience, like Time magazine, broadcast, and basic cable networks. Conversely, many target specialized more narrowly defined niche audiences, such as publications for quilters and Christian-oriented cable channels and radio stations. Television and radio create material for the con-sumer audience; the print medium is divided into consumer and industry trade segments, which always reach audiences.

Online content does it all. Sites may appeal to a broad audience, such as Google, or address a micro-niche audience, like www.thepontiactransam.com, The questions surrounding just how narrow a niche should be are important, as they relate to both creating content and products. Mark Cuban, Internet pioneer and current owner of the Houston Mavericks basketball team, calls it the feature versus product problem.

Suppose that someone is interested in Porsche automobiles and they want to turn a time-and money-consuming hobby into an online business. Specifi-cally, this person collects the older 911S models. He is aware of the difficulty of getting some parts for the car: shock absorbers and carburetors. Should the site try to target Porsche enthusiasts; classic Porsche fans; 911S collectors; difficult-to-obtain parts for Porsches, classic Porsches, or the 911S; a parts exchange for classic Porsches or 911S cars; shock absorbers and carburetors for 911S cars - or incorporate all of these with different areas within a single Web site? Which choice will make a viable business, and how wide does the targeting have to be? Which choices are features of a larger overall product?

This problem permeates the development of products in many sectors of the new digital communications space. Take the set-top boxes (STBs) that are installed by cable companies. Should the STB have a hard drive in it? Should it provide input/output capabilities for web access? How much software should it offer? How many services? Should it be extensible to cable, satellite, phone, and DSL? Every selection has an implication for the final cost of the product, and media companies continue to wrestle with decisions about the scope of their businesses, product lines, and individual products and services.

Online efforts are particularly challenging in this regard because the costs to create Web sites are smaller than real-world markets - and there are fewer guidelines for decisions. However, like the print medium, plans for online con-tent usually call for deciding whether it will be targeted to a consumer or trade audience. Specialized content, even an entire Web site, is created to appeal to the selected group. Large corporate Web sites can have a public area, supple-mented by password-protected private areas devoted to vendors, suppliers, dis-tributors and resellers, institutional buyers, and employees.

When a site serves the general public or consumer, it is engaged in business-to-consumer (B2C) activity. When the site serves businesses, then the content reflects a business-to-business (B2B) orientation. Depending on whether the activity is B2C or B2B, the content on the site is apt to be quite different.

Broadly, there are four kinds of online content types: information, entertain-ment, services, and applications. It is difficult to separate one from the other, and they are often combined or part of an overall mix of content provided on a site. Nearly all sites provide information, which includes news, facts, anec-dotes, and opinions and associated text, graphic, and audiovisual (AV) ele-ments. Entertainment is such material as fictional stories, games, and music. (Information about entertainment falls somewhere in the middle!) It is partic-ularly difficult to differentiate services and applications. Services do something for people; applications let people do something.

B2C sites rely on information and entertainment, but increasingly they include applications and services - often in the form of widgets. Widgets are small pieces of software code added to a Web site. Even when there is no enter-tainment per se, developers try to present material in a pleasant and visually stimulating way.

B2B sites generally don’t put much effort into entertainment. They may not invest the material with any overtly attractive elements at all, although there is typically a token effort to make content readable and actionable. B2B efforts are skewed toward product information and sales. They are increasingly likely to offer services and applications, selling them outright or offering them on a per-use or subscription basis.

Online services are products or free offerings such as file sharing (including documents, videos, music, presentations), document and file storage, 24/7 availability, price comparisons, online ordering, customer service, gift reg-istries, live personal shopping assistant (voice or text), and legions of other helpful tasks. Applications are search engines, mapping, payment calculation, currency conversion, use of an online program to perform a task like photo or video editing, spreadsheet manipulation, and many other activities. Here again, there is some overlapping - search provides a service to the consumer but it invokes a program application in order to carry it out. On the other hand, a live personal shopping assistant calls upon a whole array of programs to provide the service.

Applications have led to a new class of online content providers called ASPs , or application service providers. These purveyors offer their customers the ability to use software to accomplish their objectives. An ASP can provide anything from quick lookup of stock market ticker symbols to extended sessions using sophisticated enterprise resource programs (ERP) or digital video editing. The ASP market is predicted to grow substantially to a multibillion-dollar market in the next few years, although estimates vary widely because the online busi-ness of providing applications is so new.

Whether they appeal to consumers or businesses, there are three broad cat-egories of content models: content aggregation, audience aggregation, and audience segmentation models, as shown in Table 13-2.

Content Aggregation Models

Probably every digital content provider considers several of these models when they make their plans. They can combine them easily. A company that selects the consumer experience may also decide that the interface is the most impor-tant part of the process and that the landing page is the most important part of the interface, and they may also decide to syndicate their content or to add such material to their site. What content aggregation models have in common, as shown in Table 13-3, is that they call for a focus on the content first. The audience will select itself.

Consumer Experience Model

This model holds that the content - including how it is presented, purchased, navigated, and accessed - all taken together must provide the consumer a unique and pleasant experience, not just information, data, or service. The crux of this idea is that just as goods and services are products, so are entire experiences, and they are distinct from traditional product categories. In this view, the industrial economy was replaced by the service economy, which is now being moved over by the experience economy.1 Joseph Pine II and James H. Gilmore say:

Make no mistake: information isn’t the foundation of the new economy. Information is not an economic offering. as John Perry Barlow likes to say, information wants to be free. only when companies package it in a form customers will buy - informational goods, information services or informing experiences - do they create economic value.2

Shapers of media and entertainment utilizing this approach will want to ensure that the customer will not be confused, angered, frustrated, or otherwise affected negatively by the entire process of finding, retrieving, viewing or play-ing, sampling, ordering, buying, and ultimately using the product or site. It is easy to think that designing a positive experience can be taken for granted, but research shows that more than half of people who have started a sales transac-tion on the Internet do not complete it.3 Because it takes many clicks to get through the process, such a result is not surprising. The high cost of usability and focus group research means that only the largest sites can afford detailed usability studies, but the content provider that hopes to offer an excellent user experience will absolutely require them.

In the nonprofit world, a site visitor who is highly satisfied is more willing to donate, volunteer, use the site, return to it, recommend it, recommend the organization, and leave with a favorable impression of the organization, as shown in Figure 13-1.

iGoogle provides a good example of how concern about the user’s experience has been translated into site design, because the design has been given over to the consumer. The user has many choices of design, services and applica-tions, position of widgets on the page, and widgets linking to other pages (GoogleTalk, GoogleMaps, Facebook, and many others).

Bundling and Buckets

Bundling means putting many different kinds of content together. The content can come from different sources and reflect many different types. In the cable, satellite, and PC software industries, consumers usually pay a single price for the bundled content. Online content is usually free. But large Web sites realize that in order to build traffic, they need to appeal to many people. One way they do it is by placing buckets on a page - an empty space where dynamically provided material will appear. The bucket may be filled by a news feed, Twit-ter or Facebook feed, or some other third-party-developed content. It may be produced or commissioned by the site, licensed from copyright holders, or dis-played through affiliate or affinity agreements with other Web site operators. Typically it is content that either has inherent usefulness or material people can sift through to meet their precise individual needs.

Interface Control Model

According to this model, what is really important is the consumer interface: control the interface, control the access to the content. If the content provider offers many products, users will have a difficult time finding what they want at all without a well-designed interface. This model recognizes that the interface is also content, a very specialized kind of content that engages the consumer throughout the session on a Web site, a television or music programming service, or even a list of published works, such as Amazon.com.

Control of the interface gives the ability to manipulate the customer’s experi-ence in a number of ways. The interface sets the context for the content; it establishes a thematic design, structures the choices a viewer can make, and provides mechanisms for navigation. It defines the numbers and types of choices customers can make and the procedures they must follow in order to execute them. The interface can add the element of consistency.

Powerful business incentives lead companies to provide the user interface. Beyond letting people find content, it also allows operators to present new sales opportunities. More profitable content can be featured over less profit-able content. Moreover, the interface owner has the opportunity to own a piece of the revenue, as it is the vehicle through which the consumer orders products, or gets to the order taker. Finally, it may also give access to log files of con-sumer behavior, data that enables marketers to target consumers better, and consumer contact information.

“Navigation provided by the interface is everything,” said Ken Papagan, SVP of the worldwide digital media solutions practice at iXL. “The name of the game is the race for the last interface. Every player, whether they are Google, TiVo, a cable or satellite company, a broadcast network, is looking to be that last inter-face so they can control the direct relationship with the consumer.”4

The increasing complexity of communication devices poses problems for many consumers.5 An interface that provides navigation is essential for customers on just about every device, from the television to the iPod or mobile phone. From the time they turn it on and get the “splash” or welcome screen, throughout the session, they will want to know where they are, where they are going next, and where else they could be. And it’s even more important for TV viewers that have skill levels stretching from Nancy the Netsurfer to Grandma, the Regis Philbin fan.6

Mobile telephone operators provide good examples of this strategy. They now offer an enormous range of content and services including voice messages, email, business news, local living, mobile entertainment, shopping, games, financial information, and Internet access as a premium service. The operator controls every aspect of the interface - the look and feel, all the programs, con-tent, application, products, and services that are available, and all the processes subscribers carry out when they are using the service.

From a business standpoint, this means that the operator stands to make money at every turn. They can charge content providers for reaching custom-ers, and charge customers for accessing content and services. The company also commands a percentage of any transactions.

Screen Real Estate Model

This is a variation of the interface model. Many of the advantages conferred upon the company that controls the interface also applies to the control of screen real estate. This model assumes that of the entire interface, the two most valuable parts are:

- The welcome or landing screen (also called the splash screen ), the first screen that users encounter when they turn on their devices. In some interfaces, the landing page may be called the home page ; customers return to it over and over again throughout a viewing session.

- The data glove , the top (banner or marquee), bottom, and right-hand or left-hand side of the screen, as separate from the main part of the screen or the center of a web page, where the consumer-requested information is displayed.

The inventor of the concept of controlling consumer access to content and providers access to consumers was Bill Gates, whose masterful desktop real estate strategy was an important arrow in the Microsoft quiver until the advent of the Internet browser: first Netscape, now Internet Explorer and Firefox. Before the Internet, personal computers booted up into Windows and that was that. When the enormity of the threat to the Windows desktop hegemony posed by the Netscape Internet browser became clear, Microsoft moved deci-sively to package its own Internet Explorer browser with its Windows operat-ing system. However, the browser does not allow for the execution of a screen real estate strategy, because it takes little expertise to set up a personalized home page.

An interesting contemporary execution of a screen real estate strategy on the Web is Google’s iGoogle customized page, which gives control of almost all the spage to the user, helping to ensure that the user will sign into Google and access their designed page. At the same time, Google still controls the all-important data glove that surrounds the user’s elements.

Enhanced TV Model

The meaning of enhanced TV keeps changing. The basic idea of this model is to allow information from multiple screens to be co-presented on the large display in the home, usually the television screen. Originally, it allowed owners of linear programming, such as TV shows and movies, to make their content interactive. Hot spots , clickable areas on the video, allowed viewers to receive more content, usually text, on the screen, over the video. When clicked on, the hot spot might even open a Web site window and overlay it on the moving video.

More recently, Time Warner Cable in New York used it as a kind of built-in DVR, offering such capabilities as:7

Start Over: Restart program from the beginning

Quick Clips: Watch a video clip from a show

Look Back: Replay a missed show

PhotoshowTV: Subscribe to a service that puts a photo slideshow on the TV screen

User-Created Model

Think YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Epinions, Blogger, Ning, del.icio.us, and Digg - all user-created content. Then there are the sites that rely heavily on it, like Yelp and every Internet e-tail site that solicits consumer and user ratings.

Early in the development of the graphically rich Internet, about 1998, it became obvious that populating a Web site with content is demanding and expensive. At the same time, many people want to express themselves and create material they can share with others. Sites that post material for the public often feature it as the majority of their content. Content providers following this model find that it does require some administration. The procedures for posting mate-rial must be clear. Similarly, rules must be prominently displayed and strongly enforced. Sites for the general public most often guard against pornography and other offensive graphics and language.

User-created material makes the most sense for the Internet. This type of con-tent requires a great deal more tweaking in digital television venues such as over-the-air TV, cable TV, and even broadband TV. For example, home video compilation shows like America’s Funniest Videos entail a staff to search out videos, gather them, order them into a rundown, and edit them. The produc-ers then contract with (relatively) expensive talent to host the show, doing the on -camera pieces that introduce the show, each video, and the closing. The studio audience gives the program the added energy of live viewers.

Formats based on user-created content have not moved to radio or maga-zines, but music, podcasts, slideshows, and photos are everywhere - all on the gazillion-channel Internet.

Naturally, user-created content is the primary offering of personal Web sites, and many thrilled content creators - artists, musicians, writers, filmmakers - have enthusiastically pitched the Internet as the ultimate way for creative people to reach an audience. But there is some disagreement with this position. The counterargument is that there is such an avalanche of material on the Internet that no one person can be seen or heard. In fact, say these people, the ubiqui-tous Internet gives all the advantage to those with an existing brand name - stars and hit labels - because only a recognized and recognizable brand can break through the clutter.

Some observers believe that there may never be any real hits on the Net, in the way that other media, such as motion pictures, television, and music, all have blockbusters. In this view, the ability of people to match their wants and needs with precision undercuts the ability to aggregate large numbers of consumers for any length of time. The only way a site can build an audience is to aggregate enough content to attract a lot of individuals, a strategy that often involves including user-created content.

Syndication and Licensing

Syndication and licensing are simultaneously a content aggregation strat-egy, a way to build a bigger audience, and a revenue strategy to bring in money. Syndication and licensing are old hat in motion picture, televi-sion, radio, and newspapers. But they are still new and evolving on the Internet.

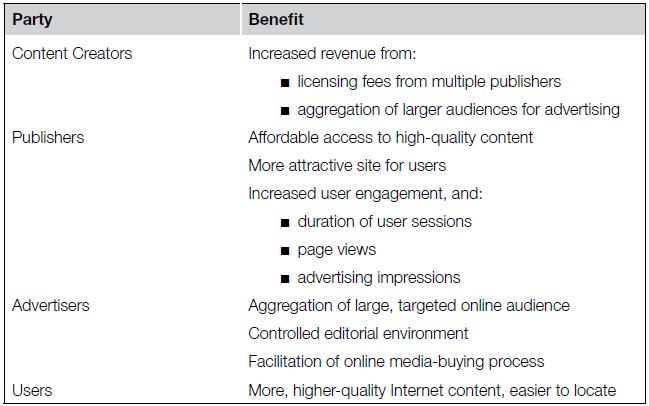

Web site operators and owners can populate a site with content that is geared toward their particular audience, without bearing the expense of an edito-rial staff. There are benefits for other Internet players as well, as shown in Figure 13-2.

There are two major types of syndicated distribution on the Internet, although the field is still evolving and could change. Full content syndication means that through some contractual arrangement, content is circulated to a Web site or a link is sent that allows the content to remain on the site where it is stored, but is shown in the window of the site where the link is accessed. Control of the content’s distribution is generally retained by the original content creator or owner, although there may be some modification by the site displaying the content.

RSS, or Really Simple Syndication, is a system whereby the content originator allows users to receive the content automatically. From the point of view of the content owner, RSS is a distribution model, but from the perspective of the user, it is a way of aggregating content. The user installs an RSS reader on the local computer, allowing the person to choose material and construct their own individually tailored “channel” of information. Control of content distri-bution passes to the receiver in this model.

Audience Aggregation Models

The content models we just looked at start with aggregating content and then look for audiences for it. Others models reverse that process and begin with strategies for aggregating a particular audience or set of audiences, then assem-bling content that will appeal to them. Broadcast television is the most success-ful industry ever to use an audience aggregation model, beside which all other media pale. Cable TV, radio, and print have a few broadly popular properties, but many more of their products serve niche audiences.

Horizontal Portals and Destinations

The early success of portals like America Online in capturing tremendous traf-fic on the Internet set off a race by media and entertainment giants to get their own branded portal. In rapid order, Disney, NBC, and Warner Bros. bought and built their way to mega-portal status. A portal is a way station; a destination is a place to spend time, a “sticky” site where people stick around for awhile. The

Audience Aggregation Models (Broad Audience)

Focus on an audience and create or acquire content that appeals to a broadly defined audience or to more than one targeted audience

| Horizontal portals and destinations | Put together a wide range of material to attract a similarly wide range of people |

| Free content or service | Give away attractive, high-value content to draw an audience to it |

most important feature of a portal is usually a search engine, which captures as many listings of Web site content and services as possible and displays the returns in an efficient and readable manner. A destination site requires many more services and bits of content than a site designed only to offer search engine services.

The distinction between portals and destinations is becoming more blurred as search engine-based sites expand to include many more services and applications. Of the following top 20 sites on the Web from the Alexa traf-fic ranking, eight of them are Internet search engine-based portals, six are communication-related portals (Facebook, Twitter, QQ.com, etc.), two are user-created destination blog sites (Blogger and WordPress), and the rest are infor-mational sites of widespread interest (YouTube, Wikipedia, and Microsoft). One offers a service (RapidShare).

Yahoo!

YouTube

Windows

Live

Wikipedia

Blogger.com

Microsoft Network (MSN)

Baidu.com (Chinese)

Yahoo! (Japan)

MySpace Google (India) Twitter

Google.de (Germany)

QQ.COM (Korea)

Microsoft Corporation

RapidShare

WordPress.com

Google.fr (France)

Google.uk (UK)

What does it take to be a portal? The best way to answer this question is to look at Google. The search site http://www.google.com is simple - use the search engine. However, on iGoogle, users can create their own portal, using thou-sands of themes and backgrounds, hundreds of individual applications called widgets or (on Google) gadgets , such as a to-do list, calendar, local map, local weather, a wide variety of news feeds, IM and Facebook sign-in and connec-tion, and many others.

The difficulties of establishing a horizontal portal today should not be under-estimated. The Walt Disney Company, no stranger to aggregating an audience, acquired search engine Infoseek and put it together with the company’s other Internet entities to launch Go.com. In 1998, Go.com took in $323 million and lost $991 million for the year; in 1999, the site took in $348 million and went $1.06 billion into the red. Internet traffic measurement service Alexa ranks http://disney.go.com at number 96 in the United States and 303 in the world. Although this traffic is good, it is not sterling. The Alexa service describes the loading time of the site as “very slow,” slower than 86 percent of rated Internet sites.8

Free Service Models

Building an audience by offering free service has a long history in broadcasting. That model has transferred to the Internet and become a popular strategy for many Web sites. Like radio and television, much “free” content is supported by advertising. Often called a “freemium” model, marketers offer some services for free, and pitch the consumer to upgrade to the premium tier for additional features or services.

- Internet access, web domains, and hosting

- Blog and social media page

- File space and file sharing

- Video, audio, and photo sharing

- Recommendations (Epinions, Digg, etc.)

Audience Segmentation Models

The Internet is the inverse of broadcast television - it has an unmatched ability to reach specialized audiences, and relatively low cash outlays for production and distribution make it cost-effective to do so. Interested in aviation history, aviary management, or.avi file conversion? There’s bound to be a treasure of information on the Internet, just waiting for you to discover it. The following models all exploit this ability of the Internet to attract people who are united through some common experience or interest.

Audience Segmentation Models (Niche Audience)

Focus on an audience and create or acquire content that appeals to a specifically targeted audience, often quite narrow.

| Vertical portal and destination model | Target consumers that have a specific interest and create content to appeal to them |

| Internet community models | Put together content that appeals to a group of people who already come together to interact with one another |

Vertical Portal and Destination Model

A horizontal portal aggregates content to appeal to as many people as pos-sible. A vertical portal defines a segment of the potential audience and then assembles content that relates to this segment. So how wide is a horizontal portal and when does it become a vertical portal? Or conversely, how narrow is a vertical portal and when does it become a horizontal portal? The basic difference is that horizontal portals begin with assembling content, and a vertical portal begins with a segment or a content type. Verticals may be very wide. iVillage ( http://www.ivillage.com) is designed for women; ThirdAge ( http://www.thirdage.com ) is a site for middle-aged boomers. Bolt.com (http:// www.bolt.com) targets older adolescents and twenty-somethings, and Webkinz ( http://www.webkinz.com) is for kids.

There are also portals that are very narrow, serving vertical interests like Bikersites.com ( http://www.bikersites.com) and Adobe’s file conversion info Web site ( http://file-conversion.web-design-tools.com). Here’s narrow for you: bird-lovers who want to know how to build an aviary for budgerigars can always turn to http://www.budgerigars.co.uk/manage/.

Internet Community Models

In some ways, making community a centerpiece of a Web site or digital service is often a particular case of user-generated content. However, all user-generated content is not based on a community, which involves creating Internet ser-vices that allow members of the group to participate in communication with one another. The means of communication may be an asynchronous message board or email discussion list, where participants post their comments, and then sign on later to read responses and post again. Or it might be real-time chat that lets participants conduct text-based or audio chats. Adopting the Internet community model doesn’t mean there is no other content. Usually operators put additional material believed to be of interest to the members of the group on the site. Information, services and applications, and e-commerce interactives are quite commonly found on community sites.

Communities can form around any sort of interest or concern, and there are thousands - perhaps hundreds of thousands - of them on the Internet. Poli-tics is a powerful community builder. On the Democratic side, http://www.dailykos.com has more than 215,000 registered users and receives 2.5 million unique visitors every month. The Republican equivalent, http://www.redstate.com , does not publish the number of the site’s registered users, but says it has tens of thousands of readers. http://www.proteacher.net is a community for K-12 teachers.

Some entertainment sites, such as the online game World of Warcraft (http:// www.worldofwarcraft.com), create a site-related community on their main Web site, like http://www.worldofwarcraft.com/community/.

The communication between people on the site, most of whom do not know each other in their “real life”, may make up all or a large part of the content. However, bound by some commonality of interest, location, or cir-cumstance, they may seek the same content. Content sellers may promote offerings they think will appeal to the community through membership or ads placed on the community site. Figure 13-3 shows how community-driven content brings people into an orbit of shared experience that can influence later behavior.

A DAY IN THE LIFE OF BOB KAPLITZ

Bob Kaplitz, Principal and Senior Station Strategist for AR&D and Author of Creating Execution Superstars with Budgets Cut to the Bone

Bob Kaplitz is a principal and Senior Station Strategist for AR&D. He’s a thought leader and influencer in an industry that requires unprecedented transformation and operational change to sustain long-term value. For close to 30 years, he’s built winning strategies for clients, helping them become high-performance leaders in their local markets. Using mar-ket research from the company’s analysts, he makes recom-mendations to clients for product development, marketing, and branding.

When he studied psychology as an undergraduate, he focused on learning and motivation. He assisted in experi-ments aimed at understanding how people learn and how to accelerate learning.

At Syracuse University’s Newhouse School of Public Communications, he studied advertising and journalism for his master’s degree. On a university-sponsored trip to Washington, DC, to visit news bureaus, he had the fortune to meet Dan Rather, who was CBS News’s White House corre-spondent. Rather took time to show Bob around the cramped “press room.” He didn’t expect it to be glamorous, but it was no larger than a small cubicle.

After graduating, he became a reporter at a Greensboro, North Carolina, station where he also anchored the station’s Sunday night news. He shot many of his own stories. Bob also taught broadcast journalism and TV production at the University of North Carolina several evenings a week.

When Dan Rather spoke at a university event, Bob reconnected. Rather said, “Send up a flare when you’re in New York,” and the two met for dinner in New York several months later. “Can I watch you put your show together?” Bob asked. He said sure.

Bob recalls that Rather, who was anchoring the weekend news for CBS, was driven to success. “He made anchoring a small part of his job. He was always in motion. Even though he had a producer and writers, he was actively involved in the pro-gram, calling correspondents about their story. And even after the show, he took the time to thank them for their reports, sev-eral of which were ’via satellite,’ which was a big deal then.”

After 5 years in Greensboro, everything changed. He revealed corruption in an area police department, and the police chief sued him for $8 million, pressuring his station to back off. The station supported Bob who continued his reports, the police chief resigned, and the Radio TV News Directors named Bob “Best TV Investigative Reporter in the United States and Canada.”

A Miami TV station hired Bob as a reporter to cover the crime beat - from Miami vice to organized crime. Many of his stories ran on the CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite and on CBS Radio.

After serving as an executive producer at a North Carolina TV station and as an investigative reporter in Dallas, Bob joined a relatively new TV news consulting firm, now known as AR&D, spending the first few months learning the ropes behind the scenes and then was allowed to conduct workshops at TV stations. His presentations were based on what viewers liked and disliked about TV news. The company would only trust him with smaller markets like Terre Haute, Indiana. Then he “graduated” to consult in major markets like Atlanta, Detroit, Cleveland, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. He created innova-tive workshops that engaged participants by involving them.

He also conducted several consulting “tours” to Australia and New Zealand, helping them to build their brands of jour-nalism and ratings.

While with AR&D, he volunteered as Vice President for New Media for the Dallas-Ft. Worth chapter of the American Marketing Association, pioneering videos previewing the presentations of upcoming speakers. The videos posted on the organization’s site drove up attendance. It was a valuable learning experience to interview many of the world’s global marketing leaders.

Bob also occasionally taught international advertising, marketing, and digital marketing at the University of Dallas Graduate School of Management. It was an opportunity to teach and also learn from MBA students who came to Dallas from many parts of the world.

In 2009, Bob began playing a major role in the compa-ny’s reengineering initiatives, which included training the new breed of multimedia journalists. This included reporters who need to learn how to shoot and photographers learning reporting. His blog, http://www.kaplitzblog.com, registered more than 100,000 hits over a periods of only a few months, with users from as far as China and India.

A Typical Day

When I’m in Dallas, I usually wake up about 6:30 a.m., check-ing email from my home office. I try to complete projects from the previous days because many clients have a “I want it now” approach, which I fully appreciate. Plus I don’t want my to-do list to get too long.

I critique newscasts or newscast elements after viewing them on line. As brands of journalism are so crucial to ratings success, I focus on how successfully the shows deliver on their brand’s promise. For example, if a station claims to be Watching Out for You or On Your Side, does it deliver? Because it’s difficult for many journalists to understand the impor-tance of a brand, I offer specific examples how they could have done better. The fun part is celebrating successes - whether big ones or small steps.

Anchors, reporters, photographers, producers, and news managers crave feedback, so I share a longer list in my What Worked section than in How to Raise the Bar? We all can only focus on a few new challenges to do them well.

Typical incoming emails and phone calls:

- News director needs help in explaining how an anchor can implement a franchise called “Fact Finder,” which goes the extra step to reveal facts - like a crime trend in a neighborhood thought to be safe. In cases like this, it’s often a matter of explaining the value of the concept to the anchor, reviewing actual examples and then dis-cussing the steps necessary to implement successfully.

- Promotion director is disappointed with sweeps plans. Nothing strong to promote. I promised to set up a conference call with the news director to help. I usually review a Sweeps Planning Checklist, which includes questions like “Does the story interest the vast major-ity of viewers based on our research?” and “How will viewers appreciate the fact they can only get this new information on our station?”

- General manager asks for my help interviewing by phone a couple of news director candidates. As many candidates are practiced interviewers, knowing what to say, the goal is to learn how the applicant will handle actual challenges he or she would face at the station.

- A news director calls with a reporter in her office, asking me to walk her through the steps necessary to ask tough questions. The reporter doesn’t want to upset the mayor, losing him as a source. But when I ask the reporter how many exclusives she turned thanks to using the mayor as a source, the answer is none. Even so, I suggest ways to state that the questions and complaints are from viewers, so the reporter is giving the mayor a chance to respond.

I’ll also continue creating Learning Videos on my blog, http://www.kaplitzblog, which are primarily aimed at the new breed of multimedia journalists. As it’s easier to learn by example, the blog shows examples often with my comments at the bottom of the screen.

I interact with a range of people including the heads of groups of TV stations, general managers, news directors, pro-motion directors, promotion producers, reporters, photogra-phers, multimedia journalists.

Inside AR&D, I collaborate with a research analyst for project definition calls with clients - deciding what ques-tions they want answered. We also work closely in crafting recommendations once we get the data back.

Because many news people believe viewers think like they do, the scientific surveys we do provide a reality check from our customers - viewers. For example, some reporters used to thrive on going live when nothing was going on. You probably have seen reporters standing in front of buildings, for example. Viewers find that a waste of time, seeing as “filler” when there’s no “real news.” Viewers find reporters reporting from the newsroom even worse. “Why don’t they get out to the scene where the story is?” viewers ask.

As part of AR&D’s transformation of TV stations, multi-media journalists will go directly from their homes to stories, posting stories to the station’s Web site and feeding com-pleted stories to the station for newscasts. No sitting around in the newsroom reporting away from the scene.

People issues are the most challenging - especially when they’re failing but don’t recognize it or don’t want help. No matter how daunting the challenge, individuals who recog-nize they have something to learn can learn. We take it step by step, based on best practices applied to the specifics of their challenge. But those who resist can’t improve because they choose not to.

Often they have good reason. For example, they got bad advice. Or they were set up to fail because their manager didn’t believe in them. Whatever the reason, we try to show them they’re not performing the way they should. Then we point out how the manager and I can take them step by step through solutions.

We all thrive on ratings improvements, but the deeper highlight and sense of accomplishment come from seeing the success of people. Sometimes it’s a first-time news direc-tor who had difficulty at first gaining the respect of her staff - and finally does by following our plan. Other times it can be a promotion producer who admits he doesn’t understand how to create an image campaign and then follows best prac-tices and our strategy to develop one. Several clients who used to be at smaller markets have risen in the ranks to the

networks, and it’s always rewarding to see people achieve their potential.

After I complete the projects I’m working on and respond to calls and emails, I feel a great sense of accomplishment. Often that happens at 6:00 p.m., but sometimes 10:00 p.m., when I travel and need to respond after visiting with the client.

After normal work hours, I check email on my iPhone, responding to those questions that only take a few minutes. I like to put myself in the client’s shoes, appreciating a quick response when possible. When issues require more thought or collaboration, at least I try to acknowledge the question, promising a time frame when I’ll get back to them.

For those looking to enter the field of electronic media, I offer these three major points:

- learn as much as you can as fast as possible. When you look at your career, it shouldn’t be one year times five, for example, for five years of experience. Rather, you grow in a big way every year. Every month.

- be flexible. The “old ways” are disappearing fast. Simply put, “adapt or die” may seem threatening, but it’s true.

- be bold. Even the most successful people failed at their first attempts and then did better next time. Just make sure you’re doing the right things rather than simply what you’re used to doing, which may not benefit you or your TV station.

We have a unique point of view since we, as a company, are revolutionizing how local media produce and distribute content as they face their toughest business challenges ever. We create new innovative operating models, organizational and workflow strategies, and personnel alignment mapping for clients. The result is a stronger, more responsive organiza-tion with higher productivity levels and greater efficiencies from top to bottom and from beginning to end. To be part of that future I see, you need to get started now.

MARKETING MODELS

Marketing models (Table 13-4) explain how customers will find out about the content and the products and services and be convinced to view, access, rent, or buy them. They answer the questions: What appeals does this particular content hold for a given audience segment, and why should these people pay attention to it and consume it? How will they find out about it and how can the appeal be best communicated? The next section looks at marketing models to execute both brand strategies and media and entertainment product promo-tion and sales.

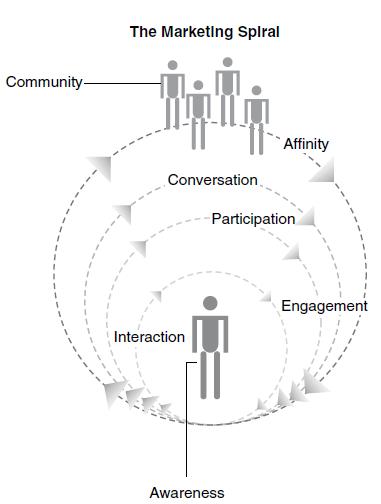

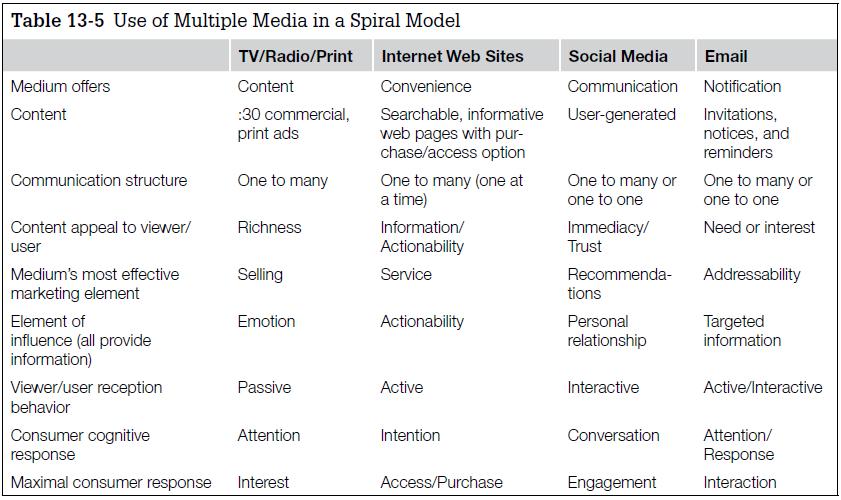

Revisiting Integrated Marketing Communications: Spiral Models

You’ve probably seen and heard all the broadcast advertisements that urge people to visit the Web site. Much of the new media advertising on traditional media is driven by the spiral model, which says that communicators can use multiple media to reach the consumers with messages about the same product but influence them in fundamentally different ways. The main idea is that each medium should be used for what it does best, as summarized in Table 13-5.

The original spiral model called for using traditional media first - TV, radio, print - because they reach the most people, and they are also best at raising interest and building an emotional connection between the brand and large

numbers of viewers.9 The mass media message should direct consumers to a Web site for several reasons:

- It is an actionable medium - people can get more information and order conveniently if they want to purchase or access content.

- A Web site can incorporate multiple service components, like price comparison, customer support, gift registries, custom ordering, online price discounts, etc.

- A Web site offers an opportunity to collect information about individual consumers.

Once the marketer has the email address, he or she then circles to another medium: email, which establishes a one-to-one relationship with the con-sumer. Email closes the loop with a thank-you, followed up by notices and reminders, always sending the person around the spiral again by directing him or her to a TV or radio broadcast or print story.

The relationship can be maintained through the use of a fourth medium - social networks, particularly if the consumer is an influencer in the particular area of interest to the content marketer. For example, if the customer orders many movies or clicks on a lot of videos, then the content seller can ask this consumer to join a panel on a wiki site , where the consumer can be engaged further in the product presentation and choices. The marketer hopes such customers will buy more, but even more important, will involve their live and virtual friends, giving the campaign a viral boost.

It is important to repeat this spiral (mass medium, Internet, email, social media) as quickly and as many times as possible. It also calls for consistency in the mar-keting message so that consumers stay engaged with the brand and recognize it across media. Also, a consistent message allows customers to draw on their own experience to reexpress it to friends in their own authentic terms. An example of consistency is the NBC three-note audio signature and the peacock colors, no matter where their content appears, making the brand immediately apparent.

The power of spiral marketing comes from the fact that if it is repeated quickly and often enough, it builds a virtuous circle. This is a set of events where one propitious event leads to another, finally returning to the starting event to begin again. An example might be the development of an innovation, which leads to investment, effective marketing, increased productivity, higher economic growth, greater consumer buying power, which create profits that are used to underwrite efforts to develop more innovations. In this case, the virtuous circle leads to a seamless blending of brand management and customer relationship management (CRM).

The problem with spiral marketing is that it is very expensive. In some cases, the cost of acquiring customers is more than a content seller can hope to recoup in any reasonable amount of time. For this reason, some marketers start with a viral campaign, executed in social media venues and build toward a mass media exposure.

Viral Models

Viral marketing means to create a campaign where users act as your market-ing agent, communicating your marketing message to their real-life and vir-tual friends. This is contagious communication, where “spreading the word” resembles how people pass colds and other viruses to each other. The genesis of the term probably came from Douglas Rushkoff’s book Media Virus , which suggested that mass media programming contained hidden messages intended to spread counterculture attitudes and ideas.10

Viral messages can take place in face-to-face conversations, via email, and on social networks, and Twitter. Content sellers find viral marketing especially useful, as media is often the subject of such exchanges, and people pass on recommendations to their friends. Marketers can design materials with viral passalong in mind, encouraging customers to forward the message to their network of acquaintances.

There are many examples of successful viral campaigns. An early example was the Blair Witch Project. Since then, Cloverfield and the Dark Knight have launched notable viral efforts. Nine Inch Nails helped launch their album Near Zero by putting viral material on USB drives left for concert-goers to take home and upload to the Internet.

Affinity Models

There are two meanings for affinity marketing. The traditional model calls for marketing to existing groups of people, such as members of associations and clubs, employees of the same company or industries, students, other social groupings. Once identified, a marketing effort typically offers special arrange-ments, programs, or discounts for people who are in the affinity group.

On the Internet, affinity model refers to partnerships between Web sites that attract consumers who seek similar content. People may share an interest in the same content, but have quite different reasons for doing so. The common interest alone may propel them to look for compatible or complementary con-tent, services, and products. To commercially exploit this relatedness, a part-nership agreement between two or more Web sites that reach similar segments establishes URL links between them. Such partnerships are most widely used by sites that sell gambling, pornography content, and some retail products.

For example, a site that features real estate might partner with lenders, and a home improvement chain store. Similarly, a guitar manufacturer could execute agreements with a site that hosts a community of music creators, a songwriter’s site, a musical instrument web store, a sheet music merchant, repair services, and so forth. It doesn’t really matter that one guitar player wants to play funkadelic and another classic flamenco.

Data Mining

Viral and spiral marketing both focus on reaching new customers. Steve Milanovich of Merrill Lynch refers to monetizing customer relations as hunting vs. gathering. Looking for new customers using a viral or spiral marketing model is hunting. Pitching existing customers for an additional purchase is gathering.

Data mining is a gathering technique for using information about customers to create targeted value propositions to them. If a marketer knows a set of facts about a past buyer, analyzing that data in detail can provide guidance for such efforts. Sometimes additional information, such as zip code characteristics and census data can be added to the mix, giving powerful additional clues about how to approach a given customer. The more interactions a seller has had with an individual, the more targeted the approach can be.

Data mining is inherently cost-effective. Snagging a new customer for a retail site can be as much as $41, while some of the most well-known sites pay con-siderably less. For example, buy.com pays $22, Amazon.com pays $12, and eBay.com pays $8 for each new customer. Online stores can expect to pay 7-8 percent of their total revenues to acquire revenues.11

Over the past decade, data mining techniques have become very sophisticated. Supported by ever faster computers and better software, marketers can now simultaneously analyze multiple data sets, such as credit card data, census data, and consumer data. The result is that individual consumers can be targeted as narrowly as “Jane Murphy, 36, of Irish extraction, attended Boston College, earns $84,000 in a middle management job at an identified publishing com-pany, owns a condo, a time-share in the Bahamas, and a Toyota Camry, views five on-demand movies per month, watches House, Runway! , and CNN , has a GlobalFit membership, donates to a political party and several nonprofit orga-nizations, and uses an expressway E-Zpass for her daily commute to work.”

Longitudinal Cohort Models

This revenue model goes particularly with audience segmentation content schemes, which offer material to a specific group of consumers. It tries to antic-ipate over time the array of wants and needs members of the group have in common, to provide content that interests and supports them, and to wrap around and embed appropriate ecommerce solutions. Mariana Danilovich, CEO and president of Digital Media Incubator, LLC, is an articulate advo-cate of this perspective. “This whole game is not about the creation of great programming. It is about serving a niche demographic. Now you can’t serve a niche demographic with a single property. You can be very creative but it’s the whole experience, designed with the entire lifestyle of the audience in mind, allowing you to fully serve the target demographic,” she advises.12

A key element in this model is that it follows the same group over time, perhaps many years. A marketer using the model must continue to profile consumers at regular intervals so that the content and ecommerce opportunities evolve with the changing customer. The Web is still so young that this aspect of cohort mar-keting is only now surfacing as people in the Gen X cohort enters their thirties. E-tailers who focused on that group must now shift their strategies from urban, fashion-conscious, entertainment-driven singles to suburban marrieds with chil-dren buying their first home and entering the substantive years of their careers.

MTV is an example of a network that decided not to follow the longitudinal cohort model. Instead, it now programs to meet the needs of a core audience of adolescents, moving away from the Gen X group that made the network popular. By contrast, the CBS broadcast network appears to have adopted the model throughout the 1990s and the 2000s, putting on programs that appeal to an older audience, which in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s made the network the ratings leader.

DISTRIBUTION MODELS

Once content is developed, a distribution model lays out how the content will get to consumers, in terms of media platforms and technologies. In times past, the product itself defined its distribution: Movies were shown in theaters and later rented from video stores; songs were played on the radio and then pur-chased in stores that stocked vinyl record stores and later CDs; TV shows were shown on TV, and so forth.

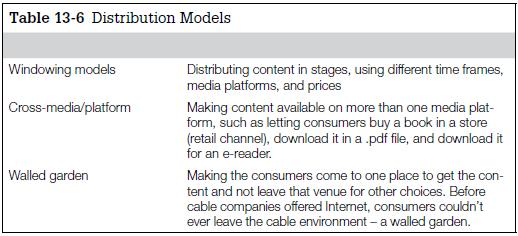

In the digital environment, it is no longer clear how a given content vehicle will reach consumers. A song is played on the radio, on an audio pay service over cable and satellite, on the Internet, or over a mobile phone. Three distri-bution models that address this new reality are currently extant: windowing, cross-media/platform, and the walled garden shown in Table 13-6.

Before considering the models themselves, there is one further wrinkle in distribution - the relationship between providers and consumers in delivering material. The two-way Internet has fostered a new characterization of distri-bution media and formats as push, pull , and opt-in , or pull-push. Push means a distribution effort that sends out content to people whether they want it or not, such as broadcast TV and radio, spam email, and direct mail. Pull means a distribution that is requested by the receiver, such as going to a Web site and downloading a file: a request-receive format.

Opt-in might be characterized as pull-push. It reflects the need for companies to avoid irritating the consumer. The client makes a request which is then ful-filled at the sender’s express choice. Examples of opt-in distribution are cable and satellite TV, requested email newsletters and other messages. In each of these cases, consumers ask to receive the content before they get it, and then keep on receiving the content until they opt-out , or request to end the service.

Windowing Models

This model is a marketing, revenue, and distribution model, depending on the context. When it is discussed as a way to reach ever less eager buyers, it is a marketing model; as a way to set ever lower prices, it is a revenue model; and as a way to plan sequential releases on different platforms, it is a distribution model. As covered in an earlier chapter, it is a marketing strategy and revenue model that originated with motion pictures and, to a limited extent, has now been adopted by some television series, networks, and programs as well.

Windowing means to release a property in stages for a specific length of time, the window. In the motion picture industry, it describes the wholesale level of film distribution. The order of the release windows is based on the revenue brought in per viewer. Domestic and international theatrical release comes first because each viewer pays for a ticket, $4.50 to $12.50. The pay-per-view window is next with a charge of $4.00 to $5.00 per household, followed by home video rental for $3.00 to $4.50 per night. After these windows follow premium cable, foreign TV, network TV, syndication packages for TV stations and basic cable channels, each window bringing in a smaller and smaller flat fee or package price.13

Revenue per viewer is not the only conceivable way to structure release windows. Strategies for reaching particular audiences or media platforms might define them. For example, one analyst proposes that film studios cre-ate an early release window via satellite HDTV channels, a first-run HDTV channel. It would feature pretheatrical releases of movies to households that have HDTV sets. Dale Cripps, who developed this idea, believes that there are about that many people who would pay $10-$20 to be the first ones to see new films.14 The income would be substantial, and it could provide valuable word-of-mouth to support the theatrical release right afterward. (Maybe this wouldn’t offer much good publicity for disappointing films!)

Digital windows include DVDs, video CDs, digital cable networks, and the Internet. Slicing and dicing of motion picture content permits the distribution of snippets, portions of text, individual scenes, and single photos. The distribu-tion of music has been disrupted by sharing over peer-to-peer networks, but it is possible that windowing could apply to many other content types. For exam-ple, songs could launch at a concert, move to pay-per-song over the Internet (with expiring rights protection), then to CD-ROM, and finally to subscription audio channels over cable and satellite.

Cross-Media/Platform Models

The cross-media/platform model means distributing content across more than one medium or to more than one type of reception device. Like windowing models, it may be cited as a marketing and revenue model as well as a distribu-tion model. Consumers differ in where they want to enjoy content, and many people use more than one device. The same person may watch a video on TV, on their mobile phone or portable DVD player, or over the Internet at different times and locations, with varied motivations. They may also combine media with the Internet, such as simultaneously watching the content while partici-pating in interactive or social activities.

The changing content consumption habits of the public mean that content providers and distributors must now reach their customers wherever they hap-pen to be, on whatever devices they choose to use. Creating material for differ-ent delivery platforms, network access speeds, formats, reception devices, and consumer characteristics is another way of saying that content must be custom-ized, tailored to address many different environments, conditions, and con-sumers. In the digital world, more and more content companies think about distribution as create once, publish everywhere.

Sun called this strategy chasing the consumer , delivering content to consumers and tracking their responses across multiple media and platforms. The target audience may be broad or narrow, but the content is tailored to the needs and desires of that group. It is created once and automated procedures convert it to needed formats for distribution across multiple media. This means that con-tent must be flexible. It must be an exciting print vehicle, a compelling televi-sion program, a sticky Internet attraction, and an e-commerce bonanza. The cost of the content is amortized from revenues derived from all sources, across the various media where it appears.

Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia, LLC, pioneered a cross-platform distribu- tion strategy, with business ventures divided into four segments: publishing, television, merchandising, and Internet/direct commerce. At the height of the company’s activities, the content creation empire included:

- A monthly magazine ( Martha Stewart Living )

- A quarterly magazine ( Martha Stewart Weddings )

- A syndicated one-hour television show ( Martha Stewart Living )

- Weekly CBS This Morning appearances and periodic CBS prime-time specials, all in partnership with divisions of CBS Television

- Half-hour program twice a day, seven days a week on Food Network cable channel, that consists primarily of food-related segments from previous Martha Stewart Living television programs

- Books written by Martha Stewart and the editors of Martha Stewart Living

- A syndicated newspaper column (askMartha)

- A national radio show (“askMartha”)

- A mail-order catalog and online merchandising business (Martha By Mail)

- An Internet Web site that features integration of television programs, radio shows, newspaper column, and magazines, as well as seven distinct chan-nels on the site, each devoted to a core content area - Home, Cooking & Entertaining, etc. Each channel offered live discussion forums, 24-hour bulletin boards where visitors post advice, queries, and replies, and weekly live question and answer hours with in-house and guest experts

- Strategic merchandising relationships with Kmart, Sherwin-Williams, Sears, Zellers, and P/Kaufmann.

Walled Garden Models

Walled garden is a term often attributed to TeleCommunications, Inc. founder John Malone. It is a closed network that keeps subscribers within a restricted area. Inside the garden, the subscriber can choose from a bouquet of services that are carefully selected, controlled, and often created and operated by the network providing company. Walled garden services do not permit unfettered access to the Internet. Cable and satellite companies operate walled gardens on the television side of their operations, but when cable companies offer broad-band network service, they market unlimited Internet access.

As media become ever more converged, walled gardens are likely to be more difficult to maintain. Mobile devices are a good example. These operators allowed users to choose only their own applications and services. Now that such phones access the Internet, consumers can find other sources. Most phones put limits in the device software, but hackers often defeat them. For example, telephones are often tied to a given service - in the United States, Sprint, Verizon, or T-Mobile. But on eBay, consumers can buy “open” phones (devices that have been modified to work with any service).

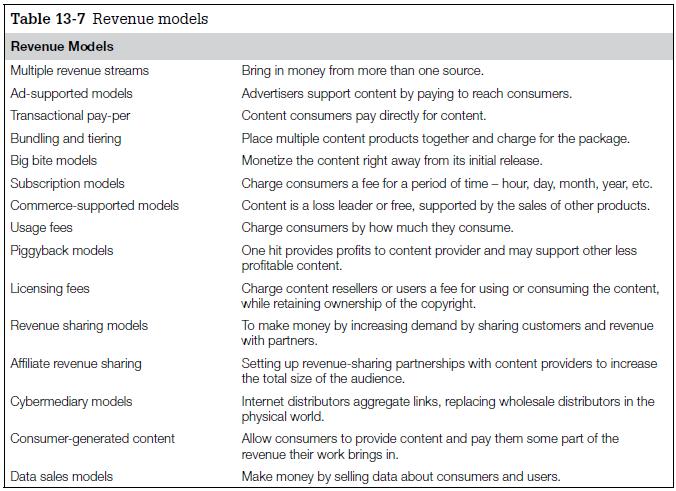

REVENUE MODELS

People will pay for content they want. Timeliness and time-to-market are always important, because information and entertainment products are highly perishable, like fresh flowers or lettuce. Freshness is especially criti-cal for financial and business information, and companies and investors are sometimes willing to pay considerable sums to get it first. People like to be the first to receive entertainment but, more important, like it to be - well— entertaining.

Revenue models deal with product packaging, pricing, mechanisms for receiv-ing money (or services in the case of barter), and revenue sharing schemes. Many of the models used by traditional media carry over into the digital mar-ketplace. Not surprisingly, there are usually some unique twists when this analog to digital conversion takes place. Revenue models in new media mar-kets may have the same name as those used in traditional venues, but they often mean quite different things. For example, pay-per models can cover smaller informational pieces than in the cable industry, which typically mar-kets whole programs.

Of all the parts of business models, the list of revenue models is the longest. Perhaps this makes sense, in that business is primarily the pursuit of profit and nothing is more important to that effort than how the enterprise will make money. As the content business landscape continues to evolve, under the pres-sure of technologies, there is probably no way to capture all the possible rev-enue models. In addition, they can be combined into a nearly limitless set of combinations. Table 13-7 lists the more common revenue models.

Multiple Revenue Stream Models

It is hard to think of a content-based business that does not have multiple revenue streams and that does not spend considerable effort developing them. The over-the-air broadcast industry relied heavily on advertising budgets, but early in its development, began selling programs into the syndication market to add an additional stream of income. Today, successful programs become series DVDs as well.

The value of multiple sources of revenues in media and entertainment became clear to broadcasters with the rise of the cable industry as they competed with TV programming providers that could deliver multiple channels and brought in receipts from monthly subscriptions, advertising, premium channels, pay-per-view, and high-speed Internet access and telephony. Music labels have dis-covered the downstream market for ringtones based on popular songs. And some popular motion pictures make more money from ancillary merchandis-ing deals than they do from the box office.

Ad-supported Models

Advertising is the stalwart of over-the-air television and a major source of reve-nue for basic cable and satellite channels, through 30-, 20-, 15-, and 10-second commercial spots. It is increasingly important to Internet Web sites as one of several sources of revenue. Marketers can buy a place on a Web page, usually the home or landing page. These availabilities include space for banner advertise-ments, pop-up windows, streaming video button boxes (V-boxes), and click-on animations, logos, banners, and buttons for audio clips. Sponsoring a Web site will give an advertiser access to all these forms of placement as well.

In traditional media, audiences are sold to advertisers on a CPM (cost per thousand) impressions. On the largest Internet sites that command millions of visitors, such as AOL and Yahoo!, this formulation works well. However, on the majority of Internet sites, advertising rates are less certain. Even though sites deliver customers with specific demographic and psychographic profiles, and their behaviors can be monitored and recorded, measurement issues still cloud the picture. Many new ways of accounting for customer behavior online now exist, as shown in Figure 13-4.

One controversy is that of impressions versus click-throughs. Internet Web site operators want to be paid for the number of targeted consumers they bring to the site. They have no control over the effectiveness of the ad itself, so they believe the number of site visitors should be the key metric. Advertisers prefer paying for click-throughs or sell-throughs.

The Internet Advertising Bureau issued guidelines for measuring a digital video ad , an ad that appears in streamed media, games, and other digital venues.15 The group will continue as digital media evolve. They hope to standardize measurement and reporting procedures that will be necessary for the Internet to capture a substantial share of advertising budgets.

When high-speed broadband access becomes more widespread, advertising will play an important role in supporting content for it. Video and audio are much more expensive to produce than text and graphics, and broadband dis-tribution will make content providers more dependent on commercial rev-enues to produce and distribute popular material - not that anything is likely to replace the Internet’s current rich stew of irreverent, zany, flippant, obscene, snotty, thoughtful, and silly user-generated content.

Transactional Pay-per Models

Long before the term pay per came into being, people paid per ticket to attend movies, plays, and performances. Then telephone companies introduced pay-per-minute charges for long distance and local long distance. Cable systems launched pay-per-view service, which in the case of the NBC Olympic coverage was extended to mean pay-per-event or pay-per-package. And the advent of videocassettes and players brought about pay-per-night rentals.

Pay-per models are attractive to both buyers and sellers, and there are various Internet services that offer pay-per-download, pay-per-bit, per-article, per-photo, per-song, and per-video. The main problem with many of these schemes is that of micropayments , small transactions that are more expensive to meter and collect than the value of the payment. Until some form of digital wallet technology is standardized, it is likely to be difficult for content providers to make money on small units of information. However, the increasing automation of payments are coming close to providing this service, as evidenced by the growth of PayPal.

Bundling and tiering

Bundling and tiering are pricing as well as marketing models. They are well-developed strategies by multichannel TV providers, but less used in other envi-ronments. Most bundling and tiering are implemented by product type - motion pictures, sports, or some other popular content genre. The more popular prod-ucts cost the most, followed by ever-less-popular material. It is also possible to create bundles (or packages) and tiering based on timeliness so that the first buyers pay more than later buyers, when the material may be less timely.

The cable industry provides an excellent example. The first tier is basic cable. The second tier is composed of extended basic packages, each one costing an addi-tional monthly fee. The third tier is made up of individual premium channels; the fourth is a digital tier of bundled channels; and next tier is pay-per-view, which charges for receiving individual programs, usually movies and sporting events; and the most expensive tier is individual on-demand viewings, usually motion pictures. High-speed Internet access and telephony are not considered a tier - they are added services. However, they are often bundled with cable services to provide an overall lower package price.

Big Bite Models

Big bite models are the opposite of windowing, which monetizes content by releasing it in stages to different distribution systems. “Forget windowing. It’ll never work in the age of digital recreation and redistribution,” cry the propo-nents of this model. Instead, they argue that content owners must monetize the first bytes out of the box and move on. The motto might be, “Eat the apple, then toss the core, because if the product can’t make a decent profit when it first rolls out, it will probably incur a loss.” Content providers have to get the money while the getting is good - immediately. As soon as the product is widely available on the Net, its sales price will quickly drop to zero. Packaged video games are a good example: It takes 18 months to 2 years to create them and a couple of months to sell them out - or to bulldoze under the unsold product.

Subscription Models

Tiering is frequently an adjunct to subscriptions, but not always. A subscrip- tion is a revenue scheme where the subscriber pays an agreed upon amount for specified content for a fixed period of time. In the cable world, system operators charge a monthly fee for the basic tier but per-channel/per-month fees for pre-mium channels. Many online games charge a monthly subscription. So do Internet service providers and many Web site hosting services.

Commerce-Supported Revenue Models

Content attracts people, so some marketers use it to draw customers for other products. When the material is sold at a price cheaper than the marketer paid for it or given away for free, it is called a loss leader. However, the content was probably sold at a profit to the copyright holder. Wal-Mart and Target used music CDs and video games as loss leaders. Apple uses iPhone applications to increase the value of its product, so that the thousands of applications give customers additional incentives to buy the phone.

One of the advantages that the Internet offers is that it is actionable, meaning that it can be acted upon immediately. On the Internet, a click and a credit card are all that are needed for a purchase. Contrast this ease of purchase with tele-vision and radio, where the viewer or listener has to drive to a store or place a phone call and execute a long series of actions to get a product. For this reason, e-commerce models are not suitable for one-way media; they apply only to interactive platforms such as the Internet and interactive TV.

One way designers conceptualize the development of Web sites is “wrapping e-commerce opportunities around content.” So it is no surprise that there is some discussion that user-generated content may be the new loss leader to sell commercially produced content, evidenced by new Internet deals signed by some social media sites.16 Efforts to push e-commerce using free content may be subtle sidebars or links, or they may be the obnoxiously intrusive pop-up windows, such as those employed by Netflix, consistently reported by users as the most disliked form of online advertising.

White papers and free reports are often underwritten by companies who want to establish themselves as opinion leaders in their market. They offer the infor-mation for free, using the registration process to gather information about pos-sible customers. After the information has been downloaded, a salesperson uses the contact information to follow up.

Usage Fees

Usage fees are charged for time or a service. Typically they take the form of a flat service fee, network utilization fees, or access fees, as shown in Table 13-8. Often flat fees are designed to include costs incurred for network utilization or access. A good example is the mobile telephone industry. Users often pay a flat service for a bucket of minutes. However, that bucket includes the costs paid by the phone service provider for use of the wireless spectrum.

When a customer pays for individual long-distance calls, they are typically network utilization fees , charges for using the long-distance network. Hidden in these charges is a network access fee , paid by the local phone operator. Another example is mobile broadband service Internet access offered by Sprint, Veri-zon, and AT&T in the United States. The operator charges the customer a flat service fee , although the operator pays a network utilization fee. At a hotel, customers often pay a daily fee for use of the Internet - this charge is a network access fee.

Piggyback Models

This model is a strategy of having one content product or service supporting the other content offerings. In the motion picture and television businesses, it is not unknown for a few successful hits to carry a studio, production com-pany, or network for some length of time. A special case of piggybacking is the tentpole scheduling strategy, used by broadcast television networks. It means scheduling a popular show with high ratings between two new or lower-rated shows so that the tentpole show carries the two less popular shows - giving them a chance to build an audience.

Licensing Fees