]>

CHAPTER 9

CONTENTS

Chapter Objectives... 223

Introduction.............. 223

Defining the Content Product....... 224

Channel Marketing... 231

A Day in the Life of Elliot Grove ......... 232

Pricing Strategies: We Do Windows...... 239

Summary.................. 241

What’s Ahead........... 241

Case Study 9.1 Details, Details......... 241

Case Study 9.2 You Package the Goods.................. 242

References................ 243

By the age of six the average child will have completed the basic american education. … From television, the child will have learned how to pick a lock, commit a fairly elaborate bank holdup, prevent wetness all day long, get the laundry twice as white, and kill people with a variety of sophisticated armaments.

Russell Baker

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

The objectives of this chapter are to provide you with information about:

- Defining the content product

- Packaging the product

- Content’s long tail

- Real-time content

- Bundles and packages

- Brand extensions

- Formats

- Licensing

- Channel marketing

- Screens

- Wholesale mechanisms: Partners, distributors, and aggregators

- Retail outlets

- Direct-to-consumer and Customer Relationship Management (CRM)

- Pricing strategies: We do windows

INTRODUCTION

The previous chapter looked at the big ideas and issues that face marketers in the content industries. This chapter carries the discussion further: “into the weeds” of the marketing process, the channels, the sales venues, and pricing and payment.

DEFINING THE CONTENT PRODUCT

A movie’s revelations, a favorite TV show, a song you danced to when you fell in love … some of life’s most important moments are tied forever in our memories to the media that captured our attention at the time. Calling them “content” or “products” hardly seems to do justice to these powerful triggers of significant remembrances! Yet just as a fine steak is a profitable menu item to a restaurant manager, so is a motion picture, television show, or song, no matter how emotionally moving or technically brilliant, a product or a property to content industry professionals. On a personal level, they may be affected just as a consumer would be. But on the professional level, they must evaluate the material and make solid plans about how to turn it into a successful, profitable business venture.

Almost everyone dreams of writing a book, a screenplay, a song, or an influential blog. And many of them follow their dream. Some labors of love, made out of a desire to see the work created, may achieve commercial success, but there are very few: The vast majority of profitable content efforts are created as commercial products that are intended to appeal to a defined audience and market. Thus, from the very beginning, the creation of professional content products takes place with marketing in mind.

Of course, other factors come into play as well, including genre, innovation, and creativity. Content industry segments tend to develop particular genres of content, as shown in Table 9-1.

Packaging the Product

The bare content (a song, a screenplay, a book, a video, a white paper) itself is just the beginning. It is a creative work - a property - but it is not yet a product. In order to turn a creative work into a commercially viable product, it must be packaged. Packaging is one of the first steps in marketing, a way of shaping the content to appeal to specific segments of the market. Such shaping is essential to insure profitability. In other words, the prospective audience in the aggregate must pay more than it cost to produce, market, and distribute the material, so that all those who participated in that process (or value chain ) will share in the profits. Once the content is packaged for maximum appeal and formatted in an appropriate manner for distribution, then the marketing experts have an offering they can make available to a potential buyer, user, or consumer.

“Packaging” has different meanings in different contexts:

- In industries that sell hard goods (toothbrushes, tea, and tents), packag-ing means to enclose or protect products for distribution, storage, sale, and use - the familiar plastic wrap, boxes, and clam-shell wraps that pose such a challenge for consumers to open.

- In the motion pictures industry, it means putting together a combination of the major stars and creative personnel who will to work on or appear in the film. This “package” is used before production to raise money from investors and to arrange for presales to distributors.

- In television and other media that produce shows, programs, and videos, packaging refers to all the graphic elements that surround the actual program: intros, outros, bumpers, mattes, lower thirds, and credits.

- In the cable and satellite industry, packages usually mean a group of net-works or programs that are bundled together, often offered at a special price.

All these definitions have one element in common: They are a way of “wrap-ping” the product for sale, whether it is a material wrapper or a digital wrapper. It’s not only package materials that differ; so do the means of affixing them to the product, the manner in which they are removed, and the role they play (protecting, explaining, decorating, and promoting).

Increasingly, developing the content and its packaging is not just a case of the con-tent creators producing a product and then marketing it to some audience segment. Many companies think of it as co-creation, where creating content is a conversa-tion between creators, marketers, and consumers. In practical terms, before mak-ing a decision about what to produce, marketers often solicit potential prospects for their ideas and suggestions about how to design the content. At minimum, producers ask likely consumers to view the versions of the product with alternative packaging wrapped around it, comparing their responses to each possible con-figuration. This research may take place by depth interview, focus group, or special showing or exhibition and, based on the results, marketers can have more confi-dence in the final packaged product they will place before consumers at large.

A new feature of contemporary content marketing is to make the delivery mode a feature offering. It’s a philosophy that says to make it easy and convenient to access the content - giving consumers the content how they want it, where they want it, when they want it. For example, a viewer can watch a motion picture through an on-demand television service, rented or purchased DVD, streamed live over the Internet, or downloaded from the Internet.

Content’s Long Tail

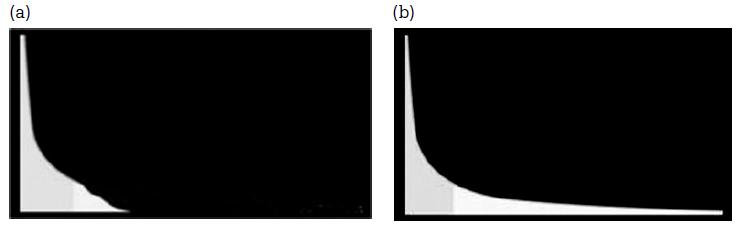

Hits, fads, and fashions move at warp speed around the world, spreading across the global Internet.1 Back in the day, people said, “Here today, gone tomorrow.” Now, as Chris Rock observed about the contemporary music business, people say, “Here today, gone today.” It’s true that as a hit, a song or a program may be gone. And yet, because of the long tail, content only appears to be gone; it may only be in hibernation, waiting to return in a new season. Figure 9-1 compares how traditional content marketers thought about the life of content over time: It’s a hit, then it dies. However, things have changed, and that formulation no longer captures an important feature of the market for content, the long tail of content, identified by Chris Anderson.2

FIGURE 9-1 (a) Traditional consumer purchase behavior of content products and (b) new content long tail. Source: Hay Kranen

In the beginning was content with no tail, or only a short tail. Marketers who worked in traditional mass media did not commit many resources to market-ing programs. Instead, they used their own media platform to promote their products to the mass audience already watching. Because that audience didn’t have a lot of entertainment choices, it was not unusual for a hit show to attract 30 or 40 percent of the available audience. And marketers were aggressive in pitching their audience to advertisers. When a program stopped attracting, producers or networks packaged the shows for syndication and sold them as packages for additional runs on independent local stations. After a few years, the programs became so well known that they stopped attracting an audience and were retired altogether.

The technologies of television distribution make it cost-effective to send the same program at the same time to millions, even billions of people. Over-the-air broadcast television and satellite are one-to-many (or point-to-multipoint) transmission systems - it costs almost the same to send a program to five peo-ple as it does to send it to five million people. Originally, cable networks were designed the same way; instead of transmitting from the local TV station, the local headend pushed programs to TV households.

Now, content lives forever, or for so long that it approximates forever. The long tail of content became possible in the past two decades because of several advances. Cheaper digital storage made it possible to store a vast array of con-tent products, both by individual sites and collectively, the totality of Internet Web sites. Cheaper transport over the Internet made it possible to send that content on demand to any individual consumer, at a reasonable price. And cheaper online on-demand payment processing reduced transaction costs to an acceptable level for both buyers and sellers.

When consumers can choose from a more or less unlimited catalog, they choose carefully and precisely, buying exactly what they want, without com-promise. Anderson reported that in just about any huge catalog, 98 percent of the properties will be ordered.3 It’s true that a large proportion of sales accrue to hits - popular content that almost everyone sees. But, taken together, the total sales of properties extending out on the long tail will bring in as much or more revenue than the hits. Anderson argues that this trend will continue and that, over time, blockbusters will exercise a less powerful influence over the content market.

For example, Aris and Bughin4 reported that Amazon makes almost half of its revenues from niche books that were previously unmarketable because the cost of maintaining such a huge inventory made it impossible to sell such books at a profit. However, they also make the arguments that managers must have a robust strategy for hit properties. One reason is that not only do current hits dominate the market of the moment, but past hits also account for a large percentage of

It is becoming increasingly important to manage the existing stock of content and rights - the back catalog - aggressively to achieve maximum revenues over its lifetime. More than ever before, media companies will have to ensure that they have the rights and ability to exploit the full commercial potential of existing popular formats and brands. There are many opportuni-ties to do this, depending on the media segment. For example, in the case of TV shows, reruns, relaunches, and spin-offs; in recorded music, the release of best-of albums and backlist compila-tions; and, in all sectors, vertical and horizontal brand extensions and leverage for nonadvertis-ing revenues, such as content-branded merchandizing.5

sales of long-tail content. In other words, a hit today is a solid seller tomorrow, next year, and over the next decade. So though the influence of hits may lessen at any one point in time, marketers must still groom properties for large-scale sales.

Real-Time Content

Real-time content is a special genre that must be considered in a different light from other content genres. The category includes radio and television news shows, talk shows, sports, and live event coverage, traffic, weather, sports, and news and sports networks. Above all, one common characteristic of real-time content is that it must be timely to be successful.

Recent years have affected the markets for real-time content in very different ways. Some sectors are enjoying all-time high revenues; others are doing badly, facing severe budget and personnel cuts, and even bankruptcy. Generally, this content genre must be profitable in its first run because it does not sell as well along the long tail as other types of material.

Real-time content may be entertainment, such as sports and talk shows, or information-based, including news, traffic, and weather. The entertainment formats are maintaining their profitability and popularity - and even growing. Reality shows did well in 2008.6 And for sports, 2008 was an extraordinary year on television, radio, and online.7 There was a string of most-ever-watched sports events, including the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing with 4.7 billion view-ers, the Super Bowl, cable broadcast, cable golf events, cable baseball games, NBA finals, NHL regular season games, and Wimbledon Finals. The Nielsen Company attributes these successes to:

- Compelling narratives

- High-definition-television picture quality

- More availability through more sports networks and Internet and mobile technologies

- Growing popularity of fantasy league sports

- Global market

By contrast, news presents a mixed picture that many people find worrisome because of the importance of journalism to democratic societies in inform-ing the public. According to the Pew Project report, newspaper revenues fell 23 percent between 2007 and 2009 and the overall financial condition of the industry is dire.8 Local television news revenues fell 7 percent in 2008 and ratings continue to fall. Network news audiences continued to fall, although more slowly than in the past. However, in some instances, the picture is begin-ning to improve. Cable news networks and some network news programs have shown audience gains, particularly those that display a “seriousness of pur-pose, a sense of responsibility and a confidence that the significant can be made interesting,” notes the report.

It is not clear that the problems experienced by poorly performing real-time content can be solved through marketing - however necessary it may be. To some critics, news operations are adversely affected by the emphasis on the pursuit of market share and revenues, creating tabloid news cover-age that emphasizes celebrity and other trivial stories.9 Even the strongest supporters of today’s news providers agree that companies must address changes in consumer habits and lifestyle, the overall economy, industry cost structures, and outdated business models before marketing efforts can succeed.

Bundles and Packages

Recall that, once produced, the additional (marginal) cost of providing con-tent to one more consumer is negligible, essentially the cost of delivery. As a result, it is common for content companies to put several properties together in a package or bundle. They may aim to fulfill several marketing objectives through bundling, such as:

- Creating a viable product

- Reaching a larger audience by combining the appeal of the bundled products

- Creating price tiers

- Offering a price discount

There are many examples of bundles. The owners of popular television shows, such as HBO’s Sopranos and ABC’s Grey’s Anatomy , package together a bundle of all the episodes shown during a television season for rental and sale from video stores and Web sites. Software companies often bundle products together. For example, users who buy Sony Vegas Pro® video editing software also receive NewBlue Cartoonr® . Cable and satellite operators bundle together many channels into programming tiers, such as the basic tier; the enhanced basic tier; and drama, sports, and premium tiers. They also offer special promotions of premium chan-nels like HBO, Showtime, and Starz by adding a second channel for a lower price for a period of time if the subscriber orders one premium channel. This offering is particularly good for increasing the sampling of new channel offerings.

Brand Extensions

Content companies launch brand extensions to use existing successful content to reach new audiences. Extending the brand essentially means extending the market. There are two kinds of brand extensions: horizontal and vertical.10 Hori-zontal brand extension means applying an existing brand name to a new prod-uct, which can be in a related category or entirely new to the company that is introducing the product. Vertical brand extension means introducing the prod-uct in the same category as the core brand, but the offering differs in some way, perhaps with different pricing, level of quality, focus, or features. Step-up vertical extensions mean the new product is an improvement or upgrade; a step-down vertical extension means the price or feature set of the new product is reduced.

Content industry horizontal extensions include turning a motion picture into a TV show or a Broadway musical, such as Disney’s Mary Poppins, The Lion King, and The Little Mermaid. It could also mean the reverse, such as when Fox created a step-up vertical extension of the popular TV series The X-Files into a motion picture. Vertical extensions include movie sequels and prequels, TV program reruns and spin-offs, recorded music best-of and compilation albums, and software upgrades.

There may be risks to extending a successful brand.11 Introducing a step-down vertical brand extension can hurt the core brand by taking away sales of the core brand, a process called cannibalizing. For example, pay-TV subscribers who might have otherwise gone to a theater and purchased an $8.00 ticket per per-son to see a motion picture may elect to wait for the movie to come to the on-demand service, paying from a few dollars to as much as $10 for at-home viewing. Essentially, the lower-cost option cannibalized the higher cost sale. Another risk is that the new product will be perceived as being of lower quality than the core brand. Public disappointment in sequels is common.

Step-up extensions can be problematic too. Consumers may become confused. Or the new product may make them uncertain about the quality of the core brand product. They can ask, “What was wrong with the original product?” or “Why wasn’t the higher quality available in the original?” Such questions are particularly common in software upgrades, seen with such products as Micro-soft Windows® .

Licensing

When content companies consider horizontal brand extensions - using the core brand to introduce products in an entirely different product category or industry - they often turn to licensing, rather than producing and marketing

Prior to Star Wars, merchandising was used only to help promote a movie and rarely lasted after the movie had finished its run. But Star Wars merchandising became a business unto itself and produced the most important licensing properties in history. The commercialization of Star Wars can be seen everywhere, from action figures to comic books to bank checks; there are even Star Wars -themed versions of Monopoly, Trivial Pursuit, and Battleship. Kenner toys once estimated that for most of the 1980s they sold in excess of $1 billion a year in Star Wars -related toys. In 1996, Star Wars action figures were the bestselling toy for boys and the second overall bestseller, after Barbie; in 1999 Legos introduced new models based on spaceships from the early movies. Even in the late 1990s, Star Wars toys based on the original trilogy before the prequel remained incredibly popular.12

the new product. Licensing is ample proof of the power of intellectual prop- erty, and the all-time champion of licensing is the Star Wars franchise.

The first three Star Wars motion pictures brought in about $2 billion in box office sales and more than $4 billion in merchandising. The prequel, Star Wars I: The Phantom Menace was an even more astonishing earner. Pepsi paid $2 bil-lion to license the brand and Mattel paid $1 billion for a 10-year toy license. The soundtrack alone sold 1 million copies in its first pressing. A year after the film was released, students from a UCLA class counted 31 Star Wars -branded products in a local supermarket.13

CHANNEL MARKETING

A channel is navigable passage - the bed of a river or stream, a path for elec-trical signals, a route through which anything may pass. Marketing channels are ways of promoting and selling content products - the deals - that precede the distribution of content from license holders to consumers. The commer-cial pathways of content markets include existing wholesale, retail, and direct channels between marketers and consumers in some sectors of the content industry, while other channels are still being forged.

In the traditional motion picture and television segments, which have been around for decades, the wholesale mechanisms for marketing and delivering content are well developed. Internet and mobile marketing channels are still under construction. Direct channels, though well understood within some industries, are generally unfamiliar to most film and television practitioners. A content marketer might adopt a wholesale marketing channel strategy by licensing it to a syndicator, who in turn will mark up the price and relicense it to another syndicator or distributor or directly to an exhibitor. The exhibitor then delivers the content to the consumer, or they may choose a direct-to-consumer channel or some combination of both.

A DAY IN THE LIFE OF ELLIOT GROVE

Elliot Grove, Director and Founder of the Raindance Film Festival and the British Independent Film Awards http://www.raindance.org ; http://www.bifa.org.uk

I grew up in an Amish Mennonite community outside Toronto and was taught that the devil lived in the cinema. One day, when I was 16, I was sent into town to collect some weld-ing from the blacksmith and had 3 hours to kill. So I walked up and down, and decided to see what the devil looked like. I paid 99 cents, went in, and sat down - it was a bit like church, except the fabric on the seats was red: the colour of the devil. Then they turned the lights off. The first movie I saw was Lassie Comes Home , and I wept like a baby. At the end I went up to touch the screen to see if I could feel the rocks or the fur - but it was gone, magic. And I was hooked on cinema forever.

I started Raindance in 1992 during a personal low. I had just gone bust in the previous global recession and I spent a long time feeling sorry for myself. I decided to retool in film - I had lost all my previous film contacts made while I was a scenic artist, and started a film training programme here in London. A year later I started the Raindance Film Fes-tival, and in 1998, when the British film industry was wal-lowing in self-pity, I started the British Independent Film Awards.

My typical day starts by unlocking the office. More often than not I am the first one in. I love switching the lights on; it reminds me of that first frame of Lassie Comes Home that hit the screen. I open up my email to see if there is anything urgent or exciting. A colleague or two usually show up a few minutes later, and while they are settling we have an informal chat which covers these three really important things: what happened yesterday that could be better, what’s happening at home (a couple of Raindance workers have small children; a couple others are single, so there is always plenty to dis-cuss), and lastly, what’s on the agenda today. These are really special moments, and if someone is late, or away, you really miss them.

The interns start arriving - we usually have four. I try and give each person a special project that plays to their strengths. Some interns excel in physical/practical things, others are really good on the telephone, and others have good web skills. I then have my second meeting of the day - with the interns - and again we discuss yesterday/last night at home/today.

I then check the metrics on the Web site: the number of new Twitter followers, unique visitors to our Web site, and how many people have opened our emails from the day before. It gives me a perverse pleasure to check these statistics - I’m never sure what they mean, but it is fun.

I have three problems each day. In fact, I don’t like to call them “problems” - I prefer to say that in general I face three challenging creative opportunities:

- 1. As an art-based charity, we need to be very focused on money.

- 2. Administering our hectic training programme and the oldest, largest independent film festival in Europe.

- 3. Political issues. This area has started to demand a lot of my time, partly because we have grown in stature, partly because our competitors persist at taking cheap shots at us, and partly because of my own ego. I am terrible at politics - perhaps it is the pacifist teaching I got as a youngster, the “turn the other cheek” approach that Mennonites are known for. I try to assess the challenge and delegate our response to a colleague more adept and astute than me.

I know I have had a good day when everyone in the office has been totally immersed in their work. I love it when some-one, intern or staff member, shouts, “Whoopee! Look what I found!”

Of course Raindance as a company has financial targets and goals like any other business, from dry cleaning to den-tistry. But an important aspect of our goals, and my goals personally, is to help other filmmakers. Every once in a while we get a big slobbery thank you and that really makes it all worthwhile.

After the interns go home, I either have a speaking engagement somewhere in the city, or I go home to catch up on writing (like this) or I Twitter, or I watch yet another inde-pendent feature or short by someone, perhaps exactly like you, trying to break in. When I find something special, I feel like I have had the best day ever.

It doesn’t get better than that.

Vertical channels are all the available marketing paths within a single industry - the windows of opportunity that will be discussed in detail later in this chapter. Some-times marketers will say, “I’m handling the syndicator vertical,” to indicate their specialty. Most content industry marketing is done through vertical channels but horizontal channels add additional lucrative revenue streams as well. Horizontal channels are ways of marketing to other industries. For example, motion pictures and other programs might be available on aircraft through airlines or in hotel rooms through an aggregator for that industry, such as LodgeNet. The education market is another horizontal market, particularly for documentary and news content.

Screens

People seek content products through screens - even iPods have a screen. And increasingly, they consume media through them, too. Each screen has differ-ent format requirements and perhaps consumer usage patterns as well. Even books, magazines, and newspapers may soon be seen on screen devices such as the Amazon Kindle. The screens of interest to content marketers are:

- The big screen: Theaters, IMAX, and drive-ins

- The small screen: Television

- The smaller screen: Internet

- The smallest screen: Mobile telephones and devices

Wholesale Mechanisms

Market structures typically support four types of channels: wholesale (dis-tributors, syndicators, and aggregators), retail, direct business-to-business, and direct business-to-consumer. Filmed entertainment content is more often licensed than it is bought and sold, although the purchase of entire libraries is not unknown. Typically studios and television production companies create content and license it to distributors or syndicators or directly to domestic and foreign exhibitors, such as local stations, broadcast groups, and cable, satellite, and telephone operators. In today’s market, they may also make deals with Internet and mobile content distributors.

Each of the four content screens has its own set of marketing channels that have grown up around it. At the wholesale level, marketers in the motion picture and television industr participate in a structured series of conventions, trade shows, and private meetings with middlemen to put their content before con-sumers, as shown in Table 9-2. The television industry promotes programs to consumers and also markets audiences to advertisers. (Marketing to advertis-ers requires a separate set of trade events, meetings, and contractual relation-ships with independent media rep firms. Rep firms handle spot sales, unreserved commercial availabilities that are left after up-front sales that reserved time in advance for advertisers to place their commercials.)

A great deal of business takes place at trade shows. Equally important is that marketers have the opportunity to meet potential customers face to face and to establish personal relationships. At international shows, they may be able to find partners who can provide marketing expertise in geographies where a content owner may wish to offer content to the public. Executives can walk around the show floor and spot trends and gather competitive intelligence that will prove important to their company.

In large markets for any kind of product, goods reach consumers through a supply chain. The supply chain stretches back to the raw materials that go into a product. The links forward include the product producer, one or more whole-salers or middlemen, and the retailer. The content supply chain works the same way as it does for other products.

Content companies may market their content through middlemen (partners, distributors, syndicators, and aggregators). For example, television production companies create a program and license it to a broadcaster for a certain num-ber of showings, usually on an exclusive basis for a set period of time. After that license expires, the production company can again license the content to distributors or syndicators. Or it may bring the content to a program market and sell directly to an exhibitor, such as a local station, a broadcast group, cable and satellite operators and networks, and foreign television networks. In a wholesale transaction, the copyright holder to the content product might license it to a syndicator, who in turn will mark up the price and relicense it to another syndicator or distributor or directly to an exhibitor. The exhibitor, perhaps an independent station, then delivers the content to the consumer.

As discussed in Chapter 2, some large media and entertainment companies are vertically integrated. In addition to production studios, production services, and other production-related facilities, they own distribution units and many own media platforms where they can deliver content directly to the audience. As detailed in Chapter 2, they may own networks, stations, or cable companies.

In addition to the majors, there are thousands of distributors and exhibitors. Lacking the integration of the largest corporations, they take advantage of tra-ditional marketing channels for buying and selling content. The attendees of such markets typically include sellers, suppliers of finished programs, pack-aged TV channels, and formats, and buyers, programming, acquisitions, and co-production executives representing TV stations, pay-TV operators, DVD and theatrical distributors, broadband and telephone company operators, web por-tals, closed-circuit networks servicing airlines, and retail points of sale, produc-tion companies, and territorial agents. Finally, when television programming is on offer, the attendees include advertisers, advertising and media-buying agencies, and direct marketers.

Everyone knows what finished programs are, but what are packaged TV chan-nels and formats, which are also purchased at such markets? Packaged TV channels include a lineup of shows and programming buyers can schedule as a complete channel. It could be a channel dealing with cooking, golf, business, old TV shows - any theme. The key is that it is a channel that can be placed in a slot and airs a negotiated number of hours at a specified price.

Formats are not shows at all; rather, they are a design for shows - they are pure intellectual property and potential rather than actual content. A television program format is a license to produce, exhibit, and distribute a national version of a copyrighted program, using its name. They now make up a large part of the overall TV program market, accounting for about $3.5 billion in sales in 2007.14

The success of format sales has occurred for several reasons. Producers can avoid much of the risks and costs of creating original programming. Moreover, some program genres - comedy, reality-based programming, and game shows - do not travel well. But the pattern of such programs often do very well in many markets. Indeed, game shows make up 50 percent of global format airtime.15 For example, successful shows created in the United Kingdom and recreated for the U.S. market include Antiques Roadshow, The Office, and American Idol. Shows created in the United States that did well in the United Kingdom are Candid Camera, Jeopardy! , and The Apprentice.

The get-togethers where the buying and selling of content take place are called markets. Some venues specialize in particular content genres. MIP-TV, a market for programming of all types, and MIPCOM, a market for entertainment pro-gramming, are held in October in Cannes, France. MIP-Junior, a showcase for children’s and youth programming screenings, is a specialized part of MIPCOM. MIPdoc is also held in Cannes but in April; it is a showcase for documentary work. MIDEM, a market for recorded music, is held in Cannes, just before the various MIP events. MIP-Asia occurs in December in Singapore.

The National Association of Television Programming Executives holds a Janu-ary convention where buyers and sellers discuss industry trends as well as make deals. In recent years, NATPE has been held in Las Vegas, but it is not tied to that city. NATPE also organizes specialized geographic programming markets, DISCOP East, occurring in June for television outlets in Central and Eastern Europe, and Eurasia, and DISCOP Africa in February, covering that continent. Other key markets are the London Programme Market, held in November in London and the Monte Carlo Television Market, taking place in February in Monte Carlo, Monaco.

The practice of buying multiple episodes of a television program in a bundle is called syndication. Off-network syndication means that the program originally ran on a broadcast network, where successful ratings increase the attractiveness and price of deals for subsequent plays. Because producers can typically recover only 80-85 percent of the cost of producing episodes, syndication is a key part of their financial estimates of future profitability.16 Domestic syndication of TV series to local stations usually allows six airings over a 5-year period. First-run syndication refers to shows that have been produced for direct-to-market sale without having been aired first on a network. Talk shows often begin as first-run syndication offerings.

Motion pictures may be offered at television markets, but there are also specific venues for movie deal-making. The American Film Market (AFM) held in Novem-ber in Santa Monica, California, is the world’s largest market for films, where independent filmmakers make deals to bring their movies to consumers. Such films often start their journey to market via exhibition at the premier festivals, such as the Sundance Film Festival:

over 8,000 industry leaders converge in santa Monica for eight days of deal-making, screenings, seminars, red carpet premieres, network-ing and parties. Participants come from over 70 countries and include acquisition and development executives, agents, attorneys, directors, distributors, festival directors, financiers, film commissioners, produc-ers, writers, the world’s press, all those who provide services to the motion picture industry.17

Retail Mechanisms

Motion picture and TV program DVDs, videogames, computer software, music CDs, and even books are for sale in video rental stores, supermarkets, drug-stores, 99-cent stores - just about everywhere. But the most voracious appetite for content comes from the big-box retailers - Wal-Mart, Costco, Best Buy, and other large warehouse stores. In the case of videogames, a wholesale purchase by big-box retailers can make or break a title.

Big-box retailers are not easy for entertainment marketers.18 The relatively low price of content means that it may be used as a loss leader , a product sold at a low price to attract customers to the store. They demand that every product be given a unique identifier, an SKU (Stock Keeping Unit), which adds additional steps to distribution. Increasingly, they want each product to be identifiable with a radio-transmitted ID, called RFID (Radio Frequency Identification), which would add to the price as well as the distribution task. There are dis-agreements about returned products and customer complaints, which the big-box retailers want content companies to handle. Other retailers do not sell on the scale that the big-box stores do, but they aren’t as demanding, either.

Now there is the Internet, which is proving to be a formidable competitor to video stores, and many analysts believe the brick-and-mortar venues will not survive. Hybrid services like Netflix, a low-cost subscription service (that starts at $8.99 per month) that allows customers to order over the Internet but receives the content on a DVD through the mail. With the DVD comes a return envelope. Other Internet services allow the customer to download the content and watch it on their computer or to make their own one-time DVD.

Direct-to-Consumer and Customer Relationship Management (CRM)

Most content companies do not want to market directly to consumers. It involves a considerable organizational infrastructure at some cost to interact with customers and to handle rebates, credits, and product replacements. The relative low product cost of most content products makes it inefficient to set up such units, even on an outsourced basis. Even on the Internet, large content companies drift from their core competency of creating content by taking on direct-to-consumer marketing and sales.

By contrast, media platform providers who have regular subscribers do have customer service infrastructure in place. Cable and satellite operators, Inter-net service providers, and telephone companies receive monthly subscription payments that give them a regular cash flow and allow them to set up routine customer service. Most companies handle such service with a combination of in-house units and outsourced service providers.

Companies that deal with consumers recognize that beyond customer service, they must think of this activity as customer relationship management ( CRM ).19 CRM has an enormous impact on a company’s bottom line. Although mar-keting may be able to attract customers and sales can get them to sign on the dotted line, CRM is essential for retaining customers and reducing churn , or the loss of customers. A well-trained personable customer service representative ( CSR ) will use the customer contact as an opportunity to sell more products ( cross-sell ) or more expensive products ( up-sell ), which, if done on a regular basis, can add considerably to the company’s revenues.

PRICING STRATEGIES: WE DO WINDOWS

Windows is a shorthand way of saying windows of opportunity. It means releasing a motion picture over time in stages (or windows), protected from distribu-tion in any other venue than the one contractually agreed upon by studios and distributors. The order of the windows is determined by the amount of revenue brought in per viewer in the shortest period of time. The strategy was first used by the motion picture industry to maximize its revenues over time. It is essentially a pricing strategy that moves the price down as the property gets older and exhausts its most enthusiastic audiences.

Motion picture windows are well-oiled paths for film distribution, and if that were all they were, it would be a relatively minor matter. However, increasingly, it is worth careful study because it provides a template for many forms of com-mercially distributed content in the future, particularly television program-ming. Given the long tail of content, pricing strategies by controlled window release may ultimately extend to other content types as well.

Movies are first released in theaters, sometimes called fourwalling. Between 4 and 6 months later, they are released on home video for both sale and rental. Four to 6 weeks later, they are distributed on pay-per-view and video-on-demand services. Four to 6 weeks after the pay-per-view window, pictures appear on premium networks like HBO or Showtime, called the pay TV window. Then begins a series of less lucrative TV windows, including distribution to network TV, foreign TV, independent stations, and basic cable networks. The revenue brought in to studios from licensing to television around the world was more than $16 billion in 2003 and nearly $18 billion in 2004, including licensing fees from world pay TV, U.S. broadcast and cable TV, and all foreign TV.20 By the time a property has been distributed in every possible window, the pro- ducers are making fractions of pennies per viewer.

The typical release windows for a film and the revenue each one brings in are:

- Domestic and some international theaters: Individual tickets cost $8-$10 each.

- Other international theatres: Individual tickets cost $2-$8 each.

- Home video sales (simultaneous with rental): $12-$25 each copy, viewing by unlimited number of people.

- Home video rental (simultaneous with sales): $4-$6 per rental, viewing by undetermined number of viewers, but between 1 and probably not more than 50 viewers.

- Pay-per-view/On-demand: $4-$6 dollars per order, viewing by undetermined number of viewers, but between 1 and probably not more than 50 viewers.

- Premium services (Pay TV): $10-$12 monthly subscription, viewing by undetermined number of viewers, but between 1 and probably not more than 50 viewers.

- Network TV: $10-$15 million for presentation to millions of viewers.

- Foreign TV: Networks pay millions for presentation to millions of viewers.

- Syndicated TV: Lowest cost movie packages that are shown to millions of viewers.

Creating Price Tiers

Individual products sell for a specified price and the transaction is over. How-ever, marketing their services by price has proved to be an effective method for multichannel operators (cable and satellite). They have a monthly subscrip-tion business model, differentiated by price tiers for multiple channels as well as individual networks.

Every operator tiers products in their own way, but they share some general pricing characteristics. The basic tier usually includes local channels and other networks with broad appeal, produced at a relatively low cost. These networks are sometimes called minipays because the operator pays the channel from nothing to a few cents to a very few dollars per month, per subscriber, to add the channel to the lineup. (Some channels, mostly shopping channels, pay operators to get on the system and contract for a revenue split as well.)

Another tier that is included in the basic subscription is the on-demand tier. Most operators set aside numerous on-demand channels, providing pay-per-view (PPV) offerings. Typically, PPV revenues are split 50/50 with studios.

The enhanced basic tier adds widely popular channels such as CNN or MSNBC, TNT, TBS, and USA. Most systems have a bouquet of 30 or more networks that entice viewers to pay an additional monthly subscription fee. And the pre-mium tier, featuring pay TV networks like HBO, Showtime, and Starz, adds another $10-$14 per month to the monthly cost.

Price Discounts

With many content items, especially blockbuster movies, consumers have a “first on the block” mentality. They will pay a premium and wait in line for hours to be among the first to see a new Harry Potter or Lord of the Rings release. In this environment, there is no incentive for marketers to lower prices.

However, once the gloss of newness has worn off, price discounts may be an effective marketing tool. A consumer who loved Sleepless in Seattle may buy the DVD on impulse if it is priced at a few dollars. Indeed, this situation is at the heart of long tail marketing, and marketers now have the technological means to maintain the title in a catalog, available from a server that fulfills just this type of content purchase.

SUMMARY

The chapter detailed how program purveyors define content products and how they can sell them. It described the structure of content markets and the venues where buyers and sellers come together to make deals. It looked at how con-sumers access the content via multiple screens and marketer’s pricing strategies to maximize their profits.

WHAT’S AHEAD

The next chapter by coauthor Lisa Poe-Howfield provides a broadcast industry insider’s view of the nuts and bolts. Selling advertising time, avails , to advertisers. Radio and television networks, local stations, and now Internet sites all seek to attract advertisers, selling marketers access to their viewers, listeners, and users. It has a rich ‘how-to’ focus, explaining how sales executives find, service, and retain advertisers.

CASE STUDY 9.1 DETAILS, DETAILS

The ability to package a product is a well-thought-out and carefully planned strategy that marketing experts utilize to attract their target market to the product or service being offered. If done correctly, it simply finalizes the efforts of developing a good product that is branded properly and serves as the final touch to being a huge success. On the other hand, if not done correctly, it can destroy the efforts and investments poured into even the very best of products.

For example, several years ago a company introduced a new healthier bread to the marketplace. The product was branded as home-style, fresh-from-the-oven bread. The advertising was directed at mothers looking for a healthier choice and was designed so that you could practically smell the bread baking in the oven.

So why wasn’t the bread selling? Grocery stores had to remove the product from the shelves. What went wrong? The packaging was green. Why would that make a difference?

Turns out that people generally associate the color green with mold. Yikes. Not what you really want to envision when you’re picking up a loaf of bread for the family. A small mistake that cost the company plenty of dough … no pun intended.

Another company set out to market a new brand of coffee. Hundreds of thousands of dollars were spent on research, establishing relationships with professional sports teams to get it placed into stadiums, not to mention the money behind the actual product of harvesting a special coffee bean in Brazil. When the owners of the company celebrated their first shipment by inviting investors and potential clients to their breaking out party, there was one glaring problem. The beautiful and perfectly placed cup of coffee on the front of the package did not have steam coming from it. It appeared to be a cold cup of coffee sitting on a table. That company ended up going bust because consumers have preset notions about products and even the smallest detail can spell disaster.

Could they have changed the packaging and continued? Yes, but the additional investments needed to recreate the packaging and the lost confidence from the retailers could not be restored.

Business is tough and when given the opportunity to get your product on the shelves, you only have one chance at bat. A product needs to generate a feeling or clear definition that consumers can depend on. It cannot simply be pack-aged in a pretty color; there has to be logic behind each and every element.

It is often easier to recognize the clever marketing strat-egies for tangible items such as cereal, soap, or perfumes. However, when marketing professionals set out to package an intangible item such as a movie, television show, or a syn-dicated radio show, the elements are far less glaring, but they are there - just as the toucan appears on your Froot Loops.

In this exercise, choose a tangible brand product, such as soap, deodorant, cereal, or laundry detergent, that you are loyal to and analyze the packaging:

- What colors were used?

- What words were used to grab your attention on the package (any “new and improved,” “only,” or “first” words used)?

- Did you find any elements to the product that might deter consumers from purchasing?

- Have you seen any advertisements for the product?

- How does that message match the packaging?

Now, for the fun part. Choose one of your favorite television shows, radio programs, or movie and identify the “packaging” for this product:

- What is the tone of this product?

- Are there color schemes used in the TV show or movie that you are able to identify?

- If you have chosen a movie that is now on DVD:

- Describe the packaging and the description of the movie.

- Does it accurately portray the movie?

- What stands out most on the packaging?

- If you have chosen a television show:

- Does it have a theme song?

- Describe the opening and closing of the show.

- Any special elements about the program that makes it unique and appealing?

- If you have chosen a radio program:

- Does it have a themed open and close?

- What does the audience expect to get each time they listen to the program?

- What does this radio program offer that others do not?

- In any of the previous choices:

- Identify who they are attempting to attract to the program. Go beyond demographics. Write a brief description of the type of person you believe will be watching or listening to the program or movie

- Determine whether you believe the marketing experts who “packaged” this show or movie were successful. Support your answer with research that indicates that they have attracted an audience that makes the product successful. If they have not, outline where they fell short.

CASE STUDY 9.2 YOU PACKAGE THE GOODS

After working your way up in the recording industry, you have reached a top marketing management position that puts you in charge of a well-known record label company’s next top artist’s musical release. Your portion of the project will be to successfully package a DVD for this new artist.

Assignment

Step out of your comfort zone on this project. Choose a musi-cal genre that you do not normally listen to. Next, create a name for the band or artist. Begin developing your market-ing plan that will make this a huge success and keep you employed in your dream job. Often, music releases will target multiple potential audiences. Do your research. If your artist is similar to another on the market, what audience do they attract? Do you want to go after the same audience or offer an alternative? If this is your plan, be sure to keep it in mind when moving forward with your future strategies.

Write out a brief description of the collection of songs that will be included on this release. When the consumer purchases your CD, what can they expect to get? Develop a theme for the release and begin making decisions on how you will work with the graphic artist department to design the jewel case for the CD. You don’t have to be an artist for this portion of the exercise. Create a design that would best represent your artist’s release. Do you want to include any special elements inside the packaging? Do you want any of the proceeds to benefit a charity?

At each step along the way, do not forget to keep in mind that the packaging is designed to support any marketing efforts and the product itself - don’t forget the details.

Finally, decide which songs you will release to the market to be played on radio stations with an explanation of why you chose these songs. Create a one-sheet that outlines tour dates and a second sheet that includes a press schedule. What programs or shows would you want your artist to appear on to support this new release? Summarize all of your efforts and share this with your class. Did they catch any details that you overlooked? If not, you are on your way to being a big hit!

REFERENCES

1. Farrell, W. (2000). How hits happen : forecasting predictability in a chaotic marketplace. New York: HarperBusiness.

2. Anderson, Chris. (2006). The long tail: Why the future of business is selling less of more. New York: Hyperion.

3. Ibid., 12.

4. Aris, A. & Cughin, J. (2005). Managing media companies: Harnessing creative value. West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

5. Ibid., 68.

6. Blue, T. (2008). What TV shows earned more viewers. The Insider. Accessed March 9, 2009, at http://www.theinsider.com/news/1461605_What_TV_Shows_Earned_More_Viewers_in_2008_Plus_the_One_Tree_Hill_Anomaly.

7. Nielsen Company (2008). 2008: A banner year in sports. Accessed March 16, 2009, at http://en-us.nielsen.com/main/insights/reports_registered.

8. Pew Project for Excellence in Journalism (2009). The state of the news media: An annual report on American Journalism. Accessed June 2, 2009, at http://www.stateofthemedia.org/2009/narra-tive_overview_intro.php?media=1.

9. Barkin, S. E. (2003). American television news. The media marketplace and the public interest. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

10. Kim, C. K. & Lavack, A. M. (1996). Journal of Product & Brand Management 5:6, 24-37.

11. Ibid., 28.

12. Cobane, C. T. & Damask, N. A. (n.d.). Star Wars. St. James Encyclopedia of Pop Culture. Accessed on May 17, 2009, at http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_g1epc/is_tov/ai_2419101151/.

13. This count resulted from an assignment to attendees of a UCLA Extension School seminar in 2000, sending them to a nearby Ralph’s supermarket to count Star Wars -branded products on the shelves.

14. Altmeppen, Klaus-Dieter, Lantzsch, Katja and Will, Andreas. (2007). Flowing Networks in the Entertainment Business: Organizing International TV Format Trade, International Journal on Media Management, 9:3, 94-104.

15. Buckley, S. (January 22, 2008). The Internet killed the video store. Telecom Magazine. Accessed April 18, 2009, at http://www.telecommagazine.com/article.asp?HH_ID=AR_3884.

16. Aris, A. & Cughin, J. (2005). Op. cit., 68.

17. ———. (n.d.). About the AFM. Accessed November 14, 2009 at http://www.ifta-online.org/afm/about.asp.

18. ———. (July 2006). Show review. One on one. Accessed April 9, 2009, at http://www.oto-online.com.

19. Hill, K. (June 8, 2007). CRM breaks into show business. E-Commerce Times. Accessed April 20, 2009, at http://www.ecommercetimes.com/story/57743.html?wlc=1244659308.

20. Epstein, Edward Jay. (n.d.). 2004 Worldwide TV Licensing Revenue For Studios. 2004 MPA Consol-idated Television Sales Report. Accessed November 14, 2009 at http://www.edwardjayepstein.com/TVnumbers.htm.