10. Building Research Programs

How do you build a successful constructive design program? The one thing needed is an open theory. All successful programs build on what philosophers call post-Cartesian philosophy, or the social theory consistent with it. These are open frameworks that give priority to design, and theory’s role is to help make sense of why something works or does not work. Another thing needed is patience: it is easy to kill a program too early by demanding results before seeing whether it gains a following. A third thing needed is designers and researchers, as well as people with theoretical and philosophical skills who bring continuity to research over apparently different topics and areas. One thing to avoid is jumping on the bandwagon of issues like service design that come and go; research programs need to be more robust. Another thing to avoid is a focus on methodology. Good research is about content, not about process. This book has shown that constructive design research can carve out a place in second modernity. At best, it creates a rich discourse around design, a discourse that helps designers and researchers to be more confident about the context of their work.

It is impossible to describe everything in constructive design research today, and we need more specific language to understand what is happening in this discipline. For us, this language has been methodology, which gives a simple enough yet informative storyline. As always in methodology, there is a fine line between aim, description, and prescription, which we wanted to avoid. We hope this book is not read as a manual. Having said this, this chapter gives a few tips for establishing and maintaining constructive design research programs.

We have located the origins of research from what Andrea Branzi called “second modernity.”1 In first modernity, design had few industries in which to work, consumer tastes were fairly homogeneous, and taste elites promoted sleek modernism in design. In second modernity, these certainties are not self-evident. Revolutions of taste have moved design from its modernist roots, and design has become a mass profession. 2 Also, the social base of design is far more diverse than before, and this gives design a better ability to respond to demands coming from all walks of life, however surprising these might be.

1Branzi (1988) and Branzi (2006).

We have also seen how constructive design researchers have moved from product design to systems, services, organizations, technologies, and even the relationship of the city to the countryside. 3 Constructive design researchers may have changed the world only a little, but they have certainly seen what is happening around them and taken a stance. Society has changed, and so has design research. It does not have a simple objective anymore.

3For services, see Yoo et al. (2010), Mattelmäki et al. (2010), and Meroni and Sangiorgi (2011). For the garbage collecting case, see Halse et al. (2010); for community health see A. Júdice (2011) and M. Júdice (2011) and the relationship of the city to its surroundings in Meroni and Sangiorgi (2011).

Almost a century ago, László Moholy-Nagy wrote about the need to bring many types of knowledge into design. In the same spirit, constructive design research has opened design for many new developments.

Human history is much too short to compete with nature’s richness in creating functional forms. Nevertheless, the ingenuity of man has brought forth excellent results in every period of hishistory when he understood the scientific, technological, esthetic, and other requirements. This means that the statement, “form follows function,” has to be supplemented; that is, form also follows — or at least it should follow — existing scientific, technical and artistic developments, including sociology and economy.4

4Moholy-Nagy (1947) in Vision in Motion. We have avoided talking about “form” in this book for a reason, but since Moholy-Nagy’s quote has a reference to Louis Sullivan’s famous adage “form follows function,” we need to add a note here.For us, it is not obvious that form is the main concern of design, and is far less a concern to design research: there are other concerns that are equally and more important. In Sullivan’s cliché, “form” is also too easy to understand as information instead of chaos, whether the form is a thing, pattern, model, or service. Finally, it is already a cliché, and there is an industry of variations including titles such as Less Is More, Less+More, Yes Is More, and so forth.Another word we have tried to avoid has been “complexity.” It simplifies history into a process of increasing complexity and tends to lead to an idea that design needs to respond to increasing complexity by becoming more complex. Quite simply, this is not the way in which most designers prefer to work. Just as often, they describe their work using open-ended artistic terms like “intuition” and “inspiration.” Given the well-known shortcomings of the design methods movement, this is understandable.

Several people in this book are not designers by training. They have brought new skills, practices, and ideas into design and design research. It is hard to imagine the constant stream of innovative work coming from Eindhoven without Kees Overbeeke, a mathematical psychologist by training. Similarly, the psychologist Bill Gaver’s contribution to interaction design and its research is undeniable. Many other characters in our story, however, are designers like Tom Djajadiningrat and Ianus Keller in the Netherlands, Simo Säde in Finland, and Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby in England. Yet in other cases, we have been writing about designers whose roots are outside design, like Tobie Kerridge, whose first academic home was in English language, and Johan Redström, whose academic home was in music and philosophy. Research programs are rich creatures in which many kinds of expertise may be relevant.

10.1. Beyond Rationalism

If there ever was a paradigm in design research, it was during the 1960s. At that time, rationalism reigned in various forms. Herbert Simon tried to turn design into a science through systems theory. 5 For writers in the design methods movement, the aim was to turn design into a systematic discipline by making the design process methodic. 6 This was the dominant understanding of design methods in industrial design for a few years. Even though these writers aimed at rationalizing design and not research, many design researchers still built on their work.

This rationalistic ethos was paradigmatic. Its premise was accepted without asking if it was right or wrong. There was no need to question any premise in the post-war university, because it was dominated by one generation of white males with a background in engineering and the military, and with a small number of teachers coming from another generation. Practically everyone had similar values, and it was the Zeitgeist. Systems theory was growing in stature in the natural and social sciences, giving an air of legitimacy to the effort. 7

7See Forlizzi (forthcoming). References to “paradigms” in this chapter are from Thomas Kuhn’s (1962) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.

However, this paradigmatic phase was short-lived. As we have seen, its main proponents quickly turned away from it8 as well as practicing designers who found this effort impractical and unnecessary. Also, this paradigm failed in Ulm, as its long-term headmaster Tomás Maldonado noted (Figure 10.1). 9

8For example, Alexander (1971) and Jones (1991).

9See Chapter 2.

During this time the intellectual climate changed. The rationalistic worldview was discarded in the humanities and the social sciences, at first for political reasons. 10 Some of the criticisms focused on its destructive force; it had created prosperity on an unprecedented scale, but also massive destruction, and others found problems with its conceptual and theoretical underpinnings. 11 When women, lower-middle class students, and new ethnic groups entered universities, the social basis of the rational paradigm was contested. For these critiques, rationalism was little more than a hollow claim to universalism by one demographic group.

10Marxism was important in European design schools, but as few schools did research in the 1970s, its impact on research was minor. In information systems design, the early 1980s saw several Marxist developments, in particular, in Scandinavia (see Lyytinen, 1982 and Lyytinen, 1983; Ehn, 1988a). The detailed history of Marxism in Western design is still unwritten.

11These critiques were already voiced in Ulm in the 1960s (see the next note), and in the 1970s and 1980s software designers joined the chorus (see Dreyfus 1972, 1993; Winograd and Flores, 1987; Ehn, 1988a and Ehn, 1988b).

As soon as we look at constructive design research programs, we find ourselves in a room familiar to any well-read philosopher, humanist, artist, or social scientist. From this room, we find J.J. Gibson’s ecological psychology, which in turn builds on Gestalt psychology and is tied to phenomenology from many different directions. Similarly, there are references to symbolic interactionism and surrealism, and through them, to the very foundations of twentieth century thinking. These foundations include psychoanalysis, structuralism, phenomenology, and pragmatism.

Philosophers call these intellectual and artistic movements post-Cartesian. This word covers many things, such as the major differences between, say, phenomenology, structuralism, Dada, or Gestalt psychology. 12 Post-Cartesian philosophies importantly tell designers to approach the world with sensitivity by trying to understand it rather than by imposing theoretical order on it. They tell designers to become interpreters rather than legislators, and to use the metaphor of Zygmunt Bauman, a leading Polish-British social critic. 13 This quality is particularly important in design — a creative exercise by definition.

12For example, see Aicher (2009) and Hoffman-Axthelm (2009, pp. 219–220) for accounts of the theoretical basis of design at the Ulm school.

10.2. Contribution and Knowledge

Constructive design research creates many kinds of knowledge, and designs capture knowledge from previous research. When researchers study these designs, they generate knowledge about design techniques and processes, as well as about how people understood and appropriated these designs.

Typically, however, the most important form of knowledge are the frameworks researchers build to explicate their designs. These frameworks vary from Stephan Wensveen’s interaction frogger and Katja Battarbee’s co-experience to Jodi Forlizzi’s product ecology. 14 Even the frameworks may sometimes be unimportant: a good deal of critical design does not try to develop frameworks. Its contribution lies in debates raised by its designs. Constructive design research produces ways to understand how people interact with the material world. It also shows how to use that knowledge in design.

Constructive design researchers routinely build on theoretical and philosophical sources from older, more established fields of research, but few claim to contribute to psychology, sociology, philosophy, or the natural sciences. Knowing the theoretical background of a program helps to keep a program consistent and may help to take it forward at important junctions, but it does not help to make a better television, communication concept, or mouse. 15 Typically, only very experienced researchers go to philosophical heights. Even they take this step cautiously when settling controversies or breaking free from clichés of thought and not with the intention of contributing to philosophical discourse.

15See Carroll and Kellogg (1989).

The word “knowledge” easily leads to unnecessary discussions that hinder research. 16 Chemists, after all, do not think they need to know how chemists think in order to do research or what kind of knowledge they produce. We believe that here, design needs to learn from the natural and the social sciences. It is better to go full steam ahead rather than stop thinking about knowledge in the abstract. When the volume of research grows, there will be milestones every researcher knows, refers to, and criticizes. Sociology may not have found any hard facts about society, but there is a tremendous amount of wisdom about society in that discipline.

16Lawson (1980) and Lawson (2004), Cross (2007) and Visser (2006). For an extensive discussion of knowledge in design, see Downton (2005).

Constructive design research probes an imagined world, not the real world of a social scientist. Although things that are often playful and sometimes disturbing populate it, it is a very useful world. It makes it possible to study things outside normal experience. For example, we learn how rich interaction might work by reading Joep Frens’ work and how social media based on “self” might work by reading John Zimmerman’s studies. Their research tells a tremendous amount about specifics like materials, forms, functions, user experience, software, and the social environment of design. 17 This knowledge is useful for the project at hand, and it may also end up being used in industry (Figure 10.2).

17In some cases, there are several environments, as our discussion of Nowotny et al. (2008) implies.

One implication is important. The “contribution” in constructive design research is not like in the natural sciences, where it is possible talk about “facts” as long as one remembers that most facts are contestable. 18

18See Latour (1987). There was a long and once heated discussion in sociology about knowledge and whether even mathematical facts are social or not. In some sense, they are, because there would be no mathematics without people who agree to work with some conventions. Still, some conventions stay long enough to be treated as practically eternal facts. This happens in mathematics and logic, but also in some of the exact natural sciences.

With the possible exception of some researchers in Lab, most constructive design researchers work like the humanists and interpretive social scientists. They usually want to improve thinking and understanding, not to make discoveries, much like the humanities and the social sciences, where a new perspective or distinction can be an important contribution. Practically all contributions to knowledge of Shakespeare or Goethe come from improvements in discourse. This, however, is not a dramatic distinction. In the sciences, better explanations are welcomed even when little new data exist. Also, the main contribution of many scientific projects is an approach, method, or instrument. There is no one right way to do “science”; for example, to study bird migrations, researchers need different methods from astrophysics.

10.3. How to Build Research Programs

To anyone interested in entering constructive design research, the main advice from this book is to think in terms of programs. If we look at places in which constructive design research has taken shape, we see variety, but also many connecting dots. The key element is a community that is able to work with things we have talked about, including theory, many types of research methods, and imaginative design skills. Programs also need some infrastructure to make construction possible. What kinds of machinery and workshops are needed remains unanswered in this book, but for us it is clear that any design school, medium-sized design firm, and global corporation have everything necessary.

In design schools, the main difficulty is understanding how research works. Programs evolve and mature over time. What is important is typically seen only in retrospect and often years after the fact. 19 Few designers have enough patience to wait that long for results. It is easy to kill programs before they lead to success. In technical environments, the most difficult question is how to give enough space to design. As Kees Overbeeke noted in his inaugural lecture in 2007 at Technische Universiteit Eindhoven, universities tend to put too much value on cognitive skills at the expense of other human skills. 20 If the notions of science are narrow-minded, design may not get a fair chance to show its value (Figure 10.3).

19Here we obviously follow Lakatos. See Chapter 3.

20Overbeeke (2007). We must add that he specifically blamed the Greeks (the ancients, to clarify) for this cognitive bias and overvaluation of the written word over the bodily skills.

Writing a successful program in a committee would require oracle-like abilities. Even though writing successful programs may be difficult, it is not difficult to create preconditions and make a good attempt. The risk is small if we look at the research described in this book. Major contributions often come from small groups, and these groups need to have theoretically knowledgeable senior researchers, young researchers, and designers, but they do not need dozens of people. 21

21For good reasons. Large organizations get bureaucratic. They also increase the stakes so much that too many stakeholders get interested in protecting their investments and taking the credit for results.

Compared to these questions of ethos and managerial culture, some things are plain in comparison. In supervising research, it is important to build research on what others have done in the program. This is obvious for people in science universities, but clashes with the ethos of creativity that reigns in design schools, where originality and raising personalities are stressed. Also, research programs are not run by organizations. Every successful program has been open to change and has given things to other programs. For example, field researchers in Helsinki borrowed from cultural probes and from the Interactive Institute’s artistic work. Larger organizations may run several programs, as in Sheffield-Hallam University in England.

Yet another observation is that it makes sense to build on one’s strengths, whether design, science, social science, or contemporary art. 22 In places like Helsinki, one can work with complex technology, design, consumer goods, Web systems, and services simultaneously. All resources required are within a reasonable travel distance. With Philips Design nearby, it is natural for researchers in Eindhoven to focus on sophisticated interactive technology with a serious focus on process. London’s art market accepts complex artistic argumentation that would raise eyebrows in Pittsburgh with its pragmatic culture valuing solid engineering.

22See Molotch (1996).

However, this argument should not be stretched too far. It would be plainly wrong to say that the environment somehow dictates what researchers can do. Such a claim runs contrary to what we have just said about the relatively modest resources needed for a solid research program. Also, sometimes limits turn into opportunities; revolutions in thinking often come from surprising places. Why not art in Pittsburgh, which has some of the best art collections imaginable, but not the elite tastes of a New York or a Paris dictating what is interesting?

10.4. Inspirations and Programs

Our list of things that inspire constructive design researchers includes issues, ordinary things in society, research-related sources, and tinkering with materials.

Issues are funded by major corporations and the governments. The biggest issue lately has no doubt been climate and sustainability, but many other things on the design research agenda are also issues. Some issues come from technology policy and technology companies, as the steady stream of new technologies since the 1980s reveals. For example, one of the buzzwords of 2009–2010 was “service design,” which initially had its origins in IBM’s global strategy. It was later pushed into research and higher education as a novelty with little regard for the fact that most advanced economies have been service economics since the 1960s. Issues come and go. New issues emerge when governments and administrations change.

Behind these issues are the humbler sources in everyday life. These consist of ordinary activities, technologies, things happening on the markets, and all kinds of sources in culture, such as folklore, books, ads, and films. 23 Herein lies the charm of second modernity: it is manifold, consisting of many overlapping realities that inspire endlessly. Things closer to design research are scientific theories, frameworks, data collected in other studies, and the very history of design. Even closer to design is tinkering — work on structures and materials in workshops and laboratories. Interaction designers tinker with software rather than with materials and physical objects. 24

23Think about the film noir metaphor behind Dunne and Raby’s Design Noir.

As this offhand list shows, inspiration can come from anywhere. It is more important to look at how researchers turn these ideas into research questions and studies.

Here again, we meet research programs. Researchers turn what they see into research problems through conceptual analysis and theoretical work. In this work, they turn to their own program, look at what other researchers have done, and then decide what to do. The exact order in which these things are done varies and is less important than situating research into a program. Research programs have many ways to build on inspiration. Some stress artistic sources, while others turn to design history. Some turn to theory in psychology and sociology, while others start with user studies. 25

25Presence Project (2001); Intel (2010b).

Although sources of inspiration may change, programs have their histories, key members, methodological preferences, and tradition. These things give them identity but also an air of calmness. What may seem like rigidity is really a source of flexibility. Programs may change slowly, but they are repositories of expertise. Over time, successful programs provide referents and precedents. 26 For this reason, they are able to work on a wealth of inspirations. Thus, critical designers had no difficulties in going into the sciences, researchers in Helsinki switched from smart products to services and urban design effortlessly, and Danish researchers went from participatory design to co-design without missing a beat.

26See Goldschmidt (1998) and Lawson (2004). As Pallasmaa (2009, p. 146) noted, good architects collaborate not only with builders and engineers, but with the whole tradition of architecture: “Meaningful buildings arise from tradition and they constitute and continue a tradition…. The great gift of tradition is that we can choose our collaborators; we can collaborate with Brunelleschi and Michelangelo if we are wise enough to do so.” No doubt, this statement has more than a hint of exaggeration, but the basic point is right and is also important for designers.

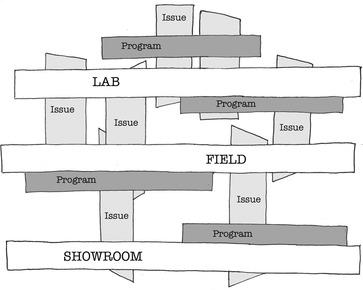

10.5. Research Programs and Methodologies

The first exemplary constructive pieces were done between 1998 and 2005. As often, the best formulations of central ideas are the first articulations. Some kinds of progress, however, are built into the notion of the research program. Where is research heading next? (See Figure 10.4.)

|

| Figure 10.4 |

One thing to note is the difference between research programs and methodologies. Without a doubt, as constructive design research matures, several new research programs will emerge. They will find homes at art and design universities, technical universities, and in design practice.

Another thing of note is the difference between methods and methodologies. We will see new methods in the future. In inventing new methods, there is basically no limit, especially if we look at what Carnegie Mellon’s Bruce Hanington once called “innovative methods.”27 We believe that the more methods there are, the better. Novelty in constructive design research has often been based on new methods rather than technologies, issues, or theories. There is far less room for methodological innovation. Here, constructive design research is in good company. The range of methodologies in the sciences is far smaller than the range of methods.

27Hanington (2003), Stappers and Sanders (2003). For an empathic interpretation of some of these methods, see Koskinen et al. (2003).

There are some directions to watch to foresee the future of constructive design research. There is a small step from some contemporary art and craft practices to research, and there are already good examples of turning craft into research. 28 Another likely breeding ground is engineering. This is well illustrated by places like the MIT Media Lab.

28For art, see Scrivener (2000). For craft, see Mäkelä (2003) and Niedderer (2004). Craft Research Journal started in 2010. Also, the first Craft Reader appeared in 2010 (Adamson, 2010).

Also, social issues like climate change may be around long enough to feed research programs that bring more science into design research. In several universities, there are scientists who have become designers but who build their research programs on their scientific training. For example, there is only a short step from Carlo Vezzoli’s work on sustainable design in Milan to constructive design research. In the near future, we will most certainly see constructive work based on his work. 29 Indeed, it is easy to imagine a chemist using her skills in design rather than doing technical or industrial applications.

29See Manzini and Vezzoli (2002) and Vezzoli (2003).

There are also seeds of the future growing within existing research programs. With the exception of Lab, there has been little use of statistics in constructive design research, but there are several interesting openings. For example, Oscar Tomico combined statistics with George Kelly’s personal construct theory to create a tool for capturing the sensory qualities of objects for design. 30 Similarly, Kansei engineers analyzed emotions and senses with multivariate statistics. Although the community has mostly influenced Japanese industry and technical universities, it has gained some following in Europe. 31 Furthermore, some recent work in Eindhoven has built on philosopher Charles Lenay’s phenomenological work on sensory perception, combining sophisticated experimental work and statistical decision making to this ultimately descriptive philosophy. 32 Although phenomenology and symbolic interactionism are usually seen as qualitative traditions, this is a miscomprehension. There will no doubt be successful attempts to bring statistical analysis into design, and mixed methods approaches are certainly in the near future. 33

31See, for example, Lévy and Toshimasa (2009).

33Social scientists talk about “triangulation” when a study uses several methods simultaneously. The idea is that one can trust the results better when several methods point to the same results or interpretation. The origins of the word are in cartography and land surveying.

One interesting trend is happening in Field. In Italy and Scandinavia, user-centered design has evolved into co-design and action research. 34 A step to organizational development and community design is not far, but this will further distance design from its base in products. 35 Another possible step is to study the business models in practice, which is happening in the SPIRE group in Sønderborg, Denmark, under Jacob Buur’s stewardship. Here design research is intertwined in the policy sciences of the 1960s, but hopefully it avoids becoming overtly political and entangled in value discussions.

Finally, researchers need eclectic approaches to tackle “truly wicked problems” that require years of concentrated work with many stakeholders who often have contradictory agendas. Solutions to problems like climate change have to be particularly imaginative. Any solution has to survive the debate on a large and competitive “agora,” where the audience consists of scientists, politicians, companies, and the general public. 36 There are several ways in which constructive design researchers are tackling these truly wicked problems, but are they satisfactory?37

37For example, see Beaver et al. (2009), Switch!, and the work of the Júdices in Vila Rosário, mentioned in Chapter 5.

10.6. The Quest for a Big Context

When Andrea Branzi was talking about second modernity, he put his finger on something every design researcher knows even though design researchers may not have the vocabulary to talk about it. Second modernity opens many kinds of opportunities for those designers who are willing to seize them. 38 They may be weak and diffuse rather than based on the sturdy realities of the past. For that reason, second modernity is difficult to grasp with concepts coming from first modernity. This applies to design research as well as to design.

38Branzi (1988) and Branzi (2006).

Second modernity requires not only intellectual openness and curiosity but also modesty. We have seen how constructive design researchers have deliberately built on frameworks that encourage exploration. This echoes the opinions of some of the leading design practitioners. In an interview with C. Thomas Mitchell, Daniel Weil reflected on his experiences when studying at the Royal College of Art (RCA) in London in the early 1980s. He talked about how he was disappointed in designers’ discourse and was attracted to contemporary art.

When Weil was talking to Mitchell, he had already left his professorship at RCA and was working at Pentagram. He wanted to gain a better grasp of “the big context”: not just a product but also things around the product. He was worried about how industrial design in his day focused on products without context.

But there’s nothing in three dimensions like that, no understanding of the big context, which is what architecture traditionally did. I believe that is the role of industrial design. The people who work in three dimensions need to move away from just being a service and understand the bigger picture. So it’s all about understanding the context instead of just purely designing a solution according to what has been designed before in a similar area…. What has happened is that designers are accustomed to the one-to-one scale, but when it starts to go large, they’re a bit lost. So it’s quite important to work more conceptually on bigger pictures. Then they will find it a lot easier to discover more complexity in what they’re doing. It’s important that we put more complexity and a bit more intellect into the activity of designing, and the activity of encouraging other designers by doing so.39

39Weil (1996, p. 25).

We see a revolution brewing here. Weil was among those young designers who grew up with Branzi’s Studio Alchymia and was soon invited to participate in Memphis by Ettore Sottsass, Jr. The period he describes prepared him for new kinds of questions. Indeed, why does the radio have to be a box?

This quest for a bigger context later became the breeding ground for Showroom. It, however, can be observed elsewhere in constructive design research. For example, ergonomics taught how humans interact with their physical environment, interaction designers brought systems thinking to design from computer science, and design management introduced them to formal organizations and management, to take only three of the many examples available (Figure 10.5). 40

40The question of whether designers should be professional problem-solvers or do design in a broader context is one of the standing debates in design. Maldonado contrasted Ulm with Chicago’s New Bauhaus:For Maldonado, this was a call to reform Ulm’s education to train designers who think about social content rather than think opportunistically about the market. His designers were to enrich cultural experience in addition to satisfy concrete needs in everyday life.

The HfG that we are setting up at Ulm proposes a redefinition of the terms of the new culture. It will not be content to simply turn out men that know how to create and express themselves — as was the case with Moholy-Nagy in Chicago. The Ulm school intends to indicate the path to be followed to reach the highest level of creativity. But, equally and at the same time, it intends to indicate what should be the social aim of this creativity; in other words, which forms deserve to be created and which not. (Maldonado, quoted byBistolfi, 1984, second page)

Weil’s generation, however, was looking for new vocabularies from design. His vocabulary of choice was design management, which gave him an opportunity to design in a strategic context. When constructive design research was created, it picked up many of the leads left by these designers but turned to research. In about ten years, constructive design researchers have given design ways to talk about issues, such as direct perception, social and cultural context, and the implications of top-notch science. 41 Design needs new vocabularies to work with the big context. The unique contribution of constructive design research is that it creates these vocabularies in a design-specific, yet theoretically sophisticated manner.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.