3. Research Programs

What makes constructive research successful? A good deal of the answer lies in the fact that it is programmatic. Researchers build on previous work and raise new questions; successful programs are able to generate new research questions. While they maintain their inner core, they are able to respond to many types of themes emerging from technology and society. These programs are, in the words of the scholar of science Helga Nowotny, socially robust, exploring social implications of technology rather than trying to create applications or just producing knowledge. Constructive design research is a science of imagination: it imagines possible futures and constructs them in order to study them in detail. Successful programs create alternative ways of seeing technology and society and inform us about better futures.

A philosopher of science, Imre Lakatos, once argued that progress in research ultimately lies in research programs rather than individual studies. 1 Progress happens when some piece of research adds new knowledge to or corrects a research program. A successful research program generates new content and new problems in the long run. Any successful research program also has a negative and a positive heuristic. A negative heuristic consists of a “hard core” of beliefs that is not questioned, and a protective belt of auxiliary hypotheses that can be subjected to debate and can be wrong. A positive heuristic tells which questions and objections are important and in what order they are tackled when they show up (see Figure 3.1). 2

2.We are not the first ones who have introduced Lakatos to design research. See also Glanville (1999) van der Lugt and Stappers (2006). Binder and Redström (2006) used the term in an architectural sense. Peter Downton proposed to rate programs in terms of how much danger to existing thinking its core idea posed. At the extremes are ideas that are capable of affecting personal practice and ideas that have power to invert existing knowledge. However, as Downton noted, it is too much to expect too much: most research programs “only contain small dangers” (Downton, 2005, p. 9).

|

| Figure 3.1 Research runs in programs and has a past: research programs enable imaginative dialogs with the past3 3.As Juhani Pallasmaa notes, “the great gift of tradition is that we can choose our collaborators; we can collaborate with Brunelleschi and Michelangelo if we are wise enough to do so” (Pallasmaa 2009, p. 146). |

Lakatos’ concept gives us a good understanding of how constructive design research works. For example, we see how it consists of various activities. Some work focuses on theory, some on methods, and some on methodology, whereas the main body of work typically consists of constructive studies, reported in journals, conferences, and exhibitions. Also, we see how people take different roles in research.

3.1. Some Features of Constructive Research Programs

By now, there are several successful research programs in constructive design research. Interaction design in Eindhoven is certainly programmatic, and critical design in London has generated excess content over the years. Empathic design, co-design, and action research in Scandinavia have been programmatic, as have service design and design for sustainability in Milan. Research on user experience in Carnegie Mellon also belongs to this group.

In theoretical terms, the most influential work came from the Netherlands and from Pittsburgh. In this work, conceptual and theoretical development took several routes. In Delft, researchers first built on J.J. Gibson’s ecological psychology, but soon they turned toward design issues like pleasure and emotions. A few years later, research focus in the Netherlands shifted to Eindhoven, where researchers were increasingly interested in emotions and experience. So far, these researchers have created several frameworks for designing interactive technology. 4 On the other side of the Atlantic at Carnegie Mellon, user experience became the new cornerstone, followed by an interest in social ecology and the concept of self. 5

5.Forlizzi and Ford (2000), Battarbee (2004). For social ecology, see Forlizzi (2007). For designing for self, see Zimmerman et al. (2009).

Initially these programs created little new theory. Instead, emerging interaction design borrowed theory from more established fields and researchers like the cognitive and ecological psychologist Don Norman. 6 However, recent work in places like the Netherlands and Carnegie Mellon University has clearly gone beyond cognitive psychology. Researchers are currently interested in issues like identity and how people function in the world with their bodies. 7 Constructive design research is gaining a theoretical core.

6.In historical contexts, interaction design has to be used cautiously. IDEO’s Bill Moggridge (2006) claimed to have invented the term “interaction design” and, historical research pending, may be right. Along with IDEO, he certainly made it popular. For important textbooks on interaction design, see Schneiderman (1998), Preece (1990) and Sharp and Preece (2007).

Some programs are also gaining a “hard core” of non-debatable beliefs—for example, the fate of “cultural probes” (see Chapter 6). Their main ideologist was Bill Gaver, a former cognitive scientist, who rejected scientific methodology and built an artistic methodology to replace it. His main inspiration was situationist “psychogeography,” which urged artists to construct situations that would lead people to notice how their unthought-of routines restrict their lives. 8

8.Gaver et al. (1999), Presence Project (2000), Debord (2002). As Jappe (1999, p. 4) noted, the situationist notion of “spectacle” is indebted to commodity fetishism, as Karl Marx called the confusion of exchange value of a product with its value in use.

However, with few exceptions, designers and human–computer interaction (HCI) researchers who used the probes overlooked this artistic background and turned the probes into a data collection technique akin to diary studies. In 2008, Kirstin Boehner and her colleagues defended the original intentions of the approach against these “misuses.”9 They noted that cultural probes originally aimed to subvert or undermine traditional HCI methods, not supplement them. For them, the hard core of the probes lies in what they call the hermeneutic or interpretive methodology. The room for debate is in the details of probes, not in the basic approach. 10

10.Boehner et al. (2007, pp. 1083–1084. In fact, Boehner et al. used the wrong terminology here. If the probes build on hermeneutic and interpretive thinking, they become humanistic and social science instruments rather than artistic expressions. For a balanced account of how the probes have been used and how tensions exist in the probing community, see Keinonen (2009).

Cultural Probes

Cultural probes have become commonplace in European design research. Originally, they were developed at the Royal College of Art in the second half of the 1990s. A milestone article was published in 1999 by Bill Gaver, Tony Dunne, and Elena Pacenti.

As the name suggests, this method has a metaphoric basis. Quite simply, the idea is to send probes to culture, just as oceanographers send probes to the oceans or scientists send them to outer space. The probes gather samples from wherever they go, and send them back to researchers, whose job is to make sense of them.

A typical “probe” was a package of things like a disposable camera with instructions about what to shoot, postcards with provocative questions, diaries, metaphoric maps, and slightly later, all kinds of technological looking objects. Every package had instructions about how to do the tasks the researchers wanted (like photographing one’s favorite place or the contents of the refrigerator) and about how to send the data back to researchers.

The social sciences have had a long and suspicious history of “diary studies.” Researchers cannot control how and when people fill the diaries, which means that a sociologist or a psychologist does not know how to interpret these data.

Different from diary studies, from the beginning the probes were described as non-scientific instruments that did not collect representative and accurate data. This non-scientific tone extended even further; for example, to make sure that the probes were also interesting to the people who got them, researchers gave them to people personally. Also, the probes were to be projective and reflect the personality of the researcher rather than be a neutral instrument. Furthermore, the probes were built on artistic references. Finally, Gaver and others refused to give instructions about how to analyze the probes while vehemently denying that it is possible to analyze them scientifically since this was not their purpose.

The probes have gone through a long history of misunderstandings and misuses — some intentional, some unintentional. During the past decade, however, this methodology left a long mark on design research: it is playful and designers love its philosophy.

Gaver (1999).

Also, programs have a social organization. They have precursors, followers, and critics. When looking at empathic design in Helsinki, the precursors came from places like Palo Alto Research Center, the contextual inquiry of Hugh Beyer and Karen Holtzblatt, participatory design, SonicRim, IDEO, and Jodi Forlizzi’s work on user experience. 11 However, theoretical work quickly took philosophical and sociological tones. Books like Empathic Design articulated the interpretive foundations of this work, but empathic design also built on pragmatist and ethnomethodological references. 12 Research methods were borrowed from other researchers and practice, but were used creatively. For instance, Tuuli Mattelmäki recast the cultural probes in interpretive terms. 13 Key case studies were done in several projects, including Väinö, which focused on senior citizens, and Morphome, which focused on proactive information technology. This work has influenced research in Scandinavia and in Delft, Carnegie Mellon, and Milan. 14

13.Mattelmäki (2006).

3.2. Imagination as a Step to Preferred Situations

When Herbert Simon famously defined design as an activity that tries to turn existing situations to preferred ones, he pointed out a crucial feature of design — it is future-oriented. Designers are people who are paid to produce visions of better futures and make those futures happen.

However, although constructive researchers share Simon’s general aim of improving the future, the way in which they work is different from what he proposed. Writing in the science-optimistic and technocratic post-world America, he was able to build on a very particular version of science. This is hardly viable in recent, more skeptical times in which research is tied to society in far more ways than during the era of Big Science. As the failure of the design methods movement suggests, design and design research will fail if they are reduced to a formula.

Constructive design researchers do not try to analyze the material world as Simon suggested, nor do they see design as an exercise in rational problem solving. Rather, they imagine new realities and build them to see whether they work. The main criterion for successful work is whether it is imaginative in design terms. Theirs is a science of the imaginary (see Figure 3.2).

For designers, imagination is methodic work rather than a mental activity. They do not produce those futures by themselves, but as a part of a larger community of practitioners ranging from engineers to many types of professionals and other actors. This work takes place in a cycle that begins with an objective of some kind, and continues to user studies. These studies lead to concept creation and building mock-ups and prototypes that are typically evaluated before the cycle begins again. 15

15.For example, see Szymanski and Whalen (2011, p. 12).

There is also another way in which imagination characterizes constructive design research. The things produced by researchers are seldom produced. Making them into commercial products would require the resources of major international corporations, which is clearly beyond most researchers’ powers. 16 Evaluating constructive design research by whether it leads to products is unfair, especially when researchers are faced with “wicked” issues that can hardly be solved by anyone.

16.See in particular Joep Frens’s thoughts about prototyping in research in Chapter 4.

3.3. Making Imagination Tangible: Workshops and Studios in Research

Another design-specific characteristic of constructive design research is that it builds things, which is reflected in its infrastructure. Typically, this infrastructure consists of comfortable studio-like places that house discussions and create concepts and goes all the way to workshops with heavy machinery as well as computer and electronics labs.

In these places, ideas are made tangible, first with cheap materials like scrap wood, scrap metal, or foam, or in the case of software, programs in some test environment. Just as in any sandbox, iteration goes on until something survives critique. In this work, analysis and reasoning are important, but equally important is design experience, whether it is based on emotions, feelings, or intuition. 17 This work may start from theories, methods, and fieldwork findings, and just as often it begins with playing with materials, technology, and design precedents.

17.Stappers (2007; see also Chapter 4). There is a lot of sandbox culture in science too. Again, Herbert Simon provides an example. After learning elementary programming and meeting Allan Newell in 1952, Simon and Newell decided to build programs that could play chess and construct geometrical proofs. They worked on what became the Logic Theorist, which was able to construct proofs from Russell and Whitehead’s Principia Mathematics in 1955–1956, first in a sort of simulated computer, then in RAND Corporation’s computers. Simon’s excitement in finding an environment in which he could test his mathematical theories of human action is easy to sense from Hunter Crowther-Heyck’s biography (2005, pp. 217–232).

Over time, this culture creates a stockpile of concepts, designs, technologies, platforms, and stories that carry the culture and give it a distinctive flair. Without this culture of doing, many things of interest to designers would go unnoticed. 18 What would specifically be lost are those visual, material, and cultural and historical sensitivities Sharon Poggenpohl sees as essential to design. 19 Designers have to worry about things like how some material feels, how some angle flows gracefully over an edge, or how interaction works.

18.In this section, we are influenced by Julian Orr’s (1996) work on the work culture of copy machine repair men.

19.Poggenpohl (2009a, p. 7). See also Chapter 1.

In an extreme form, this kind of culture has existed in places like the MIT Media Lab. In its hacker culture, doing has always been more important than reflection. This culture aims at pushing technologies to the extreme and finding ways to do things previously regarded to be impossible. However, the culture comes under various names such as innovation in Stanford’s “d.school,” the quality in interaction in Technische Universiteit Eindhoven, or simply education and teaching design skills in places like IO Studiolab at Technical University of Delft and Aalto University’s Department of Design. 20

20.For how the sandbox culture is integrated into research through teaching at TU/Eindhoven, see Overbeeke et al. (2006).

Sometimes the culture is not bound to one place but to a regional network, as in Lombardy, where designers have explored design possibilities with industry through prototypes, one-offs, and limited editions. 21 Invariably, there is a “community of practitioners” with a variety of skills in doing, critique, and theory that keep the culture going (Figure 3.3). 22

21.See Branzi’s (2009) Serie Fuori Serie exhibition catalog from Triennale di Milano and Lovell (2009).

22.The notion of community of practice is from Brown and Duguig (2000).

|

| Figure 3.3 Downward: three pictures of studios; four of material-based workshops; three shops with industrial machinery. (Pictures from Helsinki, Bengaluuru, Borås, Pasadena, and Delft.) |

Workshops and studios are necessary, but are not the right condition for a healthy constructive design research program. A program may be successful for a few years if it hits the right technological or political gold mine. However, when returns from this mine get leaner, this model faces difficulties. For example, during research on tangible interaction the MIT Media Lab was followed globally, but now this following is far less extensive. Although researchers continue producing interesting prototypes, the Media Lab produces new thinking at a far slower pace.

3.4. How Constructive Design Research Produces Meaning

That constructive design research is grounded in imagination is also reflected in how researchers understand their contribution. Andrea Branzi wrote that the task of design research is to keep distance from the “pure practice of building.”23 For him, design in second modernity should offer alternatives rather than try to alter reality directly. No doubt, most constructive design researchers agreed with him when he wrote:

23.Branzi (2006, p. 16).

The architectural or design project today is no longer an act intended to alter reality, pushing it in the direction of order and logic. Instead the project is an act of invention that creates something to be added on to existing reality, increasing its depth and multiplying the number of choices available.24

24.Branzi (1988, p. 17).

Here designers can learn from architecture. As Peter Hall notes following Cranbrook’s Scott Klinker, architecture has a rich body of discourse based on hypothetical designs. 25 This is also the case with design, even though hypothetical products tend to play a less prominent role in it than in architecture, where most plans are never realized. 26 Plainly, if hypothetical designs are successful, they may change the ways in which people think about material and social reality. They can open up possibilities and prepare action.

25.Hall (2007). As innovation-focused schools, he classified IIT in Chicago and Stanford, while in the humanities camp he placed Philadelphia and Parsons after Jamer Hunt. On the art school route are the Royal College of Art in London and Cranbrook Academy of Art, which “have reputations for critical thinking and producing sexy imagery of objects — often more hypothetical than manufacturable,” as Hall noted in his essay.However, some of the greatest revolutions in design have come from people like Ettore Sottsass, who described himself in a Museo Alessi interview in 2007 as a “theoretical designer; just as there are theoretical physicists who … don’t make plans for getting to the moon [but] think about what sort of physical laws a person going to the moon may encounter.” This is just a metaphor, but there is a point in it. Many followed Sottsass; in effect, he became a theorist of design (see Museo Alessi design interviews, Sottsass, 2007, p. 24).

26.Dunne and Raby (2001, p. 59).

Having a discourse based on hypothetical designs has several consequences: it enriches imagination and opens new ways of seeing and discussing opportunities. 27 It also provides exemplars and precedents that may be useful when new problems and opportunities emerge. This discourse may sound like art, but it may also provide important preparation for the future, much as a play prepares children for their later years.

27.Molotch (2003). Andrew Abbott, a leading sociologist of professions, noted that there are professions like the military whose work almost totally consists of such hypothetical discourses (Abbott, 1988). Scenarios prepare for possible action.

Design has many types of hypothetical discourses, many of which have commercial roots. As Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby wrote:

Critical design, or design that asks carefully crafted questions and makes us think, is just as difficult and just as important as design that solves problems or finds answers. Being provocative and challenging might seem like an obvious role for art, but art is far too removed from the world of mass consumption … to be effective…. There is a place for a form of design that pushes the cultural and aesthetic potential and role of electronic products and services to its limits…. Critical design is related to haute couture, concept cars, design propaganda, and visions of the future, but its purpose is not to present the dream of industry, attract new business, anticipate new trends or test the market. Its purpose is to stimulate discussion and debate amongst designers, industry, and the public.28

28.Dunne and Raby (2001, p. 58). This quote is important because it shows many connections to practice. Indeed, quite often the best design ideas never enter the market but remain in the conceptual practices of designers.

Not only critical designers propose alternatives to the present. When Philips hired Stefano Marzano to lead its design team in the mid-1990s, one of his first initiatives was a visionary process called Vision of the Future (Philips Design, 1995). The aim of the project was to re-imagine products rather than create science fiction like new worlds. It was design fiction, based on the idea that it is important not to accept existing economic and technical constraints. The results were a book, a Web page, and a series of traveling exhibitions focusing on themes like the kitchen. The aims of the project were very different from those of Dunne and Raby’s critical design: Vision of the Future and several other projects re-imagined better futures instead of trying to disrupt existing ones. Still, for a company like Philips, this was an exceptional move. Since then, many companies have done projects like these. Perhaps most famous of these is Alessi. 29

29.For Vision of the Future, see Philips Design (1995). For other projects by Philips Design, see Philips bookstore at design.philips.com/about/design/designnews/publications/books/ (Retrieved August 11, 2010). The New Everyday was published not by the company, but by 010, an art and design publisher based in Rotterdam (Aarts and Marzano, 2003).Alessi’s projects have been described by Robert Verganti (2009). Some examples done with design universities are The Workshop (Alessi and UIAH, 1995) and Keittiössä: Taikkilaiset kokkaa Alessille — UIAH Students Cooking for Alessi (Alessi and UIAH, 2002).

Needless to say, there are many ways to construct and understand such alternative discourses (see Figure 3.4). Some of these discourses try to alter and redo existing products such as concept cars, haute couture, or Droog Design. Some discourses take more critical overtones, providing designers not only with a mandate to think differently but also a mandate to think about what deserves to be created and what does not. 30 At the more radical end, such discourses aim at creating utopias. Most designers obviously fall in the middle of this scale. They want to make a difference but are far humbler about their powers than they were in the 1960s. 31

30.The quote about what deserves to be created is taken from the first paper written by Tomás Maldonado after he came to Ulm. This was the how he distinguished Ulm’s education from that of Bauhaus. Bauhaus, he wrote, was “content … to produce people who can create and express themselves,” while “the Ulm school intends to mark out the path to the highest level of creativeness, but at the same time, and to the same extent, to indicate the social aims of this creativeness, i.e., which forms deserve to be” (Höger 2010, p. xvi).

31.For a design-focused analysis of these utopians, see Maldonado (1972, pp. 21–29). For art, see Bourriaud (2002, pp. 45–46), who noted that contemporary art mostly seeks to construct concrete spaces instead of utopias.

From a bird’s eye perspective, these differences are less important than the goal, which is to provide alternatives to deeply ingrained habits of thinking. If we say that since people have certain goods and they use certain technologies then they have to use them in the future as well, we have committed an error in judgment. Following the Cambridge philosopher G.E. Moore, philosophers call this error the “naturalistic fallacy”: inferring from what is to what ought to be. Its consequence can be called the “conservative fallacy”: thinking that what exists today cannot be improved. Wake-up calls are occasionally needed.

3.5. Toward Socially Robust Knowledge

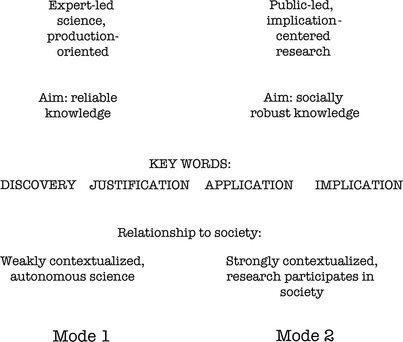

Constructive design researchers are not alone in thinking about knowledge as statements in social discourse. As the sociologists of science Helga Nowotny and James Gibbons have noted, contemporary research is linked to society in many ways and faces many kinds of public and private scrutiny. The key questions most institutions that fund research ask are what kinds of applications research produces and what are its social, economic, and ecological implications. Research has to survive discussions in those boardrooms in which politicians and captains of industry decide where to allocate resources. 32 Many things in research have their origins outside research programs; social forces shape research agendas, priorities, topics, and methods (see Figure 3.5). 33

32.Nowotny et al. (2008) talked about “agoras” rather than marketplaces, stressing the political character of public places like the square where free men of Athens convened to decide the affairs of the city-state.

33.Nowotny et al. (2008, p. 131).

|

| Figure 3.5 |

This is where we need to revisit the notion of the research program. Lakatos was mainly interested in understanding how physics works; however, we need to keep in mind that he wrote in the 1960s. Back then, science was able to maintain a high degree of autonomy because governments, public monopolies, and oligopolistic companies funded it. Scientists worried about making discoveries and reliable explanations rather than about applications or implications, that is, what knowledge does to society. The ideal was to produce unbiased, freely shared knowledge among the community of peers. 34 How scientific knowledge was applied was another story. This was an era of knowledge transfer: what science discovered, society adapted.

34.As a sociologist of science, Robert K. Merton idealistically formulated that science was characterized by the values of communitarianism, universalism, disinterestedness, and organized skepticism (see Merton, 1968). This formulation is from the 1930s.

Few constructive design researchers believe in the more authoritarian version of science. For them, research programs have to be in dialog with society. This dialog makes research socially robust. Whether it raises debate is more important than facts and knowledge; these are understood as temporary constructs. This is certainly the case in most parts of the constructive design research community. A successful constructive program participates in public discourse and interprets society rather than acts as a legislator. 35

35.The metaphors of “interpreter” and “legislator” are from the Polish-British social critic Zygmunt Bauman (Bauman and May, 2000).

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.