1. Constructive Design Research

In constructive design research the key role is doing design. Constructive designresearch is a small, but important and interesting part of contemporary designresearch. Its roots are in industrial design and interaction design. The cultural, social, and material sensitivities constructive design researchers bring from design practice to research make if different from engineering. It is these sensitivities that give researchers the ability to work with themes in what the Italian designer Andrea Branzi has called second modernity. Although the main drivers of constructive research can be found in technology, contemporary research has a far wider outreach in society.

iFloor was an interactive floor built between 2002 and 2004 in Aarhus, Denmark. It was a design research project with participants from architecture, design, and computer science. It was successful in many ways: it produced two doctoral theses and about 20 peer-reviewed papers in scientific conferences, and led to other technological studies. In 2004, the project received a national architectural prize from the Danish Design Center.

At the heart of iFloor was an interactive floor built into the main lobby of the city library in Aarhus. Visitors could use mobile phones and computers to send questions to a system that projected them to the floor with a data projector. The system also tracked movement on the floor with a camera. Like the data projector, the camera was mounted into the ceiling. With an algorithm, the system analyzed social action on the floor and sent back this information to the system. If you wanted to get your question brought up in the floor, you had to talk to other people to get help in finding books.

iFloor’s purpose was to bring interaction back to the library. The word “back” here is very meaningful. Information technology may have dramatically improved our access to information, but it has also taken something crucial away from the library experience — social interaction. In the 1990s, a typical visit to the library involved talking to librarians and also other visitors; today a typical visit consists of barely more than ordering a book through the Web, hauling it from a shelf, and loaning it with a machine. Important experience is lost, and serendipity — the wonderful feeling of discovering books you had never heard about while browsing the shelves — has almost been lost.

A blog or a discussion forum was not the solution. After all, interaction in blogs is mediated. Something physical was needed to connect people.

A floor that would do this job was developed at the University of Aarhus through the typical design process. 1 The left row of Figure 1.1 is an image from a summer workshop in 2002, in which the concept was first developed. The second picture is from a bodystorm2 in which the floor’s behaviors were mocked up with a paper prototype to get a better grasp of the proposed idea. Site visits with librarians followed, while technical prototyping took place in a computer science laboratory at the university (left row, pictures 3–5). The system was finally installed in the library (left row, picture at the bottom). How iFloor was supposed to function is illustrated in the computer-generated image on the right side of the picture.

1.See Lykke-Olesen (2006).

|

| Figure 1.1 |

iFloor received lots of media attention; it was introduced to Danish royalty, and it was submitted to the Danish Architecture Prize competition where it was awarded the prize for visionary products (Figure 1.2). In addition, as already mentioned, it was reported to international audiences in several scientific and design conferences.

However, only half the research work was done when the system was working in the library. To see how it functioned, researchers stayed in the library for two weeks, observing and videotaping interaction with the floor (Figure 1.3). It was this meticulous attention to how people worked with the iFloor that pushed it beyond mere design. This study produced data that were used in many different ways, not just to make the prototype better, as would have happened in design practice.

Developing the iFloor also led to two doctoral theses: one focusing more on design and technology, another focusing mostly on how people interacted with the floor. 3 Andreas Lykke-Olesen focused on technology, and Martin Ludvigsen’s key papers tried to understand how people noticed the floor, entered it, and how they started conversations while on it. It was this theoretical work that turned iFloor from a design exercise into research that produced knowledge that can be applied elsewhere. In design philosopher Richard Buchanan’s terminology, it was not just a piece of clinical research; it had a hint of basic research. 4

3.Lykke-Olesen (2006), Ludvigsen (2006).

4.See Buchanan (2001), who distinguished clinical, applied, and basic research. Clinical research consists of applying a body of (professional) knowledge to a case. Applied research applies such knowledge to a class of cases. In basic research, application is secondary: the goal is to produce knowledge that may be applied later in applied and even clinical studies.

iFloor is a good example of research in which planning and doing, reason, and action are not separate. 5 For researchers, maybe the most important concept iFloor exhibits is that there is value in doing things. When researchers actually construct something, they find problems and discover things that would otherwise go unnoticed. These observations unleash wisdom, countering a typical academic tendency to value thinking and discourse over doing. A PowerPoint presentation or a CAD rendering would not have had this power.

5.As Pieter Jan Stappers (2007) from Delft University of Technology says.

1.1. Beyond Research Through Design

Usually, a research project like iFloor is seen as an example of “research through design.” This term has its origins in a working paper by Christopher Frayling, then the rector of London’s Royal College of Art (RCA) 6. Jodi Forlizzi and John Zimmerman from Carnegie Mellon recently interviewed several experts to find definitions and exemplars of research through design. According to their survey, researchers

make prototypes, products, and models to codify their own understanding of a particular situation and to provide a concrete framing of the problem and a description of a proposed, preferred state…. Designers focus on the creation of artifacts through a process of disciplined imagination, because artifacts they make both reveal and become embodiments of possible futures…. Design researchers can explore new materials and actively participate in intentionally constructing the future, in the form of disciplined imagination, instead of limiting their research to an analysis of the present and the past.7

However, this concept has been criticized for its many problems. Alain Findeli and Wolfgang Jonas, among others, noted that any research needs strong theory to guide practice, but this is missing from Frayling’s paper. 8 For Jonas, Frayling’s definitions remained fuzzy. Readers get few guidelines as to how to proceed and are left to their own devices to muddle through the terrain. Jonas also says that the term provides little guidance for building up a working research practice — and he is no doubt right.

8.Findeli (1998) and Findeli (2006), Jonas (2007, pp. 189–192). Jonas points out some misunderstandings of Frayling as well.

This concept fails to appreciate many things at work behind any successful piece of research. For example, the influential studies of Katja Battarbee and Pieter Desmet made important conceptual and methodological contributions in their respective programs, even though, strictly speaking, they were theoretical and methodological rather than constructive in nature. People read Kees Overbeeke’s writings not because he builds things but because he has articulated many valuable ideas about interaction in his programmatic and theoretical writings. People read Bill Gaver because of his contribution to design as well as methodology, often against his wishes. 9

9.See Gaver et al. (2004). The Presence Project had already been warned not to turn cultural probes into a method. Other references in this paragraph are Battarbee (2004) and Desmet (2002). Overbeeke is a professor at the Technische Universiteit Eindhoven and Gaver is a professor at Goldsmiths College in London.

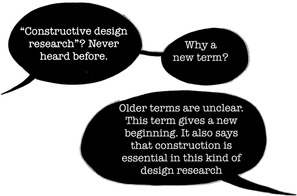

For these reasons, we prefer to talk about “constructive design research,” which refers to design research in which construction — be it product, system, space, or media — takes center place and becomes the key means in constructing knowledge (Figure 1.4). Typically, this “thing” in the middle is a prototype like iFloor. However, it can be also be a scenario, a mock-up, or just a detailed concept that could be constructed.

We focus on leading examples of constructive research but follow Frayling’s empiricist and pragmatist approach rather than offer a definition grounded in logic or theory. 10 By now, we have a luxury: a body of research that does most of the things that Findeli and Jonas called forth. When looking at the 1990s, it is clear that what people like Tom Djajadiningrat in the Netherlands, Anthony Dunne in England, and Simo Säde in Finland did in their doctoral work was solid, theoretically and methodically informed research that could not have been done without a design background. 11 Ten years later, there are dozens of good examples. For this reason, we explicate practice rather than try to define a field with concepts as big as design and research. 12 Introducing a new word is an old academic trick used to avoid difficulties with existing concepts and to keep discussion open, if only for a few years.

10.For example, Zimmerman et al. (2007).

12.Andrea Branzi made a similar point regarding art and design in Burkhardt and Morotti (n.d., p. 65).

1.2. Constructive Research in Design Research

This book looks at one type of contemporary design research. It excludes many other types, including research done in art and design history, aesthetics, and philosophy. It also skips over work done in the social sciences and design management. It leaves practice-based research integrating art and research to others. Similarly, it barely touches engineering and leaves out theory, semantics, and semiotics altogether. 13 This book will not look at research done by design researchers if there is no construction involved, unless there is a clear connection to constructive studies. 14 Finally, it will not review design research that builds on the natural sciences such as chemistry as this research is most typically done in ceramics and sometimes in glass design and conservation. We are dealing with research that imagines and builds new things and describes and explains these constructions (Figure 1.5). 15

13.For history, aesthetics, and philosophy, see Dilnot (1989a) and Dilnot (1989b), Julier (1991) and Julier (2008), Buchanan and Margolin (1995), Margolin and Buchanan (1995), Bürdek (2005), Fallan (2010) and Svengren (1995). For social sciences, see Molotch (2003), Brandes et al. (2009) and Shove et al. (2007). For design management, see Gorb (1990), Borja de Mozota (2003) and Borja de Mozota (2006), Aspara (2009) and Verganti (2009). For artistic and so-called practice-based research, see Mäkelä and Routarinne (2007). For engineering, see Archer (1968). Product semiotics and semiotics are explained in Krippendorff (1989) and Krippendorff (2006), Butter (1989) and Vihma (1995). For an applied perspective, see McCoy (1996). Krippendorff’s MA thesis in Ulm in 1961 was already studying semantics (see Krippendorff, 1989, p. 10, note 5). For theory, consult Branzi (1988).

What constructive design research imports to this larger picture is experience in how to integrate design and research. Currently, there is a great deal of interest in what is the best way to integrate these worlds. This book shows that there are indeed many ways to achieve such integration and still be successful. We are hoping that design researchers in other fields find precedents and models in this book that help them to better plan constructive studies. For constructive design researchers, we provide ways to justify methodological choices and understand these choices.

It should be obvious that we talk about construction, not constructivism, as is done in philosophy and the social sciences. Constructivists are people who claim issues such as knowledge and society are constructed rather than, say, organized functionally around certain purposes, as if in a body or in a piece of machinery. 16 Many designers are certainly constructivists in a theoretical and philosophical sense, but this is not our concern. We focus on something far more concrete, that is, research like iFloor in which something is actually built and put to use. Not only concepts, but materials. Not just bits, but atoms.

16.The classic statement is Berger and Luckmann (1967), although the history of empirical research on social construction of knowledge goes back at least to Karl Mannheim’s sociology and, ultimately, German idealism in philosophy. For a philosophical critique of the notion of practice, see Turner (1994), who mostly — and in many ways, misleadingly, as Lynch (1993) pointed out — built on Ludwig Wittgenstein’s discussion on rule following his criticism of practice.

One of the concerns many design writers have is that design does not have a theoretical tradition. 17 For us, this is a matter of time rather than definition. Theory develops when people start to treat particular writings as theories; for example, such as happened to Don Norman’s interpretation of affordance. It became a theory when researchers like Gerda Smets and Kees Overbeeke in the Netherlands treated it as such.

17.This is the main concern for Poggenpohl and Sato (2009), perhaps partly in response to Krippendorff’s (1995) fear that lacking a disciplinary basis, design always loses in collaboration with other disciplines. Krippendorff’s talk is quoted in Poggenpohl (2009a, pp. 15–16).

For this reason, we focus on research programs rather than individual studies. Chapter 3 explains this concept of program in detail. Here, it is enough to say that research programs always have “a central, or core, idea that shapes and structures the research conducted.”18 Programs consist of a variety of activities ranging from individual case studies to methodology and theory building. This richness is lost in definitions of research through design that tend to place too much weight on design at the expense of other important activities that make constructive research possible.

18.Downton (2005, p. 9).

1.3. What Is “Design”?

Any book on design has to face a difficulty that stems from the English language. The word “design” is ambiguous, as it covers both planning (of products and systems), and also what most other European languages would loosely call “formgiving.”19 The latter meaning is more restrictive than the former, which may cover anything from hair and food design to designing airplanes.

19.Germanic languages usually have separate words for planning and formgiving, including German Gestaltung and Formgebung, and also the more general Entwurf (verb entwerfen), Dutch ontwerpen, and Swedish formgivning. Latin languages build more on the idea of planning, drawing, and projecting, like the Italian disegno and French conception. Other languages, such as Finnish, build on Germanic roots; thus, muotoilu is a direct translation from the Swedish form, while suunnittelu comes from planning.

This book is not about engineering or science, it builds primarily on work carried out in art and design schools. The art and design tradition has an important message to more technically oriented designers. Above all, designers coming from the art school tradition have many ways to deal with the “halfway” between people and things.

People negotiate their way through this halfway with their eyes, ears, hands, and body, as well as their sense of space and movement and many kinds of things they are barely aware of. Although everyone lives in this halfway every second, there are few words to describe it. 20 However, it is the stuff of design education. In Sharon Poggenpohl’s words, it aims at developing sensibilities of visual, material, cultural, and historical contexts. 21

20.Merleau-Ponty 1973. As the philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty noted, this intertwining of the world and people had no name in philosophy. The word “experience” tries to capture it, but it is human-centric and too easy to turn into just another cognitive process. It also tends to focus on significant events rather than the prose of everyday life. The word “interaction,” on the other hand, having its origins in the natural sciences, is too easy to turn into a model of a mechanism. Merleau-Ponty’s term of choice was “flesh,” also a less appropriate choice. Its carnal imagery downplays mindful and social aspects of human existence. This notion is from Merleau-Ponty’s (1963) and Merleau-Ponty’s (1973) posthumously published essay “The Intertwining — The Chiasm.” The word “prose,” also from his posthumous writings, carries a heavy meaning. As Merleau-Ponty noted, our world is mostly prosaic rather than poetic. Certainly, prose dominates in design (Merleau-Ponty, 1968 and Merleau-Ponty, 1970, pp. 65–66). Somewhat similar ideas are apparent in many other writings in design: design is about capturing something in the gray area between people and the things around them. In addition to Poggenpohl’s essay quotes in this paragraph see, for example, Seago and Dunne (1999) and in particular Pallasmaa (1996) and Pallasmaa (2009), whose perceptive analysis of architecture is well in line with this understanding of design (especially Pallasmaa, 2009, pp. 11–22).

21.Poggenpohl (2009a, p. 7). She follows Polanyi’s distinction between tacit and explicit knowledge, which we try to avoid in this book, as we believe it unnecessarily dramatizes the difference between design and research.

There is no reason to be romantic or cynical about these sensibilities. Designers trained in the arts are capable of capturing fleeting moments and structures that others find ephemeral, imaginative, and unstable for serious research. They are also trained in reframing ideas rather than solving known problems. Above all, they are trained to imagine problems and opportunities to see whether something is necessary or not. It is just this imaginative step that is presented in discussions on innovation in industry. 22

22.The second point builds on several writers. Characterizing design as an attempt to change existing situations to preferred ones comes from Herbert Simon (1996). The idea that designers reframe things through imagining several preferred situations rather than framing a problem and solving it comes from Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber (1973) and Richard Buchanan (1992). For recent discussion on design in innovation, see Verganti (2009).

1.4. Industrial Design and Interaction Design

Even in this narrow sense, design is a complex category that covers many subjects ranging from paper machines to the conceptual designs of, say, Droog Design in the Netherlands. 23 This book does not try to cover all of these topics; it mostly builds on work carried out in industrial design and interaction design — the main hubs of constructive design research (see Figure 1.6).

23.Some caution is needed here. While it is easy to classify the work of groups like Memphis and Droog Design, and today, critical design, as conceptual work aimed at changing perceptions and ways of seeing things in design, it is equally true that these groups worked through material. Their work was certainly not designed to celebrate immaterial things like concepts. For a similar point regarding relational aesthetics, see Bourriaud (2002, pp. 46–47).

|

| Figure 1.6 |

Industrial design and interaction design differ in many ways. The most notable differences are in tradition and technology: industrial design has roots producing material goods, and interaction design is based on computer science, film, and Web design. Industrial design is product-oriented, three-dimensional, and relies heavily on sketches, mock-ups, models, and physical prototypes. Interaction design is time-oriented and relies on personas, scenarios, narratives, and software prototypes. Also, the skills required for each type of design are different.

Still, over the past 15 years these specialties have evolved side by side with many interaction designers with a background in industrial design and sometimes vice versa. Also, research communities overlap, sharing processes and many working practices. 24

24.As with most concepts, a dose of caution helps a designer to not get distracted. If one looks at job offerings, interaction design is mostly about interfaces for the Web, computers, and machinery. In this sense, interaction design is a novelty in design, although its history goes back far longer than design folklore says. Many designers worked with interaction far before graphical user interfaces came to light in the 1980s. In a wider sense, interaction design may mean those things in which people meet their environment through some kind of computation. Here, interaction design is scarcely a novelty. For example, there are many industrial design programs that do not offer interaction design specialties. If industrial and other designers have been using interactive devices all along without specialized training, then why change? A word of warning about industrial design is also warranted, but this warning is about the relationship to product design. Usually, industrial design is an umbrella and product design a part, but the reverse holds in places like the Glasgow School of Art.

We believe that constructive design research continues to build on these two specialties, but with more overlap. One set of reasons lies in its technology, which is making interaction design an increasingly important design specialty. When information technology has “disappeared” from gray boxes to the environment, interaction designers increasingly deal with problems familiar to industrial designers. 25 Industrial designers, on the other hand, are increasingly using information technology (IT). Importantly, information technologies have no obvious shape. The key skills in coping with IT are not redoing and refining existing forms but imagining interesting and useful concepts that people want. 26

25.This sentence builds on Mark Weiser’s (1991) idea of ubiquitous computing.

26.Thackara (1988), Redström (2006, pp. 123–127), Buchanan (2001). For how the object of art got dematerialized, see Lippard (1997).

1.5. Design Research in Second Modernity

Behind current research lie social forces larger than technology. After the reconstruction period after World War II, the 1960s witnessed major changes in society. Western economies became consumer driven and an ecological crisis influenced it, higher education democratized, and pop culture merged with youth culture. Media became global, taste became democratized, and there was an upheaval in politics as traditional loyalties started to crack. In the 1950s, the main arbiters of taste were the educated upper middle classes, but by the mid-1970s, up-to-date design built on sources like pop art.

However, when the 1980s arrived, society was more stable. Andrea Branzi, one of the main revolutionaries of design, wrote:

During the period of forced industrialization that lasted from 1920 to 1960, the hypothesis had been formed that design ought to be helpful in bringing about a standardization of consumer goods and the patterns of behavior in society. Its work lay in a quest for primary needs…. Along that fascinating road design has hunted for many years the white whale of standard products, products aimed at the neutral section of the public’s taste, products intended to please everyone and therefore no one…. Then, in the mid 1960s, things began to move in exactly the opposite direction. The great, pyramid-shaped mass markets, guided by enlightened or capricious opinion leaders, gradually disintegrated into separate niches and were subsequently reformed into new and multicolored majorities. Design had to skirt its attention from mass products to those intended for limited semantic groups. From objects that set out to please everyone, to objects that picked their own consumers. From the languages of reason to those of emotion…. Then the process of transformation slowly came to an end. The mutation was complete and it is now possible to say that a new society, with its own culture and values, has taken on a fairly stable shape. 27

27.Branzi (1988, p. 11). Castelli 1999. Contemporary design reflects change in society in that there is no common style or criteria for style today, as Catherine MCdermott 2008 and Penny Sparke 2008 have noted.

For designers, Branzi’s second modernity has opened many new opportunities. 28 The first ones who seized these opportunities were graphic, industrial, and interaction designers. There are also many other characters who populate design today: service designers, design managers, community designers, and researchers. As Branzi recently noted, design has become a mass profession. 29

28.See Maldonado (1972, pp. 27–29). For an accessible version of Maldonado’s thinking, see Gui Bonsiepe (2009, p. 125), who rightfully pays attention to a curious lack of design in a plentiful discussion of modernity in the social sciences, and compares this to Maldonado’s concerns:The debated tackling of the theme of modernity … have never taken the design dimension into consideration: design has been absent …. In [Maldonado’s] essays, design is not merely understood as an incidental phenomenon or a secondary theme of modernity but, on the contrary, as a driving force of modernity itself. In the practice of design, modernity finds itself. Being radically modern means: inventing, designing, and articulating the future or modernity.

29.Branzi (2010).

There is some friction between the two modernities. Institutions like universities react to society slowly and tend to be run by those who came to the field in the first modernity. However, many designers and researchers commute across the boundary with ease. As design has become more diversified in ethnic and gender terms, such skill is in high demand; there is no way back to the first modernity dominated by white European and American men.

Research plays an increasingly important role in this transition. As Branzi’s colleague Antonella Penati noted, design is coming of age. Design education was typically established in universities after World War II, making it a relative newcomer in universities. However, design is now in its third generation. As Penati explained, design is currently maturing by embracing new computer-based technologies and research. 30 Research helps designers to navigate the second modernity (Figure 1.7).

30.Penati (2010).

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.