8. Design Things

Models, Scenarios, Prototypes

Perhaps the most conspicuous feature of constructive design research is that it constantly borrows methods and processes from design practice. It is these “design things” that bring people together in research. When doing user studies, researchers use various props. When working in the studio, they bodystorm and role-play ideas to get a firsthand understanding of how people would experience them. When working through these ideas in design, they use moodboards, scenarios, mock-ups, and prototypes. Methods like these bring those design sensitivities that are the crux of designers’ professional skill into research. Just like the theoretical background we talked about in Chapter 7, these methods create commonalities between the three approaches outlined in this book.

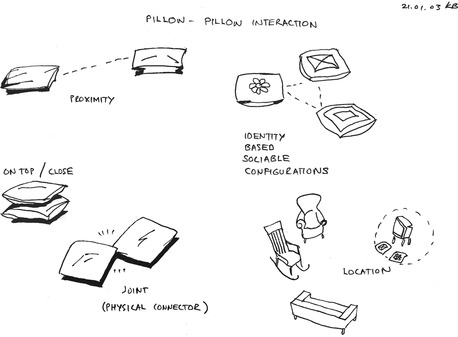

The Swedish computer scientist Pelle Ehn recently argued that design is “thinging.”1 This sounds mysterious, but the bottom line is that he describes a down-to-earth approach to design. It is his latest attempt to explain why designers get far better results with rough cardboard computers than using sophisticated systematic methods like flowcharts and simultaneous equations. In Ehn’s opinion, the reason for the success of these rough “things” was that they brought people to the same table and created a language everyone could share. 2 Design things populate design studios and fieldwork. They range from quick black-and-white sketches on any piece of paper all the way to those skillfully finished prototypes that researchers construct in places like Eindhoven and London. 3

1Ehn (2008) and Ehn (2009).

3There are a few precursors to this argument, most notably Henderson (1999; see also Kurvinen, 2005). Ehn’s argument about design things is social institutional and, as such, an alternative to those explanations in which design is seen as primarily a cognitive activity (Lawson, 1980 and Lawson, 2004; Cross, 2007; Visser, 2006).

The key point Ehn makes is that these things play an important role in keeping people focused on design. His argument is etymological. The English word “thing” has Germanic roots. This root is the word ting, which in Scandinavian languages still means an “assembly,” where people gather to make decisions about the future of the community. If we accept an etymological argument like this, design things are like town hall meetings: places where people gather to decide collectively where to go. 4

4The link between using design things and making the design process more democratic is obvious and has been made by many writers, although usually in less colorful language than Ehn (see Muller, 2009; Säde, 2001; Shaw, 2007; Moon, 2005; Pallasmaa, 2009).Ehn’s argument is similar to that of Bruno Latour and is also indebted to Martin Heidegger’s philosophy. A member of the group led by Ehn, Giorgio De Michelis (2009, p. 153, italics added), wrote:From this perspective, as De Michelis noted, design appears as one of those elementary practices in which human beings experience not yet existing things.Similar semantics also works in Finnish, although etymology of the word “asia” is of course different.

In a short essay published in Poetry, Language, Thought Martin Heidegger recalls that the German word “ding” (sharing its root with the English word “thing”) was used to name the governing assembly in ancient Germanic societies, made up of the free men of the community and presided by lawspeakers. It should be noticed that also the Latin word for thing, “res,” occurs in “res publica” (“republic” in English). So things are the issues governing assemblies take into consideration, the issues raising public concern. The word “thing,” therefore, does not indicate genericity, absence of specification, but impossibility of specification. Things are not without interest: on the contrary, they are what merit our attention. Things are matters of concern because they can’t be reduced to any specification: Things exceed the way we classify them and are open to discovery and surprise.

Design things are indispensable tools for transforming designers’ intuitions, hunches, and small discoveries into something that stays — for instance, a prototype, product, or system. 5 They provide the means for sketching, analyzing, and clarifying ideas as well as for mediating ideas and persuading others. 6 In Bruno Latour’s philosophical language, design things turn weak hunches into stronger claims. They also translate many types of interests into joined strongholds and provide tools that take design from short to long networks. 7 This ability to gather people to talk and debate without any command of special skills is what is needed to work with systems design methods. Flow diagrams and other rationalistic tools cut too many parties out from design, creating a caste system. Understanding these forms requires training, and the mere use of these tools tells non-experts to stay away (Figure 8.1). 8

5Seago and Dunne (1999, p. 16).

6For the politics of prototyping, see Henderson (1999). Juhani Pallasmaa (2009, pp. 58–60) wrote about models in architecture, but his description no doubt works in design too:

Drawings and models have the double purpose of facilitating the design process itself and mediating ideas to others…. Even in the age of computer-aided design and virtual modeling, physical models are incomparable aids in the design process of the architect and the designer. The three-dimensional material model speaks to the hand and the body as powerfully as to the eye, and the very process of constructing a model simulates the process of construction. Models are used for a variety of purposes: they are a way of quickly sketching the essence of an idea; a medium of thinking and working, of concretizing or clarifying one’s own ideas; a means of presenting a project to the client or authorities; and a way of analyzing and presenting the conceptual essence of the project…. The architect moves about freely in the imagined structure, however large and complex it may be, as if walking in a building and touching all its surfaces and sensing their materiality and texture. This is an intimacy that is surely difficult, if not impossible, to simulate through computer-aided means of modeling and simulation.

8Models have received a lot of attention in architecture recently. Karen Moon (2005) wrote extensively about models in architecture, largely focusing on historical examples, but also on the likes of Eero Saarinen, Cesar Pelli, Norman Foster, Toyo Ito, Skidmore, Owings, & Merrill, and, of course, Frank Gehry.Despite swings in popularity and purpose, architects still construct models mainly to develop their ideas and communicate them to clients and financiers. Models communicate a purpose, and often have a utopian character, and although for many architects, models are but stages in a process in which only the final product — usually a building or a plan —matters, they have recently achieved a celebrity status of sorts, having a market in which models are bought from studios sometimes at the cost of hundreds of thousands of dollars. Buyers are usually museums that have room for often precarious models.Moon focused on architecture, where issues like scale, lighting, and photography are important, but some of her observations may also apply to design. In particular, the functions of models are largely the same. Designers face questions about the artistic and sculptural quality of their work just as architects do. Their models can also be expensive to build. In the main, however, design models are cheap, in-the-moment creations meant for critiques in the design process, and although there is already a market for design sketches and prototypes, the market for design models is less developed.No doubt, this will change when design museums become more common and gain importance. After all, the key factor in developing a market for architecture models has been the rise of architecture museums. Design prototypes are also small, which helps in creating this market.Another recent book on models in architecture is Morris (2006).

Most writing about modeling and prototyping in design has been about the construction, technical qualities, and functions of prototypes and has typically tried to classify prototypes and other expressions by their function, technology, or place in the design process. 9 In contrast, writers like Ehn give a theoretical and philosophical grounding on design things and shift attention to what designers do with them. 10 To understand design properly, we need to look at design things in research practice.

9Säde (2001) is still a good introduction.

10For recent discussion, see Zimmerman et al. (2007).

8.1. User Research with Imagination

Many methods in constructive design research are immediately familiar to any social scientist, psychologist, or engineer. Researchers collect data at various phases of the design research process by doing interviews, making observations, administering questionnaires, and collecting many types of documents using textbooks from more established disciplines. 11 If there is something specific in how designers gather data, it is their frequent reliance on cameras and videos for data collection. 12 Another difference is that designers are not usually afraid of influencing people they study; they do not try to be flies on the wall.

11Sleeswijk Visser (2009).

More significant differences, however, go back to the imaginary nature of design. Designers are expected to imagine new things, not to study what exists today. In ordinary life, people are inventive but within the bounds of everyday life. 13 To get people into a more creative mood, constructive design researchers use several techniques that differentiate them from the social sciences. One technique is vocabulary, which often fails at crucial moments. Few people have an extensive vocabulary for describing things such as materials, colors, shapes, spaces, and other things of immediate interest to designers. Designers have to find ways to make people imagine.

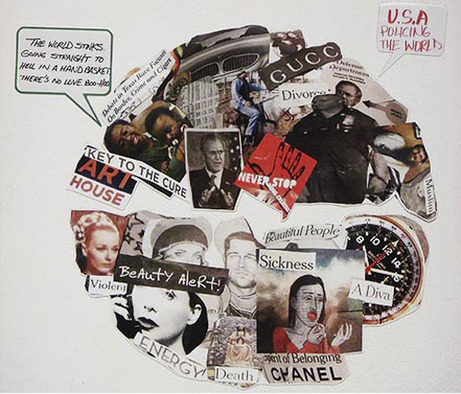

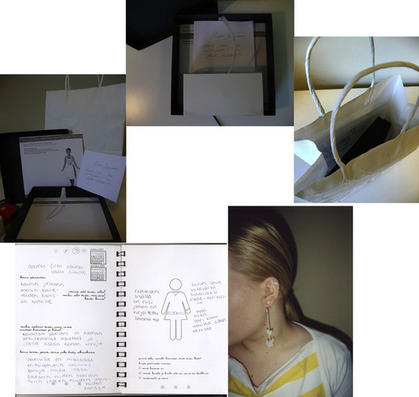

These inventive methods are heavily indebted to design practice; they try “stretching” the context rather than describing it in detail. With these methods, researchers try to get at “poetic” aspects of life: things that exist in imagination only or are unique. Among well-known examples are cultural probes and Make Tools that are routinely used in constructive design research (Figure 8.2 and Figure 8.3). 14

14For probes, see Gaver et al. (1999); for Make Tools, see Stappers and Sanders (2003).

|

| Figure 8.2 Probes and probe returns from a study of women’s jewelry in Chicago (2009) and girl’s jewelry in Helsinki (2006). (Pictures courtesy of Petra Ahde-Deal.) |

For example, in a probe study in Pasadena in 2006, people were given empty globes and were asked questions like what Earth would say if it could talk. They did this by gluing clips from the New York Times on the globe. 15 Make Tools, on the other hand, were developed to capture people’s imagination about how they make things rather than what they say or do. Make Tools were created to complement marketing research based on what people say in interviews and ethnography based on observations of what people do. 16 This logic also applies to many other methodologies, such as “magic things,” which are used to capture sparks of imagination in those fleeting moments of life that usually disappear before anything valuable emerges (Figure 8.4). 17

Also, designers regularly use things that force them to experience firsthand what it means to, say, have blurred vision, problems in hearing, or arthritis. 18 In the most extreme cases, researchers may even “go into a role” to see how people respond to old age, disease, and sickness. Here they follow the example of designers like Patricia Moore. Such firsthand knowledge is a way to gain empathy, sensitivity, and the ability to spot problems and identify opportunities.

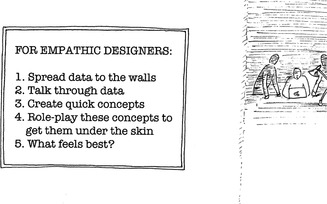

8.2. Gaining Firsthand Insights in the Studio

This lively imagined world has to be brought into the studio. The aim is to get firsthand insights into how people experience their environment. 19 Things like space, proportions, distances, weight, and proximity need to be made concrete so they can be discussed within the design group. For design researchers, this context has to be at their fingertips, not just in their minds: they have to be able to touch it and play with it. 20

19See IP08 (2009).

20See Poggenpohl (2009a, p. 7) and the reference to Maurice Merleau-Ponty in note 19 in Chapter 1.

Studios are built to function as knowledge environments—a phrase designer Lisa Nugent used to describe research-oriented studio spaces. 21 There are several reasons for building knowledge environments and doing interpretation in workshops in these environments. First, they test ideas. Things that survive these workshops are certainly robust because they are tested not only in talk but also through more rich bodily, social, and playful imagination. Second, they help to create joint understanding. They have an intensity that drives curiosity and creates a sense of accomplishment. This work often leads to rewriting research questions. Informed by field data, researchers are able to spot opportunities far better than before. In this early phase, researchers typically also start to create first design concepts (Figure 8.5 and Figure 8.6).

Researchers typically play with these design concepts to gain insight into how people would experience them. Well-known practices are bodystorms, acting out scenarios, and role-plays in which participants switch roles to understand data from many points of view.

An iconic example comes from IDEO, in which bodystorming — the name refers to brainstorming — was once used to study the idea of placing sleeping facilities in airplanes under the seats. This idea might be economically viable but might not feel particularly good. There was a need to know what it would feel like to sit under other people in a small closed space and how it would feel to sit above people who are sleeping under the seat. No complex technology was needed for this exercise. The only props needed were chairs put into a row and a few pillows and blankets. Some people sat on the chairs, while others tried to sleep under them (Figure 8.7). 22

Even organizational simulations can be done this way. Researchers sometimes use humble things like matchboxes, paper cups, and Legos to stage organizational structures and processes. Again, these props are simple, but they generate a genuine feeling of excitement when they are used (Figure 8.8).

|

| Figure 8.8 (Picture courtesy of Aalto University’s Department of Design.) |

Like designers, design researchers prefer to work in multidisciplinary and multicultural workshops to quickly expose themselves to multiple perspectives. Usually, these workshops begin with presentations of data and go on in the classical brainstorming mode, typically into an open discussion in which criticism is not first allowed. It is only later that discussion points out problems in interpretations and possible design ideas emerge from these discussions. The preference for working together has its origins in design practice, where experience has shown that many eyes see more. 23

Here, a firsthand sense of design things is particularly important. The work is experimental and playful, and firsthand bodily and social feelings are crucial. Partly for these reasons, most designers are wary of relying on technology only. Thus, even though the Web has extended the possibilities for design research with techniques like “crowdsourcing” and online testing of concepts, it has not caught on in design. Most likely the reason goes back to the disembodied nature of the Web. 24 Design research practice builds heavily on bodily and social interaction, which is difficult to do in the virtual domain.

8.3. Concept Design with Moodboards, Mock-ups, and Sketches

After studio work, constructive design researchers go on to design development, which begins with sketchy ideas and ends with prototypes. Previous phases of research have led to insights and design hypotheses, but many things such as forms, materials, look and feel, mechanic design, and interaction design are still open. These issues are handled with methods borrowed from design practice, including moodboards from fashion design, storyboards from film making, and scenarios that have their origins in the military. With these methods, researchers are able to bring their design skills and intuition into the research process. 25 Up-to-date practice in scenarios starts with scriptwriting and ends with 3D animations, concept films, and virtual reality. 26

25For moodboards, see Lucero (2009); for scenarios, see Carroll (2000).

For example, researchers explore how the design looks and feels; its color, light, and shade; surfaces; contrasts; and materials with sketches. They also explore structures and functions with these sketches. 27 Some sketches are 3D studies in clay and other cheap modeling materials like styrofoam. These sketches are done to study scale and feel in the hand and on the body, as well as mass, form, and composition. Later, they may also turn to studies of materials and mechanisms. It is important to choose the appropriate level of coarseness and not get into details before the basic idea is mature (Figure 8.9).

|

| Figure 8.9 (Redrawn by I. Koskinen, March 2011.) |

For studies of form and scale, researchers do mock-ups from cardboard, wood, cheap plastics, and other materials at hand. Mock-ups are simple and cheap, and they can be changed easily for feedback. Also, they facilitate communication, enable participation in the design process, and encourage imagination. As they are not limited to current technology, they unleash imagination. 28 Even though the past few years have seen a rapid technological development with 3D printers being used in design and design research, mock-up materials are typically low-tech (Figure 8.10). 29

28Ehn (1988a, pp. 335–336).

29See Caption (2004). For lo-tech approach, see Ehn and Kyng (1991).

|

| Figure 8.10 Sketches for an interactive robot from Carnegie Mellon’s Snackbot study, which developed a mobile and autonomous robot for delivering snacks to people at Carnegie Mellon University. 30 30.See snackbot.org and Lee et al. (2009). (Picture by Eric Glaser, thanks to Jodi Forlizzi.) |

Sketches are helpful in nailing down design ideas; they also help to understand things like service flow, scale, form, and how people will interact with the concept. They are not meant, however, to study issues like technology, materials, the look and feel of the idea, details of user interfaces, or details of how the concept functions. For these studies, researchers use scenarios — often verbal, sometimes visual (Figure 8.11).

8.4. Prototyping

At this stage, design concepts are grounded in experience, but they still remain barely more than images. To get an idea of tangible things like mechanics, behavior, and materials and colors, researchers build prototypes. Prototyping is the only way to understand touch, materials, shapes, and the style and feel of interaction. It is also the only way to understand how people experience product concepts and how they would interact with them. As researchers in Eindhoven explained:

Design always goes through many explorations. The exploration within design research must be as abundant, but must also be more structured and systematic than in the normal design case. Reflection on a multitude of prototypes might, e.g., be done by trying to categorize them on dimensions of similarity and difference.The form theory course in [Wensveen’s study] resulted in more than 100 models that could be categorized…. Reflection on this categorization informed the rest of the design process. This insight can only be gained by making all these prototypes, and not by thinking about them.31

31Overbeeke et al. (2006, p. 12).

Research prototyping shares these functions with industrial prototyping, but differs from it in several other respects. 32 For example, researchers are not usually interested in technical testing, robustness, safety, or manufacturability. 33 Also, they do not need to sell their ideas to product development, management, and customers. Prototyping has its share of problems. Since prototypes are future oriented, they often lack connection to the present. Also, there is a danger of “tunnel vision” in which researchers elaborate the prototype rather than question its premise. Finally, there is a danger of paying too little attention to social aspects of use, as technology development takes priority (Figure 8.12). 34

32Säde (2001, p. 55). For differences between research prototypes and industrial prototypes, see Chapter 4, which quotes Frens (2006a, p. 64).

33Ross (2008), Hummels and Frens (2008) and Frens (2006a). Some research groups, however, have gone into that direction, most notably researchers in Interaction Research Studio of Goldsmiths College, London. See gold.ac.uk/interaction/portfolio/, retrieved March 10, 2010.

34See Mogensen (1992, pp. 5–6.

Somewhere between mock-ups and prototypes are “experience prototypes,” which Buchenau and Fulton Suri defined as representations designed “to understand, explore or communicate what it might be like to engage with the product, space or system we are designing.”35 Experience prototypes create a shared experience and provide a foundation for a common point of view in design teams. They are used to understand existing experiences and contexts, to explore and evaluate design ideas, and communicate ideas to audiences. With programmable toys like Lego Mindstorms it is also possible to build simple mechanisms and programs into the mock-ups to see how they function and what kinds of messages their behavior conveys.

8.5. Platforms: Taking Design into the Field

Prototypes may be ingenious and well made, but they remain researchers’ guesses about a possible product unless they are somehow studied. Over the past few years, researchers have started to do increasingly ambitious research to see how their prototypes work. Research has recently gone beyond brief site visits, evaluation studies, and tests. 36 When working with new technologies that have little origin in current practices, the best way to follow these technologies and practices is to build them, hand them to people, and then study what happens. 37

36See Kankainen (2002).

Researchers have increasingly given people freedom to do whatever they will with designs. For example, Ianus Keller gave his Cabinet design to several design studios for a month to see how designers interacted with it. 38 Another ambitious study was Morphome, in which all designs were repeatedly studied with people in everyday life for weeks and months. 39 The reasons are well explained on the Web site of Interaction Research Studio at Goldsmiths College, London:

38Keller (2005, p. 119ff).

39Mäyrä et al. (2006), Koskinen et al. (2006).

Designing, building and testing prototype products is at the centre of our research…. We build our prototype products to a very high level of finish and technical robustness, which allows them to be tested for long periods in everyday life, and to be shown in lengthy exhibitions with minimal maintenance. Currently we are moving towards batch producing prototypes, so that we can disseminate 50–100 instances of a given design for extensive field trials.40

40gold.ac.uk/interaction/portfolio/, retrieved March 26, 2011.

In addition to field studies, many researchers have recently built platforms for observation. Radiolinja was a study about camera phones in Helsinki between 1999 and 2002. Researchers followed camera phone messaging through the network of Radiolinja, which was Helsinki Telephone Company’s mobile carrier. In this system, people sent multimedia messages to the Radiolinja network, which distributed them to recipients’ phones as well as a log site, where the message could be browsed through a Web link. Through the log site, researchers were able to follow messaging. They followed it daily to see how people used this new technology (Figure 8.13). 41

|

|

| Figure 8.13 |

There is little new in these platforms. They have existed for a long time under various names, ranging from panel studies in the social sciences to field stations in agriculture, and field hospitals in medicine. In industry, the most comprehensive platform so far comes from Philips Research, which has developed an Experience Research Cycle for studying how ambient intelligence could be embedded into everyday life on a large scale. The cycle begins with a context study that maps context without technology, usually with observations. It continues to laboratory studies that test usability and user acceptance in controlled environments that enable detailed and accurate qualitative and quantitative studies. It ends with field studies that validate the results of laboratory studies and focus on the long-term effects of technology. 42

42De Ruyter and Aarts (2010).Some global companies have organizational models for achieving similar results. They have for so long placed their creative studios in fashionable places where designers can observe the world without effort.We have already mentioned Olivetti as a historical example in Chapter 2, but the practice still exists today; for example, one of Toyota’s Creative Studios is in Chicago’s fashionable Bucktown. Similarly, the car industry has long had its main design studios in the world’s leading car culture, Los Angeles. Harvey Molotch (1996, pp. 257–258) wrote an elegy to Southern California:There is also the notion of the “living lab,” which we find confusing. Again, the idea here is to build environments in which people are free to do things, but which can be followed with permanent research instruments. This term gained some popularity in Europe from 2005 to 2008.

Those in California auto design disagree among themselves on what, if anything, may be the basis for the region’s special design role. For Hiroaki Ohba, executive vice president of Toyota’s Calty Design, the company’s Orange County location is particularly stimulating, among other reasons because “Newport Beach is a museum for automobiles and an ideal place for the automobile designer…. We see many antique cars in Newport Beach.” There are also “more exotic cars on the streets of a place like Newport Beach (Porsches, Ferraris), more, according to Ohba, than one would find in Germany or Japan. The youth of California have for generations been great style experimenters. One auto designer told me that the fashions on Melrose Avenue, a 1990s hot strip of boutiques and high-end junk shoppes for the affluent young, influence car design. The shapes and colors of jewelry, the textures and combinations of outfits, all may end up in design details…. Even if not consciously inventorying “the trends,” designers are alert to such messages from the streets and shop windows. The GM California studio chef says he likes to take “a few of our guys and drive along the beach … to see what people do on weekends with their vehicles.” The Chrysler vice president for design explains his company’s presence in Southern California as taking “advantage of the local culture there.”

Platforms like these enable many kinds of studies. For example, in Radiolinja the main focus was on how people design their messages and respond to them, but researchers also calculated statistics of traffic, message types and networks, and time series analyses. 43 Even more complex platforms for studying camera phones were built in Berkeley, leading ultimately to the redevelopment of services like Flickr. 44 With platforms, researchers can follow things over time and do comparisons between technologies and their variations. Another benefit of platforms is that they pave the way to more complex research designs, including doing quasi-experiments to compare different technologies and designs. 45

43See Kurvinen (2007), Koskinen (2007). For other large-scale field studies in context, see Jacucci et al. (2007), who studied multimedia systems for rock and jazz festivals and even a massive, 400,000 participant World Rally Championship event in Finland.

45For the “breaching experiment,” see Crabtree (2004). For another approach, see Binder (2007) and Binder et al. (2011), who talks about design:labs.

8.6. Design Things in Research

Design things like moodboards and prototypes populate the spaces in which designers work. Likewise, they populate constructive design researchers’ studios and the pages they write. The reasons for using them in research are the same as in design. They are an effective way to bring people to the same table to imagine better futures together. Most important, they make it possible to probe and discuss those sensuous, embodied and social things that are central to design — like colors, how materials feel on skin and the shapes of objects. Few people have a reliable vocabulary to talk about them. Inventive methods have a place in design for this reason alone. We do not know why these things work, only that they do work. 46

46However, see Kurvinen (2007) for a study of how people interact with design things in meetings.

This chapter looked at how design things are used over the design process. In early-stage user studies, these things are used to bring imagination and playfulness into these studies and to make imagination shareable. Later, when design enters a concept design phase, design things are used to develop concepts for products and systems. When research enters the design phase, researchers create models, mock-ups, and prototypes. Even later, with concepts and prototypes at hand, constructive design researchers usually study them with people to see how their ideas work. It goes without saying that for different types of research tasks, different methods are used. Also, there are few studies in which all of these steps are used; this is not a mechanical sequence, it is a creative process. 47

47But see Wensveen (2004) and Ross (2008).

Design things are colorful, playful, and usually projective: they illustrate future possibilities. They also fail occasionally. When the Presence Project asked people to imagine Biljmer in Amsterdam as a body, most participants were perplexed and did not know what to do. 48 This playful, exploratory, and projective stance made it difficult to think about these things logically. Design things are not traditional research instruments.

48Gaver (2002).

It is this richness, however, that creates touching points in life. Philip Ross did not need to be able to explain everything that happens in his clay models because people connected to them in many ways, not just intellectually; people can study and discuss these models. This is more important than whether or not design things can be explained in detail. In still broader terms, design things enable designers to capture Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s “flesh” — that poorly understood netherworld in which humans meet things from which designers get much of their inspiration. 49 The specific skill of a designer is to be able to put a concept into a workable form. Ideas may fly in any conversation, but methods are needed to turn these ideas into prototypes, products, or systems.

49For this weight, see Chapter 1 and our inspiration, Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1968) and Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1970). See also Chapter 5 and the quote from Fulton Suri in that same chapter (Fulton Suri, 2011).

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.