7. How to Work with Theory

One observation from this book is that constructive design research has roots in many theoretical traditions. When we traced the intellectual influences behind research, we discovered references to what philosophers call post-Cartesian philosophy. For example, field researchers may refer to debates on user experience, but see this concept through symbolic anthropology, symbolic interactionism, pragmatism, or phenomenology. Showroom researchers, for their part, build on things like surrealism and Critical Theory. Importantly, these are open ways of thinking where they do not define what is important in design. They give priority to design; research follows design rather than vice versa. Contribution to knowledge happens in design pieces and frameworks that reflect designs. Theory and philosophy remain in the background, and are typically the domain of the most senior members of research communities.

This chapter looks at the theoretical background of constructive design research. When we look beyond individual studies, we find a few recurring theoretical sources. When we look at what inspired the selection of these sources, we see how most constructive design researchers have roots in twentieth century Continental philosophy, social science, and art. This chapter elaborates on the three methodological approaches outlined in chapter 4, chapter 5 and chapter 6. At the surface, the three approaches may seem like independent silos; if we go beyond the surface, we find a more common core. This shared core also explains why constructive design research differs from the rationalistic design methodologies discussed in Chapter 2.

Interaction design has inherited its methodological premises from computer science. Before that time, computers were in the hands of experts trained in rational systems development methodologies. When computers entered workplaces and homes in the 1980s, systems failed because people could not effectively use their new computers. Systems designers had a very different conceptual model of the system from the workers who used these systems to complete tasks. 1 Software developers turned to cognitive psychology for a solution: the driving design mantras became “ease of use” and “user friendly.”

1.One of the most important voices in design at this time was the cognitive psychologist Don Norman, one of the early user interface researchers at Apple. In his view, human action proceeds in a cycle where people set goals, transform these goals into intentions and plans, and then execute these plans against a system. Following an action, people observe feedback from the system to assess how their actions change the circumstances; they evaluate whether their action advanced them toward their goal. In this classic feedback model, with a basis in information theory and cybernetics, humans functioned as information processors. To operationalize this model, interface designers needed to think about how a system could communicate its capabilities in a way that helps users generate appropriate plans, and they needed to provide feedback that clearly communicated how an action advanced a user toward a goal (Norman, 1988, pp. 46–49).

However, many products failed because they did not do what the users wanted or even needed them to do: no amount of massaging the details of the interface could address the fact that computers were often doing the wrong thing. First, the key notion of “task” tied it to behaviors and practices that exist but did not assist designers in imagining what should be. Second, there was a false universalistic belief that all people are the same, and it would be possible to find an optimal interaction solution that would persist forever. Third, this theoretical perspective implied that theory should guide design, which was a hard sell to designers. 2

2.However, as John Carroll noted, this is not how human–computer interaction (HCI) or interaction design actually works. He described how the thing often precedes the theory (Carroll and Kellogg, 1989). Direct manipulation interfaces, as an advance to command line interfaces, appeared roughly 20 years before Schneiderman (1983) detailed the cognitive theory describing why this works. Xerox created the mouse as a pointing device before Stu Card performed the cognitive experiments that demonstrated this as an optimal pointing solution (Card et al., 1978). Bill Moggridge (2006, p. 39) relates that:Examples of earlier direct manipulation interfaces were NLS (oNLine System), which was an experimental workstation design including a mouse and standard keyboard, and a five-key control box used to control information presentation. On December 9, 1968, Douglas C. Engelbart and the group of 17 researchers working with him in the Augmentation Research Center at Stanford Research Institute in Menlo Park, CA, presented a 90-minute live public demonstration of the online system, NLS, they had been working on since 1962. An earlier example is Ivan Sutherland’s Sketchpad, which was one of the first CAD-like programs. It laid out the idea of objects and object-oriented programming. It was about touching “things” on the screen and motivated the development of NLS. As this history tells, theory came after the fact.Finally, it was increasingly clear that social aspects of work, including context and culture, play a significant role in how people use technology.

Stu joined Xerox PARC in 1974, with probably the first-ever degree in human-computer interaction. Doug Engelbart and Bill English had brought the mouse to PARC from SRI, and Stu was assigned to help with the experiments that allowed them to understand the underlying science of the performance of input devices.

For reasons like these, new ways to bring research into design were needed. 3 There was a need to bring experimentation and “craft” into design research to more effectively imagine what could and should be. Researchers in the emerging field of interaction design turned away from cognition to post-Cartesian thinking: phenomenology, pragmatism, interactionism, and many strands of avant-garde art that connected designers to things like psychoanalysis and existentialism. These philosophies provided consistency and direction but encouraged exploration rather than prediction. 4 They encouraged using judgment and non-symbolic forms of intelligence. They also placed design in the center of research and saw theory as explication that comes after design. Finally, this turn connected design to the human and social sciences that had gone though a “linguistic turn” and “interpretive turn” two decades earlier. 5

3.These frameworks, sometimes referred to as Design Languages (Rheinfrank and Evenson, 1996), attempted to explicitly document interaction conventions so other designers could more easily pick up and apply to their own designs. While similar to Christopher Alexander’s (1968) concept of pattern languages, these were intentionally constructed conventions, not conventions arising from the longer process of social discourse between designers and users. They were similar to corporate style guides for printed/branded materials found in communication design, but they needed considerably more flexibility to allow for unanticipated future actions. Probably the best known of these frameworks was Apple’s Macintosh Human Interface Guidelines. This was an early type of intentional design theory to emerge from the process of making new products and services.

4.The most important historical precursors came from the 1980s. Key writers in America were philosopher Hubert Dreyfus (1992), computer scientist Terry Winograd (Winograd and Flores, 1987; Winograd, 1996), and the social psychologist Donald Schön. In Europe, a similar push came from participatory designers (see Ehn, 1988a) and from Italians like Carlo Cipolla. For more contemporary criticisms and accounts, see Dorst (1997), Gedenryd (1998) and Dourish (2002).

5.Rorty (1967), Rabinow and Sullivan (1979). It is interesting to note that for many main proponents of rationalism like Simon, this philosophical critique was barely more than a form of religion, and therefore not worth replying to. Hunter Crowther-Heyck (2005, pp. 28–29 and 342, note 54) wrote in her biography of Herbert Simon how Simon, always eager to defend his views, had a prophet’s difficulty in understanding why some people did not get his message: “He wrote many a reply to his critics within political science, economics, and psychology, but he never directly addressed humanist critics of artificial intelligence, such as Hubert Dreyfus and Joseph Weizenbaum because ‘You don’t get very far arguing with a man about his religion, and these are essentially religious issues to the Dreyfuses and Weizenbaums of the world,’” as he wrote in his private letters.

7.1. Acting in the World

In his inaugural lecture at Technische Universiteit Eindhoven, Kees Overbeeke, leader of the Designing Quality Interaction research group, argued that design researchers overrate cognitive skills. His lecture told how dissatisfaction with cognitive psychology drove him to J.J. Gibson’s ecological psychology and more recently to phenomenological psychology and pragmatic philosophy. 6 His change of mind brought about an interest in people’s perceptual-motor, emotional, and social skills.

6.Interestingly, Norman sits in a pivotal position when it comes to the post-Cartesian turn. His scientific reputation was based in cognitive science, but he also popularized the notion of “affordance” from Gibson’s ecological psychology through his 1988 book on design. Admittedly, he interpreted Gibson through cognition, talking about “perceived affordances” rather than direct perception, as Djajadiningrat (1998, p. 32) and Djajadiningrat et al. (2002) have argued.

Meaning … emerges in interaction. Gibson’s theory resulted from a long line of “new” thinking in Western philosophy, i.e., Phenomenology (Merleau-Ponty, Heidegger) and American Pragmatism (James, Dewey)…. All these authors stress the importance of “acting-in-the-world,” or reflection being essentially reflection-in-action.7

7.Overbeeke (2007, p. 7).

In Overbeeke’s vision, engineering and design join theorists in the humanities and the social and behavioral sciences. In these fields, researchers have grown disillusioned with studying people as mechanisms that can be manipulated and measured.

Showroom has followed a similar course, but it draws from a still wider swath of theory. In addition to philosophy, psychology, and the social sciences, Showroom also builds on art and design. Anthony Dunne’s Hertzian Tales can be seen as a primary text for Showroom. 8 It offers a mesh of intersecting theories that is similar to the humanities of the 1990s. This text borrows from theories of post-modern consumption, phenomenology, French epistemology and semiotics, and product semantics. It also borrows from pragmatist philosophy, critical theory, and studies of material culture. 9 Italian controdesign, another important inspi-ration to critical design, built on post-war political sociology, urban studies, semiotics, and philosophy, as well as on futurists, Dada, surrealism, and pop art. There are few scattered references to scientific psychology in Hertzian Tales, but scientific literature is simply yet another inspiration for design.

8.Dunne (2005).

9.The main theorists were Jean Baudrillard in post-modernism and consumption, Paul Virilio in phenomenology, Gaston Bachelard in epistemology, Roland Barthes in semiotics, Klaus Krippendorff in product semantics, George Herbert Mead and John Dewey in pragmatism, Herbert Marcuse and Theodor Adorno in critical theory, and Arjun Appadurai and Daniel Miller in empirical research on material culture.

Field has arrived at the same destination by following a different route. Field researchers typically build on symbolic interactionism, symbolic anthropology, ethnomethodology, and Bruno Latour’s actor-network theory rather than philosophy. However, when seen in the context of twentieth century thinking, there are significant affinities to Lab and Showroom. For example, the symbolic interactionism movements came to Chicago in the first part of the twentieth century, and its founding fathers listened to the lectures of pragmatists like John Dewey and George Herbert Mead. These two movements have clearly been conceived in the same intellectual climate. 10 A similar argument applies to ethnomethodology. It has roots in sociological theory, not philosophy, but it shares many similarities with phenomenology. 11

10.Joas (1983).

11.Dourish (2002); for ethnomethodology, see Lynch (1993).

These post-Cartesian philosophies gained more currency in the last three decades of the twentieth century; first in the humanities, then in the social sciences, and more recently in technical fields. By building on these traditions, designers are able to respond to more design challenges than by building on rationalistic and cognitive models only. These traditions have led constructive design researchers to see cognitive psychology and rationalistic design methodologies as special cases of a far larger palette of human existence. Seen through this prism, an attempt to see humans as information processing machines is not wrong, only a small part of the story. Research has become interdisciplinary, with ingredients from design and technology, and also psychology, the social sciences, and the humanities. 12

12.Dourish (2002).

7.2. Lab: From Semantic Perception to Direct Action

As the earlier quote from Overbeeke’s inaugural lecture showed, recent work in Lab is interested in action and the body rather than thinking and knowing. Thinking and knowing are studied but from within action. Cognitive psychology has been pushed to the background; in the foreground are Gibson’s ecological psychology and recently, phenomenological philosophy. 13 Eindhoven’s Philip Ross makes a useful contrast between cognitive and ecological psychology and explains how they lead to different design approaches:

The semantic approach relies on the basic idea that we use our knowledge and experience to interpret the symbols and signsof products…. Products use metaphors in which the functionality and expression of the new product is compared to an existing concept or product that the user is familiar with. Emoticons in instant messenger applications are examples of emotionally expressive semantic interaction in the domain of on screen interaction.

The direct approach is action based. It is inspired by Gibson’s perception theory, which states that meaning is created through the interaction between person and the world…. Perception is action, which reminds us of the phenomenological concept of technological mediation…. It seems plausible that a device designed from the direct approach, which allows a person to actively create his own expression, would allow more emotional involvement. This approach would thus more likely allow a person to be meaningfully engaged with the activity of emotional self-expression and evoke an enchanting experience rather than a device that offers pre-created expressions.14

14.Ross et al. (2008, p. 361).

While traditional user interface design works with symbols and proceeds to use through knowledge, research on tangible interaction focuses on how people interact with physical objects. The direct approach begins with action and proceeds to use through tangible interfaces and seeks design inspiration from action. Designers need to identify patterns of action that feed users forward naturally without a need to stop and think, which requires cognitive effort (Figure 7.1).

|

| Figure 7.1 Two approaches used to create meaning in interaction design. 15 15.Djajadiningrat et al. (2002, p. 286). |

Philip Ross’ work illustrates how the direct approach can be turned into a design tool. While ethics is usually the realm of the clergy and philosophers, Ross turned ethics into a source of inspiration. Nine designer/researchers from industry and academia convened around this challenge for a one-day workshop at the Technische Universiteit Eindhoven in the Netherlands. 16 The participants first learned about five ethical systems, Confucianism, Kantian rationalism, vitalism, romanticism, and Nietzschean ethics. They were then broken into three groups, and each group was given the task of building two functionally similar products that had to be based on two different ethical perspectives.

For example, one team was assigned the challenge of making two candy vending machines, one embodying Kantian ethics and the other embodying romanticism. They describe the “Kantian” machine in the following way:

The “Kantian” machine presents itself through a split panel with buttons and sliders…. On the left side of the panel, a person “constitutes” candy by setting parameters like for example the amount of protein, carbon and fat…. After adjusting the parameters, the machine advises a person to proceed or not, depending on his or her fat index…. After weighing the advice, the person proceeds to the right side of the panel. The machine asks for a credit card and determines whether the buyer’s financial situation allows the purchase. If so, the machine deposits a round piece of candy with the requested constitution in the slot on the bottom right.17

17.Ross et al. (2008, pp. 364–365). This simple workshop shows that many of the systems we engage in today channel Kant's strict, protestant, rationalistic ethic based on the idea of duty. Today you can even witness an increasing number of mobile applications that follow this line of thinking, helping people to track the details of their consumption including fat, carbohydrates, protein, etc. You can also see mobile tools like www.mint.com, which monitors electronic purchases, tracks personal finances, and visualizes how this impacts a user’s explicitly set saving goals. It is not hard to then imagine a machine that begins to integrate these two streams and functions as a decision support tool in the way the workshop designers imagined.

The Romantic machine, in contrast, displays dramatic emotions and incorporates elegant, grand gestures to treat people as sensuous beings. Its form language was non-utilitarian, it unleashed sugary aromas, it built anticipation through a slowed delivery of the desired product while using dramatic movements, and it required dramatic gestures before it accepted payment. While it is easy to see connections to the Kantian machine in many of the products and services people interact with every day, traces of the Romantic machine are harder to find. These romantic interactions, however, flourish in luxury spas, cruise ships, restaurants, and amusement parks (Figure 7.2).

As these workshops demonstrate, lab researchers in Eindhoven have turned away from semantics and symbols to direct action and beyond. They showed how design researchers can draw on highly abstract philosophy to spot design opportunities and process them into systems and objects. This work also asks a number of questions about implicit values in design, such as the hidden Kantian assumptions in so many products.

7.3. Field: You Cannot Live Alone

The approach of researchers in the field builds on theories of social interaction from psychology, sociology, and anthropology. This shift leads to a significant change in design. Cognitive psychology focused on the thinking process of an individual, and this was also true of Gibson’s ecological psychology and Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology. 18 When field researchers began to study social action, they provided an important remedy for this individualistic tendency. People listen to other people, influence them, pay attention to things others see as important, and mold their opinions on things like ethics based on these social influences. Neglecting this social substratum is a risk for any ambitious researcher.

18.For example, Lynch (1993, pp. 128–129).

Designers and design researchers have always been able to bring social context into design. Many work with scenarios and storyboards that bring the context and the stories of people back into the ideation process. Interaction designers, in particular, have always worked this way. Their goal is to define the behavior of a product — generally a sequence of action and reaction that can best be captured in a narrative structure. They create characters who live in the context of use, and then they generate many stories about these characters in order to imagine new products and product behaviors that improve the characters’ lives. Over the past few years, interaction design has increasingly focused on the social aspects of interaction: how products and services mediate communication between people. 19 However, unless these narrative methods are grounded in real data, they easily reflect only the wants and preferences of researchers. At worst, they become just devices of persuasion.

19.Forlizzi (2007).

In contrast, field researchers have built on many kinds of sociological and anthropological theories to study people properly. The most popular theories in the field approach have come from symbolic interactionism, ethnomethodology, and symbolic anthropology. Interactionists describe how people define situations in order to take action, while ethnomethodologists describe “folk methods” (ingrained scripts of social behaviors) people use in organizing their activities. 20 Symbolic anthropologists, on the other hand, study how large systems of meaning play a part in what people do and how they think. Examples of such large systems are religion and beliefs about family (Figure 7.3).

20.Ethnomethodologists talk about “ethnomethods,” meaning those methodic procedures people use to organize their ordinary activities. The classic statement is Garfinkel (1967); a particularly clear exposition is Livingston (1987).

One example of interactionist thinking is Battarbee’s work on user experience as a social process. 21 Her work builds on the pragmatist look (from Jodi Forlizzi and Shannon Ford) on how some things become noticeable and memorable. People bring emotions, values, and cognitive models into hearing, seeing, touching, and interpreting the influence of artifacts. Social, cultural, and organizational behavior patterns shape how things are picked up from “subconscious” experience. 22 In contrast to the work of Forlizzi and Ford, for Battarbee, experience is a social process — hence, “co-experience” — for Battarbee. When people interact, they bring attention to issues, insights, and observations. In paying attention to things, and people make these things noticeable and sometimes memorable. Some things, on the other hand, are forgotten and pushed into the background.

22.Forlizzi and Ford (2000, p. 420).

Battarbee constructed her thinking during research on mobile multimedia. The path from a mere background possibility to an experience is social. She showed how communication technology can mediate this process. She investigated mobile multimedia in a real social context, focused on actual messages, and observed how people together pick up things and push them away from attention. Her work linked field observations with social theory. She also showed how designers can use these theories to generate design insights for new multimedia services.

Symbolic interactionism and ethnomethodology have their roots in sociology, but both traditions are distant relatives to the same philosophical traditions from which Lab seeks inspiration. Namely, symbolic interactionism came of age in the years between the World Wars in Chicago where an intellectual milieu shaped by the pragmatist John Dewey and the social behaviorist George Herbert Mead was created, and ethnomethodology had many affinities with phenomenology. It is important to understand, however, that these writers are not forefathers of these sociological traditions, which built on many other strands of thinking.

7.4. Showroom: Design and Culture Under Attack

Critical design focuses its attention on even larger things in society than field researchers. Its target of criticism is the way in which design supports consumer culture. Critical designers do not specify who they specifically blame and do not offer an alternative lifestyle. In this sense, research artifacts produced by critical designers are laden with many kinds of assumptions; viewers have to rely on their own background of culture, arts, and design to understand it. They have to make connections between the many theoretical perspectives at play to construct a rich understanding of this work.

In the preface to Hertzian Tales, Anthony Dunne told how “design can be used as a critical medium for reflecting on the cultural, social, and ethical impact of technology.”23 The basic objects of criticism are commercially motivated and human factor driven approaches at work in electronics; it is these electronics most people assimilate into their lives without thinking about how these objects shape their lives. In the preface to the 2004 edition of Hertzian Tales, Dunne looks back at 1999 when the book first appeared in print. He noted that little had changed in the design of electronics despite many calls for more creativity:

23.Forlizzi and Ford (2000, p. 420).

It is interesting to look back and think about the technological developments since [1999]. Bluetooth, 3G phones, and wi-fi arenow part of everyday life. The dot-com boom has come and gone…. Yet very little has changed in the world of design. Electronic technologies are still dealt with on a purely aesthetic level. There are some exceptions, of course … but still, something is missing. Design is not engaging with the social, cultural, and ethical implications of the technologies it makes so sexy and consumable.24

24.Dunne (2004, p. xi).

The critical design method builds prototypes and other artifacts based on “familiar images and clichés rather than stretching design language.”25 These designers investigate the metaphysics, poetry, and aesthetics of everyday objects to create designs that are strange and invite people to reflect on these qualities. 26

25.Dunne (2005, p. 30).

26.Hertzian Tales distinguishes several classes of objects. “Post-optimal objects” provide people with new experiences of everyday life; “parafunctional” questions the link between prevailing aesthetics and functionality; while “infra-ordinary” objects to change concepts and probes how designers could author new behavioral and narrative opportunities. See Dunne (2005, p. 20).

The most difficult challenges for designers of electronic objects now lie not in technical and semiotic functionality, where optimal levels of performance are already attainable, but in the realms of metaphysics, poetry and aesthetics, where little research has been carried out.27

27.Dunne (2005, p. 20).

Clearly, this is an attack against the prevailing culture of design. But who are the “designers” under attack?

The answer lies in the theoretical background of critical design. As noted earlier, critical design builds on a wide array of sources. The main theoretical roots of critical design, however, can be found from twentieth century philosophy, humanities, and the social sciences. The original formulations of critical design borrowed heavily from post-structuralism, critical theory, post-Marxist interpretations of the material world, Italian radical design, and many kinds of avant-garde and contemporary art. 28 Some of the key targets of these writers were consumption, art, and everyday life. In particular, the all-pervasive media continually bombards people with images of art for commercial and political purposes. This seemingly endless cascade of images and sounds re-shapes people’s desires, and it changes the processes and motives for the products and services that are made. 29 If designers build on this language of consumptive desire without trying to redirect it, they function like Hollywood film studios, looking for blockbusters and lucrative product tie-ins (Figure 7.4).

28.This is not to imply that critical design is somehow Marxist. Dunne (2005, p. 83) distanced himself from Marxism and wrote: “Many issues touched on here, such as … the need for art to resist easy assimilation, overlap with those already addressed by the Frankfurt School and others…. The similarities between these issues and those addressed by Marxist approaches to aesthetics do not imply an identification with Marxism but are the result of seeing design as having value outside the marketplace — an alternative to fine art.”

29.As the situationists noted, this mediascape is pervasive enough to be taken for reality (Debord, 2002). This was later one of the pet ideas of French philosopher Jean Baudrillard. As Chapter 6 showed, the situationists are particularly relevant to design through the early days of critical design and also to HCI through Bill Gaver’s work.

Such a culture of design goes beyond individuals and design institutions. For this reason, it makes little sense to directly criticize individual designers, design schools, or design firms. The proper place for criticism is language and visual culture, not any particular designer. To make critique meaningful, it has to be directed at what makes this culture possible — otherwise it becomes trapped within the same discourse. As always, stepping out of this culture is impossible. However, it is possible to work from within and create designs that extend the clichés and easy seductions into mainstream design.

There is considerable theoretical depth in critical design. The target of criticism is the very culture of design-as-usual. No one in particular is to blame: it is the background that makes this culture possible that needs to be questioned. Again, this is a premise that comes from Continental thinking. 30 Post-structuralists like Jean Baudrillard taught critical designers to focus on gaps in design practice, to seek ways to break it one small piece at a time. Practices like design are human achievements, but we tend to take them for granted, regardless of their historical character. Indeed, why not treat design the same way as philosophers Jacques Derrida treated literature and Michel Foucault treated the history of sexuality? Although theoretical references have largely dropped from critical design over its 15 years of existence, this background is still evident in its practices, aims, and critical ethos.

30.In particular, Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault. This book is not a place to open conversation about their oeuvre. Readers are encouraged to read their original work.

7.5. Frameworks and Theories

A rich array of theory gives constructive design research plenty of depth. It helps to raise interesting questions about ethics in design. It helps to see things like social interaction. It creates connections to other disciplines and forms of culture, deepening research and design. Finally, it also gives research consistency and a possibility to argue.

The question, then, is not whether theory is useful, but how should it be used. Design is not a theoretical discipline. Designers are trained to do things and are held accountable for producing stuff, to paraphrase the title of Harvey Molotch’s book on design. 31 Designers are not trained to do product concepts and theories, nor are they held accountable for producing these abstract things. With few possible exceptions, design researchers have produced little theory that is used in other disciplines. 32

31.Molotch (2003).

32.Leading candidates for such theorists are Tomás Maldonado and Klaus Krippendorff.

To see how constructive design researchers use theory, it is useful to start from the frontline of research. The first frontline is design. In this book, we have seen several designs from product-like designs Home Health Horoscope and Erratic Radio. We have also seen artistic works like Symbiots. There are also service prototypes like Nutrire Milano and public interest prototypes like Vila Rosário. Researchers put most of their effort into developing designs and prototypes.

Also frontline are the frameworks that are generalized from these designs, such as Jodi Forlizzi’s product ecology, Caroline Hummels’ resonant interaction, and Katja Battarbee’s co-experience. 33 Typically, these frameworks are reflections that come after designs. Their ingredients are theories, debates, and the design process. If design researchers want to contribute to theory, this is where they place their effort. Also, this is where constructive design researchers contribute to human knowledge at large. The best way to learn about how people interact with tangible technology is to read research coming from places like Eindhoven, Delft, and Carnegie Mellon University. The best way to see how to design large-scale services is to read work coming from Milan.

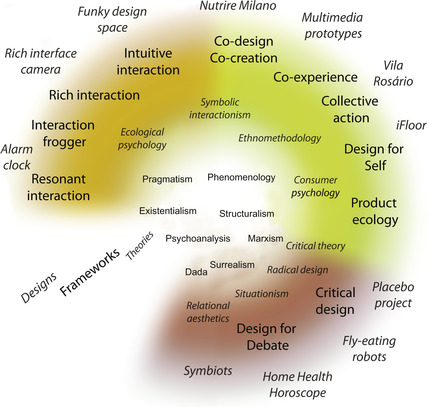

Even more abstract theoretical thinking keeps research programs going for years, creating consistency behind designs and frameworks. For example, J.J. Gibson’s ecological psychology has been a constant source of inspiration in Eindhoven. To see how Tom Djajadiningrat’s cubby, Stephan Wensveen’s interaction frogger, Joep Frens’ rich interaction, and Andres Lucero’s intuitive interaction are related, it is necessary to read Gibson. 34 Symbolic interactionism has played a similar role in Helsinki, and situationism and controdesign in London. These references are abstract and as such, difficult to turn into design. Typically, they appear only in theoretical sections of doctoral theses and occasionally in conference papers. Constructive design researchers build on them but practically never hope to add to this knowledge. Martin Ludvigsen’s collective action framework is built on Erving Goffman’s sociology, but Goffman’s theory is in no way tested by Ludvigsen. 35

35.Ludvigsen (2006).

Explicit references to theory typically stop here. However, people like Gibson and the situationists have had their predecessors. Tracing back to these predecessors connects constructive design research with the most important philosophical and artistic movements of the twentieth century. These movements include phenomenology, pragmatism, Ludwig Wittgenstein’s late philosophy, and also several artistic movements like Dada and surrealism, and through these, to existentialism and psychoanalysis. For example, in Field, these movements go back to pragmatism and phenomenology, and in Showroom to psychoanalysis, structuralism, and phenomenology (Figure 7.5).

In actual research, these philosophies and artistic movements remain in the background. Typically, only senior professors know the whole gamut. Even they seldom go to theoretical and philosophical discussions, and always cautiously, when rethinking something at the very foundation of the program. Knowing that some issues can be left to senior researchers makes life easier for younger researchers. Also, there are few direct links between philosophical and artistic thinking and actual designs. Going all the way to philosophy may even distract researchers. If a researcher wakes up every morning thinking that he must make a theoretical breakthrough, he fails, daily. There is no specificity in design research if it only focuses on philosophy: theoretical work is valuable but so is design and the creation of frameworks.

Although it may seem that constructive design researchers all have their own agenda, they converge at many points. Post-Cartesian philosophical and artistic approaches provide space for investigating materials, issues, and topics. 36 Among these issues and topics are things like the body, social action, or those unquestioned assumptions about “normality” that critical designers question. 37 Perhaps most important, these background philosophies and artistic traditions open doors for putting design into the center of research. Theory has a role in explicating why design works, but it does not tell how to create good design. This background, finally, explains why current constructive research looks so different from the rationalism of the 1960s — it comes from a different mental landscape.

36.Including the leading writers from Ulm, like Otl Aicher (2009) and Tomás Maldonado (1972).

37.For example, see Overbeeke and Wensveen (2003, p. 96).

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.