5. Field

How to Follow Design Through Society

While Lab decontextualizes, another set of successful research practices takes the opposite approach and puts design in the real world. Our example of how design can be used in the real world comes from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where Marcelo and Andrea Júdice created a series of low-tech designs to improve public health in Vila Rosário, an impoverished village in metropolitan Rio de Janeiro. In their work, design is informed and created by going out of the studio and the workshop into the real world. Field studies can be done at every phase of the design process. Concepts and prototypes become things to be followed rather than tested. Researchers observe what happens to design ideas in the real world, create interpretations of their observations, and use these interpretations to take further steps in design. Although designers like the Júdices borrow from social science, they treat field research as a source of ideas for design.

Many design researchers have borrowed their methods from interpretive social science rather than experimental research. If there is one keyword to describe the field approach to design, it must be “context.”1 Field researchers work with context in an opposite way from researchers in a lab. Rather than bringing things of interest into the lab for experimental studies, field researchers go after these things in natural settings, that is, in a place where some part of a design is supposed to be used. Researchers follow what happens to design in that context. They are interested in how people and communities understand things around designs, make sense of them, talk about them, and live with them. The lab decontextualizes; the field contextualizes.

1.See Wasson (2000, pp. 377–378).

Field researchers believe that to study humans and their use of design they need to understand their system of meanings. Studying humans and studying nature differ in a crucial way because of these meanings. Simply, people make sense of things and their meaning and act accordingly. An apple falling from the tree does not care about the concept of gravity and cannot choose what to do. When the president declares war, he certainly knows what he is doing with his words and knows he has alternatives. 2 Even when people do something out of habit, they are selecting from alternatives and may always change their ways. 3 If researchers see society in these terms, they also think that searching laws that could explain human activity and society is misguided. Instead, they take even the goofiest ideas seriously if they shape human activities.

2Winch (2008, p. 119).

3Winch (2008, pp. 86–87).

Design ethnography differs from corporate ethnography, an heir of studies in organizational culture, which focused on issues like management and how symbols integrate organizations. Design ethnography works with product design and is a way to handle cultural risks in industry. 4 Sometimes it is a separate front-end activity, and sometimes it is closely integrated into product development. Design ethnographers typically work in teams and use prototypes during fieldwork to create dialog with the people in the study. They communicate through formats accessible to engineers, and their fieldwork is measured in days or weeks, not months. For them, first-hand experience of context is typically more important than fact finding or even careful theoretically informed interpretation. 5 In this chapter, we use “design ethnography” and “field work” interchangeably.

5For some of these research practices, see Nafus and Anderson (2010). This synopsis is based on Koskinen’s discussion with Ken Anderson, a veteran of design ethnography and the founder of the EPIC conference, Hillsboro, Oregon, August 19, 2010.

5.1. Vila Rosário: Reframing Public Health in a Favela

Vila Rosário is a design project in a former village that is now a part of the vast metropolis of Rio de Janeiro. It is located about 15 kilometers north of the famous towns Corcovado, Ipanema, and Copacabana. Even though it is not among the poorest of Rio’s areas, Vila Rosário is still a world apart from the glory of these famous neighborhoods (Figure 5.1). Its illiteracy rate is around 50%, sanitation is poor, and the poverty level is high. It suffers from high infant mortality and a high incidence of diarrhea, tuberculosis, and many tropical diseases, including yellow fever.

This was the playing field of two designers, Marcelo and Andrea Júdice, who set out to study the neighborhood and create designs that would improve the town’s public health. Initially, they were to introduce information technology into the village to improve the general living conditions of the inhabitants. However, after the first field studies, it became clear that it would not be a solution without considerable rethinking of the context. How could information technology help people who cannot read in a place where it is common to steal electricity?

The study began with cultural probes consisting of cameras, letters, diaries, and several tasks for volunteer health agents working in Vila Rosário. 6 After seeing the probe returns, the researchers realized that any attempt to make sense of Vila Rosário without visiting it would compromise a study aimed at improving health. So the researchers went to the village to do fieldwork and conduct a series of workshops with the locals to make sure they understood the probe results.

The study results identified hygiene and early diagnosis of tuberculosis as the main targets of design. Since it was beyond the means of the project to improve hygiene, the Júdices focused on improving awareness about the significance of hygiene, especially among children. The design hypothesis that evolved was based on this result. It became a combination of an IT-based information system and a low-tech approach. The aims were to raise awareness of how health and behavior are linked and to induce behavioral change among children and teenagers.

Design was started by creating a telenovela-like make-believe world with characters recognizable to the inhabitants in Vila Rosário. It was thought that these characters and their actions would stay in the minds of people better than mere health-related information. This world of characters had various types of individuals and families. Also, it had various types of professionals significant in terms of health, including doctors, nurses, nuns, and health agents. It did not, however, have characters like politicians, police, and gang leaders. The world reflected everyday life in Vila Rosário rather than its institutions, which locals did not trust (except the church and doctors).

Computers were pushed into the background. Essentially, IT became a Web connection helping nuns and local health agents (who are like paramedics, with some training in health care) to contact medical experts. Computers were placed in a local health clinic, Institute Vila Rosário, run by the church, which became the hub of the study.

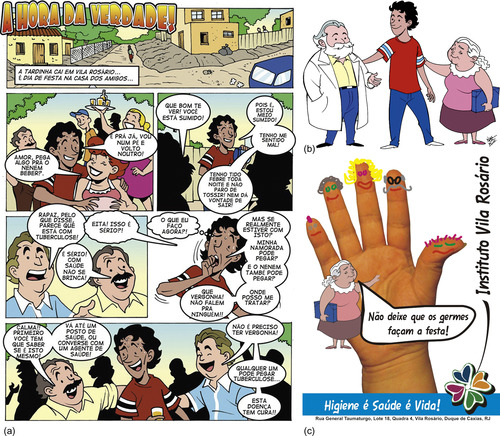

The main effort was to put low-tech designs like comics describing safe ways to use water and cooking utensils (Figure 5.2). Other designs were posters pointing out key facts about hygiene, such as the importance of cleaning fingernails and kitchen knives, and there were also stories for children. The characters in these stories showed what happens to people who do not practice proper hygiene and do not see a doctor when they have symptoms of illnesses like tuberculosis. In addition, researchers created an identity for the program consisting of a series of accessories and company gift-like designs, such as folders, bags, and T-shirts. These were created to make the design program easy to identify and remember.

All these designs were cheap, colorful, relatively easy to produce, and did not produce anything valuable that could be stolen and sold on the black market. Furthermore, these designs fit into the social structure and cultural understandings of Vila Rosário. They were based on the probe returns as well as on ethnographic understanding. These sources provided the designers with a necessary understanding of themes important in Vila Rosário, which provided the information to create a local look and feel to the designs. The materials were produced locally, and distributed in Vila Rosário through health agents.

The designs were evaluated in three ways. In Vila Rosário, all of the main designs were evaluated with a variety of local participants in workshops. The focus was on whether people understood the design and whether they were enticing enough to produce. In Helsinki, a Brazilian expert specializing in public health in the tropics evaluated the design proposals. In this evaluation, the focus was on factual content and understanding the health care structure of the village. Finally, the design process was replicated in a two-week workshop in Namibia. Here, the question was whether it is possible to scale down the method developed in the study so that it could be used outside Rio de Janeiro (Figure 5.3).

The Vila Rosário study showed how a serious commitment to context may lead to a major redefinition of a design effort and how this commitment changed design from a technical exercise to a low-tech one. It also showed the importance of understanding the context in detail. The designs generated knowledge about the visible and material culture of the Vila as well as about its habits, beliefs, and social structures. When it comes to design ethics, the study showed serious commitment to poor people who do not usually get to enjoy good design. In terms of design research, it also led to questioning many first-world assumptions; for example, how can probe studies be done when people cannot read?

5.2. Understanding as the Basis of Design

Field research entered industry in the late 1970s and early 1980s mostly as a response to changes in computing. 7 In essence, it was a response to a failed case. When computers moved from universities, research institutes, and major corporations to homes and offices, users could not understand how these machines worked. The failure was obvious, but prevailing systems design methods were not able to explain why.

7For example, see Hackos and Redish (1998).

In response, researchers started to do fieldwork to see how computers were used in ordinary circumstances. This orientation primarily took place in countries with strong computer industries, with Silicon Valley leading the way. Field research proved to be especially useful for industry in the early phases of product design when requirements are specified. As design anthropologist Christine Wasson noted, “by 1997, every major design firm claimed to include ethnography as one of its approaches.”8

8Wasson (2000, p. 382).

This was certainly the case in Silicon Valley. 9 In the Valley’s IT industries, ethnographic research was a response to the need to understand not only how people could use computers but also what they wanted from computing. Contextual design, in particular, became a business success. 10

9For example, see Wixon and Ramey’s (1996) collection. See Tunstall (2008). The Ethnographic Praxis in Industry conference occurred in 2005, providing a meeting point for the community. See Wasson (2000, pp. 384–385), Jordan and Yamauchi (2008), Jordan and Lambert (2009), Squires and Byrne (2002) and Cefkin (2010).

10See Beyer and Holtzblatt (1998). For a guide to fieldwork based loosely on ethnomethodology, see Randall et al. (2007).

Silicon Valley also gave birth to a more design-led approach to fieldwork. Researchers like Jane Fulton Suri and Alison Black at IDEO and Liz Sanders at Richardson/Smith pushed designers out into the field to see what people do in real life. 11 The idea was to get designers out of the studio to bond with people and to focus on what they do rather than on what they say. 12 For skilled designers, insights drawn from observations are based on years of experience. Fulton Suri discussed about how a few successful designers do fieldwork:

11Fulton Suri still works at IDEO, but Black has her own agency in Reading, near London. Richardson/Smith was bought by Fitch, which Sanders left to set up SonicRim in 1999.

12Segal and Fulton Suri (1997) and Black (1998). Perhaps the best example of such work is Fulton Suri’s book Thoughtless Acts? Observations on Intuitive Design (Fulton Suri and IDEO, 2005), which consists of photographs of people’s own design solutions without captions, and a short text that explains the intentions of the book. This text is at the end of the book and is meant to be read after watching the images because, as Fulton Suri noted, life comes without captions.

Certainly ethnographic-style observation can provide inspiration and grounding for innovation and design. It increases our confidence that ideas will be culturally relevant, respond to real needs and hence be more likely to have the desired social or market impact. But for design and designers there’s much more to observation than that…. Successful designers are keenly sensitive to particular aspects of what’s going on around them and these observations inform and inspire their work, often in subtle ways. Firsthand exposure to people, places, and things seems to be key, but there is no formulaic method for observation of this very personal kind….

But their approach was certainly not without discipline or rigor. Each case involved a similar pattern: a focused curiosity coupled with exposure to relevant contexts, attention to elements that invited intrigue, visual documentation and revisiting these records later, percolation and talking about what was significant with team members and clients, and storytelling and exploration of design choices and details. 13

This kind of research goes far beyond tourist-like observation; it gains understanding of what goes on in people’s minds in some instances. It also goes beyond mere analysis. Making a systematic description of data is a step in the process of gaining an empathic grasp, but research does not stop there. Good design research is driven by understanding rather than data (Figure 5.4).

Somewhere between these orientations were other earlier practices, such as in the Doblin group and later E-Lab. 14 Participatory design was a Scandinavian amalgam of computer science, design, sociology, and labor union politics. 15 It sought to battle deskilling, which the Marxist labor theorist Harry Braverman saw as the main aim of management in his book Labor and Monopoly Capital. 16 Instead of making workers replaceable by machines, participatory designers sought to empower workers. 17

14E-Lab was bought by Sapient in 1999.

15See especially Ehn (1988a) who offers a first-hand account of participatory design, although years after the work was done. Also Greenbaum and Kyng (1991) and Schuler and Namioka (2009).

16Braverman (1974). For example, Ehn (1988a) and Greenbaum and Kyng (1991). Some participatory designers flirted with activity theory, but this movement has no shared theoretical basis. See Kuutti (1996), Bødker (1987), Bødker and Greenbaum (1988), and Kaptelinin and Nardi (2009).

17See especially Ehn (1998a).

5.3. Exploring Context with Props

Field research methods in design are immediately recognizable to professional social scientists. They are also often taught to designers by social scientists. Still, design ethnography differs from ethnography as it is practiced in anthropology and its sister disciplines. 18 If there is something specific in design fieldwork, it is probably the focus on products and things and the use of mock-ups and prototypes.19 Even more differences exist when design begins. Designers’ analytic methods range from brainstorming techniques and future workshops to such co-design tools as “magic things,” design games, video sketching, and using Legos to simulate products, interactions, and organizations. 20

18Good and practical descriptions of fieldwork in design are Blomberg et al. (2009) and, for contextual inquiry, Holtzblatt and Jones (2009).

19For a good example of systematic attention to products in fieldwork, see Jodi Forlizzi’s (2007) work on the Roomba in senior citizens’ homes.

20For generative tools, see Sanders (2000), Stappers and Sanders (2003) and Sleeswijk Visser (2009). Magic Things are the brainchild of Iacucci et al. (2000), a good source for designing games is Brandt (2001) and a place to look at using video in design is Ylirisku and Buur (2007). A future workshop is from Jungk and Müllert (1983).

We put a large number of components together into “toolkits.” People select from the components in order to create “artifacts” that express their thoughts, feelings and/or ideas. The resulting artifacts may be in the form of collages, maps, stories, plans, and/or memories. The stuff that dreams are made of is often difficult to express in words but may be imaginable as pictures in your head.21

The aim is to turn fieldwork into an exercise of imagination rather than mere data gathering. In the tough time lines of design, it is hard to view “dreams” by observation alone. If researchers want to learn about things like dreams, people have to be invited to the dream during fieldwork. Sensitizers like Dream Kits are useful for this reason as they function to elicit people’s projective fantasies.

For example, from 2008 to 2010, researchers from the Danish School of Design built a model to show how anthropology could be used in design. This model was developed in a book focusing on reducing garbage incineration in Copenhagen. The editor, Joachim Halse, opens the book by calling it a manifesto, stressing its political nature. For him, the book offers a participatory approach for creating design opportunities that evolve around life experiences. The spirit of the study was to lower the line between anthropological fieldwork and design, but there were other drivers as well. One driver was developed to get more and more diverse people involved in the process. In DAIM, shorthand for Design Anthropology Innovation Model, the researchers used mock-ups, acted out scenes, organized design games and workshops, and rehearsed service scenarios with people (Figure 5.5).

5.4. Generating Concepts as Analysis

One problem spot in fieldwork has been explaining synthesis — how design ideas emerge from fieldwork. Synthesis is a creative mash of common sense and research and stresses design opportunities rather than theory. This argument, however, puzzles non-designers, to whom this sounds mystical, to say the least. However, even though most designers avoid references to the social sciences, their methods are systematic.

Broadly speaking, there are two types of approaches that deal with synthesis. Some researchers borrow heavily from the social sciences. They search models from analytic induction, grounded theory, and thick description in symbolic anthropology. 22 Christine Wasson tells how at E-Lab ethnographic data were analyzed from instances of data into patterns. These patterns were then turned into a model that interpreted ethnographic materials and envisioned a solution for the client.

22For analytic induction, see Seale (1999) and for its application in design, see Koskinen (2003) and Koskinen et al. (2006).“Thick description” is how Clifford Geertz, the dean of American anthropologists, described how anthropologists try to unravel “complex conceptual structures … knotted into one another … that are at once strange, irregular, and inexplicit.” Society is spaghetti, and the researcher’s job is to do “thick descriptions” to make it understandable (Geertz, 1973).There is no shortage of good books on ethnography and fieldwork in the social sciences. To list a few, one can mention Lofland (1976) for fieldwork, Emerson et al. (1995) for writing field notes, Becker (1970) for a wide-ranging discussion on fieldwork and its problems, and Seale (1999) for analysis and quality control. The so-called Grounded Theory by Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss has found its way into design more slowly than into fields like education (Glaser and Strauss, 1967; Strauss, 1987). If one builds on this “theory,” one gets instructions on how to build an abstract framework from observations, but there is a price. Unwary reliance on it leads to theoretical commitments: the process relies heavily on symbolic interactionism (see Blumer, 1969). This same remark also applies to contextual inquiry, where the commitments go to work flow models rather than theory (Beyer and Holtzblatt, 1998).

The model offered a coherent narrative about the world of user-product interactions: how a product was incorporated into consumers’ daily routines and what symbolic meanings it held for them. These insights, in turn, were framed to have clear implications for the client’s product development and marketing efforts.23

23Wasson (2000, pp. 383–384).

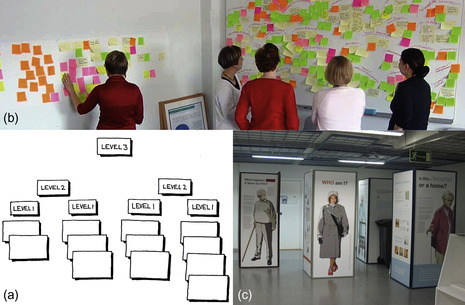

Most design researchers, however, avoid social science models altogether. They build on well-tried methods from design practice, including well-known models such as the workplace models and affinity diagrams in contextual inquiry and personas in software development (Figure 5.6).

|

| Figure 5.6 (a) How affinity walls generate abstractions. 24 (b) Using affinity diagrams to analyze data to generate design ideas. (c) personas in an exhibition in Kone Corporation, a lift and elevator maker. 25 24Holtzblatt and Jones (1990, p. 204). 25Mattelmäki et al. (2010). |

It is easy to add analysis to both procedures. If it is important to study gender, researchers simply analyze males and females separately and compare the results to see what kinds of differences exist. Adding age to this is also easy; researchers simply break the male and female groups into older and younger categories.

There are many overlaps between these two families; for example, working through data using affinity diagrams shares its underlying logic with analytic induction. Still, analytic induction is not always easy. Reflecting on her experiences on teaching ethnography in corporate settings, Brigitte Jordan noted how teaching data collection is easy, but the lack of tradition in analysis complicates analysis in design firms. Social scientists learn the craft of analysis through years of education and fieldwork that are almost impossible to convey “to non-anthropologists during a brief training period.”26 Seen from the other side of the fence, social scientists also fail: designers need more than verbal data and references from social science literature. When designers work with data, they make references to products, conceptual designs, and other pieces of design research rather than theoretical work in the social sciences. 27

26Jordan and Yamauchi (2008).

27Aalto (1997), quoted in Pallasmaa (2009, p. 73).

Creating an Interpretation28

28See Koskinen (2003, pp. 62–64).

Most field researchers explicate patterns from fieldwork observations rather than analyze them statistically. This process does not have a mathematical basis but is systematic, and outsiders can inspect it to spot problems.

Practice

Practical designers have several terms for this process. The best known term is probably “affinity diagram.” These diagrams cluster similar observations into groups, whereas other observations are in different groups. These clusters are then named. Analysis proceeds by grouping these clusters into still more abstract clusters. This process generates an abstract interpretation of data, and it is used as a starting point for design. This is done with Post-it® notes and whiteboards.

Analytic Induction

Social scientists call this kind of process “analytic induction.” Just like affinity diagrams, analytic induction begins with observations with more abstract interpretation. The difference is that in analytic induction, researchers make sure that there are no negative cases that would question the interpretation. This interpretation may apply to other data; however, it is best treated as a separate question.

Parsimony

To provide clarity, researchers usually prefer interpretations that consist of only a few concepts. A good interpretation is parsimonious. This is known as “Occam’s Razor,” named after medieval philosopher Willem Occam. An interpretation that consists of 10 or 20 concepts is difficult to understand, remember, and communicate. Keeping Occam’s Razor in mind helps to control this problem. Affinity diagrams and analytic induction lead to parsimony.

As Wasson noted, the association between ethnography and anthropology is little recognized in design, and the word “anthropology” is almost never heard. 29 An obvious exception is academic research carried out in universities, where it occasionally infiltrates into industrial practice. In particular, ethnomethodology has found its way into many types of software, design, and interaction design conferences, journals, and books. 30

29Wasson (2000, p. 385). As design ethnography mainly contributes to design rather than theory, the mother disciplines in the social sciences question its value. For example, as Tunstall (2007) related, the American Anthropological Association was then debating whether design anthropology is a worthy cause, or whether such a profit-seeking enterprise should be excluded from the scientific community.

30In addition to researchers from Palo Alto Research Center, the most consistent ethnomethodologists writing about design have been former EuroPARC researchers Graham Button and Wes Sharrock and, later, Andy Crabtree (see Crabtree, 2004; Kurvinen, 2007). The Palo Alto Research Center has scaled down on ethnomethodology, but this work continues in several universities, mostly in the United Kingdom.

5.5. Evaluation Turns into Research: Following Imaginations in the Field

As the design anthropologist Dori Tunstall noted, any anthropologist studies the material world. 31 Constructive design researchers do this too; however, their interest is in a very special kind of make-believe world, which is partially their own creation. They introduce their design imaginations into the lives of people to be able to follow how these imaginations shape the activities, thoughts, and beliefs of these people. These imaginations are not treated as physical hypotheses like in laboratory studies; instead they are treated as a thing to be followed in context. 32

31Tunstall (2008). However, there is a line here, which is well illustrated by Shove et al. (2007), who argued that designers should buy into “practice theory,” as they called their approach. Their study shows how social scientists understand design: they focused on studying things that exist at homes and were content with it. Their study had no projective features, even though one of the editors of the book was a designer.

32From a systems perspective, Keiichi Sato usefully talks about the knowledge cycle between artifact development and user. In his model, artifact development process, use and context of use are in a loop in which knowledge of use and use context feed the design of the artifact, and the artifact (or service) and design knowledge embedded in the artifact feed use and shape context of use (Sato, 2009, pp. 30–31).

These imaginations can be almost anything, such as a bottle refunding machine made of cardboard, but typically they are prototypes33 as with Ianus Keller’s attempt to build a tangible system for creating and browsing collections of pictures. 34 This was also the case in the project Morphome, which took a critical look at the idea of proactive technology — of using data from sensors to predict where human action is heading and adjusting things such as light and room temperature. Since there was no such technology on the market in 2002 when the project started, Morphome built proactive systems and devices, installed these systems into homes, and interviewed and observed people who used them. 35 These imaginations can also go beyond prototypes. For example, Andres Lucero simulated interactive spaces with design games by using objects like Legos as a tangible means to make people imagine what it would be to work and live in such spaces. 36

33See Säde (2001).

35Koskinen et al. (2006), Mäyrä et al. (2006).

Sometimes complex technological systems are needed to study designers’ imaginations, as in two early studies of mobile multimedia phones, Mobile Image and Mobile Multimedia. In these studies, researchers in Helsinki followed how people sent multimedia messages by recording real messages. 37 A more recent example comes from Pittsburgh, where researchers have taken a service design approach to investigate service innovation for public services, in this case a transit service. Fieldwork with transit riders revealed that their greatest desire is to know when a bus will arrive at a stop. Commercial systems that provide this service cost tens of millions of dollars. So the researchers have taken a very literal approach to the idea of co-production of value. They have designed Tiramisu (means pick me up in Italian), a smart phone application that allows transit riders to share GPS traces while riding the bus. By combining the schedule from the transit service and GPS traces from a handful of riders, Tiramisu can generate real-time arrival predictions and make this available to riders over mobile phones or the web. In this design the riders literally make the service they desire. The researchers built a working system and initial field study indicates that riders will share traces and that these traces can produce accurate real-time predictions (Zimmerman et al., 2011).

To create proper conditions for using prototypes in research, some methodological decisions are needed. Esko Kurvinen argued with his colleagues that designers should place their imaginations into an ordinary social setting. They should also follow it in this setting using naturalistic research design and methods over a sufficient time span to allow social processes to develop. Kurvinen and his colleagues developed four guidelines for properly analyzing prototypes and other expressions as social objects.

2. Naturalistic research design and methods. People have to be the authors of their own experiences. They are involved as creative actors who can and will engage with available products that support them in their interests, their social interaction, and meaningful experiences. Data must be gathered and treated using empirical and up-to-date research methods.

3. Openness. The prototype should not be thought of as a laboratory experiment. The designer’s task is to observe and interpret how people use and explore the technology, not to force them to use it in predefined ways.

4. Sufficient time span. The prototype ought to be followed for at least a few weeks. If the study period is shorter, it is impossible to get an idea of how people explore and redefine it. 38

Designers usually prefer to work with rough models in order to not direct attention prematurely to design details. The last thing any designer wants is feedback focusing on surface features of the expression rather than the thinking behind it. Paradoxically, being too hi-tech and true to design leads to bad research and design.

5.6. Interpretations as Precedents

Field research has its roots in industry, where it primarily informs design. It has provided a solution to an important problem, understanding, and exploring social context. It has been useful, and it has turned into a standard operating procedure. Plainly, it is useful to know how people make sense of what they see and hear and how they choose what they do.

However, field researchers produce “local” understanding that describes the context that cannot be applied uncritically to other cases. It is also temporary rather than something long-standing. 39 This specificity makes it useful in industry, but it also raises the question of generalization, how to apply his knowledge to other cases.

39The expression of local knowledge is from the anthropologist Clifford Geertz (1983).

There are several ways to respond to the question of generalization. Often generalization is irrelevant. Every designer studies the masters, whose works are always unique. Benchmarking looks at the top, not the average. At the top, the number of cases is by definition small. Also, studying a negative case may teach a lot; for example, even the best designers and companies fail occasionally, and these failures may be just as informative as the successes. Often, research generalizes through a program; instead of trying to describe universally applicable knowledge, it is often more useful to study one culture at a time. Finally, focusing on unique cases encourages creativity. Methods like cultural probes, experience prototypes, bodystorming, Magic Things, and role-plays came from individual projects. 40 Cultural probes would not have been seen if researchers in London had relied on well-proven scientific methods.

40See Buchenau and Fulton Suri (2000), Iacucci et al. (2000) and the IDEO Card Pack.

There is also a bigger picture. There are well-known and respected fields of learning that build on case studies. These include history and the humanities, clinical medicine, law, case-based business schools, and many natural sciences. Most good designers, design firms, and design schools work through precedents. 41 Whenever designers are faced with new problems, they study patents and existing designs to learn their logic. As a designer’s stock of precedents grows, he is better able to respond to various demands, put problems quickly into context, and foresee problems. 42 Experienced designers know how to spot opportunities, because they know so much about existing products, materials, production techniques, trends, and human beings43 (Figure 5.7).

41Note that comparison to law cannot be taken literally. In law, precedents are not just aids to thinking but are binding. This is not the case in design, in which precedents in fact have to be surpassed. For this reason, Goldschmidt (1998) argued for discarding the notion of precedent and resorted to “reference” in her work on IT-based reasoning systems for architecture. However, as Lawson (2004, p. 96) noted, designers often refer to “whole or partial pieces of designs that the designer is aware of” as precedents. Like Lawson, we prefer to work with designers’ own language but remind the reader about not taking the legal analogy too seriously.

42Similar to Brian Lawson, a student of design cognition who notes about architecture, “one of the key objectives of design education is to expose young students to a veritable barrage of images and experiences upon which they can draw later for precedent” (Lawson, 2004, p. 96). For a discussion on references and precedents, see Goldschmidt (1998) and Lawson (2004).

5.7. Co-Design and New Objects

Field research has been an industrial success, and it is also alive and well academically. It flourishes in several niches and is done throughout the design industries in both big and small markets. There are people who build on the social sciences, collecting data carefully and processing it into “thick descriptions.”44 There are also people who stress the value of merely diving into society to gain an understanding of people for design. At advanced levels in design universities, it has become a default methodology: it is a conscious choice not to do any field-style research.

Over the past two years, some researchers in Northern Europe have started to talk about their craft as co-design or co-creation. 45 What is new here is that the design process is increasingly opened to people, whether stakeholders or users. When designers work as facilitators rather than detached observers, the last remnants of the idea that researchers ought to be detached, impartial observers — “flies on the wall” — disappear. What comes about is the idea that design is supposed to be an exploration people do together, and the design process should reflect that. Many designers doing fieldwork have taken this model to heart, sometimes making it increasingly difficult to draw a line between designers and non-designers. 46

45See Koskinen et al. (2003). Mattelmäki et al. (2010).

46Speed dating is a technique to quickly decide which design concept works best: Davidoff et al. (2007), Park and Zimmerman (2010) and Yoo et al. (2010). This technique was first invented in a project reported by Zimmerman et al. (2003). Dream Kits are from Liz Sanders. Bodystorming and experience prototyping are from IDEO; cf. Buchenau and Fulton Suri (2000).

During the past few years, several researchers have also turned to action research, where the goal is to use knowledge gained by studying a group or community in order to change it. Particularly significant work has been done in Milan in conjunction with companies and communities in Lombardy. The Milanese approach to research is characteristically locally rooted and action-oriented, aiming to change local communities rather than creating new products. Around 2000, researchers were trying to improve service systems and concepts. 47 A few years later, this research evolved into studying how service design could be used to dematerialize society to make it ecologically and socially sustainable. 48 In terms of attitude, current Italian researchers are well in line with the ethos that drove their teachers’ work but work far more methodically. 49 Also, researchers in Milan are learning from other parts of the world; for example, the best book about co-design is written in Italian. 50

47Pacenti and Sangiorgi (2010). For doctoral-level work coming from this work, see Pacenti (1998), Sangiorgi (2004) and Morelli (2006).

48For system-oriented work, see in particular Manzini et al. (2004) and Jégou and Joore, (2004); also Manzini and Jégou (2003). For a shift in unit of analysis, see Meroni (2007) and Meroni and Sangiorgi (2011).

49In particular, this goes for Ettore Sottsass, Jr. Penny Sparke (2006, p. 17) described his philosophy as a conscious antithesis to post-war modernism, which “in Sottsass’ view, ignored the ‘user.’ His emphasis of the role of the user as an active participant in the design process, rather than a passive consumer, lay at the core of his renewal of Modernism. To this end, he experimented with a number of ways of bringing users into the picture while avoiding transforming them into ‘consumers.’”

Prototyping Services

Nutrire Milano51

51Thanks to Anna Meroni, Giulia Simeone, and Francesca Rizzo who helped to write this inset. For philosophy behind Nutrire Milano, see Manzini (2008).

Maybe the best example of design tackling issues far larger than a product comes from Milan, Italy.

Under the leadership of Ezio Manzini and Anna Meroni at Politecnico di Milano, a service design group specializing in sustainability, studied the relationship between the city of Milan and Parco Sud, a vast agricultural area south of the city, for almost a decade. Combining three interests — sustainability, service design, and the Slow Food values (Slow Food is the main project promoter) — the group tried to create a business model that would keep alive small-scale food production in Parco Sud.

Manzini calls this approach “action research.” The researchers worked with people trying to understand their hopes, needs, and worries. This research-based understanding was turned into projects that support the Parco Sud community. The aim has always been a permanent change to a common good.

This research illustrates the importance of fieldwork for design. Researchers have gone into Parco Sud and Milan, studying things like supply chains. They have ventured into co-designing business models through visual service design techniques. They also created a service prototype. There is a lively market every third Saturday of the month in Milan. The hope is that this prototype lives on and can be replicated elsewhere. Researchers have also built digital services to support their concept and continued designing new services for food production, provision, and consumption.

Key researchers in the group have mostly been trained in engineering, usability, and user studies. It is clear that in this study researchers had to work in the real world with people who have real problems and agendas. In trying to design viable business models, researchers do not have the luxury of going into a laboratory to build a model of research.

Through these developments, the designer’s interest is shifting from individuals and systems to groups and communities. There is also a trend away from products, experiences, and even services toward communities and large-scale urban problems. Although field methodology has proved its value in product development, it is still expanding and finding new uses and opening up new kinds of design opportunities.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.