6. Showroom

Research Meets Design and Art

Some constructive design researchers turn to art and design rather than the sciences or even the social sciences in search for methodology. The foundational work comes from London, where a group of researchers built a research program in the 1990s based on movements like situationism, Dada, surrealism, Italian controdesign, and critical theory. Recent work has sought inspiration from places like contemporary photography, Ludwig Wittgenstein’s late philosophy, and Bruno Latour’s writings. In this work, which we call Showroom following Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby’s book Design Noir, scientific research practices are redefined radically. For instance, instead of seeing articles as the main way to communicate, researchers prefer to show their work in exhibitions, where they can explore the borderline of contemporary art, design, and research. Designs become devices for debate and discourse rather than a series of hypotheses, as in Lab, or objects to be observed, as in Field.

The program we call ‘Showroom’ builds on art and design rather than on science or on the social sciences. When reading the early texts about research programs regarding showrooms, we were struck by critical references to scientific methodology. There is little respect for notions such as data and analysis, and it is possible to encounter outright hostility toward many scientific practices. Research is presented in shop windows, exhibitions, and galleries rather than in books or conference papers. Still, a good deal of the early work was published at scientific venues, most notably human–computer interaction (HCI). This work was aimed at reforming research, which it did to an extent.

Contemporary artistic practice is beyond the limits of this book, but it is worth noting that art went through many radical changes in the past century. While traditionally, art largely respected boundaries between painting and plastic arts, performing arts, and architecture, the twentieth century broke most of these boundaries. Contemporary art has also broken boundaries between art and institutions like politics, science, and technology. Although painting still dominates the media and the commercial art market, art has increasingly become immaterial, first exploring action under notions like happenings and performances, and then turning human relations into material. 1 With predictable counter-movements calling forth the return to, say, painting, art has moved out from the gallery and into the world at large (see Figure 6.1). 2

1.For a definition, see Bourriaud (2002). For an influential review, see Kester (2004). Bishop (2004, p. 62) lists as key sources Walter Benjamin’s “Author as Producer,” Roland Barthes’ “Death of the Author,” and Umberto Eco’s The Open Work.

2.For example, see O’Doherty (1986).

Design has had its own radical movements. 3 Radical Italian designers of the 1960s and 1970s turned to art to create a contemporary interpretation of society. Thus, the Florentine group of Superstudio proposed cubic spaces that allowed the youth to wander in the city and claim possession of the city space. 4 Similarly, the Memphis movement from Milan changed design by turning to the suburbs for inspiration. They found traditional furniture, cheap materials, neon colors, and cheesy patterns and built designs that challenged the high-brow aesthetic of modernism. 5 Designers like Jurgen Bey and Martí Guixé, 6 and groups like Droog carry the spirit to the present. 7

3.John Thackara (1988, p. 21) once argued that “because product design is thoroughly integrated in capitalist production, it is bereft of an independent critical tradition on which to base an alternative.” Design has had more than a few critical phases that have gained quite a following, including Victor Papanek’s writings about ecology in the 1960s, and Italian radical design movements. Anti-commercial comments have been voiced even in the commercial heartland of design by people like Georg Nelson, who lamented Henry Dreyfuss for his commercialism after the 1950s; cf. Flinchum (1997, pp. 138–139).

4.Darò (2003). For Superstudio, see Lang and Menking (2003).

6.See DAM (2007).

7.Betsky in Blauvelt (2003, p. 51). In another essay, he has characterized Droog as a “collection of detritus of our culture, reassembled, rearranged and repurposed … they have institutionalized political and social criticism of a lifestyle into design and thus into at least some small part of our daily lives” (Betsky, 2006, pp. 14–15). Interestingly, most design researchers do create original designs rather than redo or remake things, even though this has been routine in the art world, especially in the 1990s (Foster, 2007, pp. 73–74).

For design researchers, contemporary art and design provide a rich intellectual resource. It links research to historically important artistic movements like Russian constructivism, surrealism, and pop art. It also links research to Beat literature, architecture, and music. 8 It certainly created links to radical writers and theater directors like Luigi Pirandello, Bertolt Brecht, and Antonin Artaud, who broke the line between the artists and their audience. Through these artistic references, design research also makes connections to some of the most important intellectual movements of the twentieth century.

8.Barbara Radice (1993) discussed at length Ettore Sottsass Jr.’s contacts to Beat poets and novelists in San Francisco, and how he introduced their work to Milan and Milanese designers.

6.1. The Origins of Showroom

The most influential program in Showroom is critical design, which has its origins in the 1990s in the Computer-Related Design program of the Royal College of Art (RCA) in London. Collaborations with Stanford’s Interval Research and European Union pushed this famed art school into research. Key figures were Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, who coined the term “critical design” to describe their work. Above all, critical design was indebted to critical theory, but its debt to Italian radical design and radical architecture groups of the 1960s–1980s is also clear. These groups challenged the modernistic credo of post-war architecture and design with non-commercial conceptual and behavioral designs. 9 Building on this heritage, critical design tried to make people aware of the dangers of commercial design. The aim was to help people discover their true interests rather than accept things in shops as such. 10

9.See Parsons (2009, p. 143). For radical design, see Celant (1972, pp. 382–383); also quoted in Menking (2003, p. 63).

10.Dunne’s quote is in Parsons (2009, p. 145). For another definition, see Dunne and Raby (2001, p. 58).

Early studies in critical design focused on people’s relationships to electromagnetic radiation, building on those few artistic and design projects that had questioned commercial approaches to designing electronic devices. 11 Later, this work turned to exploring the impact of science on society. The main impetus was the debate on genetically modified food (GM), which came to the market from laboratories and agribusiness practically without debate, and raised a public outcry so loud that several European countries imposed limitations on GM products. 12 To avoid this mistrust and polarization of debate, critical designers today work with cutting-edge science, opening up science to debate before mistrust steps in. 13 Recent work has explored biotechnology, robotics, and nanotechnology. By building on science, critical design can look at the distant future rather than technology, which has a far shorter future horizon. 14

11.For example, Weil (1985); Dunne’s (2005) Hertzian Tales is a virtual cornucopia on this work.

12.See Parsons (2009, pp. 146–147).

13.Dunne (2007, p. 8) and Kerridge (2009).

14.See especially Material Beliefs, a project in which Goldsmiths and the Royal College of Art collaborated. The best document is Beaver et al. (2009).

Another track also came from RCA’s Computer-Related Design program. Its main inspirations can be found in avant-garde artistic movements in post-war Europe rather than design. As the key early publication, the Presence Project, related, “we drew inspiration from the tactics used by Dada and the Surrealists, and especially, from those of the Situationists, whose goals seemed close to our own.”15 The situationists tried to create situations that lead people to places and thoughts that they do not visit habitually through dérive (roughly, drift) and détournement (roughly, turnabout). 16 In London, media embedded in ordinary objects like tablecloths provided these passageways. 17 Other artistic sources have been conceptual art, Krzysztof Wodiczko’s “interrogative design,” and relational aesthetics, in which the subject matter is human relations rather than situations. 18

15.Presence Project (2001, p. 23). For situationism, see especially Debord (1955). Situationism shares a curious historical link to the Bauhaus (or more correctly, Ulm), which has been recently analyzed by Jörn Etzold (2009). The Danish artist Asger Jorn was a pivotal figure in early situationism. He was a founding member of the group CoBrA (Copenhagen, Brussels, Amsterdam). When he heard that Max Bill, a former student of Bauhaus, was building a new design school in Ulm in continuation of the Bauhaus, he contacted him, arguing against Bill that the Bauhaus is not a doctrine with a place, teaching, and heritage, but artistic inspiration. Jorn founded a competing organization he called the Imaginary Bauhaus, which soon became the International Movement for an Imaginist Bauhaus (IMIB).After learning about the Lettrists in Paris and establishing contact with Michèle Bernstein and Guy Debord, the two groups joined forces. One of its name proposals was IMIB, but it was discarded for the Situationist International, probably due to Deboard’s negotiation skills. As years went on, Debord became the main figure. For him, the father to be murdered was Sartre rather than Gropius.The connections of the situationists and design in Bauhaus style are distant. For Walter Benjamin, the sparse aesthetic of Bauhaus spaces opened materials for experience in ways in which there was no correct use anymore. The situationists tried to achieve something similar by opening the city with their dérives and dépaysements (disorientations). In this sense, the latter group shares a modernist credo, even though its materials, situation-changing aims and techniques could hardly be more different from the material and specific practice of the Bauhaus. Still, important differences remained:“…whereas Bill’s HfG in Ulm emphasized inheritance [from Bauhaus], doctrine, and continuity, Jorn and Debord’s counter-effort was aimed above all at the intensification and consummation of disinheritance, as well as the affirmation of that absence of experience that Benjamin had identified as the impetus of modernity in the Bauhaus.” (Etzold, 2009, p. 160).

16.Guy Debord’s situationist notion of spectacle, from which he wanted to save people, is indebted to Marx’s notion of commodity fetishism, and in particular, Georg Lukacs’ Hegelian interpretation of Marx, which gave humans an important role in changing history instead of reducing human action to economic relationships alone. Other important sources of situationism were French existentialism, surrealism, and Antonin Artaud’s theater; cf. Jappe (1999). See also Debord (1958).

17.See Debord and Wolman (1956). The situationists urged artists to place artistic work into everyday settings, where it matters to ordinary people. Nicholas Bourriaud (2002, pp. 85–86) noted that what is missing from this notion are other people: constructed situations derail people as individuals, but not direct them to see through those social relationships that define their habits. As such, the situationists were one group in a long list of twentieth century avant-gardists, including Dada and surrealism, but also Allan Kaprow’s happenings, the Fluxus movement, Joseph Beyus’ performance art, and Yves Klein’s hard-to-classify work; cf. Bourriaud (2002, p. 95).

18.The notion of relational aesthetics is from Nicholas Bourriaud (2002), the French critic and curator. Gaver et al. (1999), Hofmeester and Saint Germain (1999, p. 22), Gaver et al. (2004). The reference to Calle and Wearing is from Gaver (2002). The Presence Project (2001, pp. 23, 82–83) also lists artists like photographer John Baldessari and filmmaker Cindy Sherman as sources of inspiration. For discussions on Calle’s (2010) work, see Sophie Calle: The Reader. A good introduction to Wearing’s work is Ferguson et al. (1999).

The turning point was the Presence Project, an EU-funded study that developed media designs for three communities: Bijlmer in Amsterdam, Majorstua in Oslo, and Peccioli in Italy. While its designs were typical media designs of the era, including things like “Slogan Bench” and “Image Bank,” each was installed for brief field trials in Bijlmer. The main legacy of this project was the “cultural probes” that by now have become a routine part of design research in Europe. 19 Later, this line of work produced a constant stream of media-oriented design work, like Drift Table, History Tablecloth, and Home Health Horoscope. 20

19.Cultural probes were introduced for the first time to an international audience in Gaver et al. (1999).

20.For Drift Table, see Boucher and Gaver (2007), History Tablecloth is from Gaver et al. (2006) and Home Health Horoscope is reported in Gaver et al. (2007).

These prototypes became so robust that they could be field tested for months. The aim is to develop technology and find ways to create a “deep conceptual appropriation of the artifact.”21 Still, at the heart of this work is the situationist spirit. The task of design is to create drifts and detours, just like the Web does in making it easy to jump from one subject to the next.

21.Gaver et al. (2003, pp. 233, 235–236).

6.2. Agnostic Science

Showroom had an agnostic attitude toward science in the very beginning. The sharpest formulation of the ethos can be found from the Presence Project, which studied three communities in Europe with cultural probes and then went on to do design for these communities. The project book provides a detailed description of the design process with a great deal of detail about the cultural probes, concept development, and how people in these communities made sense of the design proposals. In one of the project’s key statements, Bill Gaver tells how “each step of the process, from the materials to our presentation, was designed to disrupt expectations about user research and allow new possibilities to emerge.”22

22.Presence Project (2001, pp. 22–23).

The final section of the book draws a line between epistemological and aesthetic accountability. The former tries to produce causal explanations of the world and is epistemologically accountable. For example, “scientific methods must be articulated and precise … [allowing] the chains of inference used to posit facts or theories to be examined and verified by independent researchers.” Facts at the bottom of science also have to be objective and replicable, not dependent on any given person’s perception or beliefs. By implication, these requirements severely constrain what kinds of investigations can be pursued.

Against this, the Presence Project constructs the notion of “aesthetical accountability.” Success in design lies in whether a piece of design works, not in whether it was produced by a reliable and replicable process (as in science). Hence, designers are not accountable for the methods: anything goes. They do not need to articulate the grounds for their design decisions. The ability to articulate ideas through design and evaluate them aesthetically “allows designers to approach topics that seem inaccessible to science — topics such as aesthetic pleasure on the one hand, and cultural implications on the other.”23 Surrealism, Dada, and situationism provided ways to get into dream-like, barely worded aspects of human existence. Field research gives access to the routines and habits, but these art traditions focus on associations, metaphors, and poetic aspects of life.

23.Presence Project (2001, p. 203).

There are many problems with this distinction. “Science” is characterized narrowly, and it sounds more like a textbook version of philosophy than a serious discussion. If one reads any contemporary philosopher or sociologist of science and technology, this description faces difficulties. For this reason alone, it is important to understand its polemic and provocative intent. For the philosophically unaware, it underestimates the power of science and overestimates the power of art and design to change the world. Another troublesome claim is the idea that science cannot access cultural implications. Believing this would delete the possibility of learning from the humanities and the social sciences, which are an important source of knowledge of culture and society. After all, design ethnographers do just that: study culture for design.

6.3. Reworking Research

The agnostic ethos is also reflected in the language used to talk about research. For example, instead of talking about “conclusions,” researchers talk about disruptions and dialog. Also, the Presence Project talked about “returns” rather than data. Cultural probes were specifically developed for inspiration, and they were described as an alternative to the then prevailing methods of user research. These visual methods were inspired by psychogeography and surrealism, and they were described as “projective” in the sense of projective psychology.

Researchers have reworked research practices to reflect these beliefs. The purpose of the Presence Project was not about comprehensive or even systematic analysis. The project was happy to get “glimpses” into the lives of people from probe returns and use these glimpses as beacons for imagination. 24 Instead of analysis, “design proposals” are arrived at through a series of tactics rather than systematic analysis. Bill Gaver explained these tactics in the following manner.

24.Presence Project (2001, p. 24).

Tactics for using returns to inspire designs

1. Find an idiosyncratic detail. Look for seemingly insignificant statements or images.

2. Exaggerate it. Turn interest into obsession, preference to love, and dislike to terror.

3. Design for it. Imagine devices and systems to serve as props for the stories you tell.

4. Find an artefact or location.

– Deny its original meaning. What else might it be?

– Add an aerial. What is it?

– Juxtapose it with another. What if they communicate?25

25.Gaver (2002, slides 78-79).

As probe returns were mailed to London from research sites, they were spread out on a table. Researchers who came by simply discussed pieces people had sent them, trying to be like gossipers: creating a coherent story of what they saw, with some touches of reality, but only some. The instrument was the researcher, who neither analyzed nor explicated data as an outside expert. Instead, he filtered things he saw through his own associations and emotions. 26 As long as we accept the idea that people encounter the world with dreams, fable-like allegories, and moralities, this approach to analysis is justified. If parts of the human world are non-rational, methods should be too. It is difficult to select a word stronger than “gossip” to create distance to science.

26.This tactic is reminiscent of psychoanalysis, where the analyst listens to the feelings that animate the patient’s talk, and uses his own feelings to make sense of the patient’s free associations. For a famously clear exposition of psychoanalytic technique, especially the interplay of “transference” (the patient’s emotions) and “countertransference” (the analyst’s feelings that respond to the patient’s feelings), and how they are used in deciphering the patient’s psyche, see Gaver et al. (2007).

It is also easy to imagine that “field testing” of the prototypes has artistic overtones. Ever since Design Noir, the Presence Project, and Static!, designs have been made public for longer and longer time periods; these are tests only in a nominal sense of the term. The aim of this fieldwork is to provide stories, some of which are highlighted as “beacons” that tell about how people experience the designs and what trains of thought they elicited. These stories are food for debate; they are not meant to become facts (see Figure 6.2). 27

27.For example, Gaver et al. (2007, pp. 538–541). There are precursors to all of this. In the humanities, this approach is called explication du texte or close reading. The difference is in the means: design is a material practice that aims at changing behavior through this material practice. Thus, rather than descriptive, the method is projective, done through design proposals.

This research lives on in books, patents, and doctoral theses, as well as in exhibition catalogs and critical discussions in art journals, galleries, and universities. The outreach can be substantial, like in the case of the Design and the Elastic Mind exhibition in the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). 28 As Dunne stated in Objectified, a documentary by Gary Hustwit, by going into places like MoMA, one can reach

28.Design and the Elastic Mind exhibit, 2008.

hundreds of thousands of people, more than I think if we made a few arty and expensive prototypes. So I think it depends. I think we’re interested maybe in mass communication more than mass production.29

29.Objectified, 1 hour, 09 minutes, and 35 seconds – 1 hour, 10 minutes, and 03 seconds.

Still, one reason for why Showroom has a research following is because critical designers write about their work in ways recognizable to researchers. They tell the whole story from initial ideas to prototypes and how people understand them. The prototypes may be forgotten, but their message lives on in books.

6.4. Beyond Knowledge: Design for Debate

To go beyond individual projects, Showroom relies on debate rather than statistics, like Lab, or precedents and replication, like Field. It questions the way in which people see and experience the material world and elicits change through debate.

This goes back to the critical and artistic roots of these approaches. Design provides a “script” that people are assumed to follow, and they usually do. 30 If people follow these scripts, they become actors of industry and its silent ideologies. Design structures everyday life in ways people barely notice. Usually, these scripts give people simple and impoverished roles, like those of the user and the consumer. 31

30.Akrich (1992) talks about the scripting and descripting that technology imposes on people.

31.As Dunne told to Parsons (2009, pp. 145–146). There are many ways to formulate this impoverishment in literature cited in this chapter. For example, existentialists like Jean-Paul Sartre would talk about bad faith, Nietzsche about slave morality, Marx about false consciousness, and Freud about neuroses. These concepts surface once in a while in design. For example, Quali Cosi Siamo — The Things We Are, an exhibition of Italian design curated by Alessandro Mendini for Triennale di Milano in Summer 2010, was partly based on psychoanalytic metaphors.

To give design more value, designers can adopt a critical attitude to make the public aware of their true interests. Critical designers look to shake up the routines of everyday life. Dunne summarized the primary purpose of critical design:

to make people think…. For us, the interesting thing is to explore an issue, to figure out how to turn it into a project, how to turn the project into some design ideas, how to materialize those design ideas as prototypes, and finally, how to disseminate them through exhibitions or publications.32

32.Parsons (2009, p. 145).

The methods for making people think borrow heavily from art. The designs and the way in which they are explained lean toward Verfremdung, as in “estrangement,” similar to critical theater by the German playwright Bertolt Brecht. For example, by adding inconvenient nooks into a chair, designers create distance from what people normally take for granted. Debate is a precondition to being critical toward the ideologies of design as usual as well as seeing poetry in ordinary things like Zebra crossings (see Figure 6.5). 33 Researchers get engaged with the world, taking a stance against its dominant ideologies. With hypothetical designs, research can explore technological possibilities before they happen. 34 Design works like an inkblot test on which people can project their questions and worries. 35

33.Bergström et al. (2009).

34.Seago and Dunne (1999, pp. 15–16), Dunne in Design Interactions Yearbook (2007, p. 8).

35.Beaver et al. (2009, pp. 110–111). The problem with staying within design and thus trivializing is pointed out by Jimmy Loizeau on p. 111.

6.5. Enriching Communication: Exhibitions

For many researchers in Showroom, exhibiting objects such as prototypes, photographs, and video are as important as writing books and articles. The exhibition format encourages high-quality finishing of designs over theory and explanation. At times, exhibitions may take the role of a publication. As Tobie Kerridge noted following Bruno Latour, exhibitions at best are Gedankenausstellungen, thought experiments that offer curators more freedom than academic writing. 36

36.Kerridge (2009, pp. 220–221). Design has been exhibited for decades. The past decade saw two developments: design was turned into art, which drove the prices of prototypes and one-offs sky high. As expected, there are already exhibitions mocking such ideology by celebrating ordinary industrial things, while simultaneously treating them as ready-mades (see Design Real, Grcic, 2010).

In research exhibitions, designs are exhibited in the middle of theoretical frameworks rather than as stand-alone artworks. Also, design researchers typically want to create distance from the art gallery format. They connect their work to the commercial roots of design with references to furniture shops and car shows. Tony Dunne wrote:

The space in which the artifacts are shown becomes a “showroom” rather than a gallery, encouraging a form of conceptual consumerism via critical “advertisements” and “products”…. New ideas are tried out in the imagination of visitors, who are encouraged to draw on their already well-developed skills as window-shopper and high-street showroom-frequenter. The designer becomes an applied conceptual artist, socializing art practice by mobbing it into a larger and more accessible context while retaining its potential to provoke people to reflect on the way electronic products shape their experiences of everyday life.37

37.Dunne (2005) and Dunne (2005, p. 100).

Exhibiting in places like shops and showrooms also connects critical work to everyday life. In projects like Placebo and Evidence Dolls, Dunne and Raby gave their products to ordinary people38 As encounters with everyday life become more important, this approach gets closer to field research. 39 The idea, however, is to use people’s stories to create a rich understanding of the prototypes, not to gather detailed data for scientific research. Field studies and writing become a part of the Showroom format, but the aims are conceptual.

38.Dunne and Raby (2001, p. 75).

39.See Dunne and Raby (2001); Routarinne and Redström (2007), Sengers and Gaver (2006), Gaver et al. (2007).

6.6. Curators and Researchers

There are also problems when research takes place in the exhibition context. Often, exhibitions are not solo shows but compilations of many projects collected under an umbrella envisioned by a curator. 40

40.MoMA’s exhibition Design and the Elastic Mind is a good example of the power of the curators. Critical design was only part of the exhibition, which also showed works from artists and scientists specializing in visualization and digital art.There are curators and critics who know the difference between art and design and take designers’ reluctance to be labeled as artists seriously. The best recent example comes from Berlin’s Helmrinderknecht gallery focusing on contemporary design. Sophie Lovell curated an exhibition called Freak Show: Strategies for (Dis)engagement in Design that ran in this gallery from November 13, 2010, and January 15, 2011. Exhibited was work from ten groups of designers, two of them coming from critical design. Each group challenged the prevailing ideas of design as usual, and explored ways in which design could become a life-serving force. These ways consisted of using bioengineering in James Auger and Jimmy Loizeau’s work coming from Material Beliefs, and El Ultimo Grito’s animalistic tables made of cardboard and artistic resin. The exhibition was a mélange of concepts, one-offs, small series products, and to-be production pieces.

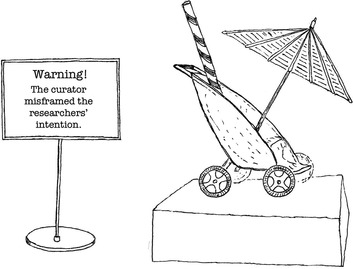

Typically, the curator places the work into a new framework by juxtaposing things that were not necessarily included in the original research projects. Some research concerns and knowledge might be present in the exhibition, but many are not, and yet others are typically rephrased or substituted. Further, most designs are ambiguous and often designed to prompt imaginative interpretation and interrogation. 41 This explanatory framework reflects the curator’s interpretation of the research, which may differ significantly from the original goals of the researchers (Figure 6.3).

41.See in particular Gaver et al. (2003, 2004).

For example, the Energy Curtain from the Swedish Static! project has been used and showcased in diverse settings. Energy Curtain has been studied in several Finnish homes, it has been at energy fairs to represent a national research program, and it has been in the touring exhibition Visual Voltage commissioned by the Swedish Institute. The exhibition has been in places as diverse as the Swedish Embassy in Washington, design exhibitions, expos and museums, and a luxurious shopping mall in Shanghai. It would be naive to think that the original research intent shapes how people look at design and read meaning into it in all of these places. When researchers’ prototypes travel the world without the original theoretical context, they may even be treated like products. Approval is expressed through the question: Where can we buy this?42

42.Indeed, there is a market for prototypes by star designers like Philippe Starck and Ron Arad, whose prototypes may be valued at hundreds of thousands of dollars. This market is significant enough to have its own chronicler (see Lovell, 2009). To our knowledge, there is no market for design researchers’ prototypes, but after institutions like MoMA have exhibited design research, the day will come when we will see research prototypes in auction houses.

Although exhibitions create many possibilities for communicating design research, they also create a need to carefully consider how other events, writings, and publications can be used to complement them to keep researchers’ intentions alive. It is important to engage locally in staging further discussions and debate. For researchers, the attempt to control these meaning-making processes around design means extra work and traveling, which also makes research expensive. 43

43.For example, when Visual Voltage went to Berlin, the exhibition was expanded with local designers. There were events and a design research workshop around the themes of the project. See www.visualvoltage.se/.

6.7. How Not to Be an Artist

When techniques and practices are borrowed from art, research may be labeled as art and treated accordingly — as political or social statements rather than serious design research. There are plenty of developments that push design to art. For example, curators find it easy to integrate conceptual design into art exhibitions, as in Hasselt, Belgium, where the art museum Z33 organized the 2010 exhibition Design as Performance as a sequel to its Designing Critical Design exhibition in 2008. Despite its name, the 2010 exhibition was framed explicitly as art, and most of the participants were artists. 44

44.For Design as Performance, see Z33 (2010); for one-offs and prototypes as art objects, see Lovell (2009); and for art exhibitions showing that industrial products are not art (sic), see Grcic’s (2010) Design Real.

It is critical that designers fight being labeled as artists. Anthony Dunne explained how he draws the line:

What we do is definitely not art. It might borrow heavily from art in terms of methods and approaches but that’s it. Art is expected to be shocking and extreme. Design needs to be closer to the everyday life, that’s where its power to disturb comes from. Too weird and it will be dismissed as art…. If it is regarded as art it is easier to deal with, but if it remains as design … it suggests that the everyday as we know it could be different, that things could change.45

45.Anthony Dunne in Design Interactions Yearbook (2007, p. 10).

One way to distance design from art is to take discourse out into the real world. Much of the early work focused on changing design, but recently designers are getting engaged in larger societal issues. 46 We have already described how critical design has shifted its attention upstream from criticizing design to making science debatable. 47 The Stockholm-based project Design Act is another example. It discusses “contemporary design practices that engage with political and societal issues” by examining “tendencies towards design as a critical practice,” which is ideologically and practically engaged in these issues. 48 If designers participate in dialog about the meaning of their work, it is not only curators, critics, and media who define it. A degree of control can be gained this way.

46.Redström (2009), pp. 10–11.

47.See Design and the Elastic Mind, Design Interactions Yearbooks after 2007, what Timothy Parsons (2009) says about design for debate, and Ericson et al. (2009).

48.See www.design-act.se/.

The main challenge of this tactic is to take debate to places where it matters. If researchers stay within the art world, it only strengthens the art label. To make debate meaningful, it ought to be organized in companies, government offices, malls, and community meetings, and face the questions contemporary artists face when they have turned human relationships into art. As the British critic Claire Bishop noted, the question for art is whether it ought to be judged by its political intentions or also by its aesthetic merits. 49 Is serious social content enough to justify a piece of design research, or should it also be judged on its aesthetic merits? Mere disturbance is easy, but is it enough (Figure 6.4)?50

49.Bishop (2007, pp. 64–67) raised this question, suggesting that its history can be traced back to “Dada-Season” in Paris in 1921. She also suggested that relational art should somehow try to create “highly authored situations that fuse social reality with carefully calculated artifice” (p. 67). Art and by implication, design, can and perhaps even should disturb viewers, and learn from earlier avant-gardes like Dada, surrealism, or in America, Beat poetry. To promote change, one should not accuse art of mastery and egocentrism if it seeks to disturb rather than only something that emerges through consensual collaboration.The difficulty lies in negotiating the line between constructing a disturbance that evokes new thought models and shocking. As Grant Kester (2004, p. 12) noted in his study of dialog in art, much of the twentieth century avant-garde built on the idea that art should not so much try to communicate with the viewers, but rather seek to challenge their faith to initiate thinking. The premise was that the shared discursive systems (linguistic, visual, etc.) on which we rely for our knowledge of the world are dangerously abstract and violently objectifying. Art's role is to shock us out of this perceptual complacency, to force us to see the world anew. This shock has borne many names over the years: the sublime, alienation, effect, l'amour fou, and so on. In each case, the result is a kind of epiphany that lifts viewers outside the familiar boundaries of common language, existing modes of representation, and even their own sense of self. As Kester noted, recently many artists have become considerably sophisticated in defining how they work with the audience. Rather than shocking, they aim to create work that encourages people to question fixed identities and stereotypes through dialog rather than trauma. Prevailing aesthetics in such work is durational rather than immediate.Of course, this is the stance held by critical designers, as well as other representatives of Showroom, even though they have not been less vocal about their design tactics. The aim is to lead people to see that there are ways of thinking and being beyond what exists in the marketplace, but the way to lead people away from their habits is gentler and far less ambitious than in earlier avant-gardes that came from rougher times.Another problem with shocking is that contemporary art has gone to such extremes that it is increasingly difficult to shock. Shocking also leads to the problem of trivialization — something is shocking so it must be art and hence inconsequential. For good reason, critical designers try to avoid this tactic in their work as well as their discourse. A good discussion of the problems of shocking is den Hartog Jager (2003).

50.With the exception of critical designers, there are few debates in which designers study these questions. Andy Crabtree’s (2003) advice is to think of technology as breaching experiments (see also Chapter 8), and Bell et al.’s (2005) argument is that designers need to make things strange to see things that are grounded in various “ethnomovements” of the 1960s, not contemporary art.These movements argued for studying people from within, through their meanings, rather than using researchers’ categories. One way to make the routine noticeable, unquestioned, and moral is to disturb and breach those routines. The reader can try this at the workplace by doing one of Harold Garfinkel’s (1967) breaching experiments. Take any word people routinely use and press them to define it. Calculate how many turns it takes before people get angry at their friends, who should know what words like “day” or “flat tire” mean.In critical design, as in contemporary art, disturbance is usually an opening into critical reflection rather than into studying the routine activities of everyday life. The difference may sound subtle, but it is essential.

Another tactic is to do design at a high professional level. This catches the attention of professional designers, who do not get to label researchers’ designs as art, bad design, or simply not design. If researchers succeed in being taken seriously as designers, they may be able to direct attention to the intention behind the work.

The most eloquent articulation of this tactic comes again from Dunne and Raby. They stress that their conceptual products could be turned into products because they result from a design process, are precisely made, require advanced design skills, and project a professional aura. Fiona Raby, in an interview to the Z33 gallery in Belgium, said:

By emphasizing that this is design, we make our point more strongly. Though the shock effect of art may be greater, it is also more abstract and it doesn’t move me that much. The concept of design, however, implies that things can be used and that we ask questions — questions about the here and now. What is more: all our works could actually be manufacturable. No one will of course, but as a matter of principle, it would be possible.51

51.Raby (2008, p. 65).

Here critical designers meet post-critical architects and many contemporary artists. The aim is to create ideologically committed but good, honest, and serious design work to make sure that attention focuses on design rather than labeling. 52 This is how many design revolutions have come about; for example, Memphis designs were mostly theoretical, but no one could blame them for bad design. They were taken seriously and, ultimately, conquered the world.

52.For post-critical architecture, see Mazé (2007, p. 215); for contemporary art, see Bourriaud (2002, pp. 45–46).

A third tactic is to study prototypes in real life. An early example of following what happens to design prototypes in society is Dunne and Raby’s Design Noir, and another is the Finnish domestication study of two prototypes done by the Interactive Institute, Energy Curtain and Erratic Radio. 53 In London, Bill Gaver’s group at Goldsmiths is also working on longer and more complex studies that move beyond notions of evaluation. 54

53.Routarinne and Redström (2007).

Empirical research turns even very explorative designs into research objects. However, for Showroom researchers, fieldwork is typically not about issues around use but about issues like form. For instance, they may ask how static and visual notions of form are moving toward the performative and relational definitions. They also gather material that helps them to build better stories and concepts for their exhibitions.

6.8. Toward Post-Critical Design

Recent work at the Interactive Institute in Sweden shows how researchers can deal with these problems. This work has built on design, philosophical investigation, and more recently, critical discourse in architecture. 55 This work has explored computational technology from an aesthetic perspective and combined traditional materials with new technologies. 56 Its topic is how sustainable design may challenge thinking about energy and technology. Static! explored ways of making people aware of energy consumption through design. Switch! explored energy use in public life and architecture. 57

55.Mazé and Redström (2007), Mazé (2007).

56.See projects Slow Technology and IT+Textiles.

57.Mazé and Redström (2008, pp. 55–56).

Static! and Switch! consisted of several projects. Design examples were reinterpretations of familiar things. Throughout, the idea was to build new behaviors and interactions into old, familiar forms like radios and curtains. 58 The purpose was to create tension between familiar forms and unexpected behaviors to elicit new perceptions, discussion, and debate.

58.See Ernevi et al. (2005).

For example, one of the subprojects in Static! was Erratic Appliances — kitchen appliances that responded to increasing energy consumption by malfunctioning and breaking down. One prototype was Erratic Radio. 59 It listened to normal radio frequencies and frequencies emitted by active electronic appliances around the 50Hz band. When the radio sensed increasing energy consumption in its environment, it started to tune out unpredictably. To continue listening, the user had to turn some things off. Erratic Radio has an iconic Modernist shape with a hint of classic Braun design, which gave it a persuasive and usable quality and underlined that the difference with normal radio was behavioral. Its inspiration was John Cage’s Radio Music, but it took an opposite approach to Daniel Weil’s Bag Radio, which broke the form of the radio but not its function. Prototypes like Erratic Radio were done in the spirit of the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s thought experiments: they were aimed at questioning things we take as necessities even though they result from industrial processes.

59.First reported in Ernevi et al. (2005).

Symbiots from the Switch! project at the Interactive Institute showed some artistic tactics at work. Inspired by notions such as symbiosis and parasitism in biology, Symbiots explored how these natural processes could be used to change ordinary forms into new ones. In Symbiots, graphical patterns, architectural configurations, and electrical infrastructure were turned into a photo series in the genre of hyper-real art photography. The intervention started with neighborhood studies. Residents participated in making the photographs, distributing posters, and discussions. The photo series were done in two different formats, art photographs and posters, to emphasize that there is more than one way to construct design objects.

This kind of work faces several problems. Most of this work is reported in scientific conferences and exhibited in contemporary design galleries. While it also may have some presence at expos and fairs and other venues closer to a commercial context, it is still clearly placed outside the market. If researchers want to show how design can make the world a better place, they have to go where people are. This does not happen through intellectual debates in galleries.

The pros of this step over the boundaries of the design world are obvious, but so are the cons. While fellow designers and critics may be able to pick up the intention behind the work and respect it, this cannot be taken for granted in a place like a shopping mall. Shopping malls place the work in a commercial frame in the original spirit of the Showroom metaphor, while an embassy places it into a political and national frame. This is unavoidable: design does not exist in a void. However, the key question is how to make sure that the research intention is not hijacked to serve someone else’s interests (see Figure 6.5).

There are no easy answers to this question. Engagement and commitment have come to stay in constructive design research, but it is far more difficult today than it was in the 1960s and requires elaborate tactics. It is hardly possible to be counted as an avant-garde artist by emptying a glass of water into the North Sea, as Wim T. Schippers did in the 1960s, and shocking the audience has gone to such extremes that it has become very hard to continue like this. 60 Design has had its own share of failures, such as claims to solve the refugee crisis by building better tents. In this case, anything does not go. 61 It pays to be careful with this type of claim or risk being dismissed as art. 62 Like artists and architects, designers today tend to make local rather than global commitments and exhibit doubts and controversies in their work. Showroom is about exposing, debating, and reinterpreting problems and issues. Ambiguity and controversy belong to it, just as they belong to contemporary art. 63

60.For Wim T. Schippers, see Boomkens (2003, p. 20).

61.For this example, and for discussion on designers using artistic tactics for photo ops, see Staal (2003, p. 144).

62.Dunne (2007, p. 10).

63.For a note on these doubts and commentaries on architect Rem Koolhaas’ work, see Heynen (2003, p. 43).

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.