Chapter 13. Presenting Your Portfolio

Planning, design, and production are the major stages in digital portfolio development, and they are certainly the ones that take the most energy and time. But uploading files or burning a disc doesn’t mean your work is done. In creative endeavors, exquisite presentation is not a bonus—it’s the required last step in designing and producing a portfolio. It matters tremendously how you present your portfolio to others, both when you are physically present and when the portfolio must speak for you.

This final chapter considers the presentation as part of your portfolio design. When your artwork, your product, and your presentation are in harmony, you make a powerful statement to a prospective client or employer: “This person loves and cares about their work.” That’s exactly the type of person anyone would want to have on their team.

Testing your work

When you discover a bug while you’re using a program, you get irritated and angry. Well, digital portfolios are software, too. It is much better to find a problem before it reflects badly on you and your work.

You may not think you need to test your work if your portfolio isn’t interactive, but sometimes even in the simplest projects you can let something silly slip through. If you’ve made PDFs, or created a simple slideshow, or even used a template on a sourcebook site, you should still spend the time to verify that everything works, looks good, and reads well.

How to test

If you don’t have one already, make a spreadsheet list of each page. Compared with most commercial websites, your portfolio is a small project and it’s absolutely possible to test everything. As you test each page, check it off on the list. If you find a problem, either fix it immediately or carefully write down what’s wrong on the spreadsheet. Don’t depend on your memory!

A successful procedure is thorough and complete, and includes the following:

• Test against your site map. If you made a website or integrated disc presentation, you should have a good site map to refer to. (See Chapter 10, “Designing a Portfolio Interface.”) Are the pages linked from the places you planned, and are the links from those pages correct?

• Test on different computers. Open your project on a different computer. You may have browser default settings on your working machine that you take for granted, or you may discover errors in a style sheet or a font. You may also notice, on a more- or less-powerful computer, that some animations move too slowly or are much faster than you thought that they would be.

• Test on different platforms. If you designed your work on a Mac, test it on a Windows computer, and vice versa. Fonts, colors, and browser elements may look different or not work properly.

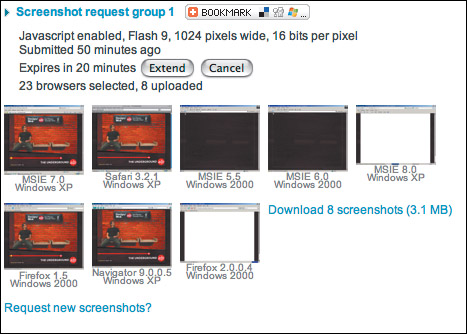

• Test on different browsers. Not only are there visible differences on different platforms, there are a surprising number of formatting differences on the same platform with different browsers. You must at least test on Firefox and Safari on a Mac, and on Firefox and Microsoft Internet Explorer on a PC. Even better, once you have a URL in place, visit Browsershots (browsershots.org). Not everyone makes a point of updating their operating systems and browsers when new ones are released, and a quick check will let you know if a major browser has problems displaying your work as you’ve designed it. If your test page doesn’t pass muster, you know exactly which browsers you’ll need to test it against after you’ve researched the problem.

BROWSERSHOTS.ORG

Browsershots submits your URL to the collection of servers you specify. As they load, they appear as thumbnails that link to the full screenshot. Not all failed loads are serious—your portfolio is not an e-commerce site. As long as all of the browsers that are likely to be on your target audience’s computers load correctly, your page passes the test.

• Test at random places. Unless your work is in one Flash SWF, people could gain access to your site through a chance link or Google search, not from your site’s homepage. If you open your site randomly, does all your navigation still work?

• Test with other people. Watch someone else look through your portfolio, preferably not someone who’s been working on the computer next to you while you developed it. Do they click in places that you never intended? If they do, does anything unexpected happen? If your guinea pig seems confused by your interface or slow to understand your environment, rework the difficult sections.

• Test your media. Particularly if you have created a DVD player interface, you must verify that your disc will work, not just in your own computer or player, but in many player and platform combinations. Use brand-name DVDs: Generic brands are often incompatible. A visit to an electronics megastore can provide an opportunity to pop your disc into a range of players.

What to test

Test everything, really—every page, every image, every interactive state. In particular, watch for the following:

• Fonts. A bug may cause some fonts to be replaced with one that is incorrect or has an incorrect weight.

• Links. When you update, links can break, especially if you retype file names. If you have links to launch an email program, or links that open new windows, make sure they all work. Use absolute links—ones that contain the entire URL (such as http://www.outsidelink.com/folder/mywork.html)—for all external links.

• Images. Images should all be in one image folder, and accessed through a relative link (such as “images/mypix.jpg”), so they won’t generate broken links when you upload your files to a server.

• Downloads. When you download a video clip, does it play on both Macs and Windows? How long does it take to start? Does it play correctly?

• Coding. Different versions of browsers, and browsers on different platforms, can read your code in a variety of ways. Layers, for example, don’t always work on older browsers. You may need to change your code so it works in more browser versions.

• Speed. How long does it take your homepage or Flash preloader to finish? How long does it take each of your artwork images to show up? Are these acceptable times for your target audience?

Getting feedback

Once you’re confident that your portfolio is in good shape technically, get some feedback. The more interviews and reviews you can get, the better. Even an accomplished professional can miss things that a fresh eye will notice. Trusted, discriminating friends are a valuable source. But sometimes, especially when you have created something in a new format, objectivity is very valuable.

It’s easiest to get feedback if you’re a student. In fact, enrolling in a professional development or certificate program at an art school or university can give an older professional access to some of the school’s faculty and placement services—and their portfolio reviews. Don’t be shy about asking a favorite professor for an appointment to discuss your portfolio. How well you do reflects on them, and on the school.

Local professional organizations also sponsor portfolio reviews, often in the spring. They offer the opportunity to get feedback from faculty and professionals from different schools or companies—offering a new perspective on your work.

No matter what your position, look for opportunities for informational interviews. Many design studios, for example, offer a specific process on their website for portfolio feedback. Another great place for feedback is a placement agency. You’ll get unvarnished reactions from a place that sees hundreds of portfolios in your area.

Of course, the online community offers endless feedback. Too endless—there are lots of critique sites. Unfortunately, I can’t recommend one in specific that consistently gives good creative advice, although you are likely to get a better quality of response by posting on a professional portfolio site like Behance or Coroflot than on most technical forum sites (they’re best for software tips and feedback on site function). To figure out if a site will be useful to you, look for three warning signs:

• The site’s design. Even blogs and forums can be designed with taste or without. If they’re using an off-the-shelf look and feel, the feedback they provide may be just as generic.

• Anonymous posters. Do you really want a critique from someone whose handle is “stinkyfoot”?

• Rated reviewers. Except on purely technical advice sites, high-rated reviewers get there by being supportive, not by being effectively critical.

You might have better luck joining—or starting—a local community of creatives who critique each other’s work. Again, professional organizations can be good sources for such a network.

One last consideration about critiquing: You may not always like what you hear. Any professional who is offering feedback should be polite and offer constructive criticism—you shouldn’t have to take tantrums and abuse. But they are doing you a favor if they honestly point out that a project doesn’t belong in your book, tell you that your portfolio needs work, or give suggestions on improving your presentation. Even if you disagree, don’t argue. If you really think that they are wrong, ask someone else. Second opinions can be as useful for portfolios as they are for medical decisions.

WWW.BU.EDU/PRC/PORTFOLIO.HTM

Boston University’s Photographic Resource Center offers free monthly portfolio reviews to its members. It also provides a fee-for-service portfolio review for the entire photographic community.

Packaging a portable portfolio

If you’ve designed and produced a disc portfolio, you’ll probably be sending it out for review. Almost any place you target probably gets scores of other portfolios in a month. You want your work to stand out from that crowd. Generic-looking material could easily be tossed in the trash in a fit of end-of-project house cleaning.

Designing a disc package

There is a difference between adequate and excellent portfolio packaging. Design creativity is of course critical, but good process will help you maintain quality and produce a better package. Consider these issues as you develop your design:

• Maintain design consistency. Connect your physical materials visually to your online portfolio. You might be surprised by how many people begin their package design from scratch. Packaging, like your portfolio, is part of a self-branding process. You should reinforce that branding whenever you can.

• Aim for legibility. You want your package to be distinctive, but your design should never sacrifice legibility for effect. Make sure your name, and the word portfolio figure prominently in your packaging and related materials.

• Design all elements. If you are using a jewel case for your CD, make sure to design all surfaces: front, back, and the side. The side is particularly important, since discs are often stored standing up.

• Design a leave-behind. In addition to having a digital portfolio, it’s always a nice touch to have another form of portfolio leave-behind to accompany it. It offers a way to show your work in tangible form, and can double as a great way to advertise your site. (See “Mailings,” later in the chapter.)

• Print on stiff stock. Your jewel case cover and insert should be printed on (or constructed with) heavy paper. If you’re lucky, it will be opened and closed multiple times as people pass your disc around. You don’t want the design to look shopworn after a few people have handled it.

• Design your print portfolio. You may still be maintaining a print portfolio for pieces that can’t be shown, or don’t work well, digitally. It should be organized and designed to match your digital presentation. The absolute best book on developing a stellar print portfolio is Sara Eisenman’s Building Design Portfolios: Innovative Concepts for Presenting Your Work (Rockport Publishers, 2008).

To raise the odds that your work will be viewed and retained, your digital portfolio should be attractively packaged. At the least, you should design a disc label. Even better is to add a matching sleeve or case and a mailer insert.

Getting the word out

Promotion is not a dirty word. True, there are people whose tireless and egotistical self-flogging give the practice a bad name. But if you believe in your work, you should be prepared to be your own advocate. It’s easy to get discouraged if you don’t have an immediate response once you’ve posted your portfolio, but if you feel your work has value, you must be persistent.

Advertising your site

Publicizing your portfolio is the other side of researching your audience. Take advantage of all the connections you made in lists, forums, and other groups to help your portfolio rise above the noise. In particular, be sure to contact everyone who critiqued your portfolio and send them a personal thank-you with the URL of the final site. If someone was particularly helpful, you might even add a line of thanks or credit in your online portfolio. It may prompt them to send people to see your site, but even if it doesn’t, they’ll appreciate the public thanks.

Add your URL to your email signature, along with a line about your site’s content. Be descriptive, short, and subtle. If you’re good with words, try to include a teaser that will draw people in.

Redo your business card and put your URL on it. Never leave the house without carrying a few business cards with you. Go to art and design events, and offer your card when you can. Both the creative and business worlds run on networking. Contacts in the community can lead to recommendations and referrals later.

Linking and Web 2.0 sites

A finished portfolio is a cause for rejoicing, and considerably more interesting to look at than the results of some Facebook contest. Make sure all your online friends know the address. Add it to your LinkedIn updates. Post work samples with the portfolio URL on appropriate self-publishing sites. Twitter. This is not the time to quiet and modest. Generally, you will get the most mileage out of your new digital portfolio within the first month of its existence, and it would be a shame to waste its shiny, fresh status. If people like your site, they will link to it, extending your network and visibility, and ensuring a small but steady march through its pages for weeks to months. Some of these visits will just be well-wishers. Others will be people asking you for help. But if your work is good, this barrage of connections will also lead potential employers and clients to you. Some of the featured portfolios in this book were found in precisely this way.

Luke Williams has explicitly designed an elegant mailer to use as a leave-behind and as a prequel. Its style evokes the personal writing style he uses to speak directly to his website visitors.

Online contests

To keep traffic coming to their own addresses, many professional portfolio sites, blogs, and even software giants like Adobe sponsor contests for creative work online. Some of these result in actual prizes, like software, web hosting, free upgraded subscriptions, printing, and, yes, money. But all of these goodies are beside the point. What they really offer is priceless: an immediate ticket to professional viability. If you are both talented and lucky, they may help to catapult you into your future career.

Obviously, like winning the lottery, you really can’t base your life on taking first place in a contest. But even gaining a mention will drive traffic to your portfolio and result in invitations to join useful public and private networks. Particularly if you already have work in the wings that might fit the contest’s rules or have time to make the extra effort, you lose nothing from entering the arena. Should you actually gain notice, you have the kind of news that gives you an excuse for mailing and posting.

Contacting individuals

You spent a lot of time researching target audience possibilities. Now is the time to pull that material out. You know who you’d like to work with and for, and now that you have a portfolio, it’s time to let them know about you.

If you found the name of a specific person, email is probably the best way to contact them. Even if their email address isn’t on their website (although it probably is), it’s usually pretty easy to figure it out. Look at the email addresses for other site contacts. Chances are they’re all in one of these formats:

Try them all, one at a time. The incorrect ones will bounce back to you, and the contact person will never know that you tried them. The correct version will hit their inbox.

Be sure to have a subject in the email that describes what you want. Good possibilities are “informational interview request” or “interested in your studio.” Don’t use subjects like “Hi!” or “want a job.” Besides being unclear, they are headings that spam software reads as junk mail. The body of your email should also be clear and direct. Look at Chapter 8, “Creating Written Content,” for suggestions on how to compose an appropriate email cover letter.

If the contact person doesn’t reply, don’t give up. Wait a few days, then politely acknowledge that they might be very busy, and ask if there is someone else at the firm to whom you might direct your email. You want to strike a balance between showing your interest and being too persistent.

Including your résumé

When you send email, of course you’ll include your résumé with your samples. You’ll also include it on a CD or DVD. But these portfolio forms are most useful when you have a personal contact or know of a specific hiring opportunity. With an online digital portfolio, you can choose either to include your résumé or replace it with short descriptive text and contact information.

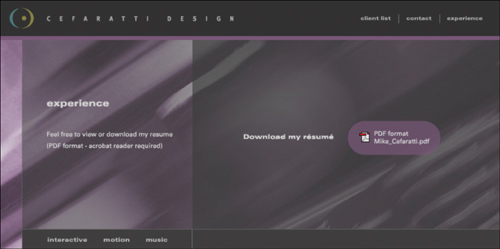

Some people deal with the résumé question by creating a download link to their PDFs. This approach has many benefits. It ensures that your name will find its way into a paper file and encourages viewers to find out more about you while your portfolio is still fresh in their minds.

In some situations, it’s better to use the bio plus contact approach. Separating your résumé from your portfolio can be useful for these reasons:

• Confidentiality. When you put your résumé on a static web page, its text will be searchable. This might seem to be a plus, but remember that few people will search on your name. Instead, your site will come up most frequently when they look for information on your prior—or current—employer. If you are actively looking for a new job while you’re still employed or have had issues with a former employer that might come up in an interview, this information might be better left less accessible.

WWW.CEFARATTI.COM

Mike Cefaratti makes his living as a freelancer. Although he doesn’t include a bio on his site, his résumé is readily available for viewing or downloading to encourage potential clients to examine his impressive experience.

• Contact. Handing out your résumé without requiring any contact takes a possible point of control away from you. After all, your résumé is only important to a company if they are already intrigued by your work. If they email to request the résumé, you have instantaneous feedback on your site. You also have an opportunity to present yourself in a less formal, more personal way—and gain a contact name for future mailings.

• Confidence. A résumé online can imply less skill and accomplishment than you have. A recent college graduate in photography or illustration may already have a solid collection of work from commissions, co-ops, and internships or personal projects. Drawing attention to your youth may imply inexperience to a potential client, when your work says “professional.”

• Customizing. Waiting to send your résumé on request also allows you to customize it slightly to each query. You can create alternate résumés for different situations, sending the most appropriate one when asked. Or you can use it as an opportunity to gain points. After you know who wants your résumé, you can visit their site to find out more about them. If you’ve done a project that’s directly relevant to their clientele but isn’t in your digital portfolio, a PDF along with the résumé can show not only what a good fit you’d be, but that you think fast.

Cold-calling

If you don’t have the name of a person to speak with, call the company. Be straightforward about what you want, don’t make them guess why you’re calling, and, above all, be polite. Ask if you can send your résumé and a PDF, or your portfolio URL. Describe succinctly and clearly the kind of work you do and why you think you might be a good fit with their firm.

Even if your contact says that there are no positions available, or that they’re happy with their current suppliers, send a short follow-up note thanking them for giving you their time, and enclose your résumé and URL. Situations can change quickly, and your information could arrive just as an employee unexpectedly leaves.

Mailings

If you are trying to get as much coverage as possible, one of the best ways to do that is through old-fashioned snail mail. Do not send a copy of your portfolio...send a printed example of your work. One way to do that is with postcards.

Your postcard should be extremely simple: an example of your work on one side, and your name, contact info, URL, and what you do (illustrator, interface designer, photographer, and so on) on the other. Check out www.modernpostcard.com for good-quality, reasonably priced custom postcards.

They’re inexpensive to send, and you can produce them yourself.

Each time you update your site with new work, mail postcards again. If you finish an exciting new project, particularly if you are a creative who lives on freelance work, invite people to visit. That way, your prospects know that you are still around and available. Every fresh and new interaction resets the clock and wipes the dust away from the memory of you and your work. Many studios keep a file of prospective freelancers and collaborators. When a new project comes in that requires a new hire or outside help, that file is one of the first places they look.

The personal presentation

With any luck, between advertising, job listings, and your network, you’ll get the chance to present your work—and yourself. You want to bolster that positive impression you’ve given by doing the same in person.

Rehearsal

After you set up a date for a personal presentation, go through your portfolio and prepare what you are going to say about each piece, and about your work in general. Rehearsal doesn’t mean memorization, which leaves no room for personality or spontaneity. Nor does it mean developing a sales pitch. That turns other creative people off. It does mean having a plan and feeling prepared, which should make you feel more confident.

What to prepare

Good presentations, like good portfolios, have a story behind them. You need to grab your audience’s interest immediately, support that positive first impression, and end on a strong note. Because an online presentation isn’t linear, your emphasis until now has probably been on the overall experience of your portfolio site. But in a personal presentation, the sequence in which you introduce your ideas and present your work is critical.

You’ve already limited your portfolio to your best work. For your presentation, look for the best of the best, and lead off with it. Pull out the extras, the supporting elements of a project, and any work that you couldn’t put online because of contractual issues. You don’t want your presentation to be exactly the same as your site if your site is how you got the interview in the first place.

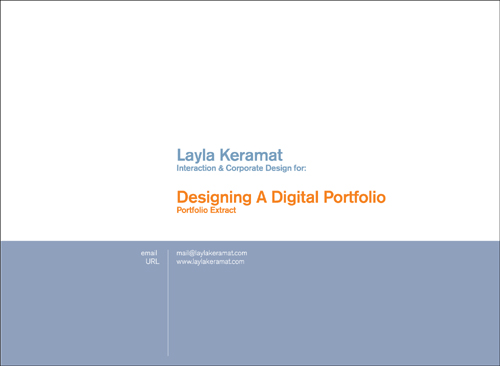

Layla Keramat makes a point of customizing every presentation she makes with the name of the company or client. She continues this customization by reviewing her presentation and shifting the balance of her work toward material that will be relevant to the audience.

How to rehearse

Don’t just rehearse in your head—speak out loud and act the process out. If you are bringing a traditional portfolio with you, go through the physical act of presentation to make sure that it’s easy to pull out mounted boards from a case, and that you can access each individual element without rummaging around for it.

If you’ll be presenting with a laptop, consider customizing the presentation for your audience. Nothing does a better job of telling a group of skeptical listeners how serious you are about their job than an opening screen with their firm’s name on it. If you’ve done a great job in organizing your portfolio, you should already have categorized all your work. Cull through it before the presentation to emphasize the type of projects their firm specializes in.

Ask in advance if you’ll be projecting your work. Most projectors are a generation behind desktops in screen resolution. Make a special version of your presentation to run at 800×600 resolution so you’ll still be able to access your interface if the projector is an older one.

Be prepared

You can’t know in advance exactly who will be present at your interview, or how much knowledge they may have. Even if it’s “just” a screening meeting at a placement agency, bring your portfolio materials.

You’ll want to clarify your role in creating the work, especially if you played more than one role. Did you design, but also create the illustrations or write the copy? Did you do the programming for the prototype? Was the work completed in a very tight time frame? Remember the issues of attribution and honesty in Chapter 12, “Copyright and Portfolio,” and claim only your fair share of the work you present.

Know why you made your creative decisions, and find words to describe them. “It just came to me,” will sound as weak as it is. How can you be hired as a client problem-solver if you can’t describe the problem? If appropriate, bring process materials that aren’t part of your regular portfolio to help you describe how you think.

Talking about your work can also involve listening. I once attended a presentation by a midcareer design professional who turned every query about how he approached a specific client problem into a lecture about how good he was at addressing client problems. Despite his reputation, this introduced doubts in his audience about whether they could work with him. He projected his agenda too clearly.

Think about the personal assessment that you completed in Chapter 1, “Assessment and Adaptation,” and allow yourself to be who you really are. Your chemistry with the interviewers is something you can’t control—either it’s there or it isn’t. But if you’re prepared to field questions about how you deal with deadlines and your experiences in collaborative situations, it will be easier for you to loosen up and let your personality come through.

Dress code

Even if you have very strong opinions about style and dress, avoid extreme clothing, and cover your tattoos. Even if your daily wardrobe is a T-shirt and torn jeans, have one outfit that is clean, ironed, and ready for the public. Being unwilling to adapt your style implies that you are either clueless or inflexible, as well as being someone who would have to be insulated from many clients. Your work had better be astoundingly good to balance these negatives.

Dressing appropriately doesn’t mean that you should show up clad in a corporate uniform. Clients expect a creative person to “look” creative. Sharp, good-quality clothes that telegraph a personal style are very acceptable for professionals in the arts.

Presentation do’s

There are too many books and job sites that offer hints on interviewing well to list them here. One whose style and approach I like is The Interview Rehearsal Book (Berkley Trade, 1999), by Deb Gottesman. However, you don’t need to read 100 pages to make it through an interview without embarrassment. These commonsense hints will help you support your portfolio with the presentation it deserves.

• Face your audience. Be familiar enough with your material that you can concentrate on the people you’ll be presenting to, not your screen. Avoid turning your back while you present.

• Speak up. If people ask you to repeat what you’ve said, you are probably talking too softly or quickly.

• Make eye contact. If you want to know whether you can work with them—as well as whether they can work with you—try to catch your interviewers’ eyes occasionally as you speak.

• Show interest and enthusiasm. Energy and good humor can be infectious. So can whining. Don’t complain about your previous experiences, talk about how hard it’s been to find a job, or introduce any negative topics about your past work experience.

• Be proud of your portfolio. Above all, never apologize for your work. You can discuss design, financial or branding constraints, your client’s specific requirements, or problems and solutions, but never point out what’s wrong with a piece or with your skills. That isn’t perfectionism—it’s suicide. Besides, by this time you should have eliminated from your portfolio anything that doesn’t reflect well on you.

• Hand out a leave-behind. Whether it be a disc copy of a portion of your work, a PDF extract, or a small, printed sample that evokes one of your most impressive projects, you are more likely to be remembered at the end of a series of interviews if there is something tangible in your wake. Come prepared with multiple copies...you never know who might have missed the presentation and might appreciate the chance to see what everyone else in the office is talking about.

Luke Williams is committed to doing everything right, and it shows. To prepare for major portfolio presentations in his graduation year, he printed up small flyer cards that remind the people he presented his portfolio to of his most important projects and the design story behind them.

Following up

If you are interested in the assignment or position, you should make that clear. The form you use will depend on the nature of the interaction and the position. For job or informational interviews, a thank-you note, particularly on your own letterhead or a nicely designed card, can make a big difference. But if time is important, it’s better to send an email than to take the chance that they will decide before the snail mail arrives. If the interview was for a full-time job as opposed to a freelance opportunity or a potential client, it’s also legitimate to make a follow-up phone call before you have to move on.

Finally, don’t get discouraged if the presentation doesn’t result in a job or assignment initially. Your style may not fit their current concept, or they may have found someone with more experience. Stay in touch. If you have a new collection of work in a few months, send it off to your contacts with a cover letter reminding them of who you are. Make phone calls on a regular cycle (once every six to eight weeks is reasonable) to see if there’s something new available, or if they’d like to see more work. Keep the conversations short and upbeat. If you had a PDF and have now added a website, or have significantly updated the website they saw originally, send a note to announce the URL and invite your contacts to visit it. If your work is good, persistence will be rewarded.

Staying relevant

It’s so tempting, once you finally have a portfolio in place, to treat it as complete. Many people who use their portfolio as a tool to find a new job throw it on their mental shelf once they start the new position. But very few jobs are permanent. You should clean house and freshen your portfolio on a regular cycle. If you ignore it and let it become stale, you hasten the day when your portfolio can no longer be presented. It becomes a major project once again.

The simplest chore is to check your links, if you have any. One typical boo-boo is to fail to update your mail-to link when your provider email address changes. If you link to any sites outside your own (friends, web-based projects you contributed to or designed), check every one to make sure that they haven’t changed as well. And don’t forget to check links to group portfolio or self-publishing sites. Something they think is old might be purged. Link-checking should go on your calendar as a monthly housecleaning task.

Of course, as you accumulate new projects, you should add them to your site, or replace some older ones. If you have created a modular design, inserting a new project should take very little time. The energy you invest in scanning or repurposing is small compared to the benefits of a lively, current site.

Many artists and designers include a résumé, vita, or biographical timeline as part of their portfolio. Every six months at least, you should look at these items again. Have you changed jobs, added a new, noteworthy client, or taken part in a group show? It’s much easier to add new things while they are still fresh in your mind.

In general, pay close attention to places on your site that include specific dates. When you first put them up, they can be useful markers, and in some cases, as with annual reports, listing the year is almost obligatory. But as your site grows older, the lack of anything with the current year stands out as a signpost of a dead site.

And, the end. Maybe.

With luck and perseverance, your digital portfolio will do its job and get you the recognition and clients you deserve. Once it does, celebrate! You’ve worked hard, and smart. Start your new job, or your new projects. But don’t forget the portfolio that got you there. If you’ve chosen to make creativity your life’s work, you owe it to yourself to continue to show the world your best efforts—your latest concepts. Your portfolio may change form or purpose as your career advances, but it is never really finished until you stop creating. It’s a stage in your constant journey to better work and a more satisfying career.

Portfolio highlight: Ken Loh | A hand in the game

Eventually, some creatives show a knack not only for creative concepts but for mentoring, managing, or directing the creativity of others. Their hands-on moments decrease as their responsibilities expand. What happens to the relationship between their career and their portfolio? Addressing that question says a lot about the individual. Some maintain a choice portfolio comprising every good project in which they’ve had input, perhaps feeling—with or without justification—that the work would have been a lesser thing without their touch.

Historically, those who felt uncomfortable with that approach, who felt that their staff of artists and designers really deserved pride of place, ended up with a frozen portfolio stashed in a closet. Case closed, zipped, forgotten.

Former ace designer Ken Loh has reached that career turning point. But luckily for him, the online world has redefined the concept of a portfolio, as it has nearly everything else. Being at the top of a chain has changed what he does on a daily basis. But in return, it gives him the freedom to turn his creative enthusiasms and connections into a different type of portfolio: one that advertises his continued engagement in visual issues, and provides a way to keep his hand in the game.

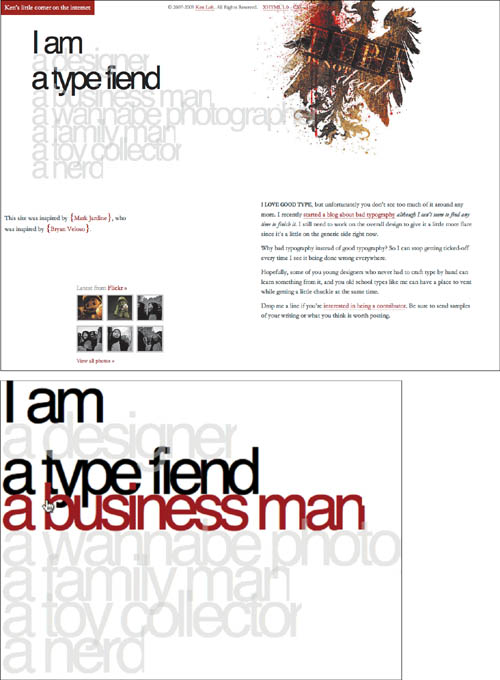

Navigation and architecture

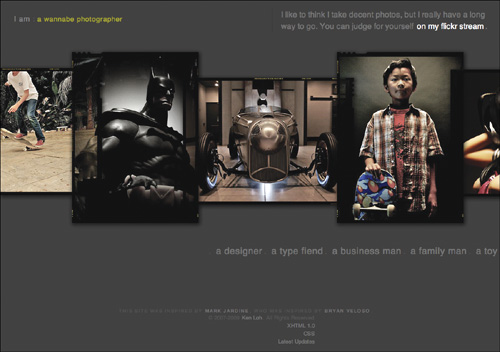

Plug in Loh’s URL, and his “Latest Updates” page appears. A literally “playful” opening displays one of a constantly rotating subset of Loh’s truly staggering collection of toys. The highly organized top of the page becomes a cornucopia of content as you scroll down. At first glance it seems chaotic, but you quickly realize that the page is actually tightly organized in a multicolumn grid. Each column holds all the most recent updates of one aspect of Loh’s busy online world.

Loh was not only a designer and art director; he was, and is, a master of website coding. His website has been featured on several blogs for its excellent design and CSS implementation. The site is built with CSS and JavaScript: a skillful compilation of feeds from all of his social networking sites, gathered in one place on the “one ring to rule them all” principle.

Loh’s navigation on the Latests page is extremely simple, yet a simple View Source betrays his mastery. The source code is very short, as it has little unique content. He has created a grid with CSS that automatically gathers everything from his tweets to his Flickr images at one address. Now that it is set up, the site requires no additional effort to maintain.

Navigation is extremely unfussy and clear. Anything red is a link. Hover over a link and it turns white. Click the link and a new window opens to the source site for the column that the link controls.

Content

Content is not only king on Loh’s site, it is the entire royal family. There are ten social networking feeds and five personal sites, each dedicated to a different facet of his interests and creative output. Like many good designers, he loves type. Among his subsites is, of course, a type blog. There’s his Flickr feed, a fascinating collection of ever-changing bookmarks. There’s even his old portfolio site, circa 2005.

In many ways, the most impressive element is the “Who is Ken Loh?” subsite. Organized by human facets, each page explores one aspect of his life.

But page is perhaps a misnomer. What look like individual pages are really parts of only a single page of code. These uniquely styled, beautiful examples of graphic design have been designed with CSS. When each facet’s text link is selected, a separate window for that portion of the page opens. If there is any question about Loh’s continued interest in, and ability to produce creatively with, cutting edge technology, this subsite should answer it.

Loh captures the elegant feel of a professional photographer’s portfolio site in his “wannabe photographer” window.

Each of Loh’s nested windows has been designed separately to capture the flavor of each facet of his life, yet they are integrated by color. The splash page is a layered, typographic image that recalls his previous design aesthetic. The Designer window has a translucent layer that slides over a collage of his work. The business man page is crisp and geometric.

Loh proves his assertion on the type fiend page. The navigation for this window is made up of overlapping text, each line of which highlights in red when it becomes active. This piece of programming is impressive, but the real surprise is the type itself. Usually, when you blow up online type, you end up with a fuzzy, bitmapped mess. Loh’s type retains its clean, crisp outlines, even at a 300 percent enlargement.

Totally in keeping with Loh’s strong sense of modesty and fairness, he makes sure that every window in this subsite also contains a shout-out to designer Mark Jardine and programmer Bryan Veloso, whose similarly aggregated websites were his influences.

Future plans

Loh has reached a career point where the likelihood of having to develop a traditional portfolio again is slim. But he’s happy with his online presence, and feels it meets his needs. Of course, when asked, he knows what he’d do if he had to clothe himself in the hands-on mantle once again. A self-proclaimed nerd, he’d experiment more with coding technologies. He has so much work, and it covers such a broad range, that he’d make a searchable online portfolio site that has links to projects by job. But most important, he’ll continue to look for the best possible people for his design team, so he can continue to lead by example.