Chapter 12. Copyright and Portfolio

Not too long ago, it was easier to call an artist and ask for permission to use their work than it was to appropriate it. Now that so many projects are digital, there is a smorgasbord of ways to borrow, sample, copy, alter, and out-and-out steal creative work. It is also harder to stay within the law, even when your intentions are honorable.

How does this affect your portfolio? In more ways than you might imagine.

A few examples: The website you designed may be copyrighted by the company that paid your fee. The photos from the royalty-free CD you used may have reverted to the copyright of their original creator. A print project that’s perfectly legitimate to display in a traditional portfolio might get you into trouble if you put it on a website if your contract says that you can show, but not distribute, the work. It’s also easy for you to be the victim of a copyright violation. Your work could turn up in someone else’s portfolio—with another person claiming credit for it.

You can’t cover every possibility without becoming too paranoid to show any work digitally. This chapter will help you become more aware of your rights and responsibilities, suggest ways to minimize your risk, and prevent you from making assumptions that could get you into trouble later.

Understanding fair use

Most copyright problems arise from a misunderstanding about fair use (see the “Terms of ownership” sidebar above). Whether your use qualifies as fair use is determined by a combination of subjective factors. Issues like intent, type of work, and the profit motive are all considered. In all cases, interpretation is key. But this interpretation is usually made with a bias toward protecting the original copyright owner. Assuming that something is in the public domain, or relying on the principle of fair use without checking on the status of a specific piece, causes trouble.

What is the work you’re planning to use? Just as some nudity is protected under the idea of “redeeming social value,” some source material—like a Matisse—is considered more worthy of protection than a less socially or creatively valuable item—like a mass-produced velvet painting.

Why are you using the work? Fair use frequently protects free speech, like when an artist excerpts a piece to make a political or social statement. Claiming free speech rights won’t protect you, however, if you use the copyrighted work of another artist whose work has nothing to do with your intended target. (See the section “Collage” later in the chapter.)

Whether you intend to profit from the use makes an enormous difference. Violating copyright of a commercial item for nonprofit or educational purposes is generally seen as being less serious than if the violator profited handsomely (or at least hoped to) as a result of the violation. For example, in 2009, Woody Allen sued the American Apparel company for using a still from his movie Annie Hall in a billboard. The owner claimed fair use, arguing that he was making a statement in solidarity with Allen. Eventually American Apparel paid Allen $5 million in a settlement. No matter what the claimed intention, the result was infringement of a well-known artist’s work in what looked suspiciously like an ad.

What about work that you’ve used “just a little”? The law considers the percentage of the piece you’re using, and how critical that piece is to the original.

When you borrow a generic piece of sky from a photograph, it’s likely that no one will notice, even though you have still violated the photographer’s rights. But if you use an image like this one, the sky is central to the concept, and your violation will be clear to anyone who is familiar with the original, or who sees the two works together.

Finally, will the owner of the copyrighted piece lose money, or the ability to market the original piece, if you use it? If your work could prevent someone from buying the original—or even a reproduction of the original—you could be in trouble.

Note that there is a big difference between copying an actual artistic creation and using the idea behind it. Neither ideas nor facts can be copyrighted—only the specific way that they are expressed.

One final consideration: Even when your piece meets all the legal tests for fair use, if it moves to the wide visibility of a website you could find yourself challenged in court by a company with a large legal department. Even if you win, it could be an expensive victory. When in doubt, don’t do it.

Respecting others’ rights

Young creatives are accustomed to YouTube parodies and illegal but ubiquitous music downloads. They know that there are plenty of sources for media online, and that, most of the time, infringement means little more than a wrist slap. So sometimes it’s hard for them to swallow the message: Using assets that aren’t yours without crediting them in your portfolio can get you into trouble. The creative community is small enough that, eventually, people who fail to respect the rights of others feel the consequences. And it’s worth considering: A person who is willing to borrow or appropriate the work of others shouldn’t be surprised if someone else returns the compliment. If your intentions are honorable, you should make an attempt to reach the copyright owner to get their blessing. Nolo Press (www.nolo.com) offers Getting Permission, a book that explains the permission process in detail, and includes any and all forms you might need to do it right.

The easiest way to go wrong with copyright issues is through incorrect assumptions. Like icebergs, a project element that looks insignificant at first glance can actually have surprisingly large issues attached to it. The following are standard creative situations where copyright issues can sneak up on you.

“Orphan” projects

An orphan project is one where the client no longer exists. There is little chance that the client is going to rise from the dead, grasping for rights with its mummified hands. But photographs or other artwork in these projects may have been purchased for limited or one-time use. Showing such work on a disc or at high resolution on a web portfolio is chancy.

Design comps

It isn’t ethical to use another person’s work in a comp without requesting permission, but it’s accepted professional practice to do so if you end up hiring the artist for the project or paying their licensing fee.

But what if you didn’t end up hiring the artist? Sometimes, a designer develops a concept, but their idea isn’t the one the client picks. Unfortunately, if the comp artwork wasn’t licensed, you can’t show the ad concept in most digital ways. If you feel the idea was fabulous and shows your creativity well, you can contact the artist directly for their permission to use it in for the limited purpose of your portfolio. You can also search for a similar image through a stock-licensing site. Prices for low-resolution versions of images are often extremely cost effective.

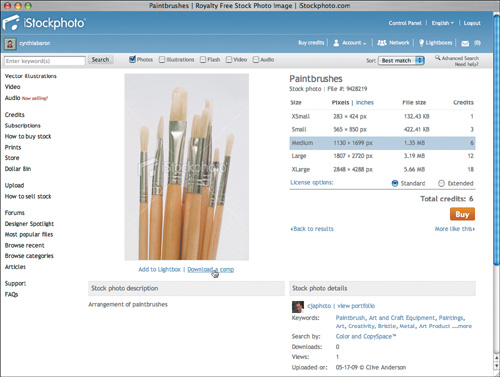

WWW.ISTOCKPHOTO.COM

You can download a comp from a stock site that will be exactly what you see in the preview: a low-resolution JPG with the stock company logo watermark imprinted on the image. But the cost of replacing the comp with a usable and legal photo is usually very modest from all but the most prestigious sites. In this case, a good-sized image for a portfolio—about 1200 pixels at its longest dimension—would cost less than $10. Some images and smaller sizes are even less expensive.

Clip art and stock sites

Most download sites state their usage policy explicitly, but not necessarily in big bold print. Usually there is a link to the fine print on usage. Read this material before you get your heart set on using a piece. There are some sites that offer completely copyright-free art. However, with a couple of notable exceptions (see the sidebar “License to share”), most provide small images meant for web page backgrounds and clickable buttons. This is low-quality art, and it shouldn’t find its way into a creative professional’s work. The general rule for a stock image: If it’s good enough for you to want to use it, it’s probably someone’s licensed work.

Usually, your license-free rights on a stock image are limited to low-resolution versions of the work. Otherwise, there is a payment structure based on the size and resolution quality. What if the downloaded work is presented on a project that was clearly just a comp? If the work came from a stock site and you are only using the comp-sized version, there is no reason not to use it in your portfolio. Of course, that comp version probably has the stock source’s watermark prominently displayed across the image. If you don’t want that as a distraction on your work, you will have to pay at least the minimum cost of licensing to replace it with a clean image.

Bear in mind that this book’s discussion of copyright is geared toward the use of these stock images in a personal project, or for a typical client project that you would eventually want to display in your portfolio. For anything else, be sure to read the fine print on usage. You’ll discover that most of them explicitly prohibit using their images on products for resale. You can’t use them in a logo, or put them in any form on a T-shirt or self-promotional piece that you might offer for sale on sites like Cafe Press (www.cafepress.com) or Zazzle (www.zazzle.com).

Collage

Collage involves not just the collection of images, but their careful extraction, composition, and alteration. It doesn’t seem fair that practicing a respected form of art could get you in hot water. But even without the added complication of a digital image, collage can run afoul of copyright laws.

For example, in 1991, Robert Rauschenberg incorporated a photo of a car from an old Time magazine into a collage, and was sued by the commercial photographer who took the photo. Mistakenly, he viewed the decades-old work as “found” material. Students often do the same, scanning elements from magazines and books. The sources frequently are an important element in their composition. Anyone who appropriates materials from magazines and design annuals could someday present their portfolio to the very person who created the source art.

Derivative art

“Derivative” art is work that is based on someone else’s creative output. The Copyright Act clearly states that only the original work’s copyright owner can copy, duplicate, reprint, alter, or adapt it.

What about the “gray area,” where you think you’ve altered the piece to such a degree that it qualifies as new art? The law takes a commonsense approach to these actions. If you pluck a person off the street and show her both images, would she recognize them as being similar? If so, no matter how you’ve changed the work, you have violated the law.

Sometimes the medium you select for your derivative art affects its usage. Many artists use art classics for inspiration, or as a starting point from which to comment on or satirize the work. When appearing in a painting or other one-of-a-kind work, the use can be perfectly legitimate. But a reproduction of the same artwork that could be downloaded and printed—like a piece of your online portfolio—might fail the rights test. Even if the work is supposedly in the public domain, it may be owned and licensed by the museum where it’s displayed. See “Terms of Ownership” above for information on how to determine the status of a work you want to use.

Derivative style

There is a big difference between adapting an existing artwork and working in the style of another artist. Working in someone else’s style can be an homage, particularly if the artist has historical relevance and the work is not a copy of any existing work. It can also be a way to get the superficial benefit of a distinctive look without having to pay the original creator. Copyright law has no way of protecting the original artist or designer in either case.

For example, one of the best-known graphics from the late ‘60s is Milton Glaser’s Bob Dylan poster. If you scan a copy of his poster, change the colors in the hair design, and straighten Dylan’s nose, you have done more than use an idea. You have created a work to replace the original and have violated Glaser’s copyright.

On the other hand, if you came across Glaser’s work and it inspired you to create a totally new graphic combining a solid color form and strips of curved, stylized lines, a savvy viewer will recognize that you are working in Glaser’s style, but you are legally clear.

Creative influences

Unlike derivation or collage, there are no negative ramifications if you have been influenced by the ideas and work of another. Even Einstein gave homage to those who came before him by saying that he “stood on the shoulders of giants.” In fact, acknowledging your influences in your portfolio, although still rare, is becoming a way to show your awareness of your creative domain’s history and heroes. A shout-out or short mention of an influential teacher or mentor can even be a way to start a dialogue with potential collaborators or employers.

WWW.TRIBORODESIGN.COM

Triboro’s partners feel they owe designer Alexander Gelman a particularly important acknowledgment for being their mentor. They show examples of his work and link to his site. In their About section, they also acknowledge their collaborators. As David Heasty says, “I think these full disclosures of influences are very interesting to people. I would love to see more designers embracing this transparency.”

Roles and large projects

It can be very exciting, when you have worked on a project for a well-known brand or taken part in a major campaign, to include the project in your portfolio. Before you do, be honest with yourself about your share in the work. Were you the art director, or a junior designer? Did you develop the concept, or only execute the production?

It’s always better to present your share of the project honestly. Everyone knows that major projects are the work of many minds and hands. If a project is great, taking credit for only your share will reflect well on you. Giving credit to those who earned it will prevent confusion when more than one team member applies to one firm or deals with the same placement agency. Not only will you be better prepared to speak about the portion of the project that you know intimately, but you will be spared the embarrassment of being confronted with any gap between reality and your presentation. See Chapter 11, “Portfolio Reels,” for ways to specify your roles and to offer credit to others on a team.

Owning your work

In a surprisingly large number of cases, even when you create all your own material, you don’t own the copyright to it. The circumstances under which a work was created determines who owns and gets to license it. This can have profound implications for a digital portfolio, which by its very nature involves copying and adaptation. It has particular financial implications for illustrators and photographers. If you maintain rights to your work, you can recycle an image into the stock-image market, making your portfolio a potential income stream.

If you have created an image on your own time, for your own purposes, it remains yours to duplicate or change. Even if you sell the original artwork, you can retain the right to show copies of it in your portfolio, no matter what form that portfolio might take. If you choose to make a series of unique images in the same style, on the same theme, or with elements from the original, you are still free to do so.

On the other hand, work you do might conceivably belong instead to your employer, your client, yourself in combination with one of the above, or a third party entirely. One key to this distinction can be your legal working relationship with the other parties.

Employee or independent?

Were you an employee when you created the work? Did you do the work while having taxes deducted? Did you have a supervisor? If so, the work belongs, and will continue to belong, to your employer. You can certainly claim that you did the work, and probably show a printed copy of it, assuming that trade or non-disclosure contracts are not in effect. But you can’t copy it, sell it to someone else, or adapt it for a freelance job. If you want to use the work in a digital portfolio, you will need to get permission in writing from your employer to do so.

A freelancer is considered an independent contractor if you use your own materials and computer, work at home (or not regularly at the client’s office), set your own hours, and get paid by the project, not by the hour. Unless there is a contract stating otherwise, the freelancer retains copyright on the artwork, and the client simply has rights to use it. The nature of that use (how extensive and broad) should be negotiated at the beginning of the project. The independent contractor has every right to reproduce this type of work in portfolio form.

You (or your employer or client) can’t have it both ways. If you want to retain rights, you can’t also get the benefits of employment—sick days, health insurance, overtime, and so on. Conversely, your employer can’t deny you these benefits by calling you an independent contractor unless they also let you retain your copyright.

Work-for-hire

In a work-for-hire arrangement, an independent consultant is paid to design, create, or produce something for a fixed sum, selling their rights to the work to the person or company who pays them.

Work-for-hire is a growing problem for creatives, who can end up with large chunks of their creative output belonging to someone else. An old-fashioned portfolio—where one copy of a finished work was carried around, shown, and returned to its case—almost never prompted a legal action. The existence of digital artwork—infinitely and immediately duplicable—has changed that, and made the work-for-hire provision in a contract an increasingly ugly by-product of doing business.

What qualifies a commissioned freelance project as a work-for-hire? A surprisingly broad category of work:

• A contribution to a “collective work”—a large corporate website, a newspaper or magazine, or an encyclopedia.

• Something that’s part of a motion picture or other audiovisual work—like character animation, modeling or lighting, or contributions to an interactive CD or its storyboards.

• A translation, a test, or answer material for a test.

• Instructional text—a textbook or training package.

The language in this contract clearly states that the artist is selling the rights to his work on this project.

• A “supplementary work”—everything from maps and tables to indexes and bibliographies.

• A compilation—like a database or bookmark list.

If you’ve been looking for a common thread, you may have noticed that the law assumes that the work would not have been made without the larger project, and that the work would not necessarily stand on its own. On the other hand, both parties have to agree in writing that the project should be considered a “work made for hire.” Any item that both parties put their names to that calls it such is considered a binding contract. The phrase has, therefore, been known to be tucked into a work contract and printed on the back of payment checks.

Assignment of rights

As a freelancer, try to avoid being pushed into work-for-hire. You are being asked to give up more than the time you spend creating the work, without any employee benefits and protections. At the very least, negotiate for rights to display the work in your portfolio when you and the client draw up a contract. The contract should state your intent to assign the rights to the client after the work has been completed and paid for in full. This differs from a work-for-hire because the two of you can write the specific provisions necessary to give your client the rights they need to use their material without denying you the right to claim your contribution.

A perfect example of why an explicit exemption for portfolio purposes is so important is the animation portfolio reel. By and large, unless the animation in question was designed, developed, and executed by and for one person, or by one team of creatives with no third party (like an ad agency) involved, getting rights to display your work after the fact is likely impossible. There are too many layers of individuals and teams of lawyers between you and the final client.

If you stamp a big copyright C over the image, you are certainly safe, but you also degrade the quality of your work, often to the point that people fail to look at it carefully.

Almost every animator puts excerpts of these projects into their reels with the probable assumption that no one will chase them. That is true...until you place the work on YouTube or another public site. Some large corporate clients—exactly the companies whose work it would be valuable to show—are the most vigilant in maintaining their rights.

Teamwork and individual rights

With the growing need for groups of people with different roles to work collaboratively, it becomes more important for the artist or designer to document such involvement. From the beginning, your contract should clarify the scope of your involvement. If you will be responsible for a project section, or a specific group of illustrations or layouts, keep copies of your process work. If, as sometimes happens, you are called upon to handle more material than was originally planned, make sure that the change is also documented, not just to make sure that you are appropriately paid, but so you can ask for rights to show the material.

Protecting your work

Any time you provide an image at a resolution or in a format that would allow the work to be edited or printed, you could become the victim of art piracy. Besides threatening to sue, and then really doing it, what can you do to protect your work?

Copyrighting

In the U.S. and Europe, copyright is implied without the need for a symbol or any registration. However, you can’t sue for copyright infringement without registering the work. In the U.S., you have five years after you create something to register. If you register before a copyright infringement—particularly if you did so within the first three months of the work’s creation—your chances for winning a case are higher. You can register your work online for $35 (www.copyright.gov/eco/index.html) by filling in the form and uploading a copy of your work in an acceptable file format. There is a complete list online, but it is exhaustive and covers all major formats in a variety of media types. This is by far the fastest and easiest way to register, and the one with the shortest government processing time. Although it will still take from two to six months to receive a certificate, you are covered as soon as the Copyright Office receives a complete and correct form.

A U.S. copyright is valid in most other countries, so you don’t have to worry about taking out additional copyrights to show your work on the web, or to send it to people in other countries. If you are in the U.K., copyright is considered automatic and you don’t have to fill in a registration form. However, there is a useful PDF with relevant copyright information at www.ipo.gov.uk/types/copy/c-about.htm.

Using the copyright symbol with your name can stop innocent appropriation. The proper format for doing this in the U.S. is:

Copyright © 2010 Your Name. All rights reserved.

However, any statement on your web portfolio that clearly states your copyright is considered valid.

Luke Williams displays his copyright in shorthand as part of his nav bar. It is present at all times, and on all pages of his site. Jonnie Hallman, who programmed his site, used code to make the copyright for his portfolio update automatically when the year changes. That way, as the portfolio is updated with new work, the most recent edition of it is recognized.

Protection technologies

The most common way to claim copyright on a digital image is to simply add the copyright symbol and information directly to the piece. Although more than adequate warning for the well-intentioned, this is not much protection against anyone with a good eye and a cloning tool, especially since you can’t put the notice anywhere that is critical to viewing the work.

One compromise between paranoia and laissez-faire is to provide low-resolution images. An image large enough to represent your work onscreen but well below printable threshold prevents someone from easily “borrowing” your work. However, this is a less useful solution than it used to be. It doesn’t prevent a determined or clueless violator from copying your image and using it in low resolution. And it negates one of the most critical reasons for putting your work online in the first place: to display it in the best possible way. Most portfolios are showing big, beautiful images, but they do so safely by making technology work for them. There are several options to help show your work in all its glory:

• Adobe Acrobat PDFs. PDF files preserve font, format, and color decisions for artwork that combines type and image. (See Chapter 4, “Delivery and Format,” for more about PDFs.) If they’re not password-protected, anyone with Acrobat Professional can extract text and images from them. Fortunately, it’s easy to lock your PDF in Adobe InDesign, the software that most designers use to create multi-page portfolio PDFs. After selecting File > Export and clicking the Save button, you’ll see a small column of options on the left side of the dialog. Select Security from this list of options. In the Permissions section, check the check box to require a password, and type a password in the field. Uncheck “Enable copying of text, images, and other content” to prevent your work from being copied or extracted.

You can prevent the materials in your PDF from being copied or extracted by changing the defaults in the Permissions controls. To be even more secure, you can limit the changes allowed to Commenting. That way, team members of a potential employer can still share one copy of your work and point out specific projects that interest them.

• Player software. Players make your work portable. Although it is possible to extract material from a player file, it is very difficult, and usually far more work than it’s worth. Flash SWF files are the preferred players for interactive portfolios. If you are concerned that someone might download one of your SWF files from your site and repost it elsewhere as their own, you can easily disable the right-click context menu. Before you create the SWF file, just visit File > Publish Settings and select the HTML tab in the dialog. Uncheck “Display menu” in the Playback section.

• Watermarking and digital “signatures.” Some programs allow you to imprint sound and image files with invisible digital watermarks—methods that hide identifying content inside the digital data of a file without changing the look or sound of the file. This embedded data makes it possible to prove ownership of an image, even if someone makes major alterations to the original.

Dealing with infringement

Anyone who has ever found their work passed off as someone else’s, or has seen a portion of their art looking back at them from an unknown source, knows the feeling of personal violation. The reaction, after the shock passes, is to DO something about it. But what?

Your legal rights

Copyright law states that you are “entitled to recover the actual damages.” This means that you can get the money you should have been paid, including any net profits that the infringer made through the use of your art. Though it may be tempting to overestimate the damage, assign a realistic dollar value to your artwork and the effect of its loss. If you have been getting a few hundred dollars an image, suddenly claiming $10,000 for one won’t be believable.

If your work accounts for only a small portion of the piece (one design element in one screen of a CD, for example), the profits will be prorated accordingly. Even so, if the project was lucrative, you could be awarded statutory damages, in addition to your legal fees. Statutory damages can punish a deliberate infringer more seriously than actual damages.

On the other hand, few infringers nowadays are major corporations. Large companies have departments responsible for tracking and getting releases for art, precisely to avoid this type of issue. Most likely, your infringer is not making any money from your work. If there is little or no financial impact and no damage to your reputation (particularly if the violator clearly thought they were operating under fair use), your time might better be spent educating the infringer.

Acting effectively

Even if you have access to unlimited free legal help, try to deal with the situation yourself first. The law can be unsympathetic to an action that might have been settled amicably out of court. Send a certified, business-like letter (not a hot-tempered set of empty threats) to the infringer. Let them know that you’ve discovered that they are using your copyrighted artwork without your permission. Describe the work clearly and give the date the violation was discovered. If the violation took place on a website, make it clear that the infringer must stop displaying your work immediately. Then send them an invoice with a realistic usage fee, and a deadline before you take action. You may receive a shocked and contrite phone call, a request to work something out, or an apologetic note with a check attached.

If the violation was online, you can bolster your case with solid documentation by visiting the Internet Archive Wayback Machine (www.archive.org). They have archived websites from well into the Internet’s prehistory (1996!). Search your site for the first instance of the violated work. Do the same for theirs. With luck, the archive has the page or pages in its database that will allow you to prove that your work existed first, and that theirs is the copy.

Assuming your documentation is in hand, and the infringer is not responding, you can up the ante by contacting their Internet service provider. They may find it in their best interests to exert pressure on the violator by shutting down their site. Under certain circumstances, Google may come down on your side by removing access to their site from their search engines—tantamount to taking down their site, since, without search access, in practical terms they will no longer exist.

If you’ve decided that legal action is your only option, search for a lawyer who knows intellectual property issues. If your infringer stonewalls, or you receive a corporate “up yours” letter—and if you’ve decided that the $1,000 or more cost is worthwhile—your lawyer will file a cease and desist order against them. Make sure your lawyer makes every effort to settle the case out of court. Even if you get less money than you think you deserve, anyone who has ever spent time in the court system will tell you that the wheels of justice turn slowly, when they turn at all.

You may decide that you can’t afford to go to court. If the infringer is a professional, and they have chosen to stonewall rather than apologize or negotiate, call in your social and professional networks. Speak to relevant guilds and associations. Some of them have funds set aside for copyright actions. If the work has been used to create a commercial product, contact the client directly. Send a cover letter with a clipping of your stolen artwork. Ask them to compare it to the non-original art and judge for themselves. Sometimes public shame will do what good conscience will not.

Portfolio Highlight: Noa Studios | Fair share

A portfolio is one place where you can unabashedly trumpet how good you are. Sometimes that freedom leads people to claim more involvement or input in a project than they actually had. They fail to mention that their input was a team effort, or that some artwork they used was created by someone else. Critics tend to blame the young for the worst of this lack of attribution. And yet, the portfolios of young artists and designers are where you most often see overt collaboration, along with exuberant pages of thank you’s and shout-outs to those who have shared their work.

One of the most delightful examples of this open-handed, go-for-it attitude is the Netherlands-based Noa Studios portfolio site. The result of a pairing of creative opposites—project director and artist Pascal Verstegen and web designer and Flash programmer Emin Sinani—the site bends many a standard portfolio rule, and does so with enthusiasm, élan, and some serious skills.

The Noa site opens with a short 3D animation of their logo, establishing their aesthetic and their major visual elements. Although you are welcome to skip the intro, at normal cable speed it is barely 3 seconds long, which is very impressive given the window size of the video.

Architecture and navigation

With so many creatives posting their work online, it’s a constant struggle for newcomers to find ways to be noticed. Noa’s site was the result of its partners being challenged to enter the 2008 edition of the annual May 1st Reboot web design contest. Despite having never entered before and being among its youngest participants, they walked away with top honors. Not knowing the “right” way to do something, coupled with boundless energy, can sometimes lead to surprising results. In a contest that looks for innovative new ideas in web design and interaction, Noa stood out.

The scroll wheel begins as an iPod clone, in an environment where mimicking a rotatable physical wheel is extremely difficult to do. The wheel performs elegantly at any scrolling speed as it acts like a radio dial along the linear bar to bring up each of the main navigation choices.

The white iPod skin morphs into a stylistic echo of the Noa logo when you use it to navigate through a portfolio category. As with any video player, clicking the arrow starts a video slideshow of each portfolio group. A counterclockwise white marker provides visual feedback.

The most striking element on the site is their main navigation: the iPod-like scroll wheel at the bottom of the frame. Using it moves you fluidly between their main portfolio areas with an effect that is surprisingly realistic.

Stylistically, the scroll wheel drives the look and feel of all other components: their portfolio thumbnail build and even their site’s version 8 logo are driven by circular motion. Although Noa provides alternative navigation (a small standard nav bar at the top of the window and selectable menu text at the bottom), everything on the site is readily available from the scroll bar, which requires very little arm and mouse movement. The click and hold navigation is just as smart on the website as the original concept is in Apple products.

Content

Select a portfolio area, and a grid appears onscreen. Images in the first stage of loading are indicated first with Noa’s signature counterclockwise circle. They are quickly replaced by transparent thumbnails of the work, whose resolution and substance increase until the grid is fully populated.

From the beginning, Verstegen and Sinani viewed the site as an exploration in user experience. They wanted to provide designs for a wide range of applications, from logos to websites to desktop skins. However, although they definitely appreciate each other’s work, they come to the table with very different instincts and talents. Verstegen has mastered Flash programming, but is most interested in graphic art, trendwatching projects, and “useless” but richly entertaining interaction. Sinani is a devotee of minimalist design and functional interaction. The result of their creative push-pull is, as Verstegen says, “the middle path that makes something everyone can enjoy and that we both love.” You can easily see that in their website. They compete and collaborate equally well, and with the same intensity.

Select the Info button at the top of each framed portfolio piece, and a balloon appears to the right of the work identifying the main partner involved, or specifying that the work is a Noa Studios collaboration. In these two representative projects, Sinani (nicknamed Zunamo) was responsible for the top project, a website, and Verstegen (nicknamed Enkera) was responsible for the bottom project, a desktop skin.

The biography section not only introduces Noa’s partners, it thanks people who helped them add features, like the streaming video and site music. The map to the right offers thank you’s to contributors, pointing out the global reach of their collaborations.

Unlike most studio sites, they clearly label each work as a Noa Studios effort, an individual project of one of the partners, or a piece created with an outside collaborator. This labeling makes it easy to recognize what each one brings to the table when they combine forces.

Future plans

Although they are both basically happy with their current site and feel that it met their goals, it won’t be long before Noa Studios morphs again. They have received a tremendous amount of feedback on their site, far more than they would have without putting themselves so boldly into the online mix, and it has helped them toward new ways of thinking about their futures. In addition Sinani and Verstegen are excited and enthusiastic about the addition of new features, like a blog and new video options.

Noa’s principals are students, at the beginning of their careers and with a long creative life ahead of them. They see every iteration of their joint portfolio as an opportunity to apply the new things that they are learning. Because their work is driven by a desire to hit new technological levels, their new site will be redesigned and rewritten from scratch. The one thing that is certain is that the two partners will continue to use their web presence to bring them a bigger network of collaborators and more recognition.

Could this be the new version of the Noa Studios site? Their site is always a work in progress, full of possibilities and connections.