Chapter 11. Portfolio Reels

The demo reel holds a special place in the portfolio pantheon. It can be both content for a portfolio or stand on its own as the portfolio.

In either case, the reel is an object whose form, format, and rules of play are very different from that of the normal web or disc-based portfolio.

The exact purpose of your reel—content, audience, artistic specialization—affects its guidelines for planning and development. A reel for an animator interested in game development will probably contain different content than one interested in 3D modeling and lighting for feature films. And the reel of any animator or game artist will be different from that of a game developer, and radically different from that of a video or film editor or director.

Although the specifics for each artistic discipline can trip you up if you aren’t aware of them, there are many guidelines for designing and developing that all reels share. In this chapter, I explore what makes a good portfolio demo reel, how to tweak reel basics for your own type of content, and how to avoid the things that guarantee your reel a home in the circular file.

Reel possibilities

Unlike other portfolio artifacts, the reel is sequential, just like the tape reel (and then the VHS cassette) from which it takes its name. A viewer might fast forward, but usually won’t skip back and forth. The linear format offers much more opportunity for control—and showmanship—than other digital portfolio forms.

The reel format can also be the proverbial rope long enough to hang its maker. The standard of excellence has risen steeply with the move of the portfolio reel to a digital format. If the reel presentation is just adequate, it will devalue all but the most extraordinary work because it will be up against reels that actively support their individual project clips.

The single most important thing to remember as you build it is that the demo reel is not just a nice collection of clips. It is an exercise in personal branding. Here’s where your soul-searching from Chapter 1, “Assessment and Adaptation,” must pay off.

Your reel and the market

A trained graphic designer may specialize in corporate identity, but can express that specialization in more than one medium, as great portfolios containing both print and online projects prove. But in the moving image professions, there is much more granular skill specialization.

Particularly when it comes to animation and gaming, technology has taken what was already a highly-segmented set of jobs and sliced them even thinner into hundreds of niche production jobs. If you’re a 3D animator, you’ll first be confronted with a selection of major job categories: character animator, modeler, compositor. From there, you may have to parse finer, into some combination like 3D modeling and lighting, or lighting, texturing, and rigging. The game world is even more complicated, since it encompasses not just game artists, but game designers and game developers who may be visually talented as well.

But the irony of these narrow job descriptions is that all but the biggest studios use them to specify what they need in a freelancer for a single project. For a full-time position, the most desirable person is the generalist—someone who can wear several hats equally well: model a character one day, light a building another day, and design a new character the following week. So the ideal portfolio reel—particularly for someone who is just starting out—has to demonstrate deep proficiency in at least one important skill while also indicating broad creativity and talent in related ones.

That’s a tall order, and hard to nail perfectly. Talented graduates from the same program in game art and design may have radically different experiences in landing a job, depending on the mix their reels display.

Obviously, the deck is stacked in your favor if you are a multitalented generalist because you can fit yourself to a wider range of positions. However, if you’re significantly better at one role than most of the others you could apply for, it doesn’t matter if there are more jobs for generalists. Narrow your emphasis to your strongest suit and you’ll increase the chances of getting your foot in the door.

Developing the reel

The reel has many of the goals, limitations and requirements of a movie trailer. In a very short time, it has to pull in the audience, keep them engaged, and make them want more. Even a momentary lapse of tension can break the spell.

You’ll need to plan your reel carefully to make it past the levels of gatekeepers to the people who will actually make a hiring decision. You have a better chance of hitting that sweet spot if your material is unbelievably great. But few people are so amazing that they’ll be hired no matter what. For the larger number of people who are good or really good, the goal is to create a reel that will move the perception of their work up a notch.

Reels are probably the most time-intensive type of portfolio to design and develop, including the portfolios of multimedia specialists. Even when you take that as gospel, chances are that you will spend infinitely more time creating your demo reel than you expect. No matter how organized you are, set aside several weeks before your due date to have the luxury of recutting and tweaking as you get feedback and rethink your decisions.

Reel length

As with a regular portfolio, the first questions anyone asks are how many pieces to include, and how long a reel should be. The number of pieces is less of an issue than length. Unless you have a remarkable history of high-profile projects, your demo reel should not run longer than two minutes. Arguably, even that is too long; some great demo reels are considerably shorter than that. You have a maximum of 30 seconds to excite, and even less if the viewer sees anything—even something minor—that they strongly dislike.

Selecting highlights

Like any other portfolio, the rule is: only your best stuff. However, the format of the demo reel gives you the opportunity to cherry pick. Maybe you have a fairly early project with flaws, but that also included some great short bits. In a demo reel, you won’t have to show anything but the little gems. The same is true for a piece you’ve been working on in your spare time but haven’t finished. No one will wonder whether the project the clips came from was complete, unless they are so impressed with your reel that they start searching your portfolio site for it. And by that time, you’ve probably grabbed them anyway.

Go through your work looking only for the highlights, particularly those that support your expertise in your chosen area. If you are a film editor, for example, you should highlight the way you juxtapose two types of material, maintain perfect continuity, or cleverly recut a scene to create a subtext. If you are looking to break into 3D animation, you’ll want to show proficiency in texturing and modeling. For work in game animations, clever workarounds in low-poly environments and good 2D work are important.

But these are only broad categories, and can change year to year as new features are added to software packages. One of the best ways to figure out the types of skills that are currently in demand is to look at the reel submission requirements for companies you’d like to work for. In many cases they will be quite specific about what techniques matter to them. Of course, you always have to remember that such guidelines will only give you a sense of in-demand technology, and that everyone who pays attention will have seen the same lists. It’s still your game to find the expressive and creative ways to meet the technical basics that will make your reel memorable.

Variety

Within the highlights of your best work, look for variety. Part of what makes a good reel is a broad mix of styles, types of projects, and subject matters. Variations in pacing can be particularly useful, because they can help you establish a rhythm and prevent visual sameness from overtaking your reel. If you are working with documentary film, for example, you should look for places where you’ve captured strong emotion or facilitated a great dialogue between two people so you can mix up lively, external moments with intimate scenes. Nothing is more deadly in a reel than pieces of six projects that are good individually, but that when excerpted and strung together feel like a wall of gray sameness.

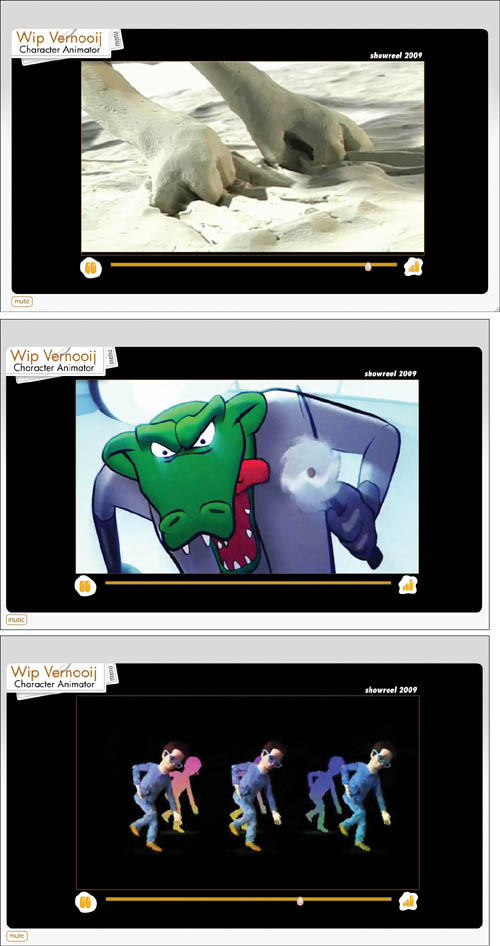

WWW.WIPVERNOOIJ.COM

Vernooij is a 2D character animator who shows his variety in style and character type with his demo reel choices. The first clip is from a claymation project, the second from a personal 2D animation, the bottom, a character designed for a Flash game.

Variety is important, but not all clips are equally appropriate for your reel. As with any other portfolio, avoid explicit violence, sex, and bathroom material.

Unifying idea

As you rethink your work as a series of short moments, you should be looking for ways to smoothly connect your clips. There is no single right way to do this. Some people concentrate on visually linking to and from each clip in the sequence. You can make those links with subject, position of main objects in the frame, color, and direction of movement. Or more subtly, you can use pacing and music to create a mood. All the great cinematographers and directors find ways to cut between two disparate shots while maintaining continuity, and so should you.

If you are a good storyteller, you have a powerful plus in developing your reel’s structure. You can create a unifying idea and use it as a thread to sew your reel together. Some refer to this unifying reel concept as a theme. However, many people misunderstand the term and take that to mean a visual style, like a desktop skin. That’s the opposite of a concept theme, because it is an unrelated element grafted on top of the work rather than having a true connection to it. A real theme helps to put your work into perspective by making disparate projects feel that they belong together.

You can find a unifying theme from within the clips themselves. For example, you can use a character or object as an MC. Or you can create playful opening and ending screens that place the viewer in a frame of mind or environment: an airplane, a beach, in 1920s Paris, or in an alien dinner theater.

Structure

Your reel structure is really very simple. The reel is “just” a collection of clips drawn from a variety of material, techniques, and challenges. Your objective is to mine your body of work and provide the viewer with an expansive impression of your imagination, knowledge, and abilities.

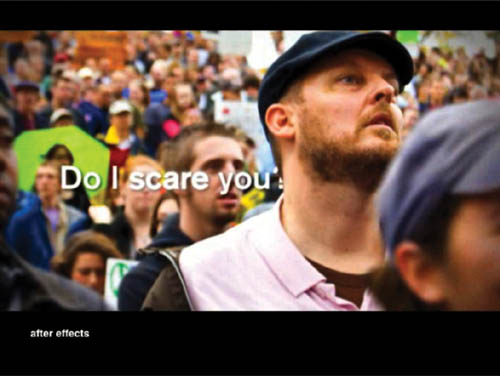

WWW.WIPVERNOOIJ.COM

Vernooij unifies his reel presentation by creating a little character who introduces his portfolio reel, then returns at its end to wrap up and provide his contact information.

The opening is a very important part of your reel, no matter what your specialization. It sets the mood and gives your audience a moment to focus their attention. You can provide that settling-in moment with something as simple as a nicely designed static titling screen, or something more ambitious, like a bumper.

Bumpers are pretty much what they sound like: a little something that protects two different things from uncomfortably smashing into each other. They are a very short sequence of frames—one to three seconds is sufficient. If you are having problems transitioning between two otherwise disparate clips, creating a bumper as a transition and sandwiching it between the two might solve your problem. Bumpers can also be a lifesaver when you are cutting your work to music and you are just a few frames off hitting a downbeat or the end of a musical phrase.

Sequencing and flow

Sequence your work by placing all your clips into one place, and select two of the very best as bookends. You want to start with something terrific to capture the viewer’s attention and get them on your side, and end with something astonishing or moving that can reverberate in the mind long after they’ve viewed your reel.

The devil is in the details, and that’s the big center area. Don’t put anything mediocre between the two gems. Padding hints that the first great clip was a one-hit wonder. But you can ratchet the intensity up and down. A great example of a wireframe from a low-polygon model may not be exciting, but the quality of your craft may be just the right counterpoint to lead into your next fully rendered clip. For a video artist, use your selections to create an umbrella narrative arc, with an opening, a couple of rhythmic changes, and an impressive closing piece to bring it all together.

Keep each piece of content just long enough for the viewer to get the gist of the action. The mix of types of work should be as unpredictable as possible: Jump as quickly as the material allows from one clip to the next. It’s often better to use different parts of a single project as glue over the course of the reel than to graft long pieces together. If you have a great long piece, you can graft a few cuts back together as a minitrailer segment, or use pieces of this work as a thread throughout the reel to support other material that may not be as exciting but that illustrates an important skill.

Once you have a sequence in the rough stage, play it through and examine it critically. It’s unlikely that you’ve nailed your sequence at first try. Treat your clips like playing cards in a game of solitaire: Swap them in and out for the best visual transitions.

Music and timing

In many ways, music may be the most important single element in your reel. Every director from Hitchcock on down has demonstrated how critical sound is to a movie experience. It’s likely to be a major contributor to your portfolio reel as well. The right piece of music will provide you with a mood or attitude that perfectly captures your work’s personality.

Music also helps you through that critical last point after sequencing: timing. One of the most obvious failings in a reel is clips dragging on too long. And in a reel, too long can often be measured in fractions of seconds. The rhythm and punctuation of music gives your clips a structure to follow. Music is a form of narrative, with a convenient beginning, middle, and end. Combine a brilliant flash of light with a sudden, crashing guitar chord and both effects are amplified. Because music has phrases, clips can be cut at exactly the point where one phrase ends and another begins. Your end result is stronger, more dynamic, more magnetic.

That being said, music is also a potential red herring. Because it can smooth over rough spots and create enormous energy, it’s very easy to gloss over deficiencies in your reel simply because you don’t see them...you’re too busy bouncing along with the beat. You can only hope that your audience is, too.

Problem is, they may not be hearing the music at all. In large companies, the first people to vet your reel will probably be those in the HR department. People hired for these positions are chosen specifically because they have experience with creative departments. They aren’t expected to make final decisions, but they do have enough sense for what the final decision-makers want that they can be trusted to handle the first cut. By and large, they do that by gathering in a conference room and watching the reel with the sound off. If your visual presentation isn’t good enough to stand on its own, it will become obvious to them quickly.

The only way to ensure that the music doesn’t blind you is to turn it off yourself. If you’ve used it well, the sense of rhythm and the build in pleasurable tension should have transferred itself to the reel. You’ll miss the music, but not enough to ruin the enjoyment.

The other time when dependence on music can hurt you is when you use a self-publishing site as your portfolio reel’s home. Unlike on your own address, where it’s unlikely anyone will notice or care, these sites are big enough to be sued. YouTube, for example, will take down a video that infringes on a company’s copyright if they complain, or if someone else points it out. That’s most likely to happen if you use a popular idol’s music for your reel. Or perhaps they’ll simply block the sound portion of the feed. For some reels, that’s not much better than being blocked entirely.

Audience sweeteners

After you have your clips sequenced and timed exactly as you want them, it’s time to consider those seemingly small details that wrap up the reel package and telegraph that you are an experienced pro—even if you aren’t quite that yet. Adding the following elements to your reel shows your sensitivity to who will be viewing it, and under what circumstances:

• Sound level test. Every reel with sound should contain a brief audio test tone at the very beginning. This tone may be a nicety for funky jazz, but a necessity for heavy metal. Every playback device for your reel will be set to a different volume, and the last thing you want to do is explode the eardrums of a potential employer. Sure, they’ll adjust the volume when your music begins, but it’s a guarantee that they will utterly miss whatever is actually onscreen for that time. Since its likely to be one of your best bits, you want them totally focused from the beginning.

• Color bars. Like the sound test, placing SMPTE color bars at the beginning of a reel is a leftover from the days of tape, and many digital reels no longer include them. That’s a shame, because they’re just as necessary now as they were then. Not all viewers have a calibrated monitor or projector, but they all know what a color bar test should look like. If the colors they see on the bars before your reel are off, that’s a good hint that they will not be seeing the reel as you designed it. Hopefully, they’ll make adjustments. But if not, at least they’ll be aware that those orange faces are not the result of your visual limitations.

WWW.COMFORTKYLE.COM

Kyle Raffile turns the color bar into a clever bumper animation. Finding a way to make even a dry requirement into a visual treat is one strategy to make a jaded reviewer sit up and take notice.

• Credits. As you’ll see in Chapter 12, “Copyright and Portfolio,” claiming only your own share of a project and giving explicit credit to others is non-negotiable. Identify clearly any collaborators or team members. Credit the music and any other elements you did not create yourself.

WWW.FISTIK.COM/CEMRE_WEBSITE/

Cemre Ozkurt identifies the work category in this clip—character modeling—with a brief label in the lower left corner. He also prompts the viewer to match the code number on the right against his reel breakdown. This clip was part of LA-based Blur Studio’s 2006 animation “A Gentlemen’s Duel.”

• Labels. A discreet MTV-like label in one corner of the screen can serve many purposes. Because it travels with and is seen at the same time as the clip itself, it can immediately end-run the question, “What part of this project was her responsibility?” If the answer to that question is too complicated to fit on the screen without distracting from the work, at least use the space as a key matched to your reel breakdown.

• Contact Info. Most people do remember to put their name on their reel’s title screen, but a significant number fail to put their contact info there as well. How will anyone reach you without it? In fact, your contact info should be both at the beginning and the end of your reel.

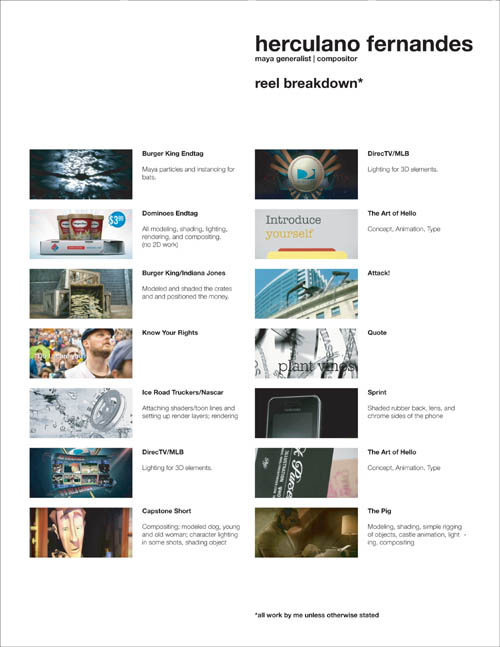

• Reel breakdown. Even if you label your clips, you’ll still want to provide a reel breakdown. That’s a separate document that identifies each clip that you used in the order in which you used it. The reel breakdown is also the place where you clearly identify exactly what you were responsible for, in whole or part. For example, if you only modeled one character or a few objects, you need to identify and claim credit only for those elements. Ideally, you’ll want to brand your reel breakdown to match the reel itself, using the same typefaces and general design feel so it’s clear that the two pieces belong together.

Reel delivery

Once you have designed and sequenced your reel, you need to finalize it in player form and get it out into the world. See Chapter 7, “Repurposing and Optimizing,” for some technical suggestions on encoders and players, and Chapter 13, “Presenting Your Portfolio,” for how to disseminate and present it.

Creating multiple reels

As recently as 2005, you slaved over one perfect reel as your calling card, and sent it everywhere. That has begun to change. In the current marketplace, you can miss an opportunity just because your title screen and lead-off clip appear to put you in the wrong category for a freelance project. This is easily avoided by planning for the eventuality. We live in a world where the gods have given us non-linear editing tools, and it would be a pity to ignore the gift. Use your time in Adobe After Effects, or in Apple Final Cut Studio to build reel variations for the alternate job positions you can imagine yourself being qualified to fill.

Multiple versions still require advance work, and they are admittedly easier for a film/video person to develop than for an animator, whose clips need to segue seamlessly. But as you work on more projects, you may find that you have two or three stellar projects that display different aspects of your talent. If so, you can create two similar, but not identical, reels with different emphases.

WWW.HERCFERN.COM

At the very least, your reel breakdown should provide a title for the work, a legend or image to help people match the pieces up, and as exact a statement as possible of what part of the project was yours.

The other way to handle the challenge is to create and maintain a wrapper portfolio that clearly defines your different skills and allows the audience to download the reel, or view the section, that is relevant to them.

Wrapping the reel

Creating a wrapper for your reel is essentially the same thing as creating a regular disc or online portfolio, with your reel as the jewel at its center. The wrapper allows multitalented people the opportunity to show their ability to handle another visual medium, and is particularly useful for, say, a 3D animator or video pro who wants to be seen as the perfect jack-of-all-trades for a small animation studio or game developer. If you are not such a person, don’t wing it on the wrapper. Read the section on Partnering in Chapter 1, “Assessment and Adapation,” and find a graphic designer.

If you are planning on a DVD menu, be sure to create a structure with submenus, as covered in Chapter 10, “Designing a Portfolio Interface.” You’ll find that you have to consider many of the same issues for a DVD menu as you would encounter for a website, from grouping to a site map.

Either way, make sure you have a reel version that is small and fast enough to play on your website, and link it to a downloadable high-resolution version. Provide full-length versions of the best pieces in your reel if you own the rights to them, and if you do not, provide links to the studio that does own the rights.

Portfolio highlight: Metaversal Studios | Reel life

Portfolio development isn’t easy. Although great portfolios project a beautiful inevitability, you’re still conscious that there are calculated decisions behind them. In fact, in the design professions, part of the project is to make other designers and potential clients sufficiently aware of the site decisions that they want to claim that creativity for their own. Reels are different but equally exacting. Even those that are focused on technical prowess have to be perfect gems of entertainment.

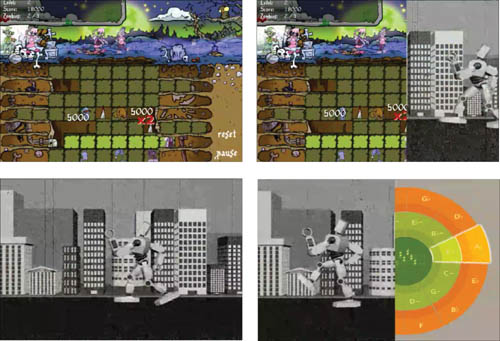

Now imagine putting both of these development challenges together, and add the requirement that both site and reel have to exude that elusive element: fun. That pretty much describes the requirements for a game developer’s site. There’s a lot of pressure to hit that mark, but Metaversal Studios seems comfortable batting cleanup. Their reel is a nonstop adventure with textbook-perfect pacing and variety.

Metaversal’s site navigation is simple and unobtrusive. Shallow dropdown menus make all major categories available, and a click on the Metaversal logo brings you back to the homepage. Always on this page are the demo reel and three game links, selected to showcase their newest, most popular, or most topical offerings.

Navigation and site content

Jay Laird, Metaversal’s lead game developer and founder, knows that people come to the site for two things. The nonprofit and corporate clients come to check out their reel, and avid casual gamers visit to play an online game. Their site meets the both demographics’ needs by putting these most important elements on the home page. The visual tension between the nerdy goofiness of their games and the cleanly corporate neatness of the interface is notable.

Their text plays the balancing game as well. Much of the site is devoted to detailed case studies for corporate clients, but it is extremely easy for the casual game player to avoid these sections completely. The areas that are likely to be read by both types of visitors are just a little tongue-in-cheek—toned down for the gamers, but a lightly entertaining break for the clientele.

A serious bio turns playful if you roll over the portrait photo. The new image reveals the true cartoon essence of each member of the Metaversal staff.

Game developer sites have to be very sticky. The idea is that, the longer you spend playing, exploring, and enjoying, the more likely it is that you will become a client or a dedicated user. A variety of content is key to making this happen. Metaversal is known for the range and diversity of their game topics and gameplay, and for their quality visuals. They combine traditional word games with wryly topical quizzes. Their special event games, from the Halloween ZombieDrop to the Thanksgiving game pitting turkeys against Pilgrims, are visually adept, fun to play, and display the kind of twisted humor that many game developers reach for but seldom grasp.

Reel structure and content

Metaversal’s demo reel is not very long, but it feels very rich and packed with content. The first images blast the message that the reel will take you on a fast-paced journey as you speed by planets and dance through musical clefs before being introduced to the first of many beautifully-conceived and rendered game animations.

One of many delightful time-wasters on the Metaversal site is T-Day, which sends turkeys back in time to try to prevent the Pilgrims from landing and bringing Thanksgiving Day into existence. The turkeys, being turkeys, neglect to bring any weapons, so you use a slingshot to throw them into the air toward their targets. You fight on the seas, fight in the air, fight on the ground, and turn into roasters if you fail. The inevitable result is made palatable by the smooth and responsive gameplay and the rich illustrations.

Hit a glowing boat and a power-up hits your plate. Something different happens to the Pilgrims for each special icon that is put in play. Select the snowflake icon, and winter descends, freezing all the Pilgrims in progress.

The segues between each clip in the demo reel are smooth, with a strong emphasis on transitions that connect the dominant motion of each clip to its predecessor. In the ZombieDrop game, the coffins shift left and right, so following that clip with a giant robot striding left feels natural.

To show the beautifully rendered detail of Metaversal’s characters, one clip elegantly steps through the technique of bringing a character and scene to life.

One game clip is tightly cut through time lapse to display several layers with a similar layout but brilliantly different graphics. Another walks through an educational interface game for learning the formal language of music. All impress with their visual range and diverse subject matter. They end, literally, with a bang, and a wag of the tail from a bomb-defusing dog created for an engineering project.

When you think about the reel afterwards, you realize that it does more than just show the reach and variety of Metaversal’s work as it bounces between different types of games and interfaces. Each individual clip has a different point to make about what they do and how. It’s a fun reel to watch the first time, and it brings a smile even on repetition as you pick up on more of their subversive humor.

Future plans

Laird and crew view their current website as a work in progress. The demo reel is updated when groups of major projects are completed, since it needs to be carefully rethought before adding anything new that would change the flow and tempo. Laird is extremely conscious of the Metaversal brand, and wants the site to continue to be seen by the typical gamer as slightly subversive while not alienating corporate clients. Changes are constant, but are mostly incremental. As Laird says, “Word of mouth has been our best source of business, and our website has proven to be the best calling card for our work.”