Chapter 7

Cascading Style Sheets

What You Will Learn in This Chapter

- What makes up a CSS rule

- How properties and values control the presentation of different elements within your document

- How to control the presentation of text using CSS

- How CSS is based on a box model, and how you set different properties for these boxes (such as width and styles of borders)

Wrox.com Code Downloads for this Chapter

The wrox.com code downloads for this chapter are found at www.wrox.com/remtitle.cgi?isbn=9781118340189 on the Download Code tab. The code is in the Chapter 7 download and individually named according to the names throughout the chapter.

Having learned how to structure the content of your documents using HTML’s wide variety of elements and attributes, you can now start making your pages look a lot more exciting.

In this chapter, you learn how to use cascading style sheets (CSS) to take control of the style of your pages, including the color and size of fonts, the width and color of lines, and the amount of space between items on the page. The cascading style sheets specification works by enabling you to specify rules that say how the content of elements within your document should appear. For example, you can specify that the background of the page is a cream color, the contents of all <p> elements should display in gray using the Arial typeface, and all <h1> elements should be in red using the Times New Roman typeface.

By the end of the chapter, you should be confidently writing CSS style sheets and should have learned many of the properties you can use to affect the presentation of any document using CSS.

Introducing CSS

CSS works by enabling you to associate rules with the elements that appear in a web page. These rules govern how the content of those elements should be rendered. Figure 7-1 shows an example of a CSS rule, which is made up of two parts:

- The selector indicates which element or elements the declaration applies to. (If it applies to more than one element, you can have a comma-separated list of several elements.)

- The declaration sets out how the elements referred to in the selector should be styled.

The rule in Figure 7-1 applies to all <td> elements and indicates that they should be 36 pixels wide.

The declaration is also split into two parts, separated by a colon:

- A property is the property of the selected element(s) that you want to affect, in this case the width property.

- A value is a specification for this property; in this case it is that table cells should be 36 pixels wide.

This is similar to the way that HTML elements can carry attributes and how the attribute controls a property of the element; the attributes’ value would be the setting for that property. For example, a <td> element could have a width attribute whose value is the width you want the table to be:

<td width="36"></td>With CSS, however, rather than specifying the attribute on each instance of the <td> element, the selector indicates that this one rule applies to all <td> elements in the document.

Here is an example of a CSS rule that applies to several different elements (the <h1>, <h2>, and <h3> elements). A comma separates the name of each element that this rule applies to. The rule also specifies several properties for these elements with each property-value pair separated by a semicolon. Note how all the properties are kept inside the curly braces:

h1, h2, h3 {

font-weight : bold;

font-family : arial;

color : #000000;

background-color : #FFFFFF;

}Even if you have never seen a CSS rule before, you should now have a good idea of what this rule does. There are three heading elements named in the selector (<h1>, <h2>, and <h3>), and this rule says that where these headings are used they will be written in a bold Arial font in black with a white background.

A Basic Example

Now look at an example that shows how a set of CSS rules can transform the look of an HTML page. CSS rules can live inside the HTML document. Although, this example makes a separate file to hold the CSS rules, and the HTML page contains a link to this file, which is known as a style sheet.

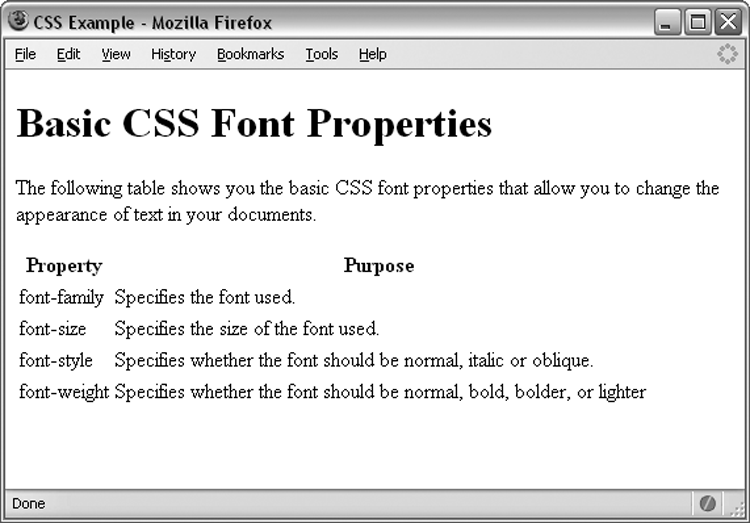

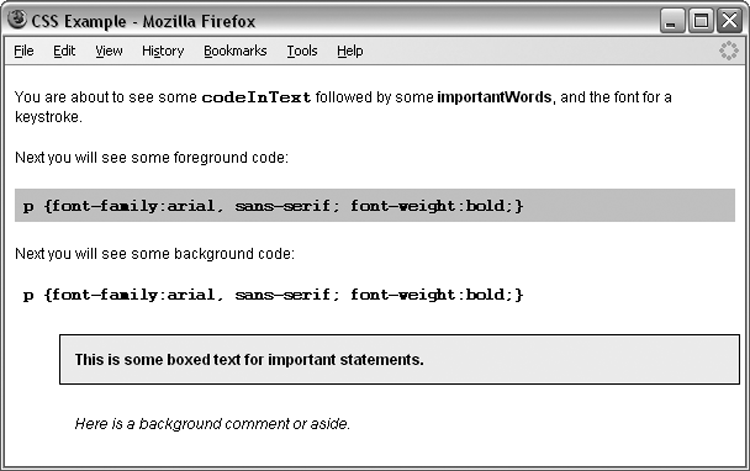

Before you meet the style sheet, look at Figure 7-2, which shows the HTML page you will be styling on its own before the CSS rules have been attached.

The code for the page you saw in Figure 7-2 (ch07_eg01.html) contains a heading, a paragraph, and a table. Inside the <head> element is a <link> element that tells the browser where to find the style sheet that will style this page; the location of the style sheet is given as the value of the href attribute. Also look at how some of the <td> elements carry a class attribute whose value is code. This distinguishes the table cells that contain code from other <td> elements in the document.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>CSS Example</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="ch07_eg01.css">

</head>

<body>

<h1>Basic CSS Font Properties</h1>

<p>The following table shows you the basic CSS font properties that allow

you to change the appearance of text in your documents.</p>

<table>

<tr>

<th>Property</th>

<th>Purpose</th>

</tr>

<tr>

<td class="code">font-family</td>

<td>Specifies the font used.</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td class="code">font-size</td>

<td>Specifies the size of the font used.</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td class="code">font-style</td>

<td>Specifies whether the font should be normal, italic or oblique.</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td class="code">font-weight</td>

<td>Specifies whether the font should be normal, bold, bolder, or lighter</td>

</tr>

</table>

</body>

</html>Now look at how to style this page. Figure 7-3 shows how the page looks with the style sheet attached.

You can create a style sheet in the same editor you use to create your HTML pages. After you create a CSS file, it is saved with the file extension .css.

The style sheet for this example (ch07_eg01.css) uses several CSS rules. Now go through them one at a time so that you can see what each one does.

Before the first rule, however, there is a comment to tell you which file this style sheet was written for. Anything between the opening /* and closing */ is ignored by the browser and therefore does not have an effect on the appearance of the page:

/* Style sheet for ch07_eg01.html */After the comment, the first rule applies to the <body> element. It specifies that the default color of any text and lines used on the page will be black and that the background of the page should be white. The colors here are represented using a hex code. (Appendix D, “Color Names and Values,” covers the different ways to specify colors.) It also states that the typeface used throughout the document should be Arial. If Arial is not available, Verdana will be used instead; failing that, it will use its default font group that corresponds to that generic font group.

body {

color:#000000;

background-color : #ffffff;

font-family : arial, verdana, sans-serif;

}The next two rules simply specify the size of the contents of the <h1> and <p> elements, respectively. (As you will see in the section “Lengths,” px stands for pixels.)

h1 {

font-size : 18px;

}

p {

font-size : 12px;

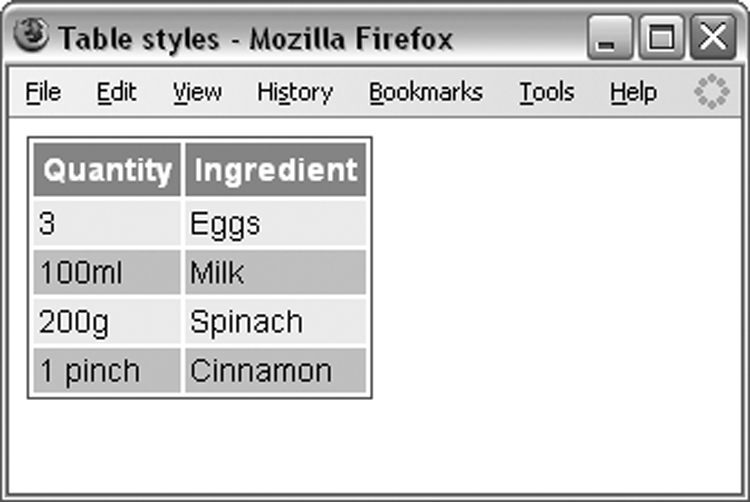

}Next, it is time to add a few settings to control the appearance of the table. First, give it a light gray background. Then, draw a border around the edge. Three properties are used to describe the border: The first says it is a solid line (rather than a dashed or dotted line), the second says it should be 1 pixel thick, and the third specifies that it should be light gray:

table {

background-color : #efefef;

border-style : solid;

border-width : 1px;

border-color : #999999;

}Within the table, the table headings should have a medium gray background color (slightly darker than the main body of the table); the text should appear in a bold font; and between the edge of the cell and the text, there should be 5 pixels of padding. (As you will see in more detail in the section “The padding Property,” padding is the term used for the space between the edge of a box and the content inside it.)

th {

background-color : #cccccc;

font-weight : bold;

padding : 5px;

}The individual table data cells also have 5 pixels of padding (like the headings). Adding this space makes the text much easier to read, and without it the text in one column might run up right next to the text in the neighboring column:

td {

padding : 5px;

}Finally, you may have noticed in Figure 7-3 that the cells of the table that contained the names of CSS properties were in a Courier font. If you look at the corresponding table cells in the HTML document, they carried a class attribute whose value was code. On its own, the class attribute does not change the display of the document (refer to Figure 7-2), but the class attribute does enable you to associate CSS rules with elements whose class attribute has a specific value. Therefore, the following rule applies only to <td> elements that carry a class attribute whose value is code, not to all <td> elements:

td.code {

font-family : courier, courier-new, serif;

font-weight : bold;

}When you want to specify an element whose class attribute has a specific value, you put the value of that class attribute preceded by a period (or full stop) symbol.

There you have the first example; you can find the code for this example (ch07_eg01.html) with the download code for the rest of the book. This example provides you with an overview of how CSS works. Therefore, for the rest of this chapter and the following chapter you need to look at

- The properties you can use to control the appearance of various elements, and the values they can take. The different properties are grouped throughout this chapter and the next. For example, the properties that affect the appearance of fonts are together, those that affect borders are together, and so on.

- Different selectors that enable you to specify which elements these properties apply to. The basic example featured just a few of the many methods you can use to indicate which elements are controlled by which style rules.

- How CSS treats each element in a web page as if it were in its own box and how this affects the way in which you lay out web pages.

Along the way you also see where you can use CSS rules in your documents, the units of measurements used in CSS (such as pixels and percentages), and a powerful concept called inheritance.

Inheritance

One of the powerful features of CSS is that when a property has been applied to one element, it will often be inherited by child elements (elements contained within the element that the rules were declared upon). For example, after the font-family property had been declared for the <body> element in the previous example, it applied to all the elements inside the <body> element. This saves you from repeating the same rules for every element that makes up a web page.

If another rule is more specific about which elements it applies to, then it overrides any properties associated with the <body> element or any other containing element. In the preceding example, most of the text was in an Arial typeface, as specified in the rule associated with the <body> element; although, there were a few table cells that used a Courier typeface. The table cells that were different had a class attribute whose value was code:

<td class="code">font-size</td>Here you can see the rule associated with these elements:

td.code {

font-family : courier, courier-new, serif;

font-weight : bold;

}This rule takes precedence over the one associated with the <body> element because the selector is more specific about which element it applies to. The W3C site (http://www.w3.org/TR/CSS21/cascade.html#specificity) offers a set of rules for determining how specific a rule is. Warning, it’s not for the faint of heart.

The way in which some properties inherit saves you from writing out rules and all the property-value pairs for each element and makes for a more compact style sheet. Appendix C, “CSS Properties,” is a handy reference and tells you which ones do and do not inherit.

Where You Can Add CSS Rules

The example that you saw at the beginning of the chapter placed the CSS rules in a separate file known as an external style sheet. CSS rules can also appear in two places inside the HTML document:

- Inside a <style> element, which sits inside the <head> element of a document

- As a value of a style attribute on any element that can carry the style attribute

When the style sheet rules are held inside a <style> element in the head of the document, they are referred to as an internal style sheet.

<head>

<title>Internal Style sheet</title>

<style type="text/css">

body {

color : #000000;

background-color : #ffffff;

font-family : arial, verdana, sans-serif;

}

h1 {

font-size : 18pt;

}

p {

font-size : 12pt;

}

</style>

</head>When style attributes are used on HTML elements, they are known as inline style rules, for example:

<td style="font-family:courier; padding:5px; border-style:solid;

border-width:1px; border-color:#000000; ">Here you can see that the properties are added as the value of the style attribute. You still need to separate each property from its value with a colon and each of the property-value pairs from each other with a semicolon. However, there is no need for a selector here (because the style is automatically applied to the element that carries the style attribute), and there are no curly braces.

You should generally avoid using both inline style rules and internal style sheets in favor of using external style sheets. There are some cases in which both are useful, but external sheets are much easier to maintain. You learn more about this in the “Advantages of External Style Sheets” section.

As you’ve already learned, external style sheets are loaded using the <link> element. Before moving on, take a slightly more in-depth look at the <link> element and associated attributes.

The <link> Element

The <link> element is used in web pages to describe the relationship between two documents; for example, it can be used in an HTML page to specify a style sheet that should be used to style a page. You may also see the <link> element used in HTML pages for other purposes, for example, to specify an RSS feed that corresponds with a page.

It is a different kind of link than the <a> element because the two documents are automatically associated—the user does not need to click anything to activate the link.

The <link> element is always an empty element, and when used with style sheets, it must carry two attributes: rel and href. Here is an example of the <link> element used in an HTML page indicating that it should be styled by a CSS file called interface.css, which lives in a subdirectory called CSS:

<link rel="stylesheet" href="../CSS/interface.css">In addition to the core attributes, the <link> element can also take the following attributes:

charset href hreflang media rel type sizes targetYou have met many of these already, so the more important ones are discussed in the following sections.

The rel Attribute

The rel attribute is required and specifies the relationship between the document containing the link and the document being linked to. The key value for working with style sheets is stylesheet:

rel="stylesheet"The other possible values for this element are discussed in Chapter 3, “Links and Navigation.”

The href Attribute

The href attribute specifies the URL for the document being linked to:

href="../stylesheets/interface.css"The value of this attribute can be an absolute or relative URL (which were covered in Chapter 3, “Links and Navigation”), but it is usually a relative URL because the style sheet is part of the site.

The media Attribute

The media attribute specifies the output device that is intended for use with the document:

media="screen"Although this attribute is not always used, it is important because people access the Internet in different ways using different devices. Table 7-1 shows the possible values.

Table 7-1: Values of the media Attribute

| Value | Uses |

| screen | Nonpaged computer screens (such as desktop computers and laptops) |

| tty | Media with a fixed-pitch character grid, such as teletypes, terminals, or portable devices with limited display capabilities |

| Tv | TV devices with low-resolution, color screens, and limited ability to scroll down pages |

| Printed documents, which are sometimes referred to as paged media (and documents shown onscreen in print preview mode) | |

| projection | Projectors |

| handheld | Handheld devices, which often have small screens, rely upon bitmapped graphics, and have limited bandwidth |

| braille | Braille tactile feedback devices |

| embossed | Braille paged printers |

| speech | Speech synthesizers |

| all | Suitable for all devices |

The <style> Element

The <style> element is used inside the <head> element to contain style sheet rules within a web page, rather than linking to an external document. It is also sometimes used when a single page needs to contain just a few extra rules that do not apply to the other pages of the site that all share the same style sheet.

For example, here is a style sheet attached to the HTML document using the <link> element you just learned about, as well as a <style> element containing an additional rule for <h1> elements:

<head>

<title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="../styles/mySite.css">

<style type="text/css">

h1 {

color:#Fc00f000;

}

</style>

</head>When you use the <style> element it should always carry the type attribute although it’s not mandatory. In addition to all the global attributes, it can carry:

type media scopedAdvantages of External Style Sheets

If two or more documents are going to use a style sheet, you should use an external style sheet. There are several reasons for this, including the following:

- It saves you repeating the same style rules in each page.

- You can change the appearance of several pages by altering just the style sheet rather than each individual page. This means it is easier to update your site if you want to, for example, change the style of font used in all headings or alter the color of all links.

- After a visitor to your site has downloaded the CSS with the first page of your site that uses it, subsequent pages will be quicker to load (because the browser retains a copy of the style sheet and the rules do not need to be downloaded for every page). This also puts less strain on the server (the computer that sends the web pages to the people viewing the site) because the pages it sends out are smaller.

- The style sheet can act as a style template to help different authors achieve the same style of document without learning all the individual style settings.

- Because the web pages do not contain the style rules, different style sheets can be attached to the same document. So you can use the same HTML document with one style sheet when the viewer is on a desktop computer, another style sheet when the user has a handheld device, another style sheet when the page is being printed, another style sheet when the page is being viewed on a TV, and so on. You can reuse the same document with different style sheets for different visitors’ needs.

- A style sheet can import and use styles from other style sheets, allowing for modular development and good reuse.

- If you remove the style sheet, you can make the site more accessible for those with visual impairments because you are no longer controlling the fonts and color schemes.

It is fair to say, therefore, that whenever you write a whole site, you should use an external style sheet to control the presentation of it (rather than putting CSS rules in the individual web pages). Although, as you see in the next chapter, you might use several external style sheets for different aspects of the site.

CSS Properties

You now know that styling a web page using CSS involves creating rules, and these rules contain two parts: a selector to indicate which elements the rule applies to and one or more properties that control the presentation of these elements. So, if there is a part of the page that you want to make a certain color or size, then you need to use the correct selector to target that part of the page and the correct properties to change their appearance accordingly.

The properties are grouped together into related functionality; for example, there are properties that enable you to control the presentation of tables, lists, and backgrounds. The following list shows the main properties available to you, all of which you meet in this chapter or Chapter 8, “More Cascading Style Sheets.”

FONT

TEXT

BACKGROUND

BORDER

MARGIN

PADDING

DIMENSIONS

POSITIONING

OUTLINES

TABLE

LIST and MARKER

GENERATED CONTENT

CLASSIFICATION

In addition there is a new version of CSS, CSS3, which focuses on modules. These modules are broken into separate areas of focus. The following modules are the focus of Chapter 9, “Rounded Corners, Animations, Custom Fonts, and More with CSS3”:

- Selectors

- Color

- Backgrounds and Borders

- Multicolumn Layout

- Media Queries

- Fonts

- 2D Transforms

- 3D Transforms

- Animations and Transitions

There are also some properties that are not covered in this book, either because they are rarely used or because there is little support for them. (For example, aural style sheets because there are not many aural browsers that support them.) You can find out more about these properties on the following websites, or you can read a book dedicated to CSS:

Controlling Text

Several properties enable you to control the appearance of text in your documents. These can be split into two groups:

- Those that directly affect the font and its appearance. (These include the typeface used, whether it is regular, bold, or italic, and the size of the text.)

- Those that would have the same effect on the text irrespective of the font used. (These include the color of the text and the spacing between words or letters.)

Table 7-2 lists the properties that directly affect the font (the first of these two groups):

Table 7-2: Font Properties

| Property | Purpose |

| font | Enables you to combine several of the following properties into one. |

| font-family | Specifies the typeface or family of the font that should be used. |

| font-size | Specifies the size of the font. |

| font-weight | Specifies whether the font should be normal or bold. |

| font-style | Specifies whether the font should be normal, italic, or oblique. |

| font-variant | Specifies whether the font should be normal or small caps. |

Before looking at these properties in detail, it helps to understand some key terms used in typography. Perhaps most important, a font is not the same thing as a typeface:

- A typeface is a family of fonts, such as the Arial family.

- A font is a specific member of that family, such as Arial 12-point bold.

You often see the terms used interchangeably, but it is helpful to be aware of the distinction.

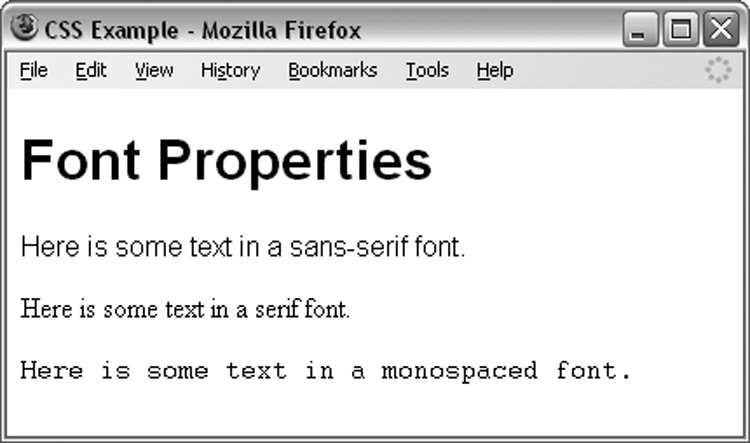

Typefaces tend to belong to one of two groups: serif and sans-serif fonts. Serif fonts have extra curls on letters. For example, in Figure 7-4, the first l contains a serif on the top of the letter and at the bottom of the letter, whereas sans-serif fonts have straight ends to the letters, such as in the second example. The third common style of a typeface is a monospaced serif font. Every letter in a monospaced font is the same width, whereas nonmonospaced fonts have different widths for different letters. (For example, in serif and sans-serif fonts, the l tends to be narrower than the m.)

Serif fonts are generally assumed to be easier to read for large amounts of printed text. But on the Internet many people find serif fonts harder to read for long stretches, largely because the resolution of a computer screen is not as good as printed documents, which makes the less detailed sans-serif fonts easier to read.

So that you can study the properties that affect fonts, most of the examples in the following section use a similar structure. Paragraphs of text will be repeated, and each <p> element carries a class attribute with a different value, for example:

<p class="sans-serif">Here is some text in a sans-serif font.</p>

<p class="serif">Here is some text in a serif font.</p>

<p class="monospace">Here is some text in a monospaced font.</p>You can then see how different properties affect each <p> element by writing a separate rule for each paragraph. You can use the value of the class attributes in the CSS selectors to create rules that apply just to one <p> element at a time.

The font-family Property

The font-family property enables you to specify the typeface that should be used for any text inside the element(s) that a CSS rule applies to.

When choosing typefaces you must know that without using the @font-face directive, covered in Chapter 9, browsers can display only HTML text in the font you have specified if that typeface is installed on that computer. So, if you specify a font such as Futura or Garamond, and I do not have it on my computer, I would see the text in a different font—not the one you specified.

This is why, if you look at a selection of websites, most rely heavily on a small selection of typefaces installed on most computers that access the web, in particular Arial, Courier/Courier New, Georgia, Times/Times New Roman, and Verdana. (From this list, Arial and Verdana are particularly popular because they are considered easy to read online.)

To help matters, you can specify a list of typefaces so that if users do not have your first choice of typeface installed on their computer, the browser can try to show the text in your second or third choice. Each typeface in the list is separated by a comma, and if the name contains spaces (such as times new roman or courier new) you should place the name of the typeface in double quotation marks (ch07_eg02.css), like so:

p.sans-serif {

font-family : arial, verdana, sans-serif;

}

p.serif {

font-family : times, "times new roman", serif;

}

p.monospace {

font-family : courier, "courier new", monospace;

}Figure 7-5 shows what this example would look like in a browser; you can see the different types of fonts used for each paragraph (ch07_eg02.html).

You may notice that each list of typefaces in the previous example ends with so-called generic font names (sans-serif, serif, and monospace). The idea behind these is that each computer will have a font that corresponds to one of five generic font groups (sans-serif, serif, monospace, cursive, and fantasy), and if it cannot find the typefaces you have specified, it can use its choice of font that corresponds to that generic font group, as shown in Table 7-3.

Table 7-3: Generic Font Names

| Generic Font Name | Type of Font | Example |

| serif | Fonts with serifs | Times |

| sans-serif | Fonts without serifs |

file://.../image_fi/340189c07/c07uf001.eps

|

| monospace | Fixed-width fonts | Courier |

| cursive | Fonts that emulate handwriting |

file://.../image_fi/340189c07/c07uf002.eps

|

| fantasy | Decorative fonts for titles and so on | Impact |

One thing to consider when choosing a list of fonts is that each font can be of different heights or widths, so you probably want to choose a list of fonts that are of a similar size. (Otherwise, the layout could look different to what you expect.) For example, Courier New is quite short and wide, so if this were your first choice, it would not be good to have Impact as a second choice because Impact is quite tall and narrow.

If you want to use a specific typeface, you must wade into the slightly scary waters of web fonts. Chapter 9 covers the benefits and shortcomings of this new technology.

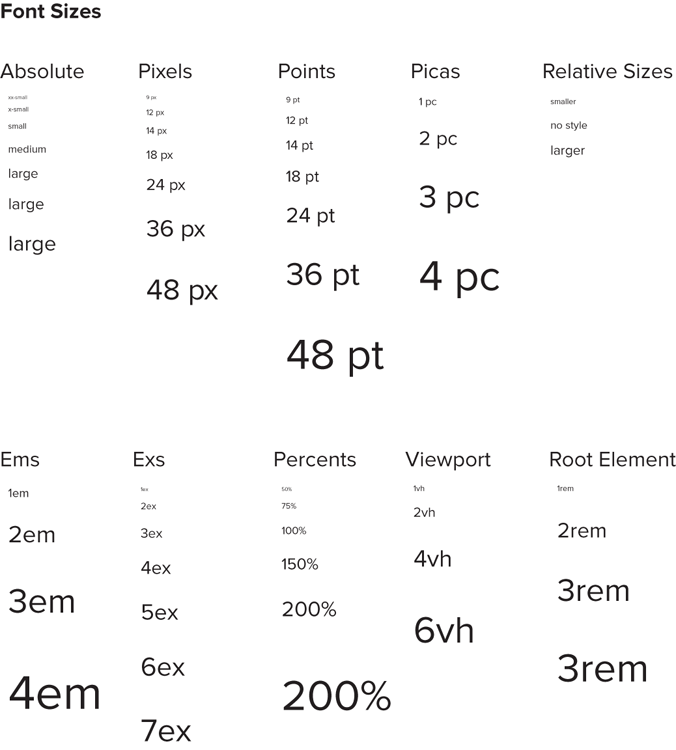

The font-size Property

The font-size property enables you to specify a size for the font. You often see the value for this property specified in pixels, like so:

p.twelve {

font-size : 12px;

}However, you can provide a value in many ways:

- Length: (Along with pixels, there are several other units of length that you will learn about in the section “Lengths” later in this chapter.)

px em ex pt in cm pc mm rem vw vh

- Absolute size: Each of these values corresponds to a fixed size:

xx-small x-small small medium large x-large xx-large

- Relative size: This value is relative to the surrounding text:

smaller larger

- Percentage: A percentage is calculated as a proportion of the parent element:

2% 10% 25% 50% 100%

Here is an example of each of these ways to specify a value for the font-size property:

p.one {

font-size : xx-small;

}

p.twelve {

font-size : 12px;

}

p.thirteen {

font-size : 3pc;

}

p.fourteen {

font-size : 10%;

}Figure 7-6 shows how a selection of these font sizes works in the browser. (ch07_eg03.html and ch07_eg03.css contain several examples of different ways to specify size and compare how they look.)

The font-weight Property

Most fonts have different variations, such as bold and italic. When typographers create a new font, it is not unusual for them to individually craft a separate, thicker version of each character for the bold variation.

Despite all this careful work, rather than finding the bold version of a typeface, browsers tend to use an algorithm that takes the normal version of the font and makes it thicker. Because it uses an algorithm, it means you can also create a lighter version of fonts. This is what the font-weight property is for.

The possible values for font-weight are:

normal bold bolder lighter 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900The following example uses several of these values (ch07_eg04.css):

p.one {

font-weight : normal;

}

p.two {

font-weight : bold;

}

p.three {

font-weight : normal;

}

p.three span {

font-weight : bolder;

}

p.four {

font-weight : bold;

}

p.four span {

font-weight : lighter;

}

p.five {

font-weight : 100;

}

p.six {

font-weight : 200;

}Figure 7-7 shows you how these values appear in the browser (ch07_eg04.html).

Of these values, bold is most commonly used. Although, you might see the use of normal. (Especially if a large section of text is already bold and an exception must be created in which just a few words are not in bold.)

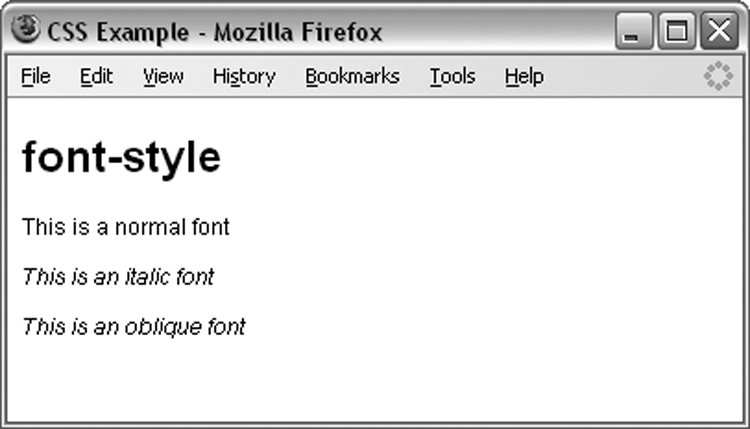

The font-style Property

The font-style property enables you to specify that a font should be normal, italic, or oblique, and these are the values of the font-style property, for example (ch07_eg05.css):

p.one {

font-style : normal;

}

p.two {

font-style : italic;

}

p.three {

font-style : oblique;

}Figure 7-8 shows you how these values appear in the browser (from ch07_eg05.html).

In typography, an italic version of a font would normally be a specifically stylized version of the font based on calligraphy, whereas an oblique version of the font would take the normal version of the font and place it at an angle. In CSS, when you specify a font-style property should be italic, browsers usually take the normal version of the font and simply render it at an angle (as you would expect with an oblique version of a font).

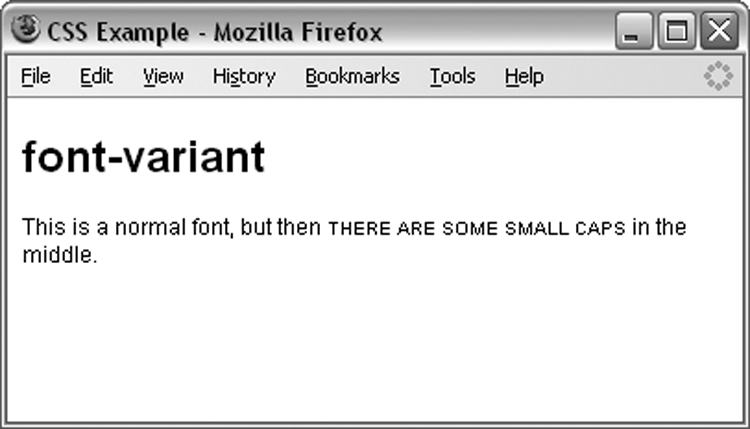

The font-variant Property

There are two possible values for the font-variant property: normal and small-caps. A small caps font looks like a smaller version of the uppercase letterset.

For example, look at the following paragraph, which contains a <span> with a class attribute (ch07_eg06.html):

<p>This is a normal font, but then <span class="smallcaps">there

are some small caps</span> in the middle.</p>Now look at the style sheet (ch07_eg06.css):

p {

font-variant : normal;

}

span.smallcaps {

font-variant : small-caps;

}As you can see from Figure 7-9, the rule associated with the <span> element indicates that its content should be shown in small caps.

Text Formatting

In addition to the properties that affect the font, several properties affect the appearance or formatting of your text (independently from the font it is shown in), as shown in Table 7-4.

Table 7-4: Text Formatting Properties

| Property | Purpose |

| color | Specifies the color of the text. |

| text-align | Specifies the horizontal alignment of the text within its containing element. |

| vertical-align | Specifies the vertical alignment of text within its containing element. |

| text-decoration | Specifies whether the text should be underlined, overlined, or strikethrough. |

| text-indent | Specifies an indent from the left border for the text. |

| text-transform | Specifies that the content of the element should all be uppercase, lowercase, or capitalized. |

| text-shadow | Specifies that the text should have a drop shadow. |

| letter-spacing | Controls the width between letters (known to print designers as tracking). |

| word-spacing | Controls the amount of space between each word. |

| white-space | Specifies whether the white space should be collapsed, preserved, or prevented from wrapping. |

| direction | Specifies the direction of text (similar to the dir attribute). |

The color Property

The color property enables you to specify the color of the text. The value of this property is most commonly a hex code for a color or a color name. (Both Chapter 9 and Appendix D further discuss the way in which colors are specified for the web.)

For example, the following rule (ch07_eg07.css) would make the content of paragraph elements red, as shown in ch07_eg07.html:

p {

color : #fc00f000;

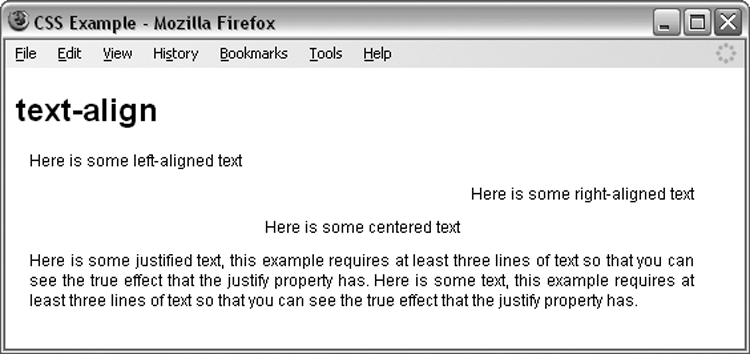

}The text-align Property

The text-align property works like the deprecated align attribute would with text. It aligns the text within its containing element or the browser window. Table 7-5 displays possible values.

Table 7-5: Possible Values for the text-align Property

| Value | Purpose |

| left | Aligns the text with the left border of the containing element. |

| right | Aligns the text with the right border of the containing element. |

| center | Centers the content in the middle of the containing element. |

| justify | Spreads the width across the whole width of the containing element. |

| start | Added in CSS3, aligns inline contents to the start of the line box. |

| end | Added in CSS3, aligns inline contents to the end of the line box. |

Figure 7-10 shows you how these would work in a table that is 500 pixels wide.

Here are the rules for each row of this example (ch07_eg08.css):

.leftAlign {

text-align : left;

}

.rightAlign {

text-align : right;

}

.center {

text-align : center;

}

.justify {

text-align : justify;

}The effects of these rules are shown in ch07_08.html.

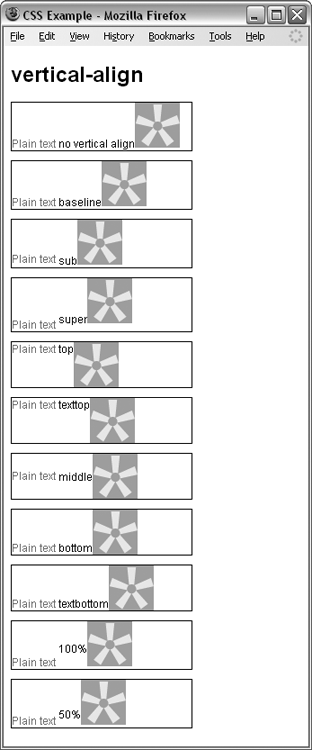

The vertical-align Property

The vertical-align property is useful when working with inline elements, in particular images and portions of text. It enables you to control their vertical positioning within the containing element, for example:

span.footnote {

vertical-align : sub;

}It can take several values, as shown in Table 7-6.

Table 7-6: Values for the vertical-align Property

| Value | Purpose |

| baseline | Aligns to the baseline of the parent element. (This is the default setting.) |

| sub | Makes the element subscript. With images, the top of the image should be on the baseline. With text, the top of the font body should be on the baseline. |

| super | Makes the element superscript. With images, the bottom of the image should be level with the top of the font. With text, the bottom of the descender (the parts of letters such as g and p that go beneath the line of text) should align with the top of the font body. |

| top | Aligns the top of the text and the top of the image with the top of the tallest element on the line. |

| text-top | Aligns the top of the text and the top of the image with the top of the tallest text on the line. |

| middle | Aligns the vertical midpoint of the element with the vertical midpoint of the parent. |

| bottom | Aligns the bottom of the text and the bottom of the image with the bottom of the lowest element on the line. |

| text-bottom | Aligns the bottom of the text and the bottom of the image with the bottom of the lowest text on the line. |

This property may also accept inherit, a length and a percentage value.

You can try out all these in your browser using ch07_eg09.html.

Figure 7-11 shows some of these values.

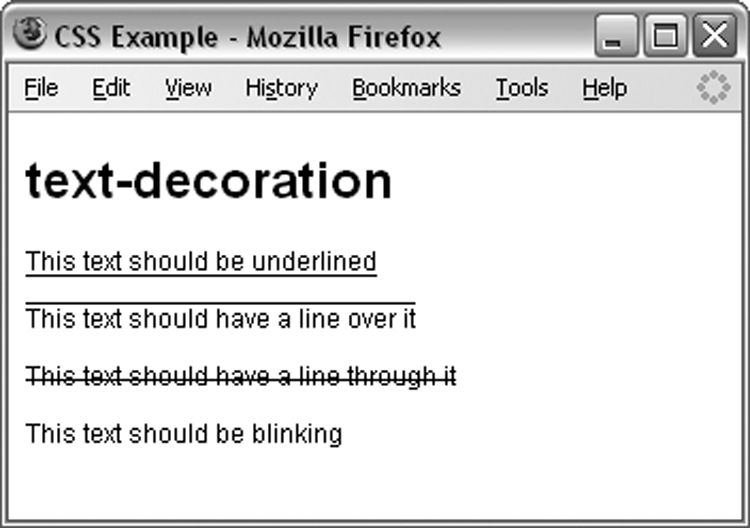

The text-decoration Property

The text-decoration property enables you to specify the values, as shown in Table 7-7.

Table 7-7: Values for the text-decoration Property

| Value | Purpose |

| underline | Adds a line under the content. |

| overline | Adds a line over the top of the content. |

| line-through | Adds a line through the middle of the content, such as strikethrough text. In general, this should be used only to indicate text marked for deletion. |

| none | Removes any text-decoration on an element. |

Here are these properties used on separate paragraphs (ch07_eg10.css):

p.underline {

text-decoration : underline;

}

p.overline {

text-decoration : overline;

}

p.line-through {

text-decoration : line-through;

}Figure 7-12 shows you what they look like in Firefox (ch07_eg10.html).

The text-indent Property

The text-indent property enables you to indent the first line of text within an element. In the following example it has been applied to the second paragraph (ch07_eg11.html):

<p>This paragraph should be aligned with the left-hand side of the browser. </p>

<p class="indent">Just the first line of this paragraph should be indented by

3 em, this should not apply to any subsequent lines in the same paragraph. </p>Now, here is the rule that indents the second paragraph (ch07_eg11.css):

.indent {

text-indent : 3em;

}You can see what this looks like in Figure 7-13.

The text-shadow Property

The text-shadow property is supposed to create a drop shadow, which is a dark version of the word just behind it and slightly offset. This has often been used in print media, and its popularity has meant that is has gained its own CSS property. The value for this property is quite complicated because it can take a color followed by three lengths (ch07_eg12.css):

.dropShadow {

text-shadow : #999999 10px 10px 3px;

}After the color has been specified, the first two lengths specify how far from the original text the drop shadow should fall (using X and Y coordinates), whereas the third specifies how blurred the drop shadow should be.

This property is supported in all the major browsers, including Internet Explorer 10 or later. Figure 7-14 shows what this example (ch07_eg12.html) looks like in Safari on a Mac.

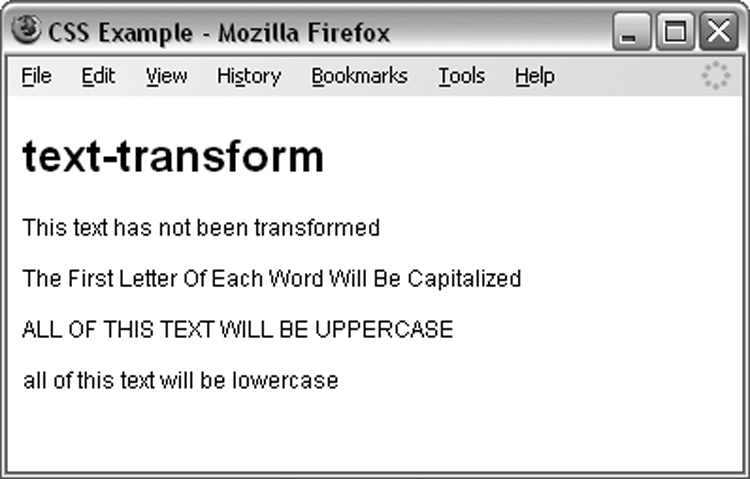

The text-transform Property

The text-transform property enables you to specify the case for the content of an element. The possible values are shown in Table 7-8.

Table 7-8: Values for the text-transform Property

| Value | Purpose |

| none | No change takes place. |

| capitalize | Capitalizes the first letter of every word. |

| uppercase | Makes the entire content of the element uppercase. |

| lowercase | Makes the entire content of the element lowercase. |

To demonstrate this property, in the following example there are four paragraphs (ch07_eg13.html):

<p class="none">This text has not been transformed</p>

<p class="capitalize">The first letter of each word will be capitalized</p>

<p class="uppercase">All of this text will be uppercase</p>

<p class="lowercase">ALL OF THIS TEXT WILL BE LOWERCASE</p>Here you can see the four different values for the text-transform property in use (ch07_eg13.css):

p.none {

text-transform : none;

}

p.capitalize {

text-transform : capitalize;

}

p.uppercase {

text-transform : uppercase;

}

p.lowercase {

text-transform : lowercase;

}Figure 7-15 shows you how the paragraphs would appear in a browser with these styles applied.

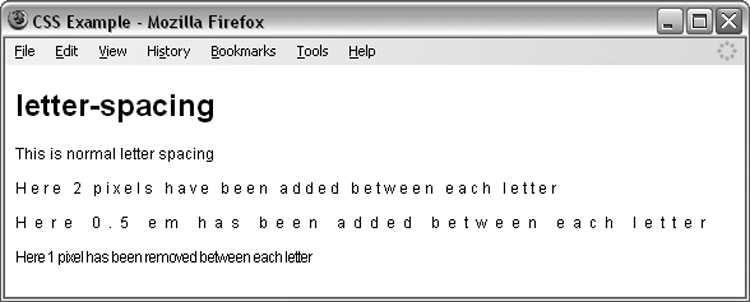

The letter-spacing Property

The letter-spacing property controls something that print designers refer to as tracking: the gap between letters. Loose tracking indicates that there is a lot of space between letters, whereas tight tracking refers to letters squeezed together. No tracking refers to the normal gap between letters for that font.

If you want to increase or decrease the spacing between letters, you most likely specify this in pixels or something known as an em. (Although, it can be any unit of length that CSS supports—you look at the CSS units of length in the “Length” section in this chapter.)

If you have a section of text where letter spacing has been altered, you can specify that an element should have no tracking using the keyword normal.

The first paragraph of the following example shows normal tracking. The second paragraph shows a gap of 3 pixels used between each letter. The third paragraph shows a gap between each letter of 0.5 em. The final paragraph shows spacing cut by 1 pixel from what it would have been in normal tracking (ch07_eg14.css):

.two {

letter-spacing : 3px;

}

.three {

letter-spacing : 0.5em;

}

.four {

letter-spacing : -1px;

}Figure 7-16 gives you an indication of what this looks like in a browser (ch07_eg14.html).

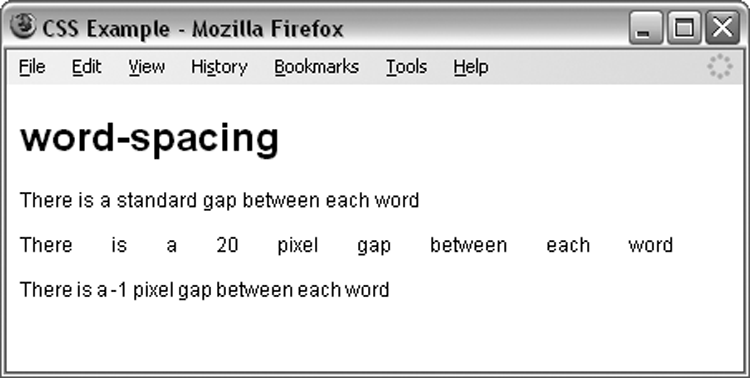

The word-spacing Property

The word-spacing property sets the gap between words, and its value should be a unit of length. In the following example (ch07_eg15.css), in the first paragraph there is a standard gap between each of the words. In the second paragraph the gap is 10 pixels between each of the words. In the final paragraph the gap has been cut to 1 pixel less than normal spacing:

.two {

word-spacing : 20px;

}

.three {

word-spacing : -1px;

}Figure 7-17 gives you an indication of what this looks like (ch07_eg15.html).

The white-space Property

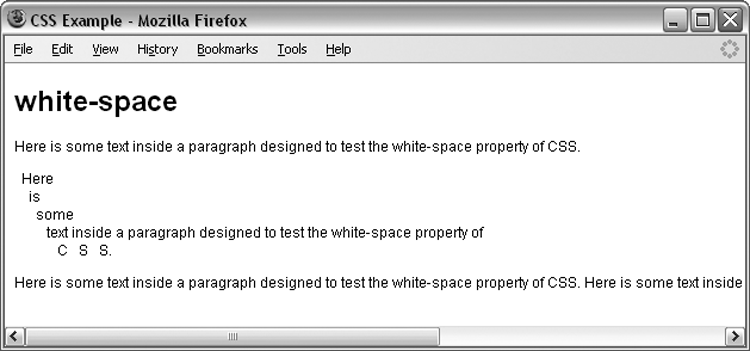

As you saw in Chapter 1, browsers change any two or more spaces next to each other into a single space and make any carriage returns a single space. The white-space property controls whether white space is preserved, offering the same results as the HTML <pre> element where white space is preserved and the nowrap attribute where text is broken only onto a new line if explicitly told to. Table 7-9 shows the possible values for this property.

Table 7-9: Values for the white-space Property

| Value | Purpose |

| normal | Follows normal white space collapsing rules. |

| pre | Preserves white space just as in the <pre> element of HTML, but the formatting is whatever is indicated for that element. (It is not a monospaced font by default like the <pre> element.) |

| nowrap | Breaks text onto a new line only if explicitly told to with a <br> element; otherwise text does not wrap. |

For example, you can use the white-space property like so (ch07_eg16.css):

.pre {

white-space : pre;

}

.nowrap {

white-space : nowrap;

}You can see both of these properties working in Figure 7-18 (ch07_eg16.html).

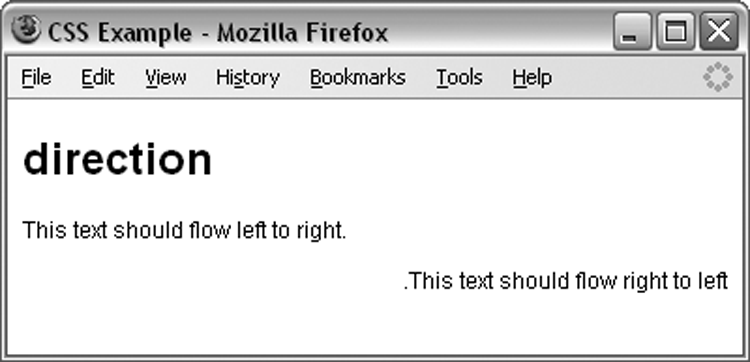

The direction Property

The direction property is rather like the dir attribute and specifies the direction in which the text should flow. Table 7-10 shows the possible values.

Table 7-10: Values for the direction Property

| Value | Purpose |

| ltr | The text flows from left to right. |

| rtl | The text flows from right to left. |

| inherit | The text flows in the same direction as its parent element. |

For example, here are rules for two paragraphs indicating different directions for the text (ch07_eg17.css used with ch07_eg17.html):

p.ltr {

direction : ltr;

}

p.rtl {

direction : rtl;

}In practice, both IE and Firefox use this property much as the align attribute is used. The value rtl simply right-aligns text, as shown in Figure 7-19. Note, however, that the period (or full stop) is to the left of the sentence in the paragraph that is supposed to be running right to left.

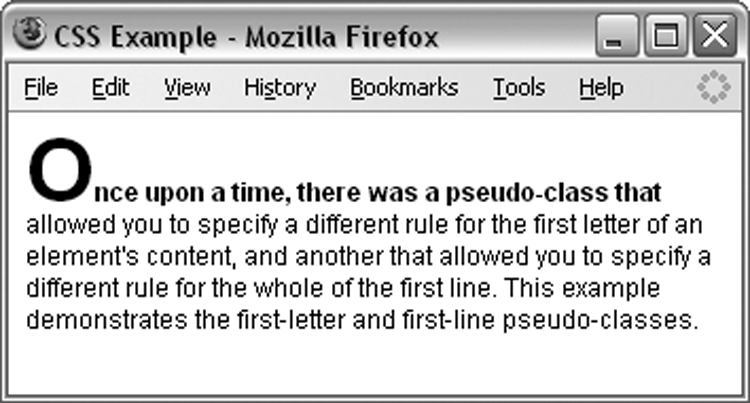

Text Pseudo-Classes

While you are learning about text, there are two pseudo-classes that can help you work with text. These pseudo-classes enable you to render either the first letter or the first line of an element in a different way than the rest of that element.

The first-letter Pseudo-Class

The first-letter pseudo-class enables you to specify a rule just for the first letter of an element. This is most commonly used on the first character of a new page, either in some magazine articles or in books.

Here is an example of the first-letter pseudo-class applied to a <p> element that has a class attribute whose value is introduction. Note how the selector for the element and the first-letter pseudo-class are separated by a colon (ch07_eg18.css used with ch07_eg18.html):

p.introduction:first-letter {

font-size : 42px;

}Figure 7-20 shows the effect of this first-letter pseudo-class (and also shows the next pseudo-class you look at).

The first-line Pseudo-Class

The first-line pseudo-class enables you to render the first line of any paragraph differently from the rest of the paragraph. Commonly, this is a bold font so that the reader can clearly see an introduction (for articles) or the first line (for poems).

The name of the pseudo-class is separated from the selector for the element by a colon:

p.introduction:first-line {

font-weight : bold;

}It is worth trying this example out in a browser because if you resize the window so that there is less text on the first line, you can see how only the first line of text in the browser is given this new style. Refer to Figure 7-20 to see the first-line pseudo-class in action, which also demonstrates the first-letter pseudo-class.

Styling Text

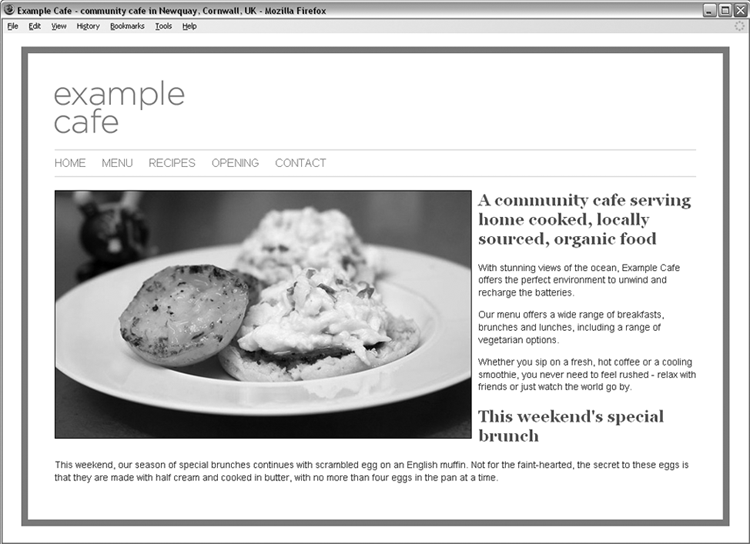

The single most common task with CSS on the web is styling text. In this next Try It Out, you style text on the sample website.

/* style sheet for Example Cafe */body {

font-family : arial, verdana, sans-serif;

}h2 {

font-family : georgia, times, serif;

color : #666666;

}p {

font-size:90%;

color:#333333;

} <nav id="navigation">

HOME

<a href="menu.html">MENU</a>

<a href="recipes.html">RECIPES</a>

<a href="opening.html">OPENING</a>

<a href="contact.html">CONTACT</a>

</nav>#navigation a {

color:#3399cc;

}#navigation a {

color : #3399cc;

text-decoration : none;

}<link rel="stylesheet" href="css/interface.css">Selectors

So far, you have seen lots of examples of properties that affect the presentation of text, and you have seen how you can apply these properties to elements using style rules. Before continuing to look at more properties, you need to look at some more fundamental issues. Start by looking at how you can use a different type of a selector to specify which elements a style sheet rule can apply to. There are actually several ways to do this, not just by using the names of the elements as you have seen so far in this chapter (which is, incidentally, known as a simple selector) or using the value of the class attribute or id attribute. Learn how in the next few sections.

Universal Selector

The universal selector is an asterisk; it is like a wildcard and matches all element types in the document.

*{}If you want a rule to apply to all elements, you can use this selector. Sometimes it is used for default values that apply to the whole of the document (such as a font-family and font-size) unless another more specific selector indicates that an element should use different values for these same properties.

It is slightly different from applying default styles to the <body> element because the universal selector applies to every element and does not rely on the property inherited from the rules that apply to the <body> element.

The Type Selector

The type selector matches all the elements specified in the comma-delimited list. It enables you to apply the same rules to several elements. For example, if you want to apply the same rules to different sized heading elements, the following would match all h1, h2, and h3 elements:

h1, h2, h3 {}The Class Selector

The class selector enables you to match a rule with an element (or elements) carrying a class attribute whose value matches the one you specify in the class selector. For example, imagine you have an <aside> element with a class attribute whose value is BackgroundNote, like so:

<aside class="BackgroundNote">This paragraph contains an aside.</aside>You can use a class selector in one of two ways here. One way is to simply assign a rule that applies to any element that has a class attribute whose value is BackgroundNote, like so, preceding the value of the class attribute with a period or full stop:

.BackgroundNote {}Or you can create a selector that selects only the <aside> elements that carry a class attribute with a value of BackgroundNote (not other elements) like so:

aside.BackgroundNote {}If you have several elements that can all carry a class attribute with the same value (for example, an <aside> element and a <div> element could both use the class attribute with the same value) and you want the content of these elements to display in the same manner, use the former notation. If the styles you define are specific to just the <aside> element whose class attribute has a value of BackgroundNote, use the latter notation.

A class attribute can also contain several values separated by a space, for example:

<p class="important code">You can use the following syntax to indicate an element that has a class attribute whose value contains both important and code. (Although, IE7 was the first version of Internet Explorer to support this syntax.)

p.important.code {}The ID Selector

The id selector works just like a class selector but works on the value of id attributes. Rather than using a period or full stop before the value of the id attribute, you use a hash or pound sign (#). So an element with an id attribute whose value is abstract can be identified with this selector.

#abstractBecause the value of an id attribute should be unique within a document, this selector should apply only to the content of one element. (And you should not need to specify the element name.)

The Child Selector

The child selector matches an element that is a direct child of another. In this case it matches any <b> elements that are direct children of <td> elements. The names of the two elements are separated by a greater-than symbol (>) to indicate that b is a child of td, which is referred to as a combinator:

td>b {}This would enable you to specify a different style for <b> elements that are direct children of the <td> element compared with <b> elements that appear elsewhere in the document.

As a direct child of the <td> element, no other tags would sit between the opening <td> tag and the <b> element. For example, the following selector does not make sense because the <b> element should not be a direct child of a <table> element. (Instead, a <tr> element is more likely to be the direct child of a <table> element.)

table>b {}IE7 was the first version of Internet Explorer to support the child selector.

The Descendant Selector

The descendant selector matches an element type that is a descendant of another specified element (or nested inside another specified element), not just a direct child. Although the greater-than symbol is the combinator for the child selector, for the descendent selector the combinator is the space. Look at this example:

table b {}In this case, the selector matches any <b> element that is a child of the <table> element, which means it would apply to <b> elements both in <td> and <th> elements.

This is a contrast to the child selector because it applies to all the children of the <table> element, rather than just the direct children.

The Adjacent Sibling Selector

An adjacent sibling selector matches an element type that is the next sibling of another. For example, if you want to make the first paragraph after any level 1 heading a different style from other <p> elements, you can use the adjacent sibling selector like so to specify rules for just the first <p> element to come after any <h1> element:

h1+p {}IE7 was the first version of Internet Explorer to support the adjacent sibling selector.

The General Sibling Selector

The general sibling selector matches an element type that is a sibling of another; although, it does not need to be the directly preceding element. So, if you have two <p> elements that are siblings of an <h1> element, they would both use the rules of this selector.

h1~p {}The general sibling selector is part of CSS3, which you’ll learn more about in Chapter 9. IE7 was the first version of Internet Explorer to support the general sibling selector, and Firefox 2 was the first version of Firefox to support it.

Using Child and Sibling Selectors to Reduce Dependence on Classes in Markup

The child and adjacent sibling selectors are both important because they can reduce the number of class attributes you need to add into an HTML document.

It is easy to add classes for all kinds of eventualities. For example, if you want the first paragraph after an <h1> element to show in bold, you might be tempted to add a class attribute to the first <p> element after every <h1> element. Although this works, your markup can be littered with all kinds of classes that are only there to make it easier to control the presentation of the pages.

If you then decide you wanted the first two <p> elements after every <h1> element to be bold, you might go back and add in new class attributes for the second <p> elements after every <h1> element. So the child and adjacent sibling selectors add a lot of flexibility to how you style documents and can make for much cleaner markup.

Look at the following HTML content (ch07_eg19.html):

<p>Paragraph One: not inside a div element.</p>

<div>

<p>Paragraph One: inside a div element</p>

<p>Paragraph Two: inside a div element </p>

<p>Paragraph Three: inside a div element </p>

<p>Paragraph Four: inside a div element </p>

<p>Paragraph Five: inside a div element </p>

</div>Using the child and adjacent sibling selectors only, you can create a page that looks like the one shown in Figure 7-22.

The three different paragraph styles are:

- The first paragraph has no border or background color.

- The paragraphs inside the <div> element all have borders.

- The last three paragraphs have a gray background and border.

The different paragraph styles are not specified with three different classes, but rather one rule controls the font used for all paragraphs (ch07_eg19.css):

p {

font-family : arial, verdana, sans-serif;

}The following is the second rule for any paragraph that is a child of a <div> element. (Because the first paragraph is not inside a <div> element, the rule does not apply to the first paragraph.)

div>p {

border : 1px solid #000000;

}The third rule matches any paragraph that is also a third consecutive <p> element. (Because the fourth and fifth <p> elements have two previous <p> elements, this rule applies to them and the third <p> element inside the <div>.)

p+p+p {

background-color : #999999;

}Remember that this example cannot work in IE6 or earlier versions of Internet Explorer because these selectors were first introduced in IE7.

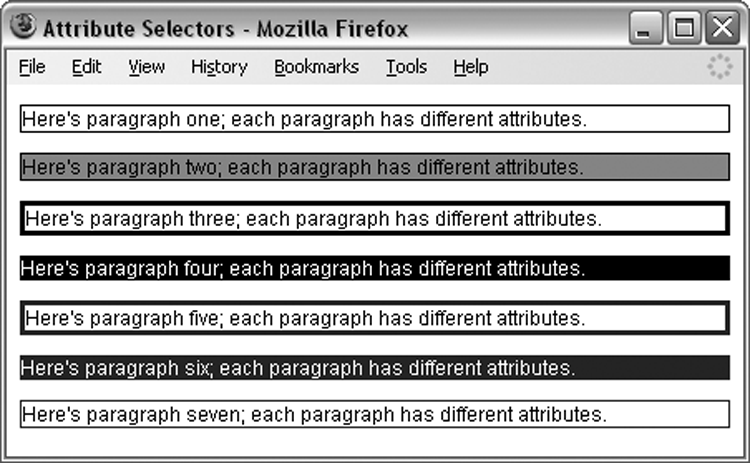

Attribute Selectors

Attribute selectors enable you to use the attributes that an element carries, and their values, in the selector. There are several types of attribute selectors, and they enable complex ways to select elements in a document.

The use of attribute selectors is fairly limited because they have been supported only in the latest versions of browsers. Some of the attribute selectors in Table 7-11 are from CSS3, which you’ll learn more about in Chapter 9.

Table 7-11: CSS Attribute Selectors

| Name | Example | Matches |

| Existence selector | p[id] | Any <p> element carrying an attribute called id. |

| Equality selector | p[id="summary"] | Any <p> element carrying an attribute called id whose value is summary. |

| Space selector | p[class~="HTML"] | Any <p> element carrying an attribute called class, whose value is a list of space-separated words, one of which is exactly the same as HTML. |

| Hyphen selector | p[language|="en"] | Any <p> element carrying an attribute called language whose value begins with en and is followed with a hyphen. (This particular selector is designed for use with language attributes.) |

| Prefix selector (CSS3) | p[attr^"b"] | Any <p> element carrying any attribute whose value begins with b (CSS3). |

| Substring selector (CSS3) | p[attr*"on"] | Any <p> element carrying any attribute whose value contains the letters on (CSS3). |

| Suffix selector (CSS3) | p[attr$"x"] | Any <p> element carrying any attribute whose value ends in the letter x (CSS3). |

Internet Explorer implemented these attribute selectors in IE7. Firefox started to support them in Firefox 2.

Now look at an example of using these attribute selectors. Here are seven different paragraph elements, each carrying different attributes/attribute values (ch07_eg20.html):

<p id="introduction">Here’s paragraph one; each paragraph has different

attributes.</p>

<p id="summary">Here’s paragraph two; each paragraph has different attributes.</p>

<p class="important HTML">Here’s paragraph three; each paragraph has different

attributes.</p>

<p language="en-us">Here’s paragraph four; each paragraph has different

attributes.</p>

<p class="begins">Here’s paragraph five; each paragraph has different

attributes.</p>

<p class="contains">Here’s paragraph six; each paragraph has different

attributes.</p>

<p class="suffix">Here’s paragraph seven; each paragraph has different

attributes.</p>Now look at a CSS style sheet that uses attribute selectors to associate different style rules with each of these elements (ch07_eg20.css):

p[id] {

border : 1px solid #000000;

}

p[id="summary"] {

background-color : #999999;

}

p[class~="HTML"] {

border : 3px solid #000000;

}

p[language|="en"] {

color : #ffffff;

background-color : #000000;

}

p[class^="b"]{

border : 3px solid #333333;

}

p[class*="on"] {

color : #ffffff; background-color:#333333;

}

p[class$="x"] {

border : 1px solid #333333;

}You can see the result in Firefox 3.0 in Figure 7-23.

All selectors should match the case of the element name that they are supposed to match.

As a general rule, the latest versions of Chrome, Safari, Firefox, and Internet Explorer 9+ support all the CSS selectors you will encounter in this book. IE8 was the first version of Internet Explorer to support the CSS2 selectors. Older versions of Internet Explorer are problematic except for the most basic selectors. For a complete list, check the support table from Browse Em All found at http://www.browseemall.com/Blog/post/2012/03/16/The-cross-browser-compatibility-guide-CSS-selectors-browser-support.aspx.

Lengths

You have already seen that the values of some CSS properties are given as lengths (such as the size of fonts, height of lines of text, and gaps between words and letters), and you will come across more properties whose values are expressed as lengths throughout the chapters on CSS. So, now take a moment to look at the three ways lengths can be specified in CSS:

- Relative units

- Absolute units

- Percentages

Relative Units

There are three types of relative units: the pixel (px), which relates to the resolution of the screen, and the em and ex, both of which relate to the size of fonts.

px

The pixel, referred to in code as px, is by far the most commonly used unit of length in CSS. A pixel is the smallest unit of resolution on a screen, and if you look closely at your screen, you might just see the square dots that are the pixels.

Technically, the size of a layout that uses pixels as a unit of measurement can depend upon the viewing medium, which is why it is counted as a relative unit.

Most computer screens have a resolution of 72 dots per inch (dpi), but laser and bubble jet printers are usually set with a higher resolution—for example, 300 dpi. In contrast, mobile devices can have a lower resolution than computer screens or (for some smartphones such as the iPhone) a higher resolution.

So, a table that is 500 pixels wide could be 9.9444 inches wide on a 72 dpi screen, 1.666 inches wide at 300 dpi, or 13.888 inches wide on a 32 dpi screen. (And a screen that is only 32 dpi is unlikely to be that much more than 13 inches wide.)

In reality, when you print a web page from your browser, it adjusts the pixels to present a readable version of the document. CSS recommends that in such cases user agents rescale pixel units so that when a document is read at arm’s length 1 pixel would correspond to approximately 0.28 mm or 1/90 of an inch.

em

An em is equivalent to the height of the current font, and because the size of fonts can vary throughout a document, the height of the em unit can be different in different parts of the document. Furthermore, because users can change the size of text in their browser, the em unit can vary in relation to the size of the text that the user has selected.

This means that the em unit is most commonly used for measurements of elements that contain text and for controlling spacing between text. (For example, you can use it in the line-height property to set the gaps between lines of text in relation to their height.)

Although the em unit is equivalent to the height of a font, it is often thought to have derived from the width of a lowercase m; you may also hear the term en, which equates to half an em.

ex

The ex should be the height of a lowercase x. Because different fonts have different proportions, the ex is related to the font size and the type of font. In Figure 7-24, you can see the x in the Courier typeface is smaller than the x in the Impact typeface.

New Relative Units: rem, vh, and vw

You may encounter three new relative units introduced in the CSS Values and Units Candidate Recommendation (http://www.w3.org/TR/css3-values/): rem, vh, and vw.

- rem units are equal to the font size of the root element—a “root em.” This allows you to use font-relative sizing with less complexity than with the traditional path of em units and percentage-based heights/widths.

- vh units are equal to 1 percent of the viewport height. vw units are equal to 1 percent of the viewport width. This allows for viewport-relative layouts. If the viewport changes (for example, in the change from portrait to landscape on a tablet), these units scale proportionally.

rem units are supported in IE9+ and the latest versions of the other major desktop browsers. As of this writing vh and vw support is only in IE10+, Chrome 20+, Firefox 19+, Safari 6+, and with partial support in Opera 12.5.

Absolute Units

Generally speaking, absolute units are used far less than relative units. (And you rarely come across designs that use these units of measurement.) Table 7-12 shows the absolute units used in some CSS properties.

Table 7-12: Absolute Units in CSS

| Unit | Full Name |

| pt | Point |

| pc | Pica |

| in | Inch |

| cm | Centimeter |

| mm | Millimeter |

You shouldn’t need clarification for inches, millimeters, or centimeters, but the other two are more interesting. A point is 1/72 of an inch (the same as a pixel in most computer screen resolutions), and a pica is 1/12 of an inch (12 points). Typographers tend to use points to measure font sizes and leading (the gaps between lines), whereas picas measure line lengths.

Percentages

Percentages give a value in relation to another value. For example, if your page contains only two paragraphs, and you want each to take up one-half of the width of the browser, you might give the paragraphs a width property with a value of 50%. However, if the <p> element were inside another element that you knew was 500 pixels wide, they would take up 50 percent of the width of that containing element (or 250 pixels) each.

Introducing the Box Model

The box model is an important concept in CSS because it determines how elements are positioned within the browser window. It gets its name because CSS treats every element as if it were in a box.

As you can see in Table 7-13, every box has three properties you must be aware of.

Table 7-13: Important Box Model Properties

| Property | Description |

| border | Even if you cannot see it, every box has a border. This separates the edge of one box from other surrounding boxes. |

| margin | The margin is the distance between the border of a box and the box next to it. |

| padding | This padding is the space between the content of the box and its border. |

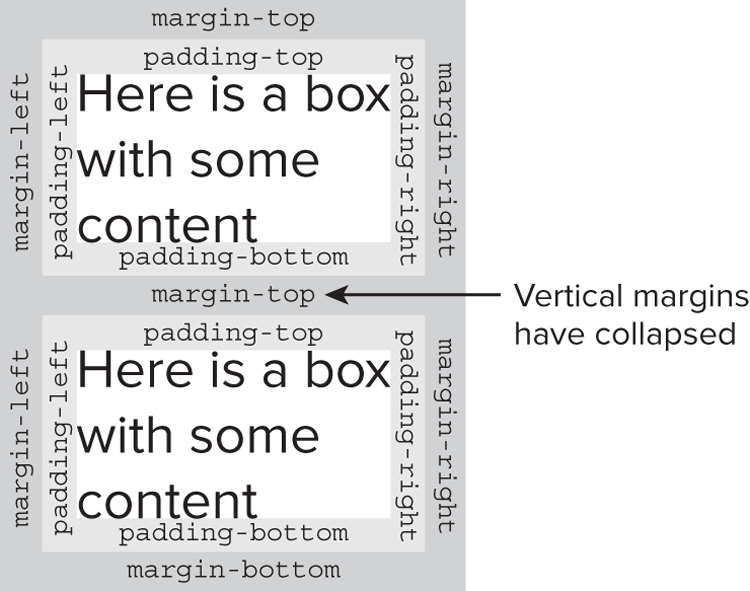

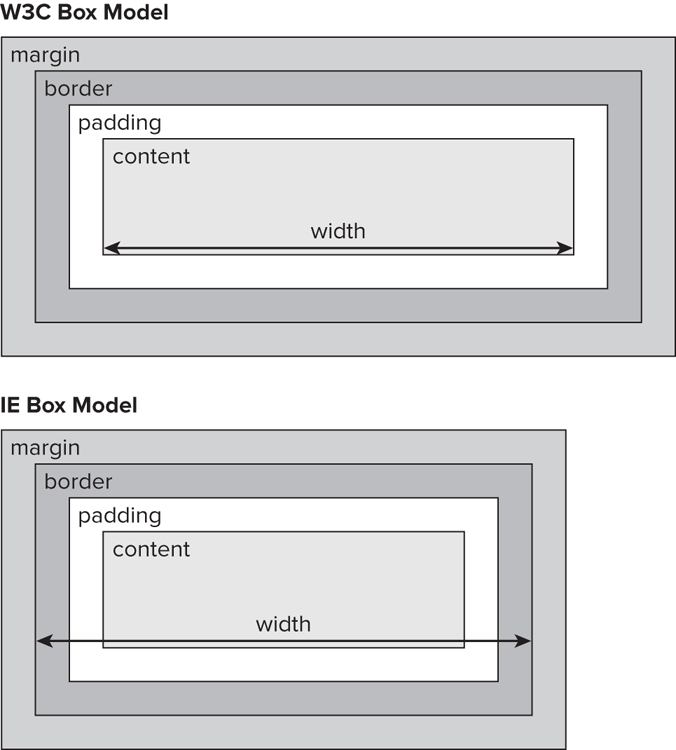

You can get a better idea of these properties in Figure 7-25, which shows the various parts of the box. (The black line is the border.)

You can use CSS to individually control the border, margin, and padding on each side of a box; you can specify a different width, line-style, and color for each side of the box’s border.

The padding and margin properties are especially important in creating what designers refer to as white space; this is the space between the various parts of the page. For example, if you have a box with a black border and the box contains black text, you would not want the text to touch the border because it would make the text harder to read. Giving the box padding helps separate the text from the line around the edge.

Meanwhile, suppose you have two boxes next to each other, both with borders. If there is not a margin between them, the boxes will run into each other, and the line where the boxes meet could look thicker than the other lines.

There is, however, an interesting issue with margins: When a bottom margin of one element meets the top margin of another, only the larger of the two shows. (If they are the same size, the margin is equivalent to the size of the larger of the two margins.) Figure 7-26 shows the vertical margins of two adjacent boxes collapsing. (This applies only to vertical margins; the same is not true for left and right margins.)

To understand how the box model works with elements, look at the example in the next section.

An Example Illustrating the Box Model

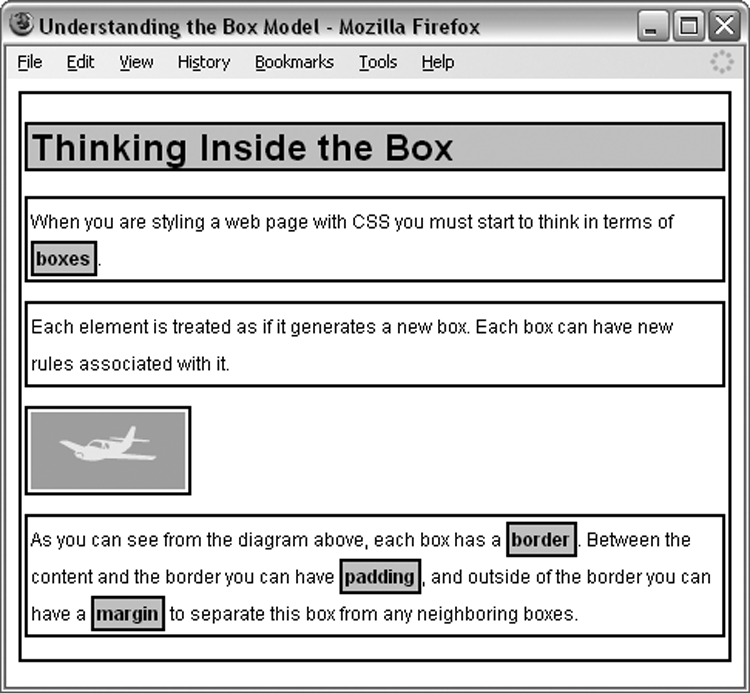

To illustrate the box model, you can add a border to each of the elements in a web page. The <body> element creates one box that contains the whole page, and inside that box each heading, paragraph, image, or link creates another box. First, here is the HTML for the page (ch07_eg21.html):

<h1>Thinking Inside the Box</h1>

<p class="description">When you are styling a web page with CSS you

must start to think in terms of <b>boxes</b>.</p>

<p>Each element is treated as if it generates a new box. Each box can have

new rules associated with it.</p>

<img src="images/boxmodel.gif" alt="How CSS treats a box">

<p>As you can see from the diagram above, each box has a <b>border</b>.

Between the content and the border you can have <b>padding</b>, and

outside of the border you can have a <b>margin</b> to separate this box

from any neighboring boxes.</p>Using just one CSS rule, you can see how each element involved with the body of the document—<body>, <h2>, <p>, <img>, and <b>—is treated as if it were in a separate box. You can do this by adding a CSS rule that adds a border around each of these elements. You learn more about these properties shortly (ch07_eg21.css).

body, h1, p, img, b {

border-style : solid;

border-width : 2px;

border-color : #000000;

padding:2px;

}Each box can be presented differently. For example, you can give the <h1> and <bold> elements a gray background to help distinguish them from other elements.

h1, b {

background-color : #cccccc;

}Figure 7-27 shows you what this page looks like in a browser. Although it is not too attractive, the lines show you the borders of the boxes (and demonstrate how boxes are created for each element).

You may remember from Chapter 1 that there is a difference between block-level elements and inline elements. The difference becomes quite important when working with CSS because it determines how each box displays.

- The <h1> and <p> elements are examples of block-level elements. Each block-level element starts on a new line, and the box around a block-level element takes up the full width of the browser (or the full width of the element it sits inside).

- The <b> element is an example of an inline element. Its box sits in the middle of the paragraph and it does not take up the width of a whole line. (It flows within its containing element.)

The <img> element may look like it is a block-level element because it starts on its own line, but it is actually an inline element. You can tell this because the border around it takes up only the width of the image; if it were a block-level element, the border would reach across the full width of the browser. The image is on its own line only because the elements on either side of it are block-level elements. (And therefore the surrounding elements appear on their own lines.)

Now that you know how each element is treated as if it were in its own box, look at the properties that control the borders, padding, and margins for each box.

The border Properties

The border properties enable you to specify how the border of the box representing an element should look. There are three properties of a border you can change:

- border-color to indicate the color a border should be

- border-style to indicate whether a border should be a solid, dashed, or double line, or one of the other possible values

- border-width to indicate the width a border should be

The border-color Property

The border-color property enables you to change the color of the border surrounding a box, for example:

p {

border-color : #fc00f000;

}The value can be any valid color value. (Colors are discussed in greater detail in Appendix D.)

You can individually change the color of the bottom, left, top, and right sides of a box’s border using the following properties:

- border-bottom-color

- border-right-color

- border-top-color

- border-left-color

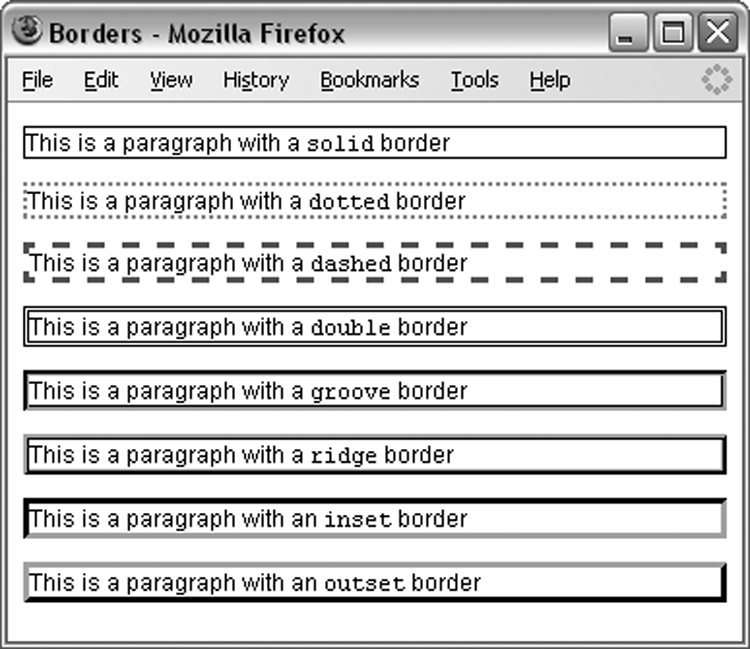

The border-style Property

The border-style property enables you to specify the line style of the border:

p {

border-style : solid;

}The default value for this property is none, so no border would be shown automatically. Table 7-14 shows the possible values.

Table 7-14: Values for the border-style Property

| Value | Description |

| none | There is no border. (Equivalent of border-width:0;) |

| solid | The border is a single solid line. |

| dotted | The border is a series of dots. |

| dashed | The border is a series of short lines. |

| double | The border is two solid lines; the value of the border-width property creates the sum of the two lines and the space between them. |

| groove | The border looks as though it is carved into the page. |

| ridge | The border looks the opposite of groove. |

| inset | The border makes the box look like it is embedded in the page. |

| outset | The border makes the box look like it is coming out of the canvas. |

| hidden | Same as none, except in terms of border-conflict resolution for table elements. |

Figure 7-28 shows an example of what each of these would look like (taken from ch07_eg22.html). Note that even though the last four examples in Figure 7-27 look similar, they are different, and you can try them for yourself with the download code for this example.

You can individually change the style of the bottom, right, top, and left borders of a box using the following properties:

- border-bottom-style

- border-right-style

- border-top-style

- border-left-style

The border-width Property

The border-width property enables you to set the width of your borders; usually the width is specified in pixels.

p {

border-style : solid;

border-width : 4px;

}The value of the border-width property cannot be given as a percentage; although, you could use any absolute unit or relative unit, or one of the following values:

- thin

- medium

- thick

The actual width of the thin, medium, and thick values are not specified in the CSS recommendation in terms of pixels, so the actual width that corresponds to these keywords is dependent on the browser.

You can individually change the width of the bottom, right, top, and left borders of a box using the following properties:

- border-bottom-width

- border-right-width

- border-top-width

- border-left-width

Expressing border Properties Using Shorthand

The border property enables you to specify color, style, and width of lines in one property:

p {

border : 4px solid red;

}If you use this shorthand, the values should not have anything (other than a space) between them. You can also specify the color, style, and width of lines individually for each side of the box in the same way using these properties:

- border-bottom

- border-top

- border-left

- border-right

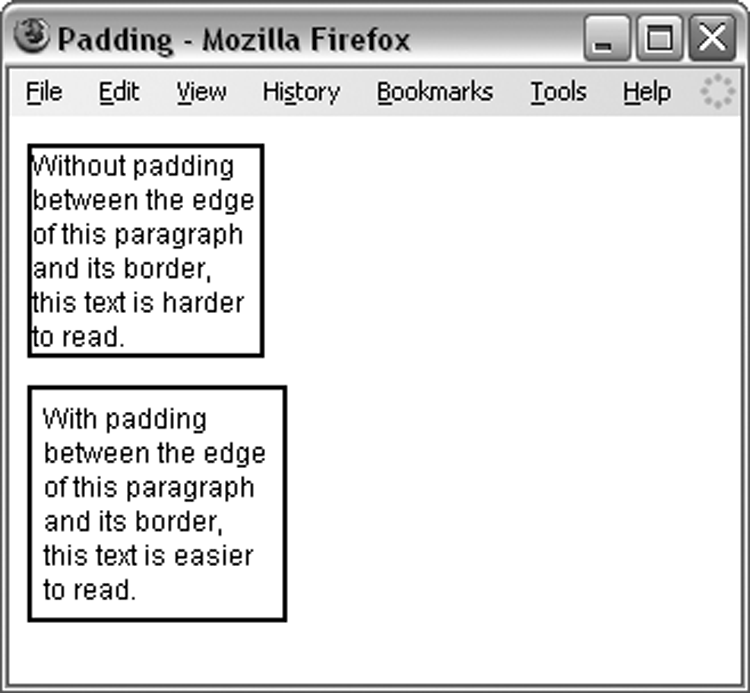

The padding Property

The padding property enables you to specify how much space should appear between the content of an element and its border:

td {

padding : 5px;

}The value of this property is most often specified in pixels. Although, it can use any of the units of length you met earlier, a percentage, or the word inherit.

The padding of an element does not inherit by default, so if the <body> element has a padding property with a value of 50 pixels, this does not automatically apply to all other elements inside it. If the value inherit is applied to any elements, only then can they have the same padding as their parent elements.

If a percentage is used, the percentage is of the containing box, and if the value of 10 percent is specified, there would be 5 percent of each side of the box as padding.

You can specify different amounts of padding inside each side of a box using the following properties:

- padding-bottom

- padding-top

- padding-left

- padding-right

The padding attribute is especially helpful to create white space between the content of an element and any border it has. Look at the following two paragraphs in Figure 7-29.

If you look at the CSS rules for these two paragraph elements, you can see that by default the first paragraph has no padding. It must be specified if you want a gap like the one shown in the second paragraph (ch07_eg23.css).

.a, .b {

border-style : solid;

border-color : #000000;

border-width : 2px;

width : 100px;

}

.b {

Padding : 5px;

}Sometimes, an element might not have a visible border, but it has a background color or pattern. In such cases giving the box some padding can help make your design more attractive.

The margin Property

The margin property controls the gap between boxes, and its value is either a length, a percentage, or inherit, each of which has exactly the same meaning as it did for the padding property you just saw.

p {

margin:20px;

}As with the padding property, the values of the margin property are not inherited by child elements unless you use the value inherit.

Also, remember that when one box sits on top of another box, only the larger of the two margins shows (or if both are equal, the size of one margin).

You can also set different values for the margin on each side of the box using the following properties:

- margin-bottom

- margin-top

- margin-left

- margin-right

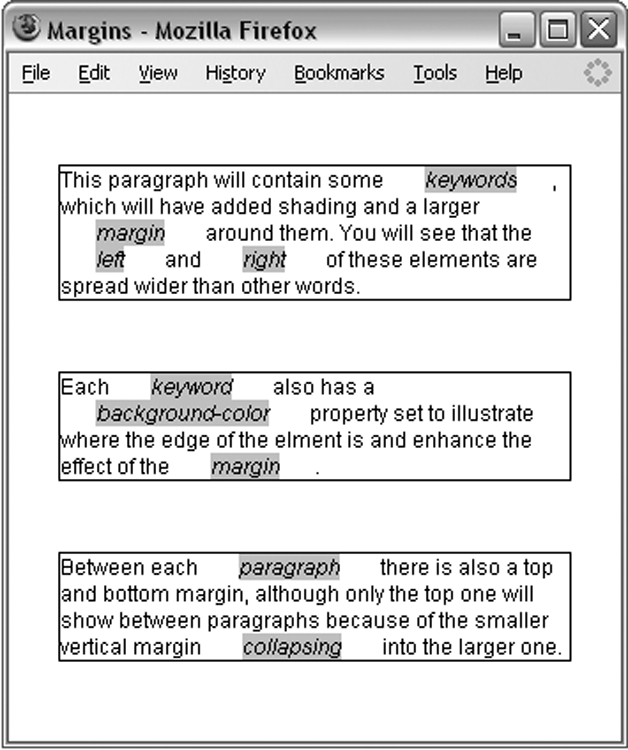

If you look at the following example (see Figure 7-30, which shows ch07_eg24.html), you can see three paragraphs, which look as if they are spaced equally. However, they have taller margins on the top than the bottom, and therefore where two boxes meet, the bottom margin is ignored—the margins are collapsed. (This happens only to the vertical margins, not the left and right margins.)

The example also shows how to set the left and right margins on the side of inline elements—where you see the highlighted words. Again, this is not the most attractive example, but it illustrates how both block and inline boxes use margins.

The words in the paragraphs that are emphasized using the <em> element have margin-left and margin-right properties set. Because these <em> elements also have a background color set, you can actually see how the margins to the left and the right separate the words from the surrounding words (refer to Figure 7-30).

Here are the rules from ch07_eg24.css:

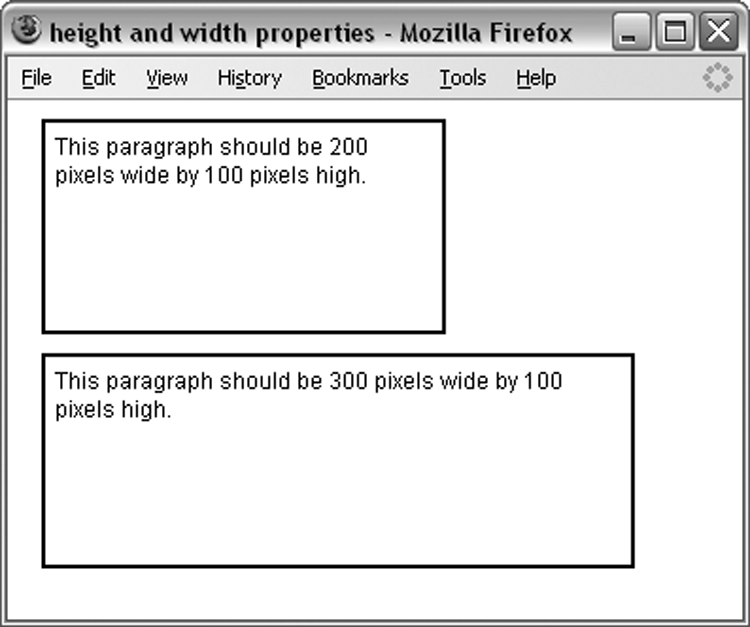

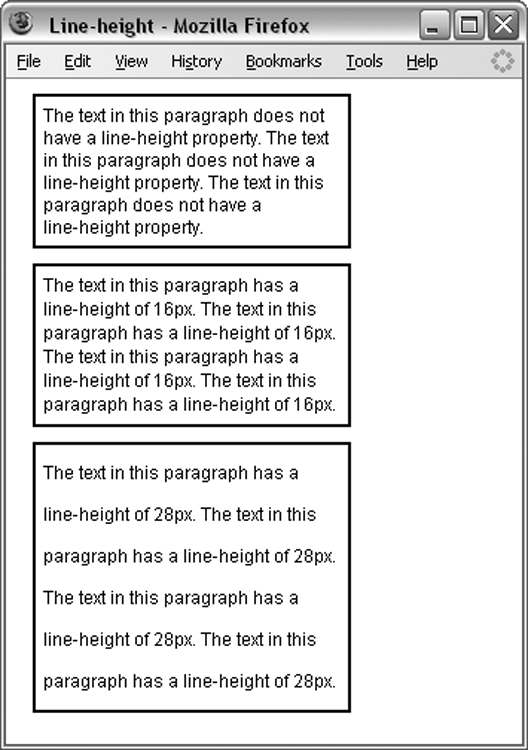

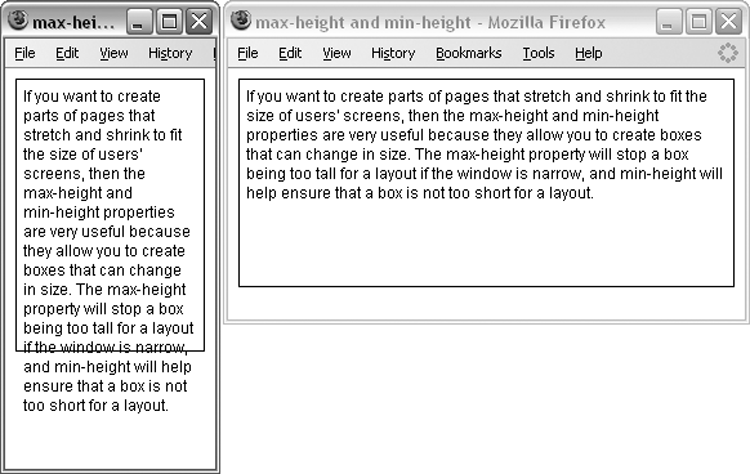

body {