Investigating the target

Introduction

You have found the ideal target, spent a long time convincing your board and financiers that it is a good buy; you have given serious thought to what you are going to do with it once it is yours and you have managed to get the seller to agree to sell. This is where it starts to get scary. How do you know that this really is what the owner cracks it up to be? How do you know it is the seller’s to sell? How do you know it does not have the corporate equivalent of dry rot? How can you be sure that all the plans you have to recoup that fancy price you are about to pay are realistic? The prospect of having to part with hard cash focuses the mind like nothing else can and one of the things you will most definitely want to do now is check out your intended purchase while you can still change your mind. In the trade this checking-out is called due diligence.

What is due diligence about?

Due diligence is not just about looking for black holes or skeletons in the cupboard. Although really it includes both of these, it should be carried out with the aim of making the deal successful. Due diligence is about three things:

- Checking that the target company is as presented to you and what you think you are buying

- Confirming the value you have put on the business

- Filling the gaps in your integration plan.

When should you do it?

For a due diligence investigation to be meaningful it must be conducted before a buyer is committed to a deal. Figure 6.1 illustrates the typical process of an acquisition.

Due diligence is usually conducted after heads of terms have been signed, because that signals that both sides are serious about continuing. The buyer therefore has every reason to believe that the time and money spent on due diligence will not be wasted. At this point a buyer typically enters into a period of exclusivity for 8–16 weeks.

There is no need to start all investigations at the same time. It is often best to kick off the commercial investigation as soon as possible because it can have an impact on the rest of the process. The legal investigations are started once some of the initial commercial and financial findings have become clear.

Be prepared for obstacles

Do not think that a buyer’s willingness to sell will make due diligence easy. This is a typically Anglo-Saxon process and the relationship between buyer and seller is a dynamic mix of shared and opposed interests. The seller has no duty of care to the buyer so it is in the buyer’s interest to have as much information as possible before being bound. Precisely the opposite applies to the seller because information means power. Sellers, and in particular their advisers who often do not get paid unless the transaction completes, are keen to see a rapid completion, so they set a tight timetable. Other legal systems resolve the buyer–seller conflict in different ways. Generally, in continental Europe the buyer has to commit on the basis of a less thorough investigation, but the seller does owe a duty of care.

Time pressure is being exacerbated by a number of factors. Sellers are tending to grant shorter periods of exclusivity. Increasingly sellers will only release information once the acquirer has signed a confidentiality agreement. These agreements are becoming more and more onerous. They can take time to negotiate, holding up the due diligence exercise. Even with a confidentiality agreement in place, the seller may wish to hold back sensitive commercial information for the first part, or even all, of the process. Some sellers even initiate a ‘contract race’.

But remember, there is no timetable in the world that cannot be extended for a serious buyer.

The seller may wish to keep the proposed sale confidential from employees. If this includes top management, or if the seller decides that top management should not be interviewed for any other reason, then it makes due diligence very difficult. The seller may prevent any personal visits to the target’s premises, but orchestrate a management presentation during which the buyer can meet the team. It is only with the involvement of top executives that the acquirer can obtain much of the information it needs about the business. If the access is too limited, or the management presentation is too tightly stage-managed, the acquirer should be prepared to walk away.

Finally, the acquirer should ask the seller whether the target company is bound by any confidentiality obligations to third parties. These might exist, for example, as a consequence of joint venture or other partnership agreements. They may prevent the target company disclosing critical business information without the partner’s agreement.

Remember: the target will have prepared

Corporate finance advisers are highly motivated to complete transactions; this inevitably means that they will have coached their clients on how best to present their business. They know that companies for sale can be made more attractive and achieve a better price through some judicious grooming. You should also bear in mind that any saleable company is likely to receive one or more unsolicited approaches from prospective purchasers each year, which means that if a company has put itself up for sale, the timing is probably right.

Preparation or grooming can take months or even a couple of years. The amount done depends on the time available in which to do it. The following is a list of the areas that might have been covered before a buyer gets a close look at the business:

- Selecting the right buyers

- The trading record

- Forecasts

- Control systems

- Business risks

- Management and staff

- The asset base

- Loose ends.

Selecting the ‘right’ buyers

The ‘right’ buyer is one who can complete quickly for the best price. A lot of the value added by corporate finance comes from finding purchasers with the most to gain from the transaction, thus securing the best deal for the seller. A good adviser will have selected no more than 5–10 possible purchasers from its extensive investigations. If you get to exclusivity, you will be one of the strongest candidates from those initially selected. However, any well-advised seller will keep at least one buyer in reserve after exclusivity has been granted, just in case.

The trading record

A company for sale needs to provide a demonstrable opportunity for sustained, medium-term, profit growth. If grooming starts early enough it is possible to manipulate sales, and profit, for example by delaying invoices over a year-end or carefully timing items of major expenditure, so that the seller can show the gently rising trend beloved of acquirers. Provisions will have been carefully reviewed. There is no point in a seller just releasing excessive provisions all in one go because a buyer will simply not include them in its valuation. Excessive provisions will have been slowly released over a few years.

On top of this, you can bet that everything possible has been done to maximise profit in the current and preceding financial year. Although sellers know that buyers are paying for the future, they also know that the forecast for this year plus last year’s actuals are going to play a major part in the valuation. One recent transaction went no further than the first day of due diligence because the accountants found out that the target company had no forward orders despite the fact that the buyer fully understood that this was a business with a lumpy order book. Other deals have been terminated when buyers discovered that major contracts had been lost, even though there was every chance that the lost business would be recouped fairly quickly.

Any seller will defer discretionary expenditure that does not have a payback before completion. Office walls will remain unpainted and the carpets threadbare. One engineering company managed to delay repairing its factory roof prior to sale by placing netting underneath to catch the falling glass. Other costs which can be reduced over the short term include advertising, not replacing staff who leave, taking non-working relatives off the payroll, keeping personal expenses to the absolute minimum, not starting costly R&D projects and not setting up new ventures that have little prospect of breaking even before completion. Any non-business costs will be avoided.

A pre-sale price rise may be another means of improving the trading record, especially if prices have not been reviewed for some time. A leading supplier of art materials had reviewed its prices six months before due diligence and under the guise of introducing consistency of pricing across a range of some 6,000 items, managed to increase prices by stealth by something like twice the rate of inflation. There was no way another across-the-board price rise could be contemplated for some time as customer perceptions were that the target’s prices were high relative to the market, albeit without fully understanding how this state of affairs had come about.

Finally, the seller and its advisers should have reviewed accounting policies so that the buyer does not have an excuse to revise profits, and therefore price, downwards by adjusting any policy which inflates profit while ignoring those that do not.

Forecasts

The seller should have put together a forecast for the next two years’ profit and cash flow. The current year forecast will be presented in great detail and will be achievable. Forecasts will not normally be unrealistically high because a failed sale damages value.

As a final means of talking up the future, vendors will be coached to look at the deal from the buyer’s perspective. As a result they will assess the synergies available to each prospective purchaser and normally be ready to volunteer their thoughts on achievable cost savings – not out of altruism but with the aim of sharing them. They will also put a value on their own company’s rarity and be aware of sector-specific valuation benchmarks (see Chapter 7).

Control systems

Companies for sale will want to give the appearance of being efficiently run and well controlled. Sellers know that prospective purchasers will want to compare monthly budgeted performance with actual performance over the past three years. Once a business decides to sell, therefore, it will need to put a system of budgets and monthly management accounts in place if one does not already exist.

Business risks

Businesses which rely on a small number of customers or suppliers increase their risk of losing sales, suddenly running short of materials or being squeezed on cost. An essential part of pre-sale grooming is to diversify these risks by finding new customers, new lines of business and new sources of supply. Due diligence should concern itself with the robustness of such relationships. An example of a case where this had not been done, and which came close to scuppering a deal, was a company which relied on two raw materials. Demand for its own products was suddenly booming, driven by new legislation. What the target company had not done was to secure a sufficient supply of raw materials. This was against a background where raw materials suppliers had spent years waiting for a price rise which never came. Their patience was now exhausted. Old plant was being decommissioned with the result that the demand/supply balance was tightening very quickly. If demand continued on its present trajectory raw materials would be rationed, thus denying the target its ability to capitalise on its growing market. Fortunately, the target was of sufficient standing to be able to secure sufficient raw material, but it was a close run thing.

Management and staff

Depending on the acquirer and reasons for the deal, tying in the right management to the target company can be the most important factor in a deal going ahead. Before the company is officially put up for sale, the seller should have done all it could to present a stable and committed management team. If it is a business that has relied on the disproportionate talents of one person, usually the founder, who is not going to continue with the business once it has been sold, strenuous efforts will have been made over an extended time frame to hand the day-to-day running of the business to the next generation. If this is not the case buyers should wonder what strength and depth there is in the management team.

The founder of a publishing business claimed that he arrived at 10 a.m. every day and left before lunch, only coming in to open the mail. According to him, the business no longer needed him and his wife was giving him considerable ‘earache’ because in her view he should have been spending as much time as possible with his young family. Common sense told the would-be buyer that this was not the whole truth. Why did he insist on opening the mail? Why could this not be delegated to his PA? The answer was he was the only person in the company who had a view of the big picture and opening the mail made sure he kept things this way. Furthermore the business was highly dependent on a large and unstable sales force. The founder’s biggest contribution to the business was sales force recruitment and training – activities which took place on a sufficiently irregular basis for it to seem he was only there between 10 a.m. and 1 p.m. every day. The reality was that he would also have a week of frantic activity and long hours every quarter or so. Finally, there was no management team beneath him. Contracts were administered by a secretary, the finance director was part-time and that was the extent of second-tier management.

Even with a strong management team tied in when a deal is done, it is a sad fact that the majority of senior managers will have departed within two years of the transaction. This is why sellers are encouraged by their advisers to strengthen the second management tier as well as strengthening the top team.

The asset base

Buyers will value the business on its prospects. Non-business and surplus assets will have zero value in their eyes. The well-advised seller will make sure all underutilised and redundant assets, including investments, are sold off. Surplus land and freehold properties are the most obvious candidates for disposal but a looming sale removes the case for holding onto any assets on the off-chance that they might come in handy one day. It also frees up space which can be presented to prospective purchasers as giving room for expansion. Any stocks that are fully written down will be disposed of. These too are surplus assets which have zero value to the buyer.

There will usually be differences between the value of assets on the balance sheet and their market value. A seller will be advised to have assets revalued to avoid either underselling or ‘pound for pound’ adjustments by a buyer whose own revaluations suggest that assets are overvalued. This applies to working capital too. To avoid the risk of having to pay for missing working capital on a pound-for-pound basis, sellers will have reviewed:

- Stock provisions

- Old debts which might never be paid

- Bad debt provisions.

They may also have paid a special dividend to strip out any surplus cash. As far as a seller is concerned, surplus cash will only be valued at face value and may not be valued at all if a buyer values the target on the basis of profit.

Loose ends

Enhancing a business in the eyes of prospective purchasers will mean all the legal loose ends should have been tidied up. This would include tidying up group structure, trying to clear up all outstanding litigation, registering trademarks and patents, formalising the contractual position of key staff, checking that the deeds to property are properly registered and that there are going to be no problems with leases or dilapidations. Tax affairs should also be sorted out as soon as a sale is mooted and, if they are not, any buyer has to ask how efficient the target really is. Finally, this might also be the perfect time to buy out minority or joint venture interests, especially if the original rationale for having them as partners has diminished.

Sellers will be encouraged to get bad news on the table early on because they know that the earlier unattractive features are revealed, the less impact they will have on the deal. Given sufficient time and high-calibre people, sellers will arrange the target’s affairs in order to maximise the sale price. This is not to say that a buyer cannot find areas of weakness but it does mean that if they are to be found they will not necessarily be in the most obvious places.

How do I know what due diligence to do?

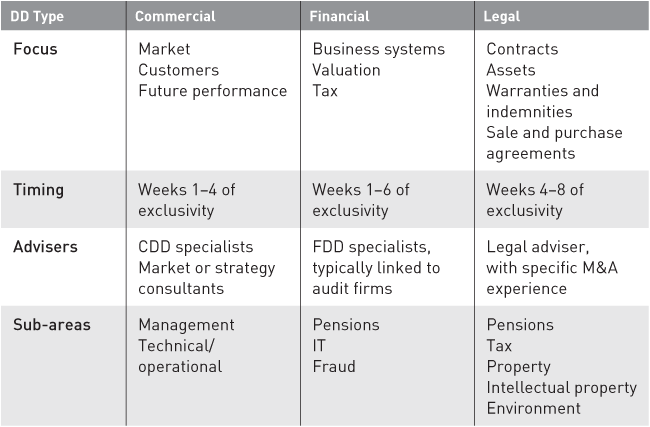

There are three main areas of due diligence – commercial, financial and legal – and a host of sub-specialisms such as tax and pensions. Table 6.1 sets out areas which would typically be covered by different types of due diligence.

There is no right answer to the question of how much due diligence to do. In practice, time, money and the seller’s patience will limit how much you do. You cannot investigate everything, so there is always a risk that you will not cover something that you should have. However, knowing that you can only cover the high points should force you to think about the areas which are the biggest potential risks to a successful transaction. Then you can get the maximum return from due diligence. The worst thing is to grind through the ‘normal procedures’ without understanding what you are trying to achieve.

A myriad of topics may be interesting or useful to cover; but the trick is to focus on what actually matters. That means following the links from your strategy, through the business case for the acquisition, to the factors which will drive or impede the future performance of the acquisition target, both alone and in its combination with its new parent. Experienced acquirers do this and put irrelevant topics to one side. Less perennial acquirers can fall into the trap of trying to ‘find out everything’ about the business and then, exhausted by the process, confusing themselves with the detail.

Preparations before the process starts are a big help. If the acquirer has tracked the market sector and the target over a number of years it is far better equipped to focus on the key issues and move quickly and effectively in the due diligence phase.

Who does due diligence?

The short answer is that you are going to end up employing a host of specialist and expensive advisers, which only goes to underline the point made above about thinking very carefully about what you need.

It is usual for an acquirer to follow through from its original investigations and conduct some of its own due diligence in those areas where it is particularly well-placed to investigate. But acquirers usually also need to use outside advisers because:

- Conducting due diligence is a specialist skill and much can be gained by using advisers who spend all their time doing this type of work. They will do the work more quickly, are more likely to dig out hidden information and know how to minimise disruption to the target company. They should be able to spot difficulties in advance and find ways around them. For example, this could be obtaining hard-to-get information or persuading busy or difficult management teams to cooperate. Experienced and competent advisers will also help to define the scope and then to review it as the process proceeds.

- Advisers bring extra resources. Most acquirers simply do not have skilled resource sitting around on the off-chance of a deal.

- The buyer needs to concentrate on the big picture. Subcontracting most of the detailed due diligence work means a buyer can focus on the really important issues. The disaster that was British and Commonwealth’s purchase of Atlantic Computers was caused precisely because no one had an overview of due diligence.

- The management of the target company may be reluctant to allow access to managers from a competitor or a potential new entrant. They may be more prepared to deal with an independent professional firm.

- The dangers of ‘deal fever’ were mentioned in Chapter 1. Advisers are independent and much less emotionally attached to a deal. It is possible to obtain many of the specialisms listed in Table 6.1 from one source, say one of the large accounting firms. One of the reasons for not doing so is the need for a range of opinions (another is that advisers are not very good outside their core disciplines).

Whilst subcontracting parts of the due diligence almost always makes sense, the acquirer must stay in close contact with various teams. The advisers can benefit from the inputs of their clients and provide input to their strategic thinking and integration planning. Obviously this is very difficult to do at the last minute; it is better to line up internal resources and external advisers in advance.

What do I do?

Next in importance, after knowing what you want, comes knowing from whom you are going to get it, in what form and when. Then you manage the process to make sure it arrives as planned.

Besides managing the seller, the buyer needs to deploy the strongest possible project-management skills. There are numerous strands for the acquirer to coordinate, everyone on both sides of the transaction is busy and there is never enough time in the deal timetable, but the various elements of due diligence must be ‘joined-up’ and tie coherently into the forecasts, the business plan and the integration plan. External advisers must be kept on track. Commercial, financial and legal due diligence teams need their efforts co-ordinating and each team’s work needs continually adjusting in the light of new information. Above all, the buyer needs to make sure there is enough time to digest the information and analysis before making decisions. This is not some clever strategic, legal or financial exercise: it is unadulterated project management.

Get the right team

The right team can make the difference between an excellent due diligence process and something that costs a lot of money to tell you what you already know.

Team members need experience and a mix of business, investigative and analytical skills. Some investors look for sector experience above all else: this is wrong because definitions of sectors are so wide as to be useless in screening prospective advisers. Besides, having someone in a firm with relevant sector experience is no guarantee that he or she will have the right skills for your deal. Due diligence is a process which can be applied to any sector in any industry. In order of importance, therefore, the most important attributes to look for are:

- Experience of preparing due diligence reports

- Experience of the purchaser and a common understanding of objectives

- Experience of the target company’s sector.

The accounting firms are very concerned about liability, leading them to follow strict procedures. This can blunt the edge on analysis while also limiting the extent to which they can share strong opinions. There is a wide variance in the partners at these firms, so the key to success is to find a partner who has a strong commercial outlook and who applies commercial thinking to the numbers. You also want to be able to have a frank conversation, possibly outside of formal meetings, in which you tap into his or her experience and ask the fundamental question: ‘If this was your pension fund that you were investing in this business, would you do so?’ Make it clear that you will not shoot the messenger, otherwise you may only get a bland answer.

Commercial due diligence advisers are less typically concerned about liability than the accountants; this allows them to provide the most commercial advice. Although some of the large accounting firms often try to offer a combined financial and commercial service, the results are rarely as good as claimed in the sales pitch. The commercial work is often watered down due to liability concerns as well as the team’s financial as opposed to strategic focus.

Some lawyers help to get deals done whilst safeguarding the buyer, others seem to get in the way and you can be left wondering whose side they are on. Therefore, when looking for lawyers, it is also advisable to look for creativity and to probe their record of suggesting sensible, commercial solutions to problems.

One law firm set out to assess the top 50 of a target company’s 400 major contracts which were provided in a data room. Its team of juniors religiously copied out all the details of 50 contracts. The acquirer pointed out that there were simply four contract models which the target company used and which had evolved over time. All the legal due diligence (LDD) team had to do was set out the contract types and then note the exceptions.

Other points to watch

Be sensitive

Particularly in private companies and countries where the acquisition process is less well understood, management can be sensitive to due diligence. They may challenge whether it is needed at all – ‘Don’t you trust me?’ Experienced acquirers and their advisers can often win round the seller. They can argue that their investigation will allow the buyer to understand the full value of the business. Equally if a bank will be providing debt, they can point out that full due diligence is a requirement of the lending bank.

Any buyer is well advised to avoid disruption to the target business if only because it might come back and bite. As due diligence processes become more detailed and ever more onerous, they can affect the business negatively. If top management has to attend meetings which add no value to the business and focus on responding to the myriad of information requests, they are unable to deal with customers and other operational challenges. One reason for acquirers to be disappointed by post-deal trading can simply be that the management of the target company had taken its eye off the ball over the preceding weeks and months.

Remember your duty of confidentiality…

The acquirer has a duty of confidentiality implied by English law and on top there will typically be a formal confidentiality agreement. An acquirer who misuses confidential information could be sued for damages or an injunction issued to stop its use of the information.

… and promises you have made…

These may include promises not to solicit any of the target’s customers or employees. They usually bite not only during the due diligence period but also for a stated period after an abortive transaction.

… and the perils of insider dealing

If either the acquirer’s or the seller’s securities are traded on the London Stock Exchange or other securities market, then the proposed transaction may be price sensitive. Insiders should neither deal in the securities nor discuss the transaction with third parties who are likely to deal in the securities until the transaction is made public and is no longer price sensitive.

Commercial due diligence

Commercial due diligence (CDD) goes beyond the historical numbers and gets to the realities of where revenues actually come from and what the future holds for them. It is the investigation of a company’s market, competitive position and prospects. The investigation covers the fundamentals of market dynamics, drivers of success and sustainable competitive position – the basics of future financial performance. Its aims are to:

- Quantify acquisition risks – customer, market, technology, competitor, regulatory, etc.

- Help understand the business, the business model, the industry, the competition, the management team and the regulatory environment

- Validate and assess the expected future performance of the business

- Help plan post-acquisition actions.

As a rule of thumb, CDD on market leaders and substantial businesses will focus more on market dynamics and regulation rather than customer satisfaction and competitive position. For example, many of the major private equity transactions, such as de-listing quoted companies, are about betting on a combination of market growth and the uplift achievable through newly motivated management. By contrast, CDD on niche businesses in smaller markets will pay less attention to market trends, but will often focus more on competitive position as this can be a greater determinant of future success.

The clear view of the company’s future provided by CDD should then be fed into the financial analysis and valuation. There is some positive overlap between CDD and financial due diligence (FDD); they come at the problem from different perspectives and the accountants are often relieved to rely on a more expert provider to cover the strategic and market angles. If the transaction involves a lot of debt, the lending bank will want to see the CDD as it knows that this is the key determinant of whether the business will have the cash flow to service the proposed debt level.

Who does commercial due diligence?

Commercial due diligence can be carried out internally or by an external organisation. Some frequent acquirers have built teams and developed a great of deal of in-house CDD expertise. If you have the resource, conducting CDD in-house saves money, builds expertise and avoids any loss of information between the CDD and the acquisition integration phase. However, this is the exception and most acquirers do not have sufficient employees with the right skills and experience to cope with the intense workload of an acquisition. Moreover, an in-house team cannot disguise its identity and will find it difficult to talk to market participants, especially competitors. The other problem with in-house CDD teams is ‘going native’, or not standing up to board level influencers and thus saying ‘yes’ to a bad deal. The situation can become impossibly uncomfortable for staff members if a senior director is on the warpath and wants to push his or her pet project through.

A range of external firms offer CDD services. The major audit firms have set out their stalls with some form of CDD offering, although the insightfulness of their results can be impeded by their fear of litigation. The mainstream management consultancies are perhaps too well qualified for the work and are often expensive. Other marketing consultancies can suffer from the inverse problem. Many acquirers therefore consider that they are best off using a specialist CDD consultancy.

What is the process and how does it work?

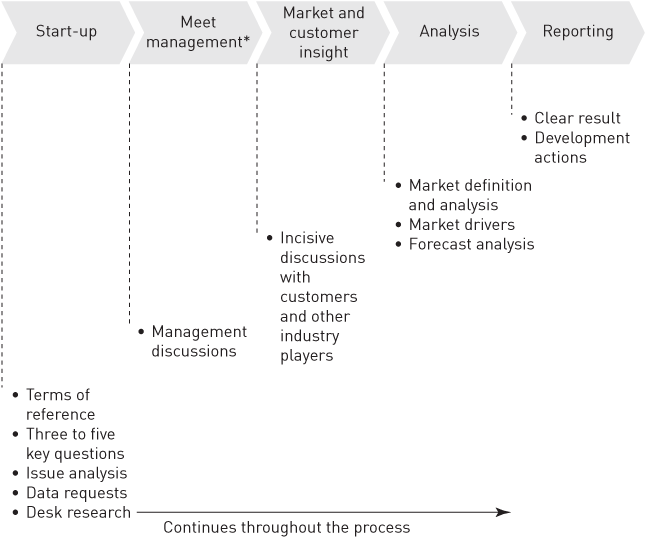

The commercial due diligence process is set out in Figure 6.2.

As can be seen, CDD is a five-stage process.

1. Start-up

The start-up phase is all about ensuring that everyone knows exactly what they are doing. A combination of time pressure and familiarity can lead the acquirer to tell advisers, ‘I want just the same as last time.’ This is an accident waiting to happen as no two acquisitions are the same, so they inevitably require different thinking. It may appear extravagant, but one UK private equity investor set best practice on a deal in the Netherlands by calling all of the acquisition team, with well over a dozen coming from the UK, to a meeting in Amsterdam. The sole purpose was to get everyone’s full attention, to finalise briefs and make sure that all efforts were joined up.

FIGURE 6.2 The commercial due diligence process

Note: * Where possible and typically when working alone

Terms of reference

Like all due diligence, CDD should not be conducted in a vacuum. As mentioned in Chapter 4, the CDD team must be aware of the full circumstances of the deal, why it is being done, how the target fits with the buyer’s strategy and what the buyer intends to do with it once the deal is done. Only then can the CDD team do its job properly and add value. CDD is essentially a mini-strategy review of the business you are buying.

As with any strategy review it is counter-productive to attempt to ‘boil the ocean’. Inevitably, there is a small number of issues critical to the target’s future. Given the time pressure and the inevitable desire to keep costs under control (although CDD is the least expensive of the main due diligence streams) it is essential to prioritise efforts on areas of uncertainty, risk and uplift.

EXAMPLES OF SPECIFIC QUESTIONS

Uncertainty

- The market has been growing, although the underlying trends have become unfavourable. Is the market about to turn down or is the business in a secure niche with a long-term positive outlook?

- The market appears to be set to accept this technology and take off, but will buyers commit now having already hesitated for a number of years?

- The target has a subsidiary in an unrelated business area which we would like to dispose of, but we do not know how marketable it is and we cannot afford to be left with an unattractive, unsalable asset. How attractive would this unit be to potential suitors on its own?

- The business is more profitable than all of its competitors, yet it has no obvious structural reason to be so. What is the reason for this and how can we be sure that this is sustainable?

- Much of the success of the business depends on the launch of a new version of its most important product. Will the product launch achieve what management claim?

Upside

- The business is less profitable than its competitors; we plan to improve margins, but is this achievable?

- The US market is ripe for exploitation and it will just take a national distribution deal to achieve penetration. How realistic is this?

Issue analysis

There are two basic approaches to problem solving as shown in Figure 6.3.

In simple terms, issue analysis involves setting out a logic tree for the factors that underpin the core question so that the work follows a structured, analytic approach. That core question might be as simple as ‘Should we buy the company?’, but it is better for it to be more specific, as in some of the examples above.

An example issue analysis is shown Figure 6.4. This is for a US niche manufacturing business, supplying cable and wire solutions. The buyer had worked out that the challenges facing the business were increasing the existing rate of growth and avoiding the commoditisation that afflicts similar markets. All of the questions are designed to provide insight into the key question.

FIGURE 6.3 The two basic approaches to problem solving

A full workplan can then flow out of the issue analysis. A task list is set up, each task being designed to answer one or more questions. The tasks are allocated to team members for execution.

Data requests

Business analysis requires data. Depending on the business and how the process is being run, the amount of data available on the business will vary from about enough to voluminous. A well-prepared company, often advised by an investment bank, will have gathered operating and financial data on the business. This is typically assembled in an electronic data room. In some cases the seller may even have hired consultants to go further than this and commissioned what is called vendor due diligence.

Inevitably the buyer and its advisers will require further operating data for its CDD assessment. Do not fall into the trap of requesting absolutely everything that you can think of that might be useful. It will not all be available, the request will annoy management and you will not use it all. The trick is to refer back to the key questions and to the issue analysis which you have prepared. You can then specifically request the data that help to crack open your understanding of the business.

CHECKLIST 6.1 Data request aimed at management

The CDD team should ask management to share relevant market information which the company holds. This checklist is simply a guide. The actual request should be in line with the key questions and the issue analysis.

Market

- Market reports/sources of market data

- Trade magazines/websites

- Trade show catalogues/websites

- Trade associations and contacts

Customers

- Customer data for past three years by account, by:

- revenue

- product mix

- Any customer surveys

- Customer lists for interviews

Other

- Strategic plan

- Development papers

- Organisation chart, especially sales and distribution

- Key industry contacts (associations, suppliers, regulators, etc.)

- Operating data and key performance indicators (e.g. utilisation rates, occupancy data)

The target’s business or strategic plan is a key document for the acquirer to obtain and assess. It is the job of the CDD team to validate these projections and the assumptions which lie behind them. Often the forecasts may have been re-worked and re-presented by the seller’s corporate finance house, in an information memorandum (IM). An IM is a sales document which inevitably presents the business in the best possible light. Watch out for unsubstantiated claims, financials that cover a limited time period, 3D graphics and graphs exaggerated by not beginning at zero. It is also worth working out if the plans were drawn up by management, or if they were foisted on them by advisers.

Management should be able to provide performance measures on the business. Key performance indicators (KPIs) are hard measures, although not typically based on financial information. As with any other analytical input, you need to check which measures really are relevant.

Examples of KPIs include:

- Hotel occupancy rates

- Production ‘up time’

- Product reject rate

- Consultant/service employee utilisation ratios

- Sales conversion ratios

- Average revenue per customer

- Customer retention rates

- Advertising page yield.

Whilst an internal analysis of the KPIs across a division or from one year to another is useful, the real value comes from competitor benchmarking. This requires careful planning and advanced interviewing skills to ensure that the information obtained from competitors can be used for valid comparisons. At this point it is possible to assess if certain performance levels or trends are the exception or industry-wide.

Desk research

With huge amounts of data now available to people sitting at their computers, the emphasis has moved from getting enough information to sorting it for relevance. Desk researchers often pick up interesting and useful information. But they also often fall into various traps. These can be finding interesting information that is not relevant to the questions in hand, or finding information that is flawed. The first is a red herring, the second is misleading. To avoid poor analysis – garbage in, garbage out – you need to develop a desk research strategy.

Many secondary sources have their limitations. They cover large, mass markets fairly well, but refer to niches only in passing. They are rarely completely up-to-date. It is tempting to take their growth forecasts as gospel, which is dangerous. Looking back they are often wrong and they do not often capture the subtleties of different market segments. Therefore, in addition to desk research, do not forget that getting onto the phone or out of the office can be very valuable.

BASICS FOR DESIGNING DESK RESEARCH STRATEGIES

- Use the issue analysis to determine what you are looking for through a structured work plan.

- Integrate desk research with the overall research and analysis.

- Do not just go to the usual sources; ask around to see which sources are most relevant to the market in question.

- Constantly challenge the integrity of the data gathered:

- Is it relevant?

- How out of date is it?

- Are the sample size, definitions and periods appropriate?

- How credible is the source; in what way might it be biased (e.g. was it funded by a lobby or pressure group)?

- Be clear about how you are going to use the data sets when you get them.

2. Meet management

The meet management phase is both important and sensitive. Whilst it provides grounding for the subsequent work, it must be handled carefully.

Management discussions

It is best to meet the management of the target company at the start of the CDD programme. The aim of this meeting is to:

- Reassure them that the CDD team knows what it is doing, appreciates the sensitivities involved, and will not disrupt the business’s current commercial relationships. Think how apprehensive you would feel about a bunch of consultants interviewing your best customers even without the added risk that they might let slip that you are selling out.

- Obtain a thorough briefing on the business and the market.

- Sell the benefits of the work; management should benefit from this mini-strategy review of their business. There can also be a PR spin-off with customers.

- Agree which key managers the CDD team can talk to. They will obviously be insiders to the deal.

- Outline the data request and explain why the data are needed.

- Agree the best way for the CDD team to approach customers and other industry contacts; obtain those customer details.

- Open channels of communication so that important topics can be discussed or validated as the work proceeds.

This is a very sensitive time for management. There is a lot at stake including their livelihoods; for owner-managers this is probably their retirement plan. On top of this is the inherent stress and disruption of the due diligence process itself; invariably management underestimates just how invasive the whole due diligence process can be. As these management meetings can be delicate, it is best to take experienced people. The last thing the buyer wants is a call from the vendor explaining that some bright young consultants have rubbed the management team up the wrong way. If the CDD team, or any other adviser for that matter, fails to build a positive relationship at this point it will struggle to do its work effectively.

3. Market and customer insight

The market and customer insight phase is the core of CDD. This allows the acquirer to get to grips with the commercial reality of the business, going far beyond all the presentations on the business that the acquirer will inevitably have been shown.

Customer assessment

Customers pay the bills. Working out if this is going to continue is a critical part of any CDD programme. As an antidote to the inevitable spiel from the seller about happy customers, the buyer has a range of tools available to assess continuing customer loyalty and spend. These include:

- In-depth, qualitative customer interviews

- Less-detailed, quantitative interviews

- Focus groups

- Internet surveys

- Analysis of customer data.

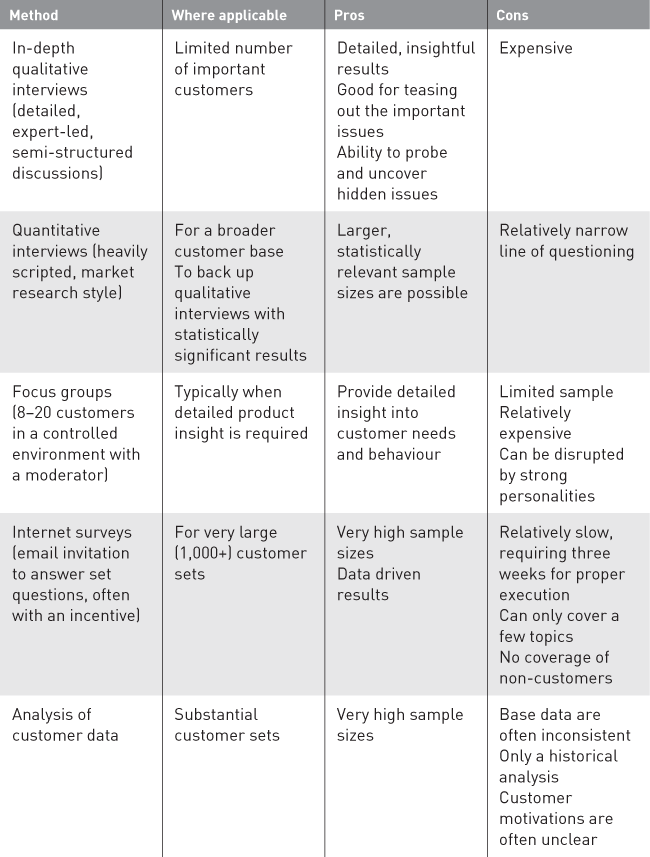

It’s horses for courses; Table 6.2 gives an idea of when each method works best.

These methods can be combined. For example, internet surveys are best prepared and backed up with a brief programme of in-depth qualitative interviews.

The CDD team should determine the sample set of customers to interview, although it is to some extent reliant on management to advise which interviewees will yield the best information. Management should also provide the contact details. Beware managers who are tempted to hand pick customers while keeping the CDD team away from problem cases.

Internet surveys are increasingly powerful, if well executed. They have the advantage of covering the entire customer database. However they do not cover prospective customers whilst former or unhappy customers are unlikely to respond.

Checklist 6.2 sets out a basic list of the topics which it can be useful to analyse, depending on the specifics of the business and the acquisition.

CHECKLIST 6.2 Potential topics for customer analysis

- Customer segmentation:

- Customer type

- Buying behaviour

- Purchasing analysis and historic trends, by customer segment:

- Average revenue per customer

- Customer retention/churn

- Basket of products or services bought

- Frequency of purchase

- Lifetime value

- Sales route/channel

- Source of new customer acquisition

- Differences between new, repeat and lapsed customers

- Customer satisfaction:

- Rating by key purchase criteria (e.g. price, quality, delivery, etc.)

- Net promoter score

Much of this analysis will allow the acquirer to see customer trends and draw conclusions about how the revenue mix is changing and how customer behaviour is evolving. It is worth focusing on one essential part of the customer picture, which is customer segmentation, and then seeing how this can link through the overall analysis.

Customer segmentation and key purchase criteria

Customers evaluate suppliers before purchasing, but it is not always clear to suppliers what their customers’ key purchasing criteria are; they just see that a sale has been made. Customer requirements may also vary from one market segment to another and even from customer to customer. This underlines the importance of segmenting the market accurately, as well as understanding precise customer needs.

EXAMPLE Removal firms

Table 6.3 shows that some customers of removal firms think mainly about price and if the odd book or piece of cutlery is lost or damaged that is less important than the money saved. For other customers the critical thing is that every possession arrives intact and price is a lesser concern. For others again, the process of moving is so stressful that the most important part of the service is simply the quality of service – the courtesy and the apparent concern for a smooth operation.

TABLE 6.3 Different key purchase criteria amongst customers of removals firms

| Customer type | Key purchase criterion |

| Price driven | Lowest price |

| Possession driven | Avoidance of damage or loss |

| Stress driven | Evident concern and consideration |

Critical success factors

Critical success factors (CSFs) define what a company must get right to achieve its goals and fulfil its strategy. The CSFs for a sports car company would include R&D, engineering excellence and branding. These deliver the performance and reputation required by the customer. Similarly the CSFs for the family car company would include wide distribution, quality management and marketing in order to deliver price, reliability and resale value.

Table 6.4 shows the links between key purchase criteria and critical success factors, and how they then can be measured by key performance indicators (KPIs).

Maintaining confidentiality while gaining customer insight

Obviously the CDD team cannot announce the real reason for its customer interviews to people outside the business: therefore it needs to agree the basis on which interviews are conducted with management. Typically the best approach is for the target to agree that the CDD team can say it is conducting a strategic review or customer care programme on behalf of the company and the management team. This platform requires the full cooperation of the target’s management and it must fit in with the company’s customer relationship programme. One target once refused to go along with a customer care platform with the curious boast that it never carries out customer surveys and its customers would know that. As might be expected with such an enlightened target company involved, that particular deal did not go ahead.

If customers are to be interviewed on behalf of the target company, customer-facing staff should be made aware of the research programme otherwise there can be embarrassment and confusion.

Management may offer to hand over existing customer surveys. Few companies conduct customer care surveys which approach the level of professionalism and detail of a well-run CDD programme. Consequently prior surveys are invariably no more useful than background reading.

The vendor, or the financial adviser running the transaction, may attempt to limit the customer research. Whilst protecting confidentiality and customer relationships is fine, it is not acceptable to prevent the acquirer from talking on a confidential or neutral basis to the people who know the real strengths and weaknesses of the company. Overly restricting access is usually counter-productive. The buyer speculates about what the seller has to hide and, if necessary, a skilled CDD team can get at least some customer reaction through undisclosed market research interviews.

Other market participants

We have already covered desk research and customer insight in this chapter. We will now look at some other primary sources, as set out in Figure 6.5.

Depending on the questions that you need to answer to really understand the value of the proposed acquisition, interviews beyond the customer set can be very valuable. These can include interviews with distributors, regulators, competitors, industry observers and other relevant contacts in the market. Even in very well-documented industries, such as telecoms and financial services, these interviews remain important. The industry’s reputable published statistical reports should be exploited to the full, but it is not possible to segment the market properly or analyse key drivers without speaking to relevant market participants.

Distributors, wholesalers, re-sellers, retailers or whoever else sells the product can be almost as important as the end customers themselves. In some markets these channels or distributors are in fact the company’s direct customers. They are almost inevitably better-informed than the end users about the detailed workings of the target company and the strengths and weaknesses of its products.

Sometimes the relationship between principal and distributor is not straightforward. For example, a leading French financial services company sold half its products through one nationally organised distributor. Enquiries revealed that this distributor strongly objected to certain conditions of its seven-year contract with the principal. These conditions had been acceptable at the start of the contract period, but had been made obsolete by changes in the industry. The principal obstinately refused to amend the terms of the contract and the distributor was actively planning to move on once the contract came to an end in less than a year’s time. This would wipe out half of the principal’s sales.

FIGURE 6.5 Primary information sources

Specifiers can be as influential as customers and distributors in certain markets. If an architect has specified a product or ‘equivalent’ then there is a strong chance that the builder will use it. Doctors are specifiers of pharmaceuticals and care homes. IT consultants specify computer hardware and software. Teachers specify school books.

Regulators can have a profound impact on industries, often in ways which are quite unforeseen. When the UK government started to encourage employees to make personal arrangements for their pensions it did not expect the pensions industry to adopt the forcible selling techniques which have given its sector a bad name. Regulators can spot and break up cartels, as for example in the UK where copper tube prices were fixed for a decade. An unwitting buyer of one of those manufacturers could subsequently find itself in court with one or more builders’ merchants claiming they are out of pocket.

Below are some examples of CDD programmes where regulatory change was a key consideration:

- The target company was launching an alternative directory enquiries service in various European countries. Deregulation of directory enquiries across Europe was opening up opportunities for new service providers, but delays in implementation and the ability of incumbents to slow liberalisation was impeding their entry. In such cases, new entrants only recoup their substantial set-up costs slowly and their well-worked business plans are rendered invalid.

- The target company manufactured a particular kind of safe. The UK regulations require this kind of safe to withstand attack by a thermal lance for a period of 15 seconds. The equivalent German regulations require that it withstand the attentions of a tank! As with many industries, the European Commission had the unenviable task of ‘harmonising’ these very different requirements, and in CDD it was important to ascertain the likely direction of future legislation. By talking to the relevant EC Directorate as well as numerous well-informed industry sources it became clear that the more rigorous German standards would not be imposed across the board.

- The target company made spare parts for lorries. The parts were ‘generic’, in that they met the same technical and performance specifications as the original parts, but they were not made or badged by the original equipment maker (OEM). An important part of the rationale for the deal was the possibility of exporting the company’s products to other European countries, and this meant understanding the current and likely future attitude of continental European regulators towards such ‘copy’ parts for vehicles.

Suppliers can be an excellent source of information, particularly when the supplier sees the acquisition target as a key account. If you want to buy a Ford dealership then it would be a good idea to find out what Ford thinks of the business and its prospects. If you are buying a cable maker – or any other capital intensive manufacturer – then it is worth interviewing the major equipment suppliers. They should know their target customers well. They may even be able to benchmark the target’s capex programme or manufacturing efficiency against its competitors. Suppliers are normally hungry for more information on their target markets and keen to identify new angles into customers, making them willing to talk to outsiders.

Competitors can be an excellent source of information; although most people think such interviews range from impossible to daunting. However, if they are approached in the right way competitors will usually be happy to talk about their rivals’ weaknesses to anyone who listens. An ideal question to slip into a conversation with a competitor might be: ‘So, given your comments, if you were running xyz (target company) what would you do?’ Expert interview networks such as Alphasights can provide access to competitors for a fee in those cases when their use is not banned by employers.

Former employees know the business intimately, but they are not always easy to include in the research programme. With social media such as LinkedIn, as well as expert networks, they are now fairly easy to find. Once identified, their opinions sometimes have to be discounted as they can have personal agendas, particularly if they left under difficult circumstances. But they can also be superb sources of information. For example, the customers of a market-leading instrumentation company unanimously agreed that the target company had the best products in its market, thanks to a first-class R&D department. Speaking to R&D people in the main competitor it was apparent that they were recent recruits from the target. It transpired that the target company’s management had emasculated the R&D department in order to improve the results of a disappointing year. The move was effective in the short term, but in the long term the company would clearly suffer from a lack of new products in an increasingly competitive market.

New entrants to a market will usually carry out a considerable amount of independent research before taking a market entry decision, so their views and plans are normally worth listening to. These companies can be hard to identify, although most market moves are advertised in some way; for example, in technical markets the research community will often get wind of potential developments.

Industry observers such as trade journalists and trade association officials, as well as academics and consultants, follow developments in their industries closely. Talking to them should provide a good introductory briefing to an industry and its challenges. They can also refer you to other useful contacts; the downside is that they can have their own agendas and constraints. Trade associations avoid being seen to promote the interests of one member firm above others, so they can help to describe some of the key characteristics of the industry as opposed to offering opinions about individual companies. Trade journalists are often talkative and are delighted to share their views with interested outsiders. Generally the more niche the industry, the more accessible and talkative they are.

Why should people talk?

There is a tremendous amount of information available to those who pick up the phone. Rather than being reticent, people generally talk much more than they should. But to get the best out of telephone interviews it helps to have the right approach. The secrets of success are set out in Checklist 6.3.

CHECKLIST 6.3 Conducting interviews with industry participants

- Use a referral or introduction, for example:

- ‘Company X (the target) has asked us to review its service levels and run a customer care programme.’

- ‘Fred at the trade association said that you are the best person to talk to about this.’

- ‘We have included (all the major industry players) in our survey and would not like your organisation to be left out.’

- Be pleasant, interesting and persuasive to charm the respondents into submission.

- Appeal to egos. When people with interesting jobs talk about their jobs they are in effect talking about themselves, often their favourite subject.

- Allow people to think. Respondents benefit from explaining a process or a situation to intelligent, encouraging listeners, as it forces them to get their own thoughts on the subject in order. They enjoy a conversation in which they are doing most of the talking, not because of rampant egomania, but because they are reviewing their own ideas as they go along.

- Give something in return. Experienced consultants can make some observations which even the most experienced (and most cynical) market participant will find valuable. Good CDD interviews are a two-way street, not simply a process of sucking information from unwitting victims.

DO PEOPLE TELL THE TRUTH?

As if doing CDD is not difficult enough already, the people contacted can sometimes mislead you. They rarely tell straightforward lies, but they often fail to tell the truth. Sometimes people:

- Do not remember, or they mis-remember certain important facts

- Mis-interpret or misunderstand the question and provide the answer to another question – for example they provide the market size for all apples as opposed to just green apples

- Never knew the detail in the first place, but would be embarrassed to appear less knowledgeable than they think they should be and so they provide a well intentioned, but misleading, answer

- Withhold information because they are uncertain how it will be used.

Experienced interviewers think on their feet and spot erroneous or incoherent information and then find a sympathetic way in which to challenge it.

4. Analysis

The analysis phase brings together all of the various elements. It provides the insight that the acquirer needs to make an informed decision on the deal. CDD has strong similarities to a corporate strategy review or the type of strategic marketing review which would be carried out prior to launching a new product Therefore it uses a number of the techniques and tools used in such reviews.

Market analysis

The key questions that shape the CDD will inevitably include market analysis. To various extents, all businesses are victims of their markets or, in the words of Warren Buffett, ‘when a management with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for bad economics, it is the reputation of the business that remains intact.’

There is a lot more to market analysis than buying the latest industry report. There are three essentials to get right:

- Define the market accurately.

- Do relevant analysis with valid data.

- Work out what makes that market tick.

Market definition and analysis

Incorrect market definition is a regular pitfall. Do we really know what business the target company is in? Have we actually defined the market, or market segment, correctly? Whilst published reports on markets can be helpful, they can also be misleading as readers can be snared into using a broader definition than the niche in which the business operates.

Equally, when seeking out market information, do we know what the business model is? It is not always clear what the business is, sometimes intentionally. The job of CDD is to see through this and provide clarity by answering the following questions:

- Is there more than one business model?

- Which parts make money – where do the profits come from?

- Where is the business positioned in the value chain?

- What has driven historic growth?

- What are the critical success factors for a business of this kind?

- Which parts of the business are core and which non-core?

- Who are the real competitors for each element of the business?

- A helicopter company in Hawaii may not be in the transportation business – it may be a high-end tourist attraction.

- When AT&T acquired NCR, it thought that it was buying an IT business – in fact it got what was inscribed on the machines: National Cash Register.

- We can all describe the differences between a British Airways, Virgin Atlantic, easyJet and Ryanair flight. These companies have different approaches to making money: BA is all about filling the premium cabins with inter-lining through its London hub; Ryanair is all about volume, low-advertised price with add-ons, and regional airports.

Business models and cultures

Do not forget that a company’s business model will reflect its culture, and vice versa. Culturally you cannot just swap the employees of the various airlines; each would only get more complaints! Charging customers for not printing their own boarding passes is a very different skill to handing out champagne in first class. This is why proper business model analysis, including the softer cultural side, is an essential first step in ensuring that integration actions do not damage the business.

Let us take the helicopter company example further. It provides joy rides for wealthy tourists in Hawaii. The market is best defined by who its customers are and the situation in which they find themselves. This leads us to looking at the adventure activity and attraction markets, with a specific focus on activities that might cost $1,000. If a market report has been published on these markets it is highly unlikely to have segmented out the high net worth individual segment, let alone the helicopter ride portion. In its simplest form, the market analysis will address the following questions:

- What is the volume of tourists coming to Hawaii?

- What proportion is capable of spending $1,000 on an activity?

- Of these, how many may be inclined to take a helicopter ride?

In the absence of perfect market data we may need to use proxies and estimates for the analysis. In this case, the tourist authorities have good data for the first step that quantifies tourist numbers. But for the later, more detailed steps, we will have to be more imaginative. For example we may define high net worth individuals as those who can spend over $250 per night on accommodation, for which data are readily available. We also know that first-time tourists are the most likely to take helicopter rides, so we can introduce that cut into the subsequent analysis.

That is the supply side. Then on the demand side we need to ask questions like:

- How many helicopters are available to provide joy rides?

- Are they restricted by any form of regulation such as fly-over rights or landing spots?

- How busy are they? And so on.

As we saw with the Hawaiian helicopter example, each case requires specific market analyses in line with the key questions. Checklist 6.4 sets out a basic list of market analysis topics. Of course there is no need to conduct each of these analyses by rote; the trick is to select those that are relevant.

CHECKLIST 6.4 Potential topics for market analysis

- Market definition

- Market segmentation, for example:

- Products or services

- Customer groups

- Competitors

- Market growth, by segment

- Drivers of market growth (both positive and negative)

- Sales or distribution structure

- Industry value chain

- Business model comparison

- Critical success factors

- Market attractiveness, for example:

- Degree of market rivalry

- Ease of substitution

- Barriers to entry

- Profit pool analysis

Market drivers

Once we have defined the market, we need to know what makes it tick. In other words, what drives the market?

Continuing with the helicopter ride company, our market analysis might have done a great job working out how many high-end tourists with a taste for adventure or joy rides are expected go to Hawaii in the future but that is only part of the story. We now need to isolate the factors that will cause more, or fewer, of these people to come to Hawaii. On the demand side, drivers might include the future levels of premium accommodation or the number of cruise liners arriving from Japan.

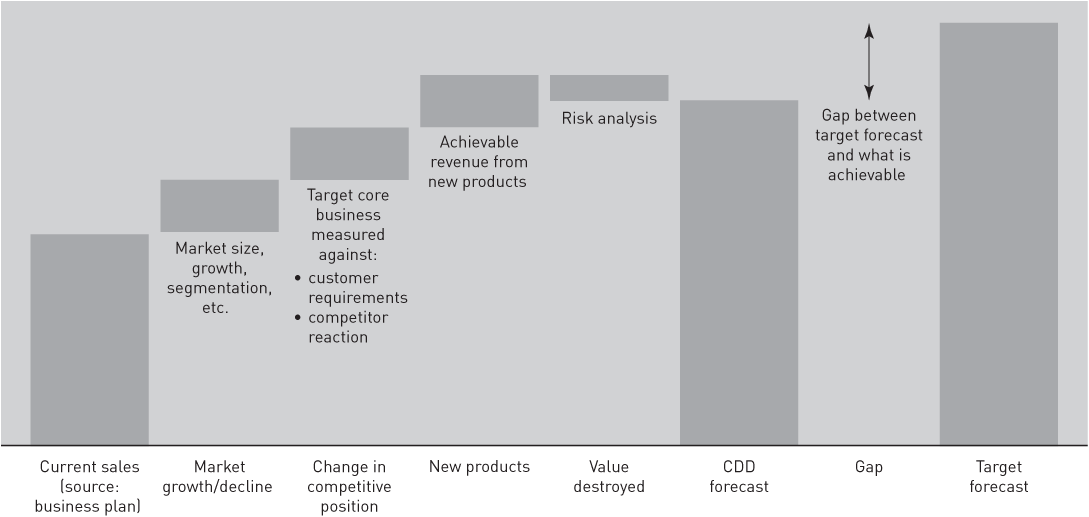

Forecast analysis

A critical element of CDD is to provide a clear opinion on the target company’s forecasts and their achievability. The simple way to analyse forecasts is to establish growth in the relevant market segments and then to review the variance between the target’s forecast growth rate and that of the market. Plenty of companies claim to serve markets which are growing at 3–4 per cent per annum, yet their sales forecast is for 6–8 per cent per annum. This means that the company is gaining market share. Before buying the business, you must work out if it really is capable of gaining share and who in particular is losing share. This is where a critical success factor (CSF) analysis can be a useful way to bridge any gaps. If the business can be proven to have an above-average performance against CSFs for the industry, then it can be expected to outperform the market. Conversely if it is below average on its CSF performance then any claim to out-perform the market is difficult to believe.

The logical approach is for the CDD to produce its own forecast of the various profit streams based on customer and market data then compare this with the target company’s forecast. The process is represented in Figure 6.6.

5. Reporting

At the end of a commercial due diligence exercise you will get a report. Insist on a presentation because words on a page never tell the whole story. Besides, a due diligence report, based on the same facts, can sound optimistic or pessimistic depending on the author.

Clear result

The reporting topics and style differ according to the transaction, who is doing the work and, most importantly, the audience. Commercial due diligence exercises are allowed three to four weeks – and often less. Because time is short, it is essential to focus on the critical issues which means concentrating on the areas at greatest risk.

The vendor will not be privy to the report in the first instance. However as part of the negotiations the buyer may choose to release part or even all the report to the vendor as a tactic to prove that the business has less value than originally thought.

Table 6.5 shows a CDD report format which has stood the test of time and has proved highly satisfactory for a wide variety of acquirers and investors.

TABLE 6.5 A CDD report format

| Report section | Explanation |

| Contents | |

| Terms of reference | The brief, including the key questions, and the methodology followed |

| Background | Basic data on the business which sets the scene for the various readers of the report |

| The answer on a page | A single page of bullet points, summarising all of the key issues in a logical order |

| Conclusions | Conclusions for each of the individual markets, business units and revenue streams analysed |

| Executive summary (optional) | A formal written explanation of the ‘answer’ and conclusions |

| Analysis | Structured analysis of each of the key issues which were set out in the issue analysis and which have culminated in the conclusions. These might be grouped by market, competitive position and future prospects. The analysis should be based on factual information: when facts are not available, opinions should be used, so long as they can be substantiated |

| Supporting data | Additional market data, profiles of key players in the market |

| Appendices | Background explanatory material about the company, its industry and customers |

Conclusion on commercial due diligence

Commercial due diligence is the process of investigating a company and its markets. It employs a mix of information from the target company and secondary sources including published market information, but it also relies heavily on primary sources – customers, competitors and other market participants. The key skills required include the ability to analyse the industry, the ability to conduct external interviews effectively, and the ability to tie all the information to the company’s competitive position and to its business plan. CDD is one of the most powerful ways to reduce the risk in a transaction; it should also help you negotiate the best deal, and plan post-acquisition integration actions.

As already noted, there is usually a close relationship between commercial and financial due diligence. Indeed it may sometimes appear that a financial due diligence (FDD) report covers most of the commercial issues. In fact commercial and financial due diligence are quite different processes, although they do indeed seek to answer some of the same questions. The critical difference is that a CDD investigation is based primarily on information available outside the target company, while a FDD investigation is based primarily on documents obtained from the target and on interviews with its management. The commercial and financial investigations therefore complement each other in arriving at the ultimate goal, which is a view on the likely future performance of the target business.

Why carry out both CDD and FDD?

In short because you will get a different perspective. Remember what we said earlier. Due diligence is not just about confirming assets and rooting out hidden liabilities. The success of a deal is going to rely on the target’s performance in the market and CDD is one of the few due diligence disciplines that gets its information from that market.

FDD teams focus internally. They analyse the financial records and speak at length with the company’s management. After some contact with management, CDD usually starts with secondary sources (i.e. desk research) and carries on to use primary sources, i.e. enquiries among people who are actively involved in the market, or who observe it closely such as customers, distributors, specifiers, regulators, suppliers, competitors and former employees.

CDD and FDD should be seen as complementary activities, both looking to understand the target’s sustainable profit from different angles: CDD from an external perspective focusing on the future and FDD using historic information held internally (see Figure 6.7).

The two work programmes should be co-ordinated and culminate in jointly agreed forecasts. The two teams should communicate freely with each other because their different perspectives can open up new lines of enquiry and because each has access to information which can be valuable to the other. For example, the FDD team may have easy access to lists of former customers and perhaps former employees. The CDD team could obtain this information itself, but it would take longer. Similarly, the CDD team can obtain a more precise view of market size, segmentation and future growth rates than accountants; the FDD team can plug this information into its forecasts and scenarios.

Financial investigations

What are the key issues to be covered?

Financial due diligence is not an audit. FDD should at all times be focused on the future. It frequently draws on historical information, but examining past events is useful only if it provides an insight into the future. Thus FDD is about identifying the target company’s maintainable earnings and assessing the degree of risk attached to them.

The key financial issues covered by FDD are usually:

- Earnings

- Assets

- Liabilities

- Cash flows

- Net cash or debt, and

- Management.

Earnings

FDD should assess the level of maintainable earnings of the target business because it usually provides a guide to the future performance of the business. This requires a thorough understanding of the entire business and its market: it is much more than the identification and stripping-out of non-recurring profit and loss items.

Assets

FDD should review the business’s assets. Again, this work will have an eye on the future – it will look at accounting issues, but it should be mostly concerned with the nature of the assets, and their suitability for the business. Cash flow is going to suffer if assets are reaching the end of their life and will need replacing soon after the business is acquired. FDD can also identify any assets the business owns, but does not necessarily need.

The investigation can also compare the market value of assets with their net book value. For example, low net book values may give a misleading view of the level of capital required by the business over the long term, and so may flatter the true maintainable earnings of the business. FDD should consider asset ownership; a sale and leaseback transaction may be an efficient way to release cash, indirectly helping to finance the acquisition itself.

Liabilities

The investigation of liabilities should look for any liabilities which have not been disclosed, or whose value has been underestimated. This part of the investigation tends to be more backward-looking: but, of course, the key underlying objective is to spot any unexpected future costs. Under-funded pension liabilities would be an obvious example.

Cash flows

To what extent are profits not reflected as net cash inflows? There may be good reasons for a business not to generate cash – the business may have invested heavily, or a business may be growing rapidly with the increased working capital requirement draining cash. These are important issues for any new owner of a business who may have to find extra cash to finance it properly.

Net cash or debt

Businesses are typically valued free of cash or debt; if either is in the company, this may impact on the transaction price. Assessing the level of cash or debt is not always easy. If the business is very seasonal – such as tourism or retail – or if some financial debt instruments are accounted for off balance sheet then the calculations are harder.

Management

An FDD team will have a lot of contact, discussion and interviews with the target’s management. Consequently a commercially minded FDD team should be well placed to comment on the strengths, weaknesses and even organisation of the management team. Experienced acquirers ask for these opinions as they are keen to anticipate how the target’s management team will fit into the new environment of the combined businesses.

Where does the information come from?

The investigating accountant will obtain information from a wide variety of sources, but almost always the sources of information will be inside the target company.

Shopping lists

It is common practice to provide the vendors and their advisers with a detailed information request list (or ‘shopping list’). FDD advisers have standard lists. The experienced ones know that it is best to tailor them to the circumstances of each particular transaction. Too many due diligence investigations get off to a bad start because the various advisers inundate the unsuspecting vendors with huge ill-considered requests for information, with considerable duplication across the different lists. Understandably, the vendors take this badly. Then, either because they are genuinely annoyed or for tactical reasons, they may exploit this poor preparation to put the purchaser on the back foot, trying to weaken his negotiating position.

Appendix A provides an example of a shortened FDD information request list.

Interviews with the target’s management

Interviews form a critical part of most financial investigations. They will often be based around documents, but the investigating accountant will also steer the conversation away from hard issues, always seeking to improve his or her understanding of the target business, its strengths and weaknesses, what it can achieve and where it might prove vulnerable. Covering similar ground with several different members of the target’s management team can be enlightening; for example, comparing the views of the managing director, finance director and production director.

As the sale of a business is often a traumatic period filled with uncertainty for its managers, the investigating accountant must be sensitive to the different circumstances of each transaction and each manager’s agenda. A newly-recruited manager may have little ‘baggage’ and be more ready to criticise the business while a long-standing manager has valuable, detailed knowledge but may be less objective and feel that any criticism of the business amounts to a personal criticism.

An owner manager, who has spent his life building his or her business, will naturally tend to present the business in a favourable light. The prospects of a professional manager who is not a vendor and who is being ‘sold with the business’ are quite different; he or she may quite quickly ‘change sides’ and identify with the purchaser, the prospective employer. He or she may even be motivated to show the business in a poor light, so that good performance following the acquisition is attributed to the manager’s subsequent good management.

The target’s historical advisers

It is common practice for the investigating accountants to review the working papers of the target’s auditors and to interview the auditors. This is for two reasons: