The integration plan

Introduction

It is no accident that this chapter comes where it does in this book. You must start thinking about integration the second you start getting serious about an acquisition. It is not something which should be left until the ink dries on the deal documentation. However well the strategy has been worked out and however well the deal has been transacted, no acquisition is ever going to be successful if there is no plan for the aftermath – or if that plan is not properly executed. This may sound perfectly obvious, but poor integration is the single biggest reason for acquisitions to fail and the reason integration is so poorly carried out is that it gets forgotten. In addition, while much attention is paid to the legal, financial and operational elements of acquisitions it has become increasingly apparent that the management of the human side of change is the real key to maximising the value of a deal.

The golden rules of acquisition integration

There are five golden rules for acquisition integration:

- Plan early. Acquisition integration should begin before due diligence and continue through the pre-deal process.

- Move quickly once the deal is done.

- Minimise uncertainty.

- Manage properly. Integration management is a full-time job.

- Soft issues are paramount and far more important than driving out the cost savings.

We will consider each of these in turn before going on to look at the integration plan and its execution.

1. Plan early

There are three reasons for planning integration at the earliest stage possible:

- If you have no clear idea of where and how you are going to find extra value it is impossible to work out how much the business is worth to you.

- Post-deal integration is vital to success and one of the best ways of collecting the information needed for integration planning is through due diligence. Integration issues should be identified during due diligence, just as legal or accounting issues would be.

- Speed is very important in integration. Early planning means that integration can proceed at full speed on day one leading to early victories that demonstrate progress.

The link between integration, valuation and due diligence

The cash flows of the combined businesses will depend on how they are run. Integration planning therefore has a direct input into valuation and, as already mentioned, the due diligence phase should include critical testing and challenging of the estimated synergies. These are often misjudged. Figure 5.1 shows the relationship between integration, valuation and due diligence.

Post-acquisition planning should address the most important issues which impact on valuation. The most important of these are where the synergy benefits are going to come from and how (and when) they are going to be realised.

Private equity investors develop detailed business plans with their management teams, which are effectively integration plans, before a deal is completed. All acquirers should do the same by developing an objective explanation of how the deal contributes to the acquiring company’s strategy. This in turn will set the agenda for integration.

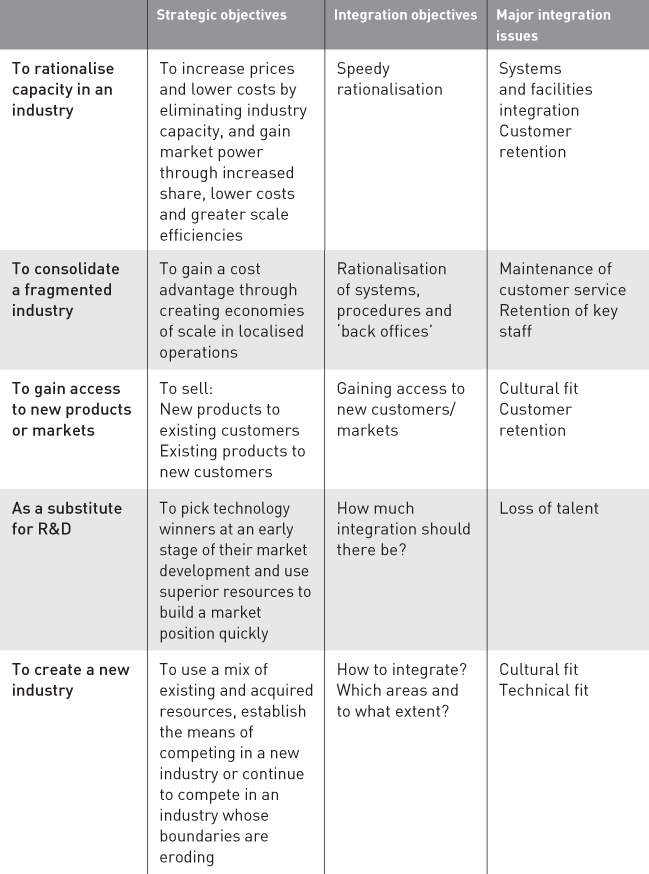

The main reasons for acquiring were shown in Table 2.1, which has been expanded into Table 5.1. As can be seen, there are only five.

FIGURE 5.1 The relationship between valuation, due diligence and the integration plan

As shown in Table 5.1, being crystal-clear on the acquisition rationale and on what the acquisition is supposed to achieve – what are we buying and why – will help define the broad framework for integration. Use due diligence to help fill in the details, and specifically to help:

- Confirm the sources of the post-deal competitive advantage and identify how to capture them.

- Quantify market growth – extent and timing and how to capture it.

- Define how closely the acquiring company can integrate the target company into its existing operations.

- Identify major cultural, structural or legal factors which influence the speed and direction of integration.

- Identify the operational demands of integration:

- Provide a clear project plan for management, with associated tasks, resource requirements, timelines and milestones.

Table 5.1 is an ideal. Often there are operational and cultural barriers to integration which need to be identified.

Operational barriers to integration

Some significant operational barriers to integration are set out in Table 5.2.

TABLE 5.2 Operational barriers to acquisition integration

| Barrier | Comment |

| Level of physical separation | Where the target company operates in a distant country or region it may be wise to maintain a higher than normal level of operational independence |

| Structure of distribution channels | Where a target company is successfully serving customers through separate distribution channels it is probably sensible to maintain these independent channels, at least in the first instance |

| Type of technology | If the target’s technology is different to that of its new company there is a strong argument for allowing at least the core technical team to have some autonomy |

| Type of operating systems | Similarly, where the operating systems (IT platforms) are complex, and incompatible with the parent company’s systems it may make sense to retain functional independence, at least in the short term. Obviously key reporting systems must be aligned |

| Demands of senior management and stakeholders | The deal structure (earn-out, minority stake, etc.) may require partial independence for an initial period. This should be factored into the negotiated price |

| Legal constraints | Legal constraints may require the parent company to operate at arm’s length within a particular market and maintain a high level of independence |

| Public relations considerations | There may be a public relations requirement in certain markets and certain sectors to retain the acquired brand and independent operating units; again this needs to be factored into the negotiated price |

Operational integration barriers can increase the risk and even become ‘deal-breakers’. It is a mistake to allow such operational barriers to pass largely unnoticed during negotiation, as they can become real problems later on.

Cultural barriers to integration

The culture of a company is the set of assumptions, beliefs and accepted rules of conduct that define the way things are done. These are never written down and most people in an organisation would be hard pressed to articulate just what the organisation’s culture is. However, these rules and shared beliefs are powerful. It is a mistake for an acquirer to assume that the target company will have anything like the same cultural dynamics as itself. Morrisons, a leading food retailer, blamed its post-acquisition performance dip on the culture clash with Safeway while Marks and Spencer took ten years to get to grips with Brooks Brothers’ culture. DaimlerChrysler provides another example of the problems that can arise from a culture clash among employees. The integration team invested much time and money trying to help employees understand the differences between American and German culture, but the firm’s real problems seemed to stem from differences in management perceptions and business practices. The firms championed different values, had different compensation structures, and ultimately, had very different philosophies about how to brand their products.

It is very important for acquirers to spend time on understanding the way in which the personnel within the target company behave – both individually and within the ‘culture’ of the business. Management can then decide how it would like to see the combined company’s culture develop and, in the meantime, adapt the way it manages the target. Table 5.3 summarises the main points to consider.

TABLE 5.3 Areas of cultural difference to be assessed

| Area | Difference to consider between acquirer and target |

| Structure | Is responsibility and authority very different? |

| Staff | Does it employ many more people to carry out similar tasks? |

| Skills | Does it have a lower emphasis on the importance of skills development within the organisation? |

| (Management) style | Is there a different emphasis on the way tasks are carried out (some typical broad divisions are bureaucratic, authoritarian and democratic)? |

| Shared values | Is there a common set of beliefs within the organisation as to how it should develop and what are they? |

| Systems | Does the target go about recruitment, appraisal, motivation, training and discipline in a very different way? |

| Reporting | How disciplined, formal and financial are reporting procedures? |

Information will have to be collected from various sources to understand what is important:

- Management interviews (if access is granted)

- Relevant experts if the acquisition is in a new country/sector

- Trade literature and website visits

- Ex-employees (through contacts and due diligence if possible)

- Customers (through contacts and due diligence if possible)

- Suppliers (through contacts and due diligence if possible)

- Mystery shopping (acting as a prospective customer and analysing responses).

It is also useful to remember that culture tends to reflect the business model, so it therefore makes sense to understand and reflect on differences between the two companies’ business models while assessing their cultures.

Cultural convergence is rarely achieved quickly and sometimes not at all. Moreover, acquired employees seem to have fewer problems with ‘they are very different from us’, than they have with ‘they are imposing their ways and did not listen to us’. Overemphasis on controlling newly acquired firms by imposing goals and decisions on them may lead to problems amongst the very group who may be instrumental in determining the acquisition’s ultimate success. Although people within an organisation learn to accept its working practices over time, we rarely have the luxury of several months or years with an acquisition. Changes need to be made quickly. This reinforces the need to concentrate only on essential changes and those which will have a significant impact in the short term.

Adjust integration to fit the cultural gap

If a target has a significantly different culture, this can substantially increase post-acquisition costs or hold back performance. The risk increases if the businesses are to be merged as opposed to operating as independent units.

The acquirer needs to assess the impact of the cultural divide and plan accordingly. Where there is a big cultural gap between the two organisations:

- The pace of many aspects of integration should be slowed down.

- The acquirer’s management may have to spend more time with the business.

- The level of integration may be revised down, at least for the first 6–12 months.

- The new parent should explain in detail why certain changes must be made and not just inflict them without consultation unless absolutely necessary.

- Company training levels may have to be enhanced.

- Various standardised operating procedures may need to be introduced and enforced.

- Additional financial resources may need to be budgeted for.

Operational and cultural constraints may mean choices have to be made about the way in which the target will be managed, ranging from allowing the target to have effective operating independence through partial integration to taking full control.

The acquirer should be clear about the type of parent it wants to be and the level of independence it will allow the acquired business. Table 5.4 shows the options.

TABLE 5.4 Level of integration options

For most acquisitions, the ideal is to achieve full integration, though the speed at which this is achieved may be influenced by particular circumstances. It took Reed International and Elsevier Science about five years to integrate properly into Reed Elsevier. Broadly, the less the target is integrated, the greater the level of risk. Risks include failure to achieve cost savings, and conflicts about strategic direction, investment and sales and marketing or other policies.

Thinking about the right arrangement cannot await closing. The integration team should use the information and time during the due diligence process to develop the appropriate integration approach and have in place the necessary action plans ready for execution on day one. Whilst taking control, acquirers should not forget that integration should be a two-way process. Acquirers are not perfect and acquired companies are not run by dummies. The best acquirers know that there may well be some tricks to learn from the business it is buying and that the integration policy and process must not be allowed to bury this value.

2. Move quickly once the deal is done

Before walking through the door of its new prized asset, the acquiring company must know how it is going to manage integration. Once inside the business, it must then put its plan into action. The reasons for speed are the:

- Need to reduce employees’ uncertainty quickly (see below)

- Advantage of capitalising on momentum; playing on the expectation of change

- Need to return managers to their original jobs

- Need to show results which quickly justify the acquisition.

Any factors that lessen the need for full speed should already have been analysed and their impact built in to the integration plan. In any acquisition, there are three areas requiring early attention:

- Ensuring that the acquirer gains complete financial control of the operation

- Communicating effectively with all the stakeholders of the acquired business

- Managing the expectations of all involved.

3. Minimise uncertainty

Change equals uncertainty. Any failure to communicate leaves employees uncertain about their futures, and it is often this uncertainty, rather than the changes themselves, that lead to dysfunctional outcomes such as stress, job dissatisfaction, and low trust in, and commitment to, the organisation. Uncertainty stems from the fact that the groups of people affected have a number of expectations but no idea of whether or not those expectations will be met. Their first concerns will be ‘me’ questions such as ‘What does this mean for me?’ For the acquirer this means:

- Agreeing the way forward with the sellers

- Making people decisions early

- Identifying key talent

- Communicating openly, honestly and a lot more than you think you have to.

Agree the way forward with the sellers

Consensus among buyers and sellers on the merged company’s strategy and operating principles significantly contributes to post-acquisition performance by minimising destructive conflicts, political behaviours and confusion among employees about lines of authority.

A high level of consensus is possible to achieve even when the two sides have a low level of cultural fit. Target company employees will be ready to accept the management styles imposed by the acquirer if they see the deal as an opportunity to advance their careers.

Make people decisions early

As the buyer you will have convinced yourself that you can run the business better and will be itching to get on with it. The first concern of those who you are going to rely on to make all those changes is: what does this mean for me? They all know that acquisitions mean job losses so where do you think their logic takes them? And having got there, is their next instinct to work productively and serve customers with a smile? People like certainty. Even if there are to be mass redundancies and closures it is best to say so up front and then quickly get them out of the way. Do not procrastinate; there is no ‘right’ time to make this sort of announcement. With it done, at least everyone knows where they stand. As long as restructuring is handled with sensitivity people will respond much better than they will to creeping, piecemeal changes that only add to the anxiety.

Identify key talent

Key people or groups are those whose departure would have a significant detrimental effect on the organisation. People or groups can be considered ‘key’ for various reasons, but the business impact of losing them should be the factor that deems them essential. The impact that their departure would have might include, for example, the loss of a key client or customer, important innovation abilities, knowledge of a core product or service offering, or considerable project-management skills. Once the key talent has been identified, the factors that are important to retain these people must be understood and an action plan developed that covers both the macro-level (organisation-wide human resources practices) and micro-level (manager-to-employee) engagement factors.

For example, at the macro, organisation-wide level, management might conclude that key talent needs to be fully aware of, and included in, the core human resources practices of the merged company. At the micro-level management might think in terms of increases in base and/or bonus compensation, better job titles, bigger offices, bigger roles and/or responsibilities, assignment to high-profile projects, changes of location, etc.

Communicate openly

In essence, you need to communicate openly. There should be no secrets, no surprises, no hype and no empty promises. This includes being able to say, ‘we don’t know’ or ‘we haven’t decided yet’.

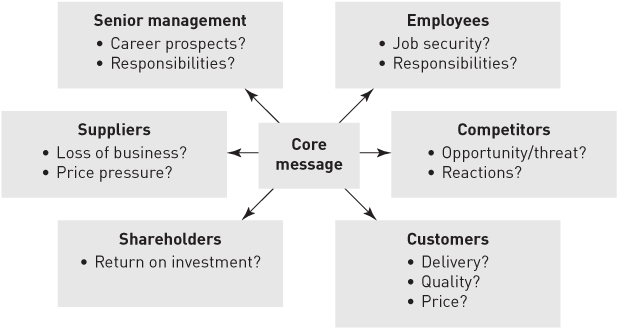

Whilst the acquirer may be pumping out a consistent message about how great the new world will be, this will by no means be what everyone will be thinking. Figure 5.2 outlines some stakeholders concerns.

This illustration shows that communication with stakeholders is complex. There must be a consistent core message. Underneath this, different messages are required for different audiences. Each one must be honest and accurate, but tailored to address the real concerns of real people.

Best practice in communication is to:

- Communicate early and often; avoid silence.

- Communicate in a coherent and consistent manner.

- Avoid contradictory messages; they destroy credibility and increase uncertainty.

- Appoint a single person or small team to act as the focal point for the communication.

- Develop specific messages to address the individual needs of each of the differing audiences.

- Use the best communication tools, language and tone for each audience.

- Listen to feedback; establish a two-way communication process.

- Answer questions as honestly as possible – if you don’t know, say so.

- Be open about reasons for the acquisition and the likelihood of job losses.

- Challenge false rumours.

Remember that actions and non-verbal signals are very important and that a physical presence is the best way of confirming the written message.

Worst practice is for the message to get out in the wrong way. One British group forgot about time zones. It prepared a press release with a time of release embargo for the morning, but because it did not specify GMT in the UK, employees in Asia heard about the acquisition on the radio on the way in to work. They immediately got on the phone to colleagues elsewhere in the world and the communication team had to back-pedal its way out of a mess.

Do not forget the customer

Uncertainty does not just exist internally. Customers have not necessarily been sitting around waiting for their supplier to be taken over. They are likely to react with scepticism and ask questions like ‘Will prices go up?’ and ‘Will delivery change?’ Do not forget that competitors will react by targeting accounts in the hope that events have unsettled them.

Do not forget the power of symbolism

Sometimes painting the canteen is enough. Positive progress does not have to be with the big things; in fact progress can be tricky with the bigger things because they take too long to realise.

Treating those who will suffer through restructuring with respect and maintaining their dignity also sends strong signals. This is a powerful way of showing what sort of company they are now working for.

4. Manage properly

The speed and effectiveness with which integration can be achieved is determined by the cultural compatibility of the combining organisations and the resultant cultural dynamics (see below), and the way in which the integration process is managed.

Integrating employees, products, services, operations, systems and processes can be daunting. For maximum efficiency and to avoid becoming bogged down, acquisition integration needs to be standardised, as far as possible, to include formalised and centralised integration management with a designated leader and team, and standard principles, tools, methods and processes both at departmental and corporate level. Above all, the deal’s primary sources of value need to be clear to all from the outset and set the priorities for integration. Finally, synergy targets should be included in the business unit’s budget.

Should we appoint an integration manager?

Yes, you should. Like any other big project you need one person to be accountable for the project’s success otherwise there will be delay, false starts and confusion. Integration is a full-time job. It cannot be done part-time by, say, the buyer’s MD or the MD of the relevant subsidiary. These people have a business to run and besides that they will concentrate on the urgent day-to-day issues. Nor should it be left to some bright MBA unless the integration is small and highly-structured. An integration manager needs to be a well-respected all-rounder who understands the industry, who knows his or her way round the acquiring company and who has the confidence of its senior management. Other skills and attributes will include:

- Proven experience in project management

- Effective interpersonal skills

- Sensitivity to cultural differences

- Ability to facilitate project groups.

Ideally, the integration manager will be in the midstream of his or her career, with a broad experience while remaining receptive to new and evolving business practices. He or she must have the authority to make decisions, co-ordinate taskforces and set the pace.

Effective integration requires clarity of purpose, detailed target setting and detailed reviews. Smaller acquisitions and private equity transactions require less integration than larger complex mergers, but even the smallest ‘stand-alone’ transactions require a plan. The integration should be structured around sources of value. It is also necessary to articulate non-financial aims such as a single financial reporting system or a single sales force.

Role of the integration manager

The MD, not the integration manager, is accountable for the performance of the business. The integration manager acts like a consultant held accountable for the creation and delivery of the integration plan and reaching its milestones. It is all too easy for people in an organisation to get caught up in the glamour of integration, but management must not get distracted. At least 90 per cent of the organisation should be focused on the day-to-day business.

The integration team

Acquisition integration is like any other major project. It has a one-off objective, limited duration, financial or other limitations, complexity and potential risk, and requires an inter-disciplinary approach. The integration team should therefore include members with both project-management experience and operational skills. If the required experience or skills are not available, the acquirer should consider bringing in external resources such as consultants or interim managers. Key managers must be selected as early as possible. They will then make decisions on additional assistance required during acquisition integration. The integration team should consist of a balance of different people and skills. At least some team members should have previous acquisition and integration experience.

As the probability of making the acquisition increases, the support provided to the acquisition team should increase. It is best to maintain continuity by adding additional team members to an existing structure. The level of additional resource required depends on the complexity of the acquisition, its strategic importance and its size. Experience suggests that in larger acquisitions, individuals should be assigned in at least six areas:

Each of these areas will have specific and detailed tasks which should be broken down in detail, and then built into the overall master plan. If this all sounds a bit much, remember that resource requirements are frequently underestimated. Integration teams need to understand the value for which they are accountable.

If outsiders are needed, they can be expensive, but remember always that their cost is insignificant in the context of an acquisition. The trade-off of more effective and more rapid integration against the cost of adding a few additional internal or external members to the team is often significant. Trying to muddle through with existing resources is short-sighted and often counter-productive.

Many executives fail to appreciate the scale of the merger task. Imagine bringing together two organisations that ostensibly mirror each other in size and function: two finance, marketing and research and development departments, two sets of manufacturing or retail sites, differing information technology and international operations. The numbers can be enormous: the aborted GE/Honeywell merger involved over 500,000 employees worldwide. Add to that the extra complexity of different countries, cultures, time zones and languages, and it becomes easier to see why so many acquisitions fail.

In the acquisition wave of the late 1990s, most successful mega-acquirers used external consultants to assist with implementation, which was considered a unique skill and process. There were additionally at the time few companies with the in-house expertise to undertake large-scale implementation on their own. Moreover, many employers felt they had insufficient manpower. After completing acquisitions it became clear that, even with consultants, the implementation phase required a large staff. One French banking mega-merger had 50 post-acquisition working-groups each averaging ten employees. This equated to 500 executives working on implementation globally – even before external consultants were added in.

Increasingly, acquirers are bringing the implementation process in-house. Why create a significant internal resource for something that happens only occasionally? In the long term, it may cost less than hiring consultants, who can charge up to £15 million a month for mega-acquisitions. It also offers companies greater control over the process. Over time, a company’s internal M&A skills may become so well-honed that it becomes much more likely to make future deals succeed. In some cases, acquisition implementation can become a source of competitive advantage.

Potential acquirers can choose to maintain a separate implementation team, as does GE Capital, though this is relatively rare. The team remains a separate entity and is called upon to integrate several acquisitions as they arise. This is the most expensive option and requires several acquisitions or other projects to take place over a year to justify the cost. But the company can usually ensure acquisitions are integrated quickly and smoothly.

Other acquirers, such as Lafarge, the French cement producer, have a small but separate M&A unit consisting of only a few individuals. It routinely oversees the integration of acquisitions and supplements its ranks with fellow employees or external advisers who work on specific tasks. By rotating employees on and off projects, it spreads acquisition expertise throughout the company, rather than confining it to a few integration experts.

However the team is resourced, there should be enough skilled people on the ground from day one. Do not be tempted to add resources on an ad hoc basis. Once the team is in place, each member should prepare a detailed project plan for their specific area of operation. To do this they must be absolutely clear about what they need to do, and how their roles relate to the overall goals of the acquisition.

A properly structured and resourced induction plan therefore avoids throwing any new team members in at the deep end. They need to understand:

- The acquisition rationale and how it fits the overall company strategy

- The key drivers of success and failure of the acquisition

- Their specific role within the overall team and how this relates to the overall objective

- Who else is in the team and who to turn to for assistance

- Any bonuses available for on-target completion of the tasks.

Prioritise what needs to be done

The integration manager will have the overall responsibility for co-ordinating the development and fine-tuning of the project plan. This will involve:

- Liaising with the negotiation team on the investment requirements to achieve required objectives

- Briefing the due diligence team on the key risk components

- Briefing senior management on task definition and resource requirements

- Delegating individual elements of the project plan to specific integration team members.

Once the plan comes together, the integration manager has to decide what needs to be done in what order. As with most activities, 80 per cent of the wins will be generated by 20 per cent of the activities. Focusing on the projects which yield the highest financial impact in the shortest time has two benefits:

- It helps secure early wins. In contrast to the naive optimism of many top managers, the initial feeling on the part of both workforces is that it will not succeed. The only things that will get buy-in are well-communicated tangible wins to convince employees that there is a brighter future.

- It helps shorten the process by completing the most important projects first.

Traditionally the early effort focuses on reducing costs, but reducing costs often proves more difficult than first thought. What looks like a simple business of eliminating duplication and reducing unnecessary overhead always turns out to be a complex, long-term re-engineering job in which work processes and procedures are fundamentally reorganised, people are redeployed and additional investment in training is needed – oh, and everything has to be achieved with a demotivated workforce.

Depending on the extent of the integration, there is bound to be duplication and everyone internally will be aware of this. The best way forward is to deal with any such redundant effort then get on with capturing the longer-term, growth-orientated benefits. Do not get hung up on cost savings for their own sake: they are a one-off. Once they have been realised there is nothing left. Growth, on the other hand, continues forever.

Get the reporting right

At each stage of the development of the pre- and post-acquisition plan, managers must maintain information systems, including a detailed checklist, and ensure it is completed at each stage. Some managers may choose to use project management software for this purpose. Software can help to integrate cash flow and resource demands and conflicts into a coherent and integrated action plan. Developing a coherent project plan also provides a framework for assessing risk profiles.

Without quality data it is impossible to monitor the integration process. The acquired company quickly needs to start reporting in the standard format.

Overlap with the due diligence team

All the evidence suggests that the most effective integration managers are those that serve on the due diligence team.

It is vital to have a dedicated group focusing purely on integration; it must not be distracted by other operational requirements. This focus will enable the group to:

- Research the market and the company and fully understand the target.

- Ask the right questions of the due diligence providers.

- Consider the operational problems that should be resolved following the deal.

- Plan how to achieve the desired value-add.

By understanding the operational and market dynamics of the acquisition in detail, the team will be able to evaluate and value the target. This quality of understanding and insight also strengthens the hand of the negotiating team.

If the integration team can hit the ground running and win the support of the acquired company, it can then implement change rapidly and avoid the immediate erosion of value.

Remember, though, that the integration and bid teams should be balanced as they perform different roles and the integration manager has different priorities to the negotiating team. His or her role is conciliatory and about building trust and value. It is not adversarial, as that of the negotiating team can be, particularly when there is some tough deal-doing. Figure 5.3 illustrates these roles.

FIGURE 5.3 Roles performed in the bid and integration process

Additional staff from the target company may join the team post acquisition. This will depend on the initial assessment of the acquired company’s management teams and the personnel review, which is part of the week one activities (see later in this chapter). Acquisition planning should always be prepared for the worst case – that none or few of the target’s managers will be suitable for key integration roles in the early post-acquisition stages.

5. Soft issues are paramount

The management of a buying firm should pay at least as much attention to the issues of cultural fit during the pre-merger search process as they do to the issues of strategic fit. Acquirers often find it difficult to see that cultural differences are significant barriers to progress and find it hard to accept that cultural barriers cannot be dismantled quickly or easily.

Get people to work together

The best way to overcome cultural problems is to get people working together to solve problems. Short-term projects that focus on achieving results quickly involving employees from both companies almost always serve to bridge the cultural gap. Employee involvement and participation empowers them and provides them with higher job satisfaction and commitment to the organisation. Employees who are involved in the acquisitions process will demonstrate higher levels of identification when compared with employees only indirectly involved. Get managers to communicate rather than using communications professionals because they will not just say the words but also engage in a dialogue.

The integration plan

In outline, the plan has three phases, as shown in Table 5.5.

TABLE 5.5 Integration phases

| Phase | Activity |

| Day one/week one | Clear communication to employees and other stakeholders Immediate and urgent items required to ensure that key elements of control are transferred smoothly and efficiently |

| The 100-day plan | Introduction of any major changes in operating and personnel practices |

| Year one | Introduction of additional procedures and longer-term staff and business development practices |

Day one

The first day of a new acquisition is crucial. On day one the acquirer should plan to complete a series of essential actions during the day and then review progress at the end of the day. The acquirer’s soft and hard objectives for the day include:

- Gaining control

- Showing that the acquirer means business

- Showing that the acquirer cares about the target

- Winning the hearts and minds of the new employees

- Providing clear guidelines about how the next stages will develop.

Also from day one the acquirer must secure what it has bought. This means ensuring that the new acquisition will start to provide value to the new enlarged organisation. Day one actions affect the development of key tangible and intangible assets, including:

- People

- Products

- IPR

- Plant

- Premises

- Customers

- Suppliers.

Every member of the post-acquisition team will have clear targets to achieve on day one. The acquirer needs to follow the post-acquisition plan closely. There is no time to discuss what needs to be done – this has all been planned, discussed and reviewed prior to the acquisition. The acquirer needs to take action rapidly, calmly and in a systematic manner.

Day-one communication

For the day-one announcement and explanation of the future, personal contact is best; this means individual or group meetings. These should be supported by useful documentation. Ideally this is a tailor-made presentation, which describes the acquirer and explains exactly what this will mean for the acquired company and particularly for its employees. In addition, the acquiring company should have sufficient copies of basic documents such as its:

- Company website address

- Company annual accounts

- Terms and conditions of the company’s pension scheme

- Standard operating procedures where relevant.

Acquired employees are often reassured once they are clear about future strategy, policies and procedures.

Be prepared for the obvious questions

The uncertainty surrounding an acquisition will manifest itself in ‘what about me’ questions such as:

- Will the combined company continue to employ me?

- Will I continue to work in the same place with the same colleagues?

- Is my workload about to increase?

- Will I have a new boss?

- Will I get the same level of current benefits?

- Will my potential future benefits be better or worse?

- Have my longer-term prospects for career development improved or got worse?

- Will my status change?

- Will my lifestyle change?

The questions and the emotions behind these questions will also change as the deal proceeds from its early days to full integration. The common different emotions are shown in Table 5.6.

TABLE 5.6 Good people management during the first days depends on understanding employee emotions

| Event/action | Employee emotion | Disaster avoidance |

| Deal planned | Understand culture, motivations and priorities Avoid rumours | |

| News breaks | ‘Wow! We’re being taken over!…’ | Communicate clearly and effectively to everyone, immediately |

| News sinks in | ‘What does that mean for me?’ | Check the right message actually sank in |

| First Monday | ‘So what happens now then?’ | Clarify initial implications and changes |

| Operational intentions stated | ‘Is that change good for me?’ ‘Will it really happen?’ | Understand perceived implications and any barriers to making things happen |

| First actions | ‘That is/is not what they [officially] said they would do.’ | Build trust through consistency |

| First operational problem | ‘I don’t like that… things used not to be like this.’ | Deal with problems quickly and build confidence that they will not be repeated |

If the acquirer does not act quickly and coherently, employees within both organisations will become increasingly unsettled. They will start to focus on their current situation and spend time doing things which are not much use, such as:

- Spreading rumours and listening to other people’s gossip

- Trying to find out about any changes and the latest news

- Looking for a new job.

Productivity declines and key employees leave. The pharmaceutical mergers of the 1990s saw the mass exodus of senior managers from many of the acquired companies. Remember that the true cost of replacing key employees is a significant proportion of their first year’s salary. This takes into account productivity loss during recruitment, recruitment cost and low productivity of the replacement during induction. Put simply: the acquirer must get to the key employees early, with the right message.

Senior management from the acquirer should be involved because the people in the acquired business need to see and believe that the new parent takes them seriously: ‘Well, the big boss did make the effort to come all the way from London to see us.’ Therefore, senior management within the parent should be part of the communication team, on site, on day one, even for minor acquisitions. Senior managers must be seen to be interested in the future of the new organisation.

As the day-to-day management of the acquisition has been delegated to the acquisition team, senior management can perform a vital role of ‘management by walking about’; meeting employees, customers and suppliers to demonstrate their level of commitment to the smooth development of the new combined organisation.

Financial control

It is essential that financial control passes from the acquired company to the parent at once. This ensures that:

- Potential liabilities are limited to those existing at the time of acquisition

- The company has time to verify financial management procedures in the acquired company and review security procedures

- The ownership of assets is immediately clarified.

Obviously much of the groundwork will have been covered during due diligence. With the right preparation and resources, harmonising financial controls should be relatively straightforward.

At the end of day one, the integration team should review progress against the day one action plan. Any additional actions, which become necessary during the next stages of the integration, can be agreed.

Week one

Creating clear targets for the week one review forces the pace of reform – and ensures that the acquirer has a defined position from which any additional corrective action can be taken to ensure that targets are met. Week one will see the completion of a number of tasks which will shape the structure of the organisation. At the end of week one the acquirer needs to have:

- Completed the initial communication plan to all stakeholders

- Completed the personnel review and confirmed the new company structure

- Started the consultation process on any redundancies

- Gained complete commercial control of the organisation

- If not already done, established clearly what action needs to be taken to further integrate the company’s:

- Management structure

- Financial management

- Personnel management and development

- Legal compliance including health and safety

- Quality control systems

- Information systems

- Marketing and customer interface.

While following its plan and avoiding the temptation to dither, the team must spot and assess unforeseen barriers to integration as early as possible. It will also need to be on the look-out for any adaptations to the plan needed to accommodate what has been found out on the ground.

Month one

The month one review is an important step towards the successful conclusion of integration. At this stage the acquirer needs to review progress and identify bottlenecks.

Typically the month one review will cover the following areas in considerable detail:

- Management quality and stability

- Customer contracts and pricing structures

- Logistics evaluation

- Sales force evaluation and future plan

- Marketing planning

- Integration of customer relationship management (CRM) functions with the parent company

- Stock holding

- Plant analysis and maintenance

- Product analysis; in-house versus subcontracting

- Supplier base

- Asset analysis

- Information and reporting systems

- Contingency plan.

Whilst there will always be the need to focus on the immediate, for example a problem with a key customer, this should not be at the expense of this thorough review. Maintaining a structured methodology with tasks, timelines and milestones will continue to ensure that there is a clear integration roadmap. The target remains to achieve the planned gains. The entire post-acquisition team, plus relevant senior management from the new company, should attend the review. Set aside a full day and meet off-site to avoid distractions.

One hundred days

All major decisions should be completed within 100 days. One hundred days is perhaps an arbitrary time frame but it is put forward by a host of writers and consultants as a turning point in the integration. Private equity investors tend to find that at this stage they can forecast the likely success of their investments. The first one or two board meetings will have taken place and the immediate financial performance of the business will be visible.

By this time, the acquirer should have signed off on:

- Organisational structure, manpower requirements

- Personnel development, compensation structures

- Location decisions

- Asset management, maintenance

- Product range decisions

- Company procedures

- Financial management

- Current supplier agreements and how they are going to be changed

- Customer agreements, channel and pricing policies.

By the end of 100 days the acquirer should be in the position to confirm the potential savings and benefits that will come from the acquisition. Senior management can respond to the implications of this information and, if necessary, instigate new company-wide initiatives.

Continual updating of the project plan reduces the uncertainty surrounding the achievement of the 100-day target. Where tasks are slipping outside their initial planned duration, the team leader can decide to increase resources or deal with areas of conflict within the company.

Each of the divisional leaders within the acquisition team has their own responsibilities laid down in the project plan. These need to be regularly reviewed and then presented at a formal meeting at the end of the 100-day period.

An acquisition is a time of great stress. Having been through the process it is a good idea to codify the lessons learnt so that next time the people involved have the benefit of the company’s acquired experience. For this reason, roughly 12 months after the deal is signed, make time for a post-acquisition review.

Post-acquisition review

The acquisition review allows everyone involved in the acquisition to assess and learn. It is vital for acquirers to learn about what went right or wrong in the acquisition process. Even the most experienced acquirers will make mistakes, but it is foolhardy to repeat those already made elsewhere.

The post-acquisition review will affect the value that an acquirer will put on future acquisitions. It should gain valuable insights into the way in which it:

- Develops an acquisition rationale

- Values a prospective target

- Researches a prospective target

- Negotiates an acquisition

- Plans post-acquisition activities

- Implements its post-acquisition plan.

As it is so valuable, the acquirer should be prepared to put aside sufficient time and resources to ensure that the review is done properly. It will take a lot of time and effort, so it is best organised by the relevant board member. It should include all key players in the acquisition – the acquisition team, negotiators, due diligence providers, board members and so on.

Ideally everyone involved should produce a review document for circulation prior to an open discussion. The group can then:

- Compare the various stages of the project plan to actual events and assess the impact of major variances.

- Capture the lessons learnt in a formal acquisition ‘guidelines’ document.

What the review provides is a mechanism for making better judgements about future acquisitions. From identifying whether initial assumptions were correct, to the actions that the acquirer took to convert the theory into reality, these all help to improve the performance of future acquisitions. Experience shows that the return on investment of this type of review can be very significant.

It is the board’s job to ensure that the lessons of the past acquisition are formally integrated into the standard acquisition document and that the analysis is added to the company literature concerning acquisition.

Acquisition guidelines

A systematic planning process increases the odds of a successful acquisition. People planning the deal need accurate and consistent information about integration. They should not be ‘reinventing the wheel’ when time is short. Bespoke guidelines can also help when selecting and managing consultants, helping to ensure they operate within the company’s parameters without duplicating work.

Guidelines must be flexible enough to cover various types of acquisitions and different degrees of integration. For instance, a foreign subsidiary acquisition operating in a stand-alone capacity may require more input from the finance and IT departments. Conversely, a full merger of two operations may need more attention from HR over employment legislation and communication and cultural matters.

Acquisition guidelines should be revisited after each acquisition and the necessary changes made to the structure of the plan, its reporting and evaluation methodology. The acquirer should use the post-acquisition review to learn the key successes and failures. These must be incorporated into the acquisition guidelines. This ‘library’ will be a growing resource which will give those individuals new to acquisition and acquisition planning a vital resource to improve their understanding of what needs to be planned and implemented and how to overcome problems.

As the integration manager has now inevitably moved on to other responsibilities, it is important that the responsibility for the review and upgrading of the standard operating procedures towards post-acquisition integration should be maintained at the highest level within the organisation.

Conclusion

Start thinking about integration right at the beginning of the process. We argue above that it is impossible to value a business without a pretty good idea of where the synergies will come from and how they will be captured, so it would be highly unprofessional not to have thought about integration right at the outset. As important is the body of evidence which tells us that the major cause of acquisition failure is poor integration. Doing the deal may be sexier, but integration is where the real money is made or lost. For goodness sake, make sure due diligence is structured to help with integration and not solely slanted towards completing the deal. Integration requires a completely different approach to transacting, thus it needs a separate team with its own leader who is responsible for progress. But that team must work closely with the deal team. Indeed it is highly likely that some individuals will be involved in both the transaction and the resulting integration.

Integration needs to be quick, but, apart from putting together a detailed plan of action, the main concern of the integration team should be to identify and deal with the soft issues which may act as a drag on quick and successful integration. Finally, once the dust has settled, learn from the experience. Carrying out a post-acquisition review introduces a typical planning loop into acquisitions, namely: do something, learn about it and incorporate the results.