Chapter 17

Planning, control and performance: Budgeting

Slogan at Japanese Company, Topcom (Economist, 13 January 1996)

Source: The Wiley Book of Business Quotations (1998), p. 90.

Learning Outcomes

After completing this chapter you should be able to:

- Explain the nature and importance of budgeting.

- Outline the most important budgets.

- Prepare the major budgets and a master budget.

- Discuss the behavioural implications of budgets.

Go online to discover the extra features for this chapter at www.wiley.com/college/jones

Go online to discover the extra features for this chapter at www.wiley.com/college/jones

Chapter Summary

- The two major branches of cost accounting are costing, and planning, control and performance.

- Budgeting is a key element of planning, control and performance.

- Budgets are ways of turning a firm's strategic objectives into practical reality.

- Most businesses prepare, at the minimum, a cash budget.

- Large businesses may also prepare a revenue, a trade receivables and a trade payables budget.

- Manufacturing businesses may prepare a raw materials, a production cost and a finished goods budget.

- Individual budgets fit into a budgeted income statement and a budgeted statement of financial position.

- Budgeting has behavioural implications for the motivation of employees.

- Some behavioural aspects of budgets are spending to budget, padding the budget and creative budgeting.

- Responsibility accounting may involve budget centres and performance measurement.

Introduction

Cost accounting can be divided into costing, and planning, control and performance. Budgeting and standard costing are the major parts of planning, control and performance. Budgeting, or budgetary control, is a key part of businesses' planning for the future. A budget is essentially a plan for the future. Budgets are thus set in advance as a way to quantify a firm's objectives. Actual performance is then monitored against budgeted performance. For small businesses, the cash budget is often the only budget. Larger businesses, by contrast, are likely to have a complex set of interrelating budgets. These build up into a budgeted income statement and budgeted statement of financial position. Although usually set for a year, budgets are also linked to the longer-term strategic objectives of an organisation.

Management Accounting Control Systems

A business needs systems to control its activities. Budgeting and standard costing are two essential management control systems that enable a business to run effectively. They represent an assemblage of management accounting techniques which enable a business to plan, monitor and control ongoing financial activities. A particular aspect of a management accounting control system is that it is often set up to facilitate performance evaluation. Performance evaluation involves evaluating the performance of either individuals or departments. A key facet of performance evaluation is whether it is possible to allocate responsibility and whether the costs are controllable or uncontrollable.

Nature of Budgeting

In many ways, it would be surprising if businesses did not budget. For budgeting is part of our normal everyday lives. Whether it is a shopping trip, a university term or a night out on the town, we all generally have an informal budget of the amount we wish to spend. Businesses merely have a more formal version of this ‘informal’ personal budget.

Personal Budgets

You are planning to jet off for an Easter break in the Mediterranean sun. What sort of items would you include in your holiday budget?

There would be a range of items, for example,

- transport costs to and from the airport

- cost of flight to Mediterranean

- cost of hotel

- cost of meals

- spending money

- entertainment money

- money for gifts

All these together would contribute to your holiday budget.

Budgeting

‘While most managers dislike having to deal with them, budgets are nevertheless essential to the management and control of an organization. Indeed, budgets are one of the most important tools management has for leading an organization toward its goals.’

Source: Christopher Bart (1988), Budgeting Gamesmanship, Accounting of Management Executive, p. 285. Reprinted in S.M. Young, Readings in Management Accounting, Third Edition, 2001.

Planning, control and performance is one of the two major branches of cost accounting. This is shown in Figure 17.1.

Standard costing is, in reality, a more tightly controlled and specialised type of budget. Although often associated with manufacturing industry, standard costs can, in fact, be used in a wide range of businesses.

Budgeting can be viewed as a way of turning a firm's long-term strategic objectives into reality. As Figure 17.2 shows, a business's objectives are turned into forecasts and plans. These plans are then compared with the actual results and performance is evaluated.

In small businesses, this process may be relatively informal. However, for large businesses there will be a complex budgeting process. The period of a budget varies. Often there is an annual budget broken down into smaller periods such as months or even weeks.

As Definition 17.1 shows, a budget is a quantitative financial plan, which sets out a business's targets.

Working definition

A future plan which sets out a business's financial targets.

Formal definition

‘Quantitative expression of a plan for a defined period of time. It may include planned sales volumes and revenues, resource quantities, costs and expenses, assets, liabilities and cash flows.’

Source: Chartered Institute of Management Accountants (2005), Official Terminology. Reproduced by Permission of Elsevier.

Four major aspects of budgets are planning, coordinating, motivation and control. Budgets, therefore, combine both technical and behavioural features. Budgets can be used for performance evaluation. These behavioural aspects and performance evaluation are discussed more fully later in the chapter.

(i) Planning

This involves setting out a comprehensive plan appropriate to the business. For small businesses, this may mean a cash budget. For larger businesses, there will probably be a formalised and sophisticated budgeting system. Planning enables businesses to balance their short-term operations with their future intended activities.

(ii) Coordinating

A key aspect of the budgetary process is that it relates the various activities of a company to each other. Therefore, revenue is related to purchases, and purchases to production. This needs to be done so that, for example, the correct amount of inventory is held. The business can be viewed as an interlocking whole.

(iii) Motivation

By setting targets the budget has important motivational aspects. If the targets are too hard, they can be demotivating. If too easy, they will not provide any motivation at all. The motivational aspects of budget setting can be very helpful to businesses, but, as we will see later, they can also lead to behavioural responses from employers such as padding the budget.

(iv) Control

This is achieved through a system of making individual managers responsible for individual budgets. When actual results are compared against target results, individual managers will be asked to explain any differences (or variances). The manager's performance is then evaluated. Budgets, as Real-World View 17.1 shows, are an indispensable form of administrative control and accountability. Formal performance evaluation mechanisms such as responsibility accounting are often introduced.

Budgetary Control and Responsibility

Budgetary control and responsibility accounting have been the foundation of management control systems design and use in most business (and other) organizations for many years. But whereas in the 1960s and 1970s such systems were almost exclusively based on management accounting information, more recently we have seen a recognition that a wider set of tools are required involving both the use of a range of non-financial performance measures and alternative concepts of accountability such as value chain management. Nevertheless, the focus remains on accountability arrangements within and outside organisations, and on taking a broad, holistic approach to the management of organizational performance.

Source: D. Otley (2006), Trends in budgeting control and responsibility accounting, in A. Bhimani, Contemporary Issues in Management Accounting, Oxford University Press, p. 291.

In large businesses, budgets are generally set by a budgetary committee. This will normally involve managers from many different departments. The sales manager, for example, may provide information on likely future revenue, which will form the basis of the revenue budget. However, it is important that individual budgets are meshed together to provide a coordinated and coherent plan. As Soundbite 17.2 shows, the starting point for this year's budget is usually last year's budget. A form of budgeting called zero based budgeting assumes the activities are being incurred for the first time. This approach forces businesses to look at all activities from scratch and see if they are necessary. It is very time-consuming, but can be particularly useful as a one-off exercise which necessitates managers reviewing all activities of the business as if for the first time. The budgetary process is normally ongoing, however, with meetings during the year to review progress against the current budget and to set future budgets.

Last Year's Budget

‘The largest determining factor of the size and content of this year's budget is last year's budget.’

Aaron Wildavsky, The Politics of the Budgetary Process, 1964

Source: The Executive's Book of Quotations (1994), p. 39. Oxford University Press.

Although budgets are set within the business, external factors will often constrain them. A key external constraint is demand. It is futile for a company to plan to make ten million motorised skateboards if there is demand for only five million. Indeed, potential revenue is the principal factor that limits the expansion of many businesses. Usually, the revenue budget is determined first. Some businesses employ a materials requirement planning (MRP) system. Based on revenue demand, MRP coordinates production and purchasing to ensure the optimal flow of raw materials and optimal level of raw material inventory. Another important budgetary constraint in manufacturing industry is production capacity. It is useless planning to sell ten million motorised skateboards if the production capacity is only five million. A key element of the budgetary process is thus harmonising demand and supply.

Nowadays, it is rare for businesses not to have budgets. As Figure 17.3 shows, budgets have many advantages. The chief disadvantages are that budgets can be inflexible and create behavioural problems. Budgets can be inflexible if set for a year. It is common to revise budgets regularly to take account of new circumstances. This is easier when they are prepared using spreadsheets. The behavioural problems may be created, for example, when individuals attempt to manipulate the budgeting process in their own interest. This is discussed later.

Budgets

Budgets are often said to create inflexibility as they are typically set for a year in advance. Can you think of any ways to overcome this inflexibility?

This inflexibility can be dealt with in two ways: rolling budgets and flexible budgets. With rolling budgets the budget is updated every month. There is then a new twelve-month budget. The problem with rolling budgets is that it takes a lot of time and effort to update budgets regularly. Flexible budgets attempt to deal with inflexibility by setting a range of budgets with different activity levels. So a company might budget for servicing 100,000, 150,000 or 200,000 customers. In this case, there would, in effect, be three budgets for three different levels of business activity.

Cash Budget

The cash budget is probably the most important of all budgets. Almost all companies prepare one. Indeed, banks will often insist on a cash budget before they lend money to small businesses. For a sole trader, the cash budget is often as important as the income statement and statement of financial position. It reflects the need to balance profitability and liquidity. There are similarities, but also differences, between the cash budget and the statement of cash flows that we saw in Chapter 8. They are similar in that both the cash budget and statement of cash flows chart the flows of cash within a business. The differences arise in that the statement of cash flows is normally prepared in a standardised format in accordance with accounting regulations and looks backwards in time. By contrast, the cash budget is not in a standardised format and unlike the statement of cash flows looks forward in time.

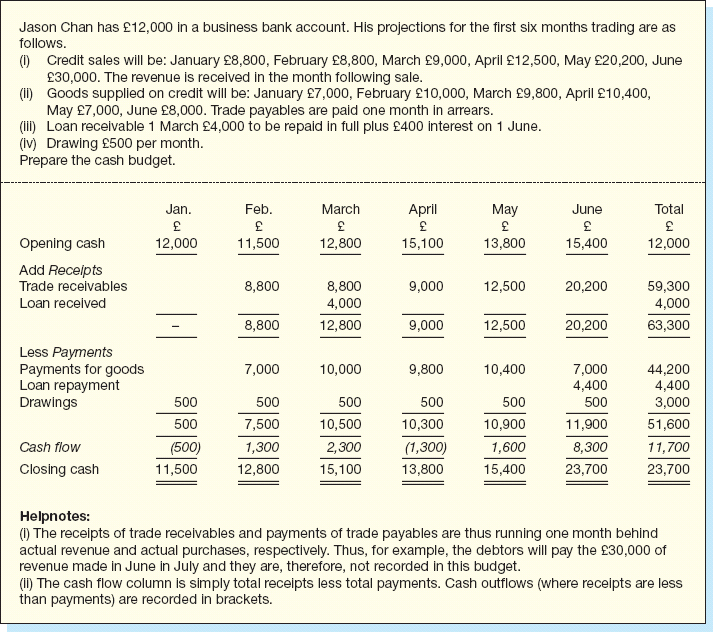

Essentially, the cash budget looks into the future. Figure 17.4 gives the format of the cash budget. We start with the opening cash balance. Receipts are then recorded, for example, cash received from cash sales, from trade receivables or from the sale of property, plant and equipment. Cash payments are then listed, for example, cash purchases of goods, payments to trade payables or expenses paid. Receipts less payments provide the monthly cash flow. Opening cash and cash flow determine the closing cash balance.

In Figure 17.5 on the next page, we show an actual example of how in practice a cash budget is constructed.

Other Budgets

A business may have numerous other budgets. Indeed, each department of a large business is likely to have a budget. In this section, we will look at three key budgets common to many businesses: revenue budget, trade receivables budget and trade payables budget. In the next section, we will look at three additional budgets that are commonly found in manufacturing businesses: raw materials budget, finished goods budget and production cost budget. Finally, we will bring the budgets together in a comprehensive example.

(i) Revenue Budget

The revenue budget is determined by examining how much the business is likely to sell during the forthcoming period. Figure 17.6 provides an example. Revenue budgets like many other budgets can be initially expressed in units before being converted to £s. In many businesses, the revenue budget is the key budget as it determines the other budgets. The revenue budget is, therefore, often set first.

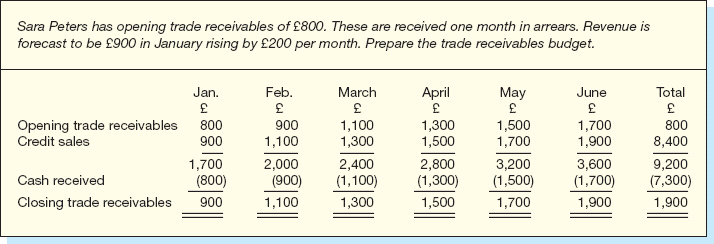

(ii) Trade Receivables Budget

The trade receivables budget begins with opening trade receivables (often taken from the opening statement of financial position) to which are added credit sales (often taken from the revenue budget). Cash receipts are then deducted, leaving closing trade receivables. An example of the format for a trade receivables budget is provided in Figures 17.7 and 17.8.

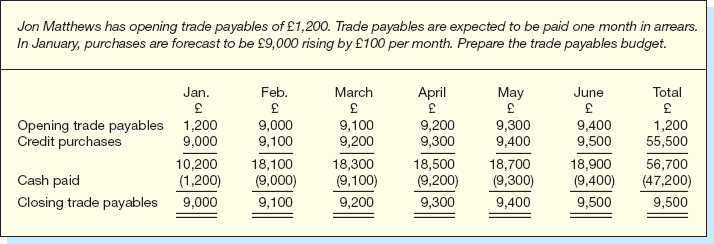

(iii) Trade Payables Budget

In many ways, the trade payables budget is the mirror image of the trade receivables budget. It starts with opening trade payables (often taken from the opening statement of financial position), adds credit purchases and then deducts cash paid. The result is closing trade payables. The format for the trade payables budget is given in Figure 17.9, while Figure 17.10 provides an illustrative example.

Manufacturing Budgets

Manufacturing companies normally hold more inventory than other businesses. It is, therefore, common to find three additional budgets: a production cost budget, a raw materials budget and a finished goods budget. Often these budgets are expressed in units, which are then converted into £s. For ease of understanding, we express them here only in financial terms.

(i) Production Cost Budget

The production cost budget, as its name suggests, estimates the cost of production. This involves direct labour, direct materials and production overheads. There may often be sub-budgets for each of these items. The production cost format is shown in Figure 17.11, while Figure 17.12 shows an example. Once the production cost is determined, the finished goods budget can be prepared. It is important to realise that the budgeted production levels are generally determined by the amount the business can sell.

(ii) Raw Materials Budget

The raw materials budget is particularly useful as it provides a forecast of how much raw material the company needs to buy. This can supply the purchases figure for the trade payables budget. The raw materials budget format is shown in Figure 17.13. It starts with opening inventory of raw materials (often taken from the opening statement of financial position); purchases are then added. The amount used in production is then subtracted, arriving at closing inventory. An example is shown in Figure 17.14.

(iii) Finished Goods Budget

The finished goods budget is similar to the raw materials budget except it deals with finished goods. As Figure 17.15 shows, it starts with the opening inventory of finished goods (often taken from the statement of financial position), the amount produced is then added (from the production cost budget). The cost of sales (i.e., cost of the goods sold) is then deducted. Finally, it finishes with the closing inventory of finished goods. The finished goods budget is useful for keeping a check on whether the business is producing sufficient goods to meet demand. Figure 17.16 gives an example of a finished goods budget.

Comprehensive Budgeting Example

Once all the budget have been prepared, it is important to gain an overview of how the business is expected to perform. Normally, a budgeted income statement and budgeted statement of financial position are drawn up. This is often called a master budget. The full process is now illustrated using the example of Jacobs Engineering (see Figure 17.17), a manufacturing company. A manufacturing company is used so as to illustrate the full range of budgets discussed in this chapter. From Figure 17.17, the interlocking nature of the budgetary process can be seen. To take one example, for the trade receivables budget: the totals from the revenue budget are fed into the trade receivables budget as credit sales, while the cash received from trade receivables in the cash budget also appears in the trade receivables budget.

An overview of the whole process is presented in Figure 17.18. This shows how the various budgets interlock. It must be appreciated that Figure 17.18 does not include all possible budgets (for example, many businesses have labour, selling and administration budgets). However, Figure 17.18 does give a good appreciation of the basic budgetary flows.

After the budgetary period, the actual results are compared against the budgeted results. Any differences between the two sets of results will be investigated and action taken, if appropriate. This basic principle of investigating why any variances have occurred is common in both budgeting and standard costing.

Behavioural Aspects of Budgeting

It is important to realise that there are several, sometimes competing, functions of budgets, for example, planning, coordinating, motivation and control. Budgeting is thus a mixture of technical (planning and coordinating) and behavioural (motivation and control) aspects. In short, budgets affect the behaviour of individuals within firms.

Importance of budgets

‘While most managers dislike having to deal with them, budgets are nevertheless essential to the management and control of an organisation. Indeed, budgets are one of the most important tools management has for leading an organisation toward its goals.’

Source: C.K. Bart (1988), Budgeting Gamesmanship in S.M. Young (2001), Readings in Management Accounting, p. 217.

The budgetary process is all about setting targets and individuals meeting those targets. As Real-World View 17.2 shows, a senior supply chain manager demonstrates that managers strive, using all possible means, to meet their targets.

Meeting Targets

I try to make sure I hit the target so if we had to spend more on air freight we find it somewhere else … if there is a variance you are expected to offset it with something else. For instance, next year I fully expect currency to go adverse. Does that mean to say that we will get lower targets? No … if I was to sit back here and say: ‘Well, currency has hit me, I can't do anything’, I wouldn't be in the job for very long. The thing is not to sit there and say: ‘All the world is against me’ … Find another way.

Source: Reprinted from Accounting, Organizations and Society, Vol. 35, by authors: N. Frow, D. Marginson and S. Ogden, ‘Continuous’ Budgeting: Reconciling Budget Flexibility With Budgeting Control. page 454, Copyright 2010, with permission from Elsevier.

The problem is that an optimal target for the business is not necessarily optimal for the individual employee. Conflicts of interest, therefore, arise between the individual and the company. It may, for example, be in a company's interests to set a very demanding budget. However, it is not necessarily in the employee's interests. Budgets can, therefore, have powerful motivational or demotivational effects. For employees, in particular, budgets are often treated with great suspicion. Top managers often use budgets deliberately as a motivational tool. Managers lower down in the organisation often develop strategies to cope with imposed budgets (see Real-World View 17.3).

The Games that Product Managers Play

Although they never referred to them as ‘games’ per se, the product managers interviewed were not wanting for a rather extensive lexicon to describe their budgeting manipulations. ‘Cushion,’ ‘slush fund,’ ‘hedge,’ ‘flexibility,’ ‘cookie jar,’ ‘hip/back pocket,’ ‘pad,’ ‘kitty,’ ‘secret reserve,’ ‘war chest,’ and ‘contingency’ were just some of the colourful terms used to label the games that managers played with their financial forecasts and budgets. For the most part, however, all of these terms could be used interchangeably.

Source: C.K. Bart (1988), Budgeting Gamesmanship, in S.M. Young (2001), Readings in Management Accounting, p. 218.

Balancing Budgetary Needs

‘Attempting to use a budget system to give effective short-term control whilst encouraging managers to make accurate estimates of future outcomes has long been recognised as a knife-edge that managers need to walk’.

Source: D. Otley (2006) Trends in Budgetary control and responsibility accounting, in A. Bhimani, Contemporary Issues in Management Accounting, Oxford University Press, p. 292.

To demonstrate the behavioural impact of budgeting, we look below at three behavioural practices associated with budgeting: spending to budget, padding the budget and creative budgeting.

(i) Spending to Budget

Many companies allocate their expense budget for the year. If the budget is not spent, then the department loses the money. This is a double whammy as often next year's budget is based on this year's. So an underspend this year will also result in less to spend next year. It is in managers' individual interests (but not necessarily in the firm's interests) to avoid this. Managers, therefore, will spend money at the last minute on items such as recarpeting of offices. This is the idea behind the cartoon at the start of this chapter!

Jane Morris has a department and was allocated £120,000 to spend for year ended 31 December 2012. In 2013, the budget is based on the 2012 budget plus 10% inflation. She spends prudently so that by 1 December 2012 she has spent £90,000. Normal expenditure would be a further £10,000. Thus, she would have spent £100,000 in total. What might she do?

Well, it is possible she might give the £20,000 (£120,000–£100,000) unspent back to head office. However, this will result in only £110,000 (£100,000 + 10%) next year. More likely she will try to spend the surplus. For example, buy

- a new computer

- new office furniture

- new carpets

(ii) Padding the Budget

Budgets are set by people. Therefore, there is a great temptation for individuals to try to create slack in the system to give themselves some leeway. For example, you might think that your department's revenue next year will be £120,000 and the expenses will be £90,000. Therefore, you think you will make £30,000 profit. However, at the budgetary committee you might argue that your revenue will be only £110,000 and your expenses will be £100,000. You are, therefore, attempting to set the budget so that your profit is £10,000 (i.e., £110,000 – £100,000). You have, therefore, built in £20,000 budgetary slack (£30,000 profit [true estimated position] less £10,000 profit [argued position]). Real-World View 17.4 demonstrates the behavioural aspects involved in padding the budget.

Padding the Budget

Another condition identified as facilitating budgeting games was the time constraints imposed on senior management during the product plan review period. As one manager put it:

‘Senior management just doesn't have the time

for checking every number you put into your

plans .… So one strategy is to “pad” everything.

if you're lucky, you'll still have 50% of your

cushions after the plan reviews.’

Source: C.K. Bart (1988), Budgetary Gamesmanship, in S.M. Young (2001), Readings in Management Accounting, p. 219.

(iii) Creative Budgeting

If departmental managers are rewarded on the basis of the profit their department makes, then they may indulge in creative budgeting. Creative budgeting may, for example, involve deferring expenditure planned for this year until next year (see, for example, Figure 17.19).

Responsibility Accounting

The behavioural aspects of budgeting can be utilised when designing responsibility accounting systems. In such systems, organisations are divided into budgetary areas, known as responsibility centres. Managers are held accountable for the activities within these centres. As Figure 17.20 shows there are different sorts of responsibility centre.

A revenue centre is totally focused on revenue and exists, for example, in situations where sales managers may be responsible for revenue in their own regions. Cost centres, by contrast, are where the manager just deals with costs, for example, a purchases manager. In profit centres and investment centres, the managers have more responsibility. In investment centres, in particular, managers will have particular autonomy and these centres are usually at subsidiary or group rather than departmental level.

Managers of investment centres thus have more responsibility than those of profit centres who in turn have more responsibility than managers of cost or revenue centres. A key aspect of responsibility accounting is that the manager is responsible for controllable costs, but not uncontrollable costs. Controllable costs are simply those costs that a manager can be expected to influence. An uncontrollable cost is one over which the manager has no control, for example, price rises of purchases caused by suppliers increasing their product prices or adverse movements in exchange rates making the costs of importing goods more expensive.

Responsibility accounting is a way of monitoring the activities of managers and judging their performance. The budgeted costs, revenues and profits are compared with the actual results. Managers can be rewarded or penalised accordingly often by the payment or nonpayment of bonuses.

Investment centres are often evaluated using specific performance measures. Three of the most common are Return on Investment (ROI), Residual Income (RI) and Return on Sales (ROS). These three ratios are outlined in Figure 17.21.

These three ratios all have strengths and weaknesses. Return on Sales is quite simple. However, it does not take into account the investment a company has made in its operations and, therefore, is quite limited in practice. An alternative term for Return on Sales is Return on Revenue. However, Return on Sales (ROS) is used in this book as this is still the most widely used term. Return on Investment is more sophisticated and provides a useful indicator of the firm's profitability. However, it does not take into account a company's desired return on capital. Residual Income, by contrast, does and indicates the profits a company makes over its minimum return.

Below, in Figure 17.22, is an example of how these particular measures may be used in practice. The example of three divisions of an international car hire firm is used, HireCarCo. These are based in London, Paris and Berlin.

Conclusion

Budgeting is planning for the future. This is important as a business needs to compare its actual performance against its targets. Most businesses prepare a cash budget and large businesses often prepare a complex set of interlocking budgets which culminate in a budgeted income statement and a budgeted statement of financial position. Budgets have a human as well as a technical side. As well as being useful for planning and coordination, budgets are used to motivate and monitor individuals. Budgets are often used as the basis for performance evaluation. Sometimes, therefore, the interests of individuals and businesses may conflict.

Discussion Questions

Discussion Questions

Questions with numbers in blue have answers at the back of the book.

| Q1 | What are the advantages and disadvantages of budgeting? |

| Q2 | Why do some people think that the cash budget is the most important budget? Do you agree? |

| Q3 | The behavioural aspects of budgeting are often overlooked, but are extremely important. Do you agree? |

| Q4 | State whether the following statements are true or false? If false, explain why.

(a) The four main aspects of budgets are planning, coordinating, control and motivation. (b) The commonest limiting factor in the budgeting process is production. (c) A master budget is formed by feeding in the results from all the other budgets. (d) Depreciation is commonly found in a cash budget. (e) Spending to budget, padding the budget and creative budgeting are all common behavioural responses to budgeting. |

Numerical Questions

Numerical Questions

Questions with numbers in blue have answers at the back of the book.

Go online to discover the extra features for this chapter at www.wiley.com/college/jones

Go online to discover the extra features for this chapter at www.wiley.com/college/jones

PAUSE FOR THOUGHT 17.1

PAUSE FOR THOUGHT 17.1 SOUNDBITE 17.1

SOUNDBITE 17.1

DEFINITION 17.1

DEFINITION 17.1 REAL-WORLD VIEW 17.1

REAL-WORLD VIEW 17.1