According to the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, the UK’s technology industry is booming and worth £400 million a day, accounting for 7.7% of the whole UK economy (Warman, 2020). The industry is growing year on year, yet BCS’s 2020 annual diversity report shows that women continue to make up just 17% of the digital workforce (BCS, 2020). Despite numerous initiatives, the number of women employed in tech has not moved significantly over the past decade. The industry needs diversity, and a report from the World Economic Forum (2020) indicates that it will take around 257 years for the world to reach gender parity if we continue at the current rate of change. So, where are the women? This chapter looks at some of the challenges organisations face trying to attract women and diverse talent, and addresses how you can improve your chances of attracting women into your organisations.

THE WHAT: THE CHALLENGE AND THE BARRIERS

The challenge is that there is a digital skills gap that is widening and there are not enough people who are adequately skilled to meet the demand of the data-driven future. This is compounded by the lack of diversity and women to fill the deficit. Accenture (2018) has estimated that if the skills gap is not filled by 2028, the UK will forego £141.5 billion of GDP growth (see also Consultancy UK, 2018). The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated organisations’ need to embrace technology and highlighted that there are skills shortages. Digital transformation is impacting every industry, most of which now have growing needs for IT and tech skills in their workforce. This is Industrial Revolution 4.0, and technology advancements includes the Internet of Things, the Industrial Internet of Things, blockchain, quantum computing, machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI). There will be more disruptions as new digital solutions and technologies evolve and emerge. A diverse workforce is needed to fill the skills gap but will moreover be imperative to ensure that the needs of people across society are recognised and prioritised, and that IT is designed to be for the good of everyone.

A 2019 article for the World Economic Forum stated that ‘the European Commission believes there could be as many as 756,000 unfilled jobs in the European ICT sector by 2020’ and this is growing, causing the skills gap to become more acute (Milano, 2019). In 2020, the World Economic Forum reiterated that the biggest challenge organisations face is the skills gap (Parekh, 2020), and an article by Gartner agrees that despite the increase in global unemployment and underemployment rates as a result of COVID-19, there are insufficient resources available to fulfil the roles that organisations require (Panetta, 2020).

To address this deficit and increase their competitive advantage, companies need to look at how they can attract candidates: by increasing diversity within their teams and upskilling people with tools and capabilities they may not have considered or thought they possessed. Attracting women could be the answer. It would certainly help to address three of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals: Quality Education (Goal 4), Gender Equality (Goal 5) and Reduced Inequalities (Goal 10) (United Nations, n.d.). Gender equality is not only a fundamental human right but also a necessary foundation for a peaceful, prosperous and sustainable world as it ensures women are involved in the enhancement of enabling technologies and encourages effective participation at all levels of development and decision-making. Quality education helps to reduce inequalities and ensure gender equality. By offering and promoting learning opportunities, organisations could access and attract a new talent pool (for further information, see Chapter 2).

In 2020, BCS’s diversity report showed that ‘women accounted for 50% of the working age population (those aged 16–64), 48% of those in work and 45% of the unemployed’ (p. 7). However, ‘there were 249,000 female IT specialists in the UK workforce during 2019, or 17% of the total during this period. By comparison, 48% of the wider workforce were women and as such, if parity of representation could be achieved for IT this would equate to an additional 451,000 IT specialists working in the economy’ (p. 9). Despite numerous initiatives to raise the level of female representation in IT, it has remained virtually unchanged for a generation. While the numbers varied between the home nations, the highest, in Wales, only accounted for 21% of IT specialists.

There is a global talent shortage, and according to research from ManpowerGroup this has nearly doubled in the past decade (Bolden-Barrett, 2020). This has been exacerbated by the pandemic, putting increased pressure on organisations to deliver large-scale transformations, and it has shifted the tech skills gap from shortage to drought. An article on Totaljobs states that, in the UK, ‘71% of technology employers expect to face at least a moderate skills shortage in the coming year… and 20% of technology employers agree they need to encourage more females into the sector’ (Green, 2020). So how can companies address this? The answer is by looking for diverse talent in different pools and thinking about how they can attract more varied candidates by signposting career paths and learning journeys.

Good talent is scarce and valuable, so it needs to be fostered. The scarcity and high value of people mean that talent matters, so attracting the right talent is important as it creates a huge opportunity for companies when they get it right. Attracting diverse talent is becoming essential for companies as they accept that diverse teams bring high value to organisations.

Research shows that a company with a good gender balance has more innovative thinking and signals to investors that it is run competently (Hewlett et al., 2013) and more productively (Turban et al., 2019). Other research supports these findings on competency and concludes that gender diversity promotes scientific creativity and innovation (Nielson et al., 2017). A diverse workforce is a reflection of a changing world and marketplace. Candidates are attracted to companies that are outspoken about diversity as they believe this indicates the company is serious about diversity and inclusion rather than just part of the corporate branding. See Chapter 1 for further discussion of the business case for diversity and how diverse groups benefit innovation and innovative thinking.

An article in Catalyst suggests there are three barriers to women in tech-intensive industries (Beninger, 2014):

- Role models: women need to be attracted at all levels because if they can’t see people like themselves throughout an organisation, they will not believe it is possible for them to succeed in that company.

- Feeling like an outsider: companies need to be more inclusive and build psychological safety so teams and individuals can thrive.

- Unclear evaluation criteria: all parties need to agree how they will be assessed and rewarded; without this, you do not have employee engagement. A study found that women who had uncertainty about belonging underperformed in male-dominated science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) fields (Smith et al., 2012).

The low rates of women in tech lessen the chance of girls and young women seeing people like themselves in role models, which in turn perpetuates the lack of women in the pipeline.

THE WHY: THE REASONS FOR GENDER INEQUALITY

Prior to the COVID-19 crisis, the World Economic Forum (2020) predicted that at current rates of progress it will take 257 years to close the economic gender gap and that socioeconomic factors are impacting women disproportionally. As the impact of the pandemic continued to be felt, the World Economic Forum (2021) indicated that the time needed to close the gap has expanded further. Therefore, it is important to take collaborative action now to see how this can be expedited during recovery from the global pandemic to advance economic gender parity.

Human Rights Careers (2021) lists 10 key factors that impact gender inequality, the most relevant of which are:

- lack of employment equality;

- gender bias;

- societal mindsets.

Creating an even playing field for employment will have a knock-on effect of improving other areas of inequality. Society’s views and beliefs have generated entrenched gender biases and stereotypes about who should do what type of role, and it will take positive action to create a significant change.

Sense of purpose and philosophical argument

How do women choose the places they want to work? Many women want a role that gives them an opportunity to make a difference. When a company’s values, purpose and work–life balance are aligned with a woman’s own, they are more likely to consider working for that organisation. Demonstrating how your employees find meaning, fun and flexibility in the way they work will go a long way to attracting women to your roles.

Men and women need to feel they have a purpose; especially after the numerous COVID-19 lockdowns, going to work just to earn money might not be enough going forward. PwC (2021) states that people have a sense of purpose at work when there is meaning to what they do; however, there is a disconnection between this and what leaders want, as they prioritise commercial value. Having a strong sense of purpose in the workplace can improve performance, innovation and commitment; however, employees also want to feel they are making a positive difference to their community, society or the environment. Women’s values and purpose are often aligned with communal goals and STEM roles stereotypically do not address this (Fuesting and Diekman, 2017) and, consequently, women tend to opt for non-STEM careers. Gender socialisation and cultural norms influence values, interest and beliefs about STEM careers (Chapter 4, on unconscious bias, covers socialisation in more depth). A study found that providing more opportunities for leadership and advancement, and giving flexibility around childbearing years, removed societal and biological barriers, which in turn encouraged and motivated women to reconsider STEM careers (Wang and Degol, 2013). Having role models who can demonstrate how they make a difference and add value will attract women.

People need to feel they belong. Through organisations building relationships with potential candidates, they can help to create connections even before the candidates start the application process, which can help people feel supported in the place they would like to work. If they cannot see how they would fit into the team or company, they are not going to be attracted by that team or company, especially if they believe they would need to conform or adopt some of the behaviours and attitudes of the members of the group in order to gain acceptance.

Women generally do not like to blow their own trumpets; instead they prefer or hope to be recognised for what they deliver or produce, believing that this should speak for itself (Stewart, 2015). It is pertinent to recognise that this can affect how women portray themselves both in their CVs and during the interview process. The reason women often understate their achievements is partially due to the way girls are brought up, probably being told not to boast or draw attention to themselves. Although society is changing and people are encouraged to self-promote, many women still think this is self-centred and egotistical whereas women who are confident, capable and ambitious are often considered braggers and unlikeable, and can be socially penalised. However, these same traits are seen as leadership and admirable in men. This gender stereotype conditioning starts in childhood, where parents praise and reward boys for their efforts whereas girls are not praised and rewarded in the same way. A literary review conducted by the Fawcett Society showed that parents inadvertently reinforce gender stereotypes by creating a ‘gendered world’ through toys, play, language and environment; as early as six years old, children associate intelligence with being male and ‘niceness’ with being female (Culhane and Bazeley, 2019). Equally, gender stereotypes can influence the subjects students elect to study at school and university (see Chapters 2 and 3).

THE HOW: OVERVIEW OF HOW TO ATTRACT FEMALE TALENT

How and where do you start to find more women for your organisation? The remainder of this chapter lays out the areas you may want to tackle to ensure that your policies and practices maximise the attraction of technical women to your team. They cover:

- debunking myths;

- advertising and job descriptions;

- the legal mechanisms that can be used to support your work;

- the marketing and branding work that will encourage women to see your organisation as one they would like to work for;

- where and how to find diverse candidates;

- your organisation’s offer to diverse candidates;

- creating an inclusive interview process.

DEBUNKING MYTHS

Before you start looking to attract female talent, we need to debunk a few myths about why women are not attracted to working in tech. It is important for your organisation to talk about the facts; otherwise, they may become embedded biases or assumptions. Research by KPMG, YSC and the 30% Club (2015) helps to debunk the myths. By understanding the reality, you can start to see how you might attract women into your organisation.

This report listed several key findings, two of which are especially important. Firstly, ‘women become more ambitious about senior leadership as their career progresses’. The report suggested this means that organisations should ‘not write women off too early [as] their ambition grows with their experience’. Secondly, ‘childrearing slows women’s careers down only marginally [as] more significant promotion gaps emerge earlier on’. The report suggested that ‘providing career navigation tools to men and women in the early stages of their careers enables them to monitor their individual career progression effectively’ (p. 2).

These myths can also be reflected to girls. Therefore, if we want to build a pipeline of talent, we need to dispel the myths so that they believe they can have a career in tech. If we ignore the myths, they will become self-fulling prophecies.

Welson-Rossman (2018) found that her experiences of founding and running TechGirlz, which has taught over 30,000 girls to code, contributed to her findings about the top 10 myths about girls and tech. These myths are:

- ‘You have to code to be in technology’: this is far from true. There are numerous roles in tech that do not involve coding – business analysis, project management, product management, marketing and procurement, to name a few.

- ‘Technology is boring’: tech is evolving at an exponential rate and it is considered hard to keep up with all the changes – that’s hardly dull and boring! Technology and digital can now be applied to almost all areas of our lives from our mobile phones (virtual assistants that are voice activated) to the computers that run and monitor our cars. They can complement many interests by providing new tools to address challenges and improve performance.

- ‘Technologists are nerds that work in cubicles’: nowadays most people work in agile teams in open-plan offices and workspaces. Collaborative workspaces are often the most trendy and cool places to work. The pandemic has shown many companies that they can operate successfully with their staff working from home; as they look to the future, many are considering a hybrid of remote working and the office, which will provide more flexibility for working parents.

- ‘Girls don’t like technology’: recently, several organisations (e.g. Code First Girls, Girls Who Code and Stemettes) have sprung up to provide tech programmes and initiatives for girls of different ages, ethnicities and communities because of their love of tech.

- ‘Girls are bad at science and maths’: there is no evidence to say that one gender is better at science or maths than the other. A study from the WISE (Women Into Science and Engineering) Campaign (2019) shows that girls are continuing to outperform boys in the majority of STEM subjects, with 67% of girls achieving A*–C (9–4) grades compared to 63% of boys. Further details on girls and qualifications can be found in Chapter 2, which discusses computing in schools in more detail.

- ‘STEM resources are available equally to girls and boys, [so] why don’t girls use them?’: different genders tend to learn in different ways, so the way the subject is taught in schools could determine why there is a difference. Boys tend to learn better when they have pictures, graphics and physical movement to help them grasp concepts whereas girls often benefit from the opportunity to talk about how to solve a problem and work with others on a solution. Fine (2010, pp. 112–115) however, challenges the idea that men and women are hardwired with different interests and argues that social and environmental factors strongly influence the mind. Therefore, schools need to find different ways to engage girls and boys with STEM resources.

- ‘Schools already offer tech classes’: sadly, the past IT and computing curricula in schools were lacking in engaging content for both girls and boys. Often, students were assessed on the basics, which were not interesting, especially for Generation Z, who are already digitally literate. Over more recent years the curriculum has changed significantly (see Chapter 2); however, the impact has not been as positive as was hoped.

- ‘Girls can just join the robotics course with the boys’: Welson-Rossman’s (2018) research found girls generally are not interested in a single discipline; they are looking for a variety of tech stimuli. This is exacerbated by the lack of variety in after-school technology programmes.

- ‘Girls only need women technologists as mentors’: yes, girls thrive with women mentors, but they need male mentors too, firstly because there are not enough female mentors to go around and secondly because they will benefit from getting a male perspective.

- ‘Women do not have the stamina for a career in tech’: science suggests that women have significant potential for physical and mental stamina, as seen in childbirth. So, the implication that women do not have the resilience to work in tech could be seen as a societal way of discouraging girls from even considering such career options. We need to show them the possibilities and help them to find their place within the community, so they can shine for others to follow.

Debunking these myths will allow more girls to consider a career in tech, feed the talent pipeline and enable organisations to create a diverse and inclusive workforce and environment where everyone feels trusted and valued. Organisations can help to disperse the myths by working with schools and highlighting role models.

ADVERTISING AND JOB DESCRIPTIONS

The attraction of talent starts way before candidates apply for a role that you advertise. The internet and the explosion of social media over the last decade mean that potential candidates can easily find out what you are doing as an organisation, who works there and what you can offer them.

Job descriptions

Women and men find jobs differently so designing your job description carefully is essential if you want to attract a diverse candidate pool. A report on gender by LinkedIn discovered that although women and men explored opportunities similarly, women were more selective when applying for roles (Tockey and Ignatova, 2019). It found that 68% of women (58% men) considered salary and benefits the most important factors on the job description. Therefore, when companies include these in their job posting, it indicates they are more likely to be committed to transparency and fair pay. Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In (2013) quotes past research indicating that the reason women do not apply is a lack of confidence; however, this is now disputed. Tara Mohr (2014) explains that the biggest reason for a discrepancy between women and men applying for a role (21.6% women vs. 12.7% men) was because the women believed they would not be hired as they did not meet the required qualifications, so they avoided rejection by not applying. The Behavioural Insights Team states that other reasons include risk aversion, requirement for flexible or part-time working, masculine culture depicted by the wording of job descriptions, and women potentially having less time due to other commitments (Hacohen and Nicks, 2019).

Job advertisements

Before you advertise a role, stop and think: ‘Is this advert going to attract all the candidates we want or just some of them?’ What do you need to do? Standard job descriptions may no longer be enticing or accessible to diverse talent; they might need to be revamped to be concise, specific and presented in an authentic and inclusive way that will attract applicants from various backgrounds.

Sheffield Digital surveyed its digital community to understand why people were not applying, and the message was loud and clear: ‘lose the aggression, drop the beer banter, be specific, honest and open-minded. The words and phrases you use have the power to inspire and enthuse, but they can just as easily tell a person that they aren’t welcome’ (Fletcher, 2020).

It is important to get how you convey your messages to future talent right on all communication channels, as getting this wrong could lessen your opportunities to improve your business. Talking about your organisation’s culture as ‘work hard, play hard’ or referring to ‘regular after-work drinks’ can cause people to doubt whether your organisation is the place for them, as they may question whether they will fit in, especially if they have busy home lives or do not drink alcohol.

Varied industry experiences can be good, as they bring diversity of thought. Start searching and advertising in different sectors and express that you want people with alternative perspectives to join your team.

Gaucher and colleagues (2011) analysed more than 4,000 job adverts and found that the use of gender-based words can be off-putting and dissuade female applicants. When masculine-worded advertisements were used, fewer women applied. However, the reverse is not true. While more women applied to feminine-worded advertisements, this did not reduce the number of men applying. This research also shows that if you are mainly receiving male applicants for your advertised roles then it is likely that the language you are using is biased towards one gender more than you may have realised. Unconsciously, we use language that is subtly ‘gender-coded’ because of societal expectations about how men and women behave. For example, women are often described as ‘bossy’ but men are rarely defined in this way; they are considered ‘decisive’. Table 6.1 gives some more examples.

Table 6.1 Gender-coded words used in job adverts

Masculine words | Gender-neutral words |

strong | able, proven, exceptional, excellent, solid |

ambitious | committed, dependable, cooperative |

driven | passionate, inspired, energised, motivated |

competitive | collaborative, results-oriented, enthusiastic, comparative |

principles | values, beliefs, benefits, practices, standards |

The WISE Campaign’s (2018) report on decoding job adverts highlights how we use gender-coded language without realising it. Additionally, adverts can include gendered pronouns and unnecessary superlatives. Ensure you swap gendered pronouns for gender-neutral ones (they/them/theirs) and remove the superlatives as either could deter suitable candidates. The WISE report provides an example of how you could change your advertisement to make it more appealing to a larger talent pool, as shown in Table 6.2.

Table 6.2 Gender-decoding your job adverts (Courtesy of the WISE Campaign)

Before | WISE Recommendation |

Manages the successful resolution of client issues, including competing demands, sensitive situations and conflicts with other groups. | Thoughtfully works things through with clients to resolve issues, including competing demands, sensitive situations and conflicts with other groups. |

Mobilises the team, establishing tactical plans, projects and objectives needed to accomplish these goals and ensure their attainment. | Mobilises and encourages the team, establishing the day to day plans, projects and objectives needed. |

Proactively manages the talent in their area, establishing performance goals and objectives, providing ongoing constructive feedback and establishing and implementing development plans. | Proactively nurtures the talent in their area, co-constructing performance goal, objectives and development plans and providing ongoing constructive performance feedback. |

Manages and resolves the diverse perspectives of stakeholders. | Is sensitive to the diverse perspectives of stakeholders and works with them to resolve differences. |

This linguistic gender-coding that appears in job descriptions puts women off applying for roles with masculine-coded language. To address the hidden implications of these biases, it is recommended that you use a recognised gender decoder to help create a gender-neutral and inclusive job description and advert. When gender-neutral words are used, women are more likely to believe they could carry out the advertised role. Murray (2018) mentions tools such as Textio and Gender Decoder, which can help to remove these biases.

Research from Textio shows that when advertisements include a well-defined equal employment opportunity (EEO) statement, jobs are filled 10% quicker than when an EEO is not included (Snyder, 2016). However, you need to state why you support the EEO and how it affects your company culture for it to have this impact. Explain why you embrace the EEO, diversity and inclusion, and also how you are committed and what outcomes you are intending to achieve.

As well as avoiding using militaristic words (e.g. salespeople may be known as ‘hunters’ and adverts may refer to ‘targets’ rather than ‘objectives’) and extreme modifiers (e.g. ‘amazing’, ‘excellent’, ‘terrible’), avoid using long bulleted lists of responsibilities and qualifications in adverts. Simplify your job descriptions. As Mohr’s (2014) research shows, people are less likely to apply for a role if they do not meet the qualifications required. If applicants don’t need a PhD to do the job, don’t include it! These findings suggest that women often see a list of job qualifications as a hard-bound set of requirements they need to meet, rather than employer preferences. This also applies to foreign languages and technical skills – leave them out if they are not essential.

Similarly, a report on LinkedIn analysed billions of data points on companies’ and candidates’ interactions and discovered that gender affects the candidate journey (Tockey and Ignatova, 2019). The results showed that while women and men explore opportunities similarly, there is a clear gap in how they apply for jobs. Women are 16% less likely to apply for a job after viewing it, 26% less likely to ask for a referral and 16% more likely to get hired for the roles they apply for. This data provides evidence that women are more likely than men to deselect themselves from applying after viewing a job description. Therefore, to encourage women to apply, be thoughtful about the number of requirements you list and ask yourself what is absolutely necessary. Women tend to apply for less-senior positions, going for ones that are a safer bet and hence offer a better chance of success.

If your ‘required’ criteria are not absolutely required, try to present them with some flexibility as ‘nice-to-have’ traits. Keep this section short and be specific about what core competencies you require – you are trying to influence someone to apply, not scare them off. Outline the core responsibilities of the position in enough detail so candidates can understand the requirements and can determine whether they are qualified. Highlight the day-to-day activities of the position as this will enable candidates to appreciate the work environment and the activities they will be exposed to. This level of detail will help candidates to determine whether the role and organisation are a good fit, improving your chances of attracting the best candidates.

Deciding what to put into the job specification can be difficult, so consider discussing the role with someone who already does it and spend time identifying their daily, weekly and monthly tasks. Then list the top five competencies required for those tasks and ensure they are reflected in the job description. Include the key technical skills and soft skills, such as problem-solving and communication, and consider stating the personality traits that are envisioned for the person who is successfully hired.

Whether you are a large corporation or a small start-up, most industries use a suite of acronyms, buzzwords and terminology that an outsider will not know, so check and remove any unnecessary jargon – it can make candidates feel unqualified and exclude women and people from different socioeconomic backgrounds or age groups. Check that the advert matches the standard and complexity required for the role by using the Flesch reading standards (Flesch is used to assess how easily a piece of text can be understood and engaged with – the text is given a readability score based on sentence and word lengths; for more information see Readable, 2017).

Finally, it may sound obvious but ensure you review the job description for accuracy before you post it. Remember, this is likely to be a candidate’s first interaction with you as the hiring manager so attention to detail is key.

LEGAL MECHANISMS

Positive action is a range of measures that an employer can lawfully undertake to encourage and train people from under-represented groups to help them overcome disadvantages in competing with other applicants. It is fully described in the 2011 amendment to the 2010 Equality Act in the UK and is mirrored by the concept of affirmative action in the USA. There are also similar provisions across Europe.

Examples of positive action include:

- stating that the employer welcomes applications from a diverse group (e.g. they want to increase the diversity in their workforce to redress a balance);

- targeted advertising of jobs;

- challenging recruitment providers within the supply chain to offer a diverse slate of candidates;

- participating in careers fairs;

- holding open days.

It is important to note that the job is still given to the best candidate, regardless of whether they have a particular protected characteristic or not. See the preface for more detail on protected characteristics and Chapter 4 for more information on positive action.

MARKETING AND BRANDING

Getting your marketing and branding right is vital to successfully attracting diverse talent. Even if you do not currently have a role open for people to apply for, you need to start nurturing, connecting and developing future talent to feed your pipeline. If people know you care about your staff, then others further afield will hear as word gets around that your company could be a great place to work.

Develop your marketing and branding so it encourages women to see your organisation as a place they would like to work. With information easily accessible, decisions can be made in a swipe, so ensure your social media and website portray what the future could look like for your candidates.

Social media

Once you have outlined the role and the skills required, the next step is to identify where to find your pool of candidates, and this will be influenced by what you are looking for. Successful workforces have cultivated multigenerational, diverse teams that bring various skills, priorities and perspectives. Therefore, attracting and sourcing candidates requires different approaches for different age groups, and a recruitment strategy to attract the best talent. The sections above have discussed several ways to improve job descriptions and adverts. However, with the evolution of social media, this is no longer the sole effective way of attracting possible employees; you need to modify your engagement to satisfy diverse candidates. Doing this will require you to embrace digital and adjust your recruitment practices to allow you to connect with a diverse pool of candidates.

Research from PathMotion (2020) shows that one way to attract diverse candidates and demonstrate that your organisation cares about diversity and inclusion is to leverage your employees as advocates by getting them to share their real-life stories and experiences in videos. Storytelling prompts an empathetic response from candidates as it comes across as more authentic, allowing them to see and hear from current employees what a day in the life of someone in a similar role entails. It has been suggested that visuals have the added benefit of getting a message across 60,000 times faster than by text (3M, 2000) – a picture really is worth a thousand words. Nowadays, people are always in a hurry so if you can provide a succinct video job advert you are more likely to hook a potential candidate, plus it can be shared easily over social media, thus expanding your reach.

It is key to embrace all social media channels to attract talent as there has been a rise in social recruitment: professional networks (e.g. LinkedIn) are becoming the key place to post job vacancies and manage talent because of their reach and growth of active users. Therefore, companies that are neglecting other social media platforms (such as Facebook, Instagram and Twitter) are potentially missing out on opportunities to meet the most diverse range of candidates who use different media.

In the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, many companies are having to look at different ways to attract and connect with talent pools. Apprenticeship and graduate recruitment are now conducted online, and this can provide a great opportunity to showcase your diverse talent and employees, and give students an opportunity to ask questions and see who really works at your company. They will be looking for role models and evidence that you are truly a diverse and inclusive company that they may want to work for. Remember, it’s a two-way process: they must like you as much as you like them, so you need to connect with them and engage them.

Websites

It is not enough just to post a job – you need to consider the way you promote diversity, inclusion, equity, sense of belonging and your organisational culture. Organisations that are outspoken about diversity and inclusion and that showcase role models are more attractive, particularly to diverse candidates, as this demonstrates they are committed to practising diversity and more likely to offer an inclusive workplace – it’s not just part of the company branding. Mention your diversity policy and ensure that pictures of diverse populations appear on your website. LinkedIn suggests employers that post more about diversity get 26% more applications from women (Lewis, 2020).

Look at your organisation’s website through a diversity lens. If you are stating that you are a diverse organisation yet the images on your website show men carrying out tech roles and women covering call centre roles, your audience will not believe you are being authentic. If your board or the tech team are all (or predominantly) male, you need to accept this will have a detrimental impact on your ability to attract women. However, you can state what your targets are on your website – for example, ‘30% women on the board by ‘20XX’. This shows positive intent and you can expand on how you plan to go about achieving these targets.

WHERE AND HOW TO FIND DIVERSE CANDIDATES

This section looks at where you can source candidates and how building relationships with potential candidates can help you to attract women and build your future pipeline. It explores traditional careers fairs and recruitment events; returner programmes and upskilling; schools and universities; graduate schemes, intern schemes and scholarships; external mentoring; community outreach; and other places and ways to find diverse candidates.

Careers fairs and recruitment events

Careers fairs provide organisations with an opportunity to connect with a talent pool from unique backgrounds and with a range of experience, as well as non-traditional candidates. Fairs enable organisations to showcase their diverse talent and allow space to discuss their open roles, culture and hiring processes, which can increase your brand awareness. Make use of both university job fairs and non-university recruitment events as this will increase your exposure to potential candidates. Often, job fairs are aimed at a specific target audience (e.g. women in STEM or women in tech), and hiring events may be targeted at specific roles, such as developers, architects or data scientists.

Virtual careers fairs and recruitment events are rapidly becoming the new norm while employee referral schemes can help to attract diverse talent based on recommendations and experience. Today’s candidates are looking to gain more insight into roles, employees and organisations. Virtual careers fairs are an easy way for candidates and organisations to interact without the limitations of location and budget. They enable organisations to bring their culture, values and behaviours to life. With most technologists working from home during the COVID-19 lockdowns, it has been demonstrated that people can operate effectively and efficiently from anywhere, which means with this mindset change it is now easier to consider your candidate pool as being global.

The power of live events is that they allow you to see more candidates, connect with them and get your key messages across; however, the connection needs to be interactive. Ensure you allow time for questions and answers, and consider running polls throughout the session to gauge how the event is going and to see how you could improve next time. There are several interactive audience tools available that can be used virtually and in person, such as Slido and Mentimeter, which poll participants and let you show the results live with real-time graphs and charts, and Catchbox, which is a throwable wireless microphone (for more suggestions, see Eventbrite, 2019).

Returners and upskilling

Mid-career and returner candidates may need to look at upskilling and how they market their transferrable skills. A person returning from maternity or caregiving leave will have gained project management skills that can be applied in the technology field and could fill current skills gaps within the tech industry. Equally, someone mid-career wanting to retrain having worked in a different industry will have complementary and transferrable skills. Either way, retraining can ensure you fill your vacancies quicker. Open roles have monetary and non-monetary costs associated with them. While roles remain unfilled, your current employees are impacted, as often they have the additional pressures of an increased workload. Prolonged periods of increased pressure could affect mental wellbeing, leading to stress, burnout and absenteeism, which in turn has a monetary value.

If women who left the industry for a career break and those looking for a new challenge were retrained, then the skills gap and lack of diversity in technology could be addressed and help to balance gender equality in the workplace. This group provide experience and skills that early career candidates may not have. They can reframe and apply their skills in different ways. The WISE Campaign (2020) emphasises how returner and retraining programmes are key to closing the gender gap in tech. Some companies that offer these schemes have seen an increase in the number of applicants per role, and WISE recommends several returner programmes that organisations can sign up to.

TechUK (n.d.) and WeAreTechWomen (n.d.) suggest other returner retraining programmes that can help to fill the gender gap and reskill talent. These programmes help to place upskilled candidates into roles in other companies while supporting them for the first couple of years. Look for ways to showcase people who have been through such programmes and retrained, and highlight where the skills gaps are.

Writing in The Guardian, Helena Pozniak (2020) states that according to the CBI (Confederation of British Industry), in late 2020 there were an estimated 600,000 vacancies in digital, and a lack of tech knowledge is costing the UK £63 billion each year. Women are discovering that there are roles in tech that do not require maths or a tech background, and they do not need to reinvent or retrain themselves. Examples include digital marketers, project managers, customer experience specialists and sales representatives. Signposting and showing how people can make the transition to your organisation will attract a new talent pool. This is reinforced by a survey conducted by HP in which 45% of women expressed a willingness to retrain into a technical role (see Ismail, 2019). Retraining schemes can be mutually beneficial, offering women opportunities to learn new skills and enabling organisations to fill open roles more quickly and close a skills gap.

Women are the biggest consumers of mobile gaming (Zenn, 2018), taking into consideration the people who play and the duration (60% women vs 47% men play daily). This ratio is believed to be growing, yet women are under-represented in designing and building these apps. For this reason, when seeking applicants, look at how you highlight your diverse talent and how science, technology, engineering, arts and maths (STEAM) skills could be applied to digital and technical roles. Also consider that broader disciplines will also have significant inputs in the creation of technology:

- art and graphic design: graphical interfaces, animation and user experience;

- biology and chemistry: analytical skills;

- physics and maths: algorithmic modelling, coding;

- philosophy and law: computer ethics;

- business: sales and marketing of technology.

Most returner schemes recruit women straight into their organisations. However, FDM recruits candidates, puts them on a seven-week training programme and then places them with industry-leading clients (FDM, 2021). The following case study provides further detail.

Case study: FDM Returners Programme

FDM Group is an industry pioneer when it comes to creating a socially balanced and gender-inclusive workforce. Guided by chief operating officer Sheila Flavell CBE, FDM specialises in attracting, educating and supporting female talent – its current median gender pay gap sits at negative 2.1 and the company regularly champions, places and supports women in STEM careers.

One of FDM’s flagship schemes is its Returners Programme, which provides both men and women with the opportunity to step back into a rewarding and successful career following an extended break. Whether it has been one year or 20, the Returners Programme is dedicated to supporting professionals on their journey back into work.

Sheila says:

Our renowned Returners Programme refreshes and expands on the returners’ existing skill set, ensuring they feel fully confident to re-enter the workplace. After seven weeks of training, the candidates are placed with one of our industry-leading clients to work as part of their team. Candidates are regularly deployed onto leading edge digital transformation projects, cloud computing, data migration, software development, or delivering business process improvements.

We also provide FDM consultants with comprehensive support throughout and beyond the Returners Programme. Our expert teams, many of whom are returners themselves, understand how daunting it can be when looking to return after an extended break and will guide them throughout the entire process. Our support initiatives include wellbeing and mentoring programmes, as well as flexible working arrangements during the training period should they be required. We are here to help all career returners transition swiftly and confidently back to the working world.

Case study developed with the assistance of Sheila Flavell CBE

Schools and universities

To attract talent, you need a pipeline, so start creating links with your local communities and schools, and look at mentoring girls and getting them to come to your offices and meet women so they can discover what roles they do. There are a number of not-for-profit organisations that run programmes that can help build these connections. Organisations such as Stemettes, Apps for Good, the Raspberry Pi Foundation, Code First Girls and TeenTech can help you get started (see Table 6.3 for a more comprehensive list). Engaging school children in your communities can help them to see the possibilities in STEAM through fun and exciting learning experiences, which can help to build a pipeline of talent and start an early connection between you and them.

Table 6.3 Not-for-profit organisations that can help to build a diverse talent pipeline

Organisation | Website |

Apps for Good | |

BCSWomen | |

Business in the Community | |

Code Club | |

Code First Girls | |

Computing At School | |

Girls Who Code | |

Modern Muse | |

Mosaic Network | |

National Autistic Society | |

Prince’s Trust | |

Raspberry Pi Foundation | |

STEM Ambassadors | https://www.stem.org.uk/stem-ambassadors/find-a-stem-ambassador |

Stemettes | |

Stonewall | |

Tech For Good | |

Tech Talent Charter | |

TeenTech | |

WISE Campaign |

HRH The Prince of Wales champions responsible business. One of his schemes is Business in the Community (BITC), which works with businesses to support young people in schools facing disadvantage by forming long-term strategic partnerships using its Business Class framework (see Business in the Community, 2021). BITC also connects with businesses that want to publicly demonstrate a commitment to acting responsibly and investing in building a better society. This enables business leaders to share their skills and enables organisations to prepare people for the workplace.

Another organisation, the Prince’s Trust, supports the Mosaic Mentoring Programme, which ‘inspires young people from deprived communities to realise their talents and full potential, through the power of positive relatable role models’ (Mosaic, 2021). The scheme empowers young people with confidence and self-belief. Building these strong partnerships between your organisation and local schools can have a positive impact on the children you work with; Mosaic showed that if a child goes to a workplace three times, they start to believe they can work there and do a job like their mentors.

Think about running events with organisations such as Stemettes, whose aim is to show the next generation of girls that they can do science, technology, engineering and maths. Another example is Girls Who Code, whose mission is to close the gender gap in technology and to change the image of what a programmer looks like and does. Alternatively, get your female staff involved with online mentoring programmes for young women such as Modern Muse. These are just a few suggestions for how you can illustrate your commitment to gender equality, diversity and inclusion and can start to attract young female talent into your pipeline. If you are planning to hire apprentices, it is a great way to engage them early and develop the relationship between your community and your organisation.

Graduate schemes, intern schemes and scholarships

Graduate and intern schemes can be great ways to attract female talent. However, if you want to attract diverse talent, you need to take a diverse team with you. People need to see people like them to consider applying to your schemes. An example is the WISE Campaign (2021), whose My Skills My Life project (which evolved from People Like Me) aims to engage more girls to consider studies and careers in STEM.

When you bring your interns and graduates into your organisation, ensure you enable them to meet people in different roles throughout the different levels of your organisation. Most of all, give them an experience they will remember positively; don’t just give them jobs no one else wants to do – if you don’t want to do them, they probably won’t either and consequently won’t be impressed or inspired to work for you. Remember that a single negative experience can spread quickly on social media.

Finally, consider creating internships and scholarships specifically for people from under-represented groups and contact schools, colleges and universities to help promote your offerings. Question what skills you need and whether formal qualifications are really a requirement for the role: could you take on an apprentice or recruit someone from a non-traditional or non-academic route? It is not always necessary to have an IT degree with a 2:1.

External mentoring

Mentoring involves investing time and sharing expertise to enhance another’s knowledge and skills. However, it does not just help your leaders grow their leadership skills; it also develops your mentees. Providing opportunities to mentor outside your organisation benefits your employees and also signals that you are serious about attracting diverse talent. Demonstrate your commitment and get involved with companies such as INvolve (2021), which works with businesses to drive positive and sustainable growth through inclusion. This company provides solutions to diversity and inclusion that are tailored specifically to your organisation’s needs. One of its schemes is a cross-industry global mentoring programme that brings diverse talent and senior business leaders from throughout its global network into mentoring partnerships. By fostering these types of relationships, you start to connect with people and demonstrate your organisation’s commitment to inclusion. You also gain opportunities to share best practice with other diversity and inclusion professionals.

Thoroughly embrace diversity and you will get a team with different perspectives, which encourages listening and understanding, and will ultimately contribute to the success of your team and organisation. This requires engagement at all levels and changes in attitudes to be successful. It is important for organisations to promote their engagement in current issues such as gender equality, inequalities and quality education. Several networks and not-for-profit organisations (such as BCSWomen) focus on inspiring female talent, linking women to organisations, running mentoring programmes, providing opportunities to meet like-minded people, offering opportunities to listen to high-profile women talk about their career journeys or programmes they are working on, and organising other events. Engaging with these types of networks can inspire your female staff and attract new talent.

Case study: 3Squared

3Squared is an award-winning technology solutions and service partner dedicated to using its knowledge and expertise to deliver technological solutions to known and emerging transport industry challenges. It is trying to create a diverse and inclusive workplace.

There is a serious skills shortage in engineering, and it is crucial the rail industry plugs the widening science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) learning skills gap if it is to meet the transportation needs of the future. All sectors must work together to inspire young people to pursue careers in STEM.

Cherry Limb, HR manager at 3Squared, explains:

The rail industry is still facing a lack of diversity and gender imbalance. If businesses keep hiring from the same pool, they won’t be able to tap into a wider range of talent. The industry must encourage more females and other under-represented groups to study STEM subjects if it is to access a greater range of expertise. Although we are above the industry average with around 25% women generally within our organisation (with a 50:50 split on the directors board and 58% women at operational management level), it’s not enough – there’s always more we can all do.

What are you doing to address these challenges?

Cherry says:

We look at different ways to attract talent through multiple channels: recruitment agencies, job boards and employee referral schemes. We sponsor or speak at local group meetups such as Dot Net Sheffield (https://dotnetsheff.co.uk) and Sheffield Women in Tech (https://shfwit.org) and we are also a disability positive employer.

We are ensuring our policies, language and values are designed to attract diverse candidates to apply and that these are reflected on our website and communication channels. We state on our website that we are not a box-ticking organisation and that we offer training where needed and we encourage people to get in touch to discuss each role. We demonstrate transparency with testimonials about what it’s like to work at 3Squared, flexible working, support with training and culture. We have ensured all our line managers have undergone unconscious bias, cultural intelligence and emotional intelligence training. We always run our job advertisements through a language checker to identify wording that may put off female candidates, carry out blind screening of the candidates’ CVs and monitor the diversity of the applications we receive.

We run internships programmes, offer work experience, host talks at colleges and universities, and strive to promote an inclusive and diverse workplace. By showing the younger generations what’s possible and how STEM subjects can be applied to tech, we help to open up avenues they hadn’t previously discovered. Science encourages research and analysis. Technology-savvy people are at a great advantage to make changes and improve current situations. Engineering is about building and producing, and mathematics affects everyday life, such as making decisions based on comparative information.

We are collaborating and partnering with other local companies such as Sero HE and school children between 13 and 15 years to get the next generation of workers by raising their awareness of the opportunities out there. Showcasing role models illustrates the art of the possible, whether the role model is a coder, technical architect, project manager, or someone whose role involves supporting tech, such as HR or finance.

There is a job in tech for everyone.

Case study developed with the assistance of Cherry Limb

Other groups

Widen your search by investigating how you can reach diverse candidates by contacting charities that can connect you with inclusive employers and agencies. For example, the National Autistic Society (2021) has an Autism at Work Programme and Stonewall (2021) can tell you which companies have workplaces where LGBT+ employees are ‘accepted without exception’. Other talent pools to consider are ex-military and people with disabilities. Posting your job specs on niche job boards or working with specialist agencies will improve your chances of hiring diverse talent, not only women.

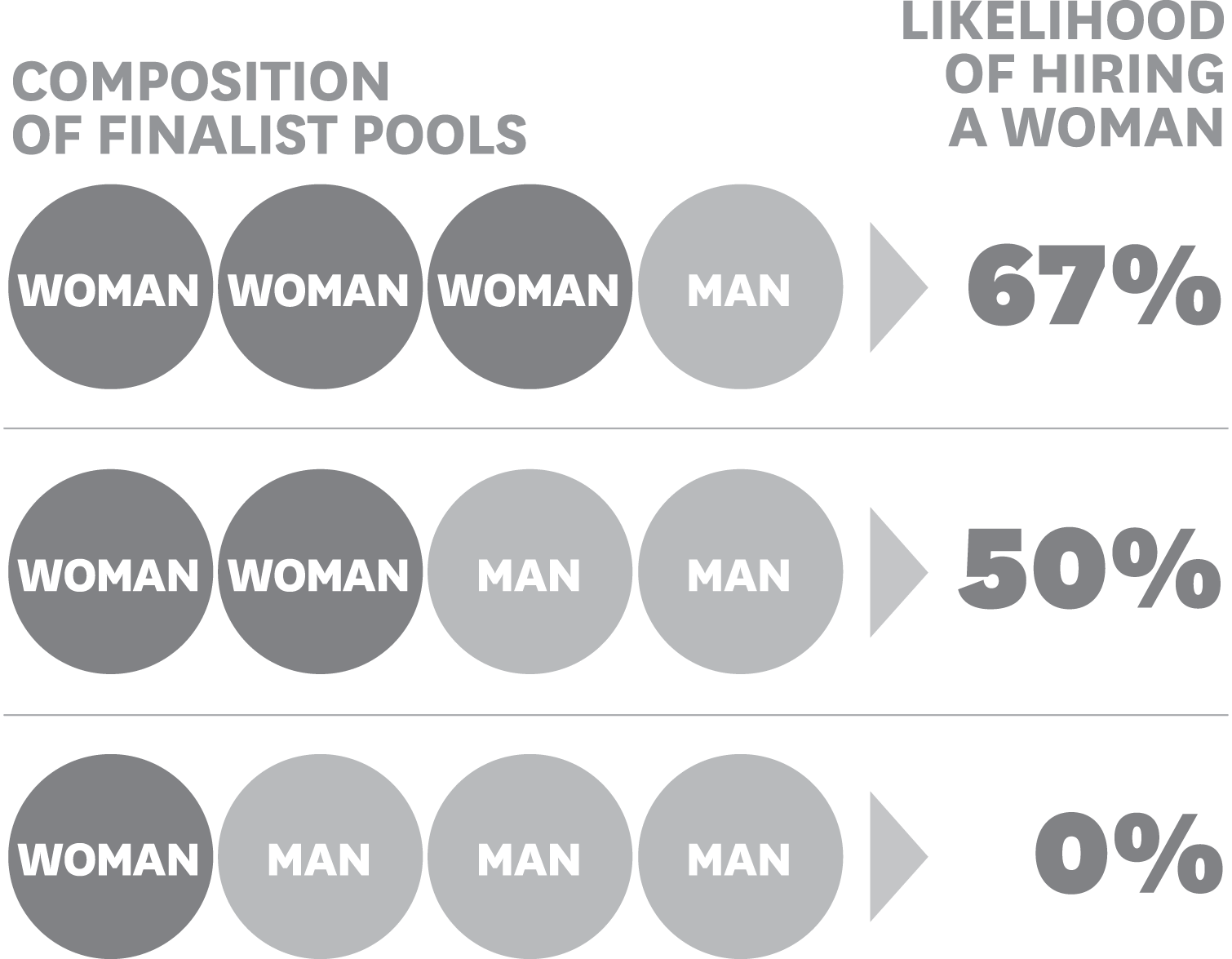

The truth is that it takes time to find talent at all levels of an organisation, and finding diverse talent can take longer. Sifting through CVs to ensure you have a gender-balanced shortlist is time-consuming as it may require you to push back to agencies asking them to find you more female candidates. If they say they have not got any, state you won’t be taking any of their candidates forward to interview until they provide an even pool. Sadly, when time pressure is high, people have the tendency to fall back on the ‘safe’ (stereotypical) bet, so a commitment needs to be made even in times of high pressure. What helps here is setting expectations about timings with hiring managers.

Case study: Hampton-Alexander

Hampton-Alexander (2021) has been instrumental in improving the gender balance in the FTSE leadership. Its review set a minimum 33% target for women on all FTSE boards and in executive leadership positions by the end of 2020. Annually, it lists the performance of the FTSE 100, FTSE 250 and FTSE 350 firms against these criteria, calling out successes and failures. This has been successful in driving change in this group of firms, with the average numbers of women on the boards of these companies exceeding the target in October 2020: 36.2% in the FTSE 100, 33.2% in the FTSE 250 and 34.3% in the FTSE 350. However, as of 2020 the percentage of women in FTSE 250 executive leadership was still below target at 21.7%, showing there is still a long way to go. This could be a challenge because the more senior the position, the longer it will inevitably take to recruit.

THE OFFER

The line manager and HR manager must have a clear understanding of the recruitment package’s components and what women are going to be looking for in a role.

The Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) (2020) states that a strong employer brand should connect the organisation’s culture, values, people strategy, policies and ethical standards. In times of economic uncertainty, organisations can use their brand to compete effectively by attracting, recruiting and engaging talent. Key to this is the employee value proposition (EVP), which is a unique set of benefits the employee receives in return for their skills, capabilities and experience. It includes why people are proud and inspired to work for the company. The EVP provides the foundation for attracting the best external talent, so failure to make your EVP compelling will cause the other interventions to underdeliver. It is therefore imperative that you understand why potential employees will be attracted to your company and appreciate why your existing employees stay, what their perceptions are and what they value most about working there. This knowledge will form the foundations of how to market your organisation during the recruitment process.

An employee value proposition to attract diverse talent

To stand out from the competition for talent, you need to be able to offer something unique, and a strong EVP will facilitate your recruitment and talent acquisition strategies. A potential candidate can offer values such as experience, technical skills, management and personality to an employer, and in return they offer pay, growth opportunities, career development, culture, training and benefits.

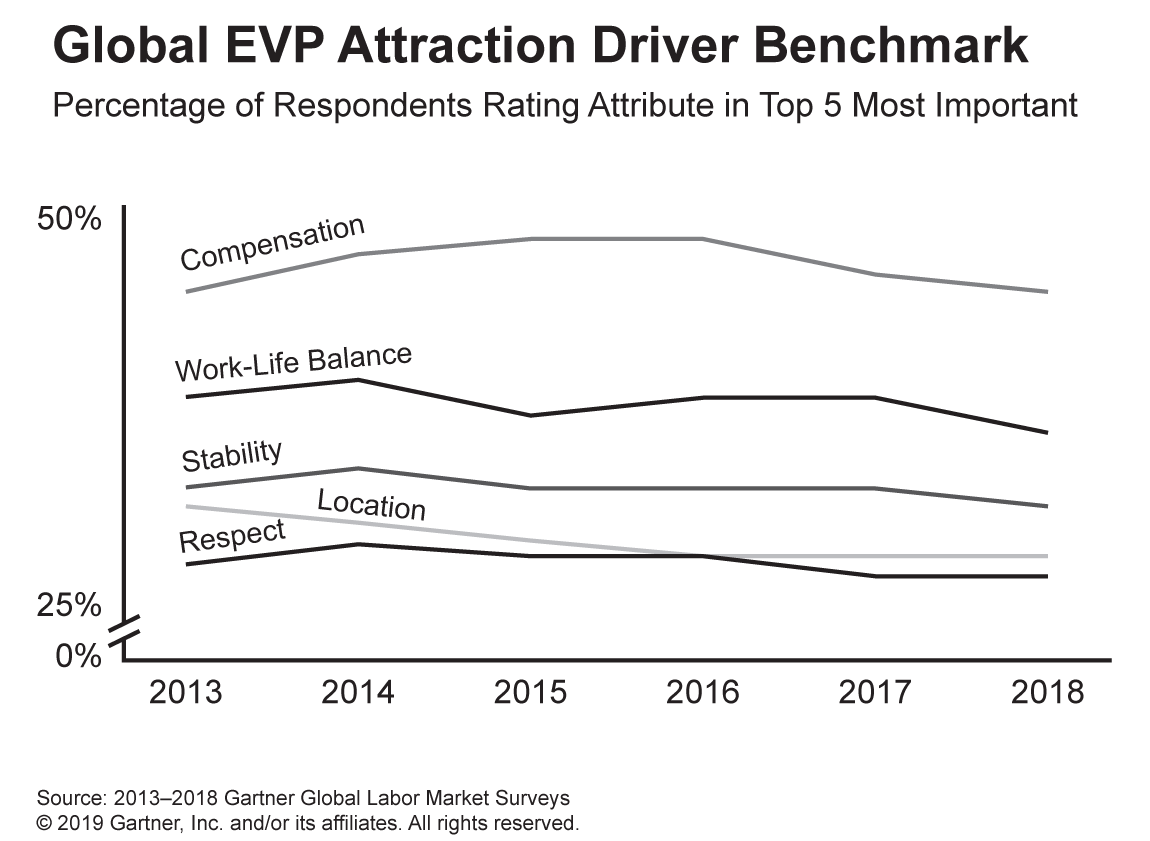

The five fundamental elements of the EVP are compensation, work–life balance, stability, location and respect. These form part of your employer brand. Figure 6.1 shows the percentages of respondents that placed each of these five attributes in the top five in importance, according to Gartner.

Your EVP will help to differentiate you from your competitors by appealing to your candidates’ values, beliefs, needs and wants. Gartner (2021) states that ‘organizations that effectively deliver on their EVP can decrease annual employee turnover by just under 70% and increase new hire commitment by nearly 30%’. Use these attributes to promote your EVP, so prospective talent can see the benefits and value of joining your company.

Figure 6.1 Global EVP attraction driver benchmark (Courtesy of Gartner, https://www.gartner.com.au/en/human-resources/insights/employee-value-proposition)

Knowing what your current and future employees want and value is the foundation of a successful EVP. Think about developing a clear and catchy EVP statement that you can use on social media so talented people are attracted and understand the workplace experience they will get – for example, Canva’s EVP is ‘Be a force for good’, Merck’s is ‘Invest. Impact. Inspire’ and Honeywell’s is ‘You can make a difference by helping to build a smarter, safer and more sustainable world.’

However, while these may attract candidates initially, they will also expect to see good, substantiated material describing what it is like to work for you on your website. This should be reinforced in interviews, repeated by people who work for you, and reconfirmed and written about in blogs and on sites such as Glassdoor.

Equitable practices

Equitable practices (pay equity, acknowledging holidays for all cultures, ongoing feedback, recognition and managing biases) help to close the gap for all employees and organisations with the benefit of gaining competitive advantage from building diverse talent. Promoting your metrics relating to equity will provide a clear indication of how your organisation operates. These metrics are a great way to demonstrate your commitments and should be included in your marketing and branding. Once you understand your data, set targets for what you want to achieve and how. In the past, organisations looked to attract and recruit people who were a good cultural fit; however, more progressive companies are trying to attract talent on the basis of cultural contribution. This means hiring employees who align with your organisation’s values but also bring their diverse cultures, experiences and backgrounds to the table.

There is not a single strategy that organisations can apply to instantly create gender equality in the workforce, which means it is necessary to implement different strategies for new starters, first jobbers (young people newly out of education), returns and senior hires. Some key strategies for attracting women follow. These are ways in which employers can adopt an inclusive workplace model and demonstrate that diversity is a priority:

- ensure equal pay;

- provide opportunities for growth;

- offer employee benefits that are sensitive to women’s needs;

- recognise women’s achievements at all levels in the workplace;

- provide coaching and courses that support female employees;

- make a commitment to diversity and inclusion that extends beyond gender;

- ensure support for families and work–life balance;

- offer flexible working;

- provide high-level purpose.

Shocking statistics show that even several decades after the Equal Pay Act was passed in 1970, women still only earn 81p for every pound earned by men, and on average earn 52% of what men do every year, as often they sacrifice the opportunity to earn a wage to support their families (Women’s Equality Party, 2021). While these are general figures, they are reflected by women working in tech.

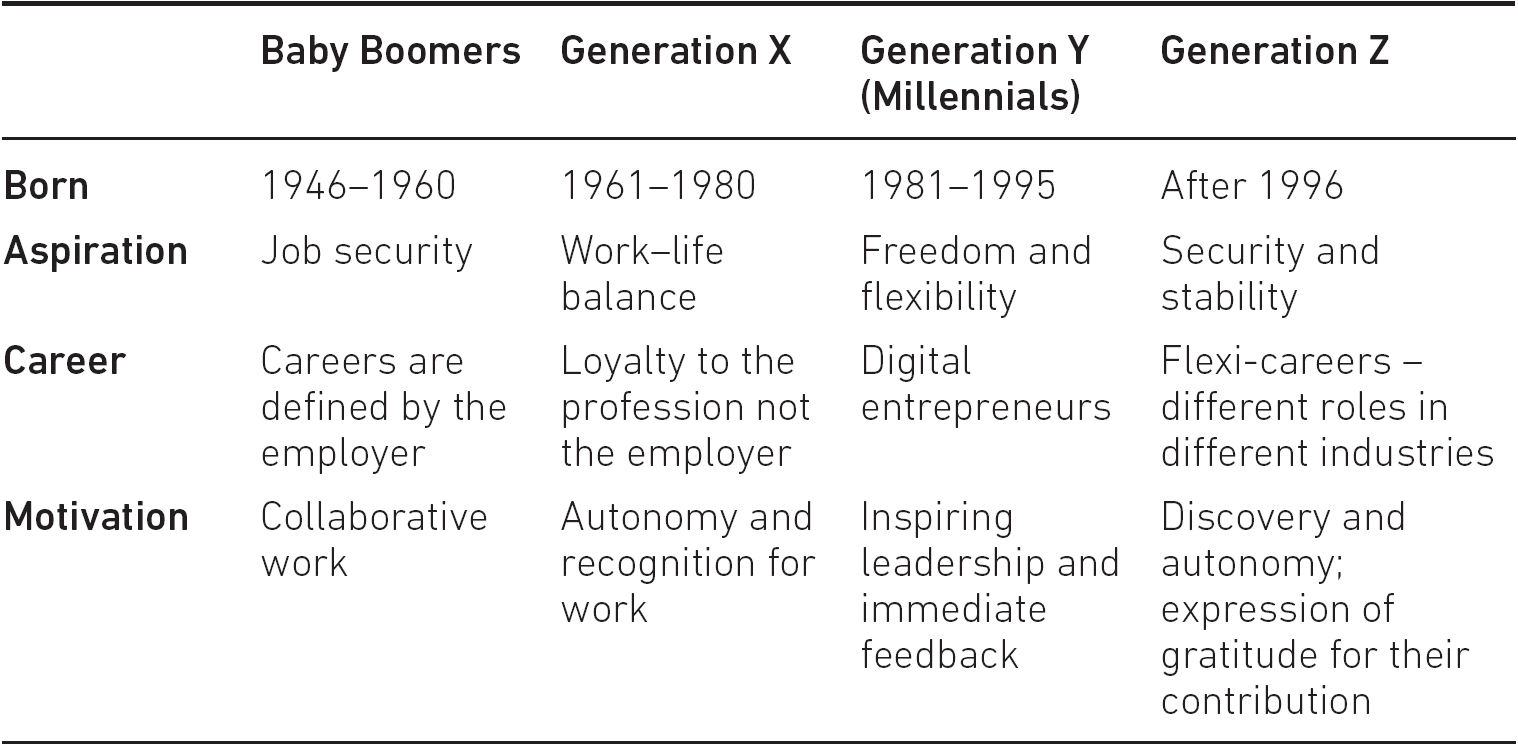

With four generations (Baby Boomers and Generations X, Y and Z) currently in the workforce, you need to appreciate their defining features, what their drivers and sense of purpose are, and how you can win their hearts. Each generation brings something uniquely valuable to the workforce and has different motivations. By understanding what they bring to your team or organisation, you can identify what development and training they may require and how they may wish to be rewarded. Therefore, you need to have flexible, equitable practices to attract them. Table 6.4 outlines some of the differences between the generations.

Women candidates from Generation Z bring different skills, expectations and ambitions to the workplace than women in earlier generations, as most of them are digitally native and will have learned coding in school. Further details of such coding schemes can be found in Chapter 2.

Allyship

Another way to demonstrate your commitment to gender equality is to show how male allies are engaged in your employee resource groups. An article in Harvard Business Review shows that when men are deliberately engaged in gender inclusion programmes, 96% of organisations see progress, compared to only 30% when they are not (Johnson and Smith, 2018). Having male allies can help to attract, develop and retain women. One way to show dedication to male allyship is to sign up to the United Nations’ HeForShe movement,1 which aims to get people everywhere to understand and support the idea of gender equality and encourages men and all genders to stand in solidarity with women to create a united force for gender equality.

Talent programmes

Companies’ talent development activities form part of their EVP offering and these can be used to attract new candidates. Adopting diversity programmes that help women navigate the career ladder, honour employee’s religious and cultural practices, and offer training, mentoring and professional development schemes will help to make jobs appealing to women.

When attracting women for higher-level and C-suite roles, bear in mind that candidates will be looking for clear, transparent career ladders backed up by corporate training programmes. Having programmes that are designed and targeted to the development of women is appealing to female applicants so ensure you promote these externally.

Transparency

Be transparent about your salaries and gender pay gaps, and what you are doing to get to gender parity. In the UK, all firms with over 250 employees are mandated to report their gender pay gaps annually and include their reported figures on their website. An article in Time magazine reports that ‘employees want more information… There’s more information that’s available in the marketplace that’s accessible to employees and job candidates. If an organization doesn’t form its own pay method on transparency, someone else will – and it probably won’t be a complete message’ (Cooney, 2018). Therefore, control the information and messages you put into the public domain and be as transparent as you can, otherwise future employees will be investigating Glassdoor, PayScale or other websites to determine salaries and other feedback about your organisation.

By being transparent, you can show how the pay and reward approach supports your organisation’s vision and mission, and this is likely to start to build trust between applicant and employer. It allows a comparison and evaluation of the real situation and the current policies and practices, how they need to change and by when. Discussing and addressing any disparate pay issues shows commitment to gender parity.

Flexible working

The COVID-19 pandemic has shown that working from home is a viable option for most technologists. This has led to employers establishing flexible working schedules so parents and carers can home-school or conduct care activities, moving the focus to outcome-based delivery as opposed to presenteeism. Going forward, this is unlikely to change. Having flexibility will help to attract women to your organisation or back into the workplace, especially if they can mix being in the office and working from home. Generation X consider flexible working an important part of their working life so offering it will allow for a better work–life balance and a more supportive working culture.

Additionally, provide cover to support people to manage their family life by offering the option to buy additional annual leave, childcare vouchers, and onsite or nearby day care. Having flexibility in hours and location (such as working part time or during school hours) is key to attracting female talent. It is not just about start and end times, however; stipulating core times when people need to be available will help multigenerational workforces to adjust and be more productive. Remember, not everyone wants flexibility because they have children – they may want it because they are a carer, studying for self-development or volunteering to bring further purpose to their life. These changes not only help to attract women but can also benefit everyone who works within your organisation and consequently improve employee retention.

Parental leave

Don’t just offer maternity leave – include paternity leave in your benefits and display this as part of your gender equality commitment. Make it clear that parental leave can be split 50:50 between both parents. Including parental cover in your reward system can incentivise and attract women (and men) as it will make it easier for staff to return after a break.

Sponsorship

A workplace sponsor is different from a mentor as they tend to be someone who holds a senior position within a company. They help to guide and navigate the sponsored person through the complexities of the organisation and advancement politics. A sponsor will work with a high-potential individual and be a champion for them when they are not in the room. Sponsors go beyond general career feedback and advice.

Let your future talent know if sponsorship is part of your culture and part of your gender equality agenda. Sponsorship gives high performers great opportunities to excel, and this leads to job satisfaction, which can be reflected on scores on Glassdoor and consequently attract women to apply for positions. Catalyst (2011) supports this and states that effective sponsorship benefits organisations through more effective leadership, increased satisfaction and commitment among team members, and enhanced retention. It creates a culture of talent sustainability and fosters a ‘pay it forward’ attitude within the workforce.

According to the Chartered Management Institute (2019), 66% of people surveyed agreed that sponsorship for success supported gender diversity in the executive and leadership pipelines. Sponsorship also increases the number of advocates, and women who are sponsored are more likely to ask for a pay rise or promotion and get one. The institute recommends that (Chartered Management Institute, 2019, p. 3):

- ‘Sponsorship, alongside mentoring, must form part of a commitment to leadership gender diversity and be driven from the top.’

- ‘Formal sponsorship programmes need to be developed as part of structured talent management programmes to support gender progression in business.’

- ‘Businesses need to ensure a culture of sponsorship is embedded throughout the leadership layers, especially in large companies.’

- ‘Businesses should combine sponsorship efforts with a culture of, and structured approach toward, mentoring so women receive support all the way to the top executive roles.’

- ‘Senior women and men should act as agents of change to back formal sponsorship in organisations where such programmes are yet to be implemented.’

Making an offer to the successful candidate

You have identified the successful candidate so do not risk losing them! If you do let this happen, you will either be forced to take the next best candidate or even worse spend more time and money starting all over again. Top diverse talent is hard to find in the current candidate-led market. If they are interviewing with you, they are probably interviewing elsewhere, so if you want them for your organisation, do not hang around. Make them an offer before another company snaps them up. Sifting through CVs and setting up interviews can be timely pursuits so have a clear process and timeframe to follow as delays at these stages can also lose you candidates.

Clarify the timings with hiring authorities and candidates in terms of the candidate’s notice period, holidays and other commitments. You need to anticipate any other timing obstacles that could affect your ability to onboard them in a timely manner. In a competitive market it is worth knowing whether they are attending other interviews or are considering other offers.

How you make your job offer is crucial in ensuring you land your future employee. A job offer is an employer’s final incentive when it comes to attracting talent to the organisation. Failure to get this right could mean losing them to a competitor.

Phone the successful candidate as soon after their final interview as possible with the verbal offer and let them know how excited you are that they will be joining your team. Remember to convey your enthusiasm – you are still selling the job to them and building rapport between future employer and employee. Make the offer call memorable by explaining why you were impressed by their skills and experience. Remind them how you see them fitting into the team and the company culture.

Pay scales: Benchmarking and calibrating

The Equality and Human Rights Commission (2020) states that employees should be rewarded for achieving a set of competences, so you need to ensure that there are not any gender biases built into how these competences are assessed and that candidates have equal opportunities to demonstrate them. Calibrate your pay scales against the market rate for the role on offer in that location to ensure it is gender neutral. Benchmark your package and policies to ensure they are good enough to attract the top talent. Candidates will usually expect at least a 10% increase relative to their previous position plus enhanced benefits. Explain the components of the full package: salary, bonus schemes, pension, health cover, share schemes, and other benefits and perks.

Candidates will often attempt to negotiate their offer, so it is important to understand what they might do so as to be prepared to react to their requests, especially as men and women approach this area differently. Women may be less forceful, or less successful in their negotiations due to bias. The Government Equalities Office (2019) explains that women are less likely to negotiate their pay so employers should be clear and honest about what their organisation’s boundaries and constraints are for the reward package. This helps applicants to know what they can reasonably expect and, by clearly communicating the salary ranges on offer, opens up the possibility for women (and men) to negotiate their salary. An article in Harvard Business Review explains how many individuals focus on negotiating the salary rather than the whole deal (Malhotra, 2014), so be transparent about your pay, reward and promotion policies, and your process and criteria for decision-making, as this can reduce pay inequalities. To assist with the reward negotiations, hiring managers should be trained on what the allowable ranges are for each reward and they need to be aware of the gender differences; for example, women are often more interested in health cover as opposed to a company car scheme (PwC, 2015).

Ask the candidate what they think of the offer so you can anticipate whether there are likely to be any issues that may need to be dealt with later. In larger corporations this is likely to be handled by the HR team, who will negotiate the final package with the agency. Try to ascertain a verbal acceptance and explain what the next steps are and the timelines. For example, tell them how many days it will take to send them the official contract, and tell them how quickly you will need them to respond. The contract should contain all of the proposed terms of employment and enough information about the role and company to enable them to make an informed decision that joining your organisation is the right thing to do. Ideally, the decision should be in line with the candidate’s aspirations and motivations so as to ensure their engagement when they join.

Nurture your candidates before and after making the offer, through keeping in touch at each step of the process, thus reminding them of you and your interest in having them on the team. Consider inviting them in to meet the rest of the team and suggest that a team member becomes the new employee’s buddy, to help them with any questions before and after onboarding. Keep building connections and relationships, and perhaps offer to arrange for one of the senior women to be the new employee’s mentor. However, it can be equally rewarding for women to be mentored by senior men who act as allies; this can be hugely valuable to women throughout their careers and importantly start to break down the barriers and silos.

Candidates who leave the process early

Why are your preferred candidates dropping out of the process early, turning down your offers and accepting roles elsewhere? They are normally doing this because your recruitment processes are flawed. The main reasons cited by articles on Glassdoor and JobMonkey are low salary, poor perks, time taken between the interview and the offer, poor Glassdoor and other online reviews, weak employer brand, contract terms and cultural fit (Saldanha, 2019; JobMonkey, 2021).

The reasons vary depending on the age group of the workforce you are recruiting as different groups have different drivers; therefore, having a flexible benefits package that you can easily adapt will help you to win the best talent. Candidates are looking for opportunities to grow, learn and progress through an organisation, so if they cannot see these prospects they will look elsewhere. An article in Harvard Business Review found that people want three things from their work: a career, a community and a business cause (Golder et al., 2018). They value these over salary when deciding to work for a company. The career is about work: the person must have autonomy, the ability to use their strengths, and a chance to learn and develop while doing their job – these are intrinsic motivations. The community is about people: connection and belonging by being respected, recognised and cared about for the work they produce. The cause is the purpose: identifying with the organisation’s mission and values, making a meaningful impact and doing good in the world.

Generations Y and Z are more concerned about company culture than any other generation, so you need to show that you can provide an environment and culture people want to work in to secure top talent. The work environment needs to be one that is enjoyable, productive and fun, and where the candidate feels they fit. Part of the company’s culture is the EVP. An article published by McKinsey states that leaders who understand the power of the EVP and can indicate that it is stronger than their competitors’ can attract and retain the best talent (Keller and Meaney, 2017).

CREATING AN INCLUSIVE INTERVIEW PROCESS

This section shows how you can create an inclusive interview process and highlights how to approach potential challenges relating to conscious and unconscious biases that can occur throughout the interview process.

Biases can occur at all stages of the interview process, from selecting your interview panel to deciding your interview questions, evaluation methods and rating scales. Being aware makes it easier to ensure biases are minimised. This section provides an overview of unconscious bias and socialisation. However, the topic as a whole is discussed in more detail in Chapter 4.