This chapter explains the business case for a diverse workforce, specifically focusing on gender diversity within the technology profession. Before covering the essentials of the business case for diversity, it’s important to outline the history of the roles of women in the technology space and the long struggle to make inroads into the declining numbers. Currently, women make up around 17% of the UK technical workforce whereas they constitute almost 50% of the working-age population (BCS, 2020b). In a recent survey, BCS (2020a) asked survey respondents what they thought was the biggest diversity barrier to getting a first job in IT. Equal first place went to ‘gender’ and ‘age’, with 22% believing that these characteristics gave a disadvantage.

This has not always been the case. As we came through the ‘year 2000’ technical issues, the number of women in the technical workforce seemed to be a few percentage points higher, but they quickly declined. As explained below, this may have been due to changes in the way that the technical professions were counted during the late 1990s, or it might have been a disappointing fact. At this time, in the late 1990s, when many of us started working on projects to increase the gender diversity of the workforce, we thought that numbers over 20% were a poor showing, never realising that they would remain consistently at 17% female representation in the following years and stick at this very low level two decades on. It is hoped that the arguments laid out in this chapter will serve to convince those in authority, or those holding the purse strings, of the very real benefits of embracing diversity in IT.

THE HISTORY OF WOMEN IN TECHNOLOGY

Much has been written about Ada Lovelace (1815–1852) and her position as architect of the learned craft of coding. Many women in technical roles see her as a great role model, and, in the USA, Grace Hopper (1906–1992) is revered for her work, which led to the development of the programming language COBOL. What is patently obvious, though, is that women coders and IT professionals have been scarce since Lovelace became the first. We have very few from the last decades of the 20th century to put name to as role models for a new generation of IT workers.

This state of affairs might be attributable to the fact that women did not take up a breadth of science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) occupations in the UK until after the First World War. The propaganda, marketing and research that promoted the status of housewife and mother kept women ‘in their place’ for the decades up to the 1960s. There were notable exceptions, such as the ‘ENIAC Girls’ (named for their work on the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) and the women at Bletchley Park, but they were far from the norm, and where women did work, the majority held clerical or caring positions. Even the women of Bletchley Park saw a downgrading of their skills in the decades after the war effort; as their roles became part of the UK’s Civil Service, they were reconceived as clerical ones (Hicks, 2018). During the 1960s, as the perception of the work of ‘computing’ changed, the work was redefined as more professional and became a male domain. There were still roles for women, but, as Mar Hicks notes in Programmed Inequality (2018, ch. 1), they were marginalised and saw their male peers overtake them in seniority. There were, however, roles where women could fit in. Women working with typewriters for admin purposes could move easily into using the large card punch machines with the advent of mainframe-based commercial computing. As shown in Figure 1.1, the punch machines were fundamentally typewriters with card punch equipment strapped to the back.

Figure 1.1 IBM punch machine (Source: ‘IBM card punch station 029’ by waelder, from Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0)

Therefore, women transitioned seamlessly from secretarial careers to jobs in the punch room. In the UK certainly, when the modernisation of technology and the demise of the punched card meant redundancy for the punch machine, women moved on to become coders and experts in building applications in PL1 and COBOL. Punch room women whom I met in the mid-1970s were correcting code as they typed, so it was a natural move for them.

However, the early coding roles were seen as fairly low status, similar to the secretarial roles. Men were the hardware engineers, electronics engineers and telecom engineers. The rise of home computing in the 1980s and 1990s saw males use their leisure time to acquire an interest in coding and technology. With this shifting gender demographic interested in coding, the status of the profession rose and it became more exclusionary for women (Thompson, 2019).

The ex-punch-room women seemed to stay within the UK technical population as coders, but also in trusted roles in systems analysis and project management until the millennium bug had been cleared from business systems in the year 2000. It seems likely that the women who had originally worked in the industry in the punch rooms were ready to retire after the big push to get applications and systems through the turn of the century. This may have been part of the reason for an apparent decline in numbers in the early years of the millennium. That said, a reported peak in numbers around the year 2000 may never have been as high as was believed: while the numbers appeared to be a few percentage points higher around that time, it now seems more likely they were closer to 17%. The discrepancy seems likely to have resulted from changes to the government’s method of counting (i.e. the elimination of data entry people in the UK government’s Standard Occupational Classification 1990 system). The figures have remained the same, sadly, since this point, and have been virtually static, at around 17% women in the technical professions (BCS, 2020b).

As we go to press with this book, we are seeing reports, as covered in Chapter 3, that women are now making up a greater number of entrants to technical courses, which is really encouraging. Many of our own employers have run campaigns to attract and retain women in technology roles, giving us an understanding, which we can share, on what needs to be done. There has been so much effort from volunteers like us working in the technical professions, aiming to increase the numbers of women on technology courses and in the professions, that we would be horrified if there had been absolutely no progress. It remains to be seen which actions are really having good effect. We hope that progress will continue, but we know that there is still a long way to go to reach parity. We believe that the chapters in this book will serve as a guideline or framework to help organisations direct their efforts at increasing (and keeping) women in technical professions.

The situation in numbers

Annually, BCS compiles and publishes a diversity report. Initially instigated by the very active BCSWomen networking group, the report originally looked only at gender. Today, the report produces statistics and analysis for a broad range of under-represented groups and undertakes opinion surveys to reflect the mood of the industry and professions with regard to diversity.

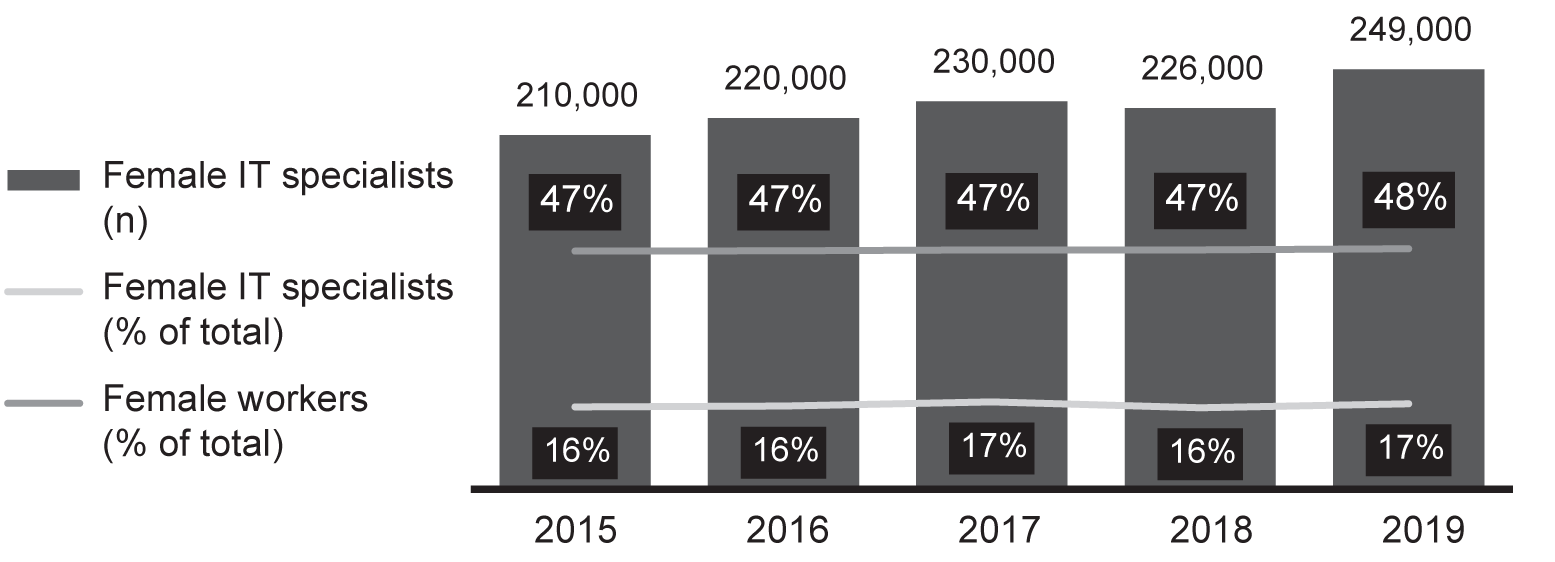

The 2020 report showed that while women made up around 50% of the working-age population, and 48% of them were working, only 17% of the IT specialists in the UK were female (BCS, 2020b). The numbers have fluctuated between 16% and 17% over the past decade (see Figure 1.2), and although it is true that the total number of IT specialists (male and female) has grown, the percentage of women is consistently low. While there is an acknowledged lack of skills in the technical professions, it is a shameful waste of the potential workforce that could be available for IT if we were to attract the remainder of these women workers.

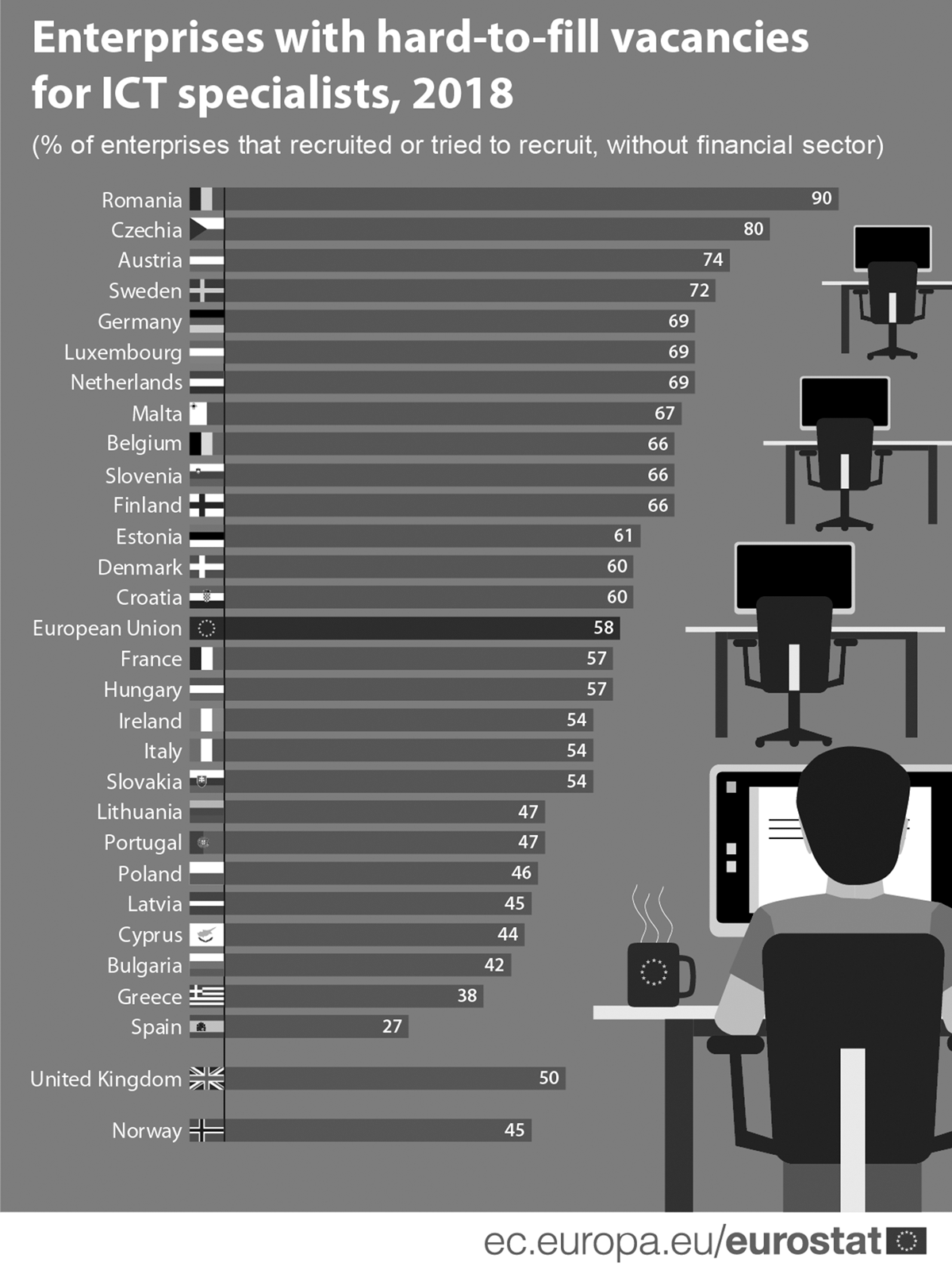

Across Europe, the figures are little better. The EU regularly publishes a digital scorecard for women and produces statistics for each of the aligned countries (European Commission, 2020). In 2019 this data showed that only in a couple of cases did the proportion of women creep over 20% female IT specialists in a country, while many nations reported figures in the region of 15% technical women, with the remainder far lower (see Figure 1.3). Overall, the EU believes that only one in six working IT specialists in the bloc are women.

Figure 1.2 Trends in workforce representation, 2015–2019. The number of women in IT is growing slightly annually, but the percentage of females within the industry remains the same year on year (Source: BCS, 2020a)

Figure 1.3 Women in Digital Index 2019. While the UK was fifth across the EU bloc with regard to women actively using technology, those with specialist skills are much more scarce across the whole group of countries (Source: © European Union, 1995–2021)

AT, Austria; BE, Belgium; BG, Bulgaria; CY, Cyprus; CZ, Czech Republic; DE, Germany; DK, Denmark; EE, Estonia; EL, Greece; ES, Spain; EU, European Union (overall); FI, Finland; FR, France; HR, Croatia; HU, Hungary; IE, Ireland; IT, Italy; LT, Lithuania; LU, Luxembourg; LV, Latvia; MT, Malta; NL, the Netherlands; PL, Poland; PT, Portugal; RO, Romania; SE, Sweden; SI, Slovenia; SK, Slovakia; UK, United Kingdom For details of the ranking system used by the EU, see European Commission (2020).

Research undertaken through the Open University, and addressed in Chapters 2 and 3 of this book, showed that in India, the proportion of young women entering the IT professions for a career is far greater (Sondhi et al., 2018). This suggests that in Europe we have a significant cultural problem to address, which will be covered in later chapters of this book.

In the IT professions, women tend to cluster in certain roles, just as they do in the broader workforce. For example, women make up larger numbers of those working in caring professions, HR, retail and marketing. The same types of divisions can be seen in the IT professions, as shown in Figure 1.4 (BCS, 2020a).

Figure 1.4 Female representation by IT occupation, 2019 (five-year average). Figures from the Office for National Statistics show that women cluster in IT operations, in project management and in web design, but are very under-represented as IT engineers, directors and possibly even coders (Source: BCS, 2020a)

Women make up larger numbers of IT operations technicians and project and programme managers, and fewer of the most senior IT directors. Women are well represented in web design but make up a smaller proportion of software developers. This may be down to socialisation, where women see themselves as more ‘creative’ than ‘technical’. IT engineering roles are where women are least found, but this is often a key skill that underpins one of the most senior technical positions, that of the IT architect.

Chapters 2, 3, 5, 6 and 7 of this book look at what needs to happen within academia and business to attract more women into the technical professions. We have used real examples of good practice and case studies from active organisations to show what is being done today to better attract women into technology courses and to show women how enjoyable careers in technology can be.

Some of the other statistics from the BCS diversity report demonstrate the cultural shift that needs to happen within our industry. The report shows that the unemployment rate for women in technology was 3.1%, more than double that of male IT specialists at 1.2%, suggesting that females may be less valued (BCS, 2020a). It is known that women were some of the first to suffer redundancies in the fallout from the 2008–2009 banking crash, and they were also those who felt the largest impact (Mukherjee, 2013). They have also been the ones to take on the majority of the caring responsibilities during the COVID-19 lockdowns, and consequently their jobs and prospects have suffered. More shockingly, and also representative of the value ascribed to women technical professionals, BCS (2020b) found that ‘female IT specialists were four times more likely to be working part-time than males (i.e. 16% versus 4%) – though most often as they did not want full-time work’ (p. 7). Also, an article in Harvard Business Review found that where they do take up flexible options, it can hold back their careers (Ely and Padavic, 2020).

Additionally, BCS (2020b, p. 7) found that:

- ‘At £18 per hour, the median hourly earnings for female IT specialists in 2019 was 14% less than that recorded for males working in IT positions (full-time employees).’

- ‘Female IT specialists are marginally more highly qualified than their male counterparts. In 2019, more than seven in ten (71%) held a degree or other higher-education-level qualification.’

- ‘Female IT specialists were more than three times less likely than males to hold an IT degree (4% compared with 13%).’

These statistics, and others produced from all parts of the UK public sector, UK industry, and similar institutions and organisations across Europe, go to show that we are not making the most of the potential in our workforce. We don’t derive the benefits that engaging more women, or more diverse groups, can bring. While the moral imperative to be more inclusive in our dealings with others in the work or academic sphere should drive the best behaviour, it is very often submerged below increasingly pressing business imperatives. For that reason, many organisations at the leading edge of work on diversity and inclusion have resorted to fully understanding and using a broad business case for diversity.

THE BUSINESS CASE FOR DIVERSITY

During the late 1990s there was little ‘evidence’ in the UK of the business case for diversity. Therefore, apart from the moral imperative, those of us working on the issues had little to add to our ‘business case’ to encourage our peer managers to work alongside us. However, we knew that we had to focus attention on attracting and retaining more women in technology roles. Fortunately, work was happening in the USA: Virginia Valian (1999) was writing papers and books on gender schemas and the Implicit Association Test team (see the glossary) was writing about implicit bias (Greenwald et al., 2003). However, this work had yet to really permeate the business community in Europe. The first exciting piece of credible evidence we saw was in a 2007 paper from McKinsey in its first paper of the Women Matter series (McKinsey, 2007). This outlined the financial benefits that could be achieved in companies with diverse management teams. Thankfully, McKinsey continues to produce a large body of work that outlines the financial benefits of diverse teams and annually produces a report that looks at this in many intersectional ways.

The 2007 report seemed to open the floodgates, bringing reports and statistics from leading business thinkers that spoke of the financial, brand, productivity, customer and innovation benefits of working with diverse teams.

As recently as November 2020, Accenture reported that the UK could increase its GDP annually by 1.5% if it were able to create more inclusive workplaces. Its belief is that this creates a more innovative mindset within the workforce and creates the opportunity for staff and companies to thrive (Accenture, 2020). Some argue that even one facet of inclusivity, the gender diversity pay gap, costs the UK economy up to £127 billion each year (DiversityUK, 2018). There is so much research that outlines the benefits of diversity to the British economy and the world economy, that organisations have started to work on diversity. However, as can be seen from the statistics above, we still have work to do to benefit from this where the IT professions are concerned. It isn’t that the evidence is missing, just that we need to set to work to increase the numbers of women working in technology and to ensure that they want to stay once they have arrived.

The remainder of this chapter lays out the most compelling reports and statistics highlighting the benefits of diverse teams in order to help with any business case that is needed and to ensure that managers and executives have great reasons for employing more women.

Around the year 2011, a woman colleague who had worked at F International, the all-female freelancer software organisation created in the 1960s, confided that the working environment had been ‘okay’ when it was all female, but, as the company merged with Xansa, and at the point when the numbers were around 50:50, she had enjoyed working there enormously. She felt that the gender mix made for a wonderful working environment. She followed up with the comment that, at the point when the numbers eventually skewed towards fewer than 30% female, that wonderful working environment and culture disappeared. If nothing else, this might make the IT workforce eager to create change.

The research reports mentioned in this book are just a small sample of the material that is now on offer to cover all aspects of the business case for diversity. We have tried to include work that is either relevant or current, but much more is and will be available.

The skills business case for diversity

Currently, across the European continent, there is a significant issue in every country around IT skills, as Figure 1.3 shows. Not only are countries enormously concerned about the digital literacy of the whole population but they are also concerned to ensure that companies have access to the skills required to fill the IT roles in industry and to ensure that technical skills are never a limiting factor to growth in their economies. Where countries believe that the digital economy will be the driver of GDP growth, it is essential to be able to access a constant pipeline of new entrants to the workforce with the appropriate expertise and experience. Eurostat regularly publishes statistics that reflect the reality for organisations that are unable to attract the technical skills that they need. In the UK, as shown in Figure 1.5, reportedly 50% of organisations find it difficult to recruit the skills that they need.

Nor is this a recent problem, as Figure 1.6 shows. The issues around recruiting the technical expertise required are getting worse, not better.

For that reason, we cannot, as a nation (or a continent), afford to waste the available talent out there. Chapters 2 and 3 of this book address the work that is being done within schools and academia to increase the numbers taking up specific IT and ICT topics for training. The pipeline of graduates of all diverse characteristics is essential. It is also imperative, given the gap in IT skills, that we look more broadly at the people available to us. An individual who understands the recruitment world and has a nascent passion for coding might well be our next recruit in robotic process automation, or an older individual who has spent their life working in legal or marketing could be our next data administrator or the next ‘creative’ to support our web design. ‘Switchers’ to our industry should not be overlooked, and many women who have spent time out for childcare or elder care may bring skills to our industry that broaden our perspectives on the next product or service we create. This topic is covered in later chapters.

Figure 1.5 Eurostat research on the percentage of companies reporting technology roles that are hard to fill, by country (Source: © European Union, 1995–2021)

Figure 1.6 The increase since 2011 in companies finding hard-to-fill vacancies in IT (Source: © European Union, 1995–2021)

At the moment, women make up 50% of the working-age population in the UK (around 15.5 million women). Their employment rate is around 72%, which gives us some scope to grow our technical population, and, as COVID-19 decimates our high streets and industries, we should look to retrain a large cohort of switchers to support our requirements. Of course, we will need to govern our management team biases around the belief that if a person has been a secretary or a shop worker, they could never work in tech, and we will need to ensure that we provide for the approximately one third of the female working-age population who need to be able to work flexibly to support their caring commitments. Of course, the male workforce may have caring responsibilities too, and might equally enjoy the right to flexible working. What is clear is that the 2020 pandemic has changed everything about the way we look at home working, and the cat is really now out of the bag about what it is possible to achieve (and manage) when working at home.

The breadth of skill lies in diverse communities

The precedence of the Russell Group universities1 meant that during the 1990s in the UK, major employers only looked for their graduate intake from these prestigious universities. IT employers sought graduates from universities such as Warwick and Southampton, which were known for their expertise in technology. Unconscious bias (see Chapter 4) was not widely understood and so it is reasonable to assume that many organisations would have deemed the White male graduate to be the cream of the talent out there, and consequently the focus of recruiters would have rested with this community. Also, during this era and into the start of this century, media stereotypes of workers in the technical professions were not really conducive to attracting women. The image of an unkempt, possibly unwashed worker, glued to a terminal with a pile of uneaten pizzas at their side, would not have shown many young women that there was a place for them within the IT community.

Now, however, given the arguments above and the push to foster inclusivity within the workplace, employers are looking for more women and more people from ethnic minority backgrounds to join their teams. They are beginning to realise that in a world where technology jobs are increasingly hard to fill, the large numbers of females who graduate from UK universities are worth attracting. According to the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA), over 57% of all higher education students were female in 2017/18 and 63% of undergraduates of all disciplines were female (HESA, 2019). Since the UK IT professions are crying out for additional talent, it makes sense to fully utilise all the available and diverse groups in the working-age population. Again, it is important that managers understand that the skills required for IT roles are not just those that can be acquired by undertaking a Computer Science or IT degree. Just as with any profession, technology requires a broad raft of skills.

In the UK today, government statistics based on Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS) returns suggest that, in many cases, individuals from ethnic minority communities undertake higher education at greater rates than the White British population (Gov.uk, 2020). The astute employer who ensures they recruit a mix of gender and ethnicities is more likely to get the best spread of skills on offer. Equally, those employers who recognise that age comes with wisdom and broad life experience will not throw out the workers who have passed the age of 50 in favour of a younger and cheaper workforce. Instead, they will recognise that a true mixed team that reflects the population will ensure that their software products or services will embrace a wider range of possibilities and help them to beat the competition, through the wisdom of the older workforce and the innovation brought about by diverse teams.

Research on gender schemas by Virginia Valian (1999) suggested that once the diverse element of the workforce hits 30% saturation, there is a self-sustaining loop. It is therefore particularly important that organisations maintain their work on the drive to greater diversity of employees until such a number is attained, and then, through work on retention, sustain the diverse make-up of the workforce.

The value to the brand of diverse teams

Early on in the race for diversity, organisations understood that if they were to attract the broadest range of talent, and win with a wide group of clients, not only did they need to have excellent diversity policies but their public face also needed to reflect the diversity of the population. It became clear that this conferred an advantage. As early as 2007, McKinsey was reporting in the Women Matter paper mentioned earlier that nearly 70% of companies that implemented gender diversity policies were reporting improvements in their brand image (McKinsey, 2007).

The other perspective on the value of diversity to the brand and image is the potential to reduce costs around recruiting and attraction of staff. With significant proportions of the employment market looking for good cultural fit with their next employer, the understanding that what a company projects in its external image will be reflected in its diversity policies and culture can have a natural ‘pull’ effect for new starters.

Reduced attrition

Managers and HR departments typically want to drive down attrition. They understand the significant costs associated with hiring professionals into their teams, in terms of both manager time and recruitment spend. They also know that when a staff member leaves the organisation, the investment in time and training of the individual is a sunk cost to the business, and significant skills are lost. For that reason, with a stable economy and business, losing people incurs costs that organisations would prefer to avoid.

Experience suggests that staff members commonly leave due to feeling unwanted or unvalued (as shown by surveys of leavers and cultural surveys of businesses). This can happen by means of caustic cultures and unmanaged biases. When working cultures are inclusive to all, and when the whole team feels valued for the difference they bring, then benefits accrue. One of the lesser noticed benefits is the reduction in attrition. The more inclusive an organisation feels, the more valued the worker, the more recognised the potential and the less likely the worker is to walk away. The improvement in working cultures is tangible. Of course, this can only happen when all members of the team, no matter what their intersectionality, are heard and feel appreciated.

The financial business case for diversity

The 2007 McKinsey Women Matter paper made the – at the time – compelling suggestion that ‘companies where women are most strongly represented at board or top management level were also the companies that performed the best’ financially and organisationally (p. 3). The paper outlined the state of affairs for women in business across the USA and Europe, and at its core examined whether greater diversity would show better economic performance. It looked at measures around organisational excellence and financial performance, and it identified a correlation between those companies that ranked higher in organisational excellence and those that had better economic performance. The paper also carefully drew a correlation showing that those organisations where there were more women among the top management functions and where there were the most gender diverse management teams were performing better on earnings before interest and tax (EBIT), return on equity (ROE) and share price. The differences were significant enough to capture the attention of businesses across the western world. The paper clearly showed that those organisations that had the most diverse management teams were making more EBIT and ROE, and had better share prices.

McKinsey continued its output on diversity both annually and quarterly, and is responsible for a great deal of research and material. Relatively recent papers from McKinsey show only too clearly the benefits of teams with mixtures of protected characteristics. In spring 2012 a report in McKinsey Quarterly analysed the benefits of gender and ethnic diversity, showing that those organisations across the USA and Europe that embraced greater diversity were likely to see over 50% better ROE and, on average, 14% better EBIT than those which didn’t (Barta et al., 2012).

The evidence McKinsey produces is compelling, and it stands out as an organisation that today ensures a steady stream of analysis around the business case for diversity.

The arguments outlined in numerous papers on the financial benefits of diversity in teams deserve to be picked apart. McKinsey did so in its seminal 2007 paper using its ‘Organisational Performance Profile’ to depict the various aspects of work within a typical organisation that would benefit from diversity and that would, in turn, lead to gains in revenues or profits. We do so here by looking at the diversity benefits for productivity, competitiveness, innovation, legal compliance or risk, culture and various other elements that support growth in revenues linked to acquiring and facilitating diverse teams.

Since 2015 McKinsey has produced a series of three reports on the business case for diversity and it remains the place to go for insightful research (Hunt et al., 2015; Hunt et al., 2018; Dixon-Foyle et al., 2020). The third report, in 2020, suggests that the ‘business case remains robust but also that the relationship between diversity on executive teams and the likelihood of financial outperformance has strengthened over time’ (Dixon-Foyle et al., 2020, p. 3).

The increased productivity business case for diversity

Increased productivity is seen as a key benefit of employing diverse teams and one of the feeds into the financial business case for diversity. There are various ways in which productivity could be enhanced by greater diversity. Several research papers (as discussed below), and much of the current thinking on inclusion, suggest that there is greater productivity when staff perceive the working environment to be more inclusive and more pro-diversity. In the early years of research, causality was hard to prove, but more recently there have been papers confidently stating that diverse teams are more productive, produce better numbers on customer satisfaction surveys and key performance indicators (KPIs), and win more business from diverse customer sets.

Inclusivity produces more productive staff

In Australia, a survey of 3,000 working people revealed that inclusion in the workplace mattered to those surveyed (O’Leary and Legg, 2017). They felt it offered them better team performance, minimised the risk of harassment and discrimination (for all), and provided for greater employee satisfaction and success. All of these components of working life support greater productivity in teams. For 75% of the staff surveyed, action on inclusivity was approved; however, more importantly, the survey found that those working in inclusive teams were:

- 10 times more likely to be ‘highly effective’ than others;

- nine times more likely to be innovating;

- five times more likely to be providing excellent customer service.

These are the facets of inclusive teams that support the theories around additional financial and innovation benefits. The Australian survey also showed that staff were significantly happier with their jobs and employers, and had their careers managed in more productive ways when they worked in more diverse teams.

A 2019 paper from the University of Oxford showed a causal link between the weekly happiness of a call centre team and their sales performance (Bellet et al., 2019). The link between staff happiness and productivity has been mooted for many years, but in this paper the relationship is shown to have significant causality.

Another paper, by Beverley Alimo-Metcalfe (2002), makes it clear that the benefits of having women on the leadership team might also be an aid to productivity. Alimo-Metcalfe’s position is that this is due to the female propensity to choose transformational leadership styles over transactional styles. Transformational styles are said to involve leading a team through a shared vision, in contrast to transactional styles, which are much more about punishment or reward. Much research was done early in the 21st century about the benefits of transformational leadership and increased staff productivity, and Alimo-Metcalfe draws correlations in her research between diverse leadership and happier and more productive teams.

Facing customers with ‘people like them’ makes for more productive salespeople

One of the amusing things about the young tech sales workforce is that they are unaware of the impact that they may have on their client set. The hungry young salesperson looking for a sale with their male customer, discussing the weekend’s football, may be much more uncomfortable when challenged to visit a female chief information officer. Equally, the young saleswoman who fails to understand the importance of sport to her male clientele is disadvantaged from the start because she may not be able to bond as easily with her client. This is not to say, of course, that there aren’t female football fans or that all men like the sport; however, as statistics from 2021 show, it is more likely to be a male hobby than a female one (Statista, 2021).2

Both sets of salespeople will have been told that ‘people buy from people they like’, but they may struggle to culturally ‘fit’ with their client. Salespeople are asked to subtly mimic body movements of clients, to talk about the things their clients want to talk about and imagine themselves in the mindset of the buyer. When there is a mismatch, this is much more difficult, and yet organisations that fail to offer a diverse salesforce cannot always match clients to salespeople. When companies can pair their clients with a range of salespeople, it is much more likely that they will get a ‘match’ and a mutual understanding, and this can enhance the sales opportunities for an organisation. This can only happen if the diversity of the team matches the diversity of the client set. If an organisation’s customers are attuned to diversity, its internal make-up and culture may be changing, so business-to-business organisations should be very aware of this. Similarly, for business-to-customer companies, it is important that the product developers and owners reflect the true diversity of their actual and potential marketplaces, otherwise output from innovators or focus groups could be discounted due to institutional biases.

Enhanced customer satisfaction

A carefully researched paper by PwC (2015) suggested that increased workforce diversity leads to an improved customer satisfaction response. An equally rigorous paper outlining research undertaken in JCPenney in the USA shows clearly that ‘store units perceived to foster extremely pro-diversity work climates elicited greater customer satisfaction than those with less favourable diversity climates, especially for units with highly pro-service climates and greater ethnic minority representation’ (McKay et al., 2011, p. 799). This is an important effect for many businesses and employees who have client satisfaction as a key indicator of performance. An organisation can make a direct and beneficial impact on this key aspect of customer retention by increasing the diversity of the workforce.

The innovation business case for diversity

It took the advent of women astronauts working on the International Space Station to make it obvious that the toilet facilities had only been created for male users. This demonstrates the real benefit to be found from having development teams with different life experiences designing and creating the products and software that we use. The result is the more frequent creation of new and unique selling propositions or more fully rounded services and products.

Diverse groups create greater innovation

Harvard Business Review is often a great source of opinion on the business case for diversity. In one paper, it concluded that companies with stronger diversity are ‘70% likelier to report that the firm captured a new market’, and again showed a connection between greater gender diversity in the executive leadership and better financial performance of an organisation (Hewlett et al., 2013a). While there was very limited research at the start of the century, the message on the increased innovation in diverse teams is clearly hammered home by many industry watchers at the end of its second decade.

Forbes also has much to say on diversity and inclusion. A very readable Insights paper found that diversity is ‘a key driver of innovation and… a critical component of being successful on a global scale’ (Forbes, 2011). In research looking at 300 companies, Forbes showed that those surveyed believed that diversity helped them to innovate and that they received a boost in productivity from diverse teams. It is clear that the companies in the survey were using locally based groups of employees to give insight into the cultures, perceptions and needs of the populations being served. It seems obvious that any organisation that fails to take into account the needs of clients will have limited success in comparison to firms that do care about customer needs. It is then really important to use the different perspectives of a wide group of employees to build products and services that match client expectations, and to use innovation to create unique selling propositions and thereby innovate to beat the competition.

Where a team brings diverse perspectives to the creation of a service or a product for a marketplace or client, respecting and reflecting the buyer’s culture (and beyond) means that the purchaser is more likely to value the offering that has been created with their needs in mind. This is shown perfectly by the example of the gaming industry.

Gaming: Supporting the whole potential of the market through diversity It is thought that the number of women who play computer games is roughly equal to the number of men playing in the UK today (Clement, 2021). However, according to the Thomson Reuters Foundation, only 22% of gaming industry workers are females (Taylor, 2019). Moreover, the International Game Developers Association (IGDA) suggested in a 2020 report that while diversity is becoming a recognised concern for the industry, it is the minority groups working within the industry who ‘bear these concerns the most and who report challenges related to them’. There are thought to be several significant issues that this is causing:

- A male culture, driven by younger male coders and potentially caustic enough to discourage women from remaining in the gaming industry: the IGDA report suggests that the industry is perceived to be both sexist and racist by a large percentage of its survey respondents, but that those who identify as male have far less of a problem with this than those who identify as female.

- An industry that lacks diversity of women and people of colour, and fails to innovate and successfully attract significant numbers of female buyers to its products: where the industry lacks an understanding of females’ product requirements or diverse perspectives around games and gaming, it is far less likely to create an offering that captures the imagination of the female purchaser.

- A customer set that has regularly been accused of misogyny but with little resource to fix it except the employee groups who are trying to fix it from within (Lorenz and Browning, 2020; Rosenblatt, 2020): as we shall see in later chapters, without an executive backer and a vision to create an inclusive workplace, any change for the better is hard to achieve.

- An industry reputation that will create difficulty in accessing a willing female (or other minority) workforce.

Figure 1.7, from the IGDA’s 2020 report, suggests that there is some way to go to shift the negative perceptions that are attributed to the industry in the minds of women. Yet, if the industry is to ensure the continuing support (and purchasing power) of the female gamer, it is evident that change will be required.

Figure 1.7 Factors relating to negative perceptions of the games industry by gender. The percentages refer to the people in each group (non-binary, transgender, women, men) who perceived each factor to be problematic (With thanks to the IGDA)

This continuing under-representation of women in the gaming industry means that it is difficult to break the cycle. The NextGen Skills Academy surveyed nearly half of the women working in the gaming industry in the UK and found that nearly half felt that their careers were held back because of their gender (Pearson, 2014). This, if not worked on, will have a significant impact on retention of workers.

The compliance, legal and governance business case for diversity

There are several legal, compliance-based and governance reasons why an organisation might want to ensure diversity at all levels.

Access to work or bidding rights

Increasingly, companies and organisations (and in particular public sector organisations) make diversity a requirement of bidding for work. They insist that the bidder lay out in full the diversity policies and efforts that are being made across the full set of protected characteristics. Where companies cannot do this, they may be unable to submit tenders for opportunities. And, where it is clear they have minimal interest in diversity issues, they may be disadvantaged in the tender process.

Diversifying the supply chain

As the business imperative for diversity becomes embedded, organisations are increasingly looking beyond their own workforce to drive inclusion and diversity through their supply chains. For those that outsource their IT functions, it may be important to understand what role diversity plays for their suppliers. For suppliers, adherence to the diversity standards within the supply grouping will be important. Consequently, there are benefits all along the chain to supporting, attracting and retaining diverse teams.

Governance, risk management and strategic decision-making

The first country to initiate the legal enforcement of the requirement for a specific diversity for company boards was Norway in 2002. This became mandatory by 2008. When it happened, there was an outcry from companies within the country, claiming that they would never be able to find suitably qualified people to meet the target. There was also a belief that they would need to take on poorer candidates for board roles, as though women had inherently poorer skills than their male peers. And there was a pervasive fear that the country and its industries would become uncompetitive because of the requirement. Work done in Norway and across the world since then suggests that the following benefits are seen as a result of having diverse boards:

- With regard to governance and corporate risk management, outcomes showed that risk assessment and monitoring were more rigorous (Dhir, 2014).

- Boards with more diversity were more focused in their strategic decision-making (Nielsen and Huse, 2010).

- Where there are more than a token number of women on boards, innovation within the company is increased (Torchia et al., 2011).

- Companies where the board is more diverse set a better example to diverse groups within the employee base, since it is agreed that if people can see role models like themselves in the higher levels of the company hierarchy, they will believe they too can achieve those levels.

In any company, it is clear that where there is only a token woman, or where it is difficult for women on the board or executive teams to have their voices heard, any positive outcomes from diversity can be missed. Within the Norwegian experience, there were a couple of factors that detracted from the potential gains to be made from the push to see larger numbers of women at board level. The women selected for the boards were repeatedly recruited from the same set of women and the companies did not source candidates more widely, so a group of derisively named ‘golden skirts’ acquired multiple roles on boards. A dip was also seen in revenues in some of the companies; however, their status prior to the ruling has been cast in doubt. Generally, it was felt that the benefits in broader human capital would soon ensure that this was only a blip (Smith, 2018).

The avoidance of related legal issues as diversity is embraced within the business

Companies want to ensure that they do not face litigation with regard to diversity. The four modes of discrimination outlined in the 2010 Equality Act in the UK (direct discrimination, indirect discrimination, harassment and victimisation) are echoed across Europe and the USA in various forms. Companies need to ensure that staff, members and customers are not discriminated against either directly or indirectly, and that they are not harassed or victimised. It is becoming much harder to pinpoint ‘protected characteristics’, which may be well hidden, and therefore equality, diversity and inclusion initiatives have driven an understanding across organisations of the value of inclusivity and the need to embrace the value that each individual can bring.

Employees, members and customers who bring cases against organisations can eat up valuable staff time seeking resolutions and, where discrimination cases or employment tribunals are won by the employee, there is a significant loss of face for the organisation and brand damage could ensue. Oracle certainly had a lot of bad press as a result of a tribunal win by Karen Carlucci in 2004, and with the long-term memory of the web we are still talking about it today (see e.g. Rosenblatt and Burnson, 2020).

THE DANGERS OF DIVERSITY WITHOUT INCLUSION

Where organisations bring in diverse groups of people but fail to understand the importance of creating an inclusive environment in which everyone is valued for being just who they are, organisational efforts are wasted. Bringing in diverse teams to enhance innovation only works if teams and managers are listening to the opinions of everyone and giving them equal weight.

There is research supporting the additional requirement for management to listen to and include the whole team. This can easily be handled by good corporate policy, management training in inclusive leadership, and a culture with a willingness to engage with everyone on the team for the greater good. A report from the Center for Talent Innovation makes clear that ‘inclusive leader behaviors effectively “unlock” the innovative potential of an inherently diverse workforce, enabling companies to increase their share of existing markets and lever open brand new ones’ (Hewlett et al., 2013b, p. 2).

The push for diversity and inclusion within organisations does put the emphasis on managers and management teams. A paper from Ray Reagans and Ezra Zuckerman in 2001 suggested that diversity in teams leads to a reduced capacity for coordination and that relationships (and therefore communications between teams) might not be as strong as those in a team of like-minded and similar individuals. However, the abovementioned report from the Center for Talent Innovation makes it clear that without inclusive leadership, the value of mixed teams can easily be lost (Hewlett et al., 2013b).

Harvard Business Review reported that the benefits of diversity weren’t assured without some effort (Finkelstein, 2017). Managers and companies need to facilitate good communications between their teams, and leaders need to be fully committed to diversity and supporting their staff. Inclusive leadership styles and behaviours will ensure that organisations can realise and maximise the potential benefits achieved through mixed teams.

Failure to use the diversity that has been acquired

Where companies have achieved diversity in their teams (whether that be in sales, technical, teaching, development or support teams) but they fail to value their people, then the opportunity to match sellers to buyers, or to match developers to app consumers, or to innovate for new product development, is lost. They will not benefit from all of the potential outlined in this chapter because they will not be actively listening when an outstanding new idea surfaces. Some companies use the Pareto principle (or the 80:20 rule) to split client organisations into the most important (by revenue earning potential) and the least important. However, if such companies then fail to match a female salesperson to a key customer because of the biases of her manager, they cannot benefit from efforts around diversity. The team that fails to hear a tech woman’s ideas at the product development stage may fail to create a unique selling proposition. As we show in Chapter 4, organisations need to work on the unmanaged biases of their leadership teams in order to capitalise on the diversity of thinking within their teams.

Tips and tricks for companies and institutions

- It is important to ensure that your management, executive and board teams understand the business case for diversity. Relying on their goodwill or moral compass will not be sufficient to ensure that they seek to constantly meet company and team objectives on diversity. Some organisations have gone so far as to add bonuses for managers who meet and exceed targets and expected behaviours around diversity. It may, however, be sufficient to ensure that each manager has personal annual objectives on aspects of diversity and inclusive behaviour – for example, ratios of how many hires should be from diverse talent pools, or measurable equality and fairness objectives in talent management behaviour.

- Training for managers on transformational leadership styles or inclusive leadership behaviours will ensure that managers are able to capitalise on the benefits that diverse teams can bring.

- All managers who hire or assess others in the organisation need to be educated on equality, diversity and inclusion. For this group, training is essential in managing unconscious bias, since their unmanaged implicit biases may lead them to favour some social groups over others. As a result, organisations may miss out on women, switchers, neurodiverse groups and many others if they don’t understand how their biases play out in recruitment and assessment of staff.

- Executives and boards must fully endorse diversity initiatives within the organisation. They should be seen as instigators of efforts on diversity, inclusion and countering bias.

- Boards should receive training on the benefits of diversity and bias management before the rest of the organisation, to ensure that their behaviours are reflective of the inclusivity they want to engender.

- Organisations that debate bias and inclusivity internally are thought to benefit the most from inclusion training programmes. This, and the training on bias, is not the only programme that should be undertaken by companies, but it should form part of a wider effort looking at culture, inclusivity and behaviours within the organisation.

- Monitoring (see ‘What can organisations do?’ in Chapter 4) is key to an organisation understanding its starting point and building its diversity projects.

- None of the benefits of inclusion that pertain to innovation can be taken up if managers and team leaders are not listening to what diverse members of their teams are contributing. It is therefore essential that managers are trained in inclusive leadership, emotional intelligence and countering unconscious bias.

SUMMARY

We have been pushing the business case for diversity in the UK for many years. I had personal involvement in this during my work in a large IT corporate and working with Intellect (now TechUK) in the early years of the new millennium, and we are still talking about it today. There is an enormous amount of research on the business case for diversity and inclusion, and there now seems to be clear acceptance of the competitive edge these offer to organisations that fully embrace them. The arguments in this chapter may be useful to diversity teams, employee resource groups or grassroots organisations aiming to win arguments around acquiring funding, but they should also be a great reminder of the real benefit of valuing and respecting everyone in the organisation, regardless of their role or seniority.

In the following chapters we look at what is being done in schools and higher education in the UK to increase the numbers of girls and women in the pipeline to becoming IT professionals, and touch on what more needs to happen. Later, we look at the impacts of bias and socialisation on the decisions that we and our teams might be taking. Finally, we outline how to build or enhance a project to bring greater diversity to technical teams, and give specific ideas on attracting and retaining women in the technical workforce. We are convinced that lots of support is required to ensure that the technology teams of the coming decades are wonderfully diverse.

REFERENCES

Accenture. (2020). Who we are is how we’ll grow. Available from https://www.accenture.com/_acnmedia/PDF-139/Accenture-Who-

We-Are-Is-How-Well-Grow.pdf.

Alimo-Metcalfe, B. (2002). Leadership & gender: A masculine past; a feminine future? Leeds: University of Leeds.

Barta, T., Kleiner, M., & Neumann, T. (2012). Is there a payoff from top-team diversity? McKinsey Quarterly. Available from https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-

insights/is-there-a-payoff-from-top-team-diversity.

BCS. (2020a). BCS diversity report 2020: Part 1. Available from https://www.bcs.org/media/5767/diversity-report-

2020-part1.pdf.

BCS. (2020b). BCS diversity report 2020: Part 2. Available from https://www.bcs.org/media/5766/diversity-report-

2020-part2.pdf.

Bellet, C., De Neve, J.-E., & Ward, G. (2019). Does employee happiness have an impact on productivity? Saïd Business School Working Paper 2019-13.

Clement, J. (2021). Share of paying gamers in the United Kingdom as of May 2018, by gender and platform. Statista. Available from https://www.statista.com/statistics/914117/paying-

gamers-

gender-platform-united-kingdom.

Dhir, A. A. (2014). Norway’s socio-legal journey: A qualitative study of boardroom diversity quotas. In Challenging boardroom homogeneity: Corporate law, governance, and diversity (pp. 101–146). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

DiversityUK. (2018). The value of diversity report. Available from https://diversityuk.org/involve-launches-value-

of-diversity-report.

Dixon-Foyle, S., Dolan, K., Hunt, V., & Prince, S. (2020). Diversity wins: How inclusion matters. McKinsey & Company. Available from https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/

diversity-and-inclusion/diversity-wins-how-inclusion-matters.

Ely, R. J., & Padavic, I. (2020). What’s really holding women back? Harvard Business Review. Available from https://hbr.org/2020/03/whats-really-holding-women-back.

European Commission. (2020). EU women in digital scoreboard. Available from https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/women-

digital-scoreboard-2020.

Finkelstein, S. (2017). 4 ways managers can be more inclusive. Harvard Business Review. Available from https://hbr.org/2017/07/4-ways-managers-can-be-

more-inclusive.

Forbes. (2011). Global diversity and inclusion: Fostering innovation through a diverse workforce. Available from https://www.forbes.com/forbesinsights/innovation_diversity.

Greenwald, A. G., Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2003). Understanding and using the implicit association test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 197–216.

Gov.uk. (2020). Percentage of state school pupils aged 18 getting a higher education place by ethnicity over time. Available from https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/education-

skills-and-training/higher-education/entry-rates-

into-higher-education/latest.

HESA. (2019). Higher education student statistics: UK, 2017/18 – Student numbers and characteristics. Available from https://www.hesa.ac.uk/news/17-01-2019/sb252-higher-

education-student-statistics/numbers.

Hewlett, S. A., Marshall, M., & Sherbin, L. (2013a). How diversity can drive innovation. Harvard Business Review. Available from https://hbr.org/2013/12/how-diversity-can-

drive-innovation.

Hewlett, S. A., Marshall, M., & Sherbin, L. with Gonsalves, T. (2013b). Innovation, diversity and market growth. Center for Talent Innovation. Available from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b9553ee271

4e5533f0a3eaa/t/5baa6f09f4e1fcc9d3253d11/

1537896203533/Innovation+Diversity+Market+

Growth+-+CTI+-+2013.pdf.

Hicks, M. (2018). Programmed inequality. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hunt, V., Layton, D., & Prince, S. (2015). Why diversity matters. McKinsey & Company. Available from https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/

our-insights/why-diversity-matters.

Hunt, V., Yee, L., Prince, S., & Dixon-Fyle, S. (2018). Delivering through diversity. McKinsey & Company. Available from https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/

organization/our-insights/delivering-through-diversity.

International Game Developers Association. (2020). Developer satisfaction survey 2019: Industry trends and future outlook report. Available from https://s3-us-east-2.amazonaws.com/igda-website/wp-content/

uploads/2020/11/25095744/IGDA-DSS-2019-Industry-

Trends-Report_111820.pdf.

Lorenz, T., & Browning, K. (2020). Dozens of women in gaming speak out about sexism and harassment. New York Times. Available from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/23/style/women-

gaming-streaming-harassment-sexism-twitch.html.

McKay, P. F., Avery, D. R., Liao, H., & Morris, M. A. (2011). Does diversity climate lead to customer satisfaction? It depends on the service climate and business unit demography. Organization Science, 22(3), 788–803.

McKinsey. (2007). Gender diversity: A corporate performance driver. Available from https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/

our-insights/gender-diversity-a-corporate-

performance-driver.

Mukherjee, A. (2013). Recovery with rights: Towards an economy that cares. Social Watch. Available from https://www.socialwatch.org/node/16103.

Nielsen, S., & Huse, M. (2010). The contribution of women on boards of directors: Going beyond the surface. Corporate Governance, 18(2), 136–148.

O’Leary, J., & Legg, A. (2017). DCA-Suncorp Inclusion@Work Index 2017–2018: Mapping the state of inclusion in the Australian workforce. Diversity Council Australia. Available from https://www.dca.org.au/research/project/

inclusion-index.

Pearson, D. (2014). Survey: 45% of the UK industry’s women feel gender is a ‘barrier’. Gamesindustry.biz. Available from https://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2015-01-13-

survey-45-percent-of-the-uk-industrys-women-feel-

gender-is-a-barrier.

PwC. (2015). The PwC diversity journey: Creating impact, achieving results. Available from https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/about/diversity/global-

diversity-week.html.

Reagans, R., & Zuckerman, E. W. (2001). Networks, diversity, and productivity: The social capital of corporate R&D teams. Organization Science, 12(4), 502–517. doi: 10.1287/orsc.12.4.502.10637.

Rosenblatt, J., & Burnson, R. (2020). Oracle women score major win in court battle over equal pay. Bloomberg. Available from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-05-01/

oracle-women-score-major-win-in-court-battle-over-equal-pay.

Rosenblatt, K. (2020). Video game streaming platforms investigating allegations of sexual harassment. NBC News. Available from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/video-game-

streaming-platforms-investigating-allegations-sexual-

harassment-n1231689.

Smith, N. (2018). Gender quotas on boards of directors: Little evidence that gender quotas for women on boards of directors improve firm performance. IZA and Aarhus University. Available from https://wol.iza.org/uploads/articles/7/pdfs/gender-quotas-

on-boards-of-directors.pdf.

Sondhi, G., Raghuram, P., Herman, C., & Ruiz Ben, E. (2018). Skilled migration and IT sector: A gendered analysis. In S. I. Rajan (Ed.), India migration report 2018 (pp. 229–248). New Delhi: Routledge.

Statista. (2021). Share of adults that watch men’s English Premier League football matches in Great Britain in 2020, by frequency and gender. Available from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1093874/share-of-british-

adults-that-watch-men-s-premier-league-football-by-

frequency-and-gender.

Taylor, L. (2019). Girls got game: Young women hope to level up video game coding skills. Thomson Reuters Foundation News. https://news.trust.org/item/20190418094630-4mpd0.

Thompson, C. (2019). The secret history of women in coding. New York Times. Available from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/13/magazine/women-coding-

computer-programming.html.

Torchia, M. T., Calabrò, A., & Huse, M. (2011). Women directors on corporate boards: From tokenism to critical mass. Journal of Business Ethics, 102, 299–317.

Valian, V. (1999). Why so slow? The advancement of women. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

NOTES

1 There are 24 Russell Group universities. These are research intensive and generally have higher entry requirements.

2 Statistics show that while 35% of men frequently watch Premier League football, less than half that number of women do so, and across European countries ‘most football fans were male’ with the UK and France being the countries where the largest proportion of football fans are male.