8

Designing a Web Site

“Some men give up their designs when they have almost reached the goal; While others, on the contrary, obtain a victory by exerting, at the last moment, more vigorous efforts than ever before.”

—Herodotus

Topics Covered in This Chapter

Web Versus GUI: Similarities and Differences

Implementing applications on the Web has become a popular alternative to developing operating system applications, particularly if you want to develop applications for different operating system platforms.

However, a Web GUI interface has similarities and differences from a desktop GUI application that you must be aware of. Both interfaces adhere to some of the same rules, yet the Web must adhere to its own standards that are dictated by the Hypertext Markup Language (HTML), as well as related Web languages regarding the placement of text and objects on a Web page.

Technologies are beginning to blur the line between the desktop GUI and the Web, and more companies are developing Internet-enabled applications that allow users to use desktop software that interacts with the Web.

If you’re going to develop for the Web, there are plenty of Web myths out there that have been dispelled. You need to know about these myths so that you’re aware of what affordances and constraints you have with Web design. Like GUI interfaces, Web interfaces have different postures for different types of Web sites.

Web engineering is an integral part of Web design. Without the programming and database development behind the interface, you won’t be able to create an effective Web site if you want to include e-commerce, Web form(s), or user databases with your Web site.

You should also understand Web standards and the four rules of Web design. The rules don’t apply all the time, so this chapter tells you when it’s okay to break the rules.

Web Versus GUI: Similarities and Differences

When you design for the Web, you need to be aware of the differences between desktop GUI interfaces and Web interfaces. They contain different types of constraints.

GUI Rules

A GUI contains a specific set of rules for how the user interacts with the computer. Following are these rules:

- A desktop metaphor uses icons to represent files and programs.

- The mouse (or an alternative device such as a trackball) and keyboard can be used to manipulate objects.

- Windows allow you to view and manipulate data within each window.

- The arrangement and storage of windows allow you to work on more than one program at once.

- Rigidly enforced standards ensure that windows look and feel reasonably the same. This cuts down on the learning curve needed to learn a new program because the interface is similar.

Web Rules

Web sites also have rules, some of which overlap with GUI rules:

- The Web uses a specific program called a browser that runs in the GUI to access the Web site. Therefore, when the user accesses the site, the user is required to open a window and use the mouse to manipulate objects there.

- The Web is constrained by requirements in HTML and other Web languages regarding placement of objects on a Web page. Although new Web technologies (such as Adobe’s Flash animation software) are blurring the line between the desktop and the browser, most people still use browsers; therefore, browsers still constrain Web design.

- The look of a Web page is constrained by a set number of colors and fonts that all Web browsers can display, called Web-safe colors and fonts. Using Web-safe colors and fonts, the look of the Web page will look reasonably the same way on all computers running all available browsers. The Amazon Web site uses Web-safe colors and fonts, as shown in Figure 8.1.

Figure 8.1. The Amazon Web site has Web-safe colors and fonts.

© Amazon.com, Inc. or its affiliates. All Rights Reserved.

The look of a Web page is not constrained by rigid standards, although there are generally accepted usability conventions that you should adhere to for the look and feel of a Web page. I’ll discuss these standards in more detail later in this chapter.

Internet-Based Applications

The GUI desktop and the browser have been blurring as more and more users equate the desktop computing experience with the Web experience. People are using technologies such as the Java programming language, the ActiveX and PHP scripting languages, Adobe’s Flash animation software, AJAX and Dynamic HTML, and even more proprietary solutions such as Microsoft .NET languages and related software to create richer, more interactive Web applications.

These technologies make it easier than ever to create a Web-centric application that’s available from the desktop and transparent to the user. That is, the user will not be able to tell when the application is accessing the Web to exchange information with online resources such as one or more databases. The user will be able to use the desktop GUI to manage online resources without having to use a browser, and your Internet-centric application will have a richer interface and richer feedback than a Web interface.

Therefore, you will find that both GUI and Web affordances and constraints will apply in those situations. Be aware that many affordances and constraints in designing an Internet-based application will depend on the technologies you use to build your application. As always, consult your personas and find out whether an Internet-based application is the path that your users want you and your project team to take.

Web Myths

There are plenty of myths about Web site design, and if you adhere to any of them, you’ll make your users’ experiences worse rather than better. And that will translate into people leaving your site and not coming back.

This group of myths comes from several different sources, including Cooper and Reimann (2003), Web sites that discuss Web myths, and your author. These myths fall into several different categories:

Before you design for the Web, be aware of these myths so that you can dispel them in the planning stages.

Usage

Web usage myths have only grown over the years, and a lot of frustration about using the Web has come from misconceptions about how to use the Web. Before you design for the Web, understand the myths about how people use it. (The myths are bold, and the truth appears after the myth.)

- A Web interface is easy to use—If all you have is a static Web page with some text and a few links, this may be true. However, in recent years, the Web has become much more interactive, including forms, frames, scripts, and other embedded applications that have made Web interface design as complicated as interface design for a desktop application. Web interfaces don’t yet provide all the rich feedback and flow of a desktop application, so there are also design constraints of which designers must be aware.

- The Web and Internet are one and the same—The Web is only the graphical interface that allows people to share information over the Internet. The Internet is a network that can transfer large amounts of data including multimedia files, email messages, and newsgroup messages.

- Web design is all about browsers—Technologies are already expanding Web technologies beyond the browser and onto the desktop as well as to other devices. For example, Adobe’s Rich Internet Applications use Flash to create a Web site that looks and functions much more like a desktop, as discussed in the previous section. There are already Web-enabled connections for searching the Web built into Windows Vista. And my Palm Treo already connects to the Web to use Web-based applications that exchange data between the Web site and the Treo.

- People are patient, and they will stay on the Web site to explore—Some users are online to research, but many visitors to your Web site go there because they want specific information about something you offer. They don’t want to spend time reading through long HTML pages or clicking through a large number of links to try to find what they want.

Design

Some of my business clients have believed in the following Web design myths. My business designed several Web sites for clients who believed that visitors expected some design features listed here only to realize later that their customer base really didn’t care for it. (In some cases I had to report feedback, and in other cases I had to put my foot down, which lost me a couple of clients.)

- Designing for the Web is different from designing in other media—Yes... and no. It’s true that designing for the Web is different. You do have a different flow of information. And there are some constraints in Web design that are similar to GUI design and some that are quite different, as the previous section discussed. However, designing for the Web still means that you have to take care to prepare. You still have to interview users and learn about the behaviors they’re looking for to make your Web site user friendly.

- Animation and a lot of graphics are a necessity—The Web provides opportunities for you to add graphics and animation, but you must be polite to your users in that you shouldn’t overwhelm them with Web graphics. Like a newspaper or any other print medium, you need a good balance between graphics and text. Of particular note is the animated graphic, which can get your users’ attention but can also serve as a distraction when the user is trying to see something else on your Web site. Too many graphics or animated graphics can also distract users from what you want them to see on a Web site. In the end, the user will become annoyed and likely won’t return to your site. Further, overuse of cutting-edge graphical technologies can prevent users of some Web browsers from using your application if those browsers don’t support these technologies.

- Background sound is a necessity on a Web site—You can embed sound files to play in the background when users visit your Web site. However, this can quickly become annoying, especially if users can’t turn it off short of turning the volume on their speakers to 0 or mute. Listening to the same melody over and over again can quickly become tiring. What’s more, if your application depends on sound, you might be excluding users from your user base who might have hearing difficulties.

- Content is all that matters in Web design—When you design for the Web, you’re not just designing Web pages that have static content that you want people to read. You’re designing a system that includes the form that information takes, the behaviors of your system and how the Web site flows from one page to another, and the content itself. And if the content is not easy to access, users will become frustrated and dissatisfied with your application.

- Presentation is the only thing that matters, not any “plumbing” behind the scenes—When you create a Web site, obviously you want your Web site to look good, all the links to work properly, and your interface to be accessible by all visitors to your site. However, after you start adding forms, scripts, or other Web application code that changes your Web site into a Web application, you need to build code behind the scenes using languages such as PHP and Java. And if the infrastructure of your site is not solid, you can risk usability problems, or worse, data or privacy loss for your users.

- Plumbing is something you can do by yourself—It’s easy to produce the visible pages of your Web site because the rules are straightforward, and if you have merely an informational Web site, usually Web pages are all you need to design. If you are designing a Web application, however, unless you have a lot of expertise in the code required to make your site transactional, you should hire qualified companies to come in and do the work for you. Even though code packages are available for things like e-commerce, you may have some integration issues with your site that you may need someone else or another company to look at. Web development is still far from trivial and should be entrusted to those who are experienced with Web technologies.

Accessibility

Your site will be available to millions of potential viewers, and those viewers have different computer setups that are as individual as they are. Therefore, it’s important to be aware of Web site accessibility myths and what the truths are.

- All I have to do is design for the most popular and most recent browser, and everyone will be able to see my site—Not everyone uses the latest version of Microsoft Internet Explorer, which as of this writing is the most popular browser with about 90 percent market share. People use a variety of other browsers on a variety of platforms that you must take into consideration. For example, you may have users who use Firefox in Windows, Netscape in Linux, and Safari in the Mac OS.

- Accessible pages must appeal to the lowest common denominator version of a browser—HTML, the language for designing Web pages, contains backward compatibility when it comes to accessibility features. The most current version of HTML, version 4.0, is supported by all major browsers, and all current versions of Web design software such as Dreamweaver and FrontPage support HTML 4.0 development. Version 4.0 of HTML is backward compatible with versions of HTML going back to Version 2.0, so you don’t need to worry about designing a Web site or application using an earlier version of HTML. However, the same isn’t true for many other web technologies outside of HTML. For example, there are numerous differences in JavaScript in various Web browsers.

- Accessible pages have to be text only—You can still have different colors, graphics, and other materials such as multimedia clips on your Web site. However, you need to have alternative tags, or ALT tags, attached to every graphic and multimedia object on the Web site, as discussed in more detail in Chapter 2, “Concepts and Issues.” Users should have alternate ways of using the site that do not depend on sophisticated audio or visual effects.

- Accessible pages don’t have to make graphics accessible for people who can’t see them—The Web is a multimedia environment. People who are sight impaired can still experience Web sites through accessibility features available through their operating system. If you know that you’ll have sight-impaired users visiting your Web site, you may also want to have audio links so those users can listen to features on your site.

Also note that roughly 25 to 30 percent of users don’t load images on their Web sites for reasons that include sight impairment, bandwidth issues, concerns about viruses, and frustration with the prevalence of image-intensive commercial advertisements. Although the use of broadband connections like DSL and cable is growing, there are still quite a few people accessing the Internet through dial-up connections, and of those people, you’ll probably have quite a few who don’t want to spend the time waiting for an image to load. Having an ALT tag attached to a graphic or multimedia object will give your users an idea of what you’re trying to communicate through the graphic or object.

Web Postures

In Chapter 7, “Designing a User Interface,” you learned about the postures in a desktop GUI application. To review, there are four types of postures in a desktop GUI application (Cooper and Reimann, 2003):

- Sovereign—An application that keeps the user’s attention for long periods

- Transient—A task-specific, need-based application that the user uses occasionally

- Daemonic—An application that usually doesn’t interact with the user and runs in the background

- Auxiliary—An application that exhibits the characteristics of both sovereign and transient applications

Do these postures also apply to Web sites? Yes, but because Web sites have different functionality, they have different names. What’s more, different types of Web sites require different postures.

Different Types of Web Sites

There are three different types of sites you can create for the Web. These sites have different names from the postures for GUI applications (Cooper and Reimann, 2003):

- Informational sites—These do not require complicated transactional features. Informational sites are as advertised: they provide information that the user can search for by clicking on links to go to other pages within the site, and these pages contain more information. The MSNBC News Web site is an informational site, as shown in Figure 8.2.

Figure 8.2. The MSNBC News Web site is an informational site.

- Application sites—These require a significant level of data transactions using scripts that manipulate that data behind the scenes. The user will never see what level of data is being transacted. The transactions can be as simple as the user filling in contact information in a form and sending the data in an email message or as complex as a full-scale e-commerce system where data has to be stored in a database and data on the site must be updated dynamically. The Amazon Web site, shown in Figure 8.3, is an application site.

Figure 8.3. The Amazon Web site is an application site.

© Amazon.com, Inc. or its affiliates. All Rights Reserved.

- Portal sites—These provide information for the user about things happening with the company and links that tell the user how to get somewhere else. These sites are connected to services such as AOL and Yahoo!, as well as portals that are available through the browser, such as the Netscape portal for the Netscape browser, as shown in Figure 8.4, and the MSN portal for Internet Explorer.

Figure 8.4. The Netscape portal site.

Netscape and the “N” Logo are registered trademarks of Netscape Communications Corporation. Netscape content © 2007. Used with permission.

The types of postures for each of these sites depend on the type of Web site you’re creating—some sites include more than one posture (Cooper and Reimann, 2003).

Informational Sites

Informational sites have both sovereign and transient posture characteristics depending on what you’re displaying.

An informational Web site has a sovereign posture if there is detailed information displayed on the user’s screen. Unfortunately, it’s difficult to know what sort of display resolution the user will use to view a site. The standard maxim for Web sites is to design for a size slightly smaller than Super VGA resolution, or 800 × 600 pixels. This ensures that everyone can see the text on the screen, but it could also mean users will have to keep scrolling down to read all the information on the screen.

If screen resolution is a significant concern, make it a point to ask your users during the interview process what screen resolution they use. Then you can determine the screen resolution from the primary persona. Otherwise, if you design your site for a larger resolution and users complain, you will have to spend time and money changing the site or potentially lose current and prospective customers.

If your primary persona doesn’t access your site often, your site has a transient posture. A good example is the Microsoft Windows Update Web site, which users don’t visit often unless they need a critical update or they want to see about installing noncritical updates for their Windows installation.

Good navigation is always a rule, but it’s especially important for transient sites because people don’t want to keep clicking the same links to get to their desired page. Many sites use cookies, which are small text files that Web sites place on your computer, to store your site preferences and load them the next time you access the site. For example, the Google News site allows you to personalize your opening Google News Web page. Google saves the information in cookies so that your personalized Google News page appears the next time you open the site.

Application Sites

Application sites can also have different postures, but because the interaction is more complex, the postures can differ depending on the needs of the primary persona.

For example, if the application is for consumers only, such as an e-commerce site that customers visit on an occasional basis, the site must include elements of sovereign and transient postures. E-commerce sites need to have sovereign elements because they usually have a variety of products to choose from, and people want to compare different products and read about what each product does. Application sites also have a sovereign posture if the user uses the application site regularly, as does the owner of a business who needs to check the inventory on his Web site every day.

However, the site must also reflect a transient posture to users because they generally don’t visit application sites every day. The transient posture on an e-commerce site includes a shopping cart that is always visible (sometimes with the current items in the cart listed as well), good navigational aids, as well as the use of cookies to tell the system what the user last viewed or making suggestions about similar products.

Cooper and Reimann (2003) suggest that transient Web applications should follow the same guidelines as transient GUI applications. However, they list several other guidelines you should be aware of:

- Clearly telegraph the application site’s functionality. Make affordances obvious and visible, such as the ability to find a certain type of clothing by clicking a link on the page. You can also give hints if necessary, such as a reference in the text or in the ALT text that’s associated with a photo. For example, if you have a photo of a sweater, as soon as the user moves the mouse pointer over the photo, she’ll see text that reminds her to click the Sweaters link to find more sweaters.

- Make the application site simple, direct, and to the point. Remember that users have set goals when they visit your site, and you need to tell the users just enough so that you meet their needs. If you become too verbose or try to add too much functionality, you’ll lose their interest.

- Make the application site fit in the users’ mental models and flow in the context of the Web site. When you develop the site, pay close attention to the workflow of your Web site and what your users expect the site to be. For example, if your site is a clothing store, be sure that the site constantly reinforces the fact that you can buy different types of clothing in your online store. If you have a different application from your store site that isn’t in line with what you’re trying to sell, you run the risk of making that link look like an advertisement. Web users have long been desensitized to Web ads, particularly banner ads that you’ve probably seen at the tops of pages.

- For e-commerce sites, employ transactional features as much as possible to reduce confusion. This is especially true of the checkout process, which is usually the most confusing and frustrating part of e-commerce. However, if you carefully create the flow and design of the process to include clear input, instructions, and feedback, as well as a clear start-to-finish process, you will have happier customers and a more successful e-commerce site.

- Plan carefully regarding access to user data. Most transient Web applications can’t save user data on the client side, so if you need users to log into a particular area on your page (or to the remainder of the Web site), make this functionality as seamless and obvious as possible. For example, you may have a user ID and password so the user can log into the preferred customers’ page.

Fortunately, modern Web browsers (like Internet Explorer) help users by allowing them to save their user ID and password information so they will only have to enter the ID without having to remember the password. You may also want to provide information to your users about creating a secure password. - Make application sites with a sovereign posture nearly indistinguishable from similar desktop sites. The Rich Internet Application is one such example; with it, people can develop Web interfaces using Flash that look and behave similar to the user’s desktop. Like desktop applications with sovereign postures, a sovereign application site should consist of full-screen applications with controls and objects that the user can easily access to gain as much control over the interface as possible.

Web Portals

You probably have heard about “portal” Web sites, which provide a lot of information in one location. There are several different types of portals you may encounter on the Web (Cooper and Reimann, 2003):

- Consumer oriented—These provide access to content and functionality related to a specific topic or a group of topics. For example, the MSN.com portal (shown in Figure 8.5) has content related to news and weather headlines as well as links to other services such as the Web search feature at the top of the page.

Figure 8.5. The MSN.com portal.

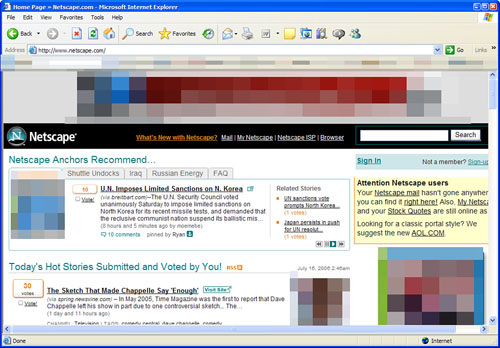

- Enterprise portals—These provide information you can access for company information and business tools. For example, Web site hosting services allow you to log into your site remotely using an enterprise portal, an example of which is shown in Figure 8.6. After you log in, you can make changes to your site such as add an e-mail address or look at your statistics.

Figure 8.6. An enterprise portal for accessing a hosting service control panel.

- Environmental portals—These are Web sites where actual work is done. The portal that the Web site hosting service offers is an excellent example. The hosting service environmental portal shown in Figure 8.7 allows hosting customers to make changes to their service information by accessing tools that are represented by icons and menu choices.

Figure 8.7. An environmental portal for the hosting service.

Consumer and enterprise portals usually have a transient posture, because users go to the portal to find something they want, and as soon as they click on the link they want, they’re out of the portal. Within an environmental portal, however, you’re running a number of individual program elements simultaneously. These elements also have two postures: auxiliary and transient.

Most environmental portal elements have an auxiliary posture because they usually present sets of information that the user wants constant access to. For example, in the case of a Web site hosting service portal, the user will want access to her list of e-mail addresses. The environmental portal also includes transient elements that are used for short periods when the user needs it, such as submitting a support ticket to the technical support staff at the hosting service.

Why You Need Web Engineering

Web design is not just the design of Web pages, but the design of a Web system. This holistic approach reflects that Web design now involves Web sites interacting with Web applications. Web applications involve many transactions based on the interactivity between the visitor and your site. If you require this sort of work, you need a Web engineer to work with your designers to create an integrated, holistic system that works the way you and your visitors expect.

“Back-End” Programming

Web sites provide information through a Web browser and connect to other sites using links. Web applications, on the other hand, can produce Web pages that change depending on the input they receive from the visitor. That can include the number of shirts the user wants to order from your e-commerce site or the type of catalog the user asks for when she fills out an online form requesting more information from your company.

Much of the functionality of Web pages happens out of the visitor’s sight. Web application programming is also referred to as back-end programming. The front end is what the user actually sees, while the heavy lifting goes on in the back. Web pages and Web services work in a two-way, content-to-transaction relationship. The content can drive the transaction, such as on an e-commerce site, but the transaction can also drive the content.

Form Processing

One example of content driving the transaction is a Web site form, an example of which is shown in Figure 8.8. This form contains one or more text boxes that allow the visitor to type information into the boxes and then click a button at the end of the form to send the form information to the server. If the back-end programming considers that the visitor completed all appropriate fields satisfactorily, it processes the form and sends it to its intended recipient(s) via email.

Figure 8.8. An example of a form.

The transaction can also drive the content, because after the Web site has completed the transaction, the programming directs the posting of a thank-you message on the Web site.

One other variable that you must be aware of is security. All current browsers provide pretty good security so people can’t hack into the form and steal credit card numbers and other sensitive information. When you work with a Web engineer, be sure that he is up-to-date on security issues and programming—or find another engineer who is. You can have only one Web page that takes sensitive information, but if this Web page is not secure, visitors will not give you their information. If visitors do give you their information and that information is stolen, you could face serious legal issues.

Databases

Back-end Web programming commonly interfaces with databases, which hold information about data that the Web visitor may be interested in. For example, an e-commerce Web site usually contains information about products for sale. The database then drives the content, because the Web site displays the number of products available as well as how many products are available for purchase (or if the company is sold out).

The visitor can order one or more products and specify how many of each product to order. After the visitor enters his shipping and credit card information, the database updates the information, processes the order, and tells the Web site to display a thank-you page. When the database changes, the back-end programming automatically changes the quantity of products available and may or may not reflect this updated quantity on the Web site.

Web Standards

Like a user interface, a Web interface must be consistent across all pages of the site, because that consistency gives your visitors the impression that the site is part of a unified whole. (Yes, it’s that holistic idea again.)

Colors and Text

Colors and text are still limited by browsers. Computer users have different fonts installed on their computers. They also display different ranges of colors. For example, my computer can show more than 4 million colors on the screen, but another person’s computer may only be able to show 65,536 colors. Although browsers and Web design software such as Adobe’s Dreamweaver let you create any colors you want in your Web site, you should design your Web site for the least common denominator when it comes to text and graphics. That denominator is the Web-safe set of several common fonts and a set of 256 colors that all browsers can display. Also, be careful to avoid colors that might have cultural implications, or colors that might cause a problem for colorblind users.

Also, design your site so that visitors can read the text on your site properly. What looks cool to you may look to a visitor like you’re trying to give her a seizure. It’s important to keep the issues of contrast and simplicity in mind. For example, you should have a black font on a white background for the best contrast. You should also consider what font is the most readable. Many people find the Arial font to be more readable onscreen than Times New Roman.

What’s the point of designing to the “least common denominator” for your visitors? Keep in mind that you want your site to look the same across all browsers; differences could result in your site not looking the way you intended. For example, if you use a font not on your visitor’s computer, the visitor’s computer may show a different font that wrecks the spacing on the site—or it may not show the site at all. If the visitor’s computer can’t view one or more of the colors that you have on your site, that computer will display a color that it thinks is the next best thing—and your visitor may be surprised at the color he sees. For example, if you attempted to use a red color to indicate a serious condition, but the color substituted by your computer does not convey the importance, you won’t get your message across.

Also, be sure to use tasteful colors and fonts. If you use a lot of bright colors, colors that don’t coordinate well together, or fonts that are whimsical and unprofessional, it can reflect on the perception that your users have of your company.

Graphics

If you’ve done any Web surfing, chances are that you’ve seen examples of bad graphics on a site. The telltale signs of bad use of graphics can include one or more of the following:

- Flashing text, a flashing block of text, or both. These are generally used in banner advertisements that users have grown accustomed to ignoring.

- Animated graphics that distract the user from looking elsewhere in the text.

- Too many graphics within an area of the page that not only distract you from looking at any text on the site, but result in frustration because all the graphics compete for your attention at the same time.

- Graphics that are pixelated and jagged.

Your site should avoid using your graphics badly. Above all, however, your site should have only enough graphics on the page to communicate to the user effectively.

In some cases, you may only need one graphic for your company logo. If you have an e-commerce Web site, it should have a limited number of graphics spaced out so the user can see what the product is but not be overwhelmed with so many graphics in one area of the page. Amazon.com is a company that does this well on its home page. The Amazon site has numerous graphics hawking various wares, but the graphics are spaced well apart and combined with text, and the text and graphics blocks are separated by a healthy amount of white space.

Navigation

Your site should be easy to navigate—meaning that if you don’t have links to other related pages of your site readily available so visitors can get back to where they were, your visitors will become frustrated and leave. If you’re selling things on your Web site, users leaving can mean lost business for you. And if you don’t have visitors on your site, what’s the point of having a Web site in the first place?

Bread Crumbs

As part of having good navigation, your site needs to include links that take users back to the home page or a higher-level page (such as a shopping cart) on each subpage. These bread crumbs can be links that appear on the page, as shown in Figure 8.9. Alternatively, you can have a navigation bar or area that appears the same way on each page for your visitors’ use.

Figure 8.9. A bread crumb on a Web site that leads the user back to the home page.

The Four Rules

You should adhere to four rules when you design a Web site so that your site is as usable as possible: keep your site simple, keep it consistent, keep it current, and keep navigation to three clicks.

Keep It Simple

From the previous section, you probably got a good idea that your Web site should be as simple as possible, whenever possible. There are exceptions, as I’ll detail in the next section, but you should make your layout as easy as possible. Also, remember from Chapter 7 that the readers’ eyes in Western countries follow from left to right, and from top to bottom. However, this may not always be the case, so my advice from Chapter 7 applies—you should perform a user and task analysis of your users to find out where they’re coming from and what they’re looking for on your site.

Keep It Consistent

As with a user interface, your Web site interface must be consistent across all pages. If your Web site suddenly changes its look, users may become confused and think that they’re on a completely different site. In the case of your user interface for a software application, such a tactic would result in calls from other customers. In the case of a Web site, visitors will simply leave and never return. To help keep sites consistent, it’s beneficial to have one person responsible for reviewing the look of all the pages on the site.

Keep It Current

If you don’t have current information on your site that keeps your customers coming back to see what you’re up to, your visitors will get bored and leave. If they see a date or language on the site that proves that the site is badly dated—and in the Web world, one to two months qualifies as dated—they will assume that there is no reason to return to your site for updated information. Or they may get the impression that your company doesn’t care about serving its customers.

Keep Navigability to Three Clicks

One of the golden rules about Web site design is the three-click rule: the user should be able to find what he wants on your Web site in three clicks. If the user can’t find the information he’s looking for in three clicks, you may need to change your Web site structure accordingly.

When Do You Break the Rules?

The rules in the previous section are not unbreakable. Sometimes you need to break the rules when they don’t suit the needs of your company or your users.

Breaking GUI Rules

You may need to break GUI rules if there are already standards in place that the organization is currently using. For example, if the company produces software that has a specific user interface that the customer is already used to or requires, you should design your user interface to that standard.

Your user testing may also determine that, although your user interface meets the specifications for the GUI, the users find the interface to be cumbersome in places. In that case, you need to determine what the users would like to see changed and determine if you can make those changes.

Breaking Web Rules

You may have so many options available that the three-click rule doesn’t apply. For example, if you have an e-commerce site, users may have to click more than three times to get to the product they’re looking for. If the site were redesigned to adhere to the three-click rule, users would be faced with a product page that would overwhelm them with choices, and they would become so confused that they would decide not to bother.

If you’re going to use a complex transaction that requires a richer interface, such as the Rich Internet Application that was discussed earlier in this chapter, many Web rules may not apply to your project.

If you have an existing company intranet that connects to a separate program, such as the Web-based component of Microsoft Outlook so you can schedule meetings and contact people from a Web application, and your Web site has to follow those standards, other Web standards may not apply to your site.

You may also need to break the rules to meet the standards set by the rest of your organization. For example, the Web site may need to look and act a certain way, and you may need to include features that already exist on the current Web site into your new Web site so that both sites appear to be the same.

Case Study: Interface Navigation Features

The database application that you’re updating for Mike’s Bikes contains a Web-based interface for easy integration into Mike’s Bikes intranet so that everyone can access the application through the Web browser. In the previous chapter, we discussed the need for you and Evan to review the entire interface to ensure that the computer (played by Evan) in the paper prototype test accurately reflects the current look and feel of visual and audio cues.

Those visual cues also include the colors and navigation of the interface. Fortunately, you have a color laser printer, so when you take the screen shots for the paper prototype test, you have full color versions of the screens available for your testers. When you add new screens for testers to look at, you and Evan also decide to use multicolor pens that reflect the colors in the pages as much as possible so the test is as consistent as possible.

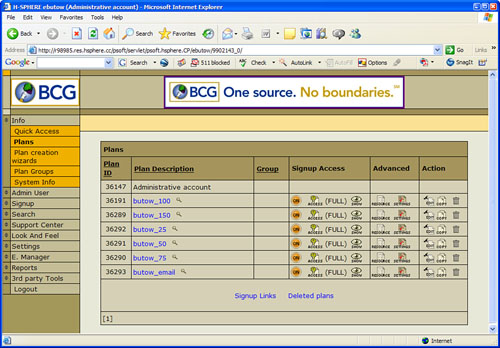

You must also be aware of the interface navigation features. The current application for Mike’s Bikes includes breadcrumb navigation on each page as well as a navigation menu button bar at the left side of the screen so the user can move to each page easily, as shown in the figure. Your new screens need to implement these features, and because the navigation bar has a new menu button for the product availability page, you need to add the Product Availability button to all the screen shots in the paper prototype test (see Figure 8.10).

Figure 8.10. The new screen with the Product Availability button.

Although you don’t need to be detailed in the paper prototype, such as making the new Product Availability menu button the same color as the rest of the buttons in the test, there are times when you will have to use a different color to make a point. For example, in the Mike’s Bikes application, you will add a new Web site Ordering button in the product table that is a different color from the other buttons. You will have to use a marker with the color to make this button (in this case, yellow) contrast with the adjacent button so that the Web site Order button stands out. Figure 8.11 is in grayscale, but you can see the difference between the lighter color and the darker color of the adjacent button, enabling the lighter Web site Order button to get the user’s attention.

Figure 8.11. The Web site Ordering button is in a different color.

![]()

The paper prototype test will tell you if the color you have chosen is acceptable to the testers. Speaking of the test, it’s time to give your test a run with just you and Evan. Then you need to prepare for the real test, as described in the next chapter.

Summary

This chapter began with a discussion of the similarities and differences between the Web interface and the GUI interface and how technology is blurring both interfaces to make desktop interfaces Web capable. Those technologies include the Java programming language, the ActiveX and PHP scripting languages, Adobe’s Flash animation software, AJAX and Dynamic HTML, and even more proprietary solutions such as Microsoft .NET languages.

Next, you learned about Web myths in terms of usage, design, and accessibility so that you can be aware of them. After each myth, information followed that dispelled these myths so you can provide truthful information if any of these myths come up for discussion during the development process.

Following that was the discussion about Web postures and the types of postures that are available for all three types of Web sites: informational sites, application sites, and portal sites. You learned that the type of Web site you create determines the type of postures you design, and the type of postures in turn (along with the needs of your primary persona) determine what features you should include in the Web site.

The section on why you need Web engineering discussed the design of a Web system and how Web sites today use dynamically generated Web pages and interactions between the front end that Web site visitors see and the back-end programming that makes the Web site functional and usable. You learned that the content can drive the transaction, such as on an e-commerce site, but it can also drive the content. One example of content driving a transaction is a Web form. The transaction can also drive the content, because after the Web site has completed the transaction, the programming directs the posting of a thank-you message there.

Web standards were covered next. You learned about the three areas of Web standards that you must pay attention to: colors and text, navigation, and leaving bread crumbs. You learned about how to use colors and text for maximum readability, and avoid certain graphics such as flashing text and animated graphics that distract the user from your message. As part of your site navigability, you learned that you should have links to other pages of your site as well as bread crumbs that take your user back to the home page or to a higher-level page.

The four rules of Web design followed: keep it simple, keep it consistent, keep it current, and keep navigability to three clicks. The chapter ended with a discussion of when to break the rules, such as if your company already has existing rules, if you want your interface to be consistent with another tool you use, and if your user testing reveals usability problems that need to be corrected in the interface, even though the correction violates the rules.

Review Questions

Now it’s time to review what you’ve learned in this chapter before you move on to Chapter 9, “Usability.” Ask yourself the following questions, and refer to Appendix A to double-check your answers.

1. What are the similarities between GUIs and Web interfaces?

2. Are GUIs and Web interfaces becoming more or less similar? Why?

3. Why do you need to know about Web myths?

4. What three categories do Web myths fall into?

5. Why is it important to know about Web postures?

6. What are the three different types of Web sites?

7. What are the three types of Web sites you can create?

8. What is an example of content driving a transaction?

9. What is an example of transaction driving content?

10. Why must you limit your color and font choices?

11. What are the four telltale signs of poor use of graphics?

12. Why should you adhere to the four rules of Web design whenever possible?

13. What is the three-click rule?

14. When do you break the Web design rules?