Chapter 5

Shifting the Focus from Communicable to Chronic Diseases

Learning Objectives

- Comprehend the widespread problems that will result from the increasing incidence of chronic diseases in the United States

- Become aware of the fact that chronic diseases cannot be cured

- Recognize that if chronic diseases cannot be cured, they must be prevented

- Acknowledge the need for partnerships in dealing with the health problems associated with chronic diseases

- Understand the necessity of increased funding for chronic disease prevention programs

The United States spends over $2 trillion on a health care system that is not producing great value for the recipients of its medical care. Despite spending all of this money every year on health care, millions of individuals become ill from communicable and chronic diseases that are entirely preventable. Shouldn't the goal of the health care system include preventing diseases in the first place rather than waiting for them to develop? If so, our health care system is failing to meet this goal while wasting precious resources that could be better spent in other areas. This has to change. The current health care system should be renamed the “disease cure system” to better reflect an emphasis on curing rather than preventing disease. The system does not adequately attempt to prevent disease, especially chronic illness. The emphasis of the health care system remains on curing disease—but once acquired, chronic diseases cannot be cured.

Brownlee (2007) argues that over one-third of the money spent on health care is wasted on treatment and testing that have very little if any effect on health outcomes for most Americans. In fact, much of this additional care may actually be very dangerous for its recipients. Making matters worse, over 50 percent of Americans do not receive the treatment they require in a timely fashion. In other words, the health of the U.S. population is not in very good shape, despite the enormous amount of resources expended. We need to begin making better decisions in regard to how we use of our scarce resources, seeking to keep people healthy rather than allowing them to become ill. It is regrettable that in the present health care system there is no reward for preventing diseases, because almost all of the money is used to treat and attempt to cure illnesses after they occur.

Where do public health departments fit into this disease-oriented system of health care? Why aren't public health departments more openly critical of the way medicine is currently practiced in this country? Holmes (2009) argues that the field of public health in the United States arose from the government's attempt to reduce the morbidity and mortality resulting from infectious diseases. Public health departments have had many successes and failures in responding to communicable disease threats. However, public health's victory over most communicable disease epidemics has fostered a feeling of complacency leading to frequent, isolated outbreaks of communicable diseases and the current epidemic of chronic diseases throughout every segment of our population. Public health departments in the United States have long focused on the prevention of disease through a system of care that treats illness as a failure of the health care system. For this reason, public health departments have used immunizations and health promotion activities to prevent rather than cure communicable diseases.

Over time the diseases have changed, and devoted servants of public health departments have seen their budgets and manpower decline as more serious public health threats have contributed to increased morbidity and mortality in the United States. The new epidemic of chronic diseases calls for public health departments to develop new strategies in order to achieve even a modest victory over these new public health challenges. However, public health departments are not prepared to consider different strategies because of their past success with communicable disease epidemics. A great deal of change has occurred since the victories over smallpox, polio, and measles some forty years earlier, beginning in the early 1970s. It seems that public health departments have been seduced by their own success; and today they still believe that their old strategies will continue to work with the current chronic disease epidemic. They are very wrong.

Herbold (2007) argues that when individuals and businesses achieve extraordinary success over time, they begin to believe that they are entitled to this success in the future—a phenomenon he calls the legacy concept. Further, they become convinced that their past success will ensure future success, as long as they employ the original practices. This is what has happened to public health departments over time: they will not even consider new ways of looking at public health problems because the ways of the past have worked so very well. We must at least think about other ways of dealing with very different types of diseases, whose costs and prevalence continue to grow. When failure continues to occur, we need to begin looking for alternate ways of approaching the problem.

Public health departments should be building on their past successes and developing the new skills that are necessary to continue preventing disease in the future. These departments need to recognize that the current epidemic of chronic diseases does not lend itself to control or curative measures. We need to develop new strategies in order to reduce chronic diseases' threat to the quality of life of our population and, perhaps, to the very survival of our health care system. The U.S. health care system and its public health departments must learn how to deal with illness before it occurs, a strategy that must be driven by disease prevention programs and a greater focus on population health.

The mission of public health departments in the United States has always been the prevention of disease. Public health departments moved away from this mission, however, when dealing with sexually transmitted diseases, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Public health departments have used a strategy with this category of disease that involved counseling and testing of infected individuals. They see this approach as the only way to deal with the epidemic, and have not considered prevention, which can only be accomplished by education at an early age. Health education efforts in this country, especially in schools and workplaces, have never received a great deal of attention from public health departments. There may have been a health promotion program offered from time to time, but never a sustained, measurable effort to educate children and employees in the prevention of disease. In the case of sexually transmitted diseases, it seemed like a better answer to locate infected individuals, get them to treatment, and then find their contacts and also treat them. This type of strategy does not prevent anything except the spread of the current infection—and there is no question that the strategy has failed, given the increasing incidence of sexually transmitted diseases. The approach will certainly not work with chronic diseases, because finding individuals with these diseases does nothing to prevent others from becoming ill.

As we have argued throughout this book, the United States is now faced with an epidemic of chronic diseases that do not lend themselves to curative or counseling and testing approaches. These diseases are unlike communicable diseases in their etiology, incubation period, prevalence, and burden to society. They are also very different in regard to the strategy required to deal with them. Although this country has had great success in controlling communicable diseases, such ailments remain a threat, and some communicable diseases like chlamydia and HIV are still increasing in incidence. This is a direct result of not using resources to prevent these diseases. Further, chronic disease rates in the United States show no signs of leveling off in the near future because of Americans' lifestyle choices. Chronic diseases are extremely expensive in terms of morbidity, mortality, and the cost of care. We must address these illnesses through education programs designed to prevent the development of such poor health behaviors as using tobacco, maintaining a poor diet, being physically inactive, and abusing alcohol.

These diseases are affecting American families; government programs at all levels, especially Medicare; businesses; insurers; and the entire health care system. This increase in chronic diseases is not a silent epidemic, but the medical community is ignoring its potential consequences. Doctors are trained to care for those with diseases, but they receive very little if any education concerning disease prevention. They then earn their living by diagnosing and attempting to cure diseases, not by preventing them—and that remains a societal problem. What is more, physicians' focus is on their patients, and not on the population. There needs to be a system of payment that focuses on outcomes not only for individual patients but also for the entire community. This is why public health departments have to work with physicians in an attempt to improve the health of the population. Halvorson (2009) points out that there is not even a payment code for insurance plans that accounts for curative measures or medical outcome. He also argues that almost 80 percent of health care costs come from chronic diseases and their comorbidities. These comorbidities involve more than one disease and also more than one doctor, making the process of treating the chronic diseases even more difficult.

It is useful to classify diseases as either communicable or noncommunicable. Communicable or infectious diseases are caused by agents that can be transmitted from one individual to another and also from contaminated foods or water, including pathogens as bacteria, viruses, and parasites, and they usually have a very short incubation period from exposure to illness. These diseases have been a major contributor to morbidity and mortality since the beginning of time. Although these diseases are still a major threat to our population, many communicable diseases—for example, smallpox, measles, polio, and malaria—have been largely eliminated. It must also be mentioned that even though we have had great success in controlling communicable diseases, we have only been successful in the eradication of one communicable disease, smallpox. In fact, many communicable diseases are actually increasing in incidence in this country because of global travel and reduced funding for public health programs.

In 1900 the leading causes of mortality in the United States were communicable diseases, including pneumonia and tuberculosis. These diseases have been replaced by such chronic illnesses as heart disease, cancer, and diabetes. Although the chronic diseases are increasing in their numbers and are capable of breaking our health care budget, we cannot let down our guard on the old and new versions of infectious diseases. Communicable diseases, like influenza, are still capable of causing enormous morbidity and mortality for our population in a very short period of time. A comparison of Tables 5.1 and 5.2 shows this very real change in the diseases the U.S. population experienced between the years 1900 and 2000. Even though there has been a shift from communicable to chronic diseases as the major threat to the health of the population, however, communicable diseases still require our attention and funding.

Table 5.1 Number of Deaths and Crude Mortality Rate for Leading Causes of Death in the United States in 1900

| Crude Mortality | ||

| Cause of Death | Number of Deaths | Rate per 100,000 |

| Pneumonia and influenza | 40,362 | 202.2 |

| Tuberculosis | 38,820 | 194.4 |

| Diarrhea, enteritis, and other gastrointestinal problems | 28,491 | 142.7 |

| Heart disease | 27,427 | 137.4 |

| Stroke | 21,353 | 106.9 |

| Kidney diseases | 17,699 | 88.6 |

| Unintentional injuries (accidents) | 14,429 | 72.3 |

| Cancer | 12,769 | 64.0 |

| Senility | 10,015 | 50.2 |

| Diphtheria | 8,056 | 40.3 |

Source: National Center for Health Statistics, n.d.

Table 5.2 Number of Deaths and Crude Mortality Rate for Leading Causes of Death in the United States in 2000

| Crude Mortality | ||

| Cause of Death | Number of Deaths | Rate per 100,000 |

| Heart disease | 710,760 | 258.1 |

| Cancer | 553,091 | 200.9 |

| Stroke | 167,661 | 60.9 |

| Chronic lower respiratory diseases | 122,009 | 44.3 |

| Unintentional injuries (accidents) | 97,900 | 35.6 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 69,301 | 25.2 |

| Influenza and pneumonia | 65,313 | 23.7 |

| Alzheimer's disease | 49,558 | 18.0 |

| Kidney diseases | 37,251 | 13.5 |

| Septicemia | 31,224 | 11.3 |

Source: Miniño et al., 2002, p. 8.

According to a 2008 report (Trust for America's Health, Prevention Institute, The Urban Institute, and New York Academy of Medicine), the threat of communicable diseases is shaped by three factors that the U.S. health care system need to take very seriously:

1. The dynamic nature of infectious diseases. Infectious or communicable diseases are constantly changing, producing more virulent pathogens or entirely new strains of communicable diseases. Because these new infectious diseases are quite often found in developing countries, they usually become epidemics before serious investigations uncover the source, spread, and incubation period. Therefore, communicable disease epidemics remain a constant threat to this country, requiring constant surveillance using the most advanced technology that is available.

2. Globalization. The globalization resulting from international trade has expanded our wealth, but it also has increased the opportunities for infectious diseases to cross international boundaries, making us all susceptible to communicable disease epidemics. This threat from globalization is only going to escalate as world trade expands along with immigration from countries that have not gained control over infectious diseases. Further, this escalation in infectious diseases imported to our country is happening at a time when we are losing many of our senior public health employees to retirement, and insufficient funding makes it difficult to attract and train suitable replacements.

3. The effects of poverty. Poverty can be the catalyst that spreads communicable diseases throughout a population at a very rapid rate. Poor personal hygiene and sanitation in many third world countries make the possibility of new epidemics of infectious diseases a very real threat that will be carried into the future.

The proper management and eventual eradication of communicable diseases could exhaust the funds currently allocated for public health departments in this country. If we add to this burden the costs associated with dealing with the epidemic of chronic diseases, it becomes clear that public health departments are going to fail in their effort to win the war against disease in this country.

We need to change how we look at resources used to combat diseases, especially those diseases that can be easily passed from person to person. We must also consider monies used to prevent or eradicate infectious diseases as an investment in preventing future infections that would cost more than the amount initially spent. In realty, many prevention efforts to combat both communicable and chronic diseases result in increased spending in the short term (Russell, 2009). If disease is prevented or postponed, however, long-term savings replace the initial costs, making the investment in prevention an exceptionally good use of scarce resources.

Public health programs that deal with the prevention of all diseases need to develop sophisticated surveillance systems, rapid detection and communication mechanisms, and new education initiatives. Those responsible for communicable disease prevention programs must have the resources required to deal with communicable diseases as early as possible in order to prevent epidemics. There is no acceptable excuse for outbreaks of communicable diseases in the twenty-first century. Unfortunately, communicable diseases have not been eradicated in our country, only controlled, because when an outbreak occurs very little attention is paid to preventing the next outbreak through health education. The CDC reports that there are still over four thousand food-borne outbreaks every year; tuberculosis has remained a stubborn problem; rates of infection for sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV, are on the rise; and outbreaks of other vaccine-preventable illnesses still occur on a regular basis (Mead et al., 2010). In the case of food safety, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has to do more to protect our foods from harmful bacteria. Foods that are infected with bacteria and toxic substances must be stopped from ever reaching production for final human consumption. This mandate must include foods produced both nationally and internationally. Again, there can be no excuse for failure in the protection of our food supply and the protection of the population from epidemics of communicable diseases in general. This is another example of investing more resources in prevention that will result in a reduction in costs over the long term.

The Challenge of Chronic Diseases

Chronic diseases pose an even greater challenge to public health departments than do communicable diseases. There is no question that chronic diseases have surpassed communicable diseases as the major threat to the health of most Americans. According to the CDC (2009a), over 50 percent of Americans are living with one or more chronic diseases, and 70 percent of the mortality in this country is attributable to chronic diseases. The CDC is very concerned about the increase in high-risk health behaviors, such as using tobacco, maintaining a poor diet, abusing alcohol, and being physically inactive, that is not only fueling the development of new cases of chronic diseases but also leading to more of the complications that result from chronic diseases over time. This is evident in the growing numbers of Healthy People 2010 objectives that have been put forth at the national and state levels of public health departments (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010a). This interest in chronic disease control is very important because much of the death and disability attributable to chronic diseases can be prevented through a broad array of lifestyle changes. This epidemic of chronic diseases is producing an enormous burden and challenge for our entire medical care system. Because these diseases cannot be cured, our current medical care system is not capable of doing very much about this epidemic—in fact, the medical care system is at a loss as to how to handle patients with these diseases, other than to treat the resulting complications. The system makes patients comfortable through prescriptions that do very little to improve their quality of life as they age and become disabled from the complications of diseases that could have been prevented in the first place. The solution to the raging epidemic of chronic diseases in our country remains a mystery to the medical community.

One in three Americans ages nineteen to thirty-four, two in three of those ages forty-five to sixty-four, and nine out of ten of the elderly have at least one chronic disease (Christensen, Grossman, and Hwang, 2009). According to Paez, Zhao, and Hwang (2009), chronic diseases increase with age, with the greatest increase occurring from early adulthood (ages twenty through forty-four) and middle age (ages forty-five through sixty-four). These figures indicate that over ninety million Americans currently have at least one chronic disease. We are currently directing very few resources toward preventing these diseases from occurring in the first place. The key to averting chronic diseases rests with primary prevention, which usually involves health education and health promotion programs.

The costs associated with these chronic diseases are capable of bankrupting our health care system as affected individuals age and develop the complications associated with most chronic diseases. These diseases usually do most of their damage to individuals as they age, causing the costs of health care to escalate over time. This is a very significant because it demonstrates the need for prevention activities that begin very early in life and continue as individuals age, which in turn highlights the value of health promotion activities beginning in school and continuing in the workplace. This revelation supports the argument for early implementation of chronic disease prevention programs. It also calls for health care professionals to develop and implement education programs to help those with chronic diseases avoid expensive complications.

The American Medical Association (2010) reports that the insurance provider Humana is bolstering its chronic disease management service in response to the increased costs associated with treating individuals with chronic diseases. Humana plans to hire 270 employees to work at its home office in Florida to coordinate care for its chronically ill Medicare and commercial plan members. These new employees will work with a multidisciplinary team that coordinates each member's care in cooperation with his or her primary care physician, pharmacies, relatives, and community. A registered nurse will be the team leader, guaranteeing regular contact with the patient. This program is designed to reduce the costs associated with chronic disease complications. This is a very good idea, but it would be a much better option to develop community-based programs to prevent chronic diseases in the first place.

The epidemiology of chronic diseases is much different from that of communicable diseases. Chronic diseases are not caused by exposure to one agent, and they are for the most part self-inflicted through the practice of unhealthy behaviors. This is a category of diseases that do not lend themselves to the development of vaccines and that cannot be cured by medication. These diseases are capable of causing tremendous disability and pain, a reduction in one's quality of life, and premature death. Because of their long incubation period it is difficult to determine the true catalyst of chronic diseases' onset. Epidemiological studies have confirmed that risky behaviors begun early in life and practiced for many years usually are found to be the major cause of chronic diseases. There are tools available for use in primary prevention and screening processes that can help either prevent or detect a disease in an early stage, when the treatment can postpone disease complications and improve one's quality of life. Chronic diseases are also preventable if individuals are educated to never begin practicing the unhealthy behaviors that are at their root. It is therefore unfortunate that the majority of providers working in the medical care system have been trained to treat and cure diseases, not to keep people healthy in the first place.

The epidemic of chronic diseases in the United States is going to have a profound effect on the financing of health care services. The increase in life expectancy of Americans is in turn increasing the duration of chronic diseases and their complications. The physical and monetary costs are going to be staggering unless this nation can devise a plan to prevent chronic diseases and their complications from developing. The tools of prevention are available through public health departments, which house the expertise in preventing disease, and public health professionals are now being called upon to provide leadership in stopping the epidemic of chronic diseases. Public health leaders will require tremendous communication skills to convince those who control resources to work with communities in preventing chronic diseases or at least avoiding their complications.

Morewitz (2006) argues that chronic diseases are a result of complex interactions among environmental, social, and genetic factors that can be prevented through lifestyle changes. Chronic diseases are also considered a much greater threat for the disparate population, which represents those with low income, minimal education and family resources, and poor living conditions. The health care system is currently investing less than 3 percent of its resources in chronic disease prevention activities. If this same type of epidemic were being caused by infectious diseases, unlimited resources would be made available to prevent the illnesses. The chronic disease epidemic has been an ignored epidemic because its victims are usually older, and the combination of aging and disease has become an accepted norm for many older Americans. There is no reason, however, why illness should simply be accepted without even an attempt at prevention.

The most distressing part of the current epidemic of chronic diseases in this country is that they can be prevented, just like communicable diseases. Both communicable and chronic diseases are not receiving the prioritization or funding necessary for successful intervention. The current model of the delivery of health care services must change, focusing resources on preventing disease rather than on curing disease—a tremendous challenge given that those who control resources in health care profit from illness. This is where the need for community partnerships as a national priority in the United States becomes evident. This is also where the need for strong leadership in public health prevention programs becomes a requirement for saving our health care system from financial destruction.

The Need for Investment in Preventing Chronic Diseases

The most important difference between communicable and chronic diseases is the role of the individual: eliminating high-risk health behaviors can prevent the development of chronic diseases, and can also circumvent the complications from these diseases if they are already present. According to Sultz and Young (2009), many individuals do not believe that they are responsible for their illnesses. This assumption may be true with many communicable diseases, but it is not the case with the majority of chronic diseases and their complications. This “no responsibility” attitude may explain individuals' lack of interest in practicing healthy behaviors and avoiding high-risk ones. Look, for example, at the change in public attitudes toward and concern about AIDS ever since the effectiveness of treatment of this disease has improved. AIDS has become a chronic disease, allowing an individual to live longer by using an array of drugs on a daily basis. Once this disease became chronic and treatment seemed to work, the fear of infection seemed to disappear, along with the attention of the media. We are a country that does a much better job of responding to an emergency than preventing one.

The costs associated with allowing chronic diseases to develop and present complications for an individual are much higher than the costs associated with communicable diseases. These differences in costs are in part explained by the fact that chronic diseases have no cure—only ongoing and costly treatment. The CDC (2009a) reports that chronic diseases account for almost 80 percent of the 2.7 trillion dollars spent on health care services this year. These diseases are taking a larger proportion of the health care budget while also entailing lost productivity in the workplace and increasing the years of potential life lost (YPLL). Chronic diseases and their complications are robbing Americans of the quality of life years, defined as years free of disease, that they could have enjoyed had they been able to avoid becoming ill.

Chronic diseases are preventable with only a small investment in programs designed to change the health behaviors of a large portion of the population. There are many proven best practices in health promotion, a number of which are available as case studies at the end of this book, that are designed to prevent or modify the high-risk health behaviors responsible for the development of many chronic diseases. There is mounting evidence that investing resources in the prevention of chronic diseases is the only way to deal with the present cost crisis in health care. TFAH (2008) argues that investing only ten dollars per person per year in programs designed to increase physical activity, improve nutrition, and prevent tobacco use could save the payers of health insurance in the United States more than $16 billion annually within five years. This represents a return on investment of $5.60 for every dollar invested. These very positive projected results need to be communicated to all communities so that they can begin to take charge of their residents' health through community-based prevention programs.

TFAH (2008) also asserts that out of the $16 billion in savings that could be realized from healthy lifestyles, Medicare would save $5 billion and Medicaid could save more than $1.9 billion. These savings are far too high for the government to ignore. It is interesting to note that these proposed prevention programs do not require medical care—only a dramatic shift toward lifestyles that encourage healthy behaviors for all Americans.

The federal government and private businesses have the most to gain by reducing the incidence of disease through the expansion of wellness programs. The federal government, through the CDC, needs to do more in the way of disseminating research and analysis supporting the return on investment available to businesses and communities. Simon and Fielding (2006) argue that public health agencies have to provide public health information of value, including cost-effective intervention strategies, to chambers of commerce, trade associations, and businesses. What is more, in each region there needs to be a public health practitioner assigned the responsibility of liaising with the business community.

Neumann, Jacobson, and Palmer (2008) maintain that there ought to be a way to measure and share the value of government public health agencies. The fact that public health programs continue to be underfunded every year is a clear indication that the public is unaware of the tremendous benefit these programs offer. Chronic disease prevention efforts represent a way for public health leaders to prove the value of their efforts by actually reducing the costs of medical care in the United States. Many individuals require incentives to develop and maintain lifestyle practices that reduce the risk of chronic diseases (Paez et al., 2009). Such incentives should be part of all health insurance programs in our country. This is an opportunity for everyone who pays for health insurance—including the government, employers, and individuals—to improve the health of the population while reducing the cost of health care. Public health departments need to take a leadership role in helping everyone understand the positive economic effects associated with wellness programs.

Our current medical care system allows individuals to become ill, and then attempts to cure that illness. Medical care developed as a system devoted to curing communicable diseases, which are usually transmitted from person to person and cured through a short course of antibiotic treatment. The providers of care in this system waited for illness to happen and then rapidly responded with medications designed to cure the acute infection. Family doctors spent little time and energy preventing the communicable diseases. The prevention of outbreaks of illness was left to underfunded government public health departments. Medical care professionals gave little thought to changing the system of health care delivery because it seemed to work so well, especially when a communicable disease was involved.

As we argued earlier, our health care system is bankrupting the country while still leaving forty-five million Americans without health insurance. Primary prevention requires the reduction in risk factors that cause disease (Turnock, 2009). If individuals do not become ill, then there will be an immediate reduction in health care costs as well as a reduced need for health insurance. In order to keep individuals well, our health care system must educate the population about how to prevent the bad health behaviors that cause disease.

Although implementing health education programs is considered one of the basic functions of local health departments, these programs have never been given a high priority or received adequate funding. Public health departments have always used their limited resources to control rather than prevent disease, in large part because of the rigidity of communicable disease programs and their funding guidelines that advocate contact tracing if no vaccine is available. This fact is evident in the lack of attention paid to implementing health education programs in school districts and workplaces. This is also evident in public health departments' strategy for dealing with sexually transmitted diseases. Proponents of the Sexually Transmitted Disease Control Program, previously called the Venereal Disease Control Program, uses all of their resources to interview and treat infected individuals and then find their sexual partners and get them treated. Personnel hired for this program are told that their only priority is contact tracing and treatment, not education to prevent infection. This has obviously been the wrong strategy, given that we never stopped the escalation of the sexually transmitted disease epidemic—it has only been controlled on a temporary basis, and most of the sexually transmitted disease rates continue to increase every year.

Frieden (2004) argues that the local public health infrastructure has not been able to transition from dealing with communicable diseases to the more dangerous chronic diseases. This is primarily a result of many public health officials' attitude that public health strategies cannot be successful in dealing with this type of epidemic.

Because chronic diseases cannot be cured, the only intervention available is the development and implementation of prevention programs. This will require an expansion in the demand for health educators, who are far less expensive than physicians and take fewer years to train. Health education programs and the health educators that direct these programs have never received the attention that they deserve. The compensation for these positions is low, and there are not that many positions available at the present time. This lack of attention to primary prevention programs is about to change. The shift will occur because we as a nation cannot continue to waste precious resources on a failed system of health care that allows individuals first to develop chronic diseases, and then to develop deadly complications from these diseases.

The sheer desperation of our health care system is forcing it to shift to an emphasis on disease prevention, which requires community populations to reduce their high-risk health behaviors and replace them with healthy ones. This change will require more health education programs in schools and workplaces as our country attempts to expand prevention efforts and reduce the need for the cure of chronic diseases.

The prevention of disease in our health care system seems to begin and end with the use of vaccines to prevent illnesses. Health education programs are almost nonexistent in our school systems, and we are allowing our young to develop unhealthy behaviors that lead to the onset of chronic diseases later in life. It would seem that investment in the prevention of illness would be the number one priority of a modern health care system. It would also seem that businesses would have seen the value of healthy workers long ago and would be doing everything possible to keep members of their workforce free of disease and productive throughout their working years. Yet this has not been the case because the reimbursement system compensates for illness rather than wellness. Physicians and hospitals are paid for activities aimed at curing illness rather than preventing illness from ever occurring.

Prevention includes interventions designed to reduce or slow the advancement of illness and disability (Goetzel, 2009). The problem is that there are no incentives in place for prevention efforts to flourish. The health care system does not make money if people remain well. It is only when individuals become ill that the system prospers. This has to change if we are ever going to solve the major problems of health care delivery in this country—problems produced by chronic diseases, which cannot be cured, only prevented.

The 2010 Affordable Care Act has responded to growing recognition of the need for increased prevention programs in the United States. This act was the result of an attempt by the federal government to reform the current health care system in our country. Koh and Sebelius (2010) argue that this new law draws attention to the value of preventive health in the following ways:

- The Act provides individuals with improved access to clinical preventive services.

- The law promotes wellness in the workplace, providing new health promotion opportunities for employers and employees.

- The Act strengthens the vital role of communities in promoting prevention.

- The Act elevates prevention as a national priority, providing unprecedented opportunities for promoting health through all policies.

The Need for Partnerships to Combat Chronic Diseases

Public health departments have had great success in dealing with many of the chronic diseases that plague our health care system. Their prevention efforts have reduced the incidence of heart disease, cancer, and stroke over the last twenty years by focusing on reducing tobacco use, improving diet, and increasing physical activity. Their progress with reducing chronic diseases has slowed in recent years, however, because of the reduced funding that resulted from public health leaders' inability to prove the value of primary prevention to those in control of distributing resources.

The only way to deal with the epidemic of chronic diseases is through population-based medicine. This strategy requires a movement from concentrating on individual health concerns toward devoting attention to the health of communities. Public health departments have always practiced population-based medicine because of their previous work with community-wide outbreaks of communicable diseases.

Chronic diseases are such a large public health problem that they require community partnerships to deal with the epidemic. These partnerships involve most health care providers and other health-related agencies in a given community. The escalation in the numbers of individuals developing chronic diseases and their complications is best handled at the local or community level. Because the problem of chronic diseases is too large for public health departments alone to solve, partnerships need to form among local health departments and several other community agencies in order to make a real difference in the epidemic.

Partnerships allow partner agencies to move forward when an individual agency does not have the required expertise, authority, or resources to bring about change (Bailey, 2010). This is the case with the challenge of chronic diseases that faces both public health departments and communities. As Tennyson stated in The Partnering Toolbook (2003, p. 3), “The hypothesis underpinning a partnership approach is that only with comprehensive and widespread cross-sector collaboration can we ensure that sustainable development initiatives are imaginative coherent and integrated enough to tackle the most intractable problems.” Partnerships would allow public health professionals to maximize resources by pooling talent from various organizations. Despite the different mission statements found among potential partners, there is common ground in the desire to combat the greatest public health threat to ever face our nation: every community as a whole is paying for the chronic disease epidemic in terms of lost wages, increased disability claims, higher health care costs, and a lower quality of life for large sections of the community.

Some of the community partners that are vital to any population-based community prevention program are local, state, and territorial health departments; federal agencies; health care providers and facilities; and public and private organizations, industrial entities, and academic institutions. Public health departments have not heretofore been particularly interested in working with businesses for a variety of reasons (Simon and Fielding, 2006). The public health sector and the business community have generally only encountered each other in a regulatory capacity during outbreaks of communicable disease. It is very difficult to become partners in this type of relationship. Partnerships offer great opportunities for public health departments to assume a leadership role, uniting communities in defeating the awesome challenge of the epidemic of chronic diseases. This is a starting point for the development of community partnerships in the delivery of population-based health services. Exhibit 5.1 shows many of the advantages and potential disadvantages of community partnerships.

Exhibit 5.1: Advantages and Disadvantages of Community Partnerships

Advantages of Partnerships

- Maximizing community resources

- Reducing duplication of health care services

- Gaining the support and respect of the entire community

- Increasing the chances of obtaining government and foundation support

Disadvantages of Partnerships

- Reducing the autonomy of member agencies

- Losing independence

- Experiencing potential conflicts of interest

According to Shortell (2010), there should be further discussion about partnerships developed:

1. Partnerships need to be both internally and externally aligned. Partners should achieve domain consensus among themselves with sufficient overlap of goals and should understand what is expected of the partnership by external groups.

2. The partnership should gain legitimacy and credibility within the community. Drawing on the developing literature on social capital would improve this process.

3. Partnerships can gain legitimacy by understanding their centrality in the political economy of the community. Social network concepts involving direct and indirect ties, the strength of ties, network density, and structural holes are relevant.

4. Every partner has a core competence and comparative advantage. Partnerships can fail because individual members either overestimate or underestimate their comparative advantage and misdiagnose their core competence.

5. Leadership should be explored more fully: the kind of leadership needed, the kind of partnership that can deliver it, and the stage of the partnership's life cycle that is best suited for it. The role of individual leadership versus organizational leadership should be discussed.

6. Forming a partnership has a transaction cost. The literature on transaction cost economics originally developed by Williamson may be relevant.

7. The process of selecting partners, including tradeoffs and timing, should be more fully explored.

8. Population health improvement can be perceived as simply a resource for organizations to advance their own agenda and cause.

The development and expansion of partnerships to improve the health of our community populations is our only choice if we are ever to gain ground in meeting the challenge chronic diseases pose. There are certainly risks associated with this bold strategy, and that is why a neutral participant like public health must take on the leadership role and become the catalyst required to develop partnerships for improving the health of every community population in the United States.

Opportunity to Improve the Way Health Care Is Delivered

The emerging communicable disease threat and the escalation of the epidemic of chronic diseases is making it necessary to change the way health care is delivered. Not only is the current medical care system too expensive but also, and more important, it was never designed to deal with epidemics of both emerging communicable infections and chronic diseases. These two categories of diseases require a health care system with providers who get paid to keep individuals healthy and to not allow them to suffer from illness. This system will treat illness as a failure on the part of medical professionals, resulting in lower rates of reimbursement.

Gladwell (2000) argues that change happens because of the convergence of three factors: contagiousness; the ability of small causes to precipitate a large effect; and the coming together of the first two factors at one dramatic moment, or tipping point. In public health the example of an outbreak of disease caused by bioterrorism can easily explain this concept. A terrorist group introduces a contagious agent into a susceptible population. If this agent is introduced to a large group of susceptible hosts at the same time, the tipping point will most likely be reached. A similar scenario may also be present in our health care crisis in this country: the explosion in health care costs and the resulting increase in the costs of health insurance are causing those paying the bills to demand change in how we deliver health care and to come together to cause a tipping point that is capable of shifting health care delivery in this country. This tipping point is also producing a tremendous opportunity for public health departments to take a leadership role in the transitioning health care system.

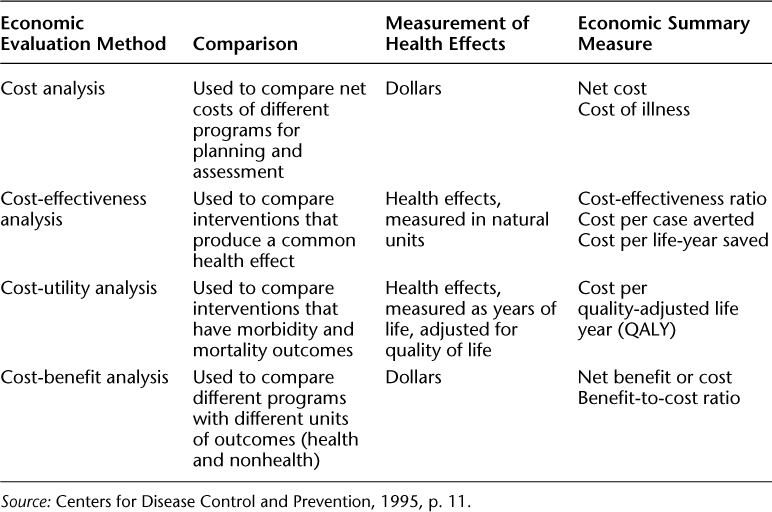

This opportunity is also presenting significant challenges for public health departments—particularly in regard to the need for improved data collection and better cost-utility analysis (Neumann et al., 2008). Public health investigators must develop core data sets that are acceptable to those involved in output measurement. How do we know when public health interventions are successful? A cost-utility analysis incorporates and measures some of the intangible benefits. Without a sustained effort to define and measure the value of public health services, the public health system will have an increasingly difficult time competing for scarce resources—especially now, with a reduced federal budget.

Figure 5.1 illustrates how risk factors precede disease, which is the cause of the escalating costs of health care. It stands to reason that in order to prevent increasing costs we need to invest resources in the prevention or reduction of the high-risk health behaviors that are the risk factors for chronic diseases.

Figure 5.1 Cause of Cost Escalation in Health Care Delivery

Table 5.3 shows four different methods the CDC has used for evaluating health interventions. The CDC proposes cost-utility analysis as the method of choice to make public health resource decisions. This type of analysis is used to compare interventions that have morbidity and mortality outcomes, measuring the health effects in terms of years of life adjusted for quality of life.

Table 5.3 Economic Evaluation Methods

The number of quality of life years a program intervention adds is a very important measure when dealing with chronic diseases and their complications. Because there is no cure for chronic diseases, the prevention of the complications from these diseases is of paramount importance in attempts to improve the health of communities and at the same time reduce the costs of health care in this country.

TFAH (2008) points out that only four cents of every dollar spent on health care delivery in this country are used to prevent the occurrence of disease, even though the research clearly demonstrates the value of investing in prevention. The rest of the money, spent on medical care, represents an enormous amount of waste. Brownlee (2007) argues that over $700 billion was spent on medical care in 2006 that offered no medical value and was capable of causing unnecessary harm to individuals. The public health system could better use this money to develop sophisticated programs designed to deal with chronic diseases. Traditional public health strategies hold tremendous potential for dealing with the chronic disease epidemic we face. The most important public health strategy involves the development of education programs that use available technology to disseminate information to large segments of the U.S. population.

Bernstein (2008) argues that our current model of health care delivery was not developed to deal with chronic diseases. He therefore proposes the use of a Chronic Care Model of evidence-based health care practices that allow practitioners to measure the outcomes of care. This model requires active participation by an informed patient who has become empowered to self-manage his or her particular chronic disease. This management is geared toward the prevention of the complications of chronic diseases, which are the real issue for those with chronic conditions. The current model of medical care focuses on curing a disease after it has occurred, with the patient acting as a passive recipient of a physician's information concerning the disease that affects him or her.

This model of an ignorant patient who lacks empowerment in his or her own health care decisions is designed to fail. In order to prevent chronic diseases, individuals have to be empowered, must avoid high-risk health behaviors, and need to recognize the possibility of acquiring an incurable chronic disease. The investment in providing the prerequisite health information to individuals has the potential for an enormous payoff—a reduction in the incidence of chronic diseases and their very expensive complications.

There are significant differences between communicable and chronic diseases that all Americans need to understand. These types of diseases vary in regard to incubation period, mortality, quality of life implications, and root cause. Our success with curing communicable diseases has led us to believe that we can cure all diseases, including chronic ones. This has become a very costly error—we are unable to cure chronic diseases, and we continue to allow some patients to experience their complications. We must correct this error if we are ever to gain control over the escalating costs of health care in this country.

Public health departments need to develop partnerships with businesses and community leaders in order to funnel valuable information to every community concerning the importance of preventing chronic diseases. Each department must appoint a staff member as a liaison between the department and businesses in order to obtain resources for the expansion of prevention programs for a given community.

The chronic disease epidemic is providing public health departments with an opportunity to lead the reform efforts necessary to make our health care system work. It is time for the emergence of public health leadership similar to that present in the early years of our successful battle against communicable diseases. The tools public health professionals use will have to change, but that shift can occur as part of retraining efforts and strong leadership development. Public health departments must exploit this opportunity through assuming leadership roles and forming community partnerships.

Affordable Care Act

Chronic Care Model

Community partnerships

Cost-utility analysis

Tipping point

1. Name and explain the major differences between communicable and chronic diseases.

2. What special competencies does the health educator require in order to work effectively with community partners?

3. What are the advantages and disadvantages of community partnerships in dealing with the epidemic of chronic diseases?

4. Explain the use of the Chronic Care Model in dealing with the epidemic of chronic diseases.