Chapter 10

Developing an Outcomes Orientation in Public Health Organizations

Learning Objectives

- Discuss the benefits of an outcomes orientation for public health organizations

- Identify the core functions and essential services of public health organizations

- Identify the major components of a continuous quality improvement process

The quality of public health organizations has become an essential part of a national effort to reduce health care expenditures and improve the health outcomes of individuals and community populations in the United States. Quality public health involves the degree to which policies, programs, services, and research increase desired population health outcomes and assure conditions in which people can be healthy (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2008). Health outcomes are indicators of how healthy an individual or a community is. Two types of health outcomes are frequently used to report on health: how long people live (mortality) and how healthy people feel while they are alive (morbidity). Access to quality and affordable health care has proven to be inadequate when addressing the health problems plaguing the U.S. population. The current status and impending onslaught of chronic diseases will result in tremendous suffering and erode the quality of life for many. This may be the greatest challenge for public health during the next decade. Members of minority populations and groups that have been marginalized based on socioeconomic status will continue to bear the burden of early death due to chronic diseases. Public health organizations can prevent many incidences of disease, injury, and early death by addressing the underlying causes of diseases. Tobacco use, obesity, alcohol and substance abuse, a lack of physical activity, poor nutrition, and risky sexual behavior are commonly known risk factors that contribute to morbidity and early mortality.

In addition to providing adequate public funding to quality public health organizations and supporting policies that are proven effective in reducing risks and improving rates of mortality and morbidity, supporting quality experts and advocates in the role of assisting public health organizations with methods that are aimed at improving community health outcomes is an important strategy to ensure a healthy nation. Good stewardship of public health funds by public health leaders is guaranteed when public health organizations make progress toward improving community and national health outcomes. The use of proven continuous quality improvement methods that require public health professionals to measure performance, link changes in services and operations to desired outputs and outcomes, assess intervention results, and design and redesign the public health system on an ongoing basis are all part of the journey to transform U.S. public health organizations into outcomes-based service providers. This chapter is about refocusing local public health organizations, particularly governmental local public health agencies (LPHAs), also known as county or city public health departments, on outcomes by implementing continuous quality improvement processes.

Quality Nexus of Public Health and Health Care

The nation spends over $2 trillion annually to treat Americans suffering from preventable injuries, infectious diseases, and such chronic diseases as cancer, diabetes, and Alzheimer's (Trust for America's Health, 2009). Transforming the U.S. system of health care and public health into a system that not only treats diseases and injuries but also addresses their principle causes is a crucial part of solving the current health care crisis. Although the United States has the highest per capita health care spending in the world, its health care system is far from the best in a number of measures of healthiness (for example, infant mortality and obesity rates), and is far behind its peers in developed countries.

During the past two decades, quality improvement experts and organizations have led efforts to increase the benefit to patients from health care services and to reduce the harm that patients experience. The Institute of Medicine (IOM, n.d.) defines quality in health care as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.” The IOM's publication (1999) of To Err Is Human, a report on the serious flaws in the U.S. health care system that result in deaths and injuries to hospital patients, placed the U.S. health care system under the microscope. What followed was an expansive effort to improve health care, guided by six areas for improvement: safety, effectiveness, patient centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, and equity. Recently, public health agencies in a number of states, for example Florida and North Carolina, have adopted, studied, and adapted quality improvement methods, such as Six Sigma and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement's Breakthrough Series (IHI, 2003; Six Sigma Online, n.d.).

Today a number of health care organizations throughout the United States can point to improved health outcomes as a direct result of implementing and evaluating changes to improve their systems of care with the highest likelihood of success. The Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group (NNECDSG, 2009) is a regional interinstitutional organization that provides information about the management of cardiovascular disease in Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont. The group maintains and studies patient data from all coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), percutaneous coronary intervention, and heart valve replacement surgeries. The NNECDSG also monitors and studies clinical outcomes from these procedures, tracks outcomes by region, and develops prediction models to assist patients and their doctors with making the best decisions about cardiovascular health care. Finally, the group compares and uses outcomes from each participating hospital, such as CABG mortality rates, cerebrovascular accidents, and returns to the operating room for bleeding, to continuously improve institutional and regional cardiovascular disease treatment across the northern New England region.

The goals and tools for quality improvement in the health care industry have been developed through the combined efforts of multiple public and private organizations, including the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, the National Committee for Quality Assurance, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, National Quality Forum for Health Care Measurement, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, and a number of hospitals and provider groups. In the process, health care has been evolving away from a disease-centered model toward a patient-centered model (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2002).

Notwithstanding this massive effort, most consumers are still dissatisfied with the U.S. health care system. A random survey conducted on behalf of The Commonwealth Fund Commission on a High Performance Health System found that 80 percent of consumers agreed that the U.S. health care system needed fundamental change or a complete rebuilding (How, Shih, Lau, and Schoen, 2008). A report by the National Committee on Quality Assurance (2008) indicates that the quality of health care in the United States reached a standstill in 2008 after years of steady improvement. It will no doubt take decades to remedy the quality issues associated with the vastness of the American health care system. Instituting quality public health services that “principally address the fundamental causes of disease and requirements for health, aiming to prevent adverse health outcomes,” will help to accelerate the goals of improving population health and reducing the ever-increasing and excessive costs of health care (Public Health Leadership Society, 2002, p. 4).

Quality improvement efforts in the public health system have taken a somewhat different path than those in the health care system. During the past twenty years, the public health sector has been clarifying its mission, vision, core functions, and essential services to a nation that has “lost sight of its public health goals and has allowed the system of public health activities to fall into disarray” (IOM, 1988, p. 19). In 2008 the Public Health Quality Forum was established and organized under the leadership of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). This forum developed the Consensus Statement on Quality in the Public Health System (HHS, 2008), which clearly stated, for the first time, a uniform definition of quality in the public health system, modeled after the IOM's definition (n.d.) of quality in health care. Quality in the public health system was defined as “the degree to which policies, programs, services, and research for the population increase the desired health outcomes and conditions in which the population can be healthy” (HHS, 2008, p. 2). The Consensus Statement identifies the optimization of population health as the ultimate goal of quality improvement by public health organizations. Optimizing the health of the population is an outcomes-based approach and is aligned with the mission of public health put forward by the IOM: “Public health is what we, as a society, do collectively to assure the conditions in which people can be healthy” (IOM, 1988, p. 1).

Focusing on Core Functions and Essential Public Health Services

Gaps in performance that threaten the public's health and security continue to exist within the public health system, according to the IOM and other analysts (IOM, 2002; Turnock, 2009). Developments that clarified mission, core functions, essential services, and the definition of a public health agency have brought changes to local public health systems. However, minimal evidence exists to demonstrate whether these changes have resulted in improvements in the organizational performance of local public health systems or whether population health outcomes have improved. Paul Juran, a prominent leader in the field of quality improvement, declared that every system is perfectly designed to achieve exactly the results it gets (cited in Berwick, James, and Coye, 2003). The current U.S. public health system is designed to achieve exactly the results that are in existence today. Improving performance and outcomes requires changing the practice of public health professionals and the organizations that support the delivery of public health services.

Public health experts and analysts have promoted a variety of methods to change the public health system and improve performance. The American Medical Association (AMA) completed the first reported review of public health practice in 1914. The goal of the review was to describe services of state agencies. Findings by the AMA indicated a lack of focus on preventive health services. A scorecard was developed to rate state agencies according to their performance of preventive health services, a method the American Public Health Association (APHA) adopted in the 1920s in its appraisal form, a self-assessment tool designed to obtain information about official and unofficial public health services within metropolitan areas. The evaluation schedule for local public health followed in 1943 was also voluntary. APHA's Emerson Report of 1945 listed six basic public health services: vital statistics collection, communicable disease control, environmental sanitation, public health laboratory services, maternal and child health services, and public health education (cited in Turnock and Handler, 1997). During the late 1980s and early 1990s the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) helped to identify local public health services and infrastructure measures in its National Profile of Local Health Departments (cited in Corso, Wiesner, Halverson, and Brown, 2000). NACCHO continues to conduct national periodic studies of governmental local public health agencies, establishing a comprehensive description of infrastructure and practice (National Association of County and City Health Officials [NACCHO], 2005a).

The Institute of Medicine's 1988 report on the future of public health was the impetus for a new round of performance reviews for public health organizations and instituted the core functions of assessment, policy development, and assurance as major components of public health practice. Public health experts around the nation believed that operationalizing the core functions in order to assess their performance across local public health systems was an important step in changing the practice of public health. The Public Health Practice Program Office of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) assembled a group of public health professionals from a number of national public health organizations and the Health Resources and Services Administration of the federal government to identify the tasks associated with each of the three core functions (Corso et al., 2000). The ten organizational practices (Exhibit 10.1) they identified “describe a continuum of problem solving activity, cycling from problem identification to evaluation in order to redirect interventions” (Turnock et al., 1994, p. 479). A number of LPHAs used the ten organizational practices intermittently to evaluate their performance of the core functions. In 1990 the Assessment Protocol for Excellence in Public Health (APEXPH), sponsored by NACCHO, was the first self-assessment tool to incorporate the core public health functions identified by the IOM in 1988 as well as a community health improvement process that assessed community partnerships (CDC, 1991).

Exhibit 10.1: Ten Organizational Practices

1. Assess the health needs of the community

2. Investigate the occurrence of health effects and health hazards in the community

3. Analyze the determinants of identified health needs

4. Advocate for public health, build constituencies, and identify resources in the community

5. Set priorities among health needs

6. Develop plans and policies to address priority health needs

7. Manage resources and develop organizational structure

8. Implement programs

9. Evaluate programs and provide quality assurance

10. Inform and educate the public

Source: Turnock et al., 1994, p. 480.

A public health researcher and endowed chair of health services research at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, James Studnicki, found that almost 75 percent of local health department resources in Florida were being spent on communicable disease programs and primary care (Studnicki et al., 1994). Today, public health agencies continue to focus a substantial portion of their resources on providing medical care to vulnerable populations, including women and children living at or near poverty levels and HIV/AIDS patients with limited access to medical services. The emphasis on direct delivery of health care services can be attributed to the era following Word War II when concern over the lack of health care for many resulted in local public health agencies' becoming safety net providers. Controversy continues over the emphasis by local public health systems on ensuring health services for the uninsured or poor while assessment and policy development activities remain limited. Turnock et al. (1994) observed similar results when they assessed LPHAs using the ten organizational practices framework. A surveillance tool with eighty-four performance measures built around the core functions was developed in the early 1990s to assess public health system performance around core functions (Miller, Moore, McKaig, and Richards, 1994). Subsequent studies showed that results from a set of four, twenty-six, or eighty-four performance indicators coincided, and each could be used successfully to predict effective LPHA performance. The four questions to predict the performance of LPHAs are as follow (Miller et al., p. 660):

1. In the past three years in your jurisdiction, have there been age-specific surveys to assess participation in preventive and screening services? [Assessment]

2. In the past year, has there been a formal attempt to inform candidates for elective office about health priorities in your jurisdiction? [Policy development]

3. In the past year in your jurisdiction, has a community health action plan, developed with public participation, been used? [Policy development]

4. In the past year in your jurisdiction, has there been any evaluation of the effect that public health services have on community health? [Assurance]

Studies conducted by Richards and colleagues report results very similar to Studnicki's—assessment ranked lowest in frequency of occurrence, and assurance ranked highest. Richards and colleagues also found that of the organizational practices in Exhibit 10.1, “Develop plans and policies to address priority health needs” and “Investigate the occurrence of health effects and health hazards in the community” had the lowest ranking, and “Inform and educate the public” had the highest (cited in Corso et al., 2000).

By the mid-1990s the leadership within public health adopted the ten essential services of public health (see Exhibit 10.2), with the following organizations playing predominant roles: the IOM, the CDC, APHA, and NACCHO. The three core functions of public health the IOM identified in 1988 are well addressed in the ten essential services, along with all of the activities from the earlier frameworks for identifying and evaluating public health performance. In addition, the task of developing a trained and competent public health and personal health workforce makes its first appearance.

Exhibit 10.2: Ten Essential Public Health Services

1. Monitor health status to identify community health problems.

2. Diagnose and investigate health problems and health hazards in the community.

3. Inform, educate, and empower people about health issues.

4. Mobilize community partnerships to identify and solve health problems.

5. Develop policies and plans that support individual and community health efforts.

6. Enforce laws and regulations that protect health and ensure safety.

7. Link people to needed personal health services and assure the provision of health care when otherwise unavailable.

8. Assure a competent public health and personal health care workforce.

9. Evaluate effectiveness, accessibility, and quality of personal and population-based health services.

10. Research for new insights and innovative solutions to health problems.

Source: CDC, n.d., p. 2.

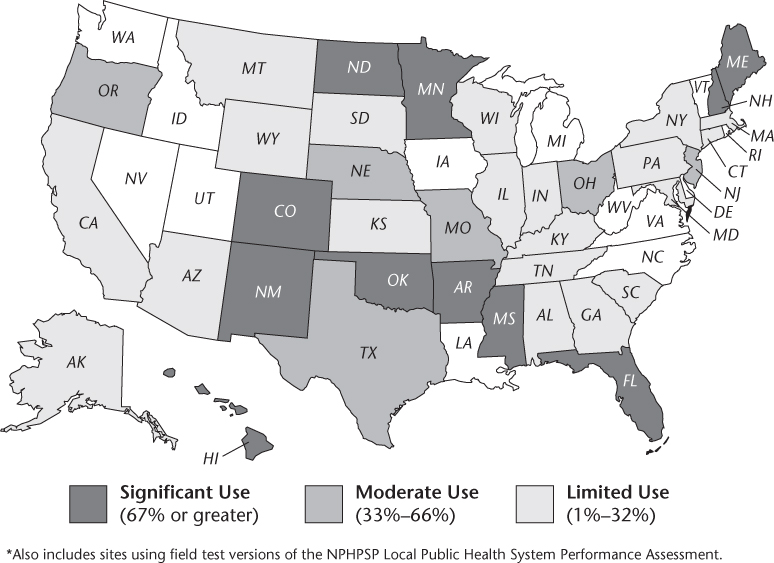

The National Public Health Performance Standards Program (NPHPSP), in collaboration with NACCHO, developed performance standards and a self-assessment tool using the framework of the ten essential services in Exhibit 10.2 for local public health systems. The NPHPSP is a voluntary effort led primarily by LPHAs to assess the performance of all key community partners in the local public health system who work to improve the public's health, including LPHAs, health care providers, academic institutions, businesses, government entities, and the media (Corso et al., 2000). The self-assessment tool asks state and local public health practitioners how well their organizations are meeting the standards. This local public health agency assessment tool includes over sixty pages of questions related to the performance of the ten essential services. The assessment process is designed to support quality improvement initiatives by identifying gaps in achieving optimal performance by state and local public health systems and local boards of health, which govern LPHAs in many states. To date, twenty-two states have used the state-level instrument. The use of the local public health system performance assessment instrument (see Figure 10.1) has varied throughout the United States: ten states report significant use, six states indicate moderate use, and the remaining thirty-four states have minimal or no use reported (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2008a).

Although the conceptual frameworks developed during the 1990s around public health practice have some merits, “none provide a well-defined theoretical framework concerning the elements that constitute and influence effective public health practice” (Roper and Mays, 2000, p. 71). Public health practitioners will need to know with some certainty that the decisions they make concerning public health services for their respective communities and regions and the resources expended to produce those services will have an impact. Public health work in motor vehicle safety, immunizations, workplace safety, promotion of safer and healthier food, and control of infectious diseases has been credited with extending life expectancy and improving health status in past decades. However, newly emerging health problems and threats, generated by the effects of chronic diseases and unhealthy environments, raise concerns about the ability of public health to have an ongoing impact in the future. The limited funding currently allocated to public health in the United States makes these decisions even more critical if we expect to see ongoing improvements in the health status of the U.S. population. Public health experts continue to refine their definitions of the essential services of LPHAs. Linking these services to improved community health outcomes will help practitioners employ evidence-based practices that are tied to the content of their work, such as increasing the percent of the population with a healthy weight and reducing health care–associated infections. A well-defined theoretical framework not only must include the services or processes necessary for great performance but also should identify expected outcomes.

Attempts to assess effective public health practice were hindered by the design of the assessment tools. The inclusion of all system partners (governmental public health departments, health care, the media, academia, businesses, and communities) in the assessment of the local public health system, although a valuable attempt to bring all key players to the table, led to some confusion as governmental public health agencies tried to identify what areas their particular organizations needed to improve. Additionally, many local public health agencies considered the essential services to be too broadly defined to describe their individual work. NACCHO recognized this dilemma, and by 2005, working collaboratively with public health experts, leaders, and practitioners around the nation, created the Operational Definition of a Functional Local Health Department (NACCHO, 2005a). This effort was considered a major step in creating a shared understanding of what any community member might expect from his or her local public health agency and was designed to foster a climate of accountability (Lenihan et al., 2007). The operational definition is based on the ten essential services and includes forty-five standards that define public health practice and community health improvement efforts. Local public health agencies that are assessing their ability to perform, for example, the first essential service (monitor health status and understand health issues facing the nation) are asked to respond to questions about obtaining and maintaining such community health data as immunization rates, hospital discharges, environmental health hazards, and rates of uninsured. In addition, a LPHA is required to assess the development of relationships with local providers and other community partners, its contributions to the community health assessment process, and its ability to integrate data from multiple sources and analyze trends and health problems that adversely affect the public's health. Little has been reported on the use of these standards by LPHAs.

Current Quality Improvement Efforts in Public Health Organizations

The disarray in the public health system's performance of services to improve the health of community populations continues across many governmental public health agencies. Evidence mounts concerning the wide variation in availability and quality of public health services in U.S. communities, such as in regard to the following (Mays et al., 2009, p. 256):

- Population-wide strategies to investigate threats to the public's health,

- Promotion of healthy life styles that prevent many diseases and injuries,

- Preparedness for man-made and natural disasters, and

- Assuring environmental conditions that reduce exposure to risks such as unsafe water, pollution, and climate change.

The establishment of core functions, essential services, and standards for local public health systems and agencies has helped public health organizations clarify their roles to the community, engage partners in an assessment process, and evaluate to some degree the performance of the local public health system and agency. From a national perspective, however, a large proportion of local public health agencies have made limited use of the national process to assess their performance of the essential services. A continuous quality improvement (CQI) process requires ongoing assessment of performance, measurement of processes to achieve goals, and a diligent review of implemented strategies and their effect on improving health outcomes. Until recently, the emphasis on improving quality in public health organizations has been primarily based on providing the ten essential services, establishing standards of performance, and instituting a quality assurance process that compares current performance levels to the standards. This approach is based primarily on improving processes. Achieving the mission of public health to ensure conditions in which people can be healthy is possible by identifying gaps in performance, selecting priority community health outcomes to be improved, choosing evidence-based strategies that address the priority outcomes, and measuring performance of the public health mission to see that changes are implemented and outcomes are improving. Improving health outcomes is the primary focus.

In 2004 momentum picked up for establishing a process to accredit public health organizations. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) convened a group of stakeholders who created a set of guiding principles for an accreditation process for local public health organizations and developed recommendations addressing the desire for and ability to implement a voluntary national model for local public health agencies (Russo, 2007). Proponents of the process believed that it would promote greater accountability and prompt more quality improvement initiatives by local public health agencies. Others worried it would be a meaningless bureaucratic exercise that would absorb resources for public health services and label organizations as malfunctioning while offering little or no help to improve (Russo).

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation launched a three-year Multi-State Learning Collaborative (MLC I, II, and III) in 2007 to explore standards in public health organizations. The goals of the MLC projects were to prepare state and local health departments for accreditation, contribute findings from the grantee projects to the voluntary national accreditation process, and foster the application and institutionalization of quality improvement methods in local public health agencies (NACCHO, 2009). RWJF believed that the processes associated with QI would help local public health agencies become more effective and efficient in delivering services and producing better health outcomes for communities (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2009). MLC III participants were asked to select at least two target areas for improvement, one from the “process” list and the second from the “outcomes” list below. The lists were developed by the MLC program team and its partners for the third year of the MLC initiative (National Network of Public Health Institutes, 2010, slide 48):

Process Target Areas

- Community Health Profiles

- Culturally Appropriate Services

- Health Improvement Planning

- Assure Competent Workforce

- Customer Service

Outcome Target Areas

- Vaccine Preventable Disease

- Reducing Preventable Risk Factors That Predispose to Chronic Disease

- Reducing Infant Mortality

- Reducing the Burden of Tobacco-Related Illness

- Reducing the Burden of Alcohol-Related Disease and Injury

Sixteen states were involved in the MLC initiative. Preliminary results from the MLC III initiative indicate that the sixteen states are using a variety of quality improvement methods, and most of the states are providing training to LPHA staff on quality improvement methods and tools. Some of the states are adding quality improvement standards to their current assessment process. All sixteen states have selected one or more of the target areas for improvement and are learning to work collaboratively across jurisdictions as they implement QI techniques. Working on common goals while learning from a variety of approaches to improving quality are core principles of the MLC III initiative.

Standards for a voluntary program for the national accreditation of governmental local public health agencies were developed by the Public Health Accreditation Board in partnership with a number of public health leaders and organizations (PHAB, 2009). Following an alpha test of the standards with two state agencies and six local health departments, a beta version of the standards for state and local health departments was launched in 2009 with two major sections (Parts A and B) identified for review and assessment of performance. Thirty public health departments are participating in the beta test. Part A includes standards for the administration and governance of public health agencies. Public health agencies applying for accreditation would be reviewed by PHAB site teams to assess their operational infrastructure, financial management systems, and engagement of the governing entity. Part B of the review is built around the ten essential services and operational definition of a functional local public health agency. To help local public health agencies prepare for the accreditation process, NACCHO developed a self-assessment tool based on its Operational Definition of a Functional Local Health Department.

Public health agencies have been exposed to many standards and performance expectations since the 1988 IOM report The Future of Public Health. In spite of all the attention given the governmental public health infrastructure by a variety of public health policymakers, researchers, experts, and leaders, little evidence exists to suggest improvement in the delivery of public health services and associated health outcomes. Wholey, White, and Kader (2009) raise questions about the wisdom of emphasizing the ten essential services framework instead of goals for specific health outcomes, such as those found in Healthy People 2010, to drive quality improvement in public health agencies. These authors express concern about whether the strong emphasis on function and services is the best method for creating effective and accountable local public health agencies. They advocate instead for a focus on content—which is the actual work of public health professionals—defined according to outcomes they seek to achieve, such as reducing tuberculosis rates or increasing rates of physical activity. Public health professionals need knowledge about evidence-based practice and CQI methods that link process to outcomes to help them achieve their public health goals of improving health outcomes. The following are some concerns about a public health initiative that is primarily focused on process—in other words, on the ten essential services (Wholey et al., 2009):

- The absence of a body of evidence to be employed as a vehicle for improving population health outcomes

- Limited research supporting the ten essential services framework as a driver of quality for public health agencies

- The use of scarce public health resources for accreditation in place of well-established quality improvement methods focused on achieving specific aims

Gaps in the Quality of Public Health Services

Conceptually and in reality, the use of the ten essential services as standards to improve the practice of public health at the local level is under scrutiny. The conceptualization of standards to guide public health performance has taken place during the past twenty years, and many in the field have expressed a strong predilection for the ten essential services. In addition to questions about the choice of the ten essential services as the basis for accreditation of LPHAs and the seemingly lackluster acceptance of the ten essential services by LPHAs around the nation, LPHAs have to face growing challenges in order to maintain their positive effects on community health. A 2004 study concluded that the percentage of adults ages fifty to sixty-five receiving routine and recommended cancer screenings and influenza vaccinations in our nation's capital was low, with less than 25 percent of the scientific sample being up-to-date (Shenson, Adams, and Bolen, 2008). In Florida, researchers found that a majority of resources within local public health agencies were used for individual health care services, even as demand for improved population-centered services increased (Brooks, Beitsch, Street, and Chukmaitov, 2009). Further, an assessment of public health practice in Georgia determined that the core business of public health in the state was not aligned with the essential services, demonstrating that “the primary drivers or determinants of public health practice were finance related rather than based in need or strategy” (Smith et al., 2007, p. 1). Lastly, a growing body of evidence reveals that public health services around the nation vary greatly in terms of availability and quality (Mays, Smith, et al., 2009). The financing of public health services along with staff characteristics contribute to this observed variation.

Following the HHS announcement on April 26, 2009, of a public health emergency caused by the swine flu (H1N1) epidemic, the ability of local health departments to communicate about the risk of H1N1 within twenty-four hours of a declaration of an emergency was analyzed by researchers at RAND, a nonprofit institution conducting research to improve policymaking and decision making for public and private organizations (Ringel, Trentacost, and Lurie, 2009). The assessment of a sample of state and local health departments' success in providing online information about H1N1 within the specified time frame revealed that forty-nine states and the District of Columbia had some information about H1N1 on their Web sites. Out of the sampled local health department Web sites, 34 percent provided some type of information or link to information related to swine flu within the required twenty-four-hour time frame. The study was limited by the absence of any in-depth review of the quality of messages on the studied Web sites. As of 2009, state preparedness funding was tied to performance on a preselected set of performance measures and standards, including risk communication. The threat of funding loss does not appear to have resulted in improved risk communication for a number of local health departments based on the RAND study. Risk communication is a critical public health responsibility and works toward fulfilling the public health mission of ensuring conditions in which people can be healthy. A possible explanation about the variability in performance found in this study may be the lack of consensus among those who are employed by local public health agencies, including agency leaders, about what public health departments do. After thirty years of defining public health and its essential services, questions remain about LPHAs' responsibilities.

In spite of the tremendous effort to define the mission and functions of public health, quality issues persist. What is becoming more apparent is that the U.S. public health system, despite a twenty-year period of increasing awareness of the importance of improving population health outcomes and public health agency performance, has neither the organization nor the incentive to comprehensively address population-centered, primary prevention health services that are evidence based or linked to improved health outcomes.

Federal Leadership of Quality Improvement in Public Health

The Office of Public Health and Science in HHS, using a consensus-building process with multiple public health system partners, released in 2008 its Consensus Statement on Quality in the Public Health System, which included a set of nine quality aims similar to the quality characteristics identified for the delivery of health care to patients by the IOM in 2001. Universal aims and indicators for improving the quality of public health services are not commonplace in public health practice. The goal for creating this set of quality aims was to promote consistency in quality improvement initiatives across all organizations providing public health services, not only governmental public health departments. The provision of a national framework for quality was deemed necessary to facilitate consistent implementation of quality improvement methods in the daily routine of public health practitioners and their organizations. All or some of the aims may apply to a single public health service or function when public health researchers evaluate current and future public health services for quality, or the degree to which policies, programs, services and research increase desired population health outcomes (HHS, 2008).

The Consensus Statement on Quality in the Public Health System (HHS, 2008) is the most recent effort to enhance and guide the goals of public health programs by defining quality for public health and identifying a list of nine characteristics of a quality public health service (see Exhibit 10.3). The statement was created under the direction of the assistant secretary for health, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the Public Health Quality Forum in partnership with multiple public health associations and leaders. The goal is to provide a national framework for quality that can be used to inform quality improvement efforts in the everyday practice of public health in LPHAs. Identifying the characteristics of a quality public health service is a first step in a national effort led by HHS to focus the governmental local public health agencies on areas to improve in order to achieve a high quality public health service (HHS, 2008). A number of professions apply quality characteristics to their industries, including education, software engineering, and air travel.

Exhibit 10.3: HHS Characteristics of Quality in Public Health

Population-centered—protecting and promoting healthy conditions and the health for the entire population

Equitable—working to achieve health equity

Proactive—formulating policies and sustainable practices in a timely manner, while mobilizing rapidly to address new and emerging threats and vulnerabilities

Health promoting—assuring policies and strategies that advance safe practices by providers and the population and increase the probability of positive health behaviors and outcomes

Risk-reducing—diminishing adverse environmental and social events by implementing policies and strategies to reduce the probability of preventable injuries and illness or other negative outcomes

Vigilant—intensifying practices and enacting policies to support enhancements to surveillance activities (e.g., technology, standardization, systems thinking/modeling)

Transparent—ensuring openness in the delivery of services and practices with particular emphasis on valid, reliable, accessible, timely, and meaningful data that is readily available to stakeholders, including the public

Effective—justifying investments by utilizing evidence, science, and best practice to achieve optimal results in areas of greatest need

Efficient—understanding costs and benefits of public health interventions and to facilitate optimal utilization of resources to achieve desired outcomes

Source: HHS, 2008.

Another purpose of this federal initiative is to demonstrate a national commitment to providing leadership and steering a course of action that results in the routine use of CQI techniques throughout all parts of the public health system, including finance, programs, management, governing, and education (Honoré, 2009). Table 10.1 depicts a proposed method for applying the national aims to identify potential gaps in quality characteristics of existing or planned public health programs. Improving the quality of services in a state office of HIV/AIDS includes a population-centered approach that routinely studies HIV/AIDS data to detect emerging trends in case rates and risk factors. Obtaining current epidemiological data from such studies is a proactive health practice that ensures any emerging risk factors are incorporated into current program design. Epidemiological studies are also important to detect trends in case and infection rates by race, gender, and age and promote equity by focusing resources on health disparities as they emerge. Planning and implementing the ABC Program (see Table 10.1) can prevent the spread of disease and promote health. Instituting a culture of CQI with the state office will help guarantee that changes are implemented to ensure success and that progress is measured and outcomes are achieved.

Table 10.1 Application of National Quality Aims for Public Health

| National AIMS for Improvement of Quality | PROGRAM: State Office of HIV/AIDS (Gage of conformity to meeting National Aims) |

| Population Centered | Routine Epidemiological studies |

| Equitable | Stratify data by race, gender, age and build programs accordingly |

| Proactive | Implementation of the HERR Program—Health Education and Risk Reducing Program Disease Investigation Specialist Program |

| Health Promoting | Implementation of the “ABC” Program (Abstain, Be Faithful, Use Condoms) |

| Risk Reducing | Implementation of the HERR Program—Health Education and Risk Reducing Program Offering of Partner Services (notifications, testing, suspect interviews, etc) |

| Vigilant | State-wide surveillance systems |

| Transparent | Reporting of data to funders |

| Effective | Implementation of national evidence-based programs |

| Efficient | Document and justify costs to identify new cases of disease |

Source: Honoré, 2009, p. 2.

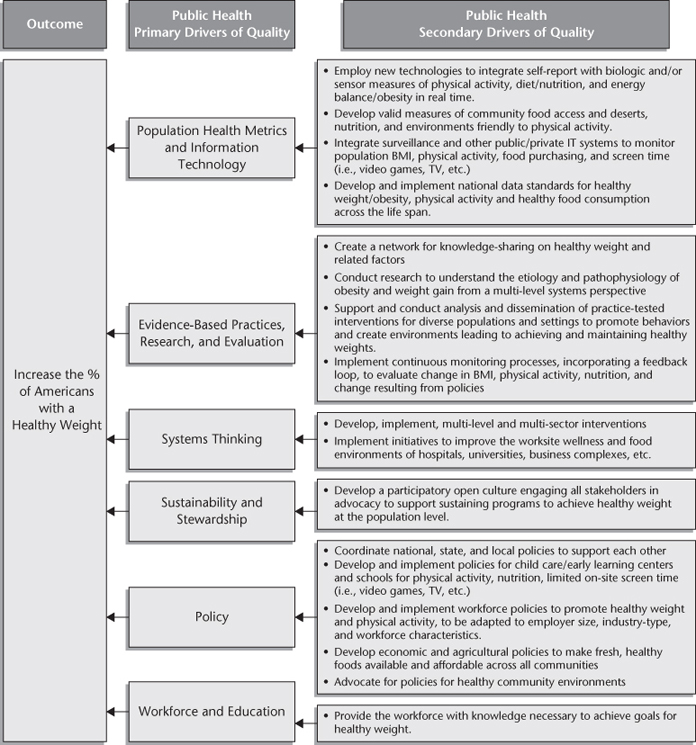

The next steps for this national initiative on quality are the development of economic and financial indicators of quality and the identification of priority areas for CQI in public health, including a core set of quality indicators and measures. HHS (2010b) published Priority Areas for Improvement of Quality in Public Health in 2010, a call to action for public health practitioners to build public health quality by focusing “on building better systems to give all people what they need to reach their full potential for health” (p. v). This report reiterates the importance of connecting the overall health of the nation to the health of individuals and health conditions in the communities in which they live (Koh and Sebelius, 2010). Accomplishing better health of individuals and communities is best achieved, according to the broad array of public health experts involved with the HHS report, by focusing on six priority areas for improving the quality of our local public health systems. The priority areas in which local public health systems are called upon to make changes for improvement include population health metrics and information technology; evidence-based practice, research, and evaluation; systems thinking; sustainability and stewardship; policy; and workforce and education. Further, HHS (2010b, p. 6) and its strategic partners have identified specific recommendations for improvement:

- Improve the analysis of population health and move toward achieving health equity

- Improve program effectiveness

- Improve methods to foster integration among all sectors that impact health (i.e., public health, health care, and others)

- Increase transparency and efficiencies to become better stewards of resources

- Improve surveillance and other vigilant processes to identify health risks and become proactive in advocacy and advancement of policy agendas that focus on risk reduction

- Implement processes to advance professional competence in the public health workforce

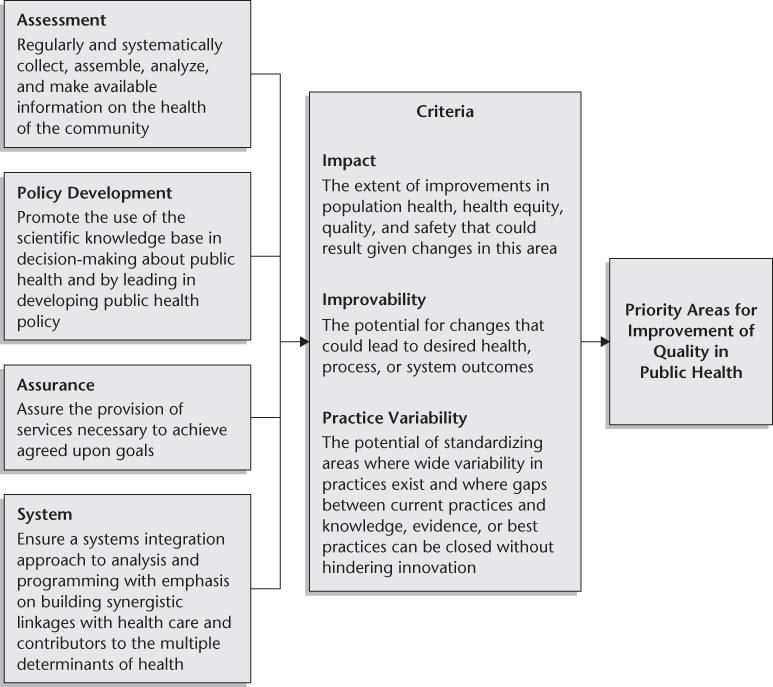

Figure 10.2 outlines the criteria HHS (2010b) used to establish the priority areas for improving public health processes and outcomes, and demonstrates the linkages between current efforts to concretely identify areas for improvement in public health using criteria and the core functions of public health established by the Institute of Medicine in 1988. The impact of these changes, the likelihood of improvements occurring, and the degree of practice variability are the three criteria that HHS applied to develop the priority areas for improvement of public health services.

Figure 10.2 Criteria Used to Establish Priority Areas (Processes) for Improvement

Source: HHS, 2010b, p. 14.

The three outcome areas identified for improvement as part of this national initiative include reducing the incidence of health care associated infections, reducing the national incidence of HIV infections, and increasing the percentage of Americans with a healthy weight (HHS, 2010b). Figure 10.3 demonstrates an example of how these priority areas for outcomes and processes can be operationalized. Primary drivers are key categories of change that have the greatest likelihood of helping us achieve our goals. Secondary drivers are collections of key processes that are highly recommended for implementation within each priority category, and they must occur reliably to achieve progress (IHI, n.d.). Figure 10.3 offers a look at the key processes within the secondary drivers of public health quality that an agency can undertake to ensure the implementation of the primary drivers of quality that ultimately lead to improvement in outcomes. In this figure we see that a primary driver for increasing the percentage of Americans with a healthy weight is the use of population health metrics and information technology. Public health professionals require data and information systems to conduct accurate surveillance of community indicators related to community food access and environments supportive of physical activity. This allows them to monitor current and future community conditions associated with evidence-based public health services in order to increase healthy weight rates in a community population. Another primary driver of quality to aid in reaching the goal, the use of evidence-based practices, includes the creation of a network for knowledge sharing as a secondary driver.

Road Map to Improve Public Health Outcomes

The leading causes of death in America are heart disease, cancer, stroke, chronic lower respiratory disease, accidents, diabetes, Alzheimer's disease, influenza and pneumonia, nephritis or nephritic syndrome, and septicemia (CDC, 2009e). Healthy People 2010 and 2020 are the nation's health promotion and disease prevention agendas developed to monitor and improve quality and years of healthy life and reduce the rates of the leading causes of death. Leading indicators, listed below, were chosen as sentinel measures of the public's health, with the goal of reducing exposure to risk factors that result in mortality (CDC, 2010b):

- Physical activity

- Overweight and obesity

- Substance abuse

- Responsible sexual behavior

- Mental health

- Injury and violence

- Environmental quality

- Immunization

- Access to health care

Quality improvement in the health care world has much to offer the burgeoning CQI efforts of public health agencies and organizations. The 2008 Consensus Statement on Quality in the Public Health System (HHS) defined quality for public health systems and listed the characteristics of quality public health services, similar to the early efforts at quality improvement in health care. An expanded definition of quality in health care has been proposed to include the “unceasing efforts of everyone—healthcare professionals, patients and their families, researchers, payers, planners and educators—to make changes that will lead to better patient outcomes (health), better system performance (care) and better professional development (learning)” (Batalden and Davidoff, 2008, p. 1). Quality public health services will need a similar cultural change across local public health agencies to reach the full potential of public health. Achieving improvement in community health outcomes requires change making and is an “essential part of everyone's job, everyday, and in all parts of the system” (Batalden and Davidoff, p. 1).

Health care data are being used in multiple ways, every day, and in all parts of the system to improve patient outcomes and health. A good example of data use, mentioned earlier in this chapter, is found in the efforts of the Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group, which uses patient registries to collect patient and procedural data, monitor outcomes in a region, and compare, for example, the practice of cardiopulmonary bypass operations in affiliated hospitals to recently published recommendations (DioData et al., 2008). When gaps are identified, hospital staff members employ CQI methods to improve patient outcomes, system performance, and professional learning and growth.

Public health agencies can follow a similar path. As already discussed, a number of tools, such as NACCHO's Operational Definition of a Functional Local Health Department (2005b) and the accompanying local health department standards, have been developed to assess performance of essential services and key administrative responsibilities. Data on health status, including those pertaining to mortality, morbidity, life expectancy, and quality of life, are generally available at the state and local levels. Data on the determinants of health found in the natural environment; the built environment; the social, political, and economic environment; biological composition (genetics, age, and gender); and individual behavior (for example, diet and nutrition or physical activity rates) are also available to some extent at the state and local levels through periodic surveys, such as the Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System; the Youth Behaviors Risk Survey; and state information systems such as the North Carolina Comprehensive Assessment for Tracking Community Health (NC-CATCH), a collaborative effort between University of North Carolina at Charlotte and state and local public health agencies in the state. The NC-CATCH system provides easy access to profiles of all one hundred NC counties, including a wide array of demographic and community health data sets, along with comparisons with peer counties in the state. In addition, the NC-CATCH “Indicator Fact Sheets” supply users with trends in indicators over time, as well as breakdowns by race and ethnicity for many health measures (www.ncpublichealthcatch.com/ReportPortal/design/view.aspx).

Deciding on an aim to improve a community health outcome, one in which a gap has been identified, is a critical first step in developing a health-outcome-focused improvement project. The gap may exist between current rates and goals set locally or by a national initiative, such as Healthy People 2010 or 2020, or it may become obvious when one county's health outcome is significantly different from that of another similar public health system and community. Considering the following questions is helpful in selecting the area for improvement, the aim:

- Is this an important health outcome for the community?

- Does a gap exist between the evidence and practice?

- Are there examples of better performance?

- What is the potential for increasing the value of public health services for the stakeholders?

- Will the benefit exceed the cost of the service?

The “aim statement” includes the intent of the project, the target population, the goals to be achieved, and the date by which goals will be attained. Engaging community members in the process of selecting the aim, as well as in developing the plan for implementing and evaluating change, promotes broader support for the CQI effort. As stated in the Principles of the Ethical Practice of Public Health, “Public health should achieve community health in a way that respects the rights of individuals in the community,…[and] policies, programs, and priorities should be developed and evaluated through processes that ensure an opportunity for input from community members” (Public Health Leadership Society, 2002, p. 4).

Selecting the changes based on evidence or the best available knowledge is vital to achieving goals for community health outcomes. CQI projects in the world of health care commonly use Wagner's Chronic Care Model (www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/ChronicConditions/AllConditions/Changes) to maintain a systems focus when identifying areas for improvement. The use of the ecological model of health, including strategies that address intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, community, public policy, and ecosystem factors, will ensure a systems approach for public health interventions that incorporates changes across multiple levels of the system rather than focusing solely on one part of the system. For example, a public health intervention not only would focus on changing individual behavior but also would explore evidence-based strategies that would have a positive impact on the social realm (establishing buddy systems to encourage physical exercise), the physical environment (developing walking trails), and policy issues (requiring food service establishments to post nutrition information on menus) affecting the CQI aim.

Planning effective programs, ones that achieve intended outcomes and account for the acquisition and use of public health revenues, follows the selection of the project's aim. Although all improvements involve change, not all changes lead to improvement. Addressing the tough issues of climate change or high obesity rates will involve systematic planning and measurement to know which interventions produce the best outcomes.

The process of improving health outcomes involves selecting changes that are based on evidence, expert opinions, consensus statements, or successful CQI initiatives. Using evidence-based programs increases the likelihood of achieving the goals to improve priority community health outcomes. Local public health agencies that proceed with services that have not been researched or reviewed for compliance with the most recent recommendations are at odds with the definition of quality that calls for “increas[ing] the desired health outcomes and conditions in which the population can be healthy” (HHS, 2008, p. 2).

Measurements of the process and outcomes are formed as part of the planning phase. Such measures serve two primary purposes: they ensure that the desired changes are undertaken appropriately (process measures) and that the program is achieving the desired results (outcome measures). Funders and stakeholders require more accountability for the use of the revenues they provide, both private and public, by insisting on quality outcome data that establishes whether a program has been successful. Developing accurate measures of the changes being implemented (the process) and the community health outcomes that form the aim statement's intent requires teamwork and expert guidance. Using criteria to develop a balanced set of measures that are reflective of changes across the system helps confine the number of metrics to a manageable and easily understood set.

Public health practitioners embracing CQI methods routinely report on the metrics through the use of tables or graphs (trend charts) in support of the goals of continuous quality improvement. CQI is only possible by ongoing review and analysis of the data. Positive and negative trends in the data reports afford the public health practitioner opportunities to ask questions about how changes are being implemented, whether planned changes are actually occurring, and how those changes are affecting the health outcome or aim of the project. Review of the data provides opportunities to improve on the work already under way or to redirect efforts toward an alternate evidence-based practice. The principal focus of local public health agency and system efforts is always on improving health outcomes in the community. Figure 10.4 is a modified version of the Shewhart cycle, commonly referred to as the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle, which is part of an important strategy for testing changes on a small scale before implementing them fully on a grander scale.

Figure 10.4 Cycle of Continuous Quality Improvement for Public Health

Source: Adapted from Shewhart, 1986.

In 2008 quality in public health was defined for the first time as “the degree to which policies, programs, services, and research for the population increase the desired health outcomes and conditions in which the population can be healthy” (HHS, 2008, p. 2). Achieving quality in public health requires a commitment to and accountability in public health programs that will improve the length and quality of life for all people. The historic emphasis on services that define the core functions of public health and the associated standards have helped identify gaps in the performance of local public health agencies and systems. The link between the performance of essential services and the achievement of community health goals is very weak, some would say nonexistent. The epidemic of obesity in our nation is some indication of the lack of attention to the determinants of health and health status by public health leaders, local public health systems, and those in charge of allocating the resources available for public health services. Developing an outcomes-focused public health initiative to address one or more of the complex public health problems of modernity at the local, state, and national levels, following the concepts of CQI, will undoubtedly help reduce the costs associated with health care and restore credibility and, ideally, funding to the U.S. public health system.

Continuous quality improvement (CQI)

Essential Services

Health outcomes

Quality public health

1. What lessons have been learned in improving health care that can be applied to the field of public health?

2. What strategies have public health departments undertaken in the United States to improve the quality of public health services?

3. Discuss the disarray of the public health system in the United States, identified by the Institute of Medicine in 1988. What evidence exists about the current state of the U.S. public health system?

4. Describe the current efforts of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to address the quality of public health services.

5. Review Figure 10.3 and explain how the primary and secondary drivers are designed to affect the health outcome found in the figure.