Chapter 3

Critical Issues for the Future of Health Care in the United States

Learning Objectives

- Understand the major problems found in the U.S. health care system

- Become aware of the ramifications of the epidemic of chronic diseases in this country

- Understand the value of health education in preventing the development of chronic diseases and their complications

- Appreciate the need for reform of the present system of health care delivery in America

- Be able to explain how the problems of cost, access, and health levels in our health care system are interrelated

The American health care system, which was the envy of the world, is not working very well. Even those who manage this enormous system are not happy with the results it has produced. In fact, it is hard to find anyone who supports its continuance in its present state, except for those who profit from the current structure. Those who control the system fear change because they are unwilling to give up their power over system resources. The word change is not in their vocabulary. Despite the resistance, however, the system must be overhauled.

Health care costs in this country are increasing at twice the rate of the costs of all other goods and services produced every year. This cost escalation continues to increase as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), and is expected to reach 20 percent of GDP in the next seven years. Fuchs (2008) argues that within thirty years the costs of health care could consume 30 percent of everything we produce in this country on a yearly basis. Sultz and Young (2009) point out that every move to control costs over the last several years by government or the health care industry has only escalated the cost increases for health services. This cost escalation of health care services is perhaps the greatest challenge this country has ever faced. Even though our bill for health care continues to rise, however, our nation is not getting any healthier.

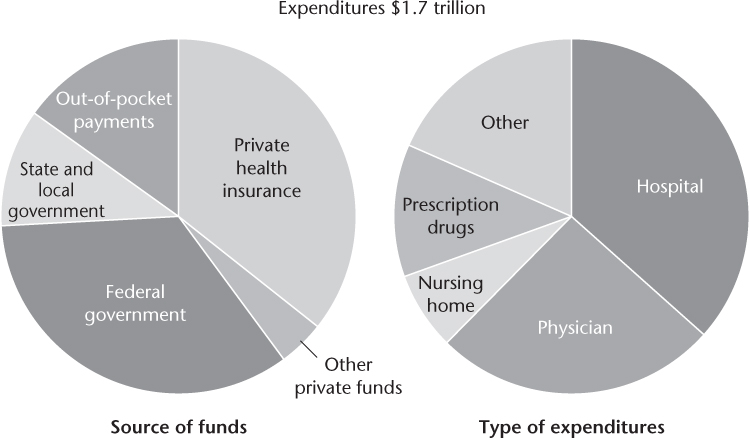

Figure 3.1 shows the various categories of spending on health care from 1960 to 2004. It is interesting to note the very rapid increase in per capita personal spending, per capita national spending, and national spending as a percentage of gross domestic product. Most health economists predict that these increases will become even larger as the costs of chronic diseases and their complications work their way through our health care system.

Figure 3.1 Personal Health Care Expenditures, 2005

Source: National Center for Health Statistics, 2007, p. 27.

The aging of Americans, the increasing spending associated with chronic diseases, the treatment of HIV/AIDS, the growing use of expensive technology, and the rising price of drugs are all factors contributing to this escalation in the costs of health care. What is more depressing is that there does not seem to be an answer to the question of how to control the costs of maintaining this most vital system. The outcome associated with a health care system should be good health. According to Emanuel (2008), over $2 trillion, representing $7,000 per person, is spent each year on a system that does not keep people very healthy. Compounding the problem is the fact that the health care system is providing too many services, increasing medical errors that claim thousands of lives every year.

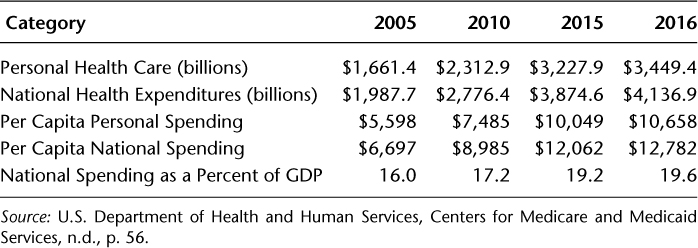

Table 3.1 illustrates the tremendous escalation in the costs of health care services delivery from 1960 through 2006, which are shown as increases in per capita spending and as a percentage of gross domestic product. Our current economic crisis is only going to make matters worse for the cost escalation of health care, because spending will continue to rise for health services despite a weakened economy. These increased costs are not sustainable.

Table 3.1 National Health Care Expenditures by Category (in Billions of Dollars), 1960 to 2006

Cost escalation is found in all parts of the health care system, but it is especially visible in the rising percentage of spending on physician and clinical services. Physicians are paid to do more even if the additional tests and procedures have little if any value and could pose great risks for their patients. We have produced a system that delivers too much health care of marginal value, which might place some patients in danger. The more we do, the more we put the patient at risk by exposing him or her to the many dangers that result from the delivery of modern medical services. According to Brownlee (2007), medical errors kill between forty-four and ninety-eight thousand people every year. It is ironic that thousands of Americans get little or no medical care, while the rest of America receives too much of the wrong kind of medical care.

Table 3.2 shows national health expenditures for 2005, with projections through 2016. National spending will continue to rise per capita and as a percentage of GDP. Despite the escalation of the costs of health care, however, we have been unable to improve the health of the population. This is because the fragmented health care system in our country does not evaluate outcomes. Rather, it concentrates on activities like physician visits, testing, and hospitalizations, which in health care are very expensive and do very little to keep people healthy, but from which many providers profit.

Table 3.2 National Health Care Expenditures for 2005, with Projections for 2010, 2015, and 2016

The cost increases for health care are affecting our government, businesses, and consumers, and even our ability to compete with other nations by increasing the prices for our goods and services. These costs have forced millions of individuals either to not have insurance or, if they do have insurance, to contribute a larger percentage of the cost of that insurance, reducing their disposable income. The health care cost crisis has an impact on every aspect of our lives, and many of us are demanding solutions from our political leaders. And it seems that these leaders keep visiting the past for solutions that have never worked and only make the current problems worse. What is more, those who profit the most from the present system of health care delivery are the ones who are being consulted for ways to improve health services in this country.

Why We Are Failing in Our Health Care Reform Efforts

Our system of health care delivery is failing to solve the main problems with the health of Americans. Fuchs (1998) argues that there are three major problems found in our health care system: cost, access, and health levels. He goes on to explain that these are not really problems but symptoms of a much larger dilemma that includes the issue of how to effectively use scarce resources. In order to solve these problems in health care, we have to completely change the way health care is delivered in the United States. This is going to require an emphasis on preventing rather than curing disease, and it will require leadership in the change process.

It seems that most people are concentrating on the problems of cost and access while paying little or no attention to the problem of Americans' poor health levels. This is a very normal response, given that most Americans pay very little attention to their health until they become ill. The medical care system in this country has never been very interested in disease prevention because the payment system for medical care does not usually reimburse efforts that are designed to keep people healthy.

As we have already noted, it is very true that costs have escalated for the purchase of health care services. The main reason for this cost escalation is that individuals are allowed to become ill in the first place. Annual expenditures on personal medical services have increased from over $35 billion in 1965 to over $2 trillion in 2011. This represents an increase from 5 percent of GDP in 1965 to over 16 percent of a much larger GDP in 2008. Despite all of these expenditures on health care services, however, this country still has over forty-five million individuals without health insurance. These are clearly very serious problems, but we must ask whether these problems are more serious than the epidemic of chronic diseases. If we can first eliminate the epidemic of chronic diseases and people remain well, the problems of cost and access will diminish. It is becoming more evident as time passes that prevention efforts may be the answer to the cost and access problems that plague our country. But how do we change the business of health care delivery? How do we change a system that is focused on curing disease into one that concentrates the bulk of its resources on preventing disease? This is where we need answers from public health departments.

According to Williams and Torrens (2008), the costs of Medicare and Medicaid, which already account for 23 percent of all federal spending, will continue to rise well into the future. The increased spending for these mandated health programs can only be controlled if their recipients remain well. It is amazing that there is so little discussion about prevention programs designed to keep people well as a way to control these costs. Even if the recipients have chronic conditions, prevention efforts can reduce the complications from these diseases later in life.

Williams and Torrens (2008) assert that these health programs cannot be allowed to grow at a faster rate than the rest of the economy, and that something drastic has to be done to tame their growth. The question becomes, then, What can be done to lower costs while simultaneously improving the quality of these popular government programs? Making matters worse, the number of Medicare beneficiaries is currently forty-three million and is expected to reach forty-nine million in the next few years, placing further strain on the system. Again, prevention efforts never seem to enter into this debate.

The problem gets worse when we discover that the rising number of aging baby boomers is only part of the predicament. The key trigger in increasing health care costs is not America's aging population, but rather the growing epidemic of obesity and the health problems associated with this weight gain (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2009a). This country ranks poorly in prevention of health problems when compared with most other industrialized nations. This becomes more difficult to explain when it is revealed that the other countries spend a smaller portion of their wealth on health care, but nevertheless have healthier inhabitants. It seems that the United States is spending its dollars on the wrong types of health care interventions rather than investing in prevention efforts. Why doesn't our country recognize the potential return on the investment in prevention programs? Everyone seems to recognize the value of good health, but that is about as far as the concept of prevention goes. Prevention as a potential solution to the health care crisis never seems to leave the discussion phase.

There is no question that the health care industry in the United States is in trouble, causing tremendous change in the way it delivers services to its customers. Health care costs continue to rise every year, and millions of Americans are losing their health insurance. The practices of unhealthy behaviors are resulting in chronic diseases, and their complications are threatening to bankrupt the health care system in the United States.

The costs associated with delivering health care services to Americans are rising faster than the cost of living every year. This difference in price increases usually indicates a problem with productivity in the sector experiencing the higher costs of production. This nation has tried price controls, managed care, and government management of such programs as Medicare and Medicaid—and has been met with only limited success. The solution to productivity problems is usually better management of scarce resources to improve outcomes. There is also an immediate need for leadership in keeping Americans healthy at an affordable price.

Despite the enormous costs associated with health care, the majority of Americans are not very healthy. They are living longer, but many are developing chronic diseases as they age and suffering the complications associated with chronic illness. Their later years have become plagued by poor quality of life, which is a result of practicing unhealthy behaviors when they were younger.

A large number of our political leaders have determined that this lack of access to health care services is the major problem with our current health care system. These politicians believe that they can solve the problems of health care delivery by instituting a national health insurance program similar to the type of government-sponsored program found in other countries. We do not wish to demean the seriousness of not having insurance for health care services, but this lack of insurance is not the biggest problem in health care that the United States faces. Access alone does not guarantee good health. Having insurance alone does not usually keep people healthy and protect the quality of their health: it only allows them to receive medical care after they have become ill.

Access to health care, usually meaning coverage by health insurance, is a very complicated issue. The access issue has become more important in recent years because most of the newly uninsured are working families who have lost their employment-related health insurance. Recent research indicates that people without health insurance die prematurely, are less productive at work, and usually receive fragmented medical care when they become ill. This fragmentation of care leads to the use of expensive medical tests that may result in increased medical errors. Health care delivery in the United States has become a series of poorly defined problems that lead to other, less clear problems, making solutions seem virtually impossible. Although most people assume that this issue can be solved by issuing some type of universal health coverage plan, there is another choice that involves keeping people healthy throughout their life.

The real problem with our health care system in the United States is that it is not prepared to prevent high-risk health behaviors that are practiced by a large number of Americans. These behaviors usually result in the development of chronic diseases after a long incubation period. These are unlike communicable diseases with shorter incubation periods and available treatment regimens: the health care system cannot offer a cure for a chronic disease once it manifests itself and becomes symptomatic in the patient, and as the individual grows older he or she will usually develop life-threatening complications from that disease.

According to the CDC (2009a), chronic diseases contribute to the greatest morbidity, mortality, and disability in this country. Cardiovascular disease, cancer, and diabetes are the most prevalent and costly—and yet all of these diseases remain preventable. Further, seven out of ten Americans who die each year do so as a result of a chronic disease. Chronic diseases are not contagious, have a long latency period, and are usually incurable. They are usually caused by human behaviors, which, once developed, are very difficult to change. Tobacco use, poor nutrition, being overweight, and physical inactivity are the main causes of chronic diseases. Once these diseases develop, they are nearly impossible to eliminate. They just continue to get worse as the individual ages, and they eventually become the catalysts in producing disability or premature death.

The way to deal with chronic diseases is to prevent them from occurring in the first place, or at the very least to postpone the complications from these diseases. In order to accomplish this, we must emphasize the prevention of high-risk behaviors through health education and health promotion programs. Those responsible for decision making in health care have never had an interest in preventing disease because the money and power are not present in prevention efforts. This is very evident in the way we train physicians, teaching them to cure disease, not to prevent disease from occurring. Population health and preventive programs have been left to poorly staffed and underfunded public health departments.

The question that we need to answer in the near future is, How do we keep people healthy in this country at a price that we can all afford? It seems very clear that a different approach to delivering health services is a prerequisite for saving our health care system from bankruptcy. This solution cannot include more government involvement, because government tinkering with the system has actually caused the severity of the current crisis. The answer must include the development of partnerships among businesses, schools, and public health departments to keep people healthy. We contend in this book that public health departments can provide leadership in prevention efforts if they are freed from bureaucratic government control. This will be discussed later in the text.

Root Causes of the Failures of the Health Care System

There are several contributors to the health care crisis in this country. They include the health insurance industry, providers of health care services, government entities, and individuals practicing unhealthy behaviors. The health care industry and providers of health care services have gained power, prestige, and profits by allowing duplication, errors, disease, and abuse of power to be a large part of the delivery of health care services in our country. Their collective power blocks change to a new model of health care delivery that would encourage wellness instead of illness for a large part of our population.

Health Insurance Industry

The most important determinant of access to health care is health insurance. The majority of Americans cannot afford to pay for expensive tests, hospitalization, surgery, and medical devices. Therefore, they pass on the risk of most costs associated with potential poor health to others through insurance. The financing of health services in the United States is done within a very fragmented system that involves public and private insurers, and it is paid for by employers, taxes, and individuals.

Insurance is protection against financial loss associated with an event. Health insurance involves the application of the principles of insurance to protect individuals from the costs associated with medical care. There are two major models for providing insurance to individuals in order to protect them from risks. These models are the casualty model and the social model. The casualty model, used for auto, fire, flood, and life insurance, forces the insured to assume some risks and losses if the insured event occurs. The social model, used in health insurance, does not require the insured to assume any risks or costs if a poor health event occurs. This model allows individuals to practice high-risk health behaviors, like using tobacco, and yet pay no higher premiums for health insurance than someone who does not practice high-risk health behaviors.

The fundamental concept of health insurance is to balance costs and risks across a large number of individuals in order to protect an individual against an unexpected health event. However, health insurance is very different from casualty insurance because of the possibility of adverse selection and moral hazard. Under the concept of adverse selection, only those who will benefit from insurance have a tendency to acquire it—unhealthy individuals are more likely to subscribe to health insurance in anticipation of extensive medical claims. Conversely, individuals who consider themselves reasonably healthy may consider health insurance an unnecessary expenditure. Because of adverse selection, insurance companies use a patient's medical history to screen out persons with preexisting medical conditions. Those perceived as high financial risks may be denied coverage or charged higher premiums to compensate; conversely, discounts may be granted to low-financial-risk applicants.

The term moral hazard refers to the reduced incentives to mitigate risks that come from having insurance. A person weighs the costs and benefits of an action, and if benefits exceed costs (which sometimes happens when insurance has shifted the risks associated with that action), he or she takes that action. In health insurance, moral hazard means that if you believe that major expenses are covered, you have fewer incentives to take measures to ensure your continued good health. In response, insurance companies attempt to reduce the risk of moral hazard by providing the insured with financial reasons to avoid making a claim, such as by employing deductibles, copayments, and co-insurance. For a society to remain healthy, incentives for both individuals and providers should encourage the provision of preventive services, including those that encourage healthy behaviors. Such incentives are usually not a part of health insurance programs.

The health insurance industry is under tremendous pressure to change the way that it does business. This important component of our health care system can no longer afford to continue to pay for damage done by individuals to their own health by willingly practicing high-risk behaviors. The insurance industry has to include some accountability for outcomes in the insurance process. McGinnis (2006) argues that health care reimbursement should encourage the delivery of preventive care services. This might involve urging third-party payers to pay more attention to preventing illness rather than simply paying bills for health problems that could have been prevented. In other words, structure a payment system that pays for wellness, not illness.

Employer-provided insurance is group insurance under which a single policy covers the medical expenses of many different people, instead of covering just one person. According to Feldstein (2007), this arrangement minimizes adverse selection by spreading the risk of an adverse health event among a large number of individuals, thus lowering the cost of premiums for those participating. For example, if one member of the group has a major health issue and the others stay healthy, the insurance company can use the money paid by the healthy to pay for the treatment of the unhealthy.

Unlike with individual insurance, for which each person's risk potential is evaluated to determine insurability, all eligible people can be covered by a group policy, regardless of age or physical condition. The insurance premium is calculated based upon the aggregate characteristics of the group, such as average age and degree of occupational hazard. This system of social insurance shares the risks, costs, and benefits of the program equally among participants, but has the danger of creating a sense of entitlement to benefits and provides little encouragement for positive health behavior. There are usually no incentives in this type of insurance plan to remain healthy.

Health insurers should be responsible for doing more than just collecting premiums and paying the providers of health care services. Their financial ability allows them to play a major role in the improvement of the health of the population, which could include offering incentives for individuals to practice healthy behaviors, such as a reduction in their insurance premium. The reverse is also true: insurance providers could increase premiums for those who practice high-risk health behaviors like tobacco use, but this is not the case in most health insurance plans.

Insurance companies could also supply public health agencies with the necessary resources to develop and implement population-based health education programs. For nonprofit health care organizations, providing community benefit is the principal standard for maintaining tax-exempt status. However, it is becoming increasingly difficult to differentiate for-profit health care organizations from the nonprofit ones, and as a result, both the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and Congress have begun to challenge the appropriateness of the community benefit standard. The IRS wants to make tax-exempt entities more accountable for their activities and to quantify the supply of community benefit provided by nonprofits.

Nonprofit health care organizations can benefit the communities they serve by funding local health department programs. This seems like a logical way for a health care organization to maintain its nonprofit status and improve the health of its community. The catalyst in bringing this about would be public health leaders' using the tax code to persuade third-party payers to provide financial resources for community health education programs. This has not happened.

Shi and Singh (2008) argue that changing patterns of morbidity and mortality should cause financers of health care to shift their emphasis from acute care to preventive care. This will require collaboration between the payers for health care and those with knowledge of prevention programs. This is a wonderful opportunity for public health professionals to provide real leadership in acquiring the necessary resources to keep people healthy, reduce illness, and lower health care costs. We must explore this opportunity for public health leadership if we are serious about keeping the U.S. population healthy.

Providers of Health Care Services

The power of the providers of health care services in America has changed dramatically over the years. The key providers of health care in the United States in terms of power and influence over the system are still the physicians and hospitals. Physicians receive less than 25 percent of hospitals' total income, but they influence most of the other 75 percent of expenditures through their decisions (Henderson, 2009). They admit patients to hospitals, recommend treatment, and prescribe medications. If we are serious about dealing with the problems in health care delivery, we must address physicians' current power and their ability to influence health.

The power physicians hold allows them to create their own demand. Sloan and Kasper (2008) argue that because physicians are paid more if they do more, there is probably too much medical treatment in this country. This excessive medical treatment may be good in some cases, but it probably results in a waste of scarce medical resources and danger to many patients. If we are ever to gain control over health care costs, we are going to have to deal with how physicians are paid. This is a very difficult task, however, because the medical market is not a normal economic market.

McLaughlin and McLaughlin (2008) point out that the numbers of physicians in specific areas of medicine usually reflect the perceptions of income potential. When you add prestige, respect, and earning potential for specialists, is there any wonder why we have a surplus of specialists and a shortage of primary care doctors in this country? There is no question that medical care has become big business. In many cases money has replaced caring in one of the most important sectors of our economy. There is too much of the wrong type of medical care, too much duplication, many medical errors, and an excess of greed. There is virtually no interest in preventing disease on the part of physicians, who are paid to do more medicine and less patient education. The profit model that health care providers in this country follow has no time for education to prevent disease. Instead, physicians have been trained to cure disease, and hospitals have expanded to provide the facilities for that process. The whole business model of health care delivery falls apart if people remain well.

The field of medicine and the education of physicians have largely ignored the value of preventive medicine, health education, and health promotion (Sultz and Young, 2009). Physicians are trained to treat and attempt to cure disease, while the disease-prevention aspect is largely ignored. The medical education system in this country has made instruction in health promotion and disease prevention a very low priority. The reasons for this include medical school faculty members' own lack of exposure to prevention education and the clear failure of our payment system to offer incentives for prevention activities to those who provide medical care.

Sultz and Young (2009) argue that recent health care reform efforts have resulted in the reduction of power and prestige of physicians and hospitals. The relationship between physicians and hospitals has also changed in recent years due to restrictions from the government payment mechanism and insurers. The physician still admits patients to the hospital, but his or her power has been restricted. Prospective payment systems require a reason for hospital admission and a diagnosis of the admitting condition, which restricts payment. Therefore, the physician's close relationship with the hospital has diminished.

Millions of dollars have been spent to increase the number of primary care doctors over the last twenty years. This increase in funding has produced more doctors, but they have situated themselves in urban rather than rural areas, and most new physicians have opted for specialization rather than primary care. Starfield, Shi, Grover, and Macinko (2005) point out that adding one primary care physician per ten thousand people produced a 6 percent decrease in all causes of mortality. This is because primary care physicians are more likely to discuss high-risk health behaviors with patients, thus providing the health education that is a prerequisite for avoiding chronic disease.

It seems clear that most physicians are not willing or able to drive prevention efforts within our current health care system. This is especially evident in that the majority of new physicians entering medicine specialize rather than providing primary care. This deficiency must be offset by increasing the number of public health professionals who provide health education programs in communities.

According to Sultz and Young (2009), the U.S. medical care system is ready to move toward an emphasis on prevention, but the finances for such a transition are in disarray. It is very important that medical practitioners begin to assume leadership roles in public education about the benefits of prevention in the delivery of health care services. In order for this to happen, however, public health departments must reach out to physicians in an effort to increase the perceived value of prevention programs as part of the health care system.

Government Entities

The rapid rise in the number of individuals without health insurance in the United States has increased the clamoring for some form of national health insurance system similar to the single-payer plan found in Canada, where taxes pay for health care for the population. The president and Congress are discussing the value of a single-payer plan. These calls for and promise of a national health insurance plan are nothing new—we have heard them before, and nothing has ever happened. Most health policy experts do not believe that more government involvement in our health care system is going to do anything but make matters worse.

Many people are amazed at the government's involvement in health care, given its history of funding health care initiatives and dictating medical decisions without having the money and the expertise to accomplish anything productive in health care delivery. The interest in health care is primarily on the part of politicians getting elected or reelected, and then the serious interest disappears. The government is currently funding almost half of the costs of health care in America, and matters have only gotten worse.

According to Emanuel (2008), 1 out of every 5 dollars of the federal budget ($580 billion) goes to pay for Medicare, Medicaid, and the State's Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP). This bill is most certainly going to continue to rise because of the aging of Americans and the complications associated with chronic diseases. These funds are used to pay for health care delivery, with very little of the funding going to prevention activities or health promotion programs.

Medicare has been called a success by most legislators. It has many satisfied customers and has the lowest administrative costs, so it seems to be very efficient in paying health care bills for those covered by the plan. Medicare only devotes 3 to 4 percent of its budget to administrative costs (Emanuel, 2008). However, the unfortunate trade-off for low administrative costs is a 10 percent rate of fraud. This fraud was never more evident than in a recent report from the New York Times, which reported that Medicare paid 478,500 claims that contained identification numbers assigned to physicians who were deceased (Pear, 2008). This entitlement program uses price-fixing to keep the enormous health care spending under control. This has not worked, however, as suggested by the fact that Medicare trustees project an unfunded liability of $36 trillion over the next seventy-five years.

A program of national health insurance, although providing access to all Americans, would do little to prevent illness. It would simply transfer payment for health services from employers and consumers to the government, which would then raises taxes to pay the enormous bill. These government-financed plans do not make us healthier so that we can lower costs—they just pay for illness in a different way. But these schemes do get votes that allow politicians to keep their employment.

Individuals Practicing Unhealthy Behaviors

The vast majority of the costs of health care delivery in this country are a direct result of chronic diseases and their complications. Currently, almost 80 percent of health care costs are for treatment of chronic diseases, and these costs are expected to rise rapidly as a result of high-risk health problems, such as obesity, and the increase in diabetes and other diseases with no cure. The incidence of diabetes is expected to double over the next twenty-five years because of the current epidemic of obesity in the United States (Bodenheimer, Chen, and Bennett, 2009). The practice of high-risk health behaviors over a long period of time causes and aggravates these chronic diseases. One of the only ways to stop these behaviors from developing is through well-developed health education programs for children that begin with the parents, continue during school years, and are reinforced in the workplace. Our current health care system ignores health education as a form of medical care. Health education programs have never become a priority for schools and workplaces, and the result has been an epidemic of chronic diseases.

Shi and Singh (2008) maintain that the epidemic of chronic diseases will eventually force the incorporation of wellness and disease prevention into the health care system. This change will not come easy to a system that makes money on illness. Further, it will shift cost increases over to individual patients, requiring them to make changes in order to comply with recommendations for health behaviors. In order for this to be successful, the patient must become educated in regard to how chronic diseases develop and, more important, how to prevent their occurrence. This is a wonderful opportunity for the expansion of public health prevention programs that have been shown to be effective when properly implemented.

The major causes of most chronic diseases in this country are a few high-risk health behaviors that are addictive to the individual, are encouraged by society, and are beginning earlier and earlier in life. A very good example is found in the increasing rate of obesity, resulting from poor diet and lack of physical activity, which is causing an epidemic of type 2 diabetes that is rapidly moving to the adolescents in this country.

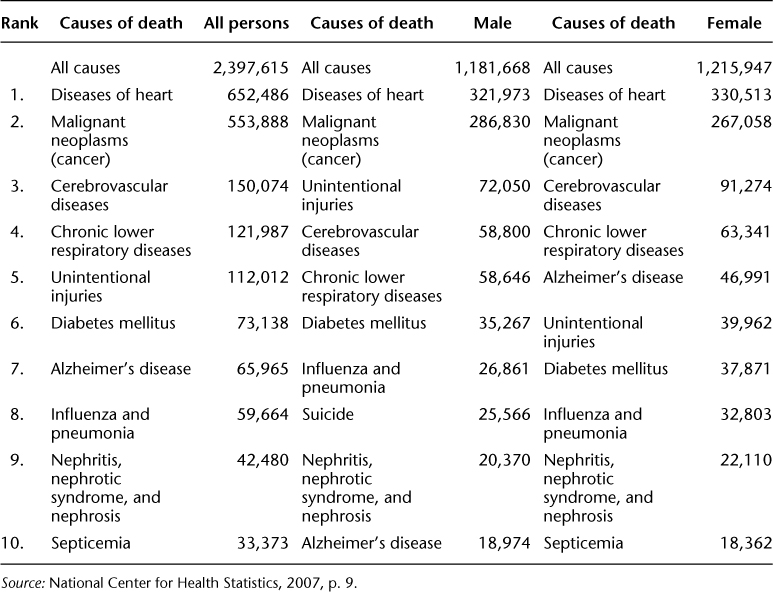

Table 3.3 shows the major causes of mortality in the United States in 2004. It is interesting to note that for the most part these diseases are preventable. In recent years, for example, there has been a very noticeable decline in heart disease: between 1970 and 2002, the mortality from heart disease declined from 362 deaths per 100,000 to 241 per 100,000 (Feldstein, 2005). The cause of this decline was most likely lifestyle changes associated with reduced cigarette smoking, reduced serum cholesterol levels, and increased physical activity. Interventions to encourage lifestyle changes that promote health behaviors do very well in a cost-benefit analysis.

Table 3.3 Ten Leading Causes of Death in the United States, 2004

According to The Commonwealth Fund Commission on a High Performance Health System (2009), a focus on prevention and improving the outcomes that result from chronic diseases could be the solution to our health care cost crisis in America. This goal could be met with the movement of scarce health care resources away from curing diseases and toward preventing them in the first place. This prevention effort will require the expansion of health education programs in schools, workplaces, and communities. These education programs can help prevent the practice of high-risk health behaviors.

Changing health behaviors is going to require a combination of broad public health incentives and health education to become part of every aspect of health care delivery (McGinnis, 2006). In order to accomplish this objective, public health professionals will need advanced training and increased funding. This will not happen until they are able to take risks and grasp the opportunities that are presenting themselves as the reform of the health care system gets into high gear during the next few years. They will also need to receive the leadership training they greatly need to bring all of the necessary prevention partners together.

There are many other less obvious causes of the failures of our current health care system. They include:

Increase in Lobbyist activity

Whenever the government has large amounts of money to spend in a given area, there is an increase in interest groups' involvement in how that money gets distributed. These interest groups include many of the associations that represent health care providers, such as the American Medical Association, the American Hospital Association, and third-party payers like Blue Cross. This phenomenon is very evident when interest groups use their economic resources to shape opinions on ways to improve the health care system in this country. Their recommendations also increase the power, influence, and, ultimately, income of their members. It must be noted that lobbyists and special interest groups do absolutely nothing to improve the health of Americans. This interest group involvement will virtually eliminate healthy competition that can bring the consumer higher-quality and lower-cost health care services. “But who cares,” we might say, “it is the government paying the bills”…until we realize that we are the government, and all of us are paying those bills.

The End of the Primary Care Physician

The primary care physician should be the health educator for the patient. This type of doctor is concerned with keeping his or her patient healthy, which requires a major emphasis on prevention. As previously noted, preventing disease does not benefit the medical care sector in this country. Physicians and hospitals in the United States get paid for doing more, not for doing less. This is the major reason why primary care doctors do not command a high salary; this is also why new doctors avoid primary care. There is currently no monetary incentive at work in health care delivery to keep individuals healthy. Physicians have found that they can have a higher salary and live a more comfortable lifestyle by becoming specialists rather than general practitioners. The specialist does not have the time or the motivation to educate his or her patients about the dangers of practicing high-risk health behaviors.

According to Starfield et al. (2005), there is lower mortality from disease in geographical areas with more primary care physicians. Therefore, increasing the supply of primary care physicians has a positive effect on communities' health. Sadly, the number of physicians choosing primary care has diminished.

Epidemic of Medical Errors

Medical errors, especially in hospitals, represent a well-known problem that has received very little attention from those in power (Sultz and Young, 2009). In many instances physicians and hospitals are reimbursed for making the error, and then reimbursed again for rectifying the error if the patient lives. Types of errors include diagnostic and treatment errors, surgical errors, drug errors, and delays in treatment, to name a few. It is frightening to know that one of the major causes of medical errors was miscommunication among health care professionals. Brownlee (2007) points out that a lack of cooperation among the players in the current health care system is one of the major reasons for the epidemic of medical errors. Up to ninety-eight thousand patients die each year from preventable medical errors (Institute of Medicine, 1999). This is another opportunity for public health leaders to intervene.

Minimal Political Appreciation of Public Health Activities

Public health leaders have never done a very good job of marketing their many success stories to the legislators funding their departments. They are frightened by the media, unless they are given the green light to speak freely when asked questions about sensitive topics. The result is that many people think of public health as part of the welfare department, and don't really care if the sector's funding is increased or even reduced. One of the missing skills of public health leaders has been the ability to work with the public and legislators through the media in an effort to convey how important public health departments' contributions are to the improvement of the U.S. population's health.

To be successful in helping people change their high-risk health behaviors requires time and resources. Many of these behaviors are addictive and will take intensive, time-consuming interventions to change. People want to know how much it is going to cost to correct these behaviors. The other question that is frequently asked is why more resources are not dedicated to preventing high-risk behaviors from developing in the first place.

Solution to the Problems in Our Health Care System

The solution to our array of health problems must begin with an honest attempt to stop diseases before they begin. This will require the development of partnerships and the leadership of public health agencies in the improvement of the health status of the vast majority of Americans.

Businesses and Employers

Businesses across the country are realizing that they can increase worker productivity and reduce their health insurance costs by keeping their employees healthy. Productivity diminishes when an employee is unable to come to work because of illness or disability. The environment of the workplace can have a major—and often negative—influence on the overall health of the workers, and requires much greater study in order to protect the worker from injury, disease, quality of life issues, and premature death. The average worker spends the most productive years of his or her life in the workplace, and if that worker's health is affected in a negative way, he or she has an overall negative payoff for all that hard work. There is nothing more important than personal health. Although some economists attempt to place a monetary value on life, there does not seem to be much interest in putting a price on the quality of life, especially when this quality begins to diminish because of injury or disease.

There are still too many Americans becoming disabled, developing chronic diseases, and reducing their quality of life in later years as a direct result of their work environment. There is a real need for the expansion of time-tested public health programs, including those that provide information about chronic diseases and their prevention in the workplace. The starting point will be improving the methods of gathering data concerning workers' health. These should encompass all health data, including statistics on such chronic diseases as heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and other incurable conditions with high medical costs that affect both employer and employee.

Although the workplace has been shown to be very dangerous for many workers in many occupations, over the last several years the nation has made significant improvements in the health of working people. There is much more work to be accomplished, however, as employers are asked to assume a greater responsibility for the future quality of life of their employees.

The quality of health care services is becoming a very serious component in controlling both the outcomes and the costs of health care delivery. Those with the responsibility of paying for health care in the United States are starting to demand that providers reduce errors in the delivery of medical services. Further, businesses are capable of playing a key role in reducing these costs while simultaneously improving the health of their employees through the development of workplace wellness programs.

Rather than seeking one big fix for our ailing health care industry, we believe that success can be achieved through small, continuous, well-thought-out, and incremental changes that keep the focus on the customer or the patient. The workplace is an ideal location to provide health information to a very large segment of the U.S. population. This can be accomplished by dedicated individuals who already possess the requisite public health expertise to improve the health of all workers.

Innovation in Health Care Services Delivery

Innovation entails a new way of doing something, and may be incremental or radical. When business models fail, leaders usually innovate and come back with new ways of achieving their goals. Our health care system has failed in keeping us healthy at an affordable cost. This fact is very hard to sell to those in power in health care because they are so very impressed by the strengths of the current system that they are blind to its very obvious shortcomings.

Our current health care system is ineffective in that it cannot provide evidence that what it is doing is actually working. The system breeds inefficiency through overuse and unbelievable duplication of services, thereby wasting valuable resources. Hospitals and doctors are paid to do more rather than to keep people healthy. Christensen, Bohmer, and Kenagy (2000) argue that it is time for the application of disruptive innovation to health care delivery in the United States, which entails using unexpected new programs that shake up the current way business is conducted. Disruptive innovation is actually a new model of doing business that capitalizes on the opportunities presented by a changing environment.

It seems that applying this concept to health care is not all that difficult if we start with the belief that the health care system should be keeping people healthy, not using scarce resources to cure those who become ill. The catalysts for this disruptive innovation are information technology and patients' involvement in their own health. This changing model of the way we deal with our health will disrupt one of the largest industries in our economy, providing a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for public health departments to provide leadership in designing wellness programs for the nation. The only missing link in this process is the leadership development within and empowerment of our public health departments.

New Model of Health Care Delivery

There are those who believe that somehow health care is different from other businesses in the United States. This is true because of the nature of the health care business, but this is no excuse for not trying to improve the delivery of health care services. This delivery process needs to be evaluated by those implementing the new approach and developed through the use of business analysis. There needs to be accountability for the enormous quantity of resources that are inefficiently used to create less-than-stellar outcomes.

As discussed in Chapter Two, Herbold (2007) argues that most businesses that are failing to produce results have been seduced by their own past success—a phenomenon he refers to as the legacy concept. He has noticed three very negative factors present in failing organizations that follow the legacy concept: a lack of urgency, protective and proud attitudes, and an entitlement mentality among employees and business leaders. These elements are evident in most of our large health care organizations in the United States. They not only revel in their past successes but also believe that they are entitled to provide medical care in America even if their services cost more than they are worth. They have become convinced that they can even cure death if given enough resources.

Notice the key word in the last sentence: cure. You do not hear the word prevention, because there are very few if any economic returns associated with prevention. Therefore, the health care system dedicates very few resources to preventing anything. Herbold (2007) asserts that there is a need to change the focus from an emphasis on curing disease, which has been continued for years with little impact on good health outcomes, to an emphasis on preventing disease. The American health care system is the best in the world, but it is not keeping people healthy. It allows individuals to become ill even though there are enormous resources available that could have prevented their illness at a much lower cost. It is a wonderful collection of health resources that have been focused on the wrong outcomes. This needs to change.

The lack of focus on prevention does not seem to be deliberate or the result of any medical conspiracy. The fact that the American health care system has been so successful has made its leaders incapable of even considering a change in focus. The system was born and grew up dealing with communicable diseases that could be cured. These diseases have been replaced by chronic diseases that cannot be cured and are responsible for major health complications as time passes. Although the diseases have changed, the system has refused to change with them because of its past successes. This is truly an example of the legacy concept at work.

Herbold (2007) also argues that businesses that achieve success begin to believe that if they continue doing business in the same way they are entitled to future success. This sense of entitlement leads companies to block change, even when their current business processes are failing. The legacy concept will usually cause businesses in the for-profit sector to go under. This does not happen to entities in the nonprofit sector as long as they have access to some continued source of funding. This is especially true for the health care system in the United States.

Members of the health care sector claim that business is done in a certain way because that is the way that they have always done business. If health care delivery were not subsidized by the U.S. government and employers, however, this type of attitude would result in health care providers going out of business. It makes little sense to support a system of health care delivery that waits for individuals to become ill before the system responds. The system should be preparing individuals to remain well and thus avoid illness. Instead, this system has successfully managed to avoid pressures to change the way health care is delivered—it is broken and refuses to allow any type of plan for repair.

The old system has failed to deliver cost-effective care for a number of years, and there is a real need to change the way we deliver health care services to Americans. Unfortunately, there are many who demand a shift to universal coverage, which would be funded, for the most part, by the government. But the government is already funding one-half of the health care bill with Medicare and Medicaid, and both of these programs are in financial trouble. It seems obvious that more government involvement in health care delivery is the last type of change needed.

Many health policy experts touted managed health care as a new model of health care delivery over twenty years ago, expecting that this new model would eliminate waste and reduce the costs associated with delivering health care to most Americans. In retrospect, this new model increased costs and in many instances reduced the quality of care. We cannot afford more incremental tinkering with the largest sector of our economy, especially by individuals who profit from the change whether it is successful or a complete failure. There is a need for both real discussion about how best to restructure the health care system and time to evaluate new models of health care delivery that could work.

The medical establishment in this country has always feared and resisted the words innovation, change, and new ways of delivering health care. Physicians developed the current model of health care delivery, and these same professionals are reluctant to give up their power to others—including other doctors and medical personnel—with respect to creating their own demand. Almost all businesses in this country have had to make changes in the way they do operate in order to survive. Health care has been the exception to the business model and impervious to business cycles because it is considered a necessity that we must have no matter what the cost.

It is not that those responsible for delivering health care do not know how to be innovative. Instead, they do not want to change the way they do business, and there are currently no incentives to change. Christensen et al. (2000) argue that the phenomenon of disruptive innovation would require health care organizations to look for ways to reduce the cost of care by making it easier for customers to access that care. But this type of change will also upset the way business is done, hence the resistance to innovation in health care delivery.

Those responsible for keeping the population healthy need to employ the new and inexpensive technology that has been shown to improve health in order to facilitate the delivery of health care to all parts of the country. This type of technology uses the Internet to share health education programs with large segments of the population at little or no cost. The old business model in health care was designed to help people return to wellness after they suffered illness. Once reimbursement for disease management and preventive care becomes widespread, the problem of access to health care will be lessened, because wellness will become the new business model for health care. Once we pay for wellness, those paying for health insurance will embrace and expand the new model.

There are many people working in health care who actually view technology as an enemy that is driving up health care costs. To these individuals, technology is a cost of doing business rather than a solution to the problems in our health care system. This is because of the way they define technology as an expense rather than an investment and their inability to see the secondary effects that usually result from the adoption of such new technology. For businesses in America, for example, new technology has the secondary effect of empowering consumers, once this technology becomes widespread and customers better understand it and become more comfortable in its use.

Another modification of the business model of health care delivery must be a change in the reimbursement process to a pay-for-performance model. The current system of reimbursement pays for input but does not even remotely correspond to health care outcomes. A large number of outcomes are very poor, including medical errors, wrong diagnoses, inappropriate testing and hospitalizations, and focusing scarce resources on curing diseases that cannot be cured. And, as discussed earlier, providers quite often get reimbursed for poor work, and then get reimbursed again for correcting their own mistakes.

Business models in most industries recognize the need for a company to regularly improve its product and delivery of services. Intense competition pressures businesses to innovate and pursue quality in order to survive and grow. These competitive incentives have never really been present in the health care industry, in which government regulations concerning the payment for health care delivery (for example, the implementation of prevention programs) usually prevent innovation and competition under the rationale that the health care system is somehow different from other business ventures. These regulations serve to protect the inefficient and discourage new ways of delivering health care.

Health care organizations need to look at continually making small changes rather than always considering the big changes, all while keeping a constant eye on the patient, or customer. Physicians' relationships with their patients are also a critical component in the new world of health care delivery. The doctor is still one of the most important players in delivering of quality health care in this country and must, therefore, assume a leadership role that will require better knowledge of all parts of the delivery process. New physicians also need to receive more training in preventive medicine while in medical school, along with continuing education in ways to keep individuals well.

Public Health as a Potential Solution to the Health Care Crisis in America

In his book Hot, Flat, and Crowded, Friedman (2008) discusses how a green revolution can renew America. He points out that when dealing with the new “energy-climate era” we need new tools, a new infrastructure, and new ways of collaborating to solve our environmental problems. We can apply Friedman's arguments to the case of the health care crisis our country faces. If public health departments choose to take the leadership role in helping America become healthy, they will need new tools, a new infrastructure, and, most important, a new way of collaborating with the various power players in the evolving health care system.

A primary goal of public health departments is to enhance the health in human communities and assure the conditions in which those communities can remain healthy (Holmes, 2009). Achievement of this goal would solve the bulk of the major problems found in our current health care system. However, although public health professionals have the expertise necessary to resolve these problems, the American health care system overall was never designed to prevent illness and promote wellness. Further, the patient—the consumer of health care services—has been given a passive role in maintaining his or her health status. The physician, who is more knowledgeable about the value of health services, has been assigned the responsibility of deciding what is needed to keep the patient healthy. The problem with this approach is that the patient has to know when to see the physician, which requires that patient to be educated about disease and how it can be prevented. Unfortunately, the patient has not been prepared to assume this role.

Public health departments are usually government-funded agencies that deal with the health of community populations rather than the health of the individual. Shi and Singh (2008) argue that public health has always been separated from medicine due to fear that the government will interfere with the delivery of health care. This is very unfortunate because collaboration between the public health and medical care systems could improve the health of the population. Both medicine and public health suffer from the legacy concept of thinking that their way of improving health is superior, and both have become very comfortable in how they go about their work. Both block change and continue to live on past accomplishments, with minimal success in solving our country's new health problems.

Our health care system has always undervalued prevention activities (Satcher, 2006). This point is supported by the fact that less than 3 percent of the money spent on health care in this country goes to population-based programs. It is interesting to note that many of the greatest gains in better health over the years have had very little to do with treating illness, resulting instead from health promotion programs that attempted to change the high-risk health behaviors of community populations. Such community-based health programs are usually developed and delivered to communities by public health agencies.

McGinnis (2006) argues that one of the most important issues in health care today is getting public health and medicine to form a real partnership. Physicians have struggled to consider anything other than treatment of disease as a logical way to deal with patients. Also, as these medical professionals have tended increasingly toward specialization, they have become further removed from the teachings of public health. At the same time, public health departments have been reluctant to engage with those delivering medical care, except for brief legal encounters over specific disease problems. These interactions have usually been power displays rather than collaborative efforts. Both the medical care system and the public health system share equal blame in this lack of unity to improve the health of the U.S. population. The disconnect between these two powerful forces must be replaced by cooperation in working toward goals that are larger than either one.

Chronic diseases are responsible for one-third of Americans' being disabled or experiencing severe limitations on daily living activities (Siegel and Lotenberg, 2006). Yet the vast majority of Americans do not even recognize these enormous health problems, and most individuals blame the aging process for disabilities and limitations in daily living rather than behavior-induced chronic diseases. Siegel and Lotenberg point out that even those working in public health are not well-equipped to deal with the challenges of addressing the multiple causes of chronic diseases, improving social and economic conditions, and reforming social policy. Nevertheless, they are the ones who are able to provide the leadership necessary to bring other community agencies together in a united effort to reduce the incidence of and complications from chronic diseases.

It is very difficult to see what public health departments do on a daily basis. If these agencies prevent disease from happening through their efforts, there is often nothing tangible that can support a claim to their effectiveness. And even if the accomplishment were to become visible, how would agencies be able to prove that their efforts were responsible for that success? It could have been caused by any number of random occurrences.

Satcher (2006) argues that the increasing epidemic of chronic diseases has triggered the escalation of health care costs and decreased the quality of life for many aging Americans. This former surgeon general offers a prescription for good health that requires no medication. Instead, he recommends moderate physical activity, a diet that includes fruits and vegetables, avoidance of toxins like tobacco and alcohol, and responsible sexual behavior.

There is a need for leaders in public health to take advantage of the opportunities present in the current health care crisis. The future of health care delivery in this country is being shaped, and if the public health sector wants a seat at the table, it is time to embrace these opportunities and assume a leadership role in the change process.

The solution to the chronic disease epidemic is not to be found in the medical care system or in public health departments (Bodenheimer et al., 2009). This epidemic will require collaboration among health educators, schools, the media, and health care organizations to promote a culture that encourages the practice of healthy behaviors. This epidemic has provided the opportunity for public health departments to fill a leadership vacuum in order to contend with the culture of high-risk health behaviors that has grown in this country.

Public health departments are facing both opportunities and a threat as a result of the health care crisis. The opportunities are found in their ability to improve the health of the public. The threat lies in the demand for public health departments to provide more services with the same or fewer resources. This book is about how public health departments can respond to this need for public health leadership as our new health care system evolves over the next few years.

The American health care system costs too much, is not available to a very large number of citizens, and is failing to keep many Americans healthy. What is more, all of these problems are getting worse each year. Clearly there is a need for immediate change, or the best health care system in the world is going to self-destruct.

Because costs and access are dependent on population health, it would seem that the answers to these problems are found in preventing illness and reducing the complications from our current epidemic of chronic diseases. In order for this to happen, our health care system has to change, and begin to espouse more widely the public health approaches designed to keep the population healthy. This is not an easy task, but it can be done.

Practitioners from the medical care and public health systems must begin to form partnerships. This will require leadership from both sectors in order to move beyond distrust to collaboration in order to develop programs to keep people healthy rather than attempting to cure them after they have become ill.

New incentives are necessary to get the major contributors to the health care crisis—insurance companies, employers, the government, health care organizations, and consumers—working together. Once again, this is going to require leadership rather than management of scarce health resources. Further, the leadership effort must begin with those organizations that have successfully used public health skills in the past to prevent high-risk health behaviors. It is time to change from a curative model to a prevention model of health care delivery in this country.

There are two major problems in moving prevention programs to the forefront. The first is that of how to market the prevention success stories to those making health care expenditure decisions in this country. The second involves determining how to eradicate the legacy concept in public health departments. The elimination of these problems requires the emergence and subsequent development of leadership in the U.S. public health system.

Access

Adverse selection

Cost

Health insurance

Health levels

Moral hazard

1. Discuss the many causes of the fragmentation of the health care system in the United States.

2. Explain the difficulty associated with the epidemic of chronic diseases and their complications.

3. How can the members of the public and their legislative representatives be made to appreciate the value of prevention in dealing with the health care crisis in the United States?

4. Why is this country failing in its efforts to reform the health care system?