Chapter 6

Leadership and Politics in Public Health

Learning Objectives

- Understand how power develops in organizations

- Become aware of the need for leadership skills in public health

- Recognize the role of leadership and politics in the changing health care environment

- Acknowledge the need for new roles and responsibilities for those who work in the field of public health

- Be able to explain the various styles of leadership and relate them to worker empowerment and innovation

The world of business, which includes health care services, is changing every day, catching many companies unprepared to deal with the new customer. The new customer wants quality in both the products and the services he or she purchases, and often does some research before buying anything. The world of business is in a revolution, changing very rapidly to better serve the customer. This is also true in the realm of health care services.

It is a proven fact that bureaucratic organizations do not work well in times of rapid change. A bureaucratic structure often exhibits redundant layers of management that prevent a business from responding rapidly to competition and the needs of its customers. They can only respond rapidly to consumer demands by talking to their customers and empowering their employees to rapidly respond to consumer needs. Health care is no exception to the rapidly changing consumer. Because of the changing nature of the health care system, health care managers relying on rules and regulations need to be replaced by strong leaders who can empower workers to deliver services that meet the needs of the consumers of health care—the patients. This will require a movement from a bureaucratic organizational structure and decentralization of decisions to lower-level employees. This change is also affecting public health departments as they attempt to do their job and retain their funding.

This is not to say that management does not have a role to play in the health care industry, including public health departments. We will always need to have elements of management and control in any business. Managers will assume responsibility for using nonhuman factors of production like technology and equipment in delivering health care services in order to provide for planning for future activities. In fact, managers do very well when they are responsible for things rather than people.

The health care industry is a part of the service sector of our economy, using human beings to provide extremely important services to other humans. This is where management principles do not work very well. Health care workers require leadership and empowerment to rapidly respond to the patient's ever-changing needs. Therefore, there needs to be a separation of the human and nonhuman components of the delivery of all health care services in order for things to be managed and people to be led.

Most leaders in health care delivery have the unique ability to separate the real problems from the symptoms that resonate from those real problems. They are usually very capable of developing and sharing a vision of what the future could be if we work together and concentrate on the real problems of health care delivery in this country. Leaders are also skilled in productively using their power to make change happen. In other words, they can define the real problems such that people understand why change is necessary in any serious effort to improve health care delivery.

Effective leadership is not about personal success. It is about uniting people in the business around a vision or common purpose. Leadership involves the ability of an individual to influence others to accomplish a predetermined goal. Further, Yukl (2010) argues that leadership involves having influence over individuals to guide or facilitate group activities. It is that special something that separates successful organizations from those that fail. It seems to be one of the most important components in determining the effectiveness of organizations. It is the glue that holds a thick, positive culture together, allowing the achievement of greater success.

Development of Power in Health Care Delivery

The use and abuse of power remain the major reasons for many of the failures in our current system of health care delivery. The power needs to shift to the consumers of health care and away from the providers of care. There are a number of people who believe that the majority of the income the various players in health care delivery receive is a direct result of health laws and regulations. Legislation determines who can and cannot practice medicine, dispense drugs, and admit and discharge patients from hospitals. The rules and regulations actually determine all income in health care. They are responsible for the development of power in health care, which in turn has shaped the way we deliver health care to our citizens. It will be virtually impossible to make positive change in health care without first dealing with the power of those who currently control this very large and vitally important sector of the American economy.

Power is nothing more than the ability to influence the way things are done or how goals are accomplished. There are several types of power, including legitimate power, coercive power, reward power, expert power, and referent power. Legitimate, coercive, and reward power originate from the position one holds in an organization. Expert and referent power are found in the individual and are considered personal power. Legitimate power comes from the top administrators of an organization and usually produces a bureaucratic organization run by a manager who follows the rules and regulations put forth by those top administrators. This is the way health care operates and the major reason why change is usually blocked. Those in power fear the loss of control if things are done differently. Personal power, however, is found in many individuals and is owned by each person, not the organization.

Figure 6.1 shows the sources of both position power and personal power. It is interesting to note that power is necessary to make change happen but that it can also block change from ever occurring. Both types of power take time to develop and are very important to getting anything done in any organization or relationship. You lose position power when you leave your position in an organization, whereas you take personal power with you. Leaders usually have personal power, but they may or may not have position power.

I (Bernard) experienced the abuse of power very early in my career. My first position in public health involved investigating venereal diseases, now called sexually transmitted diseases. My duties included interviewing those infected with syphilis and gonorrhea, and finding their sexual contacts and bringing these individuals to treatment. In this position I was not allowed to educate young people to prevent infections, but rather was required to spend all of my time finding infected people. In fact, it negatively affected my annual evaluations if I used my time educating children in school districts. When I questioned my supervisors about the value of prevention rather than control, I was told that I was not paid to educate.

This is a very good example of the power of program directors forcing a system not to change even though it is obvious that the wrong approach to solving a problem is being used. Many more types of sexually transmitted diseases have become epidemic among younger and younger children in this country over the years. The misuse of power is at the root of this failure, and even today the majority of money allocated for coping with sexually transmitted diseases goes to contact tracing and not education.

This is the same type of arrogant abuse of power that is keeping our health care system focused on treating expensive illnesses rather than on supporting wellness, which would lower costs, reduce access to health services, and diminish monopoly profits for those in control. Those in control resist change because they cannot envision a new health care system that preserves their power and wealth. They are probably right—if we had a health care system that kept people well, the large monopoly profits of many providers would disappear. This change-resistant mentality must shift if the greatest health care system is going to survive. Effective leadership has been difficult to find in health care because of the development of power in the various groups that control how the system functions. In order for leaders who want to change the system to emerge in health care, they must have the courage to face the tremendous power of those who control the resources of, and therefore rule, the health care industry. In order to begin to deal with the problems of health care delivery, the workers in health care must become empowered to offer quality and cost-effective services to their customers. Further, the leader must first be empowered before he or she can empower others.

The normal response by a business when a given strategy is not producing the desired results is to change the strategy. Systems of health care delivery do not seem to follow this business practice, even though health care outcomes are less successful than desired. There has always been a very strong resistance by those who are rewarded and have power, especially those who control payment and those who receive the payments, to changing the way health care is delivered in this country. This is because there is no incentive to change. In fact, it seems that all of the financing in the payment for health services helps to make problems in health care worse. It is probably the only industry that is paid more for failed services. The system attempts to do too much of the wrong things, including treatment measures that have very little if any value in their contribution to good health.

Even though everyone understands the need for wellness efforts in order to improve the health of our nation, the financial incentives still favor illness rather than wellness. This is because the American system of health care has been built around illness and does very little to encourage individuals to stay healthy. In fact, the only time when you get anything back from your health insurance is when you become ill and start receiving bills for treatment of your poor health that you can pass on to your insurance company. There is very little incentive for you to practice healthy behaviors that would help you remain free of disease as you grow older.

This paradigm of health care must be shifted. It makes absolutely no sense to allow individuals to become ill when it is well known that a large majority of illnesses could have been prevented if the delivery system were changed. This required change should also include modified incentives and reimbursement structures, and will most certainly affect the incomes and power of those who currently control the system.

The right change in our health care system could solve simultaneously the problems associated with cost escalation, uneven access to health care, and diminishing quality of life as we age. This change would require action rather than discussion about the value of wellness programs. It is possible to produce financial incentives that can slowly transform an illness-based health care system to one that incentivizes keeping people well. This change will not occur while all monetary incentives encourage treatment of illness and ignorance toward the value of preserving the population's health.

There is enough blame to go around for our failures in producing better health for our population. Everyone in health care, especially public health departments, have to get involved with the change process, empowering their followers to recognize and respond to the need for change in health care delivery. Extraordinary achievements require active support of others. This requires trust, and trust can only grow when the leader and the followers work together according to their common vision.

In a recent report titled The Future of the Public's Health in the 21st Century (Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2002, p. 4), a very prestigious group of health experts made the following recommendations to public health departments for improving population health:

1. Adopting a population health approach that considers the multiple determinants of health;

2. Strengthening the governmental public health infrastructure, which forms the backbone of the public health system;

3. Building a new generation of intersectoral partnerships that also draw on the perspectives and resources of diverse communities and actively engage them in health action;

4. Develop systems of accountability to assure the quality and availability of public health services;

5. Making evidence the foundation of decision making and the measure of success; and

6. Enhancing and facilitating communication within the public health system (e.g., among all levels of the governmental public health infrastructure and between public health professionals and community members).

In order for these recommendations to become reality, leaders must emerge from among those who work in public health in the United States.

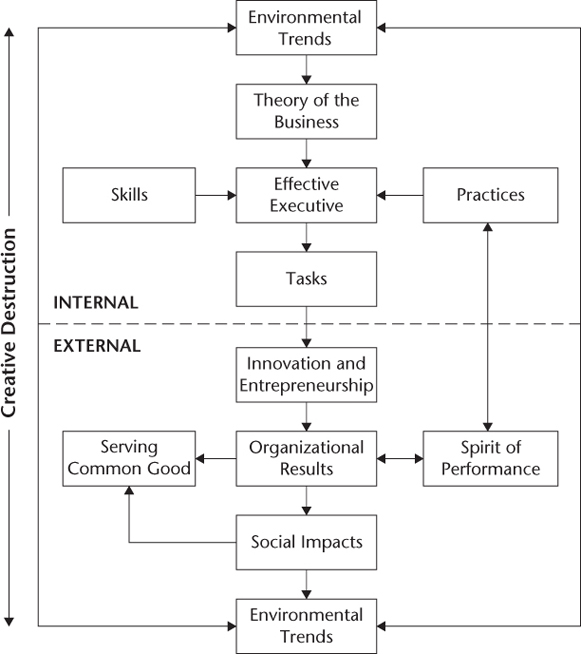

Maciariello (2006) offers a systems view of executive leadership and effectiveness put forth by Peter Drucker a number of years ago. Figure 6.2 provides a systems view of the internal and external components of leadership that are prerequisites for accomplishing the actions and changes the Institute of Medicine proposed in 2002. Drucker points out that this figure shows the three interconnected areas of leadership and effectiveness—personal attributes and practices, special skills, and particular tasks that a leader must perform in order to improve his or her effectiveness (cited in Maciariello, 2006). Individuals can develop these attributes through leadership training programs. We will discuss the skills public health administrators require in Chapter Nine.

Leadership and Politics in Health Care Delivery

There are many who believe that we have a crisis in our health care system in regard to the leadership of health care institutions—a crisis that involves the politicians who develop and ultimately fund policy decisions related to health care. The government is the largest payer of health care services and concentrates on paying for medical procedures rather than reimbursing for the outcomes associated with medical interventions in the overall health of the patient. The U.S. health care system is in desperate need of strong leadership in order to solve the problems that poor management and a lack of attention to the patient have caused. Other sectors of our economy, such as automobiles, computers, and software development, have been restructured in response to a crisis, and actually began to perform better after leaders came forth and made appropriate changes in the way they were managed. In its own state of crisis, the health care sector needs the wisdom of leaders who can diagnose the real problems and respond with the necessary solutions. These health care leaders must be able to bring together followers in a united vision of better health for all at a price that we can afford.

The health care sector has not seemed to require leadership in the past, primarily because of the way health facilities and physicians were reimbursed for care. The old retrospective reimbursement system actually rewarded inefficiency by paying for care regardless of its outcome. The result was tremendous waste of scarce resources, inappropriate tests and hospitalizations, and the expansion of poor managerial decisions. The health care industry became a hopeless bureaucracy that received rewards for poor choices. Many powerful coalitions such as medical and hospital associations still exist, hold tremendous power, and are blocking the needed change to a system that advocates preventive care as the model for delivering health services.

Bureaucratic management techniques have not worked very well in most organizations in recent years. Decisions need to be made rapidly and usually require an empowered workforce capable of immediately responding to consumer demands. Bureaucracies, which are organizations run according to rigid rules and regulations and directed under centralized authority, are not designed for rapid response to consumer needs because of the rules and regulations the management imposes. Leaders rather than managers have a much better chance of inducing a rapid response to shifting consumer demands, especially in the delivery of services. The health care delivery system is a business that provides very special services for its customers. It is no secret that these services have been poorly managed in the past, and the system is seeking leadership, just as are other sectors of our economy that are also facing troubled times and having difficulty responding to rapid change.

Never have the problems facing our health care system been so numerous and so very difficult to solve. These challenges can only be resolved by strong leadership. Although there are problems in health care delivery, there are also numerous opportunities present to actually improve health care outcomes as the health care sector reorganizes. The industry needs to carefully reevaluate how its practitioners deliver health care and to try to improve the entire process. This is clearly a time of profound change in the paradigm of how medicine works. There is no reason why they cannot shift the health care system's focus to prevention and away from waiting for people to become ill and then attempting to cure them. The old system may have worked well with communicable diseases, but it has failed utterly in regard to chronic diseases that cannot be cured.

It is interesting to note that the public health sector is also changing the way it seeks to improve the health of all Americans. Public health departments are focusing more attention on the need for leadership development in order to accomplish their goals, and are also attempting to increase their responsibilities and learn how to better evaluate the success of their own health interventions. Although the challenges are enormous, the opportunities to improve the health of all Americans have never been more abundant. In order to exploit these opportunities, public health departments must learn how to lead communities in the improvement of their health.

A landmark report concerning the state of public health, The Future of Public Health (IOM, 1988), demanded leadership development for those charged with delivering public health services in this country. The report argued that “the need for leaders is too great to leave their emergence to chance” (p. 6). The report went on to recommend that public health leaders develop greater leadership effectiveness, and that schools of public health add leadership to their curriculum. This report has influenced the increased provision of leadership education to individuals pursuing a career in public health.

The Institute of Medicine's report (1988) also called for the emergence of a special type of leader for public health departments in the new century. This new leader will perform traditional management functions, but will also work with stakeholders, community groups, and other government agencies in order to push public health goals to acceptance and achievement. This new leader will require special talents, including a firm understanding of public health problems to be overcome and the leadership skills needed to unite followers in the accomplishment of the new mission of public health. Assuming such a leadership role would be a challenging task for those placed in leadership positions in public health departments, but it could be accomplished if those in charge possess the appropriate leadership skills.

The public health leader needs to continue to build a thick departmental culture that empowers dedicated public health workers to become the key sources for motivating new tasks, and encourages them to accept changes as opportunities for growth. We must understand public health leadership to be a never-ending process. The vision has to include the protection of all Americans from the many dangers of their environments and from their own high-risk health behaviors. Strong, consistent, visible leadership is essential for sending a message of support to all Americans. Public health leaders must also work to bring together the medical establishment and public health departments in an attempt to improve health, and ultimately to reduce health costs and increase the quality of care.

Public Health Leadership Styles

Some of the older theories of leadership assert that leadership qualities are inherited. In other words, leaders have leadership traits built into the genes their parents gave them. According to Lussier and Achua (2004), leadership traits are distinctive characteristics (like physical appearance or self-reliance) that account for the effectiveness of a leader. From these theories there emerged the belief that several traits are responsible for one's ability to lead. Pierce and Newstrom (2006) define traits as general characteristics that could include individual motives, capacities, or patterns of behaviors. There are many who believe that these and other general traits may contribute to what makes someone a good leader. Traits do matter in leadership, but they are not enough to define a good leader. Because traits cannot be taught, it makes very little sense to include trait theory when considering the development of public health leaders. If an individual requires certain traits to be a leader, then the old adage “he or she is a born leader” would seem to be true. There is no question that being gifted in speech or exuding self-confidence does not hurt your leadership capabilities, but having these traits does not guarantee that you will become a leader.

Novick, Morrow, and Mays (2008) argue that having a certain trait, like being tall, does not in itself guarantee success as a leader. It is true, however, that certain traits help the leader communicate his or her vision to followers in a more believable format. If the followers agree with the vision, the voyage to successful goal attainment becomes much easier. These are communication skills, and it is likely they are learned rather than inherited.

There is no question that leaders are different from nonleaders, whether in regard to their traits, the situations they have to face, their exposure to leadership training programs, or a combination of all of these conditions. It is important for public health leaders to come in contact with all of the various leadership theories in order to understand the importance of leadership and learn how to grow as leaders to face the near-impossible tasks that will continue to confront public health departments in the future.

The way a leader behaves influences his or her followers. From the moment a new leader is introduced in an organization, the followers begin to watch and evaluate his or her behaviors. Northouse (2007) argues that leaders generally exhibit two kinds of behaviors: task behaviors and relationship behaviors. Task behaviors focus on the job, whereas relationship behaviors concentrate on interpersonal abilities. Both kinds of behaviors work very well in some situations but fail in others. There seems to be solid agreement among most researchers that the situation is the controlling variable that determines which leadership style works best. Leaders of public health programs may require a combination of these behaviors to accomplish public health goals. Therefore, possessing people skills may not be enough to be a successful leader of a public health department, especially in the twenty-first century. In order to attract more resources from tight government budgets, public health departments must continue to solve public health problems. This may require the leader to revert to task behaviors when goals are not being accomplished.

A leader's style—the way he or she behaves—is of great importance when he or she interacts with those purchasing a service from his or her organization. Public health is a service industry that for the most part shares information with individuals regarding their health. This type of business usually requires an administrator with a people-oriented leadership style. Public health departments have a small staff and limited resources available to accomplish very large goals. They are forced to rely on community support to achieve these goals, and in order to gain such support their leaders need strong people skills—including the ability to communicate with community stakeholders.

There are times when a leader must exhibit task behaviors in order to be successful at a given mission. The public health team is responsible for accomplishing the goals, whereas the leader is responsible for giving the team the resources they require in this process. Quite often a leader's task behaviors may facilitate the goal accomplishment. Relationship behaviors come into play when a leader helps team members feel good about and supported in whatever they are trying to achieve. It seems obvious that in order to lead public health departments in this new century, leaders require both people- and task-based skills…yet many current administrators in these departments are devoid of either type.

In order to better understand leadership, it is helpful to understand the motives an individual might have for seeking and accepting a leadership role. Manning and Curtis (2007) argue that there are three motives to lead—the desire for achievement, the desire for power or the ability to influence others, and the desire for affiliation interpreted as an interest in helping others. There is no question that the majority of people who seek a career in public health do so because of a desire to help other people. The problem is that most top positions in public health departments are given to political appointees, who usually have a short tenure. These appointees have usually helped the governor or county administrator win the election, and are then rewarded with a position in a government agency. Many of these political appointees have a motive to survive and keep their job rather than to take the risky road of leadership. If a potential improvement poses a risk to the political appointee, you can be certain that the improvement will not occur. This is why public health departments are so very conservative in their approach to change.

According to Kouzes and Posner (1995), every leader seeks challenge, exploits change, and understands the great risk that is present in all of his or her actions. By definition, managers are not expected to go beyond the planned outcome that has been determined by their superior. Leaders, however, allow the larger vision and not the planned outcome to determine the results of their activities. It is very difficult to push for a vision that is controversial and may cost you to lose power and even your employment. This is why public health administrators have been reluctant to criticize our current health care system—being critical of this system is risky because those responsible are afraid to take on the medical elite for fear of losing their political appointment.

The style of the leader is contingent on the way he or she behaves. This style is especially visible in the leader's interaction with the employees of the organization or group of which he or she is in charge. It seems obvious that the way a leader behaves affects employees' response to him or her as well as their performance. Lussier and Achua (2004) argue that several studies of leadership theory conducted over the last thirty years have continued to focus on two major types of leader behaviors: task- or work-centered behaviors and employee-centered behaviors. Again, the type of behavior that works best for the leader depends on the situation he or she faces.

The motivation of both the leader and the followers is also important in determining followers' behavior and their response to that leader. A bureaucratic leader who is afraid of risk will not be able to achieve public health goals in the twenty-first century. It won't take long for bureaucratic leader behaviors to destroy the thick culture of public health workers, and once this culture is ruined it will take years to repair the damage.

Leadership is a small component of the entire process of public health management, but also one of the most important—especially to organizations that supply services. Novick et al. (2008) point out that those responsible for the management of public health programs may not offer leadership to practitioners because of their own lack of training or experience. This must be changed in order for those in charge of public health departments to understand the value of leadership.

Transformational Leadership and Public Health

There are many styles of leadership, but the gold standard in service organizations seems to be the transformational style of leadership. According to Trompenaars and Voerman (2010), transformational leadership involves the leader's ability to change the consciousness of his or her followers through identification of desires that were previously unconscious. This type of leader represents the ultimate change agent.

This is certainly the case when dealing with a volatile environment that is ripe for change and in need of innovation in the delivery of services. The health care industry has been attempting to change the way it delivers care for the last twenty years. The new health reform law passed in 2010 has become a catalyst for improving the health of the population by including a number of provisions that focus on disease prevention. Because of this new law, public health departments have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to be catalysts for reforming the way health services are delivered in our country. Exploiting this opportunity will require strong leadership that supports empowered workers.

Northouse (2007) points out that the transformational style of leadership does not include assumptions about how a leader should act; rather, this style encompasses a way to think about leading. This style's emphasis is clearly on inspiration and innovation in the way the organization does business. The transformational leader works to inspire followers to look for change on a daily basis and exploit that change to improve the business. The transformational leader is very interested in both developing a vision and achieving this vision through his or her followers. This leader wants not only to achieve personal and organizational goals but also to see his or her followers achieve their personal goals and grow in the process. In order to accomplish this, the leader has to share power.

Tichy (1997) argues that the transformational leader seeks to transform his or her follower into leaders themselves. This implies that the major role of a transformational leader is to positively motivate those around him or her, directing followers' energy toward goal accomplishment. This synergy allows the impossible not only to become possible but also to become the norm for the organization. This is exactly the leadership style that is needed to provide direction through the ambiguity confronting public health departments in the United States today. These departments need to better define how they plan to accomplish their long-term goals in accordance with Healthy People 2020. The U.S. public health system is faced with increasing demands, limited or declining budgets, and politicians who want no part of public health until there is an emergency. Then the politicians throw money at the emergency and try to make it go away, when it could have been prevented in the first place.

Novick et al. (2008) believe that transformational leadership in public health requires true empowerment of all team members to accomplish predetermined goals for their program. Such empowerment may create serious problems for the department head due to the political nature of public health departments. These problems might include offending individuals or groups of people who disagree with a particular public health program, such as one that dispenses condoms to younger children. This is one of the reasons for the short tenure of many leaders in public health departments: doing the right thing for the health of the people entails risk to employment, even from the very people leaders are attempting to help.

Northouse (2007) points out that a transformational leader has the unique ability to get all team members interested more in the current project or organizational goal to be achieved than in their own personal interests. This type of leader should be communicating the goals of public health to all of the various constituencies, including community leaders, that have the resources and support to make these aspirations achievable. People are attracted to the transformational leader because he or she is able to explain his or her cause in such a way that supporters understand and want to be part of the movement toward better health for all.

According to Beltsch, Brooks, Menachemi, and Libbey (2007), public health departments have to manage old programs that have never finished accomplishing their goals as well as new programs that add to their responsibilities—all with a dwindling resource base. Public health has never been funded very well in this country because it has never been truly understood by those who control funding. There are many reasons why public health is not fully understood, but the answer to this dilemma may very well be found in the dearth of leadership skills among the top executives of public health agencies. Beltsch and colleagues argue for a change in this country's investment in public health activities. This investment has to command accountability for resource use and the development of a well-trained cadre of public health program leaders. These goals are large, but they can be accomplished through the development of public health leadership and through partnerships with other community health agencies, businesses, and school districts.

According to Novick et al. (2008), one of the major problems the transformational leader faces is the tendency for followers to change back to their old ways of doing things if the leader is not always present. Once the transformational leader is not available to support followers, the old ways of delivering services tend to reemerge and become dominant. Followers are often dependent on the charisma that is always present with the transformational leader. This makes the short tenure of a public health leader a very real liability in the transformation of a public health department. The followers who are left when the transformational public health leader departs are unable to function with the same energy because they feel that part of their team is no longer available. In these instances, the former leader usually has not had the time to fully develop his or her replacement. Further, because most public health departments are funded by government and, therefore, political, there is no guarantee that another leader with transformational leadership skills will be appointed.

Public Health as a Change Agent

A profound change in operations is needed to save the U.S. health care system. Kotter (1995) argues that managers are usually engrossed with complexity, whereas leaders devote their time to change. The pace of change has quickened in recent years, and nowhere is the change process happening at a faster pace than in the service sector of our economy. Public health departments offer services, and they too are caught up in the accelerated process of change. Public health leaders must be capable of responding to change in the form of new crises and new responsibilities that present themselves on a daily basis.

Strong leadership is never in greater demand than when there are dramatic shifts in the way business is done. Pierce and Newstrom (2006) discuss how leaders require the ability to frame reality for their followers. This framing or structuring of the future must be done in a meaningful way for members of the organization to accept and work to achieve the goals associated with that future. Leaders today must learn to manage change rather than simply react to it (Lussier and Achua, 2004). In fact, leaders must be able to exploit change for the opportunities that it can open up for their organization. Change can also bring threats of which the organization needs to be aware, and to which the organization must develop a proactive response in order to continue growth. Finally, those in leadership positions in public health have frequently seen change as the enemy because they fear loss of position power.

The leader and followers need to develop a concept of change as more of a process than a product (Lussier and Achua, 2004). This entails acceptance by the entire organization that environmental change is the catalyst that will transform the organization to meet the vision espoused by the leader and accepted by his or her followers. Change can then become a continuous process of quality improvement and growth for the public health agency. Stadler (2007) points out that one of the prerequisites for leading on a long-term basis is to be conservative about change. This author advocates the exploitation of change, but does not advocate for radical change without appropriate planning. In other words, the leader needs to prepare the organization for opportunities that present themselves through change, but he or she must do so with caution. This is very good advice for public health departments that are always in the media spotlight when public health problems develop.

Public Health Leaders and Power

An individual requires a power base in order to lead any group or organization. Northouse (2007) argues that in order for a leader to influence individuals, a power relationship must exist between the leader and the followers. Because goal achievement requires change, the use of some form of power is required to make change happen.

Northouse (2007) also points out that there are usually two major types of power found in individuals, which are derived from the position or are found in the individual. They are position power and personal power. Lussier and Achua (2004) argue that perceived power may be the key ingredient in developing the ability to influence others. In other words, to influence others, leaders may only need followers to think that they have either position or personal power. These are interesting concepts to keep in mind when evaluating public health leaders' ability to influence followers toward the achievement of public health goals.

Because the vast majority of public health agencies are government sponsored, their structure is usually bureaucratic. A bureaucratic organization relies heavily on position power to achieve its goals. This type of power is derived from the top management or the chief executive of the government entity and flows from the top of the organization downward. Position power involves legitimate, coercive, and reward power, which are owned by the organization and not the leader (Lussier and Achua, 2004). This type of power can be taken away from the individual if he or she makes mistakes. Therefore, bureaucratic leaders are always at risk of losing their position power if they anger those above them in the organizational chart. This makes these leaders very cautious about making decisions, especially if they involve risk.

Risk is part of making change happen, and if the bureaucratic leader's career is in jeopardy every time change is required, he or she will be less inclined to take part in the change process. This has always been a recognized impediment to making rapid change happen in government. Public health leaders are well aware of the implied risk in any actions they undertake to deal with public health issues. There is always the chance that being part of change that affects large numbers of people may anger some politically powerful individuals. The end result of this type of confrontation can be a public health leader's having to relinquish position power.

Lussier and Achua (2004) also discuss the personal power that some leaders possess. Personal power comes forth from the leader and is owned by the leader. When an individual leaves an organization, he or she takes along personal power. Personal power confers on a leader the ability to influence individuals because they like him or her and respect his or her expertise (Northouse, 2007). The two types of personal power usually found in leadership research are charisma and expertise. Charisma, or referent power, consists of certain traits found in an individual that are appealing to followers (Lussier and Achua). This type of power results from relationships with others and usually involves friendship or loyalty between the leader and the follower. This type of power can be developed through education and training programs. It is interesting to note that personal power can also be found among followers who are not in any type of leadership position.

The transformational style of leadership relies more on the personal power of the leader than it does on position power, and the transformational process requires the leader to be considered a competent role model by his or her followers. Such a leader has a vision of the future, and everything that leader does is part of the road map to the attainment of that vision. Getting followers to espouse the vision through the use of personal power is one way to speed up progress in making the vision a reality. Healthy People 2010 is a vision for population health that requires transformational leadership to achieve all of its objectives. Novick et al. (2008) argue that in order to accomplish large goals that have an impact on the American public—like those put forth in Healthy People 2010—public health leaders must collaborate with others in the political landscape. This is where the transformational style of leadership can serve the public health leader. By collaborating with others on the achievement of community goals, the leader can avoid the political dangers of trying to accomplish broad public health goals.

Public Health Leaders and Conflict Management

In order to attain the goals of public health in the twenty-first century, public health leaders will have to experience and learn how to manage conflict. Bureaucratic organizations usually see conflict as bad and attempt to suppress conflict with a heavy reliance on rules and regulations that prevent it from arising. In the new world of public health, we should view conflict as normal and even energizing, and top management should actually support it. Manning and Curtis (2007) argue that conflicting goals and personalities are expected among people in a healthy, vibrant organization. The leader needs to be aware that change is the breeding ground for conflict and that part of the leader's role as change agent is dealing with this conflict. The leader must also be aware that while he or she is attempting to improve the health of the community there will be conflict among some segments of the community population.

Leaders need to realize that the success of a public health agency may depend on how well it handles conflict. Lussier and Achua (2004) argue that conflict management may take up to 20 percent of leaders' time and a great deal of their energy. The ability to handle that conflict may be one of the public health leader's most important skills; the leader cannot and should not try to avoid conflict. Conflict resolution can build collaboration throughout the organization and sometimes the community—and collaboration is needed to make public health departments stronger and able to achieve greater goals as they address twenty-first-century health problems (Lussier and Achua).

Can Political Appointees Lead Public Health Departments?

The predominant form of public health department in the United States is a local health department (LHD). The LHD is most often the responsibility of the city or county government, and its powers and duties are granted by the state. There are approximately three thousand LHDs functioning in the United States, all of which provide mandated public health services and many of which are responsible for the development of new and innovative public health programs.

The major power (control of resources) is usually found at the state level. The leadership positions in public health at the state level are almost always politically appointed by the governor or his or her designee. The IOM (2002) reports that a state public health official's term in office is tied to the governor's term, making the average tenure for these appointments 3.9 years, with a median of 2.9 years. This is certainly too short of a time frame for an appointee to use any leadership skills that he or she may have, given the learning curve necessary to fully understand the role of public health in the community. Tenure, or time in the job, is a critical component in the development of leadership skills. The politics of public health leadership needs to be studied at length if we are ever going to be able to develop strong public health leaders and empowered followers as we work to keep our nation healthy, free of disease, and protected from the many threats to the public's health.

Public health leaders need to learn how to develop their staff and share the power of the agency with all of the workers involved in serving the public, even though this is very difficult to accomplish within a short tenure. The public health system in this country is most dependent on its greatest resource—its workforce. These dedicated individuals come from a wide range of professions, educational backgrounds, and motivations for pursuing a career in public health. These are individuals whom the public health leader needs to energize toward accomplishment of public health goals. It is these people who can develop and implement the prevention programs to deal with the epidemic of chronic diseases.

These followers, because of their diverse training experiences and their thick professional culture, cannot be managed for very long in a bureaucratic organization. They are different—because of the nature of their duties—in that they need to be empowered both for personal growth and for the accomplishment of organizational goals. It takes political appointees in management positions in public health agencies a long time to understand how very different these followers are. They cannot be managed; they must be led and truly empowered or they lose their motivation to perform—at which point they get frustrated and move on to the private sector, where their skills are better appreciated.

According to Pierce and Newstrom (2006) it is very important to understand the role of the follower if one is ever to understand the process of leadership. In other words, we must understand the traits that make up the followers if we are to gauge their receptivity to certain leadership styles. If the leader is ever going to be successful at gaining the support of followers, he or she must pay a great deal of attention to followers' needs, perceptions, and expectations. The vast majority of followers in public health have longer tenure in their positions than the leader. They also have been through changes in management in the past. They are conditioned by what happened and did not happen with the previous leaders.

Empowerment then becomes a process in which the leader shares power with followers so as to develop their own personal power. Position power is absent from this definition of empowerment by choice. One never really owns position power, because the risk of losing this type of power is always present. Every time position power is used to influence or lead, there is always the risk of loss associated with that action. The tendency for individuals with only position power is to not take chances for fear of losing power and damaging their career. To those who only have position power, change becomes the enemy and is, therefore, resisted. Leaders who fear change tend to avoid empowering their followers because this empowerment increases the leaders' chance of losing position power. Public health departments have been the victim of many administrators who did not seek to empower their followers. Fortunately for the American public, some leaders with personal power and the ability to empower followers also have been part of the history of public health. Even with short tenure they have been able to produce admirable public health accomplishments. It is unfortunate that this is such a rare occurrence in public health leadership, however, it being very difficult to respond to public health challenges when you are in constant fear of losing your appointment because of angering politically powerful groups.

Communication Skills of the Leader

Novick et al. (2008) argue that the most important skills required of a leader in the twenty-first century are communication skills. A leader needs communication skills to present the mission statement and goals of the organization, which is essential in getting all stakeholders to become supportive of the leader's vision (Lussier and Achua, 2004).

Northouse (2007) discusses the concept of emergent leadership in which followers believe that the leader has gained influence over the group through his or her communication skills. By being able to communicate with employees the leader can gain the trust and support of the individuals that are so important in the achievement of short-term and long-term goals of public health departments. Communication is actually a major part of the leadership strategy (Lussier and Achua, 2004). There is a very strong relationship between communication skills and the effective performance of a leader. Communication tools are essential to leadership development and goal attainment in public health. The IOM (2002) argues that leaders in public health must be able to communicate internally and externally in order to distribute vital health information to their staff, other agencies, the media, and the community. They must also be able to gather information from the public about disease occurrence and rapidly distribute to the public information concerning emerging public health problems.

Communication skills along with an understanding of the value of technology for health promotion can become very effective tools in responding to the epidemic of chronic diseases in this country (IOM, 2002). The IOM recommends that all partners within the public health system make communication skills a critical core competency of public health departments. The IOM further advocates for the expansion of vital information systems that can help leaders rapidly disseminate public health information to those who need to know. The public health leader must understand and embrace the value of communication skills in the world of public health in the twenty-first century.

Leadership Development in Public Health

Mays, Miller, and Halverson (2000) argue that the demand for professional development, especially leadership training, has grown in response to a multitude of external forces. One of these forces is the need for collaboration among many community agencies trying to make their constituents healthier while also dealing with emerging infections and the threat of bioterrorism. The IOM recognized the need for leadership training in the executive summary of their 2002 report, in which they recommend that Congress increase funding for public health training, especially leadership training, for state and local health department directors. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also has responded with programs like the Public Health Leadership Institute and the National Public Health Leadership Development Network, which offer leadership development and training to public health professionals throughout the country.

As noted earlier, leadership skills are usually not part of the curriculum in schools of public health. “Getting an MPH [master's degree in public health] does not necessarily confer on you the realities of practicing public health, just as medical schools do not necessarily train doctors to handle money or management issues,” said Stephanie Coursey Bailey, chief at the CDC's Office of Public Health Practice (quoted in Gale Reference Team, 2007, p. 25). The IOM (2002) points out that the MPH is the degree that many public health workers earn, especially those who remain in public health long enough to become program managers. However, a large number of individuals found in leadership positions in public health have academic preparation in areas other than public health and usually have not received any leadership training. This is because they are political appointees, especially at the state level. Despite the academic certification of the public health leader, it is very rare to find individuals with strong leadership training credentials. This means that the individuals appointed to these positions may require training in public health along with leadership training in a very short period of time.

A very small part of the current workforce in public health departments receive training in public health before they begin their career. The average public health worker usually receives on-the-job training in a specific area of public health, such as epidemiology, public health nursing, laboratory science, or health education. Further, even if a worker has a degree or certification in the specific discipline of public health in which he or she is employed, there is almost no chance that the worker received training in leadership or communication skills as part of his or her formal education.

The Nation's Health offered an excellent article titled “Leadership Institutes Help Public Health Workers Advance Careers” (Gale Reference Team, 2007). This article highlights the value of public health workers' attending one of the many public health institutes that offer professional development opportunities to public health practitioners across the United States.

Geoffrey Downie, program manager of the Mid-American Regional Public Health Institute, said that all institutes “share the belief that system thinking is a key component to effective leadership and that community health will improve if the public health infrastructure is sustained and supported” (quoted in Gale Reference Team, 2007, p. 25). Joyce R. Gaufin, executive director of the Great Basin Public Health Leadership Institute in Salt Lake City, commenting about those who complete leadership training, said, “One of the most important individual benefits of participation is an increased sense of confidence about their own abilities and the actions they take as a leader” (quoted in Gale Reference Team, p. 25) These leadership training programs usually entail a one-year commitment, and the training is provided by expert faculty from leading schools of public health, business programs, and the private sector. Funding for these programs comes from a variety of sources, including the CDC, state and local public health agencies, and public health foundations.

We must continue and expand these efforts at providing leadership training opportunities to the public health workforce if we are serious about improving the health of our nation. “The need for leadership in public health is well documented, and many would agree that at no time in the nation's history has the need been greater,” said Kate Wright, director of the National Public Health Leadership Development Network. There is a great deal of discussion about standardization by the various organizations that are providing leadership training programs to members of the public health workforce, suggesting the need for schools of public health to develop best practices in public health leadership and to share them with leaders and followers in all public health departments throughout the country.

Culture of Public Health Workers

A culture is a combination of learned beliefs, values, rules, and symbols that are common to a group of people. Kotter and Heskett (1992) argue that developing a strong culture can have powerful consequences, because this culture can enable a group to become proactive in the way its members deal with the problems that confront them. In public health, the creation of a strong culture also results in most managers sharing a set of relatively consistent values and methods of completing work (Kotter and Heskett).

Hickman (1998) argues that a company with a corporate culture that pushes positive change understands the value of the individuals and the processes that create change. Such a company truly believes in its workers and respects its customers, and it shows every day in the way top management acts in the workplace. This company demonstrates a performance-enhancing culture that takes pride in its workers and customers and would never do anything to intentionally hurt either group.

The culture of an organization forms through a process of successful interaction that causes it to be assimilated throughout the workplace (Keyton, 2005). This interaction is a learning and teaching experience for workers in regard to how the process of work is accomplished. The leader needs to obtain from the workers a commitment to a shared set of values. This attempt at culture formation will only work if all workplace members are part of the process. Participation must be voluntary, and it must be a result of the workers' buying into the leader's vision. It is a continuous process that will never end because there will always be room for improvement in the work process.

The successful leader must work very hard at empowering workers to sustain a thick culture, spending a great deal of time and energy encouraging employees to embrace the goals of the organization and to actively work with him or her to accomplish the organization's stated goals. Empowerment is the complete sharing of power with lower-level employees who are critical to successful goal attainment. The leader is most effective when he or she has the ability to make a task for a follower meaningful. This task of building a culture of continuous quality improvement in the workplace is probably the most important responsibility of a leader in today's work environment. We will further discuss the culture of public health workers in the next chapter.

Expertise concerning the work process is a form of power that is usually already present among the workers and just needs to be activated by the leader. There are several ways that the workplace leader can empower the employees. The leader needs to consistently search for people who want to win and who can be empowered to translate short-term wins into long-term successes. Leaders have to create a culture in an organization in which workers are really the key sources for motivating new tasks, and in which employees accept changes as opportunities for growth. Smircich and Morgan (2006) argue that leadership situations consist of an obligation and right of the leader to structure the real world, which includes the leader's vision for others. In other words, the leader has the ability to control the behavior of followers to allow them to see and believe in his or her vision. The leader must recognize that followers need to agree to the vision he or she proposes and the work process that flows from this vision. Leaders should not make changes in the way work is done unless they rethink the process of work through discussions with those who actually do the work. This process should produce a culture that becomes adaptive to continuous change in the improvement of the process of work.

There are so many descriptions and definitions of leadership that it becomes virtually impossible to discover one definition that is accepted by everyone. As we have seen in previous sections, leadership is quite often described in terms of some type of power relationship between the leader and followers. The concepts of power development and power sharing can provide us with a better understanding of what the leader can and cannot do for the organization. The leader's potential for success diminishes if the followers in the workplace do not validate his or her power.

Leadership involves the ability to acquire the respect and support from members of an organization that are necessary to accomplish organizational goals (Dubrin, 2007). Leaders are responsible for developing the culture of the company to emphasize accountability and help managers understand that they are responsible for processes rather than activities. In order to do this, a bond must develop between the organization's leaders and employees. Leadership involves the sharing of power with every worker in the company in order for the business to succeed at accomplishing its major goals.

The leader who is gifted with charisma can communicate a vision of a workplace in such a way that workers are inspired to accomplish the goals inherent in that vision (Dubrin, 2007). The vision the leader articulates is capable of attracting others to want to be a part of it; it brings together workers who want to contribute to its successful realization.

Manning and Curtis (2007) point out that clarity of purpose can serve as a guide for a leader in making decisions that inspire others to follow the vision he or she puts forth. This clarity of purpose allows everyone the opportunity to understand the reasons for the decisions the business is making. Northouse (2007) argues that a transformational style of leadership is a necessity in getting workers motivated and involved in supporting the betterment of the company and the entire workforce, rather than only looking out for their own interests. The transformational leader works very hard to develop a supportive environment for listening to workers in an attempt to get them to self-actualize and become the best at what they do at work. This leader has a very clear vision of where he or she wants the organization to be in the future. Further, the vision the leader creates gives followers a sense of identity within the organization (Northouse, 2007). The followers are then capable of working together to ensure the successful realization of the vision. Strong team leadership most often manifests itself in the positive results the team achieves. Such positive outcomes are obtained as a result of the leader's constantly helping team members to keep their focus on goal achievement.

Individuals often become leaders in an organization after having the opportunity to be mentored by existing leaders. These mentoring relationships have been difficult to foster in health care facilities and more dangerous to develop in public health departments because of resistance to change. Such resistance often results from the fear of losing funding from the federal government because the program change is not included in the grant guidelines. This is another example of the problems with bureaucratic organizations. There is tremendous risk present when one attempts to deviate from the norm established by the bureaucracy holding the power in the health care system that includes public health departments. In an appointed leadership position in public health, your tenure can become extremely short if you try to be innovative in delivering health services. The reason for this tenure issue is found in the fact that politicians fear change and resist it to avoid alienating those who contribute to political campaigns. These politicians think that this risk is not worth the possible improvement in the public's health that might come from fostering innovative programs. Such resistance to change usually results in innovative public health leaders' leaving the public sector and taking their leadership skills to private agencies where they are appreciated. This results in there being very few leaders in public health who are willing to take a chance with innovation. It is simply not worth the risk.

Solving the many problems facing health care in the new century requires a shift from “I” to “we.” This allows the leader to become humble, causing him or her to refocus on the development of others. It is the health care worker and not the leader who delivers health care services to the patient. The leader realizes that and attempts to empower the worker to improve the services delivered to that customer.

Incentives can be the catalyst to action when it comes to developing the necessary leadership to keep people healthy at a cost we can all afford. The problems in our health care system require the emergence of leaders in the medical care sector and in public health departments throughout our country. These leaders need to be able to recognize the value of partnerships in the attainment of better health for all Americans. For this to happen, there must be education programs offered that are capable of developing leadership in those responsible for both public health and medical care. There also should be an understanding by leaders of the value of the medical care system and public health departments working together.

The current incentives present in our medical care system and public health agencies encourage the development of power and the use of that power for personal gain. The medical care system uses the pursuit of quality as the excuse for completing wasteful tests in order to improve profits for both the system and those who complete the work. The same system does very little to encourage individuals to seek preventive care. This is where there is a need for public health leaders to assume the leadership role.

Public Health Leaders and Innovation

The skills that could come forth from public health departments have never been in greater demand than they are today because of the evolving epidemic of chronic diseases. As we have already discussed, however, public health departments are suffering from the legacy concept, looking to old successes to solve current problems. We need strong leaders with developed skills to face the major challenges presented by the chronic disease epidemic. This will require transformational leaders at the top of public health agencies who recognize the value of the true empowerment of all public health workers. Public health leaders are unequipped to deal with the challenges of chronic diseases without the complete support and creativity of all of their followers and the community.

One thing that most transformational leaders have in common is their propensity for taking risks through the development of innovative approaches to the challenges confronting them. Rather than attempting to use the same strategies that worked in the past with different challenges, these leaders will usually look to changing the way things are done in response to new problems. A transformational leader will also look outside of his or her discipline to find ways of dealing with new problems. This has never happened with public health departments because they believe that all of the solutions to contemporary health problems can be found within their own discipline and in their own past successes. It is time to broaden the search for solutions to other disciplines and, in the process, spark creativity and innovative approaches to health problems. In order to achieve success with new challenges, public health departments need to engage their employees and their community.

Christensen, Grossman, and Hwang (2009) argue that new ideas do not usually emerge from a specified discipline, but are spawned from other fields using their expertise to examine problems of another discipline. This interdisciplinary approach is being applied to solve the various problems in our current medical care system. It is now time for public health departments to incorporate this approach. Public health departments can only benefit from intense scrutiny by those from other disciplines who look at the way they attempt to solve problems—and from their own explorations of other disciplines. These other disciplines can then share their expertise, offering a different set of eyes for the sake of problem solution.

This is where the development of public health leaders is such a vital component of the solution to the health care crisis facing our country. There is clearly a need for public health departments to move past their previous successes and on to new and greater achievements, which in turn demands leaders who will motivate followers to higher levels of job satisfaction and commitment. The ability to inspire others to accomplish greater achievements is probably a leader's most important competency. It seems to be the one component of leadership that is absolutely necessary in order to motivate large groups to achieve virtually impossible tasks time and time again. Inspiration is the catalyst that helps to further develop the thick culture public health departments need in order to accomplish even greater successes in this century.

Zenger, Folkman, and Edinger (2009) found in their studies of leaders that there is a very strong link between inspiration and innovation. Followers are attracted to a leader who inspires them to become part of new and exciting possibilities. Followers enjoy working for leaders who bring excitement to the workplace with new and exciting ways for approaching problems. Public health departments also need inspiration and innovation in order to become the catalyst our health care system needs in order to do a better job at keeping people healthy at a reasonable cost.

Zenger et al. (2009) argue further that effective leaders are capable of instilling confidence in their followers. In fact, most research indicates that successful leaders spend a great deal of their time working very hard to instill the confidence employees need to take chances and assume risk. These confident followers challenge themselves to attempt new approaches at work because the leader has given them the signal that it is all right to fail as long as they try. They are very aware that the leader wants them to succeed and believes in their ability, which further boosts their confidence.

Public health employees need to develop this confidence in their ability to prevent disease. These individuals have suffered through years of neglect, reduced resources, and a feeling that they are not appreciated. This lack of confidence in their ability and lack of inspiration from their leaders have resulted in a loss of self-efficacy. I (Bernard) experienced low self-efficacy during my tenure as a public health employee. I met very few leaders during my twenty-five years in government employment, but I managed to develop leadership skills through formal education and perusal of research concerning leadership. I was able to practice these leadership skills when I was assigned supervisory authority over a public health office, at which point I became a leader by default. I grew as a leader by ignoring the appointed leader, and gained the respect of my followers by allowing them to work independently. As my self-confidence grew, my self-efficacy grew. The productivity of my office increased dramatically. When self-efficacy is low in public health departments they lose productivity, causing those who allocate health resources to question the need for continuation of several public health programs.

Brown (1997) argues that leadership in public health is a prerequisite for public health departments becoming more effective in achieving their goals and practicing innovation in the delivery of new public health programs. This is going to require collaboration with other agencies, especially businesses. In order to make partnerships work, however, there is a real need for exceptional leaders. These other agencies have experience, expertise, and of course resources that public health departments need if they are ever to resolve the tremendous health challenges facing this country in the next several years. Public health leaders must learn how to inspire these agencies to work together to achieve success.

Strong leadership skills are just starting to be appreciated as an absolute requirement for those who are charged with leading public health departments into the future. The challenges we face in this century—such as the epidemic of chronic diseases—are growing by the day, and they are incapable of being managed, requiring instead leaders with a vision for how to solve these public health problems.

According to Gallo (2011), for innovators to be successful they must follow their heart, as Steve Jobs has illustrated throughout his string of innovations for Apple over the last thirty years. Such passion should also drive those who truly believe in the enormous potential of public health departments. The secret to success for most leaders who are trying to make change happen seems to revolve around their passion not only to dream but also to spend the vast majority of their waking hours making their dream come true.

In order to truly become a change agent you have to follow your dream, that which is your passion—then you can work long hours, experience failures, and still follow the vision because you own it. The secret of successful innovation then becomes perseverance in striving toward the accomplishment of your dream.

People who work in public health usually love what they do or they would have abandoned the field many years ago. The compensation is low, promotions are rare, and frustration in meeting goals because of meager resources is a daily occurrence. Those who choose the field of public health as a career do so because they are passionate about trying to improve the health of the population. The problem is not the passion of public health workers; but quite often it is the dearth of credibility among leaders found in public health departments. This lack of credibility is not always a result of bad leadership, however, but rather stems from the short tenure that comes with being a political appointee with very little understanding of the goals of public health departments.

Credibility—that is, the leader and his or her vision are believable—remains one of the most important qualities of the leader, reinforced over years of research. A culture of credibility emerges when everyone in the organization is held accountable for high performance. This instills trust between the leader and all of the members of the public health team. These employees are then more likely to support risk taking and to become extremely interested in finding innovative ways to better serve their customers.

Gallo (2011) argues that the combination of passion and aptitude can truly change the world. Public health departments require such a combination among their workers to begin meeting today's health challenges, especially the current epidemic of chronic diseases and their complications. The development of Healthy People 2020 goals is fine, but meeting those goals requires unleashing the passion found in the vast majority of individuals who work in public health departments. These dedicated people need to experience empowerment in the workplace in order to devote their creativity toward innovation in finding solutions to complex population health problems.

According to Kouzes and Posner (2009), a culture of leadership is present when every person in the organization is thought to be credible and accountable to each other. In this type of working environment, risk taking is not only accepted but encouraged. Public health departments need this leadership environment if they are ever to repeat and expand on their past success stories. The problem lies in that bureaucratic government agencies do not support risk taking because of political dangers associated with risk. You cannot fully commit to something that is not important to you. This has been the major problem with public health departments—they are committed to population health but not to combating the inactivity associated with a bureaucracy. These dedicated employees want to make a difference in people's lives.

Gallo (2011) argues that real innovation is not the result of focus groups or expensive marketing research. It comes from knowing your customer and showing them products and services that will make their lives better. This is also true with programs that try to improve the health of the population. Americans do not know how much they want good health until they experience poor health, and then it may be too late to restore their health. Americans also do not realize the value of prevention begun at an early age.

A very good example of a company that makes things simple for the consumer is Apple computers. This company is exceptionally skilled at making very difficult tasks very simple. This is because the vision of the leader is capable of unleashing creativity and innovation in solving problems. This is the type of innovation public health departments require in order to deal with the epidemic of chronic diseases. Public health departments need to look at successful companies like Apple and make the process of delivering health education more successful through the use of disruptive innovation. They need to use innovative technology to deliver health education and health promotion activities to the entire population.

Leadership has replaced management as the component necessary to accomplish goals in most organizations in the United States. This is also very true for public health agencies as they respond to the many challenges to and opportunities for improving the health of the population as our health care system reorganizes.

The Institute of Medicine in 2002 called for tremendous change in the way we deliver public health services to the vast majority of Americans. These changes require leaders with well-developed skills who will provide direction to a workforce that encompasses a thick culture of caring workers who want to improve health. These workers are still using outdated approaches that were successful in the past in order to solve new problems. The old tools and skills of public health workers will not work in solving twenty-first-century health dilemmas. Therefore, there must be change in the way public health departments work.

Successful leaders in public health must receive formal leadership training to produce change. These leaders must then be empowered to use the newly acquired skills to improve the health of their community. This is not an easy task, but it can be accomplished.

Bureaucracies

Empowerment

Leadership