Repeat Movements of Inanimate Objects

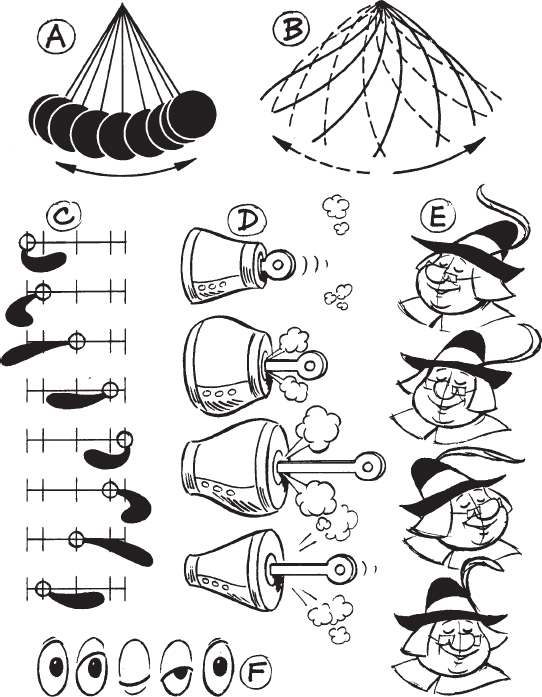

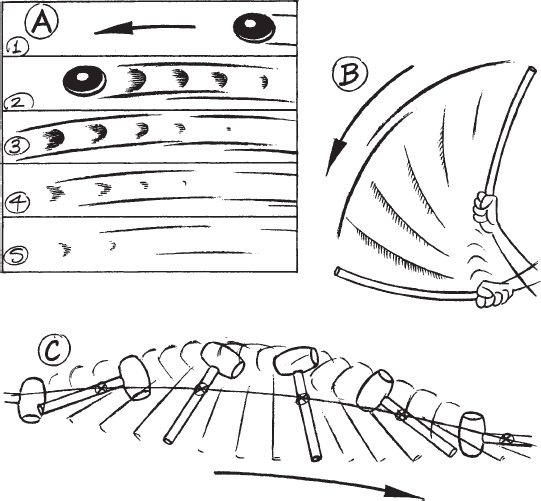

In straightforward to-and-fro movements, such as those of a piston or pendulum, it may or may not be possible to use the same drawings in the reverse order for the return movement. With a rigid pendulum (Fig. A) it would be possible, but with a cartoon piston (Fig. D) animated with steam pressure in mind, the drawings used for the forward movement would not work in reverse.

In any flexible movement, or that of any object which has something trailing, then a fresh set of inbetweens must be done for the two directions of movement (Figs B, C and E).

In a to-and-fro movement in which the same drawings can be used in reverse, an optical problem arises at the ends of the movements. Suppose the animation is done on double frames and charted: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 2, 3..., etc. it will be seen that drawings 5 and 2 occur twice, that is, they are on the screen for four frames out of six and so make a greater impact on the eye than the actual extremes, which in this case are 1 and 6. This effect can be avoided either by holding drawings 1 and 6 for four frames each, or else by missing out one of the exposures on 5 and 2, thus: 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 5, 4, 3, 1, 2, 3... etc.

A similar optical effect can occur with eye blinks if the same inbetweens are used on the way down as on the way up, especially in close ups. In this case it is better to space the two sets of inbetweens differently so that the same positions do not occur on both the opening and shutting movements.

Figure 49 A A straightforward swing cycle, in which the same drawings can be used for both directions of swing. B Flexible objects tend to swing more like this. C, D and E Short repeat cycles in which the same inbetweens cannot be used in both directions of movement. F An eye blink.

What are the main features of a ‘normal’ human walk? There can be as many walks as there are people. Does the character walk leaning forward or laid-back? With slumped shoulders or a posture that is ramrod erect? Does the character walk on tiptoes or on the balls of their feet or heels? Nose in the air or head down, deep in thought? What are the arms doing?

The walk is the first step to finding the key to a character’s personality.

To begin, walking has been described by the old animators as ‘controlled falling’, i.e. skilled manipulation of balance and weight. Most animators begin by animating their own walk, since it’s motion is already within their minds.

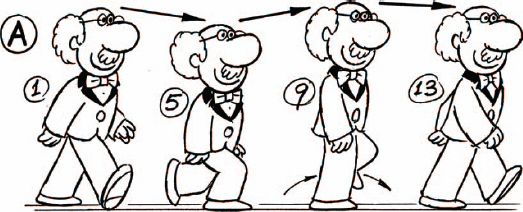

The only point in a walk when the figure is in balance is at the instant when the heel of the front foot touches the ground; the body weight here is evenly spaced between the two feet. This is usually the main key drawing (Fig. A). It gives the stride length, and so can be used for planning the number of steps needed for the character to cover a certain distance. This ‘step’ position is the one with the maximum forward and backward swing of the arms. It is actually the middle of the fall forward onto the front foot, when the front knee bends to cushion the downward movement of the weight. The key position here is usually known as the ‘squash’ position (Fig. A5). The body’s center of gravity is at its lowest point, and the front leg supports the body weight. The back foot is almost vertical and although the toe is just touching the ground, it bears no weight at all in this position. In Fig. A9 the bent leg straightens, lifting the center of gravity to its highest point as the back foot moves forward. This is the ‘up’ position and leads into the next ‘step’ at 13.

There are two slightly different ways of animating a walk—the choice is one of convenience. Suppose a character makes a 1.8 inch stride in 12 frames. Assuming that the walk is a repeat movement, then if we call the left ‘step’ drawing 1, this drawing will appear again 24 frames later (i.e. drawing 25 = drawing 1) 3.6 inches left or right of the original position (Fig. B).

So the intermediate positions of the walk can be animated between these two positions. The character can then advance along the cels, relative to the pegs, until it arrives back at drawing 1 at which point the pegs are moved 3.6 inches and carry on for the next two steps.

The alternative method (Fig. C) is to animate from drawing 1 back to drawing 1 in the same position, so that all the bodies in the cycle are superimposed over one another, with an up-and-down movement only, instead of advancing along the cels. The 3.6 inches, which the figure moves along every two paces, is now taken up by moving the foot backward 0.15 inch per frame. After 24 frames the feet have effectively slid back the 3.6 inches to make up the two steps. This is called ‘animating on the spot’ because to make a man walk by this method, the pegs carrying the figure remain static while the background pans backward by the same amount as the feet per frame.

Figure 50 A Part of a walk cycle, spread out for clarity. The complete cycle would be 1 – 23 (i.e. 1 = 25), 17 being the same as 5 with legs reversed, and 21 the same as 9. B The same cycle animated forward with static pegs. The pegs stay in position X whilst the figure moves forward on 1 – 23. The pegs then move to the right by the length of two strides and 1 – 23 is repeated in the new position Y. C A walk cycle ‘on the spot’. The body moves up and down whilst the heels slide backward along the scales at the same speed as the background pan. D Successive positions in a naturalistic walk. The left shoe is shaded black. Note that on 11 the left leg is straight just before making contact with the ground on 13 (see next page).

The up-and-down movement of the body should slow in and out of the key positions, but the forward movement of the body should be at a uniform speed, or the animation ‘sticks’.

It is important that there is just enough time for the straight leg to register on the screen in the ‘step’ position. As the front leg is bent both before and after this position, there is a danger that the eye will connect these two positions—missing the straight leg—with the effect that the character is doing a ‘bent-leg’ walk. Fig. D on the previous page gives another variation of this problem. It is based on a naturalistic walk, and the left leg kicks out straight on drawing 11, although it is still moving forward to the ‘step’ position 13. The front foot should slap down flat on to the ground quickly after the ‘step’ drawing. This loosens the ankle joint.

There are many variations on this walk. For example, in an aggressive walk the body leans forward, the chin is out, and the fists are clenched. In a proud or pompous walk the body may lean slightly backward, with the chest out and plenty of shoulder action, with the highest position on the ‘step’ drawing. In a tired walk the body and head droop, arms may hang loosely and the feet may drag along the ground, and so on. A double bounce walk can give a character the sense of youthful energy, a ‘street-sense’ feel, like a tough gang member. To achieve this, on each straight up pose add two additional frames of the character’s foot rising up on its toe, almost a small hop. This bouncing gait creates a natural swagger for the character that shows ‘attitude’.

Figure 51 Three different styles of walk: Top One step (12 frames) of a 24 frame cycle. Middle Key positions from a 48 frame walk through deep snow. On double frames two inbetweens are needed between each pair of keys. Bottom One stride of a 24 frame cycle on double frames. The two ‘step’ positions are drawings 1 and 13. The weight of the body squashes onto the front foot on 5 and rises as the back foot comes forward on 9. Note how the front leg remains straight on 3 to avoid the ‘bent leg’ look.

Spacing of Drawings in Perspective Animation

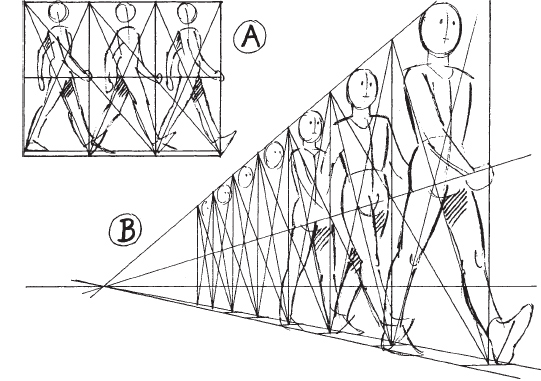

To animate in true perspective requires complex draughtsmanship and some understanding of the geometrical treatment of the subject.

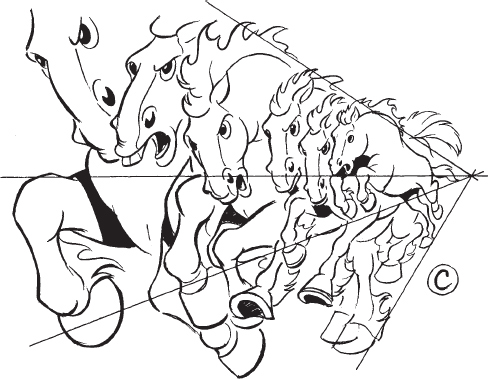

Especially when a character walks in perspective, an accurate perspective grid must be drawn giving the height of the character and the length of the strides, so that the animator has a clear idea of how the spacing of the strides gradually increases or decreases. It is quite a difficult animation problem to make all parts of a figure get larger or smaller and yet remain in the right proportions.

For dramatic effect when a character rushes toward or away from the camera, a low horizon is preferable. High horizons provide a more relaxed effect. In both instances the vanishing point must be established in relationship to the horizon, which represents the camera or the audience’s eye level. The increasing or decreasing lengths of strides must be worked out by defining measuring points for every few drawings. Estimation is possible, but must be plotted out carefully.

Figure 52 A Side view of imaginary grid constructed around successive ‘step’ positions of a walk cycle. B A similar grid to A, drawn in perspective. C A rapid perspective gallop. There was one drawing in between each pair of positions.

Variation in perspective can be achieved by lowering the horizon and changing the vanishing point during animation. This, however, requires some experience. Weight must be evident in all perspective animation. In a perspective shot, a character can run from the foreground over the horizon in a few frames, approximately 12 to 16, provided the right degree of ‘anticipation’ is given. Because of the speed of the action, it is better to use single frame animation.

Effective animation requires movement in space and an illusion of three dimensions, otherwise the characters may appear to be too flat. Take advantage where possible of opportunities for movement in exaggerated perspective. For instance, if some part of a figure or object swings round close to the camera, emphasize the increase in size in the drawings.

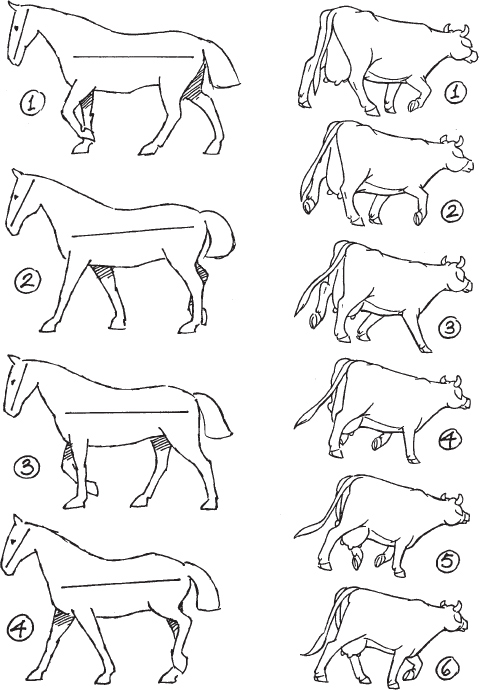

Figure 53 In a normal walk, a horse’s front legs step half a pace later than the back legs. The body and head tilt slightly as a result of the alternate stepping of the back and front legs. On the right, a cow walking, from Animal Farm.

The order in which the feet of a horse touch the ground is: back left, front left, back right, front right, back left, front left, back right, front right, etc.

A horse normally takes about a second to make one complete stride, i.e. from ‘back left’ to ‘back left’. If it is walking freely the feet touch the ground at equal intervals of time.

If 24 frames are taken as the length of a walk cycle, i.e. back left hits the ground on frame 1, ‘back right’ hits the ground on frame 13, and ‘front left’ and ‘front right’ hit the ground on frames 7 and 19 respectively.

In the step position on the back legs, on frames 1 and 13, the back legs form two sides of a triangle. The rump is lower than it is on frames 7 and 19, where one leg is vertical as the other one passes it. The shoulders are lower on frames 7 and 19 than they are on frames 1 and 13 for the same reason. This causes a slight rocking movement to the line of the horse’s back. Also on the front step positions, as the shoulders go down, the head is pulled into a slightly more horizontal slant than it is on frames 1 and 13.

Other quadrupeds, like cows, are surprisingly similar in the timing of their walk to a horse. The order of the feet is usually the same and the movements of the back and the head follow the same pattern.

An elephant may take a second or perhaps a second and a half to make a complete stride, whilst a smaller animal such as a cat may take a complete stride in half a second or less, although these timings may vary greatly.

Some animals, such as the deer family, lift their feet high when walking; cats also do this when stalking. There is no equivalent of the ‘squash’ position of a human walk in a four-footed walk, as the back foot of each pair usually comes of the ground immediately the front foot is on the ground.

Predators of the cat family (lions, cougars, housecats) possess a more flexible dorsal construction in their spine. This gives their motion a wiry grace and the ability to change direction very rapidly. Because felines have more of a radius bone in their front forelegs than dogs or cows, they can turn their paws inward (pronator-supernator action).

A walking animal spends roughly half the time supported by two legs and the other half supported by three. A four-footed animal starting a walk usually starts with one of its back legs, followed by the front leg on the same side.

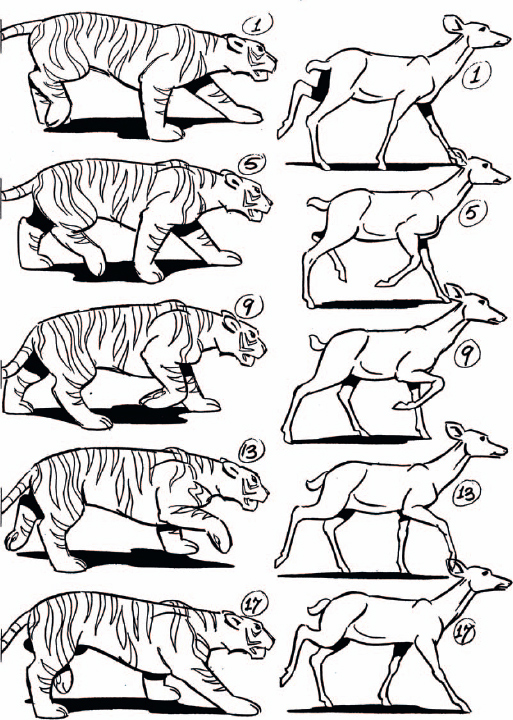

Figure 54 Parts of cycles of a tiger and a deer walking. In both cycles drawing 17 has the opposite feet positions to drawing 1, so the complete repeat would take 32 frames. Although the length of stride is the same in both these examples, note the difference in feeling. The tiger has a crouched menacing attitude, whilst the exaggerated lift of the legs helps the deer’s motion to be bouncy and light.

A horse increases its speed from a walk, to a trot, then a canter and finally to a gallop, at which it travels at maximum speed.

In the gallop a complete stride takes about half a second, and the order in which the feet hit the ground is: back left, back right, front left, front right—pause—back left, back right, front left, front right, etc. The back legs make the same movement as each other with a slight time lag and the same happens with the front feet. The big push is given by the front feet and after this push the animal becomes momentarily airborne.

In some animals, for instance the cat, the bigger push comes from the back legs and the cat becomes airborne after this movement. The shoulders and rump rise and fall giving a rocking movement to the line of the back, and the head is tilted at a slightly more horizontal angle as the shoulders go down and the front legs take the weight. The spine itself also flexes and extends. This is very noticeable with a cat, as when the back legs come forward a pronounced hump appears in the lower half of the back, and as the back legs push the body into the spring, the spine stretches out into a reverse curve. The movement of the hip joint comes strongly into play in a gallop and the forward and backward movement of the thighs, combined with the bending and stretching of the spine, gives the impression that the animal’s body is alternately lengthening and shortening. When the big leap comes from the back legs, as with a cat, the order of feet hitting the ground is: back left, back right—pause—front right, front left, back left, back right, etc. The complete stride of a cat takes about { 1/3 } second.

Figure 55 The flexibility of the pastern or wrist joint of a quadruped during a gallop is particularly noticeable. This joint can bend backward into almost a right angle as it takes the weight of the animal (drawings 1 and 7), and can also bend into almost a right angle the other way when relaxed and the foot is in the air (drawings 2, 3, 5, etc.).

Birds are well adapted to fast movement through the air. They are streamlined and waste the minimum amount of energy in the air. The body enhances the movement by lying in the direction of the airflow. The legs are tucked up or trailed in flight.

The aerodynamics of bird flight is very complex and it is unnecessary to go into detail. The power stroke is the downward stroke against the cushion of air beneath the bird, and during it the air resistance closes the feathers and the wing makes as large an area as possible, to maximize the thrust. Birds have very large chest muscles to power the downstroke. The muscles controlling the upstroke are much smaller, as the air resistance is much less. During this stroke the wing folds partially to present a smaller surface area and the feathers tend to separate like vanes to allow the air to pass between them. The body is usually tilted slightly upwards at the head, is lifted slightly during the downstroke and falls again during the upstroke.

In normal flight the wing strokes are not straight up and down. The direction of beat is slightly backward on the upstroke and slightly forwards on the downstroke. This is the opposite of what might be expected for forward flight, but the forward impetus is actually given by the tilt of the wing surfaces. This forward and backward wing beat is particularly noticeable when the bird is hovering (the body may be almost vertical and the wing beat almost horizontal) and also when the bird is rising or coming in to land.

During a flying cycle, the upstroke and the downstroke take about the same time although with larger birds at least, the downstroke is slower. The length of the repeat depends on the size of the bird. On the whole a large bird moves more slowly than a small one. For example, a sparrow may make 12 complete wing beats in a second, whilst a heron or a stork may make only two.

Figure 56 A A pigeon hovering as it comes in to land, from Animal Farm. Note the upright position of the body and the circling movement of the wings. B 1 – 9 is a repeat flying cycle. The body dips slightly in the air on 1 and rises slightly on 6 as the wings press downwards. The wingtip feathers radiate from the ‘wrist’ and trail backward in the direction they are coming from to give flexibility. Note how these feathers separate on the upstroke—7 and 8—to allow the air to pass between them.

Drybrush (Speed Lines) and Motion Blur

Drybrush (speed lines) and motion blur are ways an animator illustrates the optical blur the eye sees when an object is moving too rapidly to be seen clearly. In traditional animation, the speed line is a throwback with its origins in the graphic representations of rapid movement done in early newspaper cartoons. In later cartoons the speed line was replaced by drybrush.

This was a smeared drawing created by the cel painter by dabbing excess moisture from the paintbrush and streaking the character’s colors in the direction of the line of movement. In digital animation the same effect is done by using the control that adds a motion blur. This effect creates a blur of the action similar to the blurry images of rapid action in live action photography.

Figure 57 A Speed lines disappear where they are formed or move in a slightly opposite direction to that of the object causing them. B and C Speed lines left by rapidly moving objects. D A character zooms of screen. E A more elaborate drybrush trail, taking 16 frames or more to disperse. This would also move in the opposite direction to that of the character causing it.

While drybrush is an effect painted right onto the individual frames, the motion blur is an effect that is turned on in the computer. The motion blur does not appear in any single frame; it is always on and reveals how a character moves between frames. One may even want the blur to be visible, so it would match the well-known appearance of a live action film. This can be achieved by increasing the distance between the frames movement. Aesthetically, some still prefer the graphic approach of the speed line or drybrush, even in digital work. It remains a creative choice.

Drybrush (speed lines) should be timed quickly so that by the time the audience is aware of it, it is gone. Using drybrush for three frames is about the minimum effective length, but some spectacular examples can extend to 16 frames or more. The important factor to remember is that drybrush is something left behind by the object causing it. It must not move with the object as this gives the impression of threads attached to it.

If a stick swishes through the air and two consecutive drawings are widely spaced, the drybrush would consist of curves, carefully drawn in the direction of the swish, and a number of lines representing several in-between positions of the stick. These would all be put on cel in the color of the stick. On the next few drawings, this drybrush would be animated away (i.e. diminished to zero) in the same place as it originated, or moving very slightly in the opposite direction to the stick. In the meantime, further drybrush may have appeared. This would be animated out in the same way.

Figure 58 The whipcrack is all on single frames. The accent is on drawing 5, where the curvature of the whip reverses. In the gunshot, drawings 2, 3, 4 and 5 are single frames. 6 and 7 are double frames, with perhaps two or three more inbetweens slowing into the hold on 8. The accent is on drawing 4.

Drybrush should be used very sparingly and should be saved for situations where drawings are so widely spaced that the eye has difficulty in connecting them up. If the spacing of drawings is well done and fast action well anticipated, the eye accepts very widely spaced drawings without trouble.

A more spectacular drybrush effect might be used when a character runs of screen. For example, if a character is about to zip of right, he anticipates to the left, accelerates to the right and goes off very fast. This may not work without drawing in some drybrush streaks as he runs of, moving them rapidly to the left and following each other in a series of eddies. This can easily be continued for 16 frames or so, but must move rather quickly.

In order to emphasize a movement, the introduction of a visual effect is sometimes advisable. Such an effect does help to draw attention to the point the animator intends to make, especially if the movement is a quick one. The effect, however, must be a visual complement to the movement and should grow out of the type of action on the screen. It should also be quick and not labored, which could easily spoil the whole effect.

In the case of the fight sequence between the farmers and the animals in revolt in Animal Farm such extra effects were introduced to heighten the sequence’s dramatic excitement.

The farmer’s whipcrack, for example, was a sequence of eight drawings on single frames. At the accent of the movement, which was where the curvature of the whip reversed direction, a three frame, white ‘crack’ effect appeared (see page 114). The accent of the gunshot movement was where the gun barrel suddenly recoiled. The shot itself was made visible by a strong ‘swish’ effect followed by a slower puff of smoke as the gun barrel came forward again.

Since every situation is different, it is best to make any decisions about visual effects during the process of animation.

Figure 59 A This wheel cannot rotate in less than 20 – 24 frames. B This one can. C So can this. D This ladder is moving to the right, but the rungs will move to the left. E Beware of equally spaced vertical lines on panning backgrounds. F Two examples of stroboscope discs. G A zoetrope strip.

Strobing is an effect which is an integral part of the mechanism of the cinema. Indeed the stroboscope, invented in 1832, was the first device used to present the illusion of a moving picture. The reflections of images on a spinning disc were viewed through slits around the edge of the disc so that a series of static images were seen in quick succession. A similar device, using the same principle, was the zoetrope in which paper strips were viewed through slits in a rotating cylinder.

Strobing is liable to occur in the movement of an object, which has a number of equally spaced similar elements. Some examples are the rungs of a ladder or the spokes of a wheel.

If a drawing of a ladder has rungs drawn 1 inch apart and the ladder starts to move along its length at an increasing speed, all is well until the amount of movement on the ladder is just under ½ inch. At this point the rungs begin to flicker and when the ladder moves up exactly ½ inch per frame, the movement is completely confused. This is because the eye sees a set of rungs on one frame and on the next frame it sees a set of rungs halfway between those on the first frame, and does not know whether the original rungs have moved to the right or to the left. On the next frame again, the rungs on the first frame have moved along 1 inch and so are superimposed over the rungs on the first frame. This gives the impression that the rungs are flickering on and of on alternate frames. If the movement is more than ½ inch, say 0.7 inches to the right, the eye jumps across the shorter gap and the rungs appear to move 0.3 inches to the left. This is the reason for the well-known illusion of stagecoach wheels appearing to turn backward.

The best cure for this strobing effect is to avoid situations where it may occur. The spokes of a wheel should be as widely spaced as possible. One time-honored solution is to have one broken spoke so that the gap can be seen rotating. Another way of overcoming this problem is to show the rim of the wheel rotating, but depict the spokes themselves as whizzing round with a drybrush effect.

A wheel, or ladder, always animates comfortably in the direction required if it moves by up to one third of the distance between one spoke, or rung, and the next. At faster speeds, if the broken rung dodge does not work, either avoid the sequence altogether, or work on it with drybrush to suggest the speed at which it is going.

Strobing can also occur on background pans (see opposite).

An eight frame run cycle—that is four frames to each step—gives a fast and vigorous dash. At this speed the successive leg positions are quite widely separated and may need drybrush or speed lines to make the movement flow. Drawing 5 shows the same position as drawing 1 but with opposite arms and feet. Similarly drawings 6 and 2, 7 and 3, and 8 and 4 show the same positions. These alternate positions should be varied slightly in each case, to avoid the rather mechanical effect of the same positions occurring every four frames.

A 12 frame cycle gives a less frantic run, but if the cycle is more than 16 frames the movement tends to lose its dash and appear too leisurely.

The body normally leans forward in the direction of movement, although for comic effect a backward lean can sometimes work. If a faster run than an eight frame repeat is needed, then perhaps several foot positions can be given on each drawing, to fill up the gaps in the movement, or possibly the legs can become a complete blur treated entirely in drybrush.

In the first example, drawing 4 is equivalent to the ‘step’ position in a walk, with the maximum forward and backward leg and arm movement. In a run it is also the point at which the centre of gravity of the body is farthest from the ground, that is, in mid-stride. In drawing 1 the weight is returning to its lowest point, which is in drawing 2. In drawing 3 the body starts to rise again as the thrust of the back foot gives the forward impetus for the next stride.

Figure 60 These are both examples of eight frame run cycles. This means four drawings to each step. Drawings 1 and 5 show the same leg and arm positions but with opposite feet and so do 2 and 6, 3 and 7, 4 and 8. In such a short cycle these positions should be varied slightly to avoid a mechanical effect.

Character animation is the ultimate achievement of animation art. It is a complex combination of craftsmanship, mastery of the science of natural movement, acting and timing. When successful, it can feel to the animator like an Olympian moment of creation. The artist not only fulfills the needs of the performance as indicated by the script, but they are also responsible for the birth of an independent personality—a Bugs Bunny, Ariel the Little Mermaid or Bart Simpson. The characters’ appeal is much more than just the voice actors’ tones, the writers’ wit, the animators’ technique or the designers’ style. They are the sum of all their parts. And when done successfully, the audience comes to know the character better than their own families and friends. You have it in your power to create memories that people will cherish for decades after.

Characterization in animation is concerned not so much with what the characters do, as how they do it. The old vaudeville (music hall ) adage was ‘It’s not the opening of a door that is funny, it’s when you open a door funny’. The audience is conditioned to look at human characters in human situations. In animation this can only be a starting point. The cartoon character should not behave exactly like a human being. It would feel and look wrong. Human reactions and human actions must be exaggerated, sometimes simplified, and distorted in order to achieve a dramatic or comic effect in cartoon. Good character animation is not merely the copying of life—it is the caricature of life, life plussed.

Figure 61 Facial expression is an important part of characterization, but use the whole body to express feelings and emotions. The drawing of a character can be adapted to meet the needs of mood—in benevolent moments a character would be drawn in soft, curved lines; when more aggressive the drawing would become rather angular with more straight lines; when afraid he or she would shrink back and become more spiky, their hair standing on end, and so on.

Figure 62 Two extremes of mood. On the left, animated on double frames, abject misery because the character has been rejected. On the right, general mayhem caused by the character being given a live electric plug to hold.

For these reasons the features of characters must be kept simple, allowing for maximum facial expression. The key positions should be sufficiently expressive, and held for a long enough period of time, to transmit the message to the audience. In animation, such transmission is easier in movement than in live action. When a movement is over-exaggerated it tends to create a sense of comedy. This is especially the case in fast movement. A deliberate exaggeration of speed, therefore, is the basis of timing for caricature as, for instance, in the case of Tom and Jerry cartoons. Slower pacing requires greater emphasis on expression and characterization of the subject. It requires more subtle animation, and it is infinitely more difficult to handle.

In the beginning we all animate ourselves, because we understand most intuitively how we would do actions and solve problems. Acting means to put ourselves into another’s mind to see how they would solve problems. How would I move if I were a Sumo wrestler? A ballerina? A Wall Street tycoon? An elderly person leaning on a walker? Not only would all of these characters move in a different way, but even the tempo of their movements would be different. Some of the old Disney animators used to work with a piano teacher’s metronome on their desks. This enabled them to assign a particular tempo to a planned animated character.

Many animators augment their animation training with some course in acting and/or mime. To expand their technique, animators also studied the same principles that great teachers such as Constantin Stanislavksy and Lee Strassberg wrote for flesh and blood actors. What we are doing on screen is in fact acting, except instead of using our bodies as our means of expression, we use our drawn characters.

The Use of Timing to Suggest Mood

The creation of mood is the stock-in-trade both of the cinema and the theater. It is also important in animated films but, as animation is a medium of exaggeration, it is advisable to avoid subtle shades of expression.

In general terms, the moods of depression, dejection, sorrow, etc. depend on slow timing for their effect, whilst the moods of elation, joy, triumph and so on depend on quicker timing. Other moods, such as wonder, puzzlement and suspicion may depend on facial expression and body posture. The aim is always, however, to convey to the audience the mental state of the character, and match this to the mood of the backgrounds, the camera movements, and everything else which contributes to the visual effect on the screen.

To express depression, the character must appear to have no energy. His body droops forwards, his head hangs on his chest, his knees sag, and his movements are slow, with frequent long holds and sighs. Anything that can be used in the drawing to convey the feeling of depression should be used—the hair and clothes hang limp, perhaps the hat sinks down over the ears, and the shoes squash with the extra weight of gloom.

Elation and joy, on the other hand, need plenty of energy, which gives quick, bouncy movements with the character frequently airborne. The body is upright or curving backward, with hair and clothing springy, and a general lightness of step.

Suspicion requires a deliberate expression of puzzlement and cannot be hurriedly timed. Give enough time for the audience to read the facial expression of the character and animate his hands for further emphasis if there is time.

Synchronizing Animation to Speech

Unlike live action films, where the dialog is simultaneously recorded with the action, in animation it must be recorded beforehand so that the movement can be fitted to it precisely. It is an essential pre-production operation, which cannot be left until after the completion of animation.

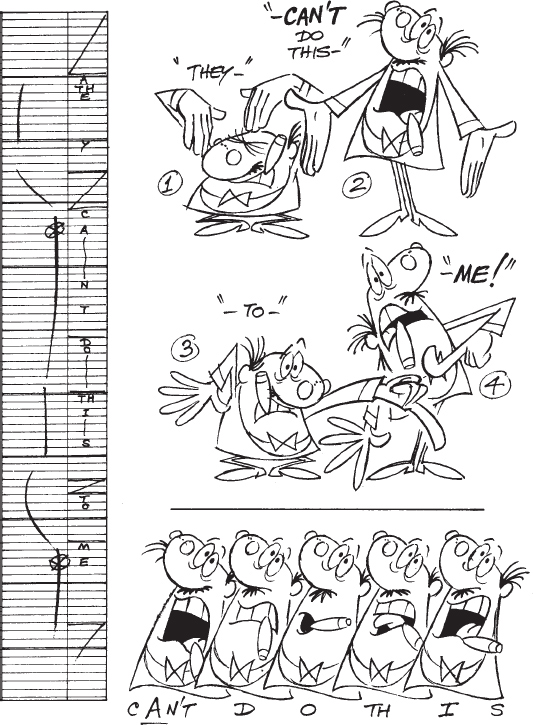

Once the soundtrack is available (either on tape or digital file), the type and character of the voice can be analyzed through the use of a synchronizer (16mm or 35mm) and a frame-by-frame timing guide for the animation can be made. This can be done either on the exposure chart, where there is a special column for it, or on a separate chart. In either case, it must be done in terms of frame analysis. No two dialog performances are the same. Even single words like ‘you’, ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘its’, ‘had’ can vary substantially when analyzed in terms of separate frames. Such information is the basis of fitting animation to sound.

Firstly, listen carefully to the soundtrack and in particular to the feeling behind the way in which the words are spoken. Then listen to the phrasing and rhythm of the speech and find the positions of the main emphasis and key words. Then plan the movements of the character’s body, head, arms, etc. to fit the words and the way in which they are being said, to reinforce the dramatic effect. Try to emphasize the main points of the speech with the whole body, if time and budget permit it. In animation, the meaning of dialog should be somewhat overemphasized, especially in an entertainment film.

Figure 63 An emotional impresario speaks the line: ‘They can’t do this to me!’ The broken, wavy line on the phonetic breakdown strip represents the pitch and volume of the voice. The important accents in the soundtrack are on ‘can’t’ and ‘me’ so the pattern of movement should emphasize the vowels in these two words.