14 Relating to the Subject

Of this Berenika Zakrzewski portrait Douglas Kirkland says, “I arrived with two assistants at the New York Studio on an extremely hot, humid day after working outside on a different project. The transition wasn’t simple, bringing the lights and equipment in and setting up quickly, but after adjusting I found myself in a new mindset with the concert pianist Berenika. Everything we did earlier in the day went behind me after speaking with her and listening to her radiant music on the piano. Once more I learned the lesson on how important it is to pick yourself up and find the positive side of any project, falling in love with your subject and working towards the most positive end. For me this is truly the joy I find in all the work I do as a photographer. It is important to always do your best at all times and always care about what you do.”

© Douglas Kirkland (Courtesy of the artist)

If you don’t like people, portrait photography is not a wise choice for your photographic career. Unlike several other areas of photography, portraiture is personal. It is based on the interaction between the subject and the photographer. Portrait photography is a conscious act that involves cooperation on the part of both the subject and the photographer. Since this chapter is about relating to others, we also do so by including references and quotes from other authors and photographers.

We can think of making a likeness mechanically, e.g., a driver’s license photograph where the relationship is between the subject and the camera. In this case the operator, usually the clerk who took your application and money, has you look at a spot on the camera. The camera is activated regardless of the expression on your face, and the light is straight on so that there are no shadows. The background is a color used for identification only.

With portraiture, the idea is to use the likeness to communicate something about the people in the portraits, their personality, their essence. For this reason, it is necessary to have a relationship between a photographer and a subject rather than a subject and a machine. Even if the photographer has a recognizable style and intends to use it, the portrait is still about the subject—and the photographer needs to communicate this to the subject.

In most cases, the photographic process involves a collaboration between strangers. The success of the portrait lies in the ability of the photographer to evoke the best pose and emotion. The subject needs to relate to the portraitist to allow the best views to be captured.

Further, the relationship between photographer and subject often becomes part of the style of the artist. For example, Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, and Arnold Newman had much in common, including similar backgrounds and living locations. Their skills were all at the apex of portrait photography, yet their portraits are very different. Penn’s portraits show a relaxed feel whereas Avedon’s are edgy. Newman said his style of portraiture was “90% moving furniture,” i.e., creating the environment. These styles reflected their personalities as well as the relationships they had with their subjects, the sum total of which translated into their portraits.

Gender and age also can play a role in the success of a portrait. There are frequently affinities and/or abilities to relate to a subject based on gender. For this reason some photographers make stronger portraits of women while other photographers make stronger portraits of men. Likewise, some photographers are wonderful with children while others have a harder time working with them.

Though photographic portraiture is based on a relationship that is, in fact, a collaboration, the accountability for the session falls to the photographer. It is the interaction between photographer and subject that makes a substantial difference in the success of the portrait. To be continuously successful, the individual choosing photographic portraiture as a primary working style must have a desire to work with other people.

The complete photographic portrait process has three parts that all interact with each other. First, the subject and the photographer interact from an original contact; then the portrait is made; and finally, there is closure/delivery. The overall success of the photographic enterprise depends on all of the relationships within each part of the process. If the interaction at the beginning, i.e., the original contact, goes poorly, then the rest of the process may not happen. A subject to whom the photographer is a stranger will most likely reject having a portrait made if the first meeting is not successful. Remember, you have only one chance to make a good first impression.

© Christine Trice (Courtesy of the artist)

After the first contact, if the subject chooses to have a portrait made, the photographic session needs to continue the good relationship in order to reach completion. Throughout making the portrait, the critical issue is comfort. This comfort goes beyond the physical comfort of poses to include the effects of the totality of the session. While there may be times when the photographer wishes to evoke a less than comfortable expression, if the session is too uncomfortable, the subject may not continue.

Lastly, the closure of the process requires respect for the subject. For many photographers, closure happens shortly after the photographic session. The reason is that when subjects are totally involved in the making of the portrait, they are more likely to purchase.

Though commercial and celebrity portraiture may seem different, similar concepts apply. In these types of portraiture, the contact may not be with the subject but rather with a representative of the subject for final use media. The first contact with the subject may not occur until the actual photographic session, and fulfillment may well be with the original contact and not with the subject. With portraits for advertisements, there may even be a third collaborator: the art director, who has a specific use for the portrait and thus specific expectations as to how the portrait will work. The subject will just arrive at the session, and that contact will be the only time the photographer interacts with the subject. It is not unusual for a celebrity’s agent or assistant to keep looking at their watch to ensure that the portrait session does not exceed the allotted time.

Confidence

Regardless of the approach, purpose, or style of the portrait, the issues of comfort and respect for the subject remain paramount. The subject’s comfort is largely determined by their level of confidence in the photographer and the process. Confidence and trust are the linchpins of the relationship needed for portraiture.

There are several ways that confidence can be generated in the various parts of the portrait process. The easiest is if the subject relates well to work that the photographer has already produced. When the subject can recognize himself or herself in previous work, then he or she develops confidence that the photographer can produce the type of portrait desired. Therefore, it is necessary to interact with subjects and determine how they see themselves. Whether through images on a web page or on the walls of the studio or through word of mouth, how the photographer is perceived prior to the initial contact can start the process with confidence.

Introductory meetings and interactions allow confidence to grow through conversation, actions, dress, body language, humor, and consideration for the wishes of the subject. The actions that do the most to build or retain confidence are knowledge appropriately demonstrated, the photographer’s self-confidence, preparation for each part of the portrait process, and a calm demeanor.

© Judy Host (Courtesy of the artist)

The portraitist needs to exhibit the confidence that comes with being proficient with photographic technology. Photographic/technical equipment needs to be a seamless extension of the artist’s mind. Separate but equally important are the aesthetic aspects of the portrait process. Through the examples on the walls, the care and attention to styling, and the way design concepts are discussed, the artist can demonstrate his or her command of the aesthetic portions of the portrait experience.

Part of the success of the process lies in how the photographer is perceived by the subject. Appropriate dress and actions set the parameters for success, whereas inappropriate dress and actions can distract from the portrait process.

Comfort

Douglas Kirkland said, “Your job is to make people as comfortable and calm as possible.” In the totality of the portrait-making process, the subject’s comfort leads to a high level of confidence in the photographer. A major influence in the creation of comfort for the subject is calmness. The idea of being calm is not to show a lack of enthusiasm, but rather to ensure that your demeanor does not create an uncomfortable situation.

While we can easily see comfort as a product of the photographic location, temperature, light levels, posing equipment, etc., the most important factor is the rapport between the photographer and the subject. According to Tony Corbell, “You try to put them [the subjects] at ease. You can do an awful lot for yourself and for them by getting to know them before the shoot. Spend time talking to them before the shoot; do not just walk straight into the studio and start shooting.”

In a recent lecture, photographer Joyce Tenneson spoke about her approach to putting the subject at ease. “Even if I am in a dumpy place, I have one beautiful flower... something of beauty. Or a beautiful candle with a fragrance, or something that’s welcoming to the person, with a glass of Pellegrino or a glass of wine. I greet my clients when they come in with something of beauty, and I am theirs, 100 percent. So I’ve done all the work before they come. The lights are set up, everything is tested, I have done some kind of a phone interview or research so I know what they’re looking for. I’ve gotten it. If it is an author who is overweight and is really frightened of what he or she is going to look like in front of the camera, I know how am I going to put that person at ease.”

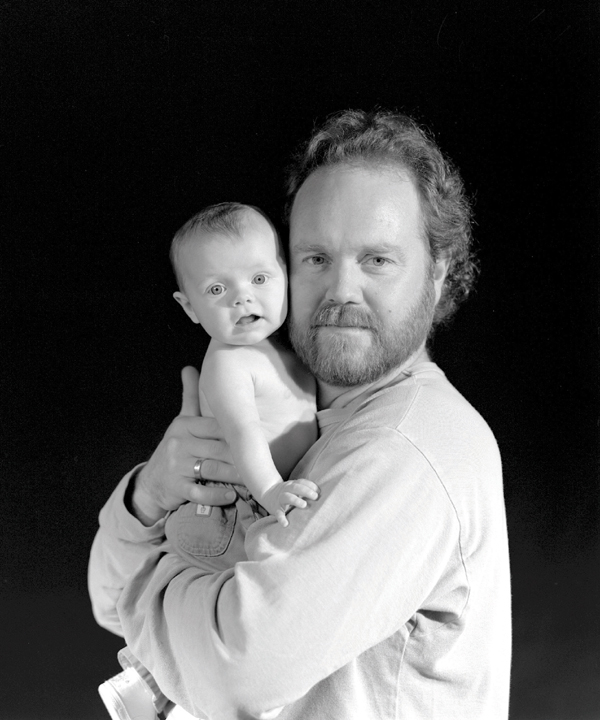

© David Williams (Courtesy of the artist)

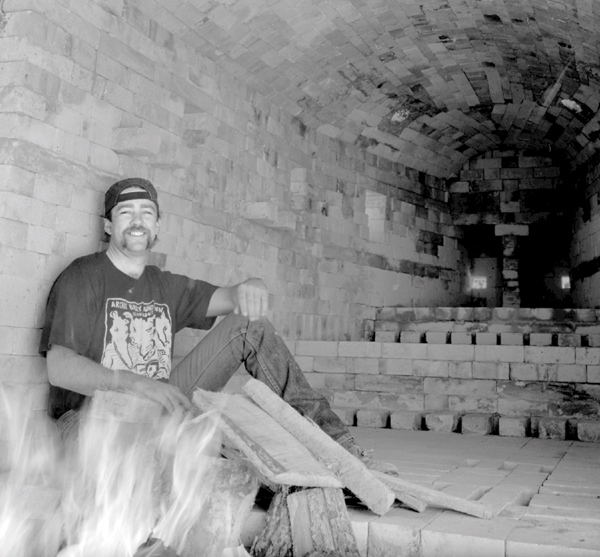

© Paul Tumason (Courtesy of the artist)

This can be done even with celebrities who have little time scheduled for the portrait sitting. With the studio ready, time can be taken to relax, communicate, and build comfort. Many photographers build rapport with their subjects simply by taking the time to talk with them—not about the portrait, but just relaxing conversation to build trust, create comfort, and develop a communicative link. Tenneson finds that researching the subject first, speaking about family issues, and opening herself up personally builds trust and comfort for the subject.

Part of developing rapport is sharing enthusiasm with the subject. When the photographer is enthusiastic about the portrait session, then the subject can relax about the process. Sharing enthusiasm and giving 100 percent attention builds the trust that is needed to direct the subject during the photographic session.

Analysis of the subject for facial lighting and posing choices is best done before the photographic session starts. When working with celebrities, the analysis can be based on previous images. With a “stranger,” the time for analysis may need to be at a meeting before the photographic session. The analysis needs to be done, but it should be subtle. The ability to work smoothly and effortlessly once the photographic session begins, without experimentation to solve lighting needs, establishes confidence.

There may be times when stress or angst is desired as an emotion. The comfort level of the subject may allow an interaction that is needed to capture the desired portrait. Richard Avedon would escort the subject toward the studio and then stop and talk. He would sit in a comfortable chair while the subject would sit on a hard bench. While talking, Avedon would analyze the subject’s face until he recognized the person was at the level of comfort desired. He would then move the subject to the studio and start the photographic session.

As the portrait process moves to the photographic session, the subject’s comfort and confidence will build if the process is controlled. If an assistant is available, you can have a relaxing conversation with the subject while the assistant does a basic setup for the lighting and any backdrop or set arrangement. Ideally, the conversation should not be held in the photographic space. If you are working alone or unable to segregate the photographic space from the meeting space, preset the space as much as possible.

A particularly good time to build confidence and instill a sense of ease in the subject is when something goes wrong. Cameras jam, lights do not flash, props fall—these things happen, and the calmness with which problems are handled adds to the comfort of the subject. The requirements include the ability to think on your feet and prepare for the unexpected. Stay calm and collected, regardless of what happens in the photographic session.

In addition to mechanical problems, other problems can undermine credibility. For example, while the photographer may do everything correctly, an assistant’s inappropriate actions may have a detrimental effect on the photographic session. If an assistant is slovenly or inconsiderate, it can damage the confidence that was previously developed.

Whether analysis of the face is done at the meeting before the photographic session or through research, this information will allow you to set lighting and exposure as well as give direction to make a successful portrait.

© Glenn Rand

To take the best advantage of the lighting and setup, the photographer will need to give direction and set the pose for the subject. Usually this involves verbal direction for moving or placing the subject’s body or face in a particular orientation. There are times when touching is required, but posing the subject via physical contact is a separate issue. Some subjects and photographers are comfortable with touching for posing, and others are not. Beyond a calm, confident demeanor, there is a need to direct people without being offensive or insulting.

Regardless of the style of direction used, most portrait photographic sessions are fluid. Small movements give the opportunity to finely tune the base portrait. As these small changes happen, the calmness and confidence of the photographer and subject make the session move smoothly. While there may need to be firm direction, it must remain calm and not domineering.

During the photographic session, the attention of the subject may wane and adversely affect the outcome. There are clues to this situation. The subject’s eyes provide good evidence of the engagement of the subject in the session. Lack of eye contact may indicate either shyness or disengagement; however, there is a point where the photographer may need to call on the rapport previously created with the subject to complete the session.

While not universally recommended, there are times when aggressive actions produce desired results. When Yousuf Karsh made his iconic 1941 portrait of Sir Winston Churchill, he set up his camera to photograph Churchill at his desk with his back to the camera. Just as Karsh was ready to make the image, he grabbed Churchill’s cigar. As Churchill turned and glared at Karsh, he pressed the shutter release and captured the image of a resolute Churchill. A similar technique has been used in recent times by Jill Greenburg to capture pictures of children crying. However, she took their candy rather than a cigar.

Author and photographer Bill Hurter suggests that the inability to hold a pose can be a dead giveaway that the subject is disinterested or distracted. Both the subject and the photographer need to remain focused during the portrait session to make the portrait a success.

In some situations, mostly in high-end or celebrity portraiture, a stylist is responsible for the makeup and attire. However, it ordinarily falls to the subject to prepare for the portrait session. Ensuring that the subject is ready to change their look, if necessary, also adds to the comfort of the photographic session.

Fulfillment

When the portrait is complete, the relationship with the subject needs to continue—even if there is nothing more to do than deliver the finished prints. It is vital to understand the long-term implications of the effort put into the relationship. For a portrait studio, it may be future print sales; for an editorial portraitist, it may be future assignments; and for the fine artist, it may be future projects. Experience shows that a successful portrait session leads to continuation portraits. Therefore, an experience with a subject that is successfully fulfilled may lead to revisiting the relationship through further portraits.