1 A Very Brief History of Photographic Portraiture

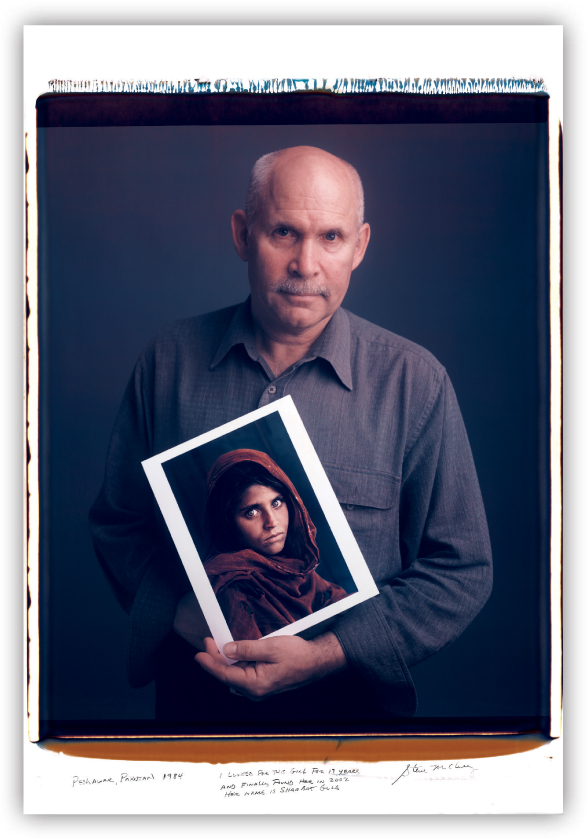

In this portrait from Behind Photographs, Tim Mantaoni made portraits of famous photographers with one of their best-known images. Steve McCurry made the portrait of The Afghan Girl in 1984; Mantaoni shot his portrait in 2002. Both of these portraits were used on the cover of National Geographic magazine. As part of the project, Mantaoni asked the photographers to write their comments about the photograph on the border of the image. © Tim Mantaoni (Courtesy of the artist)

Peshawar, Pakistan, 1984.

“I looked for this girl for 17 years and finally found her in 2002. Her name is Sharbat Gula.” —Steve McCurry

When we enter a discussion of the history of portraiture, we need to understand that we are looking not only at what has come before, but also at trends that will be used again. An examination of portraiture over the past 2,000 years shows many ideas that are still used in photographic portraiture. We are not saying that the portraiture of the past is what we should do, but rather that the ideas and approaches important throughout history are still finding currency today.

It must also be noted that our approach to portraiture is through Western eyes. The approaches of other societies are certainly valid, but our historic trail winds its way from Egypt through Europe to the Americas.

From prehistoric times, humankind has used pictures to describe, communicate, remember, and celebrate. The portrait was a natural extension of these uses. As societies developed, important individuals soon became the subjects of pictures. Historical portraiture is replete with changes in style and technique as societal conventions dictated how people would be portrayed. During many periods, portraits were idealized to convey the importance rather than the reality of the person.

Our only knowledge of portraiture in antiquity comes from the archaeological record. Sculpture and bronze statues are among the best records of Western portraiture in the pre-Roman era. This record indicates that only the elite upper or ruling class had portraits commissioned. Some of the earliest known portraits date from the first century BC. They were funerary portraits, created by the Egyptians of the Fayum district. Known as “mummy portraits,” they were used to remember the deceased and thus were painted with care to create the best possible likeness. The artists used light to create dimension in these portraits, displaying an advanced understanding of shadowing as well as specular and diffuse highlights.

Many portraits were produced in Europe during the medieval period, but their relevance to photographic portraiture is more ideological than practical. For much of this period, the church dominated portraiture, and likenesses associated the portrayed individuals with God or the church rather than conveying their personas. Since the church served as the preeminent supporter of the arts, its dictums determined a great deal of the content and thus medieval portraiture tended toward ecclesiastic subjects.

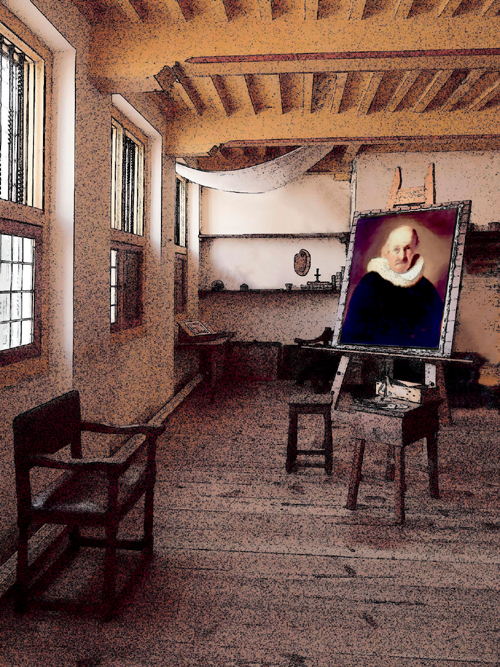

Dr. Munro by D. O. Hill and R. Adamson (From the collection of David Ruderman)

Rembrandt’s studio had a row of windows on the north side of the room that provided consistent diffuse light. With the subject situated near the east wall, the light would come down at a steep angle from the subject’s right side. A white cloth hanging above the easternmost window created overhead soft light. He likely closed the lower shutters on many of the windows to control the direction and overall intensity of the light. After controlling the light on the subject, Rembrandt placed his easel in the center of the studio to choose the point of view. The darkness or tone of the paintings was a choice of the rendering of the scene. (Illustration by Glenn Rand)

We often consider the Renaissance as the height of photorealistic portrait painting. This period brought the use of perspective, light, and shadow to create a dramatic sense of depth and form. Most important from our point of view, the use of light effects in painting was pronounced and continues on today. In addition, the Renaissance painters brought great craft to portraiture, making the quality of the skin important.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) and other Renaissance painters used a concept called “sfumato” that created softness in their portraits. Sfumato comes from the overlay of varnishes and transparent oil paints used to soften the color transitions in facial tones.

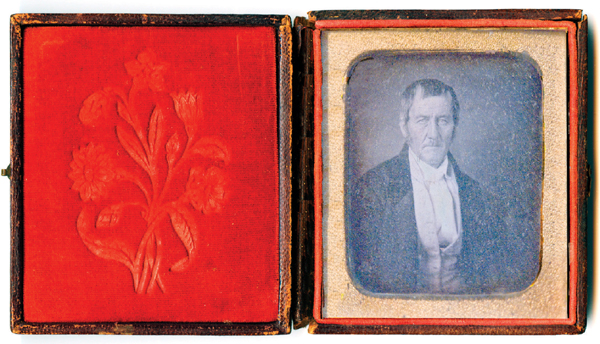

Anonymous daguerreotype in case (From the collection of Glenn Rand)

While highlights and shadows produced a feeling of volume in the paintings, sfumato softened the skin tones to make them appear more natural and pleasant. Today we can see these effects in photography, as some portrait studios have north light windows and often use softboxes to create soft lighting.

There are four major factors in Rembrandt van Rijn’s (1606–1669) paintings that are important in contemporary photographic portraiture. First and most obvious is the lighting, known as “Rembrandt lighting,” which produces a small triangular highlight on the shadow side of the face. The position of the lighting allows for more texture in the image because the light strikes the subject at a shallow angle. Next, Rembrandt often chose a body position that turned the face slightly away from the light source. This is called “broad lighting” in portraiture. Third, while not directly using a backlight, he employed selective background lighting effects to give his portraits both depth and contour. He also vignetted his images to provide more visual centering on the subjects.

Last, in his studio Rembrandt draped a large white cloth across the ceiling and attached it to the top of the prime window used for lighting the subject. This, along with a series of small windows, directed fill light to his subjects, ensuring that the details on the shadow side of the subject were clearly visible.

Another technique from the Renaissance masters is chiaroscuro, which refers to a light-dark contrast that produces volume in the subject. Often confused with Rembrandt lighting, chiaroscuro is an angular light that creates the sense of volume through shadows.

While most people think of portraits as two-dimensional representations, sculptures were often used to represent the likenesses of people. Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680) utilized marble to create portraits. The three-dimensional nature of sculpture brings life to these stable pieces of polished stone.

Technology also became part of painting during the late Renaissance. While optic projections were common knowledge, at this time there is evidence that the camera obscura and mirrors were used to produce the paintings. The use of optical tools for painting can be regarded as a precursor to photography.

In 1839, portraiture changed from the portrayal of reality to the actual capture of reality. In that year, both Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre (1787–1851) and William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877) introduced their processes for photography: the daguerreotype, a mercury/silver amalgam on a polished metal plate; and the calotype (Talbotype), a salt silver paper negative process. After seeing the daguerreotype process, the painter Paul de la Roche (1797–1856) said, “From today, painting is dead.” While he was wrong, parts of the world of painting did change—and none more than portraiture. Portraits that took many hours of sitting and many more hours of painting became much faster and easier with the advent of photography.

At the beginning of photography, the insensitivity of the materials necessitated bright light settings and much longer sitting times than today. In Scotland, the artist David Octavius Hill (an established painter) and Robert Hill Adamson (a camera operator) produced early portraits using the calotype process. At the same time, Albert Southworth and Josiah Hawes licensed and used the daguerreotype process in the United States. These pairs of artist and technician spoke to the complexity of the new photographic processes—the beginnings of a support system to make successful portraits.

Anonymous ambrotype —Mrs. Caldwell (From the collection of Glenn Rand)

In the 1850s, Nadar (Gaspard Félix Tournachon) became one of the big names in portraiture. Part of the reason for notoriety could be because he had his name in large red letters displayed across the front of his studio. Nadar was so popular that other portraitists sought to embellish their reputations by using his name.

Soon, highly sensitized materials reduced exposure times down from 30 minutes with early daguerreotypes to a matter of seconds. With the collodion process, photography took a great leap and introduced a more accessible form for the individual. One of the prominent portraitists who emerged during this time was Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–1879). Her portraits set the standard for moving to a descriptive method that mixed the likeness with emotion captured in the sitter. The story goes that when she took her famous portrait of her friend Sir John Herschel, she asked that he wash his hair but not comb it so that she could portray him the way she envisioned him.

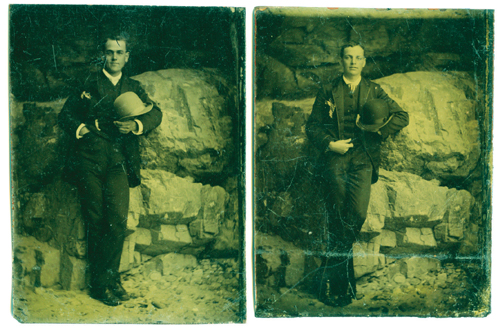

Anonymous tintypes (From the collection of Glenn Rand)

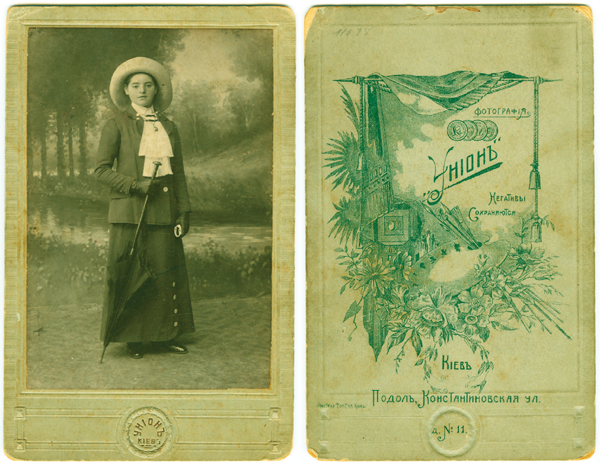

Anonymous cabinet photograph, Jenny Atkins, Kiev, Ukraine, ca. 1900 (From the collection of Glenn Rand)

As the collodion process became prominent, portraitists increased in number. Two practices they employed were widespread: ambrotype-based processes (ambrotypes and tintypes) and card photographs (cartes-de-viste and cabinet cards). Ambrotypes are lightly exposed glass plates that use a black backing to allow silver from the developed negative to reflect the light. The reflected light becomes the highlighted areas of the image, and the black backing becomes the shadows. The ordinary presentation of ambrotypes was the same as daguerreotypes, in small padded cases, which made portraits accessible but still costly.

The less costly tintype ignited a boom of photography. More rugged than an ambrotype, the tintype uses the same concept with the dark surface of the tin functioning as the black backing. Tintypes gained popularity starting at the time of the United States’s Civil War and continued into the early 20th century. There were so many tintype portrait studios that prices went down to a penny an image. These portrait studios for the masses have their counterparts today in school photographers and high-volume portrait outlets with their standard lighting and poses. Cabinet photographs, along with the related cartes-de-viste, were also important to the growth of portrait photography. These were cards and sets of cards made in a studio, which was set up with standard painted backgrounds and props.

Ta-Tamiche, Walapai, 1907 by Edward S. Curtis

(From the collection of Glenn Rand)

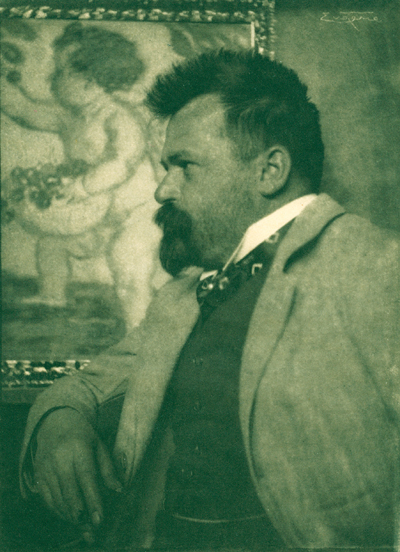

Prof. Adolf Hengeler, 1910 by Frank Eugene (1865–1936)

(From the collection of Glenn Rand)

Also at this time, painters started using photography to aid in their portrayal of the human form and in the creation of portraits. Eugene Delacroix used a photograph of Jean Louis Marie Eugène Durieu to create his famous painting Odalisque. Franz Vin Lenbach had photographers from around Europe make images that he would then convert into painted portraits. In France, Anthony Samuel Adam-Salomon used consistent lighting mimicking the Renaissance that has since been called Rembrandt lighting. Franz Hanfstaengl also began retouching negatives during this period.

As photographic technology progressed, particularly with the introduction of dry plates, photographers were able to move away from the staid portraiture that long exposures required. This also allowed them to leave the confines of the studio and/or the portable darkroom. With this freedom came both an expansion of the settings for portraits and wider approaches to using portraiture. While Matthew Brady (1823–1896) had a studio, many of his most powerful portraits were made on the battlefield. At the beginning of the 20th century, Edward S. Curtis (1868–1952) and August Sander (1876–1964) used their portrait skills to produce ethnographic studies. Curtis traveled throughout the United States, producing many portraits of Native Americans along with other documentary images. Sander left his portrait studio to document the people of Westerwald, near Cologne, Germany. He used the same skills and approaches from his portrait studio for this project that he continued through the rest of his working life. In the 1960s and 1970s, Irving Penn (1917–2009) traveled around the world with a translucent white tent, creating a portable studio to make his ethnographic portraits that became “Worlds in a Small Room.” The work of these photographers and many others expanded the vernacular as well as the applications of portraiture.

From the advent of photography, “learned” societies and professional organizations were established that became important to the development of portraiture. Among them are the Royal Photographic Society (1853), the Professional Photographers of America (PPA, 1880), and more recently, the BFF, or Bund Freischaffender Foto-Designer (German Professional Photography Association, 1969). These groups and others, such as today’s Wedding and Portrait Photographers International (WPPI), the Society for Wedding and Portrait Photographers (SWPP), and Arbeitskreis Porträt Photograhie International (APPI), offer conferences and educational workshops that establish standards, share styles, debate aesthetics, and bestow certifications. Many nonmembers mimic the styles from practitioners within these societies.

As photography matured in both technology and aesthetics, portraiture changed as well. One trend that emerged in the late 19th century was pictorialism. This photographic movement was fathered by individuals who left the formal societies to form the Brotherhood of the Linked Ring and later the Photo-Secession. These groups attracted some of the luminaries of photography, including Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946), Edward Steichen (1879–1973), and Clarence White (1871–1925). A critical attitude toward soft, romantic, and impressionistic photographs permeated this movement, with portraits returning to the dark, tightly focused images reminiscent of earlier times in portraiture. Through publications such as Camera Work, portraits were given an equal footing with other photographic art. The effect was to give photographers more freedom to approach portraiture, which resulted in changes to settings, lighting, and the overall approach to the subjects. A prime example is Edward Weston (1886–1958), who originally had a studio but who made many of his iconic portraits in natural light from angles that challenged traditional approaches to the portrait.

Three photographers, who were active well into the 20th century, had a great impact on the direction of portraiture. First was Sir Cecil Beaton (1904–1980), who became the portraitist to British royals and celebrities. He moved away from the studio into the environments of his subjects. While he worked in a sitter’s environment, for the most part he used formal poses. Beaton moved with the developing technologies, adopting the latest photographic tools available to him.

The second of these three major portraitists was Yousuf Karsh (1908–2002). Karsh moved to Ottawa, Canada, and opened a studio there. Though known for his studio portraits, he also produced photographs on location. One of his most famous images is of Sir Winston Churchill in his wartime office. Karsh used a specific lighting ratio that became part of his style. Throughout his career, he was known for his large-format (8 x 10 inch) black-and-white photographs.

The last of the three great mid-century portraitists was Arnold Newman (1918–2006). Starting in the 1960s, he became known for environmental portraiture. While he produced many of his images outside the studio, he did not accept the environment as it existed. Instead, he rearranged objects and lighting to produce an image that dealt with the sitter’s persona as well as their likeness.

© Judy Host (Courtesy of the artist)

A prime example is his portrait of Alfried Krupp for LIFE magazine. Through his use of lighting, Newman communicated his feelings about Krupp, a Nazi arms manufacturer.

Crossing this period was the work of George Hurrell (1904–1992). Hurrell went to work in Hollywood and made photographs of movie stars. He used specular lighting, chiaroscuro, and tenebrism (strong spot lighting) to create a “heroic” style, the opposite of the more natural approach of Karsh. Hurrell and other celebrity portraitists had a great deal of impact on how portraiture grew visually.

Several schools opened to train photographers that featured strong portrait course work, including Brooks Institute and Rochester Institute of Technology. However, education was not the sole purview of institutions of higher education; for example, the PPA’s Winona School of Photography offered courses by luminaries such as Joe Zeltsman. Other established photographers, like Monte Zucker, Frank Cricchio, and William McIntosh, shared their ideas about posing, lighting, and running a profitable business through workshops and conferences. Zeltsman promoted a set of standards for posing and Cricchio advanced the ways portraitists approached their lighting, while McIntosh was well known for his business practices and elaborate formal location portraiture.

During the latter part of the 20th century in the United States, many working professional portraitists affected the look of the field. Philip Charis incorporated the styles of Rembrandt, John Singer Sargent, and Sir Joshua Reynolds. Leon Kennamer moved his portraiture out of the studio and into natural settings, combining the use of natural light with the use of light shapers. Joyce Wilson rejected the staid regulations of the formal photographic societies to personalize her approach, making portraits that she saw as artistic rather than formulaic.

In this portrait, the use of the inserted face in the upper-right corner balances the image through similarity of form to add visual weight and interest to the right side of the image, opposing the dramatic arm positions of the subject at the left third

© Arthur Rainville (Courtesy of the artist)

© Julia Sparks Andrada (Courtesy of the artist)

The sharing of images through publishing has been important to the development of portrait photography. Magazines like Professional Photographer and Rangefinder in the United States and Professional Imagemaker in Europe have brought images to large numbers of photographers and have encouraged the sharing of style and technique.

Today we find that portrait painters borrow from the world of photographic arts. The makeup ideas of commercial photographers such as Douglas Dubler and the posing concepts of Annie Liebovitz drive some contemporary approaches to portraiture. Furthermore, the art world is absorbing diverse approaches to portraiture, as seen in the projects of Bettina Flitner. As Joyce Wilson said of the history of photographic portraiture, “There will always be something new.”

Yojhi Yamamoto © Elinor Carucci (Courtesy of the artist)

Styles

The history of portrait photography is a good starting point to view the ways in which these images are used. Roughly speaking, there are two approaches utilized in choosing to make portraits: for commercial purposes and for fine art. Beyond the issue of reliably getting paid for a portrait, the only difference between commercial and fine art portraiture is whether the portrait is made for the client or for self-assignment. Beyond that distinction, all the tools, controls, and approaches are the same.

While the photographer controls both formal and informal portraits, a candid portrait is an image that is not captured in a deliberate way. While the intent of a candid portrait is the same as other portraits—to capture a likeness of the subject—the method is about photographing the subject naturally without any posing, styling, or adjusting of the setting. This usually means that artificial lighting (other than on-camera flash) is not used and that the photographer, in effect, “steals” a moment of the subject’s life.

Alexey Brodovitch © Benedict J. Fernandez (Courtesy of the artist)

Art Buckwald in Paris, 1961 © Douglas Kirkland (Courtesy of the artist)

An environmental portrait differs from a candid portrait in that the photographer controls both the subject and environment. The environmental portraitist selects the setting for the portrait as well as controlling posing, lighting, and styling of the image. The concern with an environmental portrait is as much with the setting as with the subject, because the intent is to use the location to enhance the viewer’s understanding of the subject.

Ethnographic portraiture is about the subject’s cultural, national, or ethnic identity. These portraits may rely on any approach, but the end result is more about the circumstances of the subject’s life than their likeness. For these reasons, the subject’s attire can be a very important element in the portrait.

To a certain extent, both commercial and fine art portraiture are without differences. A publication might use a portrait by Douglas Kirkland for commercial purposes, and the same portraits in a gallery might be viewed primarily as fine art. Depending on the end use, commercial and fine art applications may wish to use any type or style of portrait. This is a good point to close this brief overview of photographic portraiture. In the end, portraits are always about the subjects, their likenesses, their personalities, and their lives.

Tuareg Bilal © Douglas Dubler (Courtesy of the artist)