Chapter22

Shipping

INTRODUCTION

When you envisioned yourself working in this industry, I bet not one of you started with a vision of yourself spending months on end (from early morning until late at night), typing pro-forma shipping invoices (especially as you probably don’t even know what they are — yet) and then going home and dreaming about typing them all night long, figuring out how to best get equipment over an international border while dealing with unscrupulous customs brokers, trying to guess how many LD-3s you’re going to need to wrap your show, racing the clock to get a key prop or several boxes of raw stock to location before shooting begins for the day, discovering how to ship a cougar to Panama or a water buffalo to Hawaii. Shipping is just one of those things we find ourselves involved with that no one ever warned us about or offered us a class on how to do well. Although it may not be the most exciting part of the business, it’s one of the most necessary, because when handled poorly, it can slow down a production, if not bring it to a total halt.

This is another chapter I could write an entire book on. You wouldn’t think that shipping is a big deal, but take it from one who’s been there and done it — it is! What’s most amazing is that shipping always takes more time and costs more money than anyone thinks it should. Few people realize just how much detailed planning and organization is required to insure that absolutely nothing is held up because a shipment didn’t arrive on time. And as in any other facet of production, when it comes to shipping, planning saves money.

If you plan to do a show away from your base of operations — whether it’s in another state or province within the same country or another country, and you’re planning on shipping any manner of equipment, materials, supplies, set pieces, vehicles, aircraft or animals — pay attention, because this chapter is going to help you a lot.

SHIPPING COMPANIES

The first thing you need to do is to find a company that specializes in shipping for the entertainment industry. Don’t choose an all-purpose shipping company just because your Uncle Karl happens to works there. Stick with one that specializes in our business, because they know how we work, what we expect, have all the necessary international contacts and are familiar with the types of things we ship. You might want to talk to two or three of these niche companies — get a feel for how they operate, what they would charge and how they would specifically handle your show. Also check references and talk to others who have used their services.

These companies are technically freight forwarders and will first and foremost advise you as to the most effective way to ship your goods. As your shipper of record, they’ll help you consolidate, prepare and arrange for all your shipments. If you’re shooting out of the country and need a customs broker, they’ll make arrangements for that, too. And they’ll almost always be able to provide you with door-to-door service. Charges will be based upon destination, the mode of transportation selected and any additional services needed. Shipping company reps will give you an estimate of costs based on the volume you anticipate shipping. Once you’ve selected a company, they’ll also file claims with the various carriers on your behalf if any of your cargo is damaged during the shipping process.

Once a company becomes your shipper, they’ll not only be acting in your best interest and on your behalf with the appropriate air, ground and ocean carriers, but they’ll be paying those carriers as well as retaining the services of and paying customs brokers, the drivers who make the pickups and deliveries, the haz-mat packers, etc. (as needed) for handling your shipments. So when they send you an invoice, understand that they’ve already paid for the services they’re now charging you for. Stay aware of what you’re being charged for and understand that those fees will quickly multiply if there’s an increase in the number of shipments originally predicted, if loads are heavier or take up more volume than anticipated or if shipments became more complicated than expected. If your shipping rep is doing his or her job properly, you’ll be informed of certain overages as they arise and often given the opportunity to make alternate choices. What’s not okay is for production companies to decide that because they’ve gone over their shipping budget, that they’re not going to pay their shipping company all that they owe, because they feel that the bills are too high. It’s not fair to the company that’s already laid out the funds to make sure that your shipments got through and nothing was held up. The time to dispute costs is before shipments are made — not after. Shipping can be expensive, costs add up fast, and they can easily get out of control if someone isn’t staying on top of them and working closely with the shipping rep.

SHIPPING COORDINATION

Just as with travel-heavy shows using a dedicated travel coordinator, shows that entail a good amount of shipping commonly hire a dedicated shipping coordinator. Otherwise, the shipping chores are usually added on to the production coordinator and/or assistant coordinator’s already very full plates.

Whether it’s a shipping coordinator or production coordinator, one person should be the shipping contact for your production, and no one individual or department should be allowed to make their own shipping arrangements. Neither should anyone be allowed to place orders to be shipped directly by vendors without prior approval. You don’t want to lose control over your ability to:

• Consolidate shipments

• Utilize the most cost-effective means of shipping

• Buy the same materials and supplies locally that crew members will inadvertently order directly from their vendors back home because it’s easier, they’re busy, used to doing it that way and their mind isn’t on your shipping budget.

Once individuals, departments and vendors are allowed to make their own shipping arrangements (without prior approval), you lose control of your costs. I see it happen all the time, and the waste of money is maddening. On one show I was on, a make-up vendor Fed-Exed a large case of facial tissue to us on location — facial tissue! — a product we could have bought in any quantity at the local Costco. I thought that was pretty outrageous until I heard of two other shows — one in which two shipments of donuts were shipped from New York to London, and another where carrot juice was shipped from New York to the Dominican Republic every day for two weeks. I know we’re used to the comforts of home, but only you can decide at what price. Besides, I can’t believe that donuts don’t exist in London.

GENERAL SHIPPING GUIDELINES

• Don’t wait until the last minute to make your shipping arrangements, or you’ll lose options and increase your costs. It’s often necessary to start planning months in advance (to be able to book space, meet shipping schedules, obtain necessary permits, etc.) and to get the crew on board for what they can (and can’t) bring, how it all needs to be packed, manifested and labeled. When I was working on Tropic Thunder, we shot on Kauai. That required transporting our vehicles and much of our gear via ocean, but the ships only went as far as Honolulu, and from there, everything came the rest of the way via barge. So we were subject to both Matson’s Long Beach to Honolulu schedules and to the inter-island barge schedules. And it wouldn’t have been so bad if all we had had to worry about were the schedules, but when it came to the barges, we also had to worry about space availability. So last-minute arrangements were always hit-and-miss, and it often took some degree of pleading, praying and the calling in of a favor or two to get space on an already fully booked barge. Sometimes, no matter what we’d try, we’d just have to wait for the space to become available.

• Generate a daily or weekly shipping schedule, so everyone who needs to know, is kept informed as to what’s going out and coming in (to and from each location) on a daily basis. Include any specific instructions, as well as a general description of the shipment, pickup times, mode of transportation, arrival dates and times, flight numbers, way bill numbers, container numbers, manifest numbers — any reference that will make shipments easier to track and find.

• Consolidate your shipments as much as possible. Sounds like an easy thing to do, but it’s not. I always start by asking crew members to try to anticipate everything they’re going to need to ship to location, so we can ship it all — or as much as possible — at one time. Of course, there are specific rentals that have to be taken into consideration — weighing the cost of shipping a piece of equipment before it’s needed (thus possibly incurring additional rental fees) opposed to the added cost of shipping it separately later. But there are costs associated with each shipment (no matter the size of the load or how it’s being sent), and just in general — the fewer the boxes/containers/pallets/loads/ pickups/deliveries/border crossings, etc. — the lower your shipping costs will be. The thing is, though, that it seems that after the big stuff arrives on location, and you think you’ve got it all, there continues to be an endless stream of smaller (and some not so small) add-ons, exchanges, last-minute orders and expendables flowing in on almost a daily basis. Once on location, events always arise that create a need for something that someone can’t live without. And it’s those constant smaller shipments that are so difficult to control and add so much to your shipping budget. So try to anticipate your needs in advance and consolidate as much as possible.

• Buy and/or rent as much as you can locally once you’re on location. Even if an item is more expensive on location than it would be at home, you’ve got to weigh the cost of shipping it there. Also take into consideration the tax incentive or rebate being offered where you’re shooting, because in most states, the greater the local spend, the sweeter the incentive or rebate. It’s amazes me that there are so many people who, once taken away from their home base, act as if they’ve been transported to the moon. As many times as I explained that there’s a Costco in Tijuana where we can get laundry detergent (the same kind we buy at home), and that there’s a beauty supply vendor in Hawaii where we can buy makeup products, it was tough getting it to sink in. The prevailing attitude is that it’s just easier to bring everything from home. But it isn’t usually cost-effective, so strict guidelines and good communication skills are essential to win this battle.

• I appreciate FedEx, UPS and DHL and have rarely ever been on a show that didn’t have at least one account with one of these shipping carriers. But some people use these companies just out of habit, and because it’s easy — even when there are other (sometimes, less expensive) options. So if you’re using a shipping company to pouch or send other things to your distant or foreign location, consider consolidating items that you’d instinctively ship via FedEx (or one of the other carriers) with other items already being shipped, especially when it comes to heavy boxes and crates and large items — it’s often more cost-effective to send these things through the production’s shipper. But if you’re not sure, consider your options and compare prices.

• Don’t declare an overnight shipping emergency unless there truly is one. You don’t want to cut any shipment too tight and take the chance of something not arriving in time, but be realistic about arrival times. Sending things on a rush basis all the time could get pretty pricey — especially when it’s not necessary.

• Just as important as it is to have someone oversee the shipping going to location, it’s just as important to have someone on the other end responsible for logging in each shipment that arrives and making sure it gets to where and to whom its intended in the least amount of time. On very large shows, this could be a full-time job in itself.

• Urge crew members to let you know if they’re expecting a package, and what to do with it when it arrives (have it delivered right to the set, leave it in the office for pickup or have it taken to the hotel or elsewhere). I can’t tell you how many deliveries arrive with no instructions — sometimes without even a name on the box.

• Send your crew a memo outlining your shipping guidelines, so they have all the information they need and there’s no question as to what you expect from them. Provide information on the containers that will be made available to them, how to pack and label, how to prepare a manifest, what to do with dangerous goods, what to do with personal belongings, etc. Include appropriate schedules and indicate the date that their gear has to be ready for pickup.

Dangerours Goods

Dangerous (or hazardous) goods encompass anything potentially explosive, flammable, toxic or corrosive — items that have been deemed capable of posing a significant risk to health, safety or property when transported. It’s not just pyrotechnics, paint thinners and solvents that qualify as dangerous, but also many hair and make-up supplies (even Evian mineral water spray), the canned air the camera department uses, batteries, WD-40®, etc. It’s essential that you talk to your shipping rep about transporting anything that might be classified as dangerous (or hazardous) goods, because they’ll need to be handled, packed and labeled very differently — by someone certified to handle and pack haz-mat materials. Some freight forwarders have their own in-house packing departments, but if yours doesn’t, they’ll make the arrangements for you. Before anything can happen, though, you’ll need to get copies of the Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) from the manufacturer of each of these products you wish to transport.

The shipment of hazardous materials is restricted and may be prohibited depending on the quantities you want to ship. It all has to do with the type of haz-mat material and the volume allowed within a specified space. And when transported by air, certain types of dangerous materials may be flown on passenger planes (in certain quantities) but others may be transported only by cargo plane. It’s a violation of U.S. law to ship cargo containing dangerous goods that haven’t been properly declared, identified and packaged, and severe consequences are imposed for doing so — not to mention that you’d be jeopardizing your entire shipment.

Here’s a list of examples of some common hazardous materials found on productions:

• Household products such as hair spray, glass cleaner, etc.

• Aerosol cans

• Furniture polish

• Paint thinner

• Solvents

• Cleaners

• Flammable liquids

• Isopropyl alcohol

• Compressed gas cylinders

• Paints

• Dyes

• Certain special effects

• Lubricating oil

• Mineral oil

Be sure to allow more lead time for the special handling of these materials. And chalk up another reason to buy locally if at all possible. Haz-mat materials require additional arrangements, handling, time and cost, so anything that can be purchased on location should be.

Modes of Transportation

Depending on your destination, there are three basic modes of transportation: ground, air and ocean. Rail is used occasionally, but as it takes longer (nine days across country), it’s best used when wrapping a show and shipping back assets (production-owned set dressing, props and wardrobe) — nothing that you’d be anxious to get off of rental. You probably wouldn’t ship anything less than a full container by rail, but if the time frame works for you, shipping this way would be more cost-effective than shipping by ground.

Ground

Not many freight forwarders have their own fleet of trucks and trailers, but when shipping via ground is in order, they’ll contract with a carrier to pick up and deliver your materials, equipment, set dressing, etc. Truck loads are classified as FTL (full truck load), also known as a dedicated load or LTL (less than a truck load). And when you have less than a truck load, your goods are consolidated with others. It’s a less expensive method of shipping, but slower as well.

Air

There are flights that carry passengers and cargo, but if you have a lot to ship, you can’t always guarantee the amount of space available for cargo or that what you’re sending won’t get bumped along the way. And then there are cargo-only flights, which are always your best bets. It’s also wise to ship your goods on nonstop flights if at all possible to avoid the chance of your shipment getting bumped.

Air cargo is priced by the actual weight or volume, whichever is greater, so you’ll always be asked for the dimensions and weight of anything you’re shipping. The following is the formula for determining volume:

If you have several loose boxes, it’s always best to palletize — place them on a pallet and shrink-wrap the load. If you’re not able to do this, your shipping rep will have it done for you, because at the least, you’ll need a pallet jack to lift and move the freight.

Equipment is usually packed into shipping containers — the most commonly used in our industry is the LD-3, which is 61.5" long × 60.4" wide × 64" high and can hold about 3,000 pounds. E containers are commonly used for wardrobe, and they’re 42" long × 29 wide × 27" high and can hold about 300 pounds.

One of the most important things to be aware of when it comes to shipping by air are the airlines’ cutoff times — the latest you can get something to the airport for a specific flight. Here are some the general guidelines:

• Domestic Cargo: two (2) hours prior to any flight and two (2) hours once the flight has landed to recover your shipment.

• Counter-to-Counter service: one (1) hour prior to any flight and one (1) hour once the flight has landed to recover your shipment.

• International Airfreight: three (3) hours prior to any flight and four (4) hours once the flight has landed to recover your shipment.

• International Airfreight: three (3) hours prior to any flight and four (4) hours once the flight has landed to recover your shipment.

• International Express Cargo: two (2) hours prior to any flight and two (2) hours once the flight has landed to recover your shipment.

Ocean

There are a number of ocean carriers that will transport containerized freight and vehicles via their shipping lines, and your shipping company rep will know the best one to use for your show and needs.

When you’re planning on shipping via ocean, it’s vital to book space sometimes months in advance, just to ensure that everything will arrive on location before it’s needed.

Vehicles being shipped via ocean are classified as rolling stock. And for each vehicle (car, truck trailer, etc.) you plan to transport within the U.S., you have to provide:

• A description of the vehicle (year/make/model)

• The dimensions of the vehicle

• The license number

• The VIN number

• The value

• The weight

• A copy of the title and registration

• A letter from the registered owner granting the production permission to be shipping their vehicle(s)

When shipping internationally, you have to provide the original title to the vehicle to Customs three days prior to shipping.

Like truck loads, ocean containers are classified as FCL — full container loads, or LCL — less than container loads. And once again, less than a full load means that your goods will be consolidated with others. It’s less expensive but could take longer to claim once the ship arrives in port — especially if your things were placed toward the front of the container, and you have to wait until everyone else claims their goods before yours will even see the light of day.

For materials, equipment, props, set dressing, wardrobe, etc. that will be shipped in containers, the shipping lines will release containers (and chassis for them to sit on) free of charge for a period of 24–48 hours in advance for loading. And they’ll give you another 24–48 hours once your shipment has been claimed for unloading. If you take more than the allotted time to load or unload, you’ll be charged a daily rental for use of the containers and chassis until they’re consigned or returned to the shipper (and this could get pricey). If you want to keep the containers longer, or even use them for storage or to work out of while on location, then you might want to think about buying used containers that you can load, ship, use, then sell once you’re back. This is often a more cost-effective option than paying rent on someone else’s container. I know department heads who own their own containers for just this purpose. Keep in mind, though, that when you use containers owned by members of your crew, they have to be inspected by a container surveyor to make sure they’re seaworthy before they can be used.

Your shipping rep will make arrangements to have the containers picked up and delivered to wherever the containers are going to be loaded. Arrangements will also be made to have the containers and chassis picked up on a specified day and time and transported to the port. Once they arrive on location, they can be picked up at the port, or your shipping rep will make arrangements to have them delivered to a designated location.

Should you be asked to have a container dropped off without the chassis or pick up or move a container that isn’t sitting on a chassis, you’ll need a crane to load, unload and/or move the container.

If you want to ship picture cars or small vehicles (motorcycles, golf carts, dune buggies, etc.) inside of a container, make sure that they contain no gasoline and the batteries are disconnected. If any of them (a motorcycle, for example) is registered, then you have to present your shipping rep with the same documentation as listed earlier.

The most common size of containers are the 20-and 40-footers, and you can get ones that are refrigerated — something your caterer might appreciate. Ocean carriers also supply 20-foot and 40-foot flatracks, which are open on both sides and an ideal way to ship lumber. I’ve also used them to transport helicopter parts and certain odd-shaped pieces of equipment.

When loading a container, make sure that there’s a pathway down the middle of it, so if selected for inspection, everything inside can be easily accessed. Note the container’s ID number, so it can be tracked, and purchase a combination lock for the container’s doors.

Start the process early by asking each department head how much container space they anticipate needing (circumstances may change later on, but start with a good guess). Some departments will utilize a number of containers on their own; others will share space with other departments. Also confer with your transportation coordinator as to the number and types of vehicles that are being considered for transport. Only once you assemble a fairly accurate list of how many pieces of rolling stock and how many containers and flatracks you’re likely to need will your shipping rep will be able to supply you with costs and options.

Maximum weights for all containers and flatracks (including the container and chassis) are approximately 40,000 pounds because of the legal weight allowed on U.S. roads.

DOMESTIC SHIPPING

Manifests

Manifests (a list of the items being shipped) aren’t generally as detailed when shipping items within the United States as they are for international shipments, but for insurance purposes, it’s still necessary to keep track of what’s being shipped. Should there be a claim for items that are lost or damaged, you’re going to want to have a record trail. Check with both your insurance and shipping reps to find out what each requires.

Most shipping companies don’t require manifests to move domestic loads, but you still need to let them know what you’re sending, and that can be done via an e-mail. You can be as general as “Truck #1 will be carrying camera equipment and Truck #2 will be carrying grip and electric equipment.” For individual boxes and crates, they’ll also require dimensions and weights (unless you have a scale, the weight part is something you’ll just have to guess at).

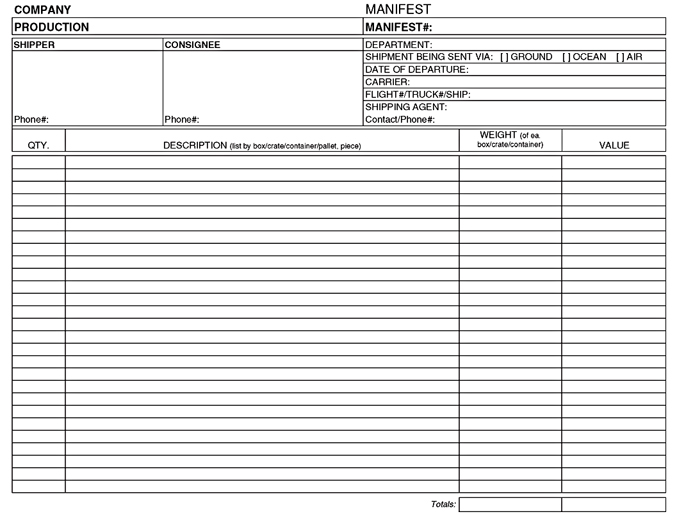

My preference is to play it safe and manifest all boxes/crates/containers being shipped, and you’ll find a copy of my manifest form at the end of the chapter. If you want to create one of your own, it should include:

• The shipper (where the shipment is originating from)

• The consignee (indicate the name of the show and where the shipment is going)

• Number of pieces in your shipment

• Quantity, description and value of items being sent

• Weight of each box, crate or container (if you can provide it)

You can combine descriptions when describing like items. For example, if you’re manifesting a crate full of tools, you can list “20 assorted hand tools” without having to indicate each piece individually, or “50 pairs of men’s pants” without having to list the sizes, colors and styles of each. Certain kits or packages can also be listed as such without having to describe each piece contained within the kit or package.

If you’re having any materials, supplies, equipment, props, wardrobe, etc. picked up directly from a vendor, inform the vendor that you’ll need a manifest. You’ll also need to supply the shipping company with the vendor’s address, phone number, a contact person, business hours, the time the shipment will be ready for pickup and any special instructions that might be necessary.

Be aware that even domestic shipments are subject to inspection.

Packing and Labeling

All boxes and crates should be labeled with the name of the show, the department it’s going to and a contact name and number. If there’s more than one box or crate — three, for example — label them, Box 1 of 3, Box 2 of 3 and Box 3 of 3. Boxes occasionally get separated or arrive without enough information as to what they contain or whom they’re for, so the more complete they’re labeled, the faster they’ll arrive. Advise your vendors (who may be shipping supplies directly to you on location) to label their boxes properly, with the name of who it’s going to and the applicable department clearly noted.

Shipping Dailies

While on location, if you’re shooting on film, you’ll be shipping the film shot each day to the lab each night (except Friday and Saturday’s film, which is sent out on Saturday evening or Sunday). The film negative is developed during the night, the sound is synced to picture the next morning and dailies (made from the director’s selected takes) are shipped back to location the next day in the form of a work print or DVD and sometimes on a hard drive. On some pictures, the film only goes one way — from location to the lab, and then the dailies are uploaded or streamed back to location (instead of shipped).

Unless close enough to have the film driven in each night, most productions will ship their film via counter-tocounter air service. This is something your shipping rep can handle for you. There are also courier services that specialize in the handling of dailies, or you can set up the routing and shipping of dailies on your own. If you’re going to do it on your own, though, be aware that it needs to be set up at least eight days prior to your first shipment — the minimum amount of time it takes to become a “known shipper” with a commercial air carrier. This is a TSA requirement, and you can get set up through your airline rep or designated shipping company.

Handling it on your own, you would start the process by opening an account with the air cargo division of the airline. Select an airline that flies nonstop to your destination, with the most evening flights. If it’s impossible to get a nonstop flight, choose a route that has as few stops as possible. This will lessen the chances of the film being unloaded at the wrong stop.

If you call the airline, a representative may come to your office to open an account or will e-mail you a credit application to fill out and send back. After that, someone from the airline or shipping company will come by to set you up as a known shipper. The airline rep will then send you preprinted way bills (with your company name and account number on them) and flight schedules. Keep the flight schedules of more than the one airline in case flights are canceled or an unscheduled rush situation on your end necessitates the use of another carrier. Depending on how many different airlines you might use, it’s a good idea to open accounts (and become known shippers) with at least two of them. Unfortunately, gone are the days when you could use a carrier you don’t have an account with by paying cash at the counter.

Be sure to keep a copy of each way bill in case your shipment is delayed, mislaid or lost. (They also provide backup to the shipping bills.) Also keep a log of every shipment that leaves the production office, indicating: date, waybill number, flight number, arrival and departure times and the contents of your shipment — the number of reels you’re shipping, number of sound tapes (DATs) or DVDs, still film, any equipment you may be returning, etc. (See the Dailies Shipment Log form at the end of this chapter.)

A production assistant from your home base office or a courier service will pick up your daily shipment each night. If it’s a PA, he or she should go to the airport before you start shipping dailies and introduce him/herself to the airline personnel who will be handling the film shipment when it comes in each night. (Consider having the PA take a few show T-shirts along as introduction gifts.) Should there be a problem with the flight or the routing of the dailies, it helps to know the airport routine and to be on good terms with the airline staff.

Once the film starts arriving, your PA or courier will open the box(es) and separate the film for the lab, the sound tapes/DVDs, the still film, the envelope(s) for the office (you should pouch copies of all your daily paperwork back to the home office via the daily shipment each night), and whatever else you’ve sent. The PA will drop the film and sound off that night, and deliver the remainder to the office first thing the next morning for distribution.

Labels on the box(es) should be addressed to the production office (always include the office phone number), with the notation HOLD FOR PICKUP. Boxes should also indicate or have labels that clearly and prominently read UNDEVELOPED FILM — DO NOT X-RAY. I’ve also seen some that read: UNDEVELOPED FILM — PROTECT FROM RADIOACTIVE MATERIALS AND X-RAYS.

You can use regular cardboard boxes or the cases that are specifically made to hold and ship 1,000-foot film cans. And if not out already, there’s talk of new (more distinctive) airline-approved stickers and lead-lined pouches and boxes, which would be great, because as many DO NOT X-RAY stickers as you may plaster your boxes with, there are still those rare occasions when some cargo handler at some airport stops paying attention to what he’s doing and will run boxes of exposed film through X-ray (Big ouch! Big insurance claim! Big problem!).

It’s best to ship film on the same flight each evening. Taking the lab’s cut-off time into consideration as well as the time needed to transport the film to the lab, pick the latest flight available in order to get the film there on time. If it works for you, the last flight out is the one usually selected to allow a full day’s worth of shooting (or most of one) to be sent out. If shooting for the day isn’t completed by the time the driver has to leave for the airport, the camera crew will have to “break film” at a designated time and send in what they have.

If you have your own airline cargo account, the driver making the airport run should have the packed boxes, a completed way bill and a memo indicating the flight information and a description of what’s in each of the boxes you’re sending. He or she should call the production coordinator from the airport to confirm that the boxes got on-board and that the flight was on schedule. If there’s a problem, a subsequent call should be made to inform Production that the boxes had to be sent on another airline or that the flight is going to be delayed. The production coordinator will in turn call or e-mail the PA or courier service on the other end to confirm an estimated arrival time and to give them the way bill number. When the driver returns, he or she should give the production coordinator a completed copy of the way bill. Because most labs are closed from Friday night to Sunday night, the footage from Friday and Saturday is shipped on Saturday evening or Sunday afternoon, so that it arrives before midnight on Sunday.

Weapons, Ammunition, and Explosives

When you’re shipping weapons domestically, clearly label the boxes and crates MOVIE PROPS. Don’t write anything on the box that would indicate that guns are enclosed, but be sure to let your shipping rep know what’s being sent. (For shipping weapons internationally, you’ll find the information later in the chapter.) Blanks are a different matter, though, and are classified as dangerous goods. They therefore need to be handled and packed by a certified haz-mat shipper and shipped separately. The same would hold true for explosives.

Shipping Animals

I’ve had the distinct experience of having shipped a cougar named Satchimo, two water buffalos — Bertha and her baby, Little Jack — and a water monitor lizard whose name escapes me at the moment. And what I can tell you is that it takes a lot of planning to ship animals, whether it’s across the country or across a border. Start by talking to your shipping rep and the company you’re getting your animals from. A lot will depend on the animal (or animals), where they’re being shipped from and to and how they’re being transported. Do your homework:

• Start by checking the regulations for bringing animals into the specific state or country where you’ll be filming. Are there quarantine procedures? Will you need to fill out an application, obtain a permit and/or post a bond? Are there restrictions on certain types of animals — reptiles, for example? Each jurisdiction has its own regulations, and getting everything sorted out and approved could take months, and often does.

• Regulations pertaining to the safety, care, handling and the import and export of animals fall under several agencies — U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services, the Department of Agriculture, the Department of Animal Care and Control and the American Humane Association’s Film & TV Unit. Your local film commissioner should be able to advise you on local guidelines and provide you with necessary contacts, and your shipping rep should be up to date on the full array of guidelines. Much will depend on the type of animal(s) you plan to ship, where you need to ship it/them to and the requirements associated with each.

• Most owners of the animals you’ll be using will require that you obtain mortality insurance on the animal, so make sure that coverage is secured before transporting.

• When transporting an animal any significant distance, air travel is the most humane and expedient method of transportation. Your shipper will know which air carriers transport animals and should be able to make arrangements for at least one animal handler to accompany the animal.

• To obtain mandatory insurance, permits and sometimes certificates, a veterinary certificate is required on each of the animals before shipping. The vet must also submit a Letter of Acclimation, which specifies the temperature range the animal is acclimated to. The shipper needs to be aware of temperatures that are either too high or too low for the animal’s comfort — not only during transit, but also between connections, so proper arrangements can be made to keep the animal comfortable.

• Be aware that during the summer and winter months, some airlines place embargos on shipping certain types of animals because of extreme temperatures.

• Make sure arrangements are made for the proper ground transportation to and from airports (such as a horse trailer).

• Most animals are kept in a cage or crate during travel, so get the maximum dimensions the aircraft can accommodate, what their crate requirements consist of and make sure any specific crate is both a safe and comfortable size for the animal. When flying Satchimo (the cougar) to Panama, the airline gave us the dimensions for a crate we had to have made — one that would fit in the hold of the aircraft. Turns out, though, that no one thought to consider the dimensions of the door, and come the night of departure, it was impossible to get the crate into the plane. So the crate had to be remade, and we had to ship Satchimo the next night. The morale of this story is two-fold — make sure you can get the animal’s cage or crate through the door of the aircraft (or aircrafts, if you have connecting flights), and always plan to ship the animal a few to several days before you need it to work. When it comes to scheduling, make sure to build in a reasonable buffer should there be a holdup during transport or in getting through quarantine. Getting there early also gives the animal a chance to acclimate to the new location.

Returns

Once you arrive on location, returns start occurring almost immediately and include equipment you’re finished using (and want to get off of rental), items that arrived but were the wrong size or model and items that arrived defective and need to be replaced. The returns trickle out until it gets close to wrap, and then everyone wants their gear sent out right away — to get it off of rental, to send to the next location or to possibly use on another show. Sometimes everything has to go quickly, because it’s a matter of having to clear the premises. Once again, the shipping or production coordinator goes into overdrive to get everything shipped (back) in a timely (and hopefully) cost-effective manner.

Before you start shipping anything, though, decide what can stay. Usually nonhero (non-essential) assets purchased for the show that won’t be needed for additional photography or reshoots can be sold — like office furniture you bought locally, possibly some props or background wardrobe. Don’t spend the money to ship back anything you don’t have to.

I was on location a couple of years ago and walked into the production office one morning to find a box sitting on the floor in front of my desk with a note on it written by crew member that read “Please FedEx.” First of all, I make it a habit of never shipping anything unless I know what it is. The crew member should have sent an e-mail requesting the return shipment and explaining what he wanted to ship. He should have also known that the person in charge of shipping is the only one who gets to dictate what gets shipped and how. So here are some suggestions from someone who’s been there and done that:

• Either send out a memo or go talk to someone from each department to find out what their shipping needs are going to be, such as: when will their containers be packed and ready to be picked up, how many LD3s will they need, how many E containers? You need this information to insure that you have enough time to reserve ample cargo space.

• Order a generous supply of packing supplies — boxes, packing paper, bubble wrap, tape, labels, etc. — and let the crew know when you have it.

• If everyone is going to be loading at once, find an area where you can have containers or trailers dropped off and left for one to three days while being loaded. You’ll want to create a record of each container or trailer number, the department it’s assigned to and a description of the contents. (Once again, your insurance carrier might require a detailed manifest and an estimated value of the contents to cover losses that might occur during shipping. Keep in mind that if you’re loading the exact same items you sent to location to begin with, you can use your original manifests.)

• When filming has been completed, there are companies that will pick up your remaining haz-mat materials for proper disposal. Hopefully you won’t need to ship any back, but if you do, you’ll have to go through the same process of having these products packed by a certified haz-mat guy. Your shipping rep will help you with either, but contact him or her as soon as you can collect the information from your department heads as to the remaining amounts of dangerous goods they each have.

• You’ll have to decide on a policy regarding the shipping of personal belongings. My general rule is that it’s okay for crew members to include a few bags in trucks, trailers and ocean containers, as long as there’s room, and as long as these items aren’t being shipped air. Productions shouldn’t be required to ship anyone’s personal belongings back via airfreight or FedEx unless it’s been approved by the producer.

Issue a memo to the full shooting company outlining return guidelines. Here are excerpts from one of my shipping memos pertaining to returns:

If you haven’t already done so, please e-mail all return requests to __________________ (at least three days in advance), and this is the information needed:

• What are you sending?

• Where is it going?

• If you’re returning equipment, props, set dressing or wardrobe to get it off of rental, does it have to be back by a specific date?

• How many boxes/crates? Will it be packed in anything other than a box or crate?

• Will what you’re sending need to be placed on a pallet and shrink-wrapped?

• Will it require special handling?

• Can one person pick it up, or will we need a pallet jack or fork lift?

• Do you have any remaining materials or products that would be considered “haz-mat” (flammable, toxic or in aerosol cans)? If so, bring them to the production office, and we’ll sell, give them away or properly dispose of them.

• If you have haz-mat items that must be shipped back, let us know as soon as possible, so the proper arrangements can be made.

• If you need labels in advance, let us know, and the office will print them for you.

• If you need packing boxes, bubble wrap, etc., let us know that as well.

• If you need help packing, let us know in advance. Don’t just drop items off at the production office (that aren’t properly packed and labeled), because if we don’t have time to pack them, they may not arrive when you want them to.

• Anything you’re done with in advance of wrap, we can send out for you as soon as it’s ready. Just give us a heads-up, and we’ll schedule your shipment.

With regard to vendor returns:

• Provide all pertinent info: an address, phone number, con tact person and hours of operation.

• Will the vendor be expecting the return?

• Will the vendor waive rental charges during the shipping period?

For work-related materials being shipped back, I will need to know:

• If you’re wrapping at this location or will be working on the ________________ portion of the shoot.

• If your gear is to be sent any place other than ___________, and if so, where?

Just as you did when shipping your equipment/gear/materials to this location, I will need an inventory/manifest of what you’re sending back, values and the number of boxes/crates (with dimensions and weights if at all possible).

We would like as many of the returns as possible to be brought to the production office for pick-up from here. If the pick-up is going to be from the warehouse, you’ll be given a specific date and time, and someone from your department must be there to meet the truck.

Make sure all boxes/crates are numbered (Box #1 of ___, Box #2 of ___, etc.), and clearly labeled, with the address of where it’s going ___ large and easy to read.

In addition, unless it’s preapproved by the UPM or you have a prior agreement with a vendor to send back equipment/props/set dressing/wardrobe by a specific date, Production will determine how your return will be shipped.

We will not be FedExing anything back unless it’s preapproved.

No personal items will be air shipped (FedEx or air freight).

There will be no next-day or counter-to-counter returns made unless approved.

If and when airfreight shipments are approved, the transit time is generally ______ days.

For Camera, Sound, Video and other departments that have to get equipment back as soon as possible, I’m ordering a number of LD3s and would appreciate confirmation as to exactly how many you’ll need (even if it’s a portion of one). LD3s are approximately 5ft × 5ft × 5ft. The containers will be located (in)(at) _______________________________. They’ll be numbered and labeled by department.

To insure that we’ve reserved ample cargo space, I’ll need to know when you anticipate having your containers filled and ready to be picked up.

Personal Items

As a courtesy, the production shipped many personal items on (sea containers) (trailers) that were heading this way, and we expect these items to go back the same way. If you need to travel before we can get your personal gear on an outgoing container, the company will not be responsible for shipping your things back for you.

Unless prior arrangements are made and approved, both your personal gear and/or work-related materials will be delivered to the ________________ production office, and it will be your responsibility to pick them up from there.

Sea Containers and Rolling Stock

Containers will be shipped out on the following days: _______________

Accordingly, they will be picked up on ____________ (no later than __________ (a.m.)(p.m.). Transit time will take approximately __________________.

Let me know your container needs as soon as possible, so I can book the space. Also let me know:

• If it’s a container we own — the container number

• If you’re not using one we own, when you want a con tainer delivered, and where it’s to be delivered

• If you’re going to need a chassis

• If you’re going to have any extra space in your container l Where the container is to be delivered once it arrives in _________________

• Once the container arrives in __________________, how long you’re going to need it

Keep in mind that we have __________________ free days to load and unload on the other side. After that, it’s $______/day for the container and/or chassis. If it’s a container we own, let me know when you’re unloaded and completely done with it, so I can make arrangements to sell it.

Rolling Stock

It takes the same amount of time as the containers mentioned above, and this is the schedule:

All rolling stock needs to be “tendered” to the port by ____________ (a.m.) (p.m.).

Don’t take anything to the port, unless you have the booking number/reserved space in advance.

I’d like to end by urging you once again to please follow these procedures and not make any shipping arrangements on your own. It’ll make wrapping out of this location a lot less of a challenge. Also keep in mind that a missed delivery date caused by failure to follow these guidelines will be your responsibility or that of your department’s.

INTERNATIONAL SHIPPING

Whether you’re having equipment, props, set dressing, wardrobe and materials driven over the border in trucks or are having everything packed up and shipped in cargo containers via aircraft or ship, the customs and shipping part of your operation is the most time-consuming, complex and crucial part of shooting in another country. It’s not unusual for shipments to be held up at ports of entry for weeks at a time (or longer) or for shipments or vehicles to be fined or even seized because someone didn’t do their homework, someone didn’t receive or follow instructions, one document wasn’t in order or you didn’t have the right person handling your shipment. These circumstances, as you can well imagine, can create incredibly costly delays for your production. That’s why you need to work with a freight forwarder you can rely on and get involved with the choice of a customs broker.

Dealing with the regulations and the preparation involved in transporting equipment and materials into another country will involve some amount of input and cooperation from each department on your show, but it’s also a full-time job in itself for at least one individual. Some productions will establish an entire shipping department (headed by a shipping coordinator) to interface with freight forwarders, brokers and border personnel; request special permits; disseminate pertinent information to crew members; inform department heads of what’s required from their department; coordinate shipments with vendors; schedule deliveries based on border parameters; maintain accurate shipping files and logs; handle or supervise the packing, labeling and paperwork involved and deal with last-minute emergency needs. Assign at least one person on your staff to deal exclusively with these matters, but don’t be surprised if your show requires its own shipping department.

As important as it is to have a shipping coordinator, it’s equally important for someone on the other end to be responsible for receiving your incoming shipments. On smaller shows, one person may be able to handle both shipping and receiving. Mid-size and larger shows will generally require a separate person to oversee receiving. This individual would need to be equally familiar with the shipping and customs process and would:

• Monitor the arrival of shipments, alerting the shipping coordinator of any potential holdups or problems

• Cross-reference incoming shipments with daily shipping logs to make sure everything that was expected has arrived; and if not, find out why

• Make sure all shipments are delivered to the appropriate departments

• Collect and file all incoming shipping documents

• Help coordinate returns

General Customs and Shipping Guidelines

Just as one person or department should be designated to supervise and track all shipments crossing the border, each department should designate one individual to interface with the shipping office with regard to all the necessary paperwork, information, delivery schedules, etc. for that particular department. It’s also extremely important that each department keep a complete file of their own shipping documents, which they’ll also need for the return process.

I can’t stress enough the importance of keeping copies of all customs and shipping documents and accurate, organized records of all incoming an outgoing shipments. You may not only have to refer to this information on a moment’s notice, but it’ll also be essential to the return process. Remember: everything going in on a temporary basis must be accounted for on the way out.

Getting back to crew members not being allowed to make their own shipping arrangements, take that a step further by instructing them not to carry undeclared equipment or supplies in their vehicles or luggage. The transportation of all goods should be exclusively handled through the shipping department, so all corresponding documentation can be logged and kept on file. Problems arise when undocumented equipment is being returned and there are no records of it ever having entered the country to begin with.

Give yourself as much lead time as possible for all your customs and shipping requirements. As soon as anything is ordered (or even anticipated), contact vendors, shippers and your broker to ascertain the most efficient way to enter the materials, making sure the proper documentation is prepared and special permits are applied for. The more advanced notice you give those coordinating the shipment, the better prepared everyone will be and the more room you’ll have to accommodate last-minute changes and additions.

When in a hurry, there’s a tendency to want to smuggle in items without declaring them or obtaining necessary permits. When fighting to meet crucial deadlines, it’s natural to want to take shortcuts around customs regulations. Avoid the impulse, because the risks are too great. Your broker or freight forwarder can usually help you work out time-sensitive problems and are often able to secure permission from customs officials to make special crossings.

Weapons

Most countries have extremely strict regulations pertaining to the importation of weapons. It doesn’t matter if they are prop weapons and/or or made of rubber. In many instances, special permits that can take months to obtain, are required from both the country exporting and the country importing the weapons. Some countries also require that weapons of any kind be escorted by members of their military. If you wish to transport weapons into another country, check all regulations carefully, and plan ahead.

Temporary versus Definite

All shipments of equipment, wardrobe, props, etc. transported to another country and returned to the United States (or elsewhere) at the completion of principal photography are considered Temporary Exports. Each shipment is subject to a customs fee going into and out of the other country, but “duties” aren’t required on temporary exports. Most countries will give you a set length of time in which to return these items (ranging from three months to a year), with the option to renew for another specified amount of time after that. Temporary exports not returned are subject to substantial fines.

Definite exports are those items not expected to return, such as expendable supplies. Some countries will not allow you to export materials on a definite basis, and under these circumstances, you may have to make arrangements with a third-party (local vendor) who will act as the importer of record. Duties are paid on definite exports (ranging anywhere from 10 percent to 85 percent of the declared value of your goods, depending on the country). Your customs broker may ask for a deposit against duties they anticipate paying out for you.

If you export items on a definite basis that turn out to be defective, the incorrect size or unacceptable in any way, you may return them to the United States for purposes of exchange or repair. You’ll be required to write a letter explaining why you’re making the return, but your broker or freight forwarder will help you with this.

Brokers and Freight Forwarders

When transporting equipment, props, set dressing, wardrobe and materials out of the country, retaining the services of a freight forwarder is optional. Using a broker is not.

Freight forwarders will consolidate, prepare and arrange for your shipments to be exported to another country. Some have in-house brokers, packing and crating departments and their own bonded warehouses. Others have access to brokers and other services when needed. Certain countries (such as Mexico) will allow a freight forwarder to handle export documents out of the United States, but they must always work with a broker on the other end to handle the importation of goods into the other country. Exporting to most countries, however, does require a bonded broker to file the proper documents with U.S. Customs. Just as freight forwarders will utilize the services of a broker when necessary, brokers will often utilize the services of a freight forwarder to assist with shipments that have been entrusted to them. Many freight forwarders operate out of offices and warehouses located near specific ports of export (points of departure) or ports of entry and are exceptionally familiar with the import and export regulations relating to specific countries. A broker, on the other hand, generally handles multiple countries.

Get several recommendations on brokers and freight forwarders who specialize in the country(ies) where you’ll be filming, and meet with them all. It’s vital that you retain the services of people who:

• You feel comfortable with

• You believe to be honest

• Will be watching out for your best interest and not just their pocketbooks

• Have good relationships with border authorities

• Are easily accessible

• You’re willing to sign over power of attorney to

• You trust to represent you

When shipping goods to another country, the Exporter of Record is the production company or the vendor. Some vendors are great about filling out customs documents and others, not so great. But while the production is ultimately responsible, many brokers and freight forwarders will (for an additional fee) complete the necessary paperwork for you. If you’re doing it yourself, ask your broker or freight forwarder how they want you to prepare the paperwork. If you’ve done it before, show them the format you use, and make sure it’s okay with them. You’ll find a few forms at the end of this chapter that should be helpful.

Also, make sure to issue additional insured certificates of insurance to your customs broker and/or freight forwarder.

Methods of Importing Goods on a Temporary Basis

There’s one set of documentation presented to U.S. Customs when transporting goods out of the United States, another set upon entering a foreign country, another set when the goods leave that country and yet another when re-entering the United States All countries have procedures allowing for the temporary importation of goods to cross their borders; and not only are the procedures different in each country, but they’re also frequently subject to change. Incoming goods are all categorized by a harmonized code, some codes covering a broad range of items, while others are quite specific. Many countries have harmonized codes (and related procedures) that are unique to the entertainment industry, but harmonized codes are also subject to change.

Many countries require carnets with bonds;, others require any combination of pro-forma shipping invoices (a.k.a. shipping manifests or commercial invoices), certificates of registration, temporary import bonds (TIBs) and/ or cash deposits. The following describes some of these requirements in more detail:

Carnets

Accepted in over 50 countries and territories, carnets may be used for unlimited exits from and entries into the United States and foreign countries and are valid for one year. They eliminate value-added taxes, duties and the posting of security normally required at the time of importation. They simplify customs procedures by allowing a temporary exporter to use a single document for all customs transactions and to make arrangements in advance at a predetermined cost. They facilitate reentry into the United States by eliminating the need to register goods with U.S. Customs at the time of departure. There are three basic components to the carnet application process: preparation of the General List (inventory of goods being transported, listed by description, serial numbers and value), completion of the carnet application and provision of a security deposit (bond). All carnet applicants must furnish the USCIB (U.S. Council for International Business) with a security bond, the amount of which varies according to the country(ies) visited. The bond acts as collateral and will be drawn upon to reimburse the USCIB in the event it incurs a liability or loss in connection with the carnet or its use. The amount of the nonrefundable bond is based on the total value of the goods listed on the carnet. The minimum is 40 percent of the value, although 100 percent is required for goods being transported to Israel and the Republic of Korea (the production is expected to pay 1% of the security deposit, or a financial statement of the company applying may be sufficient to underwrite the bond). Security deposits are paid in the form of check or money orders, refundable claim deposit or surety bond. The normal processing time for a carnet is five working days. Basic processing fees (around $350) are determined by the value of the shipment. Expedited services are an additional $150. For a manifest that’s more than a page long, there’s a $10 fee for continuation pages (yep — that’s $10 for the second and each subsequent page). You can download application materials from USCIB’s website (http://www.uscib.org/index.asp?documentID=718).

In addition to listing all goods being transported, a carnet includes the approximate date of departure from the United States; all countries to be visited and the number of expected visits to each; number of times leaving and re-entering the United States; and additional countries transiting (when merchandise is transported by land and must pass through or stop in a country that lies between the country of departure and the next country of entry).

Carnets don’t cover expendable supplies or consumable goods such as food and agriculture.

Additional information on carnets, carnet applications, bond forms and Carnet Service Bureaus can be found on the USCIB website at www.uscib.org/index.asp?documentID=718.

Certificate of Registration

Some countries that don’t accept carnets will allow you to register equipment, props, set dressing and wardrobe before transporting these goods out of the United States. Registration is primarily used for goods that weren’t manufactured in the United States. If you have a manifest containing goods from various countries of origin, then everything can be registered. Stamped on the way out of the country, the original registration documentation is required for reentry into the United States.

You can download a blank Certificate of Registration form directly from the Internet by going to http://forms.cbp.gov/pdf/CBP_Form_4455.pdf.

Pro-Forma Shipping Invoices

Also referred to as shipping manifests and commercial invoices, pro formas are also accepted by countries that don’t accept carnets, although some countries require the combination of certificates of registration and shipping manifests. This completed form would indicate a description of goods being sent, a declaration of temporary or definite export, country of origin (country the item was manufactured in), declared value for customs purposes, total weight of each item/box and weight of total shipment.

Descriptions of goods being shipped should:

• Include year, make, model and serial numbers (whever applicable).

• Include the dimensions of an item (if applicable).

• Include the primary material content of the goods, which is especially important in the exportation fabric and clothing.

• Note the presence of dangerous goods — anything that could become explosive, flammable, toxic or hazardous. These materials must be manifested and packed separately and accompanied by MSDS (see earlier section on dangerous goods).

• Be easy to understand. Don’t use part numbers or overly technical descriptions without a brief explanation as to what the materials are and what they’re used for. People who aren’t film technicians must translate and assign code numbers to each item, so make it “border-friendly.”

• Clearly indicate where each item is, so if you have various crates, boxes, shelves, etc., each location on the truck or cargo container would be numbered, and you would, for example, indicate Box #1, then list the contents of the box underneath that heading. If you have several boxes or crates each containing several items, list the contents of each on one page of the pro-forma. This will make the manifest easier to process, and the shipment easier to inspect at Customs. As you’ll note on the sample pro-forma shipping invoice form at the end of the chapter, there are spaces to indicate Page___ of ___ and Box___ of ___.

It would also speed up the process if you could manifest all U.S.-made goods on one pro-forma and all foreignmade goods on another. Don’t worry about it too much if your equipment packages contain items from various countries of origin — but if you can, it would help.

If you’re manifesting a drawer full of tools, you could list “10 screwdrivers” without having to list the size and type of each one. You could indicate “10 assorted pieces of tubing” without having to record the length of each piece. You can combine descriptions on many small items contained in one drawer or box when describing like items. Certain kits or packages can also be manifested as such without having to describe each piece contained within the kit or package. Check with your broker for more specific guidelines on manifest descriptions.

If your shipment fills more than one truck or cargo container, you must manifest the shipment by the truckload or container, and each pro-forma should indicate the truck or container number, so it’s clear as to which items would be found in which.

• Indicate the type of packaging. If something should get lost or separated from the rest of the shipment, it’s important to know what kind of a case, box or crate it was packed in and what color the case, box or crate is. The more information you can provide, the easier it is to keep all the pieces of your shipment together.

For tracking purposes, each pro-forma should include the name of your production and/or production entity. It must also have a shipping manifest number. The shipping manifest number, along with a customs entry number will be what identifies each shipment coming in and going out of a country; and ID numbers will be kept in your files, your brokers’ files and in Custom’s files (and computers).

You can devise your own system to use as a shipping manifest number, or use the one described here, which has proven to be quite successful. It’s an eight-digit number followed by a two-or three-letter department code. An example would be:

Shipping Manifest No: 10-09-27-01-PD

10 = the year

09 = the month

27 = the day

01 = first shipment for that day

PD = Production Department (department code)

Suggested department codes are as follows:

| Accounting | AC |

| Aerial | AE |

| Animals | AN |

| Art Dept. | AR |

| Camera | CAM |

| Cast-Related | CR |

| Catering | CA |

| Construction | CS |

| Communications | CM |

| Craft Service | CRS |

| Editorial | ED |

| Electric | EL |

| Extras | EX |

| Grip | GR |

| Locations | LOC |

| Make-Up/Hair | MH |

| Marine | MR |

| Medical | ME |

| Miscellaneous | MS |

| Paint | PT |

| Production | PD |

| Props | PR |

| Publicity | PB |

| Scaffolding | SF |

| Security | SC |

| Set Dressing | SD |

| Sound | SN |

| Special Effects | SFX |

| Still Photography | SP |

| Stunts | ST |

| Teaching Supplies | TS |

| Transportation | TR |

| Video Assist | VA |

| Video Playback | VP |

| Visual Effects | VFX |

| Wardrobe | WD |

When completing a pro-forma shipping invoice, you’re required to declare the value of each item in the shipment. There’s an unwritten understanding that values are reduced for customs purposes. A good guideline would be to declare 40 percent of the actual value on all temporary exports and 30 percent on definite exports, although depending on the item, you may go lower in some instances. On definite exports, the lower your value, the less you will pay in duties. Use your best judgment, and keep in mind that it’s acceptable to reduce values for customs purposes and more so on “used” items. Just play it safe by not going too low on everyday items that customs officers would be familiar with. Save your creativity for film-related items that people outside of our industry know little about. Remember, however, if the value you place on something is too ridiculous, it could raise suspicions and delay your shipment.

If possible, each department should be responsible for and prepare their own pro-formas, the process of which is incredibly time-consuming. Consider hiring additional production assistants (trained to do shipping invoices) to assist your departments and vendors with this operation.

Temporary Importation Bonds (TIBs)

TIBs are also accepted by certain countries that don’t accept carnets. This bond would be based on a percentage of the declared value of an incoming shipment. The bond insures that all appropriate fees will be paid upon returning goods back out of the country.

In-Bond

When merchandise is being sent from a country other than the United States, but must travel through the United States to reach its destination, it’s sent “in bond,” so no duties are paid until the merchandise reaches its final destination. These loads are sealed and transported by a bonded carrier and are generally consigned to a bonded warehouse. Bonded loads must be returned in the same manner.

Shipper Export Declaration

This is for shipments on their way out of the United States that are valued at more than $2,500 and/or are temporary exports. You can be hit with a substantial fine for not having a Shipper Export Declaration when necessary. Your broker or freight forwarder will have this form.

Again, each country has different regulations. Canada, for example, has what they call an Equivalency Requirement: if equivalent equipment is available in Canada, you may have difficulty bringing similar U.S. goods across the border. So allow yourself enough lead time to ascertain requirements and restrictions, apply for permits, fill out applications, gather serial numbers and the value of your equipment and post bonds and/or deposits. Customs and Immigration are government entities, and no matter how urgent our needs may be, they’ll work within their own time frame and will not make exceptions for anyone — not even filmmakers.

Transporting Goods Across the Border

This is how it generally works:

• Production submits their portion of the necessary paperwork to the freight forwarder or broker.

• The broker makes sure all required documents are in order and/or generated.

• A Shipper Export Declaration is issued and registration forms are completed if necessary.

• Arrangements are made for picking up and delivering your shipment(s) to the port of export, or in some cases, right to the border.

• The shipment arrives at the port of export or port of entry (border), and the freight forwarder or broker checks the shipment against the documentation, making sure everything is in order. It’s the responsibility of your freight forwarder/broker to make sure that your shipment will clear Customs, so if the paperwork doesn’t match the load in any way, the shipping documents must be amended or the load possibly separated. Temporary and Definite exports must also be separated, as they’re not allowed to cross in the same shipment.

• Duties for definite exports are paid.

• After the merchandise has been checked, duties paid and the load approved for clearance, the shipment is cleared through a U.S. Customs export facility.

• U.S. Customs will not generally inspect outgoing loads other than “in-bond” shipments and heavy machinery. U.S. Shipper Export Declarations and registration forms are presented and stamped at this time.

• Once cleared through U.S. Customs, the shipment is ready to be transported to and cleared through Customs of the other country (with the proper Customs Entry document accompanying the shipment).

• At importation, the shipment is checked against the documentation and serial numbers are randomly checked. (Some countries have secondary inspection areas as well.) Once customs officials have cleared your shipment, the documents are stamped and the load released.

Fees

Those preparing to film out of the country for the first time are often unprepared for the true costs of shipping and customs. Make sure your broker lets you know up front what the anticipated costs will be (door-to-door), and confirm that the price includes any of the following fees that are applicable to your shipments:

• Customs fee (based on value of goods and country of origin)

• MPF (Merchandise Processing Fee) at point of entry

• Freight forwarder and/or broker’s entry fee

• Fee for freight forwarder or broker special services

• Rush fees

• Duties on definite exports

• Registration fees

• Airline fees

• Delivery or handling fee

• Airport terminal fee

• Inspection fee

Packing and Labeling International Shipments

If you’re packing items that have different countries of origin, it would be helpful to pack U.S.-made goods separately from goods manufactured in other countries.

Trucks: Make sure all drawers, shelves and boxes are labeled (i.e., Box #5, Drawer #1, Shelf #3, Rack #4 and so on), and that each area is both accessible to inspection and easy to locate. The contents of each box, drawer and shelf should be reflected on the shipping manifest.

Cargo Containers: They should be packed with boxes, cases or crates labeled as indicated above. Individual pieces of equipment or set dressing should be tagged and labeled the same way — Set Dressing — Piece 1 of 3, etc.

All items in the trucks or cargo containers need to be easily assessable to spot-check by customs officials. No crate should be secured so tightly that it can’t be opened and inspected. Trunks and cabinets with keys should be kept unlocked.

Any time you can take a picture of the inside of a packed truck or cargo container or draw a diagram indicating where every numbered box-item-shelf-bin is located — the faster your shipment will move through customs. Know your inventory and be familiar with how it’s laid out.

When purchasing new equipment or supplies, remove all price tags. Having one value on a price tag and a different declared (possibly reduced) value on the accompanying documentation will create a customs headache and may hold up your shipment.

Don’t mix temporary and definite exports, don’t include personal items with commercial goods and pack dangerous (hazardous) goods separately.

Providing Information to Vendors

Once an order is placed for equipment or materials you’ll need on location, it’s important for your vendors to have a contact to deal with to coordinate shipping and customs requirements and to make sure they’re aware of all applicable regulations. They need this information, because:

• They’ll have to supply you with the information you need to prepare your shipping documentation (some vendors, such as Panavision®, will prepare shipping invoices for you).

• They need to know how to pack, label and load correctly, and not doing so will delay delivery of their shipments.

• They need to know how long it’ll realistically take to get their equipment and supplies to location.

• If they’re shipping or making deliveries to the border, they need to know who your border rep is, where he or she is located and the hours in which deliveries can be made — including the optimal time to arrive in order to cross goods that day.

• A vendor who is unaware of proper procedures may attempt to ship equipment or supplies directly to you on location without knowing the most direct or effective method, and shipments could be delayed.

To save on time and avoid having to explain the same set of instructions over and over again, e-mail or fax your vendors a form letter explaining shipping and customs procedures and if applicable, include a map (with address, phone number, fax number and contact names) to your border rep’s warehouse.

Returns

Your customs broker will give you instructions as to how best to handle your returns. Shipping goods back from a foreign location can be equally as time-consuming as shipping them there to begin with; this is where having kept complete, well-organized shipping and customs files will be a tremendous asset to the process.

It’s significantly easier to return everything all at one time, packed in the same configuration it was sent in. Unfortunately, returns are often made on a piecemeal basis.

Each piece of equipment as it’s listed on a carnet must be returned at the same time under that same documentation. Even if you’ve completed using one or two pieces of equipment sooner than the rest of the package, you can’t return them early. You can stagger returns, but each shipment must include the entire list of goods as documented on each carnet.

Certain types of registrations require that entire shipments be returned in the exact configuration in which they entered a country. There are other countries that will allow you to return merchandise gradually. As you’re ready to return individual pieces of equipment that came as part of larger shipments, you’ll be canceling just that portion of the customs entry document it came into the country on. If you’re returning several pieces of equipment, set dressing, props, etc. that all came in at different times as part of different shipments, each item must be matched up to its original pro-forma shipping invoice and customs entry form. Because your brokers must go through the same procedures to cancel an individual item as they do to cancel an entire shipment, returning an item or two at a time could become more costly than waiting to return an entire shipment at once. Weigh the costs of canceling individual items with the value of the item(s) you’re returning or the rental you’re paying on those items.

Your broker will generate a new customs document for each returning shipment. Once this is issued, the shipment can’t be altered in any way. You can’t decide to add something at the last minute, take something out or switch one piece of equipment for another. If the paperwork doesn’t match the shipment exactly (down to the correct serial numbers), the shipment could be held up at the border indefinitely. Never include personal items with returning commercial goods. That’s another sure way to have your shipment held up.

Film and Dailies on a Foreign Location

Raw stock can’t be put on a carnet. It’s generally considered a temporary export, gradually accounted for as it leaves the country in its exposed state. Some countries require a bond upon entering. Others assess a tax or duty to the film as it leaves the country based on a percentage of its declared value. Once dailies are sent back to location in the form of a viewing print or DVD, they’re again considered temporary exports and will be canceled out upon return.