Chapter 21

Travel and Housing

INTRODUCTION

One of the best things about being in this industry is the chance to travel, but making all the arrangements to travel a cast and crew to a distant or foreign location can be a demanding and often frustrating and thankless job. So my hat is off (and yours should be, too) to all the travel coordinators, production coordinators and assistant coordinators who take on these responsibilities.

TRAVEL CONSIDERATIONS

The act of traveling cast and crew to a distant or foreign location is well-regulated, starting with the production company’s obligation to carry a Travel Accident Policy as part of their insurance package. Additionally, union and guild guidelines stipulate which individuals should be afforded first-class tickets (if first-class travel is available to your location) and that all personnel traveled to a distant location must return to the point of origin upon completion of their work assignment. It’s not uncommon for nonunion shows to follow the same return-to-origin procedure, as it safeguards the production’s liability. That’s why studios and production companies make it perfectly clear that they’re not responsible for individuals who wish to travel on their own. However, smaller independent companies are sometimes a bit more flexible when it comes to travel, and individuals who make their own travel arrangements may be reimbursed for their mileage or the equivalent price of a plane ticket. Should you be approved to travel on your own, make sure to give the production office a copy of your itinerary.

Production coordinators and/or assistant coordinators were the ones who traditionally handled all travel and housing arrangements when a film unit shoots on a distant or foreign location. Some shows, however, are so large and/or their many locations so spread out, that their production coordinators would end up with little time for anything other than travel. It’s therefore fairly common now for larger shows to employ a dedicated travel coordinator. But whether you can hire a travel coordinator or not will largely depend on how many members of the cast and crew will be traveling and whether your budget can accommodate the additional person.

An issue that comes up often and that I would like to clarify is that it isn’t the production or travel coordinator’s responsibility to make personal travel arrangements for the friends and family of cast and crew members who wish to come visit on location. If asked nicely, and if they can find the time in their already hectic day, they might be willing to do so; but this would be their choice and not something that should be expected.

Major studios and several independent production companies have their own in-house travel departments; and when doing a show for them, one of their travel reps will be assigned to your project. The production or travel coordinator will then interact with this person for all the production’s travel, limo, rental car and chartered flight needs. The travel coordinator will also be given an after-hours contact person and number to call for travel needs that may arise after the rep has gone home for the evening. (In some cases, the assigned travel rep may be the after-hours contact person as well.) The way the process generally works is that the production or travel coordinator will fill out a request form called a “TA” (travel authorization) and/or a purchase order for the travel being requested. Information is verbally given to the travel rep, so he or she can start checking reservations and tentatively lining up itineraries. At the same time, the TA is sent to the show’s designated production executive for approval or a purchase order for the travel costs is approved by the UPM. Once approved, a copy of the signed TA or PO is faxed, e-mailed or handed over to the travel office, so arrangements can be finalized and tickets purchased. At some studios, the TA system is processed entirely online.

The travel rep will then fax or e-mail a confirmed itinerary back to the production office, and electronic tickets are arranged for. If you’re not working for a studio, there is no TA system in place and no production executive to approve travel arrangements, then it’s the producer’s responsibility to sign off on all travel before final reservations are made and tickets are purchased. Sometimes, both the producer and production executive are required to authorize travel.

If you’re not associated with a studio or production company that has its own travel department, you’re likely to enlist the services of an independent agency and agent to help you with your show. Number one rule: use an agency that’s familiar with how film companies operate (and can take ever-changing travel plans in their stride), and ask for (and check out) references from other people who have used them on other shows. Also, make sure they:

• Can offer an after-hours contact and phone number

• Have good relationships with airline reps who can offer group discounts and help with product placement deals

• Have good rental car and limo service contacts

• If desired, can offer Meet & Greet services at the airport (this service entails having someone at the airport to meet arriving cast and crew, help them with their luggage and check-in, escort them to a VIP waiting room, etc.)

• Can help with chartered and helicopter flights if necessary

There are going to be times when travel or production coordinators find themselves up the creek without the help of an in-house or private travel agent and must deal directly with the airlines, limo companies, rental car companies, etc. So it’s important for them to build travel industry relationships on their own, or at the very least, maintain a list of solid contacts they know they can rely on.

Crew travel dates are dictated by the production manager. As for the cast, the second ADs will usually be the one to anticipate travel dates by considering contractual obligations, rehearsal schedules, wardrobe fittings, hair and make-up requirements, etc. But it’s the producer who has the final say on when the cast travels.

Union and guild regulations specify that a travel day is a work day (paid at straight time, so no premium pay is incurred). The cast receives a full day’s pay for a travel day, and crew members are entitled to a minimum four-hour day or maximum eight-hour day, depending on their particular union/guild, where they’re flying from and to and the overall deal they (or their agents) have negotiated. As it behooves everyone involved for travel times to be as short as possible, it’s customary to book early, nonstop flights, so if there are any delays, there’s also some wiggle room. The requests of those who prefer taking the last flight of the day are usually discouraged unless approved by the producer.

On days when the cast and/or crew travels and then works, their call time is the time their flight takes off. If travel is scheduled following a partial day worked, then they’re off the clock when they arrive at their agreed-upon destination. So assuming that flight options are available, a good travel coordinator will be aware of how travel schedules can affect payroll (and thus the budget).

The production or travel coordinator is also responsible for the following:

• As applicable, filling out TAs and/or POs

• Scheduling direct, nonstop flights whenever possible

• Providing those traveling with their itinerary as well as all applicable contact and emergency phone numbers; also, reminding everyone to carry a photo ID (passport if applicable) with them

• Helping to arrange for passports on short notice when needed

• Confirming that existing passports won’t expire while a cast or crew member is on location. The rule of thumb is that they should be valid six months past the date of departure

• Contacting actors’ agents regarding travel and housing arrangements

• Arranging for ground transportation to and from airports for traveling cast and select crew members. Most crew members are expected to make their own arrangements and are reimbursed for the reasonable cost of ground transportation (cabs, airport shuttle vans, etc.) to and from airports. (They’re also reimbursed for luggage fees.)

• When called for, arranging for Meet & Greet and/or the use of the VIP waiting room at the airport

• If everyone is not traveling in one group, making sure cast and crew members know where they’re going to be met when they arrive: at the arrival gate in the terminal, in baggage or outside of baggage. (Awaiting drivers generally hold up signs with the name of the show or the names of arriving passengers.)

• Maintaining an updated list of airlines that fly to and from your location, phone numbers of the airlines, contact names of the airline reps and a schedule of all flights to and from the production’s locations.

• Preparing Movement Lists and Individual Travel Itineraries.

• Dealing with the hotel(s) and rental units, negotiating rates, booking rooms and locating housing for the show’s VIPs (if there isn’t a dedicated housing coordinator on the show).

They’re also constantly having to deal with shooting schedule changes that could potentially affect the travel schedules of the entire shooting company. They interact with producers and directors who often can’t make up their minds when they want to leave or where they want to stay as well as actors and their reps, one of whom can sometimes be more labor-intensive than 50 crew members. My friend Mimi McGreal is the best travel coordinator I know and has the patience of a saint. When on a show, she’s on call 24/7 in case changes are made and/or someone needs to be brought to location or sent home at the last minute. It’s also not unusual for her to be awakened extremely early on a Sunday morning by a crew member who’s unapologetic about calling so early and whose only concern is being able to once again change his flight arrangements home — even though he’s not leaving for another two days.

General Travel Information

For union cast members, the transportation provided must be first-class, unless six or more performers travel on the same flight and in the same class within the continental United States — in which case, coach class is acceptable. (This rule is most often only used for stunt performers, as most shows provide actors with first-class travel regardless of whether six or more performers are on the same flight.) Whether cast members who can be flown coach actually are will depend on their individual deals, the type of flights available to a specific location and the accessibility of first-class seats when needed. Bus transportation is acceptable when no other means are available. For interviews and auditions only, performers may travel other than first-class on a regularly scheduled aircraft. When traveling internationally, all performers are flown first-class.

As for the crew, certain people are afforded first-class travel by virtue of their affiliated union regulations and others by virtue of their deal. On domestic flights (including flights to Mexico and Canada), everyone else is usually transported via coach class. On international flights (excluding Mexico and Canada), those not flying first-class will almost always be flown business-class, pending seat availabilities.

Should individuals not being afforded first-or business-class travel wish to take it upon themselves to upgrade their class of travel, they can do it on their own by paying the production for the difference in cost or by using personal frequent flyer miles. Keep in mind, however, that once crew members choose to use their flyer miles to upgrade, they must do it on their own. At that point, the travel coordinator can no longer access their records, and they become responsible for making all future travel changes.

For the latest on the ever-changing laws and guidelines pertaining to travel, packing, what constitutes a carry-on, what can be carried on, getting across borders, etc. (information that you’ll want to provide to your cast and crew), check out the following websites, which provide a tremendous amount of invaluable information.

Transportation Security Administration: www.tsa.gov U.S. Customs and Border Protection: www.cbp.gov Department of Homeland Security/Travel Information: www.dhs.gov/files/travelers.shtm

When traveling to another country, be aware that most countries will not permit you to carry your personal tools, equipment or desktop computers (tools of the trade) with you unless they’re preregistered or under a carnet (depending on the country), and you can provide the proper documentation.

Movement Lists and Individual Travel Itineraries

It’s essential to keep certain people informed as to who is traveling and when — most of all, the people who are doing the traveling. Movement lists provide a basic schedule of who is traveling, when and how. They’re generally distributed to the producer(s); director; production manager, supervisor and coordinator; assistant directors; production accountant; transportation coordinator; location manager (if applicable); studio or production company executives and the insurance company. This information is used to determine per-diem payments, schedule vans and drivers for airport pickups, establish how many hotel rooms will be needed on any given night, etc. Department heads from Hair, Makeup, Wardrobe and Props and the stunt coordinator will also often request copies of movement lists, so they know when cast members are arriving on locations and can schedule fittings and meetings, and Props can fit performers with jewelry, eye glasses, etc. At the end of this chapter, you’ll find a general Movement List form that can primarily be used if many (or all) members of a shooting company are scheduled to travel at the same time. Also included is a Quick Reference Travel Movement form, which can be used to track any number of individuals traveling to any location.

An Individual Travel Itinerary (also located at the end of the chapter) is used to inform people traveling of all the specifics associated with their trips, including details relating to ground transportation to and from the airport; their flight; their plane ticket and per diem; where they will be staying; the address, phone number of the location-based production office and when they’re currently scheduled to return.

HOUSING

On huge shows, with hundreds of cast and crew members arriving from various parts of the globe, the production may hire a housing coordinator to handle nothing else. And while I’ve never worked with one, there are also corporate housing firms that specialize in finding and negotiating hotel/motel/rental deals for shooting companies on location. On fairly large to mid-size shows, when a majority of the cast and crew is flown in, housing will generally fall under the domain of the travel coordinator. On smaller shows, with smaller budgets and for which not many people are transported to location, it would be the production coordinator and/or assistant coordinator whose laps these duties would fall into.

Choosing hotels, motels and rental units on location will depend on where your location is (you want them to be as close to your shooting locations as possible to cut down on daily travel time back and forth to the set), the availability of lodging in that town, how long you’re going to be staying and your budget. Not all hotels can accommodate an entire shooting company, so while one is generally selected to serve as the production’s headquarters, often two or three are used to house an entire shooting company.

Factors to consider when scouting hotels:

• The most obvious — the cleanliness of their rooms. (No matter how inexpensive they are, if they’re not clean, keep looking.)

• Will they give you a fair group rate (based on the going room rates in the area)?

• Will they give you the same per room rate whether a room’s furnished with a king bed, two queens, and is occupied by one person or two?

• Have they housed other film companies before? Great if the answer is “yes” and they still want your business.

• Do they have suites available for the producer, director and lead cast?

• Do they have a restaurant and/or coffee shop, and would they be willing to open early or stay open late to accommodate shooting hours?

• Do they offer room service? If so, during which hours?

• Do they have ample parking for all company vehicles (trucks and trailers included)?

• Is the cost of parking included?

• Do they offer free Internet?

• Are there restaurants, markets and shops within walking distance of the hotel/motel?

• Would your catering and/or camera trucks be able to pull up to an electrical outlet, so they could plug in for the night?

• If necessary, do they have a banquet room that could be used for meetings?

• If you’re going to be shooting nights, would they be willing to reschedule housekeeping — cleaning rooms in the evening and not vacuuming or doing anything noisy near crew-occupied rooms during the day?

• Do they accept pets (there are always a few people who travel to location with their dog or cat)? If so, is there an additional charge or any special requirements?

• If needed, would you have access to their copier and fax machines? If so, how much per page would they charge? And if so, would you have access to these machines at any hour of the day or night?

• Do they have washing machines and dryers that the production could use when not in use by the hotel/motel?

• Would they be willing to throw in a meeting or banquet room or two or a few adjoining guest rooms that could be converted into temporary offices at no extra cost? If so, would you be allowed to have outside phone lines installed in those rooms (enough to accom modate phone, fax and DSL lines)?

• Would they be able to supply refrigerators and/or microwaves in the rooms (if not already there)?

• For those people who might need to work from their rooms, would rooms have a phone that’s located on a table or desk, and would it have a sufficiently long cord? (It’s not easy to work from a phone with a short cord that’s right next to the bed.)

• Would they be willing to waive the cost of local phone calls?

• Would they mind posting a call sheet and map in their lobby each evening?

Not many hotels or motels will be able to accommodate everything on your wish list, but the more they can say yes to, the more desirable they become.

Once you’ve selected a hotel and negotiated a deal, you’ll be expected to sign a contract and pay a deposit (usually to be applied toward the final bill). Most deposit requests are for one night’s stay for the entire shooting company. The agreement that you sign should include provisions for schedule changes or cancellation. As the hotel has agreed to block a significant number of rooms for a specified period of time, much will depend on how much notice you can give them in the event of a change and whether they have sufficient time to rebook the rooms. Many of the larger hotels will give you the flexibility of canceling up to seven days prior to scheduled arrivals. After that, the minimum they may require is a cancellation fee equal to your first night’s reservations. With a sufficient amount of notice, you should be able to postpone your hotel dates without penalty — whether it’s for one person or the entire company.

Make sure the hotel understands that the production is paying for rooms and tax only. Everyone staying there will be responsible for their own incidental charges, and the hotel is responsible for obtaining a credit card from each individual against their incidentals. As this is standard procedure, most crew members are good about doing this.

As part of their deals, principal cast members, producers, directors and DPs are often given a weekly living allowance while on location that incorporates their housing. If there are individuals on your show who have this type of deal and choose to stay at the hotel, the hotel should be given a list of their names and informed that they’ll be responsible for the cost of their rooms, plus tax, as well as their incidentals. Also under these circumstances, inform those involved of their room choices before reserving suites for them. Because they’re paying for it, they may want less-expensive rooms (or maybe not), so ask.

Your main hotel contact is generally the sales manager and possibly one other individual from the sales department or front desk. Production-related requests should be directed toward these people only. Likewise, inform your crew that any complaints they might have about their rooms or the facilities are to go through the production office. The greater the number of people who get involved, the greater the chance for miscommunications and mistakes.

Without even being asked, cast and crew members will generally inform you (prior to traveling to location) as to their preferences in hotel rooms. And if you use the Crew Information Sheet (found in Chapter 6), it asks for hotel preferences, which can be a big help when making reservations. (Let it be known, however, that granting these requests will solely be based on hotel availabilities.) Supply the hotel with a list of arrivals (names, dates and approximate times of arrival), the type of room each person has requested (if available) — a suite, king-size bed, two beds, a room on the ground floor, etc., and indicate when each person is scheduled to check out. Keep the sales manager or reservations clerk alerted as to any last-minute additions and/or changes in arrivals and departures.

Make sure the hotel rooms are ready for cast and crew members when they arrive, even if they arrive early in the day (before check-in time). If you let them know in advance of your need for early check-ins, they may waive the extra night’s fee if the hotel has vacancies anyway, or they may just charge you a half-day fee for an early check-in.

Your hotel office space should be able to accommodate a UPM, production coordinator, assistant coordinator and a couple of PAs, a two-to four-person accounting office and possibly a transportation office. The camera and sound departments might work out of their trucks/trailers, but occasionally you’ll need rooms to store equipment. You’ll most likely need ample space for Wardrobe as well as Editing. If rooms for equipment, Editing, and Wardrobe are at the hotel, they should be on the ground floor and have dead-bolt locks on the doors.

Keep your own list (see the Hotel Room Log at the end of the chapter) of when each person checks in and out, and compare it against the hotel bills. It may be helpful to keep a second list (in alphabetical order) for quick reference in addition to the Hotel Room Log that categorizes everyone by department and arrival date.

If the hotel is busy, think about reserving a couple of extra rooms, just in case the schedule changes and additional cast or crew have to be brought to location earlier than anticipated (most hotels won’t charge you for holding extra rooms, as long as you release the ones you won’t be needing early each afternoon, so they can be rented that night). Find out the status of available rooms should your show run over schedule and the company have to stay longer than anticipated. Check out the availability of rooms at other hotels and motels in the area should they be needed.

In order to create a positive experience for all involved and give the hotel reason to welcome other film companies in the future, a good relationship with the hotel can’t be underestimated. The hotel management needs to feel that those they’re dealing with — the travel or housing, coordinator, production coordinator and/or UPM — are on their side and that they’re not being taken advantage of. It’s therefore in everyone’s own best interest to treat the hotel staff with courtesy and respect. Never come in with a sense of entitlement by virtue of the fact that you’re a film company, and take the hotel’s concerns seriously when there’s a problem.

Under the best of circumstances, it’s been my experience that certain members of the hotel management staff become like part of the crew. And it’s amazing how far they’ll go to keep their guests comfortable and (often) entertained — like those who host weekend barbecues, parties and other events for the cast and crew. But this only happens when consideration and appreciation is reciprocal.

There’s Always Someone

It’s not unusual to have a problem with a member of your cast or crew who’s become a nuisance for the hotel. Problems might include smoking in a nonsmoking room, making too much noise and disturbing other guests, damaging hotel furniture or using drugs. I was on a show once where the lead actor’s dog was wreaking havoc on the hotel, and we were given a choice — the dog goes or the entire shooting company goes. Guess which option we chose (and fast)? Oh, and by the way, for those faced with cast or crew members causing trouble at a hotel, you might be well-served by letting the producer step in on these matters.

It’s also not unusual to encounter individuals on the shooting company who aren’t happy with their accommodations. The travel, housing or production coordinator needs to be helpful whenever possible and take the time to listen to all complaints, because many are legitimate. Sometimes alternatives can be offered, and the solution is an easy fix. But there are other times when it is what it is, and the problem isn’t fixable. The most common cause for this usually stems from remote locations and small towns that offer very few hotel/motel options and rooms that leave something to be desired. As long as the production does the best it can with what it has to work with, most cast and crew members will roll with the punches. I worked with a UPM once who always asked for the worst room in the hotel. That way, when someone on the crew complained, he’d take the upset person to his room and offer to trade with them. The complainer would usually rush back to his or her own room — happy to have it.

Those handling housing have to be sensitive to the needs of their cast and crew, be honest about the accommodations being provided (so everyone knows in advance where they’ll be staying) and be able to offer options whenever possible. Those who complain all the time and can’t be appeased by a travel, housing or production coordinator should be invited to take their cases to the UPM.

I was once brought in on a film that was shooting in a small southern town that had only one old, rundown motel. When you sat on the edge of the bed, the mattress sank to the floor. And when you held up the old, stained bedspread, it was so thin, you could see through it. There were holes in the carpet. And the shower — well, you wouldn’t want to step foot in it without shoes on. The next town over had a much nicer motel, but there weren’t going to be any availabilities for a while, so we were stuck — all of us. I came to the production late and hadn’t been around when the motel deal was made, but after seeing my room, I promptly marched to the hotel manager’s office to see if anything could be done to improve our accommodations. I was told that renovations had been ordered but weren’t scheduled to start quite yet. I pleaded for at least new bedspreads and was told they were on order. And each evening when I arrived back at the hotel after work, I checked in at the front desk to ask if the new bedspreads had arrived. And for weeks I heard: “Sorry, no, not today … check back tomorrow.” Word soon spread among the crew, and they would tease me about my quest for the new bedspreads. About two-thirds of the way through our shoot, rooms opened up at the motel in the next town, so some of us moved. But I still checked every evening, and the bedspreads finally did arrive — on the day we wrapped.

For years afterward, when I’d mention to my friend Pat (who was the unit publicist on that show) that I’d been on a trip, instead of asking me if I’d had a good time, she’d ask me how the bedspread was.

The moral to this story is to know what you’re getting into before you get there, and be ready to make it better or shoulder the complaints you’re going to be getting.

Alternative Housing

Once on location, even if your hotel room isn’t quite what you had hoped, you’re not likely to be spending much time there. And it definitely has its advantages — like having your room cleaned and your bed made up for you each day, the room service and/or the coffee shop downstairs (as if we have much time for cooking anyway). But when on location for an extended period of time, some prefer to stay in rental units — apartments, condos and/or homes. Not everyone likes living in a hotel room for months on end, and there are those (like me) who like having a kitchen for those rare occasions when I can cook my own meals or have friends over for dinner. In fact, when on location in Squaw Valley, Mexico and Kauai, I have lived in beautifully furnished condos with an extra bedroom so that I could invite friends to come visit. It worked out great — especially for my friends. The downside for me was that because I work so many hours, I rarely got to enjoy much time in these lovely condos, although the little time I did get was great. It really got to me while in Kauai, especially in the mornings when I’d walk out to my cute little Mustang convertible carrying my computer and briefcase, while everyone else emerging from their condos were carrying surfboards, picnic baskets and beach towels. But oh well, if you’ve got to work long hours, Hawaii isn’t a bad place to be.

Most productions will offer a housing allowance to those who prefer not to stay at the hotel — usually the equivalent of what a hotel room would cost. Some will pay the allowance on a weekly basis (usually the Thursday following each week, just like a paycheck), some on a monthly basis, depending on the show and who’s making the rules. If you’re getting an allowance, Accounting may ask you to sign a form releasing the production from any further responsibility pertaining your housing, which also means that if you decide on a rental unit that requires a security deposit or month’s rent up front, and you’re only getting your housing allowance once a week, you’re on your own. Unless it’s part of your deal, the production will not pay the deposit for you.

But there are individuals whose deals do include luxury housing — certain actors, producers, directors and DPS — again, depending on the show and budget. And when this is the case, the production will make all necessary arrangements and cover all deposits and rental fees.

If your show has a travel or housing coordinator, he or she will probably have a list of local rentals. If you’re on your own when it comes to finding housing, then you’re going to want to contact rental agents and brokers in the area. If you’re going to be needing the rental for a long period of time, you can usually negotiate a more favorable rate than someone just renting for a couple of weeks or a month. The film commission office should be able to give you the names and numbers of local rental agencies.

It should be mandatory for those who choose to make their own living arrangements to inform the production office of where they’re staying, and if not reachable on a cell phone, how they can be reached. Although some people prefer to keep this information confidential, it should be made clear that it’s for emergency purposes only (like in the event of an evacuation).

Thanks to my pal, Mimi McGreal, for fine-tuning this chapter for me.

FORMS IN THIS CHAPTER

• Travel Movement — primarily used when many (or all) members of a shooting company are scheduled to travel at the same time

• Quick Reference Travel Movement — used to track any number of individuals traveling to any location

• Individual Travel Itinerary

• Hotel Room Log

• Hotel Room List

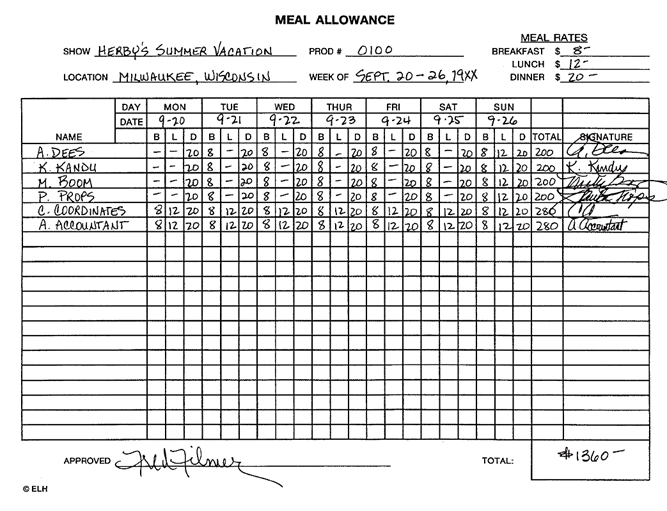

• Meal Allowance — form used for individuals signing for their per diem