Chapter 6

Pre–Production

WHAT IS PRE–PRODUCTION?

You’ve been successful in raising independent financing for your picture or the studio, network or cable network has given you a green light on your project, and you’re ready to start pre–production. Pre–production is the period of time used to plan and prepare for the shooting and completion of your film. It’s the time in which to:

• Produce a final script

• Schedule and budget your show

• Locate and set up production offices

• Hire a staff and crew

• Cast the film

• Meet with department heads, get realistic cost estimates, refine the budget and make sure your film can be done for the amount of money it’s budgeted for

• Have the script researched and all necessary clearances secured

• Evaluate locations, visual effects, special effects and stunt requirements as per your script

• Arrange for insurance and a completion bond (if necessary)

• Become signatory to the unions and guilds you wish to sign with and post any necessary bonds

• Scout and choose locations

• Contact film commissions for distant location options

• Book travel and hotel accommodations

• Secure passports, work visas, a shipper, customs broker and all necessary permits if shooting out of the country

• Build and decorate sets

• Wardrobe actors and have them fitted for wigs and prosthetics (as necessary)

• Have the director read through and talk through the script with the actors, and if possible, rehearse

• Take pre–production stills and shoot pre–production videos

• Teach and rehearse dance and/or fight routines, practice on–screen skills such as horseback riding or piano playing

• Negotiate deals with vendors, and order film, equipment, vehicles and catering

• Prepare all agreements, releases, contracts and paperwork

• Plan stunt work, aerial work and special effects

• Line up special requirements, such as picture vehicles, animals, mock–ups, boats, helicopters, models, etc.

• Set up accounts with labs; set up editing rooms; schedule t e routing of dailies; plan a post production schedule; hire a post production crew; and pre–book scoring, looping and dubbing facilities

• Clear copyrighted music/video/computer playback you wish to use in your picture

ESTABLISHING COMPANY POLICIES

Whether you’re opening a temporary production office for the purpose of working on one show or you’re part of an established production company that produces several shows a year, each production should operate under an established set of policy guidelines and basic operating procedures. Establishing well–defined office procedures will not only help you avoid unnecessary delays in disseminating information and paperwork, but will also enable you to maintain a more organized, more efficient production office that’s better able to meet the needs of the entire shooting company. It’s important for staff and crew members to know, coming in, what the company’s policies are, what’s expected of them and what they’re specifically responsible for.

Most production companies distribute policy memos to all new crew members by attaching them to deal memos and/or start paperwork packages, integrating the acceptance of these rules as a condition of employment. In fact, the memo is sometimes called The Rules of the Game.

Descriptions of the types of policies can be found in Chapters 2 and Chapter 3, but here’s a list of the topics that should be included in an informational–rulesprocedures memo:

• Basic production office information: address, phone and fax numbers, security info, where to park, etc.

• Payroll, paychecks and timecards

• Opening vendor accounts

• Purchase orders

• Check requests

• Petty cash and reimbursable expenses

• Competitive bids

• Use of personal vehicles

• Auto allowances and mileage reimbursement

• Box rentals and computer rentals

• Cell phone reimbursement

• Confidentiality

Along with The Rules of the Game, deal memo, and start paperwork package, it’s a good idea to include a copies of:

• The Filmmaker’s Code of Conduct (see Chapter 18)

• Copies of safety bulletins appropriate to your show and an Acknowledgment of Safety Guidelines form (see Chapter 17), to be signed by each employee

• Environmental guidelines (see Chapter 31)

• A copy of the company’s policies on Sexual Harassment (see Chapter 17)

• A copy of the company’s Standards of Business Conduct (see Chapter 9)

STAGES

If you’re not going to be exclusively shooting exteriors and practical locations, one of the very first items on your pre–production to–do list should be the securing of stage space. Except for a handful of TV shows that shoot on their home lot (occupying a standing stage at a network), you have three basic choices: a warehouse, a sound stage on an independent studio lot or a sound stage at a major studio lot. In the Los Angeles area, the majors that most commonly rent sound stages and/or offices to outside productions are Paramount, Sony and Universal. Others (like Warner Brothers and Twentieth Century Fox) tend to fill up with their own productions.

Costs and services vary widely among the independent lots, and you’ll find more of them springing up all the time as lucrative incentive programs continue to lure production to more states and countries. Some of the larger independent studios in Southern California alone include Raleigh/ Manhattan Beach (with 14 stages), Culver Studios (with 13 stages), Raleigh/Hollywood (with 12 stages) and Sunset–Gower (with 12 stages). Some other well–recognized studios include Raleigh in Baton Rouge and Budapest; EUE Screen Gems Studios in Wilmington, North Carolina; Albuquerque Studios in New Mexico; and the impressive new Filmport Studios in Toronto. Smaller stage facilities are available in just about every major city and are used primarily for commercials and smaller, local shows.

Warehouse space can be found in just about any city – often available for short–term rentals at reasonable prices. Warehouses can be used for stage space, to build sets, as a staging area, to accommodate the art department, as set dec and property offices, for lock–up areas or any combination of the above. Some even come with enough adjoining office space to run an entire show out of. Not quite a warehouse, but a show I did several years ago that was based out of an old airplane hangar. It didn’t have quite enough offices, but we brought in mobile office trailers to supplement our needs. I worked out of mobile offices on another show as well, and on this one, we were parked outside of an ice arena. So I use the term “warehouse” lightly, because you’ll find that other large, open, enclosed spaces will often work just as well – as long as the amenities are sufficient.

On my list of warehouse must–haves is work space that is sufficiently sound (no holes in the walls or collapsing ceilings), clean (or can be cleaned), has adequate and decent bathroom facilities and is free of bugs and other critters. You’ll want to make sure that any noise from the surrounding area isn’t going to interfere with your activities (for instance, you don’t want to be shooting in a building that’s located near an airport, fire station or freeway if the building isn’t soundproof), and that the light and/or noise created from your activities inside and outside of the warehouse won’t be a problem for those living and working around the warehouse nor a violation of any local ordinance. Consider whether the warehouse has enough uninterrupted floor space, enough power and air conditioning. Does it have a metal roof that could cause sound problems or concrete floors that can complicate construction? And can the rafter/joists accommodate the weight of heavy lights (or would you have to bring in truss or light from the floor)?

You’ll need plenty of parking, warehouse doors that are wide enough to accommodate trucks and heavy equipment being driven into the warehouse, ceilings that are high enough (at least 18–20 feet) and sufficient electrical wiring. Also consider your security needs.

When it comes to studio lots, some shows will base their entire production on the lot utilizing both stages and offices. Sometimes, you’ll just need a stage or possibly a stage and a couple of offices. Your needs will vary from show to show.

Whether it’s a major studio or independent, though, once on a lot, your stage deal will either come with (or you can negotiate the inclusion of) services and amenities such as security, dressing rooms, offices, furniture, phones, power, access to the lot’s medical department, commissary, etc. So if you have a choice, weigh the extras you’d have to pay for separately when shooting at a warehouse with what might already be included in a studio deal.

Episodic television shows that are headquartered on lots for extended periods of time are more apt to work out package deals. Features (that might not be there for as long and/or shoot part of their film on location) are more likely to pay for various lot services on an à la carte basis. Generally, however, the longer you’re planning to be on a lot and the more you’re able to pay, the more you’ll get. And as there’s usually a greater demand for office space than a studio can accommodate, it’s the shows that are going to be there the longest, use the most services and make the most comprehensive package deals that get first dibs on the offices. So you’ll need to know coming in how much stage space you’ll need, for what length of time, how much of the show will be done on the lot and what studio services you’ll be using.

The beauty of being on a lot is that you’re paying for the convenience of one–stop shopping, as many of the larger studios have a special effects shop (meaning, you’d only pay for the time needed opposed to keeping your effects guy’s shop on rental for the run of the show), post production facilities, screening rooms, hardware, construction, a sign shop, graphic design, property, wardrobe, commissary, etc. And these are services you would pay for only as needed.

When on a studio lot, you’ll typically be billed for power, heating and air conditioning, parking, security and telecommunications. And you’re more often than not required to use the studio’s grip and electric equipment. Some will require you to use their grip and electric equipment only when shooting on the lot; others will require that you use the equipment throughout your shoot, even when shooting on location.

If a studio has a commissary, and you break your cast and crew for lunch, there’s no need to bring in a caterer. Besides, some lots won’t let you bring in outside caterers anyway. There are exceptions, of course, and what some will do is let you bring in your own caterer but impose a surcharge for allowing you to do so.

Studios create standard rates for use of their stages and other facilities and services, but some studio administrators will be flexible, depending on supply and demand. If you call when the industry/town is busy and there’s a high demand for stage space, your chance of getting a break at a major lot will be slim. If you call at just the right time, however, maybe during the holidays or during the TV hiatus period when business is slow, or maybe when someone has just canceled a stage and the next tenants aren’t due for another month or two – leaving an immediate vacancy – then you have a decent chance of making a good deal. It’s definitely worth the call to find out.

Most studio deals are negotiable. And although stage costs will vary, expect one cost per day for prep and strike days and a higher rate for pre–light and shoot days. Also anticipate the added expense of a studio–provided production services representative or stage manager and possibly studio grip and electric best boys, in addition to your regular crew.

For the studio management, it’s not just about making money but also about building relationships. Maybe you’ll be offered a break on a stage when doing your first small, independent film, but it’s on the chance that eventually, you’ll bring a larger–budgeted film to the studio and be able to pay the going rate. It’s also important for you to maintain a good relationship with the studio’s facilities management, so when you run into a problem or there’s a change in your schedule, they’ll work with you to solve your problems together.

As soon as you even think you’re going to need stage space, even if it’s not going to be for a while or your shooting schedule hasn’t been finalized yet – place a hold on a stage (or stages) as soon as possible. (It’s not unusual for producers and UPMs to put holds on stages at more than one studio.) There’s no charge to place a hold on a stage, and you can always let them go, but it could be difficult to get one at the last minute. Stay in touch with the studio’s facilities manager or head of operations, and release the stage(s) as soon as you know you don’t need it/them. During busy times, there are often second, third and fourth holds on any given stage. Say the third hold is ready to commit, then the studio will call the company with the first hold and then the second (if the first isn’t ready to commit). If neither are ready, then the stage will go to the company with the third hold – the one ready to write the check, sign a contract, submit a certificate of insurance and take possession.

A few words of warning, though – before you sign on the dotted line, know exactly what you’re getting and what you’re paying for. Know how the studio works, what they offer, what on–lot equipment or services you’ll be required to use and what may be required of your crew (things relating to air quality standards, environmental guidelines, safety requirements and the disposal of haz–mat materials). You don’t want any surprises later on.

Review the studio contract to make sure it that reflects what you agreed upon, and have your project attorney review it as well. If the contract states that you’ll be receiving a certain level of amps on the stage, find out from your DP if that’s enough. Find out how long it’ll take to have your phones programmed and working? How many parking spaces will you be given near your stage? Get a map of the studio and a list of lot extensions. And if you have any questions – ask.

MEETINGS, MEETINGS, AND MORE MEETINGS

Pre–production is filled with meetings – one after another. Expect any number or combination of the following:

• If you’re working on a project for a studio, network or major production company, sometimes that studio/ network/company will invite key personnel from your show to attend a Start of Production meeting, which is an opportunity for you (and those from the production invited to attend) to meet the individuals you’ll be dealing with throughout the production. Representing the studio/network/company may be representatives from the departments of business affairs, legal, labor relations, finance, casting, insurance, research, music, post production, facilities, transportation, publicity, product placement, etc.

• A Look of the Film meeting is set up early, during preproduction, and is generally attended by the producer, director, production designer, DP, costume designer and possibly the editor and a production executive or two.

• The producer, director, line producer/UPM, production coordinator, production designer, art director and art department coordinator will usually meet to discuss Clearances once the script has been researched and an initial clearance report has been issued. Attending the meeting may be an in–house Clearance Department representative or an individual representing an outside clearance company. The clearance report will indicate what can be cleared for a price (how much that price might be) and what can’t be cleared. This is also the time to discuss and present alternative names, logos, film clips, magazine covers, artwork, etc. And based on the latest script changes or design concepts, new items the production wishes to have cleared are discussed. The art department coordinator is the one who usually works with the clearance person/company on a day–to–day basis, and if there is no art department on your show, then it would be the production coordipment, nator. Following this initial meeting, progress reports are periodically issued indicating clearance updates, and a final report is issued once all clearance issues have been resolved.

• Most shows hold a Product Placement meeting attended by a product placement rep and the producer, director, line producer/UPM, production coordinator, production designer, art director, art department coordinator, set decorator and lead person, property master and assistant property master, costume designer and supervisor, transportation coordinator and captain. During this meeting, a product placement wish list is presented, and the product placement rep will respond with what he thinks he can get for the show. After this initial meeting, expect periodic progress reports until all that can be placed on the show has been. And once again, the art department coordinator is usually the point person for product placement.

• Many films hold their first Marketing meeting during pre–production. Veteran producer Neal Moritz insists that you never want to make a movie without knowing what the poster and a 30–second trailer is going to look like. Attending these meetings would be the producer, director, studio execs (including those from Marketing and Publicity) and your unit publicist.

• Budget meetings occur throughout pre–production. The producer, line producer, UPM and production accountant meet often to revise the original budget and shift dollars from one account to another as new decisions are made, locations are locked down, crew deals are finalized, cast deals are made, script changes are integrated and minds are changed. And individual departmental budgets are refined as logistics fall into place. These meetings continue to take place until shortly before the start of principal photography, when supposedly everything is locked down and a final budget is approved. That’s how it works in theory, but actuality, the budget (although final) continues evolve as more script changes are approved, shooting runs behind or ahead of schedule, insurance claims occur, certain costs are higher than anticipated and unexpected events affect costs. So in reality, the budget meetings never stop, but at a certain point, are somewhat limited to weekly Cost Report meetings.

• Expect at least one visit from an in–house, studio or network safety executive to discuss safety guidelines. The Safety meetings would be held with various departments including grip, electric, special effects, construction, stunts, transportation, the ADs and the UPM and production coordinator. Most studios and production companies will provide separate binders or folders full of safety guidelines tailored to each department, and discussions will cover such topics as use of protective safety gear, operating heavy equipment, working with and disposing of hazardous materials, working around water, work around helicopters and whatever else might be pertinent to your production.

Whether it’s an in–house safety person or a risk control specialist from the insurance company, expect them to schedule meetings with stunt and effects personnel to discuss the steps to be taken to diminish the risk of accidents and injuries occurring during the execution of stunts and effects.

• Also expect an Insurance meeting with your production staff, risk manager and/or insurance broker. You’ll discuss cast exams, the issuing of certificates of insurance, special coverages, deductibles, claim reporting procedures and general insurance guidelines.

• If you’re working on a studio or network show, don’t be surprised if you’re invited to a Anti–Discrimination and Sexual Harassment seminar. In some instances, the production may be expected to set this meeting up and to pay for all costs associated with it the presentation itself, the rental of the room and refreshments. Crew members who haven’t started yet may even have to be put on payroll simply to attend this meeting.

• A Prop meeting is like a grown–up version of show–andtell. The property master and assistant property master will bring in a range of items for the director and producer to look at, allowing them to select the props they want to use. Show–and–tells regularly occur throughout pre–production with other aspects of the production, such as sets, costumes, picture vehicles, cast trailers, logos and signs, mockups and effects.

• If you’re going to be shooting on a distant or foreign location, it’s a good idea for the shipping and/or production coordinator as well as a representative from your shipping company to hold a Shipping meeting with at least one representative from each department. This way, procedures can be laid out, everyone’s needs can be addressed and all questions answered.

• Some studios and production companies will set up an Asset Management meeting with production staff, the costume supervisor, property master and set decorator to discuss which costumes, props and pieces of set dressing are to be tagged (in advance) to save for possible reshoots, publicity, marketing and/or archival purposes.

• Production meetings are the most common of all meetings held during pre–production, and although two would be helpful, there’s always at least one full production meeting held the week before the beginning of principal photography. In attendance will be one or two key people from each department. It’s a big one, so you’ll need a big conference room or possibly an area of a stage. The meeting usually starts first thing in the morning (with a continental breakfast set out for those attending), and it’s not unusual for it to last until lunch. If a full shooting schedule hasn’t yet been distributed, it’s done so at this meeting, and the first assistant director will verbally go through the entire schedule – allowing each department to address their concerns and questions and for final issues to be discussed and decisions made. Studio, network and/or production company executives may also attend to address issues such as safety, insurance, music, etc.

COMMUNICATIONS

Long gone are the days when we had to keep change on hand for pay phones. Evolving technology has not only advanced communications by light years, but continues to do so – never ceasing to amaze me with the latest tools and toys that don’t take long to become standards in our industry. Significant changes in the past several years have included digital phone systems in the office, wireless Internet routers, more hand–held mobile devices than I can count, protected subscription–based websites that provide the information and documentation we need (call sheets, production reports, etc.) relating to our production and satellite systems that allow us to use phones, faxes and the Internet in the most remote locations imaginable. We never had to think about these things before, but now unless you’re incredibly technologically savvy, not only do you need a techie on your staff, but there’s a good chance you’ll also have to at least consult with IT and telecommunications experts. Entire companies have sprung up that do nothing but create communication systems for film productions – whether it’s setting up a phone system for you in the office or setting up large satellite dishes around your set. And whenever new technology is introduced that has the power to make our jobs easier, I guarantee you, our industry will be among the first to have it.

Cellular Phones, BlackBerrys, Wireless Internet and More

On some shows, it’s not unusual for everyone to be expected to use their own cell phones and then get reimbursed for business–related usage (or sometimes, unfortunately not). Depending on your location, the features needed and if the production can afford it – the production may decide to rent phones for the crew to use – whether the show is being shot locally or on location. There are a few companies that cater to the entertainment industry by renting cellular phones, Nextels, BlackBerrys, wireless Internet products, walkie–talkies and other communications equipment on a monthly basis, so you don’t have to purchase equipment or sign long–term contracts.

Ordering cell phones is fairly simple once you’ve established a few basics. One thing your vendor will need to know is where your production is going to be using the phones (your locations). Once they have this information, they can recommend a carrier and secure local phone numbers for you with the area code and prefix of the city and state where you’ll be shooting. They can also suggest phones and calling plans for your production (and budget), but will first need some information – like whether the phones will be used to make domestic or international calls. Will you be traveling internationally? What features would you like the phones to have? Based on that information, they can provide phones that call or work worldwide or satellite phones that will work virtually anywhere.

A couple of years ago, I was on a show, and we rented phones that had the capacity to text, but we hadn’t stopped to consider adding a texting option to our calling plans. Talk about running up the bill! This oversight resulted in exorbitant text charges and a hard–learned lesson. But things have changed significantly since then. Texting is more popular then ever, and it’s a practical way for the crew to communicate. So if you anticipate your crew utilizing this feature, you can now easily add a reasonably priced texting plan. If you don’t, then you’ll have the same problem I did – costs that add up quickly. Text plans are currently available from 200 texts per month to unlimited texts, including picture messaging.

Once you decide that you’ll be renting phones, you’ll need to decide who it is you want to give a production phone to (based on their need to communicate with vendors, their department, the office, the set, etc.) and when they’re to receive it. And as it stands to reason, the list of names will grow as you move farther away from your home base. As for the cast – lead actors and their assistants will often be given production phones as well as wireless Internet in their trailers (or dressing rooms) as part of their perk package.

Selecting calling plans has gotten much easier lately, and now instead of multiple options, there are basically two: shared minute plans and unlimited calling plans, and there’s not much cost difference between the two. Shared does cost a little less but leaves some exposure to overage minutes. Unlimited talk and unlimited text eliminate any possibility of overages or surprises. (Note that texting plans don’t cover the cost of specialty ringtones, but that feature can be blocked.)

Those people/departments who tend to use the most minutes will include the producer, line producer, UPM, second assistant director, key set PA, camera loader, costume supervisor, the location department, transportation department, construction department, set dec and props.

For those approved to receive a BlackBerry or iPhone, the process is fairly simple. If you would like your vendor to sync up users’ e–mail with the unit prior to receiving the BlackBerry or iPhone, you just have to supply the vendor with their e–mail addresses and passwords. The users can also sync up their own e–mail accounts once they receive the devices.

Give your vendor at least one full day of lead time to secure the necessary phone numbers and take care of any programming. And speaking of programming, they can take the list of everyone on your show (receiving a phone) and input their names and numbers into each phone for instant dialing. When the phones arrive, they should be in a carrying case that includes a wall charger, car charger and an extra battery. Some cellular packages might also include a hands–free device to use while driving.

Another “can’t live without” feature in the world of on–set and location communications is broadband wireless Internet access. There are currently two popular options: portable Wi–Fi units – or “hotspots” that provide Internet access via an Ethernet port or Wi–Fi within a 50–to 300–foot radius of the device. Up to 15 people can share the Wi–Fi connection at one time. And the Wi–Fi device can be password–protected to limit the number of users. The second type is a wireless USB card, which plugs directly into an individual user’s laptop. This unit gives the user greater portability but restricts usage to the laptop it’s attached to. Both the Wi–Fi hotspot and the individual USB wireless card will provide download speeds as high as 12 Mbps (megabits per second) and upload speeds as high as 5 Mbps.

One last thought about renting this equipment that we’ve become so dependent on is the constant attempt to keep the monthly bill at a reasonable level. Because this is one area that can so easily get out of hand, don’t hand out any mobile device lightly. They should only go to those who need them or possibly to departments where one or two phones can be shared. My other suggestion is to issue a memo to each individual receiving a device letting them know exactly what their calling plan includes (such as how many minutes, texts and amount of data). Additionally, those not on an unlimited plan should be advised that any additional charges they incur, if not pre–approved or verifiable as work–related, will be charged back to them. The word that comes to mind here is “vigilance.”

If you have any questions about the latest in cellular devices, smartphones, wireless Internet products or satellite phones, feel free to contact my favorite cellular vendor Brian Bell at Airwaves Cellular in Sherman Oaks, California. Airwaves has been around for over 16 years, and they’re experts at providing communications equipment to productions throughout the world.

Walkie–Talkies

Your assistant directors will tell you how many walkie–talkies (or just “walkies”) they anticipate needing, but the UPM will make the final determination as to how many are ordered. It’s not unusual for a moderately budgeted show ($4–$6 million) to use 50–60 walkies during principal photography. At least one radio will be assigned to most departments working on or around the set, with some (like Transportation) receiving several more. Besides the producer, director and line producer/UPM, all assistant directors and set PAs will have one.

Develop a relationship with a vendor that specializes in RF (radio frequency) equipment and has the technical knowledge to assist you with all of your needs. Companies that carry a lot of other items as well as walkie–talkies might not be able to offer you a sufficient selection of models and accessories, and what they do offer may not be what’s best for your production. Use a company that has several model options, not just one, and stick with authorized Motorola dealers. Also, don’t go for the least expensive model, because the lowest price is rarely the best deal. Bottom–of–the–line models don’t perform and don’t last as well as the others, and you’re bound to exhaust any savings with loss and damage (L&D) charges.

Your walkie vendor will want to know as much about where you’re going to be shooting as possible in order to recommend the equipment that will best suit your locations. He’ll want to know how much of your schedule you’ll be shooting on a stage or indoors, and when outside, what the terrain is like and what type of weather you expect to encounter.

The current standard for our industry is to use walkie–talkies with 16 channels. VHF (very high frequency) radios with 5 watts of power work best across open spaces. UHF (ultra high frequency) radios with 4 watts of power are better at penetrating structures and high terrain and are more reliable in bad weather. So knowing where you’ll be shooting will allow your vendor to recommend the radios that will work the best at your locations.

When shooting in particularly challenging terrain, to increase your signal and range, a repeater or a pair of base stations might be called for. A repeater is a one–channel high–powered relay. The only drawback here is that repeaters have to be ordered when your walkies are ordered. It’s not something you can decide to get later on, because all of the radios have to be programmed to the repeater. Base stations are also 35 watts of power, you can order them at any time, and they carry all 16 channels. You talk directly into base stations, and they function as high–powered radios.

The walkies will be programmed before they’re shipped or you pick them up. The vendor has the appropriate software, computer setup and adapter – a system that precludes their customers from programming their own radios. And they program them using safe frequencies – ones that aren’t being used by law enforcement, safety, military or other agencies or organizations.

Accessories

• Chargers: There are bank chargers (that hold up to six radios) and individual chargers. No matter which you use, make sure the ones you’re getting are high–speed, rapid–rack chargers that will charge the radios in about an hour.

• Headsets: There are several types of headsets. You’ve got ones that are noise–canceling, a light–weight model with a small boom that comes out in front of the ear, an ultra–light model that fits into the ear and has a boom that runs along your jaw. There are the ever–popular surveillance kits with ear buds, mics built into the cord and a clip that attaches to your shirt. Other surveillance kits have a clear acoustic plastic tube, with the ear bud hanging from the tube. There are also hand mics that sit on the end of a coil and clip onto a shirt on your shoulder, close to your ear. This is a preferred model with grips and electricians who work in noisy areas of the set.

Headsets, especially surveillance kits, are a highly debated accessory, as they tend to frequently disappear. Some production companies will no longer rent surveillance kits, and others will make individual crew members responsible for the cost of a missing headset. I’ve experienced the phenomenon first–hand and have never figured out why so many crew members feel entitled to take headsets home or why they’re so easy to lose. And more than once, I’ve seen an older model headset returned in the place of a brand–new surveillance kit – allowing the perpetrators to trade up.

At the end of the chapter, you’ll find a sign–out sheet for walkies and accessories. Make sure that each person receiving a radio or accessory has to personally sign for the equipment he or she is given, and firmly let them know that you expect to have the equipment returned at the end of the shoot.

• Vendors that specialize in walkies may also carry bullhorns, Nextels and national pagers. Many of them also carry protective waterproof bags (which are generally purchased, but occasionally can be rented) that fit over the radios and help shield them from damage caused by rain or other inclement weather. Something else I’ve learned the hard way is that moist, windy, dusty air creates mud that finds its way into radio circuits, which equals a lot of L&D. So depending on where you’ll be shooting, it might pay for you to look into these bags.

If you can’t find a company that specializes in walkies and other RF equipment in your area, use one from a major production center like Los Angeles, because they’re used to shipping their equipment all over the world.

And one last piece of advice from my pal Gary at J&R Productions, who helped me with this section, and that is to treat your walkie like you would your cell phone. They’re just as easily likely to succumb to dirt, moisture and falling on the ground.

Note: J&R is located in Burbank, California, and is a major supplier of walkie–talkies and other radio frequency equipment in our industry.

PREVISUALIZATION

I started working on Tropic Thunder in February 2007, and after having taken some time off, it was the first big feature I had worked on in quite a while. As I was settling in, I kept hearing the term previz. Then I was asked to allocate an office for the previz guys and just kept wondering, “What’s previz?” Where had I been? I didn’t think I’d been away that long. Wasn’t I the one who had written a book about what goes on in a production office? Maybe not all shows use previz? But then I finally met the previz team. They were from a company called Proof, and as I stood over them watching them create what looked like electronic storyboards on their computers, I finally asked them to please explain the process. Aha! More new technology to make our jobs easier – how wonderful. Only this technology had been around for a while, and I’d just never been exposed to it.

Previz doesn’t replace storyboards, but acts more as an adjunct to storyboards, as previz artists provide 3D animation tools to help design and plan shots. Taking into consideration all of the elements required to complete a sequence (location, actors, surrounding buildings, props, vehicles, action, etc.), they construct a 3D video game version of the sequence, complete with details such as lighting, lenses, and camera angles. Seeing what the actual shots are likely to look like gives filmmakers the chance to make changes and solve potential problems during pre–production.

Wikipedia defines previsualization as a technique that attempts to visualize scenes in a movie before filming begins. It further explains that the advantage of previsualization is that it allows directors to experiment with different staging and art direction options – such as lighting, camera placement and movement, stage direction and editing – without having to incur the costs of actual production. Previsualizations can include music, sound effects and dialogue to closely emulate the look of fully produced and edited sequences, and are usually employed for complex or difficult scenes that involve stunts and special effects.

In an October 11, 2005, article on previsualization entitled “Whiz–bang Viz!,” Debra Kaufman explains:

The process, called “previsualization,” or previz, is storyboarding taken to the next level: digital storyboarding with a certain degree of interactivity. Creatively, it allows a filmmaker to completely rough out a movie using the same lighting, camera angle and effects parameters as would be employed in the finished film. Essentially, it’s a blueprint of the film but one created in a cost–effective environment where the whole point is experimentation, and changes can be made and viewed on the fly.

The previsualization footage created by the team from Proof was eventually handed over to the show’s editor to cut into sequences, and the assistant production coordinator received previz pages to photocopy and distribute to certain members of the crew. I was so impressed that I invited Ron Frankel, president of Proof, to guest–speak at my USC class so that I could expose my students to the process and to the new career opportunities this field presents.

Although utilizing the services of previz artists and modelers isn’t going to break the bank on larger–budgeted shows, low–budget projects might find it an extravagance they can’t afford. But before you dismiss it outright, call companies that do previsualization to discuss your show with them, and do it early on during pre–production. You might discover that you can afford previz for one complicated sequence (or two).

PLAN AHEAD

Plan for cover sets should the weather turn bad while filming exteriors. Know where you can exchange or get additional equipment (or raw stock) if needed at any time of the day or night. Keep names, phone numbers and resumes of additional crew members in case you suddenly need an extra person or two. Line up alternative locations in case your first choice is not available.

The lower the budget, the more prep time you should have – even if you’re doing much of it yourself because you can’t afford to hire anyone else yet. Lower–budgeted films don’t have the luxury of extra time or money, so it’s essential to be as prepared as possible – especially on these types of projects. No matter what the budget, unexpected and unavoidable situations (resulting in delays and/or added costs) will always arise during the course of a production, so expect and avoid as much as possible in advance. Ironically, the films needing the most prep time are the ones that can least afford it. And although it’s common for independent producers to prepare as much as they can while waiting for their funding, they’re somewhat limited until they can officially hire key department heads and start spending money.

Many variables, such as budget and script requirements, will determine your pre–production schedule. The following is an example of what a reasonable schedule (barring any extraordinary circumstances) might look like based on a six–week shoot with a modest budget of $4 to $6 million.

An ideal pre–production schedule would allow one and one–half weeks of prep for each week of shooting. Accordingly, a six–week shoot should have a nine–week prep period. The following basic eight–week schedule, however, should be more than sufficient, as well as cost–effective. However, note that this schedule accommodates a local show, not one that would take more logistics to accommodate a project being filmed on a distant or foreign location.

SAMPLE PRE–PRODUCTION SCHEDULE

Week #1 (8 weeks to go)

Starting Crew

Producers

Director

Line Producer and/or Production Manager

Production Coordinator

Production Accountant

Location Manager

Casting Director

Secretary/Receptionist

Production Assistant #1

Note: This situation would work if you know who you want on your show from the start. If not, some of those listed above may have to start first, so they can interview and hire the others.

To Do

• Establish your company, if not done earlier

• Start filling out union/guild signatory papers

• Lock in production offices and all other work spaces, sign lease agreements, have phone system(s) installed (if necessary) ?C then move in and set up

• If applicable, fill out and submit an application for a Permit to Employ Minors

• Firm up insurance coverage

• Sign with a payroll company

• Begin casting

• Start scouting locations

• Start opening accounts with vendors

• Send your script out for a clearance report

Week #2 (7 weeks to go)

Starting Crew

Production Designer

Note: Some productions prefer that the production designer start at the same time as the location manager.

To Do

• If there’s a key song or two in the script, start music clearance procedures using either your attorney or a music clearance service to determine whether the rights are available and how much the sync license fees are for each piece of music

• Meet with person/department overseeing product placement, and start the process as soon as possible. (It takes time to get approvals and actually get the products in time, so that Props, Set Dec, etc. won’t have to make these purchases.)

• Start scheduling cast physicals

• Talk to animal handlers if necessary (it might take several weeks to select and train needed animals)

Week #3 (6 weeks to go)

Starting Crew

Art Director

Set Designer

Assistant Location Manager

First Assistant Director Costume Designer

Note: Some line producers will wait until a week before most of the cast has been set to start the costume designer and will budget some weekend work for the costume department, as much of the casting tends to be last–minute.

To Do

• Start talking to and getting bids from visual effects houses

Week #4 (5 weeks to go)

Starting Crew

Asst. Production Coordinator

Assistant Accountant

Costume Supervisor

Transportation Coordinator

Property Master

Set Decorator

Production Assistant #2

To Do

• Scouting as needed with location manager, director, producer, 1st AD, and production designer

Week #5 (4 weeks to go)

Starting Crew

Director of Photography

Costumer #1

Lead Person

Note: The DP’S employment during prep is commonly nonconsecutive.

To Do

• At the beginning of this week, have your first production meeting.

Note: Depending on script requirements, the production designer will request start dates for the construction coordinator and construction crew, but it’s up to the line producer or production manager to decide when they would start. The line producer or production manager will also determine start dates for the stunt coordinator and special effects crew.

Week #6 (3 weeks to go)

Starting Crew

Second Assistant Director

Transportation Captain

Assistant Property Master

Swing Crew

Background Coordinator (if there are big crowds or special requirements such as cheerleaders or athletes, they might have started sooner)

2nd Assistant Accountant and/or Payroll Accountant

To Do

• Camera tests

• Final budget review with each department

Week #7 (2 weeks to go)

Starting Crew

Script Supervisor

Key Grip

Gaffer

Hair Stylist

Costumer #2

Production Assistant #3

To Do

• Production Executive, Producer, Director and Production Designer make final changes to sets; locations; wardrobe; cast wigs and/or hair color; prosthetics; hero props; models; and anything else pertinent to the look of your show

• Tech scout with department heads, so equipment lists can be prepared, and the lists can go out to vendors for bids.

• Once vendors are selected, lease agreements should be approved by Legal and signed

• Lock in locations, make sure all permissions are secured and permits ordered

• Casting should almost be done

• Hair, Makeup and Wardrobe tests

• Finalize script

• Sign off on final budget

Week #8 (final week of prep)

Monday

Starting Crew

Set Production Assistant

Drivers (as needed)

Editor

Assistant Editor

Assistant Camera Crew

Unit Publicist (if applicable)

To Do

• Post SAG bond by this date (if needed), or you won’t be able to issue work calls or clear actors through Station 12

• Complete casting, prepare and send out actors’ contracts

• All applicable location agreements are signed and permits secured

• Order all equipment, vehicles, raw stock, expendables and catering

• Sometime this week, a cast read–through is usually scheduled

• Sometime this week, a rigging crew might start (if applicable)

• Sign off on stand–ins, photo doubles and stunt doubles

• Distribute final shooting schedule, one–line schedule, day–out–of–days, crew list and cast list

• Locations are prepped this week

• Rehearsals

• Start Editorial crew, and start setting up editing rooms

• Camera/Makeup/Wardrobe tests

Note: Talk to your caterer. Many of them will graciously supply the food for a “kick–off” party, read–through and/or production meeting at no charge.

Tuesday

To Do

• Hold final production meeting with all department heads (do it early this week, so there’s still time to take care of anything that might come up)

• Maps to all locations should be prepared

• Finalize arrangements for dailies

Wednesday

Starting Crew

More Drivers (as necessary)

To Do

• Director and DP may want to review locations and shot list

• Hair, Makeup and Wardrobe start loading trailers as needed

Thursday

Starting Crew

Best Boy, Electric (earlier, if prerigging)

To Do

• Members of the camera, grip and electric departments begin working at the equipment houses (earlier than Thursday, if necessary), checking out equipment and loading trucks

Friday

Starting Crew

Sound Mixer

Craft Service

Still Photographer

Video Assist

To Do

• Generate and distribute first day’s call sheet

• Give out cast calls

Those Who Start on the First Day of Principal Photography

Camera Operator

Boom Operator

Set Medic

Studio Teacher (if applicable – also might have started him or her sooner during rehearsals or to bank hours with minors if needed)

DAILY PREP SCHEDULES

I can’t overly stress the importance of publishing daily prep schedules. Unlike principal photography, in which all activities center around the set, during pre–production, members of the production team are scattered – scouting locations, having meetings, reading actors, working on script changes, working on the schedule or budget, etc. This is a time when good communication is essential and when everyone needs to be aware of everything else going on around them. The schedule is the best way to coordinate prep days. It keeps everyone informed as to exactly what’s happening each day, who’s attending each activity and when certain individuals are going to be available (so new meetings, scouts, casting sessions, etc. can be set up and choices evaluated by and with the people who need to be involved). Keeping an accurate daily schedule tends to enhance productivity and efficiency while decreasing confusion and duplication of efforts.

An updated schedule is usually distributed each morning – sometimes in the late afternoon as well. It can be done in a calendar format, or entries can be listed by day, date and times; and either way, the individuals attending each scheduled activity would be indicated. It works best when one person – usually the first assistant director or production coordinator – is designated to collect the pertinent information from everyone involved and coordinate the schedule. The schedule can change as often as two or three times a day, so anyone wanting to set up a meeting, for instance, would contact the designated schedule–keeper ahead of time to make sure that anyone else who should be attending the meeting is available. They would then confirm when the meeting is set, so it can officially be added to the Daily Schedule.

Here are the type of items that would be listed on a Prep Schedule:

• Location scouts

• Casting sessions

• Interviews with potential key crew positions

• Department heads’ first day of work

• Production meetings

• Script meetings

• Budget meetings

• Product placement meetings

• Stunt and/or effects meetings

• Extra casting meetings/stand-in interviews, extra casting sessions/interviews

• Picture car meetings

• Wardrobe fittings for lead actors

• Prosthetic fittings and molds

• Cast rehearsals and read-throughs

• (Lead) cast appointments for wig fittings and hair coloring

• Camera tests

• Hair, make-up and wardrobe tests

• Photo shoots

• Specific travel plans for cast members arriving in and out of town or for scouting parties traveling back and forth

• Publicity functions

• Pre-rigging

• Anything else that would be pertinent to your show

MORE ON LOGS AND SIGN–OUT SHEETS

Accounting tracks all assets – purchases made for the production worth at least $50 (some companies quantify an asset at $100) – but each department is responsible for monitoring its own assets, so they can be accounted for and checked against Accounting’s list at the completion of principal photography. You’ll find an Asset Inventory Log form at the end of this chapter that’s helpful for this purpose. It’s different than the Master Inventory form you’ll find in Chapter 29, which documents only the disposition of remaining assets being turned in at the end of the show – not counting those lost, damaged or sold.

The production coordinator or assistant coordinator keeps track of all items purchased for the office, which would include such things as: computer equipment, TVs, DVDs, etc. At the completion of principal photography, these items are turned in to the studio or parent company, stored or sold.

Equipment rented for the office should be kept track of as well, and for this, you’ll find an Equipment Rental Log form at the end of the chapter. This goes one step further than a Purchase Order Log, and when kept up, you’ll notice that returns are made and L&D charges are assessed and submitted in a more timely manner.

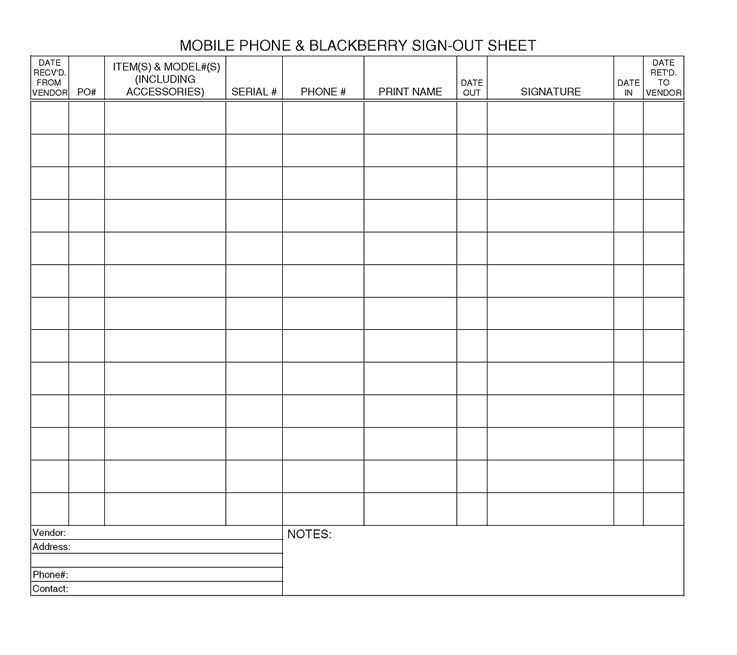

The production coordinator or assistant coordinator is also the designated distributor of mobile phones, Black–Berrys and (often) scripts, although sometimes the producer’s or director’s assistant will monitor the distribution of scripts. Walkie–talkies are traditionally handed out and collected by the second assistant director (2nd 2nd or DGA trainee). These sign–out sheets (also to be found at the end of the chapter) list the items, serial and/or unit numbers (if applicable), dates received and returned, department assigned to and a signature of the person being handed the phone/script/walkie.

DISTRIBUTION

There’s a staggering volume of information that must be dispersed to cast, crew, staff, studio, network, etc. on any given show, whether it’s in hard copy form, via e–mail or a dedicated website that authorized users can access. But no matter how it gets out, it all emanates from the production office, and its distribution is crucially time–sensitive. Not being able to get vital information out in time to those who need it will affect: pending approvals, deals, commitments, schedules, prep times and your budget. For instance, a casting director not receiving a revised day–out–of–days in time may result in a deal being made with an actor for a part that’s been shortened or no longer exists in the script. The background casting agency that didn’t receive a revised call sheet may have already given a next–day call to hundreds of extras who are no longer needed. An actor who doesn’t receive new script pages early enough may not have enough time to learn his new lines. Handing out shooting schedules, crew lists and call sheets may not seem like a big deal, but the entire production revolves around this data.

Because of the sheer magnitude of information disseminated and the number of people who must receive it, keeping a Distribution Log is the only way to ensure that everyone receives the information they need. A sample Distribution Log can be found at the end of the chapter.

Don’t assume that because you hang departmental envelopes in the production office and place copies of essential paperwork in the envelopes or leave copies of printed material in someone’s in–box, that it’ll be promptly retrieved. That goes for e–mails, faxes and phone messages as well. It’s your responsibility (or that of the person you designate) to make sure all essential paperwork and information gets distributed (and acknowledged) as soon as possible. That may involve tracking individuals down to verify that the information’s been received.

COLLECTING INFORMATION AND MAKING LISTS

Production offices generate massive amounts of paperwork in disseminating vital information to everyone involved with a film. Along with the schedules, day–out–of–days, location list, logs, purchase orders, sign–out sheets, script revisions, call sheets, production reports, maps, etc. – each show produces a Crew, Cast and Contact list, which are standard on every show. First drafts are produced during the earliest stages of pre–production and revisions are continually being published until the final drafts are issued at the completion of principal photography.

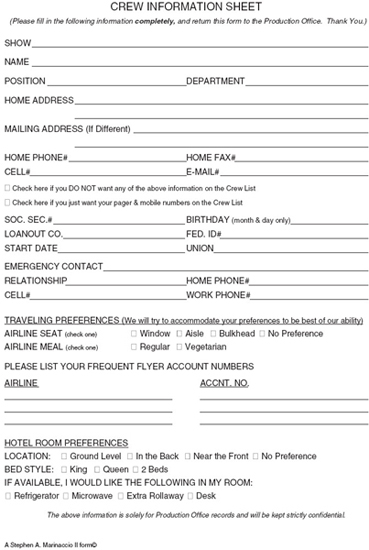

Crew Information Sheet

This is not a standard industry form, but it should be. Stephen Marinaccio introduced me to the Crew Information Sheet. These forms are distributed to cast, crew and staff with their start paperwork. Once completed, they’re kept in the production coordinator’s office, in a binder, in alphabetical order. Once completed, these forms contain all the information needed to create the crew list. Additionally, they provide an emergency contact and number for each person, which unfortunately, is occasionally needed and why it’s a good idea to send copies to your set medic. These forms also indicate birthdates (allowing you the opportunity to celebrate co–workers’ birthdays if desired) and travel and hotel preferences. Being able to make as many preferred arrangements as possible, in advance, minimizes a multitude of last–minute problems. Use the form found at the end of this chapter, or design one yourself that’s more specific to your show.

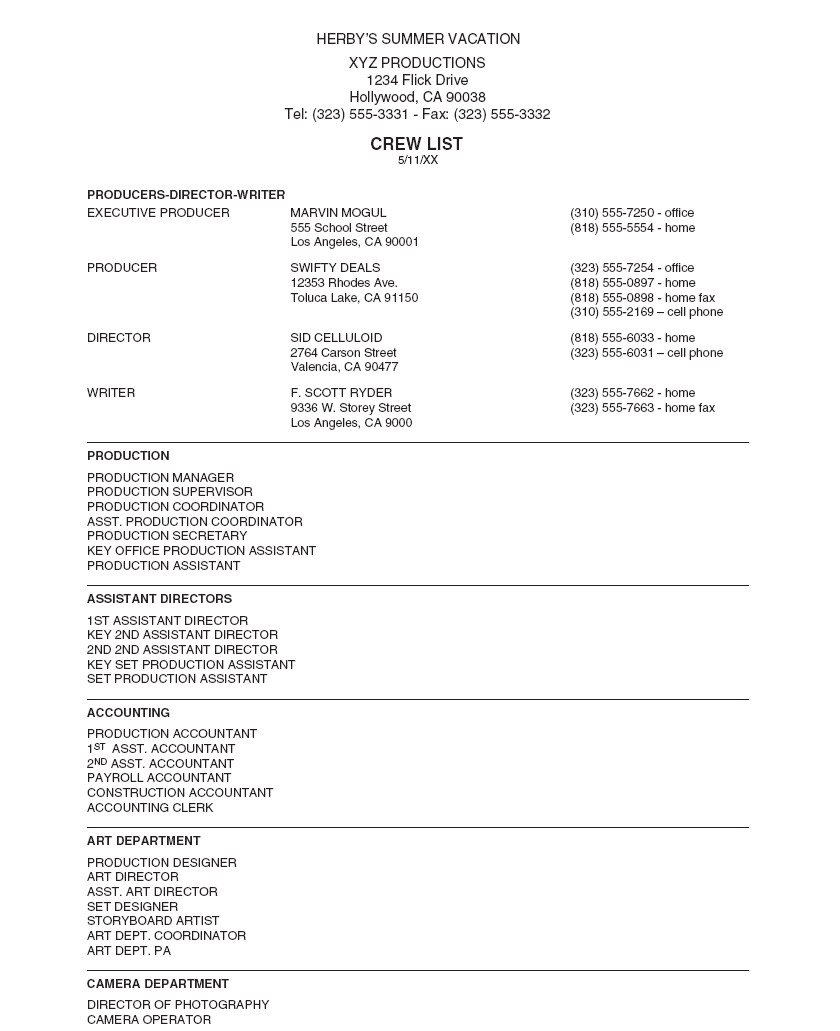

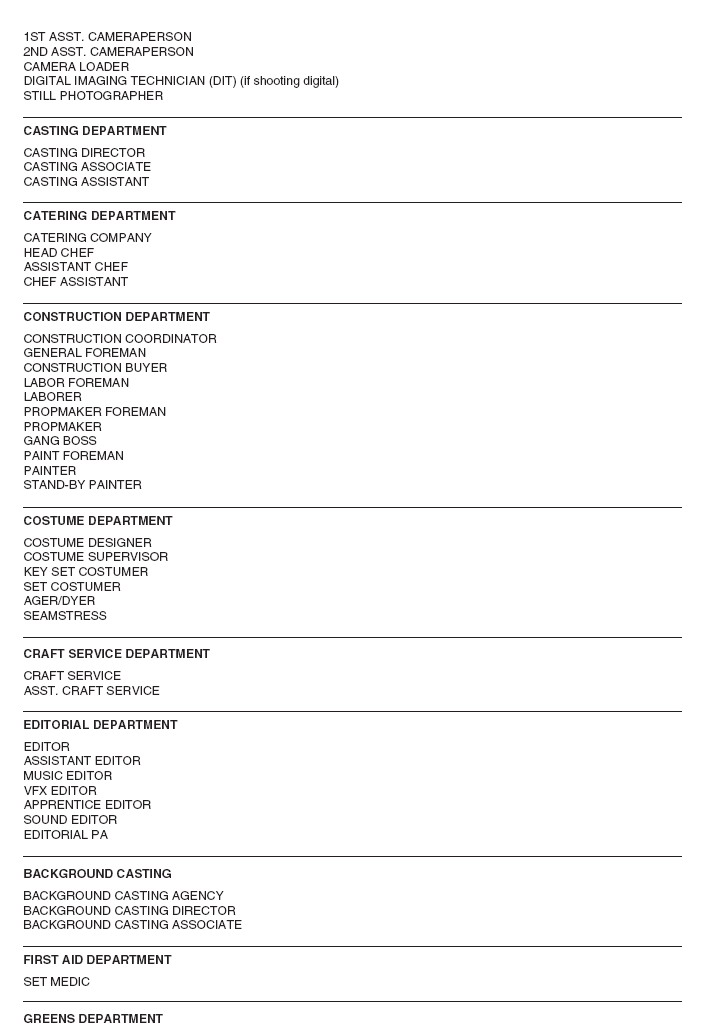

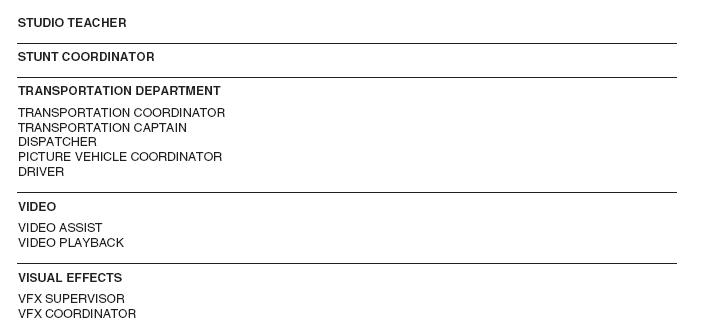

The Crew List

This is a listing of each member of the crew (by department) that includes their title, address, home phone number, home fax number (if they have one) and cell phone number. There are some people who prefer not to have their home address and phone number on the crew list, but there should be at least a cell phone number or an assistant referenced should this person need to be reached in an emergency. In addition to crew lists, many production offices also generate quick reference lists that just contain titles, names and cell phone numbers. Ahead you’ll find an example of what a crew list would look like. There’s no one format that’s universally used, but most are pretty similar. Also, some people make a cover sheet with an index, listing each department and the pages that department is listed on. The illustration indicates how names, addresses and all pertinent numbers are listed and then continues by department and position.

The Executive Staff List

Most shows are produced for a studio or parent production company, and you’ll be interacting with executives and individuals at that company on a daily basis. The studio, network or company will usually give you a staff list of in–house employees (pertinent to your project), and this list should be included at the back of your show’s crew list.

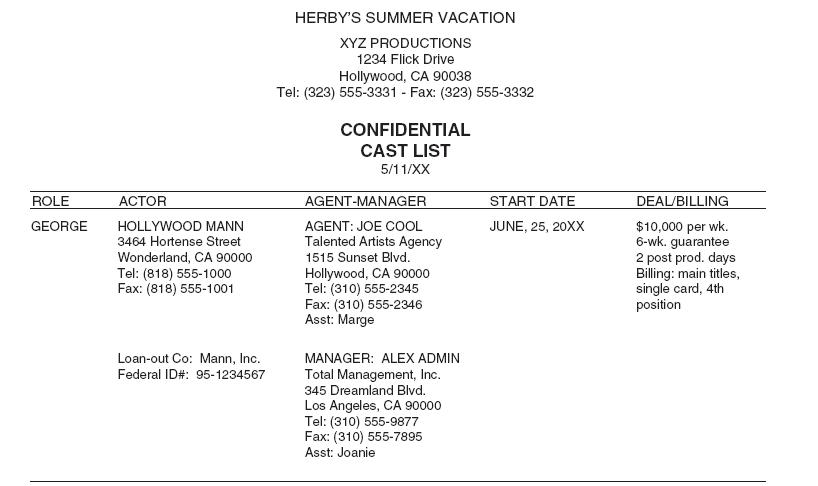

The Cast List

A basic cast list references each role, the actor portraying that role, and the contact information for their respective agents, managers and/or assistants. For years, it wasn’t uncommon for this list to also include the actors’ addresses and phone numbers, but due to privacy issues, the more personal information is reserved for the Confidential Cast List. The confidential version includes the actors’ home address and phone numbers and a brief synopsis of each of their deals.

Basic (bare–bones) cast lists should be distributed to a predetermined distribution list, including your costume, hair, makeup and transportation department heads. The confidential list is often goes to a select few: the producer, production manager, assistant directors, production coordinator, and production accountant. Actors’ deals are address and contact person for all pertinent vendors, not for general distribution.

FIGURE 6.1

As with crew lists, there is no one cast list format used by everyone; but they all end up looking fairly similar:

The Contact List

This Contact List – also known as a Vendor List – should include the name, address, phone/fax number, e–mail address and contact person for all pertinent vendors, including bank, insurance company, travel agent, equipment houses, courier service and/or shipping company, office furniture and supplies, lab, etc. If your production has various offices (locally and on location), they should be listed as well. The list is usually arranged in alphabetical order. Here’s a sample format along with possible contact list headings:

FIGURE 6.2

BETTER SAFE THAN SORRY

Even with the existence of industry safety guidelines and a location code of conduct, efforts must continually be made to be aware, cautious and thorough. Although this behavior will most certainly prevent many potential problems, be assured that no production company, regardless of size or stature, is totally immune from accidents, grievances, lawsuits and insurance claims. Be careful! It’s easy to get so busy on a shoot, that from time to time, a few small details fall between the cracks. And small details can quickly turn into big problems that come back to haunt you later on.

To best protect your backside, and that of the company, you should:

• Keep careful inventories and note when something is

• Put as much information on the back of the production report as possible, including the slightest scratch any one might receive. When a day passes and there are no injuries, indicate by noting “No injuries reported today” on the back of the production report.

• When someone is injured, complete a workers’ compensation (Employer’s Report of Injury) report as soon as possible, and get it to the insurance agency. Also attach a copy to the daily production report.

• Have an ambulance on the set on standby when you’re doing stunts that are even the least bit complicated or dangerous. Always know the location of the closest medical emergency facility (and post it on the call sheet every day).

• When you’re experiencing difficulties with a specific employee, keep a log detailing dates and incidents.

• Confirm all major decisions and commitments in writing; if an official agreement or contract isn’t drawn up, write a confirming memo detailing the arrangement.

• Don’t sign an agreement and contract until your attorney has reviewed it.

• Don’t sign a rental agreement for the use of equipment, motor homes, facilities, etc. until you or someone you trust can check out the quality of what’s being rented, and you know exactly what you are getting.

Favors involving any type of exchange are nice (i.e., the company uses a crew member’s car in a chase sequence in exchange for repairs to the car) but can also backfire on you. All such agreements should be backed up with a letter in writing stating the exact terms of the exchange and releasing the company from any further obligations.

PRE–PRODUCTION CHECKLIST

You have your script and your financing (or studio deal), and you’re ready to go. The following list will help you keep track of what you’ve done and what remains to be done.

Starting from Scratch

![]() Prepare a preliminary schedule and budget

Prepare a preliminary schedule and budget

![]() Find a good attorney who specializes in entertainment law

Find a good attorney who specializes in entertainment law

![]() Establish company structure (i.e., an LLC or partnership)

Establish company structure (i.e., an LLC or partnership)

![]() Obtain necessary business licenses from city, county and/or state

Obtain necessary business licenses from city, county and/or state

![]() Apply to the IRS for a Federal ID number

Apply to the IRS for a Federal ID number

![]() If you’ve established a corporation, get a corporate seal and minutes book

If you’ve established a corporation, get a corporate seal and minutes book

![]() Obtain workers’ compensation and general liability insurance

Obtain workers’ compensation and general liability insurance

![]() Sign all union and guild signatory papers (as applicable)

Sign all union and guild signatory papers (as applicable)

![]() Secure a completion bond (if applicable)

Secure a completion bond (if applicable)

![]() Open bank accounts (signature cards and corporate resolutions)

Open bank accounts (signature cards and corporate resolutions)

![]() Apply for all applicable incentive programs and/or tax subsidies (and complete any cultural test if required)

Apply for all applicable incentive programs and/or tax subsidies (and complete any cultural test if required)

![]() Find production offices and stage(s) as needed

Find production offices and stage(s) as needed

![]() Start lining up staff and crew

Start lining up staff and crew

Legal

Note: A production company’s legal or business affairs department or an outside entertainment attorney would routinely do this work.

![]() Secure the rights to the screenplay (literary purchase agreement)

Secure the rights to the screenplay (literary purchase agreement)

![]() Assignment of rights

Assignment of rights

![]() Distribution agreement

Distribution agreement

![]() Writers agreement

Writers agreement

![]() Life story rights agreements (if applicable)

Life story rights agreements (if applicable)

![]() Review all financing and distribution agreements

Review all financing and distribution agreements

![]() Sales agency agreement

Sales agency agreement

![]() Security interest documents and filings

Security interest documents and filings

![]() Loan documents (equity investors)

Loan documents (equity investors)

![]() Completion agreement

Completion agreement

![]() Interparty agreement

Interparty agreement

![]() Laboratory pledge holder agreement

Laboratory pledge holder agreement

![]() Laboratory access agreement

Laboratory access agreement

![]() Make sure script is registered with the WGA

Make sure script is registered with the WGA

![]() Negotiate (or review) and prepare the contract for the writer of the screenplay

Negotiate (or review) and prepare the contract for the writer of the screenplay

![]() Order all copyright and title reports

Order all copyright and title reports

![]() Prepare contracts for the producer, director, director of photography, production designer, casting director, costumer designer, co–producer, associate producer, line producer, composer and editor

Prepare contracts for the producer, director, director of photography, production designer, casting director, costumer designer, co–producer, associate producer, line producer, composer and editor

![]() Prepare minors’ contracts and all related documentation pertaining to the employment of minors

Prepare minors’ contracts and all related documentation pertaining to the employment of minors

![]() Review contracts regarding literary material to make sure all required payments are made

Review contracts regarding literary material to make sure all required payments are made

FIGURE 6.3

![]() Review permits and other documents having potential legal significance

Review permits and other documents having potential legal significance

![]() Prepare (or approve) all necessary release forms

Prepare (or approve) all necessary release forms

![]() Prepare contracts for principal cast

Prepare contracts for principal cast

![]() If applicable, prepare nudity riders

If applicable, prepare nudity riders

![]() Start music clearance procedures

Start music clearance procedures

![]() If not done by production, send script in to be researched, and secure all necessary clearances

If not done by production, send script in to be researched, and secure all necessary clearances

![]() Review all location agreements

Review all location agreements

![]() Review all rental and lease agreements

Review all rental and lease agreements

![]() As applicable, review contracts for digital effects, mechanical effects, creative and technical services and product placement

As applicable, review contracts for digital effects, mechanical effects, creative and technical services and product placement

![]() If applicable, handle all necessary requirements related to filming in a foreign country

If applicable, handle all necessary requirements related to filming in a foreign country

![]() If applicable, handle all immigration issues

If applicable, handle all immigration issues

Set Up Production Office

![]() Security, if needed

Security, if needed

![]() Furniture, including:

Furniture, including:

![]() Drafting tables and stools for the art department

Drafting tables and stools for the art department

![]() A safe for the accounting department

A safe for the accounting department

![]() Contact phone company for phone numbers and phone, fax and DSL lines

Contact phone company for phone numbers and phone, fax and DSL lines

![]() Arrange for a temporary phone system

Arrange for a temporary phone system

![]() Copier machine

Copier machine

![]() DVD/Monitor

DVD/Monitor

![]() Computers and printers

Computers and printers

![]() Production and accounting software programs

Production and accounting software programs

![]() Fax machine(s)

Fax machine(s)

![]() Office supplies

Office supplies

![]() Bottled water

Bottled water

![]() Coffee maker

Coffee maker

![]() Microwave oven

Microwave oven

![]() Refrigerator

Refrigerator

![]() Extra keys to the office (keep a list of who has keys)

Extra keys to the office (keep a list of who has keys)

![]() Cell phones for key personnel

Cell phones for key personnel

![]() Prepare and post departmental envelopes

Prepare and post departmental envelopes

![]() Prepare a restaurant menu book

Prepare a restaurant menu book

![]() Secure a cleaning service

Secure a cleaning service

![]() Establish an account with a courier/messenger service(s)

Establish an account with a courier/messenger service(s)

![]() Prepare logs for courier runs and FedEx shipments

Prepare logs for courier runs and FedEx shipments

![]() Prepare sign-out sheets for keys, scripts, etc.

Prepare sign-out sheets for keys, scripts, etc.

![]() Set up recycling receptacles and procedures

Set up recycling receptacles and procedures

Paperwork

![]() Have letterhead and business cards printed and distributed to those who need it (the art department will generally provide a logo/artwork)

Have letterhead and business cards printed and distributed to those who need it (the art department will generally provide a logo/artwork)

![]() Prepare fax cover sheets

Prepare fax cover sheets

![]() Prepare a map of how to get to the production office and/or stage

Prepare a map of how to get to the production office and/or stage

![]() Prepare a phone extension list to be placed next to each phone in the office

Prepare a phone extension list to be placed next to each phone in the office

![]() Set up production files

Set up production files

![]() Assemble supply of production forms

Assemble supply of production forms

![]() Prepare a crew list

Prepare a crew list

![]() Prepare a contact list

Prepare a contact list

![]() Start a purchase order log

Start a purchase order log

![]() Prepare and distribute asset inventory logs

Prepare and distribute asset inventory logs

![]() Start a raw stock inventory and order log

Start a raw stock inventory and order log

![]() If a television series, prepare a list of episodes, production dates, director, writer, and editor for each show

If a television series, prepare a list of episodes, production dates, director, writer, and editor for each show

![]() Prepare DGA deal memos

Prepare DGA deal memos

![]() Prepare crew deal memos

Prepare crew deal memos

![]() Post and distribute safety, sexual harassment, code of conduct and Standards of Business Practices guidelines as required

Post and distribute safety, sexual harassment, code of conduct and Standards of Business Practices guidelines as required

![]() Distribute and post environmental guidelines

Distribute and post environmental guidelines

![]() Prepare a distribution list

Prepare a distribution list

Visual Effects

![]() Hire a visual effects supervisor

Hire a visual effects supervisor

![]() Prepare a breakdown of visual effects shots

Prepare a breakdown of visual effects shots

![]() Have conceptual designs and storyboards prepared, clearly defining each effect

Have conceptual designs and storyboards prepared, clearly defining each effect

![]() Determine methodology and exact elements required to accomplish desired effects

Determine methodology and exact elements required to accomplish desired effects

![]() Send breakdown, designs and storyboarded scenarios out to visual effects houses for bids

Send breakdown, designs and storyboarded scenarios out to visual effects houses for bids

![]() Determine time and expense necessary to accomplish each effect

Determine time and expense necessary to accomplish each effect

![]() Adjust script to accommodate budgetary and scheduling limitations if necessary

Adjust script to accommodate budgetary and scheduling limitations if necessary

![]() Select visual effects houses to create needed effects (i.e.,creatures, animation, computer-generated characters)

Select visual effects houses to create needed effects (i.e.,creatures, animation, computer-generated characters)

![]() Have effects supervisor prepare a schedule integrating pre–production, production and post production activities and all work to be done at effects houses

Have effects supervisor prepare a schedule integrating pre–production, production and post production activities and all work to be done at effects houses

![]() Determine which portion of each visual effects shot will need to be shot during production (i.e., process plates) and coordinate with the UPM and first assistant director, so requirements can be integrated into the shooting schedule

Determine which portion of each visual effects shot will need to be shot during production (i.e., process plates) and coordinate with the UPM and first assistant director, so requirements can be integrated into the shooting schedule

![]() Determine what special equipment you’ll need to order to be used during production (i.e., motion control camera, blue screen)

Determine what special equipment you’ll need to order to be used during production (i.e., motion control camera, blue screen)

![]() Line up additional, specially trained crew to work on the portions of effects that are scheduled to shoot during production

Line up additional, specially trained crew to work on the portions of effects that are scheduled to shoot during production

![]() Have effects supervisor prepare a contact list, including which effects houses are doing which effects, phone numbers, and names of who is supervising the work at each of the houses

Have effects supervisor prepare a contact list, including which effects houses are doing which effects, phone numbers, and names of who is supervising the work at each of the houses

Note: Complicated stunts and special effects to be shot during production should be assessed and planned during the early stages of pre–production as well. Preparation involves many of the same steps as those listed above.

Cast–Related

![]() Secure SAG bond (if applicable)

Secure SAG bond (if applicable)

![]() Finalize casting

Finalize casting

![]() Prepare a cast list

Prepare a cast list

![]() Send cast list to SAG

Send cast list to SAG

![]() Station 12 cast members

Station 12 cast members

![]() Prepare cast deal memos

Prepare cast deal memos

![]() Prepare SAG contracts

Prepare SAG contracts

![]() Schedule designated cast for medical exams

Schedule designated cast for medical exams

![]() Fit wardrobe

Fit wardrobe

![]() Hire a stunt coordinator

Hire a stunt coordinator

![]() Have stunt coordinator line up stunt doubles

Have stunt coordinator line up stunt doubles

![]() Hire a dialogue coach, if needed

Hire a dialogue coach, if needed

![]() Make sure actors’ dressing rooms and mobile homes are properly outfitted

Make sure actors’ dressing rooms and mobile homes are properly outfitted

![]() Check actors’ deals for perks, and make sure they have everything they’re contractually due

Check actors’ deals for perks, and make sure they have everything they’re contractually due

![]() Procure a supply of headshots from actors’ agents for hair, makeup, wardrobe, stunts, extra casting, assistant directors and office copy

Procure a supply of headshots from actors’ agents for hair, makeup, wardrobe, stunts, extra casting, assistant directors and office copy

![]() Hang a set of the main casts’ headshots on the wall in the production office, labeled with their names and their characters’ names (so the office staff knows who’s playing which part)

Hang a set of the main casts’ headshots on the wall in the production office, labeled with their names and their characters’ names (so the office staff knows who’s playing which part)

![]() Schedule wig fittings and hair coloring

Schedule wig fittings and hair coloring

![]() Schedule prosthetic fittings and molds, if necessary

Schedule prosthetic fittings and molds, if necessary

![]() Schedule actors for lessons (if special skills are required for their roles)

Schedule actors for lessons (if special skills are required for their roles)

![]() Schedule workouts, tanning sessions, etc. (if required)

Schedule workouts, tanning sessions, etc. (if required)

![]() Schedule rehearsal(s) and read-throughs

Schedule rehearsal(s) and read-throughs

![]() Schedule hair and makeup tests

Schedule hair and makeup tests

![]() Make sure minor performers have work permits

Make sure minor performers have work permits

![]() Hire studio teacher/welfare worker(s), as needed

Hire studio teacher/welfare worker(s), as needed

![]() Line-up an extras casting agency

Line-up an extras casting agency

![]() Interview stand-ins and photo doubles

Interview stand-ins and photo doubles

![]() Obtain a good supply of extra vouchers (union and nonunion)

Obtain a good supply of extra vouchers (union and nonunion)

Script and Schedules

![]() Finalize script

Finalize script

![]() Type script changes

Type script changes

![]() Duplicate script

Duplicate script

![]() Distribute script and all revisions to cast, crew, staff, studio/parent production company, insurance agency, casting agencies, research company/department and product placement agencies/department