Chapter 8

During the Shoot

THE PREP CONTINUES

Prep doesn’t stop when the filming begins. As long as there’s shooting to be done and changes that occur, there are preparations to be made (and remade). Although the production office is the center of all pre-production activities, during the shoot, all focus is on the set, and everything revolves around meeting the needs of the shooting company. Once principal photography begins, the goal of the line producer, the UPM, the assistant directors, the production coordinator and the rest of the production staff is to keep one step ahead of everyone else by making sure that sets are ready on time, special elements (i.e., equipment, prosthetics, picture cars, animals and the like) are there when needed, filming progresses as smoothly as possible, unexpected problems are resolved quickly, the director and DP are getting the footage they envisioned, the studio is happy and kept well informed, the set remains harmonious and the show is running on schedule and on budget. Be aware, however, that as hard as we try, there are times when everything doesn’t fall into place as it should. In fact, sometimes unexpected circumstances are more the norm than not. But that never stops us from striving to stay on budget, on schedule and achieve the best results possible.

THE SET

Deciding what to shoot each day starts with what’s reflected in the shooting schedule. Adjustments are made to accommodate changing weather conditions, working with minors and animals, the availability of certain locations or pieces of special equipment or the possibility that the show is running behind or ahead of schedule. Once the first assistant director, director and line producer agree with what’s to constitute a day’s work, it’s reflected onto a call sheet and distributed the evening before.

Other factors that affect call times would include sunrise and sunset hours when shooting exteriors. Daytime shoots can’t begin until the sky is light enough, and it can’t continue once it gets too dark out (and the reverse would be true when shooting night-for-night). Those restrictions don’t exist when shooting interiors, but once inside, it’s not unusual for call times to be continually adjusted throughout the course of a week. This happens when a shoot day runs longer than anticipated, and the call time for the next day is pushed (made later) to accommodate requisite turnaround times. As the week progresses, call times are often pushed later and later, so what started out as a 7 a. m. call time on Monday may very well be a 10 or 11 a. m. call by Friday. And although Friday may be a very late night indeed, because of the weekend ahead, the call time can be an early one again on Monday morning.

Exterior shoot days are sometimes scheduled to accommodate both day and night scenes, and those would require mid-day call times. And based on the script, often these split days gradually morph into full night shoots.

Actors and stunt performers are given work calls to accommodate the time it takes them to get through wardrobe, hair and makeup and crew members are likewise given call times to accommodate the amount of prep time they need. More time is always needed when shooting in a new location. Less setup time is required when returning to a long-standing set on a sound stage or other interior location. When shooting on a distant location, drive-time to and from the set is also factored into the work day.

Each day is different. Sometimes a succession of scenes is completed, sometimes just portions of one scene. Much will depend on what type of show it is, the schedule and budget and also how complicated any particular scene is. A one-page scene of two people sitting at a table talking is going to take a lot less time to shoot than a one-page scene full of car crashes, stunts and explosions. One complicated scene (such as one on a battlefield) could take several days to accomplish (as well as multiple cameras and second units). Much will also depend on the amount of coverage any one scene is given. Low-budget films and TV shows with inflexible schedules and budgets don’t have as much latitude when it comes to creative lighting and camera moves.

Let’s just say you have a scene where several people are sitting around a table talking and having dinner. Coverage would normally begin with a master shot, often achieved with a wide angle lens to encompass everyone who’s in the scene. Subsequent coverage might include two-shots, close-ups, over-the-shoulder shots and high-or low-angle shots. If the table were outside on a rooftop, the director might want an aerial shot (captured via helicopter). The more coverage the director is able to get, the more footage the editor has to work with. Every time the camera is moved, however, another set-up is created, and lights, equipment and sometimes flats (walls) must be moved to accommodate the shot. If the entire scene is played out in the master, then each subsequent setup represents a portion of that scene, sometimes requiring many takes until the director is ready to move on. Multiple setups and takes equate to a lot of waiting around, and those new to working on a set are always surprised at how slowly things move (especially on features).

The same basic sequence of events occur over and over again throughout the day. They are:

1. Rehearse: the director works with the actors as they go over their lines and get a sense of the scene.

2. Block: decisions are made as to where the actors will be standing, how the scene will be lit and where the camera(s) will be placed. Once finalized, the principal actors are dismissed (to deal with wardrobe, hair, make-up, prosthetic fittings, etc. or to just relax and go over their lines in their dressing rooms). At this point, the stand-ins are brought in for the purpose of lighting.

3. Light: the DP and gaffer are now in charge of lighting the set as per the director’s wishes.

4. Shoot: once the set is lit, the stand-ins are dismissed and the principal actors are brought back in to shoot. (It’s the second assistant director’s responsibility to make sure the actors are ready once the set is ready for them.)

COMMUNICATIONS

During every shoot, in addition to those working on the set and in the office, there are usually construction, set dressing and rigging crews prepping subsequent and/or wrapping previous sets. The company is spread out, and everyone not on the set wants to know what’s happening on the set. The burning question of the day is “How are they doing?” Are they on schedule, and will they finish the day on time? Was the stunt successful? Was the explosion big enough? Was the weather clear enough to make the helicopter shot? Decisions are made, schedules juggled, locations changed, scenes added or deleted - all based on the status of the filming activities occurring at any given time. Needless to say, good and constant communications between the set, the office and those prepping the next scheduled location site and/or set is vital, especially when there’s a problem, delay or injury. Whether it’s using a dedicated land line or cell phone or sending a text message, there should always be a way for the office to reach the set, and for the set to reach the office. The UPM, key second assistant director and the second second AD should all have cell phones.

Second assistant directors are required to regularly report in at certain times: the first shot of the day, when the company breaks for lunch (the “lunch report”), the first shot after lunch and wrap, including which scenes have been completed along the way. If there’s an accident or injury, they should call in as soon as the situation has been contained, so the office staff can call the insurance company, help with medical arrangements, dispatch additional crew members or whatever else it takes to make sure everyone is taken care of and that filming resumes as quickly as possible. Someone from the production office (assistant coordinator or production secretary) then takes the constant set updates and e-mails the information to all appropriate parties, such as the producers, UPM, studio, network and/or bond company.

In addition to receiving status reports from the set, it’s also important for the line producer and/or production manager to keep a good line of communication open with department heads — checking in with each of them on a regular basis, and when not on the set, being accessible to them when they call or come to the office to ask questions, order additional equipment or discuss impending needs and/or concerns. Being tuned-in to your crew and having them know that you’re there to support them to the best of your ability (and budget) goes a long way to promote a well-functioning set.

There should also be a good communication channel between the production office and the transportation department — the transportation coordinator, captain and dispatcher (if there is one). There’s a constant flow of movement throughout the day — pickups, deliveries, actors to be transported, runs to the set, trips to the airport, etc., and most of the details needed to make these runs originate from the production office. When dealing with Transpo, be clear as to time frames, and don’t declare an emergency unless there truly is one. Let them know as soon as you know what your needs are going to be, so they can best schedule their drivers. You might also consider using the Request for Pickup/Delivery Slips found in Chapter 2.

THE DAILY ROUTINE

Also during the shooting period:

• An assortment of paperwork is sent in from the set each night; some of it is e-mailed, and what can’t be, is usually waiting for the office staff when they arrive each morning. Some of it may be on a flash drive (the production report is often sent on a flash drive, especially if it can’t be e-mailed from the set). The rest of the documents will be hard copies. They’re copied, filed, acted upon and/or distributed as needed (see Paperwork from the Set, coming up in this chapter). We used to refer to the envelope that carried all of this paperwork as the nightly “pouch,” but the more common term is “football,” as it’s continually sent back and forth between the set and office. Often an accordion file serves as the football, because it has a number of pockets — perfect for the various documents that are shuttled back and forth each day. These folders can be fastened shut, so nothing falls out.

• Among the morning paperwork is an abbreviated version of the production report (called a Daily Wrap Report or Daily Hot Sheet), which highlights the previous day’s shooting activities. This information is immediately sent to the studio or bond company, the producer(s), production manager, accountant and coordinator. If one isn’t sent in from the set, the information is pulled from the uncorrected production report and script supervisor’s report, and the report is completed and issued by the assistant production coordinator.

• When the full production report is sent in from the set, it’s reviewed by the production coordinator and UPM. Corrections are made as needed, and the report is printed, signed and distributed. On some shows, final production reports are generated by the assistant production coordinator, and on others, by the 2nd AD or 2nd 2nd AD from the set. When it’s done from the office, the corrections need to be sent to the 2nd AD as soon as possible, so accurate totals and information can be properly carried forward.

• When shooting exteriors or planning to shoot exteriors, it’s important to monitor weather conditions. On days when the weather is precarious at best, UPMs, ADs and/or coordinators will check the weather several times a day (possibly every hour or two, and sometimes into the night) so cover sets can be planned. If the weather has been acceptable and holding steady, checking it just once in the evening and again first thing in the morning may be sufficient. If your production has signed up with a weather service, the report should be e-mailed and/or faxed to you at least once a day. Otherwise, the information is available on the Internet (one such website is www.weather.com).

• Also upon arriving each morning (if you’re shooting on film), a call is made to a designated contact at the lab to make sure there are no problems with the film sent in for processing the night before. Negative scratches or tears, out-of-focus shots, etc. could (if acceptable alternative takes aren’t available) necessitate reshooting and/or insurance claims. An “all-clear” lab report can also be the signal to set dressing and construction to start striking sets no longer needed.

• Runs are coordinated between the set and the office throughout the day, and cars and drivers are arranged for actors whose deals include being picked up and driven home from the set.

• New equipment is continually being ordered, and equipment no longer needed is returned. There is constant communication with vendors, new purchase orders to generate and pickups and deliveries to be scheduled.

• Although the 2nd AD on the set is responsible for continually checking in with the office, it’s the office staff’s responsibility to regularly report in to the studio or parent company with set updates. (Some studios require status reports to be made at specifically appointed times, such as 11 a.m. and 4 p.m.)

• If on a distant or foreign location, on a road show that’s constantly on the move or if more than one unit is operating at one time from different locations, there is a continuum of travel and hotel arrangements to be made, new crew members starting and others wrapping, new locations to set up and others to strike, a voluminous amount of shipping to coordinate and movements to keep.

• Quantities of office supplies, materials, expendables, film stock, etc. are constantly being monitored and reordered as needed.

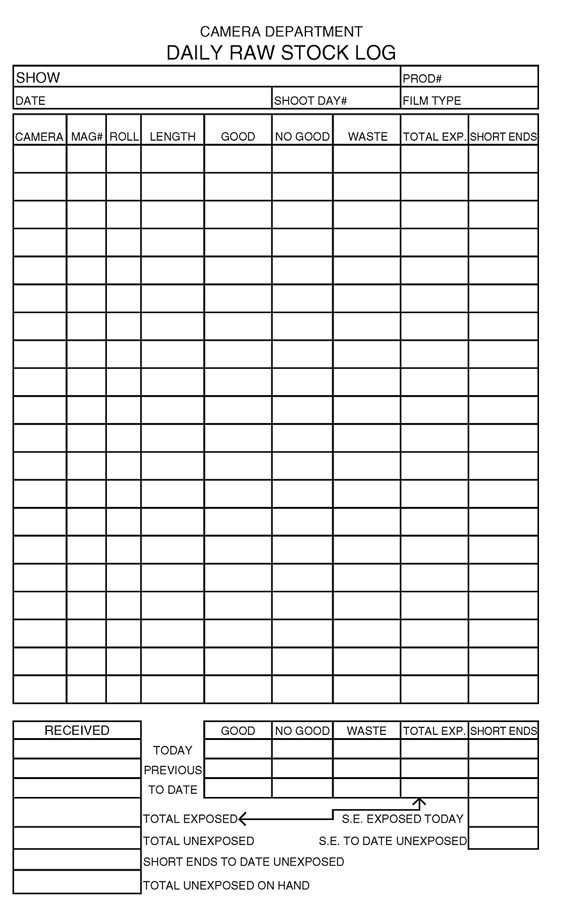

• Raw (film) stock should be constantly monitored. This is done by keeping track of what’s ordered, how much has been used (as per the production reports) and how much should be remaining at all times (see Raw Stock Inventory form at the end of the chapter). Approximately once a week, this amount should be compared to what the assistant camera person physically has on hand. This way, the film is being accounted for, and chances are, you won’t be caught short. Care must be placed when ordering as well, so the DP has the stocks and quantities needed without there being too much left over at the end of the shoot (also see Raw Stock Order Log at the end of the chapter).

• Script and/or schedule changes are continually being generated and distributed.

• Dailies are coordinated. More often than not these days, the producer, director and DP receive DVDs of dailies, and on some shows, they’re also screened, streamed or uploaded. They may also be screened for the studio, network or parent company. (Read more about the coordination of dailies in Chapter 30.)

• New cast members are starting all the time, necessitating new contracts and deal memos, wardrobe fittings, additions to the cast list, travel plans (if necessary), etc.

• “Sides” are prepared and sent to the set toward the end of each day to be used the following day. Sides are script pages that contain the scenes to be shot that day. They eliminate the need to carry around a complete script and serve as handy references for cast members and certain department heads. They’re copied from an original all-white script (even the change pages are in white) at a reduced size (usually 64 percent, making them easy to tuck in a pocket or bag), and a reduced-sized call sheet is often used as a cover page. Some assistant directors will ask for the sides to include just the scenes to be shot and others will ask the office to add the scenes preceding and following each scheduled scene. Some ADs prefer that the sides be assembled by scene number — not necessarily according to how they’re scheduled be shot. When script revisions are issued affecting sides that have already been sent to the set, new sides are issued on blue paper and sent out as soon as possible. The 2nd AD will let the office know how many sets of sides to prepare.

• Some directors and assistant directors also like to have a supply of mini scripts on the set at all times. To accomplish this, the script is copied horizontally in booklet form, and once assembled, are approximately 4¼“×9”.

• Call sheets are sent (e-mailed) in from the set toward the end of each shooting day, and if photocopied on or near the set, the office staff photocopies the call sheets and attaches all maps, safety bulletins and memos pertinent to the next day’s shooting, sending a given amount back to the set for distribution at wrap. If the call sheets are photocopied on-set, then an electronic copy is still e-mailed to the office to be forwarded to everyone not on the set. Copies are made and distributed to the office staff; and copies are e-mailed or faxed or calls are made to a predetermined list of individuals (production executives, background casting, catering, studio teacher, additional crew members needed for the next day, etc.) informing them of call times, directions and any special requirements. (Note that call times for actors are not generally made from the production office, as that’s the responsibility of the 2nd AD.) If the call time changes (which may happen — sometimes more than once), revised call sheets are distributed and new calls made to everyone on the list.

• The UPM always has a stack of POs, check requests, invoices and time cards to review and approve. Some UPMs like having the coordinator and/or accountant sit with them while working through the stack, so that specifics can be discussed, clarified and evaluated before approvals are granted.

• Once a week, approved, original Exhibit Gs are sent to SAG, and a DGA Weekly Work List is sent to the Director’s Guild.

• Along the same lines, the studio production executive, producer, UPM and production accountant will meet (together or any two or three at a time) at least once a week (usually after the cost report is issued) to discuss how the show (and each department) is doing financially (under, on or over-budget). It’s important for all the key players to be able to discuss areas that are going over-budget and to (hopefully) agree upon realistic solutions. On a more immediate basis, it’s not uncommon to come up against expenditures that could not have been predicted and are not apparent until shooting begins. Unexpected circumstances will often create a desire or need for additional (unbudgeted) scenes, days, sets, equipment, additional units, etc. Although the studio/parent company has the final word, these issues are usually discussed by the producer and production manager in an effort to reach a decision or compromise that will be in the best interest of the film. Staying on top of costs, being aware of where the budget is at all times and working out solutions to unexpected expenditures are part of the everyday challenge of efficiently managing a film shoot.

CALL SHEETS AND PRODUCTION REPORTS

Briefly discussed earlier, a call sheet is a game plan for what’s to be shot the following day — who’s to work, what time and where they’re to report, and what, if any, are the special requirements needed to complete the day.

Call sheets are created by the 2nd assistant director. A preliminary version is usually prepared early in the day; an approved version, signed by the UPM, sometimes goes out by late afternoon. But in the event of changes (or anticipated changes), the call sheet isn’t distributed until shortly before wrap — or wrap. Wrapping 15 minutes or a half-hour late may push the next day’s call by 15 minutes or a half-hour. If the call sheets are photocopied before a call is pushed, they’re generally stamped with the notation: ALL CALLS PUSHED 1/4 HR., ALL CALLS PUSHED 1/2 HR., etc. Call sheet changes affecting scenes to be shot, locations, various work times, etc. are issued on blue paper. A subsequent change would come out on pink.

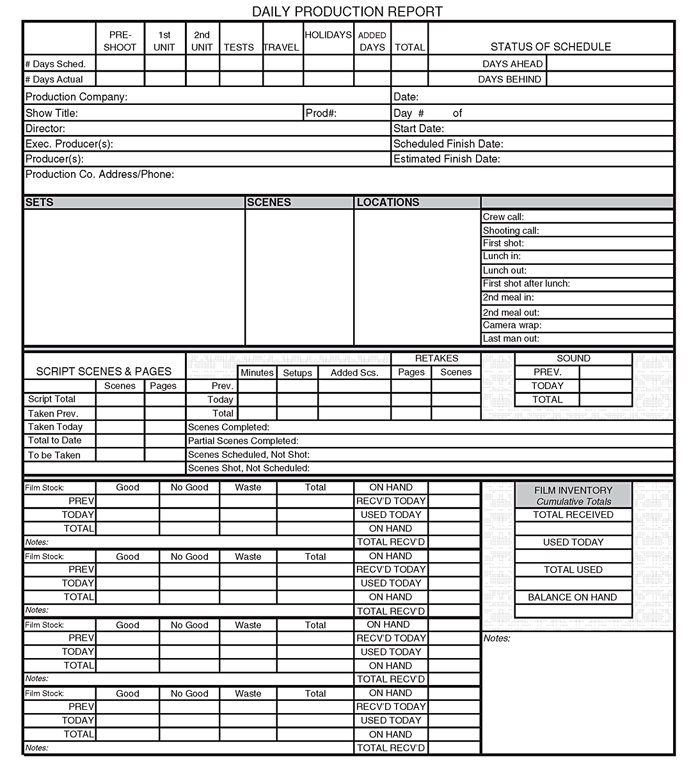

The Daily Production Report (or “PR”) is the official record of what was shot that day in terms of scene numbers, setups, minutes, film footage and sound rolls; who worked and the hours they worked; the locations shot at (actual and scripted); how many meals were served; vehicles and equipment that were used and the delays, accidents or notable incidents that may have occurred.

Production reports are used to help evaluate the overall progress of principal photography; help assess production costs; check invoices against equipment and vehicles used; inventory raw stock; back up workers’ compensation and other insurance claims; track safety meetings and check cast, crew and extras’ workdays and times against submitted time cards. It’s therefore imperative that they be as accurate as possible.

Also prepared by the 2nd AD or 2nd 2nd AD, these reports include information taken from the script supervisor’s daily report (indicating the exact scenes added, deleted and shot; the number of scenes, pages, setups and minutes shot and the call time, first shot, meal times [in and out], first shot after lunch and wrap time); the camera loader’s camera report (indicating film footage printed, footage shot but not printed, wasted footage, short ends [leftover footage at the end of a roll] and total footage used) and the sound mixer’s sound report (indicating the number of DAT tapes or DVDS used). Each of these items are listed in terms of what was Previously shot, used or taken; what was shot, used or taken Today and the Total shot, used or taken to date.

When the PR is sent in from the set, it’s stamped UNAPPROVED. The UPM, production coordinator and/or assistant coordinator will then go through it, making sure:

• All dates, locations, shoot days and times are properly recorded

• All figures from the previous day’s PR are correctly carried over

• Start, Work, Hold and Finish days are correctly indicated and that actors’ times on the Exhibit G match those on the PR

• Camera report totals are correct and accurately carried over from the previous day

• Sound roll figures are correct

• Partial and completed scenes are credited properly

• Notations are made to indicate alternate coverage of nude scenes and the replacement of bad language for TV distribution

• The caterer’s daily receipt matches the recorded number of meals served

• All special equipment used for that day is indicated

• All injuries, accidents and major delays are recorded

• Call times for the entire crew are noted

• Any additional crew members working that day are indicated

• The “skins” (list of extras to work that day issued by the background agency) match the background talent listed on the PR

• Safety meetings are noted

The accountant and payroll accountant will also go through unapproved production reports to make sure that all the information they need has been properly noted.

A separate production report should be prepared for second unit, although one production report is often issued when the second unit is very small and shoots simultaneously at the same location or if a splinter unit made up of first-unit crew shoots concurrently at the same location.

The UPM and/or production coordinator, after checking the PR, will discuss any discrepancies with the 2nd AD. After corrections and additions are made, the UPM (and sometimes the 1st AD) will sign off on it. If subsequent changes are made after the report has been signed, copied and distributed, updated versions are issued and labeled “Revised.”

People are handed call sheets and production reports each day, but they’re easily misplaced — left at home, buried in a pile on the desk, left in a jacket pocket, in the car or in a trailer room. The production office staff is therefore often asked to assemble complete sets of each for several different people at the end of the show. It’s easier to distribute complete sets of call sheets and production reports on CD, but sometimes you’ll still find individuals who will want hard copies. For those who do, I suggest you prepare two legal-sized file folders (one for call sheets and one for PRS) for the producer(s), director, UPM, 1st AD, Key 2nd AD, production supervisor and/or coordinator and studio production executive, and to add a final call sheet and production report to the respective folders on a daily basis; so by the end of principal photography, full sets are already compiled and ready to distribute.

PAPERWORK FROM THE SET

An assortment of paperwork is sent in from the set to the production office at the end of each day’s filming. One person in the office should be the designated set paperwork person (it’s usually the production coordinator or assistant coordinator), and going through the daily stack (the copying, distributing and handling of) should be a first-thing-in-the-morning priority, as much of it is time-sensitive. These are the types of things that will arrive in the morning “pouch” or “football.”

• Unapproved production report — to the production coordinator or assistant coordinator to check, but also give copies to Accounting, to the UPM and to Editorial

• Completed start slips, W-4s, I-9s, time cards, box rental inventories and invoices and vendor receipts — to Accounting

• Extra vouchers — to Accounting

• Completed check requests and petty cash envelopes — to Accounting

• Camera reports — a copy to Editorial and a copy to the coordinator to check before being placed in the Day File

• Sound reports — same as above

• Script Supervisor’s Daily Report and notes (attached to the lined script pages) — to Editorial and to the coordinator to check before placing in the Day File

• On some productions, the telecine house requires certain paperwork (the script supervisor’s reports, camera reports, sound reports, film inventory, etc.) by a certain time each day to make their deadline.

• Exhibit Gs — the morning copy should be stamped “unapproved” and sent out for distribution to: Accounting, the UPM, Casting (ask if they want it) and to the coordinator or assistant coordinator to check the times against the PR. The UPM signs off on the Gs once they’ve been checked and all changes have been made, and then they’re redistributed, with a copy going into the Day File and one in an envelope labeled “SAG.” Exhibit Gs are sent to SAG once a week, and to get a jump on this, you might want to prepare in advance a number of envelopes addressed to SAG — one for each week you’ll be shooting. That way at the end of each week, you’ll just have to weigh the envelope and add the postage.

• The caterer’s receipt — to Accounting and the coordinator to check before filing

• Skins — to Accounting and to the coordinator

• Signed SAG contracts — to the coordinator, who will then obtain the producer’s signature and distribute copies accordingly

• Workers’ compensation and auto accident reports — to the coordinator to complete, add to the claim log and submit to the respective insurance companies

• Crew requests for equipment and/or expendables — to the coordinator to obtain UPM approval, prepare POS, place orders and arrange for pickup

• Completed Daily Safety Meeting reports — to be kept on file

THE SCRIPT SUPERVISOR’S ROLE

This book doesn’t detail job descriptions, but I thought it worthwhile to briefly mention the responsibilities of the script supervisor. A good script supervisor is not only an essential element of a well-functioning set, but is necessary to the editing process as well. This is a position that isn’t always understood nor fully appreciated.

A script supervisor is part of the director’s on-set team. On features and commercials, they’re selected by the directors, and on TV shows, they’re hired by the producers or UPMS. They use their prep time to breakdown the script and are usually asked to pre-time the script as well. Timing a script requires the visualization and acting out of scenes with a stop watch in hand to come up with a reasonable estimate of the final, edited, first-cut running time of the film. Written breakdowns are submitted indicating the predicted running time of each scene. Timings are valuable in determining whether a script is too long or too short.

Positioned with the director behind the camera on set, the script supervisor keeps track of:

• Scenes, pages, setups and minutes shot

• Which scenes are shot (including partially shot), which are deleted and which ones are left to be shot

• Setups filmed by all cameras

• Deviations from scripted dialogue

• Set times: crew call, first shot, meal times (in and out), first shot after lunch, last shot and wrap

• “Matching” for purposes of continuity — making sure the appearance of the set and the actors, the movements (and eyelines) of the actors and the delivery of dialogue within each take matches its original master scene and that the progression of wardrobe, makeup, props and set dressing during any specific scene is accurate

• Whether the picture is running long or short

The script supervisor keeps a set of notes each day (usually in the form of a daily log), recording each take of each scene shot, including a description detailing the action and camera movements. Also recorded is the camera roll, scene number, take number, the timing of each take, the camera lens used and the page count credited to each take. The director will call for specific takes to be printed, and those are circled, thus the term “circled takes.”

The script supervisor also:

• Furnishes Camera and Sound with slate numbers

• Prepares a list of pickup shots and wild sound tracks

• Assists during the blocking of scenes

• Runs lines with and cues actors prior to and during rehearsals (not a required duty but very often done)

• Reads off-stage lines for actors not present on the set

• Supplies the editor with a complete log, continuity notes and lined script pages (actual lines made through the specific scenes being shot indicating the exact action and dialogue captured in each take)

Years ago, thinking at the time I might want to be a script supervisor, I was allowed to shadow a script supervisor friend of mine who was working on a TV series at the time. He not only let me observe what he was doing, but at some point, he let me practice — allowing me to sit off to the side timing takes, keeping my own lined script and taking all of the appropriate notes. And then, between takes, when he had finished with his own notes, he’d quiz me: “On what word did the actor place his glass on the table?” And of an actor who had gotten drenched the day before in an exterior shot and had just walked into a room that was to be a continuation of that scene, he asked, “How wet is he supposed to be?” Some of my answers were right and others weren’t, and at the time, all I kept wondering was: “How can one person possibly remember what seemed like thousands of minute details that had to be continually tracked and matched?”

Having the presence of mind and concentration required to stay totally aware of everything going on around them; listen to the director’s instructions; be aware of camera movements; keep thorough notes and timings; account for scenes, pages, setups and minutes shot; help actors with their lines; match dialogue and movements and create a lined script for the editor (doing several of these things simultaneously) is a challenging set of responsibilities at best. Not having a good script supervisor will have far-reaching consequences. The good ones are worth their weight in gold.

At the back of this chapter are samples of a Script Supervisor’s Daily Report and Script Supervisor’s Daily Log, which are the type of forms still used by some. But technology has caught up with script supervising, as it has almost all other aspects of filmmaking, and there is no standard way to do it anymore. Script Supervisor Kris Smith explains:

There are several methods in use today for digital script supervising. Personally, I use FilmMaker Pro for my forms. It’s a database program that allows you to enter the information only once, and then that same information is available whenever you need it. It’s a great time-saver. Other people use Excel, and some Word.

I also use a software program called Continuity to line my script in the computer. And I use a capture device that I’ve cabled into the back of the monitors that allows me to grab still photos during a take. It’s great for double checking continuity, shot sizes and eyeline angles — even wardrobe, hair, props and set dressing if needed.

Again, there are several other ways to do this. Some people use the drawing tools available in Adobe Acrobat or Bluebeam software. These programs weren’t really made for the purpose of script supervising, and while they have their drawbacks, other script supervisors seem to get by with them. Then there’s ScriptE www.scriptesystems.com). Recently introduced to the market, it’s a new all-encompassing software system that was designed exclusively for script supervisors.

So if you’re a script supervisor, you’ll have a lot of homework to do before deciding which system is most comfortable and affordable for you.

THE DAY BEFORE

Here’s a little checklist I’ve used to make sure that everything needed for the next day’s shoot is lined up. Not everything listed is going to be applicable each day, but it’s a helpful way to remember what needs to be done.

![]() Order raw stock if needed (confirm order with DP, have order approved, do a PO and arrange for pickup)

Order raw stock if needed (confirm order with DP, have order approved, do a PO and arrange for pickup)

![]() Station 12 actors

Station 12 actors

![]() Prepare SAG contracts (e-mail copies to agents as necessary)

Prepare SAG contracts (e-mail copies to agents as necessary)

![]() Send additional start paperwork packets and scripts to the set

Send additional start paperwork packets and scripts to the set

![]() Distribute script and schedule changes

Distribute script and schedule changes

![]() Workers comp forms to the set for the set medic

Workers comp forms to the set for the set medic

![]() Send copies of location permits to the set

Send copies of location permits to the set

![]() Confirm or order special or additional equipment (do the PO and arrange for pickup or delivery)

Confirm or order special or additional equipment (do the PO and arrange for pickup or delivery)

![]() Line up studio teacher/welfare worker and make sure there’s a room or trailer to use as a schoolroom

Line up studio teacher/welfare worker and make sure there’s a room or trailer to use as a schoolroom

![]() Order dressing rooms or additional cast trailers (do PO and arrange for delivery)

Order dressing rooms or additional cast trailers (do PO and arrange for delivery)

![]() Order additional walkie-talkies (and send walkietalkie sign-out sheet to the ADs on the set)

Order additional walkie-talkies (and send walkietalkie sign-out sheet to the ADs on the set)

![]() Call in drive-ons

Call in drive-ons

![]() Skins

Skins

![]() Sides

Sides

![]() Mini scripts

Mini scripts

![]() Line up stand-by ambulance (do PO and give ambulance company a call time)

Line up stand-by ambulance (do PO and give ambulance company a call time)

![]() Send a PO out to the set for the camera department (made out to the lab)

Send a PO out to the set for the camera department (made out to the lab)

![]() Send a PO out to the set for the sound department (made out to the sound facility)

Send a PO out to the set for the sound department (made out to the sound facility)

![]() Order any needed expendables (do PO and arrange for pickup)

Order any needed expendables (do PO and arrange for pickup)

![]() Camera?

Camera?

![]() Grip?

Grip?

![]() Electric?

Electric?

![]() Golf carts?

Golf carts?

![]() Coordinate dailies

Coordinate dailies

![]() Call sheet distribution

Call sheet distribution

RESHOOTS

Reshoots are sometimes scheduled for shortly after the completion of principal photography or may be months later. They can last a day or two or a matter of weeks. They can entail a local shoot that’s fairly routine and easy or require traveling, packing, shipping and working on distant locations. There’s often not much money left in the budget by the time reshoots roll around, so prep and wrap times are often brief and fast-paced. To retain the same look and tone of the film, to walk in knowing how the director works, how to keep the actors happy and how to pull off the same logistical requirements, it’s always preferable to hire as many people from the original shoot as possible. But for those unavailable, you want replacements who are qualified and adept at picking up where someone else left off. And when doing reshoots for a major studio, it’s best to hire people who have worked on films for that studio before. It’ll shorten their learning curve tremendously. And just in general, whether it’s your DP or PA, this isn’t the time to hire anyone who doesn’t move quickly and have the right level of experience, because you won’t have the time for on-the-job training.

Here’s a quick little checklist to help you prepare for reshoots and additional photography. It doesn’t include travel and shipping - just the basics, and it’s based on the assumption that your cast and director are available.

![]() Contact your insurance rep, and let him or her know you’re going to be shooting. Make sure your policies are current and you can start issuing certificates of insurance.

Contact your insurance rep, and let him or her know you’re going to be shooting. Make sure your policies are current and you can start issuing certificates of insurance.

![]() Bring on an accountant, production coordinator and a PA to start with.

Bring on an accountant, production coordinator and a PA to start with.

![]() Set up new (very temporary) offices, phones, etc., and make sure all departments have enough space to work.

Set up new (very temporary) offices, phones, etc., and make sure all departments have enough space to work.

![]() Secure a sufficient supply of start paperwork packets, checks, purchase orders, check requests, petty cash and petty cash envelopes.

Secure a sufficient supply of start paperwork packets, checks, purchase orders, check requests, petty cash and petty cash envelopes.

![]() Prepare a new shooting schedule and budget.

Prepare a new shooting schedule and budget.

![]() Locate wrap and continuity books, artwork, wardrobe, props, wigs, set pieces, etc. — anything you need from the original shoot.

Locate wrap and continuity books, artwork, wardrobe, props, wigs, set pieces, etc. — anything you need from the original shoot.

![]() Line up your crew. Prepare deal memos for those who are new.

Line up your crew. Prepare deal memos for those who are new.

![]() If your cast includes minors, make sure their work permits (for the state where you’re going to be filming) are current, line up a teacher and procure space for a school room.

If your cast includes minors, make sure their work permits (for the state where you’re going to be filming) are current, line up a teacher and procure space for a school room.

![]() Secure locations and all necessary permits and/or needed stage space.

Secure locations and all necessary permits and/or needed stage space.

![]() Check out the lead cast contracts, and make sure you have all contractual perks covered (including travel, pickups to the set, dressing room/trailer requirements, assistants, etc.)

Check out the lead cast contracts, and make sure you have all contractual perks covered (including travel, pickups to the set, dressing room/trailer requirements, assistants, etc.)

![]() Prepare new contracts for those actors whose contracts don’t cover reshoots.

Prepare new contracts for those actors whose contracts don’t cover reshoots.

![]() Order equipment, and arrange for pickups.

Order equipment, and arrange for pickups.

![]() Take care of all necessary rental agreements.

Take care of all necessary rental agreements.

![]() Station 12 your actors.

Station 12 your actors.

![]() Alert the lab that there will be more film coming in.

Alert the lab that there will be more film coming in.

![]() Prepare a dailies schedule with Post Production.

Prepare a dailies schedule with Post Production.

![]() Have bags, cans, cores and camera reports picked up from the lab.

Have bags, cans, cores and camera reports picked up from the lab.

![]() Order walkie-talkies (and cell phones if needed).

Order walkie-talkies (and cell phones if needed).

![]() Prepare new cast, crew and contact lists.

Prepare new cast, crew and contact lists.

![]() Prepare a box of paperwork to take to the set that includes: payroll start packages (regular and loanout), DGA deal memos, time cards, extras’ vouchers, a few office supplies, crew lists, script pages, call sheets, copies of permits and location agreements, workers compensation claim forms, SAG contracts and Exhibit Gs.

Prepare a box of paperwork to take to the set that includes: payroll start packages (regular and loanout), DGA deal memos, time cards, extras’ vouchers, a few office supplies, crew lists, script pages, call sheets, copies of permits and location agreements, workers compensation claim forms, SAG contracts and Exhibit Gs.

The best possible scenario you can hope for is that the show was wrapped properly, and the reshoot crew has access to everything they need — artwork, blueprints, wardrobe, wigs, the same makeup, prosthetics, props, set dressing, set pieces, etc. It’s when certain items can’t be located or are in another state that a tight schedule becomes even more challenging. Because, then, on top of everything else, there’s usually a fair amount of rushing around to ship items you hope will get to you in time and/or to have to recreate and match items that are no longer accessible.

Once reshoots are completed, your wrap time will be shorter than usual — possibly just a day or two. So here’s a short checklist of things you’ll want to make sure are taken care of before you take off:

![]() Have equipment and all other rentals returned.

Have equipment and all other rentals returned.

![]() Return unused/unopened film for credit or refund.

Return unused/unopened film for credit or refund.

![]() Coordinate runs to the lab.

Coordinate runs to the lab.

![]() Make sure all start paperwork and time cards are filled out properly and signed, and get them to Accounting.

Make sure all start paperwork and time cards are filled out properly and signed, and get them to Accounting.

![]() Submit all reports of loss and damage.

Submit all reports of loss and damage.

![]() Have all SAG contracts countersigned.

Have all SAG contracts countersigned.

![]() Send copies of all contracts and Exhibit Gs to Accounting.

Send copies of all contracts and Exhibit Gs to Accounting.

![]() Send copies of Exhibit Gs to SAG.

Send copies of Exhibit Gs to SAG.

![]() Make sure DGA deal memos are signed, send a copy to your production executive and send one to the DGA.

Make sure DGA deal memos are signed, send a copy to your production executive and send one to the DGA.

![]() Make sure the production report is turned in and distributed.

Make sure the production report is turned in and distributed.

![]() Submit all certificates of insurance to your risk manager or insurance broker.

Submit all certificates of insurance to your risk manager or insurance broker.

![]() Complete and submit a DGA Weekly Work List.

Complete and submit a DGA Weekly Work List.

![]() Make sure your production executive gets copies of all signed SAG contracts, Exhibit Gs, deal memos, location agreements, etc.

Make sure your production executive gets copies of all signed SAG contracts, Exhibit Gs, deal memos, location agreements, etc.

![]() Return previously-stored show assets such as props, set dressing and wardrobe (have wardrobe cleaned before returning).

Return previously-stored show assets such as props, set dressing and wardrobe (have wardrobe cleaned before returning).

![]() Inventory and submit any new assets purchased for the reshoots.

Inventory and submit any new assets purchased for the reshoots.

![]() Return borrowed office furniture and/or equipment.

Return borrowed office furniture and/or equipment.

![]() Sell short ends.

Sell short ends.

![]() Create a new wrap book or add a RESHOOTS section to the already existing wrap book.

Create a new wrap book or add a RESHOOTS section to the already existing wrap book.

DAILY WRAP

The following steps are taken when wrapping a set for the night:

• Walkie-talkies are collected, accounted for and placed in chargers

• The location site is cleaned

• Equipment is locked in trucks or securely stored

• Remaining vehicles are locked

• Dressing rooms are cleaned

• Copies of signed agreements, contracts and permits are in hand for the next day’s filming activities

• Special arrangements for the next day (equipment, stunts, effects, etc.) are set

• Supplies of paperwork, blank forms, and office supplies have been replenished

• Script notes, camera and sound reports, Exhibit Gs, time cards, etc. are collected to send to the office

• Exposed film is sent to the lab

• Pickups and returns for the next day are confirmed with Transportation

• Everyone has a call sheet and map for the next day

• The caterer knows how many meals to prepare for the next day

• Security is in place for the night

ON THE LIGHTER SIDE

We all work too many hours and too hard not to have some fun, and there’s nothing like interjecting a bit of humor into a long, hard day to alleviate stress. When the shows we work on are over, the lasting memories we walk away with are not only linked to the work itself, but also to the camaraderie and good times we’ve shared with our co-workers. The following are examples of how to create some of those lighter moments:

• I collect jokes and keep a selection of the best ones in a folder marked JOKES. For the past several years, that folder has been tacked up on the wall in each of my production offices. When someone feels they need a short break, or a laugh, they walk over to the folder and pull out a joke or two.

• In addition to the folder, I will sometimes post a JOKE OF THE WEEK or QUOTE OF THE DAY. The quotes are silly, like: “If At First You Don’t Succeed, Skydiving Isn’t For You,” “If They Don’t Have Chocolate In Heaven, I Ain’t Goin’!” and “Beware — The Toes You Step On Today May Be Attached to the Backside You Have to Kiss Tomorrow.” On one show I was working on, my friend Mark Indig, commenting on the quality of my jokes, took his pen to the “Joke of the Week” banner and made it read “Joke of the Weak.” That in itself, created some needed humor in the office.

• Some films start the production process with just a working title of the project, and the crew is occasionally recruited to help name the film. Whether ultimately used or not, sometimes small prizes are given for the most original title, the most humorous title and/or the most fitting title. Even on shows with firm titles, someone often posts a piece of paper near the coffee machine soliciting alternative (humorous) titles. One project I worked on (called The Thirteenth Year) was about a 13-year old boy who discovers that his mother is a mermaid, while his own body is starting to change and evolve into that of a merman. Jerram Swartz, our 1st AD, posted the initial list: When You Fish Upon a Star, A Buoy’s Life, Oh Cod, Sole Man, etc.

• Jerram also told me about a series he had worked on where they chose a crew Employee of the Week, the winner receiving an “Atta Boy!” award certificate and a prize of $50. It was a terrific morale booster and well worth the expense.

• On one show I worked on, which took place largely on water, we had our own awards ceremony at the wrap party. The awards were for categories such as: The Gal The Guys Most Want To Be Lost At Sea With, The Guy The Gals Most Want To Be Lost At Sea With, Best All-Round Sport, Best Sun Tan, etc. We bought little trophies and gag gifts to hand out, and everyone was falling off their seats with laughter. (Note: know your crew and avoid anything like this that might possibly offend anyone.)

• Mark Indig (the same one who doesn’t like my jokes) told me that while working on a picture in Miami Beach, they had a “Tackiest Souvenir” contest that was hilarious.

• A select group of crew members on one of the shows I worked on had T-shirts printed up with memorable comments that had been made by the director, producers and various crew members. They went like hotcakes. Everyone loved them!

• Amusing quips and poems on call sheets are always great.

• Most film crews don’t need much encouragement when it comes to having fun, so pools and contests are always good, as are potluck dinners, kick-off parties or wear-an-unusual-hat day. On one of my shows, to honor the production coordinator (who was in his black turtleneck phase at the time and wore one every single day), we all surprised him by wearing black turtlenecks on the last day of shooting. We had a group picture taken of all of us in our turtlenecks, and I smile every time I think of it.

• My friend Phil Wylly, during his production-managing days, wrote the funniest memos I have ever seen. He always got his point across and was able to entertain you at the same time. The titles of the memos alone are amusing. One was: “A Fate Worse Than Meal Penalty!”, and it dealt with the dreaded “Forced Call!” In an effort to make us all aware of exorbitant phone bills, he issued another one entitled, “The Enrichment of the Telephone Company.” And when asked to order a pig for a scene we were prepping, he wrote the following entitled “Pyramid Power.” It’s quite dated, but worth repeating and sharing:

Piglet = $25

Truck to carry = $50

Driver for Truck = $200

Wrangler to Tend Pig = $200

Gov. & Union Fringes @ 40% = $160

Location Meals for Driver & Wrangler = $12

Gasoline & Oil for Truck to Carry Piglet = $10

Total Cost for 1 Poor Little

Pig for 1 day = $647.00

p.s. Today, that same piglet for one day would cost approximately $1,200.

Also from Phil:

Tales from The Trenches

We were on stage, I think at Twentieth Century-Fox, ready to shoot a very sensitive scene: a husband and wife, seated in their modest kitchen, are grieving over their young daughter’s death. The set was quiet, the mood somber, everyone sensitive to the dramatic power of the scene about to be filmed. “All right, let’s try one,” the director said in a hushed voice. “Roll please,” the assistant director whispered. Then, from somewhere high above came the cooing sound of a large pigeon. The mood was broken. “Let’s cut,” the director said softly. We waited for a few moments. No more cooing. “Okay, let’s try again.”

Same result: “Roll please,” then came: COO COO COOO.

The director sent the actors back to their dressing rooms. We opened the stage doors and sent men with flashlights, sticks, bull horns, etc. up into the permanents to chase the bird. After half an hour or so we could see no further sign of the bird and assumed it had flown out. “Okay, let’s close things up and try again. Roll please. Action.” The husband reached out to take his wife’s hand … and PLOP! Right in the middle of the table, from high above, the pigeon let us know what he thought of the scene.

That night our director and writer reworked the scene to play in the living room. The next day, the general feeling was the scene actually played better in that set and, by the way, the studio manager gave us credit for the lost stage day.

The moral of the story: Sh*t happens, so be prepared for anything!

I’d like to acknowledge and thank Michael Coscia, April Novak, Kris Smith, Robbie Szelei and Phil Wylly for their contributions to this chapter.

FORMS IN THIS CHAPTER

• Call Sheet

• Production Report

• Daily Wrap Report

• Raw Stock Order Log

• Raw Stock Inventory

• Camera Department Daily Raw Stock Log

• Script Supervisor’s Daily Report

• Script Supervisor’s Daily Log