Chapter EIGHT

The Techno-Edged

Teflon, Tinsel, and Me

Were the 1980s a replay of the 1920s? The similarities between the two decades were remarkable. For the media, both decades were marked by technological advancement. In the 1920s radio technology advanced and television technology arrived; in the 1980s cable and satellites advanced and fiber optics, high-definition television, digital broadcasting, and other new technologies were introduced. In the 1920s the business of broadcasting grew by leaps and bounds and managed to survive the economic crash of 1929; in the 1980s the broadcasting business—including record sums for sales of properties as well as record advertising revenues—reached its highest peaks before the economic recession began at the decade’s end.

Both decades were eras during which the rich got richer and the poor got poorer. Wealthy stations got stronger; poorer stations fell by the wayside. Government turned a blind eye to unethical entrepreneurs who exploited their country—in one era, oil barons and bootleggers; in another, savings and loan operators and military contractors. Public officials violated the Constitution and federal laws with impunity. Teapot Dome scandals in the 1920s vied for infamy with Iran-Contra scandals in the 1980s. In both decades millions of people were plunged into poverty, hunger, illness, and homelessness. For most of the 1920s, broadcasting operated with no regulations requiring service in the public interest; in the 1980s, deregulation moved toward nonregulation. In the 1920s, responsible radio news was just beginning; in the 1980s, broadcast news was often criticized for abandoning its responsibilities and allowing itself to be manipulated by politics and politicians, making news more “infotainment” than information. If there were any Ed Murrows around in either decade, they were kept well hidden.

If the 1920s reflected the “I don’t care generation,” the 1980s were called the “me generation”—and both generations overindulged in a national orgy of spending. In the economic euphoria of both decades, the middle class ignored the huge national debt that it would one day have to pay off, the artificial prosperity that would end in joblessness and bank failures, and the tax laws that decreased the taxes of the upper-income groups while increasing the burden of lower- and middle-income tax-payers. In the early 1980s, the United States was developing a polarization that it had not experienced since the early 1930s, a déjà vu of profiteering and free-spending insensitivity that pretended that the less fortunate part of America didn’t exist. In most of its programming, broadcasting reflected and even encouraged that fiction. By the end of the 1980s, as in the 1920s, as broadcasting’s profits reached record heights, the economic bubble burst.

Both television and radio continued to grow in the 1980s. At the beginning of the decade 98% of the nation’s households had television sets, the highest figure the medium would reach. Cable had 20% penetration. Although fewer than 100 new AM radio stations had gone on the air during the previous five years, more than 650 new FM stations were in operation, for a total of 8,750 radio stations, including 763 noncommercial FMs. Television had begun to reach its saturation point, with only 28 new commercial and 30 new noncommercial stations in five years; nevertheless, for the first time they added up to more than 1,000 TV stations on the air. Soon another dimension would be added as the FCC authorized the development of low-power television, which by the end of the decade would have more stations on the air or with more construction permits than full-power TV. Television advertising revenue had more than doubled in the previous five years, to almost $11.5 billion; radio advertising had almost doubled in the same period, to more than $3.7 billion. FM continued to do better than AM; in 1980 it captured 52.4% of the total national radio audience age 12 and over.

Home Ownership of TV Receivers, 1946–1980

| YEAR | HOUSEHOLDS WITH TV (%) |

| 1946 | 0.02 |

| 1950 | 9.0 |

| 1955 | 78.0 |

| 1960 | 87.0 |

| 1965 | 93.0 |

| 1970 | 95.0 |

| 1975 | 97.0 |

| 1980 | 98.0 |

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census.

The nation’s highest-rated television program was a prime-time soap opera, Dallas. It hit its peak in 1980—two years after its debut—when more than 41 million homes tuned in to see one of the most hyped single episodes in television history—“Who Shot J. R.?” It received the highest numbers for any individual show up to that time, a 53.3 rating and a 76 share. The second most watched TV weekly show was a news feature, 60 Minutes. In the early 1990s Dallas ended its long run; 60 Minutes was, and is, still going strong.

TV viewers saw new personalities in 1980. Walter Cronkite, the “uncle” of network news anchoring, retired, and Dan Rather succeeded him at CBS. Roger Mudd, who had wanted that job, accepted the same position at NBC. ABC countered with an expansion of topics on a late-night news feature program that had begun the year before with special reports on the Iran hostage crisis; in 1981 the program would officially be titled Nightline, with Ted Koppel. The longevity of all three news personalities in their jobs suggests that the networks had made good choices.

While variety and music programs had all but disappeared from television, radio had settled deeper into its specialized music programming formats. A number of different types of rock stations, for example, could be found in almost every market, sharing highly fractionalized and targeted audiences.

On the technical side, the commercial TV networks followed PBS’s lead and instituted closed captioning for people with hearing impairments. On the business side, RCA and CBS made a deal reminiscent of the early days of radio: CBS was licensed to produce and distribute videodiscs using RCA’s SelectaVision system.

In this last year of the Carter–Ferris FCC, the commission mixed hard regulation with deregulation. It rescinded the licenses of three RKO TV stations—WOR (Newark), KHJ (Los Angeles), and WNAC (Boston)—because of business misconduct by RKO’s parent company, General Tire and Rubber. The decision sent shock waves through the broadcasting industry, which felt that now the children were being held responsible for the sins of the parents.

The FCC also changed clear-channel designations for certain day and night stations, causing havoc for some and increased opportunities for others. It began a telco inquiry, a matter still debated in the 1990s. Telco is simply an acronym for telephone company and refers to the issue of telephone companies seeking the right to own and operate cable systems in communities where they also provide telephone service. Broadcasters and cable operators grew increasingly wary of telcos throughout the 1980s because of their potential as both delivery services (using fiber optics) and information entertainment providers. In the early 1990s, telcos could not engage in area-of-service activities beyond those of supplying common carrier services to companies that wanted to provide programs; but federal court and FCC rulings in 1991 suggested that telcos might soon receive cable operation authorization, which ultimately they did.

Beginning in the late 1990s, once-strict restrictions on telcos’ provision of news or entertainment programming in their main area of (telephone) service were relaxed in an effort to promote intermedia competition. Critics argued that such changes merely strengthened the monopoly position of the four surviving Bell regional operating companies.

During 1980, following intensive investigation, the FCC staff drew up a report and recommendations on the Reverend Jim Bakker and his PTL television network. Violations of many FCC rules, including the filing of false reports and the defrauding of viewers, made it clear that Bakker’s licenses could be revoked, that he would be subject to fines, and that he was open to prosecution by the Department of Justice. The FCC order was ready to go. But for some reason FCC Chairman Ferris decided not to go ahead with the action and instead let it carry over for President-elect Ronald Reagan’s FCC to deal with in 1981. Yet the Reagan FCC did nothing about it, either. Coincidentally, it was reported that Bakker and some of his colleagues had contributed heavily to the Reagan campaign. It wasn’t until the late 1980s that action finally was taken against Bakker.

The FCC’s pre-Reagan deregulatory efforts in 1980 included the ending of requirements for a number of station reports and filings and the abolition of two of its offices, the Office of Network Studies, which for years had been a watchdog on network-station relations, and its Educational (Public) Broadcasting Branch, which had served as the facilitator and advocate for the growth of public broadcasting and other educational-oriented media services within the FCC. A federal district court upheld an FCC order that modified the syndex (syndicated exclusivity) rules; the order permitted cable systems not to black out “significantly viewed” distant signals that duplicated the programs of local stations. A few months later the FCC repealed the syndex rule entirely. The U.S. Court of Appeals stopped FCC implementation of the repeal, pending its consideration of the case; the following year, 1981, it upheld the FCC’s ruling. (In 1990 the syndex rule was reinstated.)

Yet as Al Jolson, were he still alive, might have said, “You ain’t seen nothin’ yet.” In November Ronald Reagan was elected President decisively over Jimmy Carter and an era of deregulation moving toward unregulation was at hand.

1981

The year 1981 began with a deregulation bang. President Reagan’s nominee to chair the FCC, Mark Fowler, was expected to immediately implement the new President’s marketplace philosophy and deregulate the broadcasting industry, to “get the government off broadcaster’s backs.” In the several months that it took him to be confirmed by the Senate, two predecessors paved his way.

First was, as Broadcasting magazine wrote, “the laissez-faire legacy of Charlie Ferris.” The Carter FCC chair, a Democrat who had been expected to represent the public interest, had been attacked by public interest citizen groups at various times during his years as head of the FCC because of his deregulatory policies. Ralph Nader, for example, denounced the FCC under Ferris as one of the worst agencies in Washington. Second was Robert E. Lee, a forthright conservative Republican, who was in his 28th year as an FCC commissioner—the longest tenure of anyone on a federal commission, surpassing Rosel Hyde’s 23 years on the FCC when Hyde retired in 1969. Lee planned to retire later in 1981. He was first named interim chairman, then chairman, until Fowler’s arrival in May.

Ferris and then Lee oversaw the following FCC deregulatory actions in the first four and a half months of 1981:

• Radio was deregulated, its public service programming requirements discontinued.

• Radio was allowed to exceed 18 minutes per hour of commercial time.

• Applications for license renewals were shortened to the size of a large postcard,

• replacing forms and reports designed to make a station show it had operated in the public interest during its preceding license period.

• Third-class radiotelephone licenses were abolished.

• “Ascertainment of community needs” requirements for radio were dropped.

• Program log requirements for radio were rescinded.

• Public broadcasting stations were permitted to broadcast logos and identify products of underwriters.

Within months after Fowler took over, the FCC asked Congress to revise the Communications Act to eliminate the comparative renewal process, eliminate the “reasonable access” provision of the equal time rule, repeal the requirement for equitable distribution of radio service throughout the United States, and initiate other changes that would make the marketplace rather than the government the regulator of broadcast services. Although Congress was not cooperative, during the next few years Fowler managed to accomplish virtually every one of his deregulatory goals. In 1981 Congress extended the license period for radio stations from three to seven years and, for television stations, from three to five years. The U.S. Court of Appeals ruled that scrambled pay-TV signals were protected and that any user must obtain permission and pay whatever fee was required to unscramble and use such signals. The Supreme Court opened courtroom doors to electronic journalists by ruling that states could—but were not required to—allow broadcast coverage of criminal trials, even if the defendant objected.

Some 1981 news coverage showed how effective broadcast journalism could be. One of the biggest stories was the release of the American hostages in Iran, even as Ronald Reagan was being sworn in as President. Later in the year, five ENG cameras were in operation as the nation saw live the attempted assassination of President Reagan. Broadcasting also covered fully the assassination attempt on Pope John Paul II.

Entertainment programming made new paths in drama and music. Hill Street Blues began on NBC, its in-depth, slice-of-life story lines reminiscent of the Golden Age of television drama but with more characters and episodic continuity. It would revolutionize TV drama formats. And MTV was born, not only providing teens with countless new hours of TV viewing and Michael Jackson with countless moonwalks but also helping shape video and film content and style, as well as other aspects of society, for years to come.

Fig 8.1 For many young people, MTV was the most important television innovation of the 1980s.

Courtesy MTV Networks.

A new high for viewing was reached in 1981, with an average of 6 hours and 36 minutes per day per household. More people watched and listened to more television and radio stations than ever before; the total on the air broke the 10,000 mark by the end of January 1981.

Some people, however, were unhappy with television’s programming. The Reverend Donald Wildmon and his organization, Coalition for Better Television, threatened to boycott advertisers who continued to support programs Wildmon and his group deemed offensive. The increasing conservatism of the times encouraged the growth of this and other groups similar to the already powerful Moral Majority.

The business of broadcasting boomed. Mergers of media giants, takeovers of communications companies, and buying and selling of stations escalated. One 1981 sale represented the largest price paid up to then for a single station: $220 million from Metromedia to Boston Broadcasters, Inc., for WCVB-TV in Boston. The largest merger in cable TV up to then also took place: Westinghouse Broadcasting Company bought TelePrompTer Corporation for $646 million. The recorder of the business of broadcasting, the bible of the industry, Broadcasting magazine, also celebrated; it was its 50th birthday. Time and people passed: Robert E. Kintner, the former president of NBC and ABC, died, as did Marshall McLuhan, the guru of mass communications.

Public broadcasting was now well established, with yearly budgets from Congress and with a strong structure in CPB, PBS, and NPR. Having done its job of promoting the development of the system, including the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967—perhaps too well for its own survival and unable to adapt creatively to the new noncommercial broadcasting structure—the NAEB, which had been formed in 1934 and traced its roots back to 1925, went out of existence.

Technical innovations continued. The first professional one-piece camcorders went on sale. The Japanese HDTV system was demonstrated in the United States, initiating the beginning of a dramatic change in the U.S. system. Although not then associated with the living-room television set but to have a profound effect on U.S. communications within a few years, the first IBM personal computer, or PC, became available.

Broadcasting reported both belligerence and humility. Ronald Reagan started his Presidency by escalating the Cold War, threatening to nuke the U.S.S.R. (in an offhand remark at an open mic prior to a radio address). By contrast, he ended his Presidency by making an accommodation with the U.S.S.R. and helping bring the Cold War to a close. Nuclear conflict was the last thing the American public wanted as it soberly remembered its last war with the 1981 unveiling of the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C.

MTV

Everything changed when cable came along. Prior to cable, which more than doubled its household penetration to nearly 60% during the 1980s, Americans had lived in a network broadcasting era in which there was a single popular culture served by the few major radio, then television networks. From 1920 through the 1980s, the broadcast era was something unprecedented in human history, a culture that had nearly everyone sharing the same media fare. Cable changed that dynamic by breaking up the audience into many popular cultures (now called “niche” audiences), with each faction sharing experiences different from those of other segments of the population. At first audiences were reluctant to abandon free television for the unproven content of cable. But that changed on August 1, 1981, with the launching of Music Television (MTV) and its prophetic first song, “Video Killed the Radio Star.” MTV produced a generation of screeching kids echoing the channel’s mantra of “I Want My MTV,” for whom cable would become an absolute necessity. Kids needing their daily dose of artists like Michael Jackson, Culture Club, and Duran Duran harassed their parents into getting their homes wired and may have, more than any other single factor, made cable a necessity.

1982

In 1982 the FCC removed its limits on commercial time per hour for television. It abolished its three-year trafficking rule, which had prevented a station from being resold within three years after its acquisition. This rule had been designed to prevent stations from being bought and sold for immediate profit taking, thus neglecting programming or other operations in the public interest. As noted earlier, the FCC authorized AM stereo in 1982. Yet the commission refused to designate one of the five approved systems as the standard, thereby leaving AM stations waiting for an eventual marketplace determination. Subscription television was deregulated. Some public TV stations were given special authorization to experiment with actual advertising.

The FCC also authorized DBS, but implementation, other than short-lived experi-ments, was a long way off. The commission began accepting applications for cellular radio. And low-power television (LPTV) stations, which had been authorized earlier, began going on the air, with large numbers of applications for more pending. Congress amended the Communications Act to reduce the number of FCC commissioners from seven to five.

A combined government–industry deregulatory action was the abolition of the NAB’s radio and television codes for programming and advertising. After the courts, following a Justice Department suit, found part of the NAB’s advertising code unconstitutional, the NAB hastily dropped all its codes, including its guidelines for children’s programs.

Perhaps the most significant implementation of an earlier FCC-prompted action was the settlement of the Department of Justice’s suit against AT&T, divesting AT&T of all its local telephone companies, effective in 1984. AT&T would, in return, receive permission to enter other new technology fields. Although many public interest groups hailed the breakup of Ma Bell as a step forward in reducing industry monopolies, it would take years to resolve some of the immediate problems of chaos, inefficiency, and higher costs. Another government action related to broadcasting was a report by the National Institute of Mental Health, Television and Behavior, which found that televised violence did affect some viewers’ behavior.

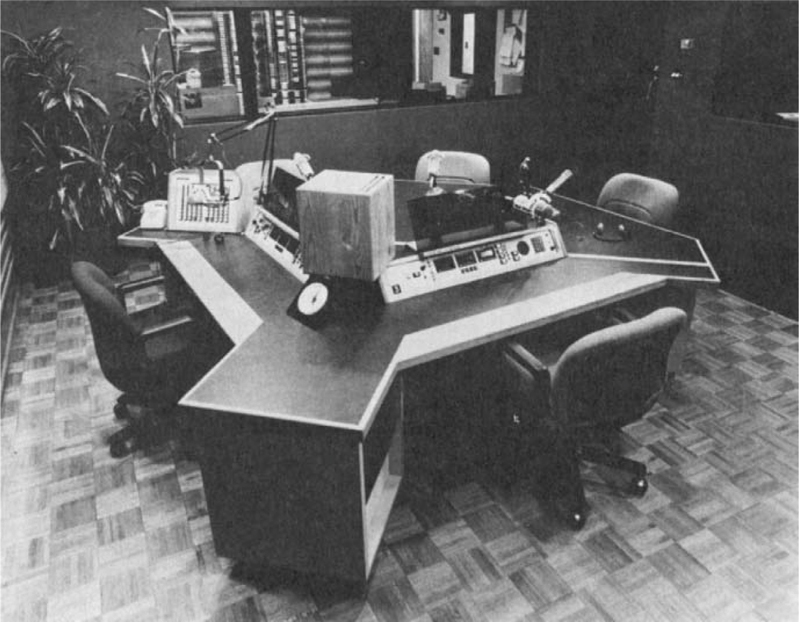

Fig 8.2 In the 1980s AM broadcasters saw stereo as a way to gain parity with FM.

Courtesy KDES, Palm Springs, California.

While violence may have come from some television programs, violence was done to one. Ed Asner, star of the Lou Grant show, which had for some years been successful artistically and in the ratings, became politically controversial when he participated in raising funds for medical supplies for rebels fighting the dictatorial government of El Salvador. He was attacked by politically conservative sources, including the Moral Majority and the actor Charlton Heston, who had recently been beaten twice by Asner in bitter fights for the presidency of the Screen Actors Guild. Pressure was put on advertisers, and several withdrew from the show. Although the show’s ratings had begun to decline, they were still highly respectable; nevertheless, CBS decided to cancel the program anyway. Asner himself later stated he did not liken this situation to the blacklisting of the 1950s; now it seemed sufficient simply to be controversial.

PAULA LYONS

CONSUMER EDITOR, WBZ, BOSTON; FORMER CONSUMER EDITOR, ABC’S GOOD MORNING AMERICA

Great moments in television cannot be planned. They just happen! One happened to me back in 1982. It was a typical scenario. A housing company had taken deposits from consumers, promised to put up manufactured homes on specified lots of land in Southeastern Massachusetts, and never delivered. I was on the empty lots about to interview three of the aggrieved couples when a representative of the housing company showed up, with a customer, trying to sell the same lots all over again! The victims I was about to interview went crazy! They attacked the saleswoman and the new customer—verbally—warning the customer not to be the next chump. And for a moment I wondered, What is my role? What do I do here? And the answer was nothing, nothing at all. The photographer kept rolling. The argument was a beaut! And I ended up with a piece of award-winning television!

Courtesy Paula Lyons.

Fig 8.3 Paula Lyons.

Courtesy Capital Cities/ABC, Inc.

While Lou Grant went off the air, two new shows that went on the air were to make their marks. St. Elsewhere, though never a ratings leader, was praised over the years for innovation and funkiness. Cheers became a national institution and until it went off the air in 1992 was still at or near the top of the ratings every week.

In seeking higher ratings, ad agencies began to stress an additional aspect of market research. Going beyond demographics, they now worked with “psychographics” as well, seeking to determine attitudes and beliefs as well as age, gender, and affluence of viewers and prospective purchasers.

Cable continued to expand, now reaching 29% of all homes, and nonentertainment channels such as C-Span and the Home Shopping Network appeared.

Another broadcast pioneer, RCA’s longtime star inventor, Vladimir Zworykin, who had vied with and lost out to Philo Farnsworth for the title of father of American television, died at age 94.

1983

Less regulation and more technology dominated 1983. The FCC allocated eight Instructional Television Fixed Service (ITFS) channels to MMDS and was deluged by thousands of applications for the commercial service. The commission decided how to determine to award new LPTV licenses—not on the basis of proposed service to the public but by lottery. The FCC authorized teletext—visual data that can be ordered for transmission to an individual television screen—but, as it did with AM stereo, refused to designate a standard. Previously authorized videotex—two-way interactive television, computer coordinated—was experimented with in two communities.

The FCC watered down the political equal-time rule. It permitted stations to set up their own political debates, thus allowing a station to include those candidates it favored and to exclude those it didn’t. That, and the relaxing of the definition of news—exempt from the equal-time rule—also made it possible for a station to carry news features and news interviews with candidates it favored and to virtually rule out of contention, by lack of exposure, those it didn’t. This situation gave broadcasters unprecedented influence on local and state elections, especially party primaries having a number of candidates. Broadcasting’s control of the U.S. political process was virtually complete.

Fig 8.4 VCRs and CD players became the hottest new home entertainment technologies in the 1980s.

Courtesy TEAC.

In a policy statement regarding children’s television, the FCC once again refused to issue any rules; rather, as it did in its 1974 policy statement, it recommended voluntary self-regulation by the industry.

ABC, CBS, and NBC radio network feeds went satellite. Compact disc players, with considerably better sound quality than long-playing records or tapes, began to make inroads in the home audio market—though it wouldn’t be until 1987 that full marketing of an improved version would take the country by storm. The shift from analog to digital radio began, and there was much talk about digital television and HDTV in the near future.

The amazing ratings success of Roots continued to prompt more network television miniseries, including The Winds of War, which set a new record for numbers of viewers, and The Thorn Birds. The MacNeil Report, which had been on the air since 1976, enhanced PBS’s status as it became The MacNeil-Lehrer Report. The final episode of M*A*S*H was a 2.5-hour special, garnering the largest audience up to that time for a single program, a 60.3 rating and a 77 share.

A 1983 special generated overtones of 1950s McCarthyism. The Day After was a docudrama portraying what might happen were there an atomic war. The early 1980s were a time of antinuclear protest and a national nuclear freeze campaign, reminiscent of the anti–Vietnam War protests of more than a decade before. The Day After was labeled unpatriotic, even Communistic by some groups, and, coupled with its graphic depiction of nuclear effects, it was highly controversial by the time it aired. Indeed, there were rumors that it might not be shown at all. ABC, which showed courage in airing it, added a disclaimer, and a panel discussion followed the program. Rating surveys showed that more than 50% of potential adult viewers saw The Day After. For some, the horrors it presented were devastating; for others, it didn’t go far enough.

Controversy attended NBC’s miniseries Holocaust as well. It presented, also in docudrama form, what happened to a Jewish family in Germany before and during World War II. Here, too, some viewers felt that the program opened wounds that should have remained closed; others felt that it should have done more to prick the consciences of those who permitted the Holocaust to happen and of a current generation that might forget its lessons.

Station sales set one record after another. No sooner did TV station KTZA in Los Angeles sell for a record $245 million than KHOU-TV in Houston sold for $342 million.

Ethics raised its disturbing head in 1983. In Alabama, a camera operator for WHMA filmed a man who set himself on fire; the cameraman did so rather than interceding and possibly saving the man’s life. The question of the journalist’s role in such situations continues to be discussed today. In Kansas City, a former TV news anchorwoman, Christine Craft, was awarded $500,000 by a jury in a sex-discrimination suit that found Craft’s firing had been based on physical looks—she allegedly didn’t look young and pretty enough—and not on competence. Although the decision was later reversed, Craft’s courage in standing up against gender bias at the potential cost of her future career motivated many other women in broadcasting to stand up for equal opportunities and their personal rights. The treatment of Christine Craft was counterpointed that same year with media coverage of the treatment given another woman, Dr. Sally Ride. Based on ability and performance, Ride became the first American woman astronaut in space.

TV’s Versions of The War of the Worlds

Following the 1938 The War of the Worlds broadcast, the FCC banned pseudo radio newscasts. But the format had a go on television with little public uproar or comment by the FCC. NBC’s 1983 Special Bulletin opened with benign promos on the fictional RBS Network before an ominous graphic “Special Bulletin” appeared. What followed was a faux newscast detailing antiwar terrorists holding a homemade atomic bomb outside Charleston, South Carolina, demanding the government disable its nuclear stockpile. The program followed events as though it were an actual newscast, shot on videotape, stumbling dialogue, and frequent technical glitches, all enhancing the “live” feel. But television permitted on-screen scrawls noting that the show was fictional. Still there were isolated reports of panic as some made snap judgments on what they were seeing between disclaimers. And as we learned from War, those affected failed to make a simple “reality check” by flipping the dial to see what other stations were covering. In a similar vein, CBS’s 1994 Without Warning featured a “live” news break-in during an ostensible network movie, reporting on an unfolding alien invasion, and as homage to Orson Welles, also airing on Halloween eve in the same fictional village of Grover’s Mill but this time situated in Wyoming.

1984

Cable’s deregulatory turn came in 1984 as Congress passed the Cable Communications Policy Act of 1984. Rates for subscribers were no longer limited to those agreed to in franchise contracts, and within a few years they shot up 50%, 100%, and more in many parts of the country. Percentages of gross revenue fees to cities previously agreed to between cable systems and cities were no longer valid, and a cap of 5% was set. Access channels no longer had to be provided free. These specifications and other amendments to the Communications Act gave cable additional freedoms to compete more effectively against broadcasting. Within five years, complaints from cable subscribers nationally—complaints predominantly related to service and rates—prompted Congress to begin work on a cable reregulation bill. Threats of a veto by President George H. W. Bush, however, caused Congress to drop cable legislation in 1990, though it was expected that some kind of cable reregulation would nonetheless occur in the early 1990s.

Another controversial action in 1984 was the FCC’s relaxation of the multiple-ownership rule to allow any one entity to own up to 12 TV, 12 AM, and 12 FM stations nationwide—an increase from 7–7–7. The original rule was adopted to “maximize diversification of program and service viewpoints as well as prevent any undue concentration contrary to the public interest.” Congress, however, was concerned with the extension of media monopolies and information control, and a series of compromises between Congress and the FCC resulted in a 25% cap on the total U.S. population any one TV conglomerate could reach. Exceptions were made for the maximum number of stations for minority owners, and population percentages were discounted for UHF stations. The new “Rule of Twelves” went into effect in 1985.

The deregulation of ascertainment, program logs, public service, and other requirements for commercial radio of a few years before went into effect for television and public broadcasting in 1984. Although broadcasters saw these FCC rulings as a boon, over their shoulders they saw other developments with which they were not happy. One was a Supreme Court decision in favor of Sony, reversing the finding of a lower court. The high court ruled that it was legal for a VCR owner to copy programs off television. For the two preceding years, that activity had been illegal. The 15 million U.S. VCR homes that had been doing so had, in fact, violated federal law. But, of course, such criminal actions—which they technically were—were impossible to monitor. Technical developments included the arrival of the first digital videodisc recorder, the first HDTV recorder, for sale by Sony.

In television programming, The Cosby Show came to NBC. It immediately became a national favorite and in the early 1990s was still near the top of the rating charts. With one of the few nonstereotyped portrayals of a middle-class black family—the father was a physician, the mother an attorney—The Cosby Show was lauded for establishing highly positive role models.

In radio, specialized music formats in some markets began to lose ground. By the end of the year a number of stations had revived the Top 40 format (by now referred to as Contemporary Hit Radio, or CHR), with its emphasis on personalities (Rick Dees and Scott Shannon, to name a couple of CHR superjocks) as much as on the music. It recalled for some listeners the 1960s, when such deejays as Alan Freed, Cousin Brucie, Wolfman Jack, and Murray the K reigned over the audio airwaves.

The power of advertising took an unusual turn when the TV commercial slogan for Wendy’s fast-food chain—“Where’s the beef?”—spoken by an 80-year-old performer, Clara Peller, became a critical catchphrase in the 1984 Democratic Presidential primary. One candidate used the slogan to denigrate another candidate. In the Presidential campaign, especially at both party conventions, satellite news-gathering (SNG) equipment made possible more thorough television coverage than ever before, permitting individual broadcast stations and cable networks like CNN and C-Span, as well as broadcasting networks, to report. It was in this campaign that special attention and probing were given to the first female ever to be on the Presidential ticket of a major party—Geraldine Ferraro, the Democratic Vice Presidential candidate.

Whereas broadcast journalists received full cooperation from political parties, they didn’t fare so well with the military. The military, having learned from television coverage of Vietnam that one should not let the public know what it is doing if the public might not like it, barred the press from covering the U.S. invasion of tiny Grenada. Only after several days were news teams allowed in. Such control and censorship of the press would reach a peak less than a decade later in the Persian Gulf.

1985

This was the year of the networks. In 1985 GE announced it was buying RCA and, with it, NBC, for $6.5 billion (the sale was completed in 1986). Ownership had come full circle since 1919, when GE established RCA to operate radio stations so that GE could remain solely on the manufacturing side of the business. Also in 1985, ABC was purchased by Capital Cities Communications for $3.5 billion. The Mutual Radio Network was sold to Westwood One for $39 million. CBS almost had a new owner, too, but Ted Turner’s bid to buy up controlling stock in the network failed. Rupert Murdoch purchased six television stations from Metromedia for $2 billion and formed a new network, Fox, which began operations the following year. Even cable got into the act, with the formation of a new network conglomerate, Viacom International, buying the Showtime, Movie Channel, MTV, and VH-1 cable networks for $690 million. To top it off, the networks took to the sky, transmitting programs by satellite to their affiliates.

Under deregulation, television licenses continued to increase in monetary value, and Tribune Broadcasting paid a record $550 million for one station, KTLA, in Los Angeles. Television advertising revenues nationally had zoomed almost 100% since 1980, to surpass $20 billion annually. Radio’s five-year increase was more modest by comparison, under 90%, but reached an annual total of $6.5 billion. The number of AM stations increased only 10%, to 5,973; commercial FM stations went up just a bit more than 15%, to 3,282; and noncommercial FM up less than 5%, to 797. Commercial TV stations increased by fewer than 150, to 883, and noncommercial TV stations by only 37, coming close to their saturation point, for a total of 314. Cable saw accelerated growth and was now in almost 40% of U.S. television homes.

Programming was eclectic, as varied new sitcoms such as The Golden Girls, the first pay-per-view cable service, and national distribution of the Home Shopping Club. To some, the most significant program of 1985, and the one with the largest audience, was the “Live Aid” concert from Philadelphia and London featuring the leading popular music performers of the time. Fourteen communication satellites carried the program to more than 1,200 countries and by tape delay to almost 50 more. “Live Aid” was watched by as many as 400 million people worldwide. It raised about $75 million for relief to famine-stricken lands (see Tony Verna in the next chapter).

Syndication of video programming grew for a number of reasons. More network programs became available. The increasing number of cable networks and new, independent television stations, including LPTV operations, required more program material. The increased use of satellite and other new technologies facilitated program distribution.

A most important court decision regarding a regulatory matter shook the broad-casting industry. In its 1972 cable rules the FCC had asserted the “must-carry” principle, whereby cable systems were obligated to carry all local broadcast signals—“local” defined as stations within a 60-mile (later 50-mile) radius. Quincy (Washington) Cable Television and Turner Broadcasting (which wanted less competition from local signals in order to facilitate carriage of its Atlanta “national” station) had brought suits against the FCC on the grounds that the must-carry rules were unconstitutional. The U.S. Court of Appeals found that the must-carry principle did violate the First Amendment. A subsequent attempt by the FCC to institute a must-carry provision was also ruled unconstitutional. Finally, agreement was reached (1) requiring carriage only of public television signals, based on cable system capacity, and (2) providing subscribers, at a fee, with A/B switches whereby a subscriber could switch from cable to off-the-air reception if the cable system were not carrying a local broadcast signal the subscriber wanted to see. Although broadcasters’ worst fears were not realized, in fact a number of local stations were dropped by cable systems that could make more money by substituting a distant channel or an additional cable network. Some marginally subsisting television stations, with the loss of advertising revenue, did not survive. (For example, in a 50% penetration market, loss of cable carriage removed 50% of a station’s viewers except for those who used the A/B switch, in turn causing advertisers to withdraw or pay an equivalent discounted rate for commercials.)

Fig 8.5 In the 1980s pop-rock music stations enhanced their hold on audiences by sponsoring spectacular concert events.

Courtesy WLS, Chicago.

A sign of economic times yet to come was foreign competition, which in 1985 forced the RCA Broadcast Equipment Division—producers of broadcasting equipment almost from the beginning of radio—to close down.

The Twistings and Turnings of “Must-Carry”

The FCC first mandated must-carry rules in 1972, but it wasn’t until the 1980s that cable operators complained. With the growth of cable-only networks, operators, particularly those with limited capacity, felt they would be less marketable if they had to devote considerable portions of their space for stations consumers could receive free, over the air. Some operators offered subscribers an A-B switch in which one terminal linked to the cable and the other to the antenna but found viewers reluctant to leave the comfort of their couches to manually switch between cable and local feeds. Over the years the federal courts have frequently rejected must-carry on First Amendment grounds, only to have it resurface. The current version, known as retransmission-consent, is an odd arrangement wherein local stations can force carriage if they don’t request reimbursement, but if they do, even if it is some barter deal, the cable operator can refuse to carry. Must-carry more often affects independents and minor network affiliates that are at a program-popularity disadvantage. The problem has been further confounded with the transition to digital that offers broadcasters the ability to send multiple content streams but finds cable operators balking at how many they must carry.

1986

Hard times were coming to broadcasting, despite its expanded revenues. In 1986 all the networks, faced with increasing competition from cable, VCRs, and other home technologies and steadily losing prime-time audiences, reorganized under new ownership and/or changed leadership. They tried to become more business efficient by cutting back staff and paying more attention to the profit and loss columns. CBS, for example, which had been responsible for some of the key technical innovations in broadcasting, closed its technology center.

A television-linked service received a setback. The Knight-Ridder Company’s experiment with videotex in Miami, Viewtron, closed down with a loss in excess of $50 million. Five years later videotex still had not yet made expected headway, although the number of videotex services and subscribers was growing.

Pay-cable companies tried to protect themselves from piracy. Led by HBO and Cinemax, most pay-cable channels were, by the end of the year, scrambling their signals. Illegal decoders and unscramblers were easily available, however, even through mail-order services, and many were sold.

Despite the problems, TV viewing was the highest it had ever been, an average of 7 hours and 10 minutes per day per home. A spate of Cosby-clone sitcoms hit the air. Few of them survived. A successor to Hill Street Blues did: From one of the same creators, Steven Bochco and Terry Louise Fisher, but set in a law office and courtrooms instead of in a police station and patrol beats, L.A. Law started high on the charts and stayed there.

A bright spot for network television was sports. Live coverage drew larger and larger audiences each year, with advertising revenues to match. By 1991, for example, a 30-second commercial on the National Football League Super Bowl broadcast cost $800,000.

Technical advances stressed the coming digital revolution, including continued development of digital audio tape (DAT), laser videodiscs with digital sound tracks, and digital TVs and VCRs. A number of new satellites were launched for the principal purpose of reporting. SNG was now an essential part of broadcast journalism. The importance of cable news as an alternative to broadcast news was demonstrated when the space shuttle Challenger blew up shortly after its launch from Cape Canaveral. Only CNN was covering the event live, although the network news teams came in almost immediately after the disaster.

The year 1986 was the beginning of the end for the Fairness Doctrine. Controversial since its development through the Mayflower decision and the Red Lion case, its demise was urged by most broadcasters, who believed it violated their First Amendment rights by restricting their privilege to say what they wanted on their stations without the government requiring them to present opposing viewpoints. Its retention was urged by those who believed that rather than restricting freedom of speech and ideas, it made them more available for a broader U.S. constituency—those who, under the Fairness Doctrine, had an opportunity to put them on the air and those who heard views they would not otherwise have heard. FCC Chairman Fowler, implementing President Reagan’s marketplace philosophy, had stated that one of his priorities was to abolish the Fairness Doctrine.

The doctrine’s opponents got their chance, ironically, because the FCC upheld a Fairness Doctrine complaint brought by the Syracuse (New York) Peace Council against the Meredith Broadcasting Company station, WTVH, in Syracuse. WTVH was found to have denied the council time under the doctrine to respond to false statements by the station regarding a controversial Syracuse nuclear power plant referendum. In a sequence of events from 1986 to 1987, Meredith Broadcasting refused to honor the FCC’s invocation of the Fairness Doctrine and took the case to court. The U.S. Court of Appeals, in a 2–1 vote, decided that there was no statutory Fairness Doctrine requirement and that the commission did not have to implement it. (The two votes against the doctrine, coincidentally, were by Justices Anthony Scalia and Robert Bork, both of whom would be nominated to the Supreme Court by President Reagan, the former to be confirmed, the latter not.) Congress then passed a Fairness Law, codifying the doctrine. President Reagan vetoed it, and although the veto would have been easily overridden in the House, the Senate count indicated it would be one or two votes short. Congress therefore let the veto stand, whereupon the FCC abolished the Fairness Doctrine.

Fig 8.6 As cable entered more and more homes in the 1980s, concern that children would have access to adult-oriented programming prompted systems to offer “lock-box” features to subscribers.

1987

When Mark Fowler left the FCC in January 1987, he had put through virtually every deregulatory action he had promised. The major action not yet completed was that of the Fairness Doctrine, which was not officially eliminated until later in the year. But during his almost six years as FCC chair, Fowler’s record was impressive (that is, if you were pro-marketplace; it was depressive if you favored public interest regulation). During Fowler’s stewardship the commission took the following actions:

• Authorized AM stereo without setting a standard

• Dismissed a proposal requiring divestiture of colocated AM-FM stations owned by the same licensee

• Eliminated filing of annual financial reports by broadcasters and cable operators

• Shortened station application and transfer of ownership forms

• Authorized paid, promotional announcements for nonprofit groups by public broadcast stations

• Eliminated the three-year antitrafficking rule

• Authorized MMDS while taking away ITFS channels

• Eliminated the requirement that a station ID be that of the community of license, thus permitting station identification with any community

• Exempted cable systems from rate regulation of tiered services

• Modified the equal-time rule to authorize broadcasters to hold their own political debates

• Eliminated most of its regulations regarding station call signs

• Eliminated a “regional concentration” rule that prohibited ownership of three stations when two were located within 100 miles of the third

• Relaxed the policy even more for children’s TV, giving producers full leeway

• Broadened multiple-ownership limitations from 7–7–7 to 12–12–12

• Eliminated restrictions on AM-FM combinations’ duplication of programs

• Relaxed the policy of judging the character of an applicant for a station license

• Rescinded cable system requirements of compliance with technical-quality performance standards

• Permitted tendered offers and proxy contests in sales of stations

• Eliminated the “ascertainment of community needs” requirement for TV and public broadcasting (having done so for radio earlier)

• Eliminated commercial ad limits

• Shortened program reporting requirements

Whereas all these actions might be considered clearly deregulatory, a number of others during that period were deregulatory in that they opened the media to new technologies but regulatory in that they established new rules and regulations. With respect to these combined kinds of actions, the FCC did the following:

• Authorized LPTV

• Authorized DBS

• Authorized teletext

• Reduced satellite orbital spacing

• Applied criteria used for broadcasting in reviewing cable EEO practices

• Authorized TV stereo

• Permitted quadrupling of the nighttime power of local AM stations

• Gave daytime AMs preference in the FM application procedure

Fig 8.7 Talk studios have become more commonplace than deejay studios in AM radio.

Although deregulation was de rigueur, the FCC became a hard-nosed regulator with its indecency rules. Revived “topless radio” programs were the primary targets. Although unable to establish a specific definition of what it meant by “indecency,” “obscenity,” or “community standards,” the FCC stated it would not permit material that “depicts or describes, in terms patently offensive as measured by contemporary community standards for the broadcast medium, sexual or excretory activities or organs.” While not permitting obscenity at any time, the commission established what it called a “safe haven” for “adult” materials between midnight and 6:00 a.m., presumably when children would not be watching or listening. At President Reagan’s urging, the safe haven was removed by Congress in 1988, and a 24-hour ban went into effect. This was one of the few issues on which broadcasters and citizen civil liberties groups generally agreed: They opposed such restrictions. In 1991 the U.S. Court of Appeals ruled that the full 24-hour ban was unconstitutional, a violation of First Amendment protections of freedom of speech.

News grew. The industry-supported public information arm, the Television Information Office (which would be abolished in 1990), reported that twice as many network affiliates increased their news coverage as decreased it. There was much ado about one news event in 1987. When the CBS live telecast of the U.S. Open tennis championships ran over into The Evening News, anchor Dan Rather protested the sports-versus-news priority by walking off the set. The result? Six minutes of dead airtime for all CBS affiliates—and sharp criticism of Rather.

Game shows became the most watched syndicated programs. Talk shows hit new daytime peaks, with Donahue clones such as Oprah and Geraldo becoming highly successful. Music shows on cable continued to attract large youth audiences, a phenomenon much like Dick Clark’s music shows on television had been decades before. One widespread complaint about programming involved Ted Turner’s colorization of old movies his company had acquired when he bought MGM.

The technical development of digital and HDTV continued apace. A Boston Globe headline said, “Digital May Make FM Obsolete.” The expectation was that digital sound would be to FM what FM sound was to AM. Presuming that digital would become the standard for all radio stations, it was predicted that by the year 2000 AM and FM would be equal, necessitating entirely new structural and programming changes in the radio industry.

The FCC took a hard look at HDTV through a joint FCC–Industry Advanced TV Advisory Committee and through the industry’s own Advanced Television Systems Committee. The time was nearing when the FCC would have to choose between HDTV (high-definition television) and EDTV (enhanced-definition television). ATV (advanced television) is the generic term referring to any system of distributing television programming that results in better video and audio quality than the current U.S. NTSC standard of 525 lines. HDTV offers about twice the number of lines, with picture quality comparable to that of 35mm film and audio quality similar to that of CDs. EDTV refers to systems that are an improvement over NTSC but are not as good as HDTV. In 1990 the FCC determined that it preferred an HDTV system that could operate in the present broadcast television spectrum and be compatible with the NTSC system—that is, permitting existing sets to receive the new signal in the 525-line mode while the public gradually switched over to HDTV sets, similar to what was done when color TV was authorized in 1953.

DICK CLARK

PERFORMER AND PRODUCER

I’ve always striven for sincerity and believability on mic and on camera. In the old days when radio announcers used to listen to their voices with a cupped hand held over their ear, they were listening for deep tone and resonance. The most sought-after qualities in those days were authority and command. The male voice needed maturity and depth. Things have changed since then. These days, whether it’s a male or female voice, the quality that works best is naturalness—believability. One does not have to possess a super-mature, super-resonant voice to succeed. Since starting in broadcasting in the 1950s, I’ve tried to come across as a “real” person.

Courtesy Dick Clark.

Fig 8.8 Dick Clark’s career as a broadcast performer spans five decades.

Courtesy Dick Clark.

Broadcasting’s competition continued to grow in 1987: Cable and home video recorders were each in more than 50% of U.S. households, and the fourth network, Fox, officially started its program schedule. Throughout the 1980s, complaints about rating methods grew, not only from some of the public but from networks, stations, and advertisers. The ratings systems, including leading companies A. C. Nielsen and Arbitron, tried various new approaches. One of Nielsen’s was a “People Meter” that purported to determine who and how many were watching, not just what number of sets were tuned to what programs. The networks soon expressed dissatisfaction with the People Meter, which showed lower ratings for their programs than they thought they should have. Some critics stated that the networks were trying to ignore the fact that the competitive media had generated a steady increase in viewing for their own programs, with a concomitant serious drop in viewing of networks’ primetime schedules. In the early 1990s network prime-time viewing continued to drop, rating companies were still blamed, and an acceptable method of measurement had not yet been found.

The power of television was shown in its coverage of the Senate’s Iran-Contra hearings. The Contras were the U.S.-founded armed forces trying to overthrow the socialist government of Nicaragua. Some of the funds sent to the Contras were sent illegally, siphoned by government officials and others from illegal arms sales to the United States’ enemy, Iran. Lieutenant Colonel Oliver (“Ollie”) North was a major figure in these transactions. Was Lieutenant Colonel North a hero or an antihero? North, who admitted actions that many considered subversive of the democratic processes of American government and even traitorous to the U.S. Constitution, was nevertheless transformed into an instant hero by the media.

Also in 1987, another moment dealing with the history of broadcasting occurred: the American Museum of the Moving Image (film and television) opened in Astoria, New York.

Cable Television Systems, 1955–1987

| YEAR | NUMBER OF SYSTEMS |

| 1955 | 400 |

| 1960 | 640 |

| 1965 | 1,325 |

| 1970 | 2,490 |

| 1975 | 3,506 |

| 1980 | 4,225 |

| 1985 | 6,600 |

| 1987 | 7,900 |

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census.

1988

Technology continued to dominate broadcasting developments in 1988. Broadcasters looked at HDTV with increasing interest, as a way of helping the quality of their off-the-air signals compete with cable. The industry’s Advanced Television Systems Committee approved a 1,125-line, 60-Hz signal standard. The FCC’s new HDTV Advisory Committee met for the first time, with a commission directive that any HDTV system chosen must be compatible with receivers currently in use. HDTV innovations in 1988 included release of the first HDTV videocassette and production of the first HDTV movie.

Two potential threats to both television’s and cable’s current structures moved forward. First, AT&T demonstrated its latest development in fiber optics. Modulated by lasers, the beams provided a wider bandwidth and an excellent signal. Second, Congress passed a bill facilitating delivery of satellite signals to backyard dishes—television receive-onlys (TVROs).

Stereo advanced in one medium but struggled in another. More than a third of the nation’s television stations were now in stereo; however, only 10% of AM stations were in stereo, not all of them compatible. The FCC recognized AM’s problems by eliminating its AM-FM nonduplication rule, and within a year some 1,000 pairs of stations were duplicating programs. AM continued to try new formats to stay alive. The SUN Radio Network offered AM 24-hour, talk-information programming. FM moved ahead, concerned principally with what music format might provide a new edge; in 1988, the adult contemporary format topped the ratings.

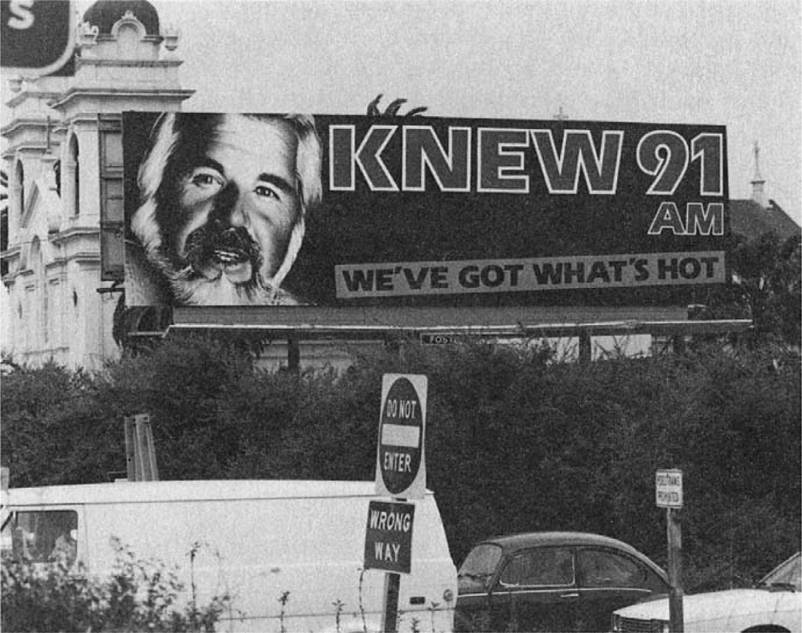

Fig 8.9 Radio stations—more than 12,000 strong—dot the U.S. landscape today.

Courtesy KNEW, Oakland, California, and Metromedia.

Television programming was a mixed bag. A 22-week writers’ strike forced cancellation of some series programs and compelled the networks to offer an “interim” fall schedule. The growing number of made-for-TV movies did well, and one miniseries, War and Remembrance, 18 hours in length, started in 1988, took a hiatus, and finished months later in 1989. “Trash TV” was in. Programs like Morton Downey, Jr.’s, with physical altercations provoked on the show, and Geraldo Rivera’s, in which the host actually got his nose broken during a fight on the program, drew large audiences.

Sometimes the news was almost as confrontational. While not Downey and Rivera, the U.S. Presidential candidate, George H. W. Bush, and journalist Dan Rather almost came to blows during a CBS interview. Bush and Rather “Spar Live on Network News,” headlined Broadcasting magazine. The last few months before the election gave the networks their final chances to cover President Ronald Reagan, whose television presence and “Teflon” image the networks continued to polish by emphasizing his positive actions, as in the excellent coverage given to Reagan’s summit meeting with Soviet President Gorbachev in Moscow. Broadcasters usually downplayed Reagan’s negative actions, such as his “I can’t remember” approach to the Iran-Contra scandal and his frequent “misspeaks.” The networks did, though, have one confrontation with the White House, which attacked them when all three declined to give the President prime-time coverage for a speech advocating aid to the Contras.

The election itself set off further criticism of the networks, principally from the public. The networks’ naming Bush and Quayle the winners even before all the polls closed resulted in calls for legislation mandating uniform voting hours nationwide. The networks were also accused of being the pawns of the politicians in going along with a highly negative Presidential campaign, including derogatory advertising against the Democratic nominee, Michael Dukakis, for which the Republican campaign director, Lee Atwater, apologized a few years later. The networks were criticized as well for allowing themselves to be manipulated by “spin doctors,” a phrase given to campaign officials whose jobs entail convincing journalists to give the “right” slant to stories about their candidates. Broadcast journalists seemed content to stress “sound bites” instead of issues and substance. Was it coincidence that public broadcasting stations won the most national Emmy Awards for 1988 news programs? Lawrence Grossman, the head of NBC News, urged television to be an “instrument of truth.” Was it also coincidence that, shortly afterward, he was fired?

Cable moved forward. Twenty stations copied Ted Turner’s WTBS and became superstations, reaching the entire country on cable via satellite. Turner added a new national station, Turner Network Television (TNT), designed to compete directly with the broadcast networks. Cable also added new, specialized channels, such as health and fitness. Pay-per-view grew, although the growth of VCRs did slow it down. Cable penetration and viewing went up, whereas prime-time broadcast viewing was down to 65%, continuing to drop steadily from its 90%-plus of not too many years earlier.

The regulators at the FCC, in the courts, and in Congress were busy. The FCC warned broadcasters about allegations of new payola scandals. It paid decreasing attention to citizen challenges to broadcast stations, renewing the licenses of a number of stations whose renewal applications had been challenged by the NAACP. In the courts, the FCC wasn’t doing as well as it would have liked to. In the preceding two years, 40 of its rulings had been overturned by the federal courts, ranging from must-carry provisions to policies regarding children’s TV programs. The FCC got what it wanted, however, from one negative court decision. A law initiated by Senators Edward Kennedy and Fritz Hollings had enjoined the commission from acting on a request from Rupert Murdoch for an extension of the waiver that would permit him to continue to own both a daily newspaper and a television station in the same communities, New York and Boston; such an arrangement was prohibited by the cross-ownership rules. A federal appeals court found the law unconstitutional. Murdoch challenged the cross-ownership rule itself in the courts.

Congress took a number of broadcast-related actions in 1988. It approved a rider by Senator Jesse Helms to the appropriations bill that established a 24-hour indecency ban, removing the midnight–6:00 A.M. FCC window for “adult programming.” Congress passed a bill limiting the amount of commercial time on children’s TV programs and requiring the FCC to consider informational and educational children’s programming at renewal time; however, President Reagan vetoed the legislation. In the House, Representative Edward Markey, chair of the Telecommunications Subcommittee, let the industry know that he would seek strong public interest regulation.

Fig 8.10 During the 1980s, UPI tottered on the edge of insolvency. It filed for bankruptcy in 1985 and, after restructuring, again in 1991.

Courtesy Irving Fang.

That didn’t deter the industry. Prices of stations continued to rise. However, not all was well: The stirrings of economic unease arrived as new owner GE began to break up the RCA radio-television empire, selling off parts of it in an economy move, radio going first. The NBC radio network was sold to Westwood One—which two years earlier had purchased the Mutual Radio Network—for $50 million (see Kenneth Bilby in the next chapter). ABC officials began to worry when ABC’s investment in covering the Olympics turned out badly—a loss of $50 million. The media were still solvent, however, at least according to the value of communication properties. Telephone companies were worth a total of $240 billion; cable, $90 billion; and broadcast television, $40 billion.

1989

Broadcasting began to worry seriously in 1989. For some time, networks had been tightening staff costs through attrition and layoffs. Advertising revenue had dropped in 1988; in 1989 it stayed just about even. This was unusual for an industry that for years had seen commercial revenues rise at rapid rates. A combination of the economy and cable competition made it a difficult time. Some cable companies had begun to put commercial programs, such as syndicated sitcoms, on their local origination channels, directly challenging local broadcast stations. In 1990 the Rochester, New York, cable system programmed a half-hour local daily news show, competing head to head with broadcast stations having the same type of program at the same hour for the community’s available ad dollars. A national survey found that viewers rated cable program quality and diversity higher than those of broadcasting. Broadcasting initiated an extensive “free-TV” campaign.

While some belt-tightening occurred, expansion also took place. Westinghouse bought 10 group radio stations for a record $360 million. The merger of Time and Warner created the world’s largest media company, renewing concerns about industry monopoly. One approach taken by producers to expand their businesses was to seek more international coproduction, thus simultaneously cutting costs and opening new markets. As Eastern European countries opened up to the West, they became a target for coproduction.

Broadcast programming was often controversial, sometimes in entertainment, sometimes in news. “Trash TV” looked like it might be a fad, as 1988’s hottest show, hosted by Morton Downey, Jr., was canceled because ratings and advertising dropped. Dramas dealing with real-life issues frightened advertisers, as always. Roe vs. Wade, NBC’s TV movie docudrama on the famous Supreme Court abortion rights case, was critically praised, but its controversial nature caused several sponsors to withdraw. CBS took a chance with a format that years before had virtually disappeared from prime-time television: a Western. It paid off: Lonesome Dove, a four-part miniseries, received the largest prime-time ratings in two years. Would Westerns now return to TV?

Broadcasting news was at times excellent, at times disappointing. TV did a good job covering the student revolt in Tiananmen Square in Beijing until transmission was shut down by the Chinese authorities. On-the-spot coverage of the San Francisco earthquake was as unexpected as the quake itself; it came principally from the ABC-TV crew on hand to cover the World Series. Broadcasting provided in-depth coverage of the fall of the Berlin Wall. Broadcasting did try to cover the U.S. invasion of Panama, but the military did not allow the press freedom to report the early days of the conflict. Some journalists said that at least they were given more opportunity to cover the story than they’d been afforded at the U.S. invasion of Grenada. Strangely, the electronic press made little outcry about what many considered was a restriction of their First Amendment rights of freedom of the press.

Some news shows tried to fake their stories during 1989. By the end of the year, the television networks were apologizing for having used simulations in news reports. Radio, which once had been a bastion of news reporting, was its old self in 1989 with highly praised coverage of the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska.

Gradual breakthroughs into the male-dominated and -controlled broadcast news field saw a number of women, such as Jane Pauley, Connie Chung, and Diane Sawyer, in key reporting and anchor positions in network and local news.

The networks were willing to pay big for big ratings. Live major competitive sports drew such audiences for broadcasting, cable, and, already beginning to make huge sums of money, pay-per-view TV. In 1989 CBS paid $1 billion for seven years’ rights to the NCAA basketball tournament games. Major league baseball did even better, getting $500 million from radio and television for just one year, 1989.

It was a busy year for the FCC. It hung tough as a regulator when it investigated many and fined some radio stations for violations of its indecency rules. It wasn’t so tough, however, when it granted a number of waivers of its one-to-a-market restriction, at times appearing to dismiss its duopoly rule with impunity, including a waiver to the Boston Celtics basketball team to buy both a TV and a radio station in the Boston market. It voted to repeal the compulsory license whereby cable was authorized to use copyrighted material of the stations it carried by paying one statutory fee. Broadcasters sought such repeal in order to force cable to negotiate for each station or program on an individual basis. Any final change, however, would have to be made by Congress. Also in 1989 the FCC affirmed its new syndex rules, to go into effect in January 1990; it authorized 200 new class C (25-kW) radio stations; and eliminated a 44-year-old rule limiting network-affiliate contracts to two years. Further, unable to reinstate a must-carry rule, the FCC temporarily settled for the requirement that cable companies offer subscribers an A/B switch.

Fig 8.11 National Public Radio has enjoyed steady growth in listenership.

Courtesy NPR.

The FCC and the courts continued to back away from the affirmative action practices of the late 1960s and early 1970s. The U.S. Court of Appeals found unconstitutional the FCC’s “distress sale” policy, under which a station in danger of losing its license, thus forfeiting a chance to sell its station, could sell at a reduced rate to a minority or female applicant. The FCC reduced the impact of challenges by citizen groups through petitions to deny in license renewal proceedings: It banned settlement payments made by stations to petitioning groups in order to get the groups to withdraw in exchange for voluntary changes on the part of the station.

Congress, throughout much of the year, was involved in hearings and bills that reflected a proregulatory attitude. Among its concerns were children’s television, Fairness Doctrine codification, cable reregulation, and violence, sex, and drugs on TV. The only major law to come out of this activity, though, was enacted the following year, 1990, and concerned children’s TV.

Fig 8.12 CDs have replaced LPs as the preferred sound medium at home and in the broadcast studio.

Noncommercial and formal and informal educational television reached a few milestones in 1989. CPB and public television station organizations agreed to a new program-funding plan. Television programming into the schools, something that had been going on for about 40 years, had taken a new twist with Channel 1, a Whittle Communications concept, providing receiving equipment and news programs free to schools. The catch? Commercials to a captive audience, which raised the hackles of some educators but seemed worth it, for the equipment and programming, to others. Other groups, including Turner and Monitor, began to offer programming comparable to Channel 1 but without the commercials. A relatively new phenomenon in communications—public access programming controlled and produced by the public—had come about in 1972 when the FCC required cable systems to offer such access channels; by 1989, there were some 10,000 hours of programs a week being carried over cable public access channels on more than 1,200 cable systems.

Key technical developments in 1989 included the first 100% 3-D television broadcast; the demonstration by Panasonic of a prototype digital video camcorder; the first regularly scheduled HDTV in the world—in Japan, using DBS; and the FCC’s facilitation of satellite television by granting flexible use of frequencies to DBS applicants.