Chapter FOUR

The Furious

War and Recovery—Full of Sound and Fury, Signifying… Transition to TV

The decade of the 1940s began with radios in more than 80% of U.S. households; 50 million-plus sets were in use. Advertising revenues for radio totaled $155 million in 1940. More and more newspapers solved the problem of competition by buying or constructing radio stations; in 1940 newspapers owned a third of the country’s stations. FM continued to move forward, owing to the perseverance of Edwin Armstrong, and an FM broadcasters association was formed to lobby for additional spectrum space. The FCC established rules for FM radio, and by the end of the year dozens of new FM stations had been authorized. FM supporters touted the new sound, as The New York Times wrote, for its “golden tone, less noise, no interference” qualities. A number of stations used microwave interconnections to create FM networks. So impressive was the FM staticless signal that the FCC decided, in 1940, to authorize FM for television’s sound. While this step would be a boon for TV, it would turn out to be a blow to FM. TV, not FM, was given priority as the new medium. The FCC authorized limited commercial TV operation, with the proviso that stations make clear to the public that they were still experimental. RCA, eager to sell its TV receivers to the public, was not about to adhere to the FCC dictum and advertised its sets on its NBC television station. So powerful was RCA that it even got the FCC to support its monochrome (black-and-white), 441-line, 30-frames-per-second system, even though Peter Goldmark, a CBS scientist, had already developed a workable color system using whirling discs.

Other technical advances anticipated the military needs of the upcoming years. Television was tried out in airplanes, and although miniaturization was still far off for TV, small radios were developed using dry batteries that could provide energy for vacuum tubes. Portable transmitters and receivers, including walkie-talkies, later became invaluable combat equipment.

News began to dominate programming, with more and more hours devoted to the war in Europe at the expense of light popular music and talk shows. CBS began to build up a corps of correspondents who would gain national respect and loyalty as the voices of the war: Ed Murrow’s “London After Dark” nightly reports of the blitz; William L. Shirer’s coverage of France’s surrender to Germany at Compiégne; the voices of Howard K. Smith, Robert Trout, Eric Sevareid, and Charles Collingwood came into most American households during the next few years. The remarkable CBS team was orchestrated by CBS’s chairman, William Paley, who told his European correspondent, Murrow, to hire the best reporters he could find, and Murrow did. Public interest in war news carried over into domestic politics, and television, to promote new audiences, for the first time broadcast the election returns as well as the Republican and Democratic National Conventions.

The public still wanted to be entertained, of course, and music would continue to be the most programmed radio format for the next few years—representing about 50% of the networks’ schedules in 1940. But it encountered a roadblock. As a result of a lawsuit, a federal appeals court decided that records purchased by radio stations could be played without prior consent of the record company or the artists. Yet the statutory fee negotiated by ASCAP and NAB still remained, and in 1940 ASCAP raised its rates, believing that music played on radio harmed the sales of records and sheet music. ASCAP refused to renew many stations’ contracts that expired at the end of 1940. Although the fledgling NAB-created BMI tried to take up the slack, ASCAP controlled the most desired music, and by the end of 1941 most stations had re-signed with ASCAP at compromise fees.

1941

The attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, bringing the United States officially into World War II the following day, resulted in severe restrictions on radio and television’s growth—and brought about some of radio’s finest hours.

Beginning at 2:31 Eastern time that Sunday afternoon, December 7, 1941, the networks cut into their regularly scheduled programming to announce the Japanese bombing of the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor. Within hours, radio and even the relatively few television stations were broadcasting hastily assembled features and documentaries on Pearl Harbor, the Pacific area, and Japan. The next day, December 8, the largest radio audience to date—62 million people—heard President Roosevelt’s “day that will live in infamy” declaration of war.

Aware of the value of electronic communications and equipment to the war effort, the U.S. government began a series of restrictions and controls that would continue throughout World War II and even into the postwar period. A number of factors prompted government action. One was the need for electronic parts by the military, resulting in the conversion of facilities that turned out radio and television parts for defense needs. Another was the matter of security. “The enemy is listening,” “Loose lips sink ships,” and similar slogans were taken seriously, and there was fear of spies using radio to convey or receive information that could help the enemy. Amateur stations were shut down to prevent such occurrences.

Fig 4.1 An older de Forest at work on television in the 1940s.

A further goal of government action was to increase effective instant communication with our allies and to use the already proven propaganda power of radio to reach people in enemy countries. Shortwave international transmission was strengthened, including the development of a new “electrically steerable” antenna by NBC engineers. According to The New York Times, the antenna worked by “beaming the wave of a 50,000 watt international transmitter, its effective output is raised to something like 1,200,000 watts, and much greater signal strength results in the country over which the beam is aimed.” In the following year, 1942, the government took over all private shortwave stations that could send a signal to foreign countries and put these stations’ programming under the Office of War Information (OWI). Conversely, the government also set up a service to monitor foreign broadcasts, to intercept propaganda from the other side and any messages that might be used by subversive elements in the United States.

During the early part of 1941, before the United States’ official entry into the war, the FCC took a number of actions affecting broadcasting. The commission’s investigation into network monopoly practices begun in 1938 was completed with the issuance of a Report on Chain Broadcasting. This report was aimed at protecting individual affiliate stations from what the FCC felt was undue control by the networks. Among other things, it limited affiliate contracts to one-year renewable periods, permitted stations to use programs from other networks, prevented networks from interfering with station programming and scheduling prerogatives, and stopped networks from controlling affiliate stations’ advertising rates for other than that network’s programs. The report’s most dramatic determination, however, was that NBC’s ownership of two networks constituted an unacceptable monopoly. Both NBC and CBS were furious and attempted to convince Congress and the American public that the new FCC regulations would destroy broadcasting. They challenged the FCC in the courts. In 1943 the Supreme Court upheld the FCC, and NBC had to divest itself of one of its networks; it kept the Red and sold the Blue, which later became the American Broadcasting Company (ABC). Despite the networks’ protests to the contrary, radio did survive, and years later, after television changed the structure and programming of radio, NBC, CBS, ABC, and the Mutual Broadcasting System (MBS), among others, were granted permission for multiple radio network operations to distribute different program formats. Only two months before issuing the 1941 Report on Chain Broadcasting, the FCC had announced that it was beginning an investigation into the newspaper ownership of stations, a study that would result in action in that area as well some years later. While proposing restrictions on some broadcast practices, the FCC loosened up in one significant area: License terms were extended from one to two years.

In April 1941 the FCC issued the first full commercial TV authorization after adopting the technical standard recommended by the National Television Systems Committee (NTSC) of 525 lines and 30 frames per second. This would turn out to be the poorest-quality television standard in the world, and in the 1990s it was one of the reasons for the pressure to adopt and implement a high-definition television (HDTV) standard to improve picture quality.1 Both CBS and NBC converted from experimental to regular commercial TV broadcasting in July 1941, with about 15 hours of programming a week each.

Fig 4.2 As early as 1941, broadcasters saw the value of mobile television cameras. This DuMont field unit sports two cameras atop a three-quarter-ton truck.

The FCC also gave television new frequencies, replacing the previously used AM frequencies. It put FM on a new band, 42–50 MHz; television had channel space on some higher frequencies. FM and television had been fighting for the same desirable spectrum space, and the FCC’s action prompted some FM advocates to suggest that the government was trying to hamper the growth of FM to protect AM. By the time the United States was in the war, there were some 40 FM stations on the air and about a half million FM receivers in use.

The FCC entered the area of program regulation in 1941 when, in deciding on a challenge brought by the Mayflower Broadcasting Company against the license renewal of a Boston station, it stated that broadcasters would not be permitted to editorialize—that is, a station could not use the airwaves to present the owner’s particular points of view. The Mayflower decision set the stage for later rulings that would become known as the Fairness Doctrine, in which stations were permitted, even encouraged, to present controversial material but were required to present opposing viewpoints as well. Other kinds of programming were encouraged, especially those that aided the war effort. Immediately after Pearl Harbor, networks and stations began to plan and produce patriotic dramas, with characters and plots that were prodemocratic and antifascist.

In New York a young radio performer named Martin Block started a music show on WNEW in which he interspersed comments between records and gave the impression that people were listening to the bands and artists as they were actually performing. As earlier stated, this program, The Make-Believe Ballroom, would have a great influence on the development of radio’s basic format, that of the disc jockey show.

1942

On one front, business as usual for broadcasting ceased in 1942; on another, it didn’t. Radio stations that were on the air stayed on, and in fact, federal excess profits tax laws made it possible for them to keep pace with the rest of the economy and make money during the war. Radio became a necessity for Americans as an important and frequently on-the-spot source of news about the progress of the war. Virtually everyone had a family member or friend in the Armed Forces and avidly listened to daily news reports. In addition, the pressures and fears generated by the war—although U.S. civilians experienced none of the horrors and not even any of the deprivations of war, except for the shortage of some goods and services—and the long, arduous hours many civilians were putting in at war plants resulted in an increasing demand for escapist entertainment. Radio supplied it. In addition, the government understood the propaganda value of radio for boosting patriotism and morale, and radio admirably served that purpose, too.

On the negative side for broadcasting, the electronic and technical components of radio and of the fledgling television medium were needed for the war effort. Consequently, within a few months of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the government put a freeze on the construction of new stations, on the expansion of existing stations, and on the manufacture of radio and television receivers.

The United States’ first year in the war was disastrous. The loss of the Philippines, the surrender and subsequent death march in the Bataan Peninsula, and the debilitating Coral Sea battle helped create depression and fear in the United States. This paranoia resulted in the U.S. government creating detention camps in which it concentrated more than 100,000 Japanese Americans, confiscating their homes, businesses, and personal property. By the end of 1942, however, the United States had begun to seriously challenge the Axis powers, beginning a series of Pacific island conquests with a victory at Midway Island and landing an invasion force in North Africa. These events raised national morale. Radio not only reported the news but was there while it was being made.

How was the United States going to handle its propaganda needs? In most other countries during wartime, the government took over the principal means of public information—newspapers, magazines, radio, and film. Because of newsprint shortages and the fact that there was a fair amount of illiteracy, in all countries radio was the principal day-by-day means of informing, stimulating, and persuading, with movies serving longer-range goals. Was a dictatorial takeover of the communication industries, or even of the radio medium alone, appropriate for a country that said it was fighting for democracy over fascism? The United States decided it was not. A lesser step was either to administer, or at least to oversee, the programming of radio, preparing the scripts and deciding on the productions and scheduling that would best serve the U.S. war effort. That step, too, was judged a bit drastic. The United States finally decided to seek radio’s cooperation through voluntary means, perhaps with a little assistance and persuasion.

ARCH OBOLER

THE LATE ARCH OBOLER WAS ONE OF THE GOLDEN AGE’S PREEMINENT RADIO WRITERS

My plays were written for a very special medium—radio. Radio drama was a wonderful art form. First and foremost, a radio play is a collaboration; a marriage of elements—words, sound effects, music, actors, and the listener.

Fig 4.3 Arch Oboler’s innovative radio plays entertained audiences throughout the turbulent 1940s. Here he directs Lights Out, WENR Chicago, 1935–1939.

Courtesy Havrilla Collection, Broadcast Pioneers Library.

The Office of War Information (OWI) was established in 1942 to handle this task. A highly respected radio news commentator, Elmer Davis, was named head of the OWI. Essentially, OWI prepared daily information bulletins on government aims and needs and sent them to networks and stations with the request that the producers, writers, directors, and performers attempt to incorporate the information and its purposes in their programs. The industry was happy to comply. OWI sometimes prepared scripts and even produced several programs on matters that were considered essential and offered them to the radio industry. For example, because cooking fat was needed for processing into the glycerin required for gunpowder, the government scheduled specific days on which housewives were asked to bring to collection stations the cans of cooking fat they had saved. This information was forwarded to radio producers, who then incorporated it into skits, discussion programs, and even the dialogue of characters on soap operas. As might be expected, more than one comedian felt compelled to remind housewives to “bring your fat cans” down to the collection depots.

Even music and variety programs joined in the patriotic effort. Such war songs as “Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition,” “In Der Führer’s Face,” and “This Is the Army, Mr. Jones” were popular favorites throughout the war, and Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America” became our unofficial second national anthem. Variety shows such as The Army Hour featured comments of fighting personnel, from privates to generals. Dramatic scripts and documentaries written and produced by the United States’ best talents informed and inspired people in such program series as This War and This Is Our Enemy. Perhaps the program best known to troops overseas was Command Performance, a variety show featuring America’s biggest stars. It was broadcast over all shortwave stations in an attempt to counter the anti-American propaganda on the radio programs of Tokyo Rose and Axis Sally, propaganda that affected the morale of many service personnel.

OWI also coordinated the release of all news announcements and decided on priorities for what should or should not be said over the air. For example, recruiting for the Armed Forces and the promotion of War Bond sales were high priorities, and stations were asked to voluntarily censor any information pertaining to troop movements, casualty lists, and rumors, as well as person-in-the-street interviews (lest some subversive element get onto the air something harmful to the war effort). Weather reports were censored, since enemy planes could use information about the weather to their advantage; even announcements of cancellations of athletic events were not attributed to the weather. An Office of Censorship issued a voluntary set of guidelines with which virtually all stations conscientiously complied. The NAB issued a guide to wartime broadcasting, listing in it a number of prohibitions, such as broadcasting information on war production, troop movements, scare headlines, commercials within news reports, sound effects that might be confused with air-raid sirens or other alarms, or any entertainment or commercial material that might be confused with important news bulletins. Though broadcasters took the war effort seriously, many were concerned that some of the censorship by the military was unnecessary and kept legitimate information from the public; one of the newspersons making public objection was Ed Murrow.

Advertising agencies and associations formed the Volunteer Advertising Council and lent their talents to writing and producing literally thousands of programs and spot announcements for the government, promoting everything from the salvage of scrap metal to writing V-Mail (single sheets that folded into their own envelopes and could be photographed in reduced form to save materials and space) to members of the Armed Forces overseas. Advertising blossomed during the war. A tax on excess profits, designed to reduce war profiteering, set a 90% levy on profits over and above what would reasonably be expected in normal times; an exemption was made for any such profits spent on advertising. Radio stations, ad agencies, and advertisers all benefited considerably from what was called “the 10-cent dollar”—that is, the amount it actually cost to get a dollar’s worth of commercials. In 1942 radio set a new record of $255 million in gross billings.

Radio was considered so important that broadcasting was designated an essential industry and the Selective Service System set up deferments for certain radio personnel. Using its chain of shortwave and other stations in various countries of the world, the United States began the Voice of America (VOA), which very successfully produced programs carrying U.S. propaganda not only to enemy but to allied populations. A parallel system of radio stations, Armed Forces Radio (AFR)—which later became the Armed Forces Radio Network (AFRN) and in subsequent years the Armed Forces Radio and Television Network (AFRTN) and the Armed Forces Network (AFN)—was set up to reach U.S. personnel through-out the world. By the end of 1943, AFR operated 306 stations around the globe.

The bad news for the radio industry was that the Defense Communications Board ordered the cessation of the manufacture of all radio and television receivers and a freeze on the construction of new or the expansion of existing stations. Material and labor had to be invested in the war effort. More than 13 million radio sets had been sold in 1941; the total dropped to less than 4.5 million in 1942; and in 1943, with the war becoming more intense, only about 700,000 home sets were sold. The production of phonograph records was rolled back, too, because the shellac needed to make the discs was commandeered for war production. The government, however, did want stations that were on the air to stay, and these got priorities for maintenance and operating materials.

TV virtually ceased. For a while a few stations attempted to provide special programming, such as training for air-raid wardens and sports and variety programs for GIs in stateside hospitals where there were communal TV sets, but there was no economic base on which to continue. A major exception was the DuMont station in New York. It began broadcasting in 1942 and stayed on the air throughout the entire war, hoping to steal a march on the NBC and CBS TV stations, which went dark, and to become a challenging third TV network when the war ended. Ultimately, though, the power and resources of NBC and CBS won out, and a few years after the war the dreams for a DuMont television network ended.

World War II, like World War I, was responsible for the creation of new communication technologies for use by the Armed Forces—technologies that would immeasurably assist the growth of civilian communications once the war ended. For example, miniaturization of equipment for portability on the battlefield was a priority. One of this book’s authors, who served as a combat infantry radio operator in Europe, remembers the relief of being able to exchange the large, heavy Signal Corps Radio (SCR-300) he carried on his back for the handheld walkie-talkie. Another key development was the attempt to facilitate the making, transmitting, and playing of audio recordings. U.S. and German scientists both were experimenting with a form of wire or tape to replace the bulky and breakable records. The United States used the wire recorder in 1943 but learned the following year that Germany had developed and was using the magnetic tape recorder—a much more advanced device that would later revolutionize the radio industry. The radio fac-simile photo made advances, too, with U.S. and Russian engineers able to transmit aerial views of battlefields in less than 20 minutes from Moscow to the United States.

Not every development in broadcasting related to the war, however. The president of the American Federation of Musicians (AFM), James C. Petrillo, felt that the use of recordings on radio decreased the demand for live performances by his musicians. He asked stations to pay fees to AFM, similar to their payments to ASCAP. When they refused, he called a strike, forbidding AFM members to make any more recordings. The strike continued for two years.

1943

The FCC’s monopoly rules and cross-ownership investigation resulted not only in the CBS–NBC lawsuit but in pressures on Congress from both the newspaper and the broadcast industries to stop FCC action. A Georgia congressman, Eugene E. Cox—who had been accused by the FCC of accepting illegal payments for repre-senting a Georgia broadcaster before the FCC—convinced Congress to investigate the FCC. The court’s upholding of the chain broadcasting rules and the forced sale by NBC of its Blue Network further fueled anger against the FCC. Cox chaired the committee that subpoenaed the records and personal finances of all FCC commissioners from 1937 on. Foreshadowing the McCarthy era a decade later, the Cox committee accused the FCC of being unpatriotic, of aiding subversives, of overstepping its authority, and of being corrupt. The results included an exposure of Cox’s motives as well as the validity of some of the charges of corruption; the resignation of the FCC chairman, James L. Fly, the following year, 1944; and the withdrawal of two other commissioners. But the principal consequence from then on was to make the FCC more responsive and accommodating to the political power of Congress.

As the war escalated, so did the role of radio. The U.S. Army Air Corps joined the British Royal Air Force (RAF) in bombing Germany, the Allied invasion of Italy drove back the Axis powers and forced Italy to switch sides, the Germans were about to suffer a significant defeat at Stalingrad, and the U.S. forces in the Pacific were coming closer to Japan. Radio programs reflected the progress of the war, with some already beginning to deal with the requirements for peace and the postwar world. Even music enlisted—one program, entitled Music at War, raised morale by featuring songs of the various branches of the armed services. Situation comedies and comedy/variety shows continued to be the most popular. With an uncharacteristic sensitivity, perhaps prompted by a growing understanding of the philosophy of the enemy, the U.S. government commissioned radio shows to heighten public perceptions of black (then called Negro) troops and of women in the Armed Forces. Such writers as Norman Corwin and William Robson produced series showing the heroism and abilities of blacks and women. Once the war was over, these kinds of programs, providing equal opportunity and countering bigotry, would not again be found to any extent in commercial broadcasting until the civil rights and women’s liberation movements of the 1960s and 1970s, respectively.

Musicians’ power was recognized in 1943 when certain recording and broadcasting companies began to pay fees directly to the AFM union. The strike called by Petrillo lasted another year, however, until the networks capitulated, too. Radio got a bonus from the FCC in 1943 when the commission extended the license periods for AM stations from two to three years.

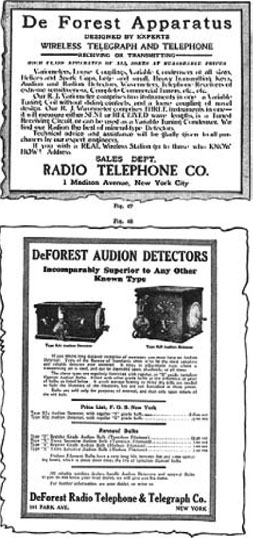

Fig 4.4 Old de Forest radio equipment advertisement as reproduced in a 1943 magazine.

Two important technical developments, one in the laboratory and the other in the courts, occurred in 1943. First, the use of radar was making it possible to detect enemy aircraft at far distances and to fly at night with significant reduction in the risk of collision or crash. Broadcasting magazine called radar the “wartime miracle of radio.” Second, the Supreme Court issued a ruling in a case that stemmed from a controversy over who actually invented radio. Although Marconi had long since been given credit for developing its principles, an American engineer and physicist, Nikola Tesla, claimed that his notes and papers proved that he had in fact preceded Marconi in inventing the principles of radio. The Supreme Court upheld Tesla’s claim—but too late for Tesla. Earlier in the year, bankrupt, depressed, alone, and unrecognized for what he felt was a great contribution to society, Tesla died. Today Tesla Societies are still trying to convince historians, the public, and the broadcast industry of Tesla’s claim to fame as the true inventor of radio.

1944

The public continued to be hungry for news, especially as the tide of war turned in favor of the Allies and its end was almost in sight. D-Day signaled the invasion of Europe, and General Douglas MacArthur returned to the Philippines. The networks’ percentage of program hours devoted to news had increased from about 7% in 1939 to about 20% in 1944. Shortwave transmitters carried battlefield reports from the Pacific, and information and entertainment from the United States to the Soviet Union. On-the-spot D-Day reports were described on wire recorders and as soon as feasible sent to relay stations in London for broadcast directly to the United States.

Fig 4.5 Fred Allen became one of radio’s foremost entertainers in the 1940s. His legendary radio feud with Jack Benny provided many laughs.

Music still dominated the domestic airwaves, accounting for about a third of the network’s schedules; 75% of that was pop music by performers such as Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby, and Glenn Miller. Drama comprised more than a fourth of NBC and CBS programming, with MBS devoting more than a third of its weekly hours to news and talk shows. After the war the volume of news would decrease, and drama, variety, comedy, music, and other entertainment programs would overwhelmingly dominate.

With the war still in progress, politics took on an even greater importance for the public. The largest radio audience up to that time, surpassing the previous records for President Roosevelt’s Pearl Harbor address and for the reports on D-Day, listened to the November 7 election returns of Thomas E. Dewey’s challenge to a Roosevelt bid for a fourth consecutive term; more than 50% of all radio homes in the country tuned in. The year 1944 solidified Clark Hooper’s new ratings system; determined through random telephone calls, it replaced Crossley’s as the principal method of radio audience measurement.

Media barons got a break in 1944. The FCC discontinued its cross-ownership study, and did not at that time go ahead with a ban on newspaper/radio station common ownership in the same community; it decided to rule on a case-by-case basis. The FCC also increased from three to five the number of TV stations a single entity could own. NBC and CBS made their AM programming available to the FM outlets of their AM affiliates at no cost and enticed more advertising by providing these additional outlets to sponsors at no additional charge.

The FCC began hearings in 1944 to determine what to do about frequency allocations for the expected growth of new and existing broadcast services following the war. One key issue was whether to continue the old, low-quality TV standards or to introduce new ones that had been developed during the war. The “old boys,” an RCA-led coalition including NBC, GE, Philco, and DuMont, wanted to protect their already-huge investment by maintaining the old standards; the “new boys,” a coalition led by CBS and including Westinghouse and Zenith, wanted their developing color system and higher definition in the ultra-high-frequency band to be given an opportunity in the marketplace. The old boys won. After extensive hearings, the FCC issued its decision the following year, 1945. The decision strengthened the existing very high-frequency (VHF) TV system, setting six channels in the 44–80 MHz band (the first of which was assigned for military purposes, later to be used for private radio); setting seven between 174 and 216 MHz; and moving FM from its previous 42–50 MHz spot to 88–108MHz. Although this action gave FM considerably more channels—100, of which 20 were reserved for nonprofit educational licensees—Edwin Armstrong was furious. Not only had he lost the much more technically desirable lower frequencies, but the change made obsolete all of the almost 500,000 FM sets in use and all of the existing FM stations’ transmitting equipment. More than one news story in June 1945 told how the FCC furthered television while hindering FM radio.

1945

On V-E Day, May 7, 1945, the war ended in Europe. Then, on August 6, the United States dropped the world’s first atom bomb on Hiroshima, Japan; three days later another was dropped on Nagasaki, and Japan surrendered. Franklin D. Roosevelt did not live to see the end of the war. On April 12 he had died while resting in Warm Springs, Georgia. Radio carried the news of these momentous happenings throughout the world. One of this book’s authors remembers the moment when he, along with other GIs in his company in Europe, heard the news of Roosevelt’s death over AFR. Many of these battle-hardened veterans retreated to private places where they sat silently or cried, most of them having known no other President since their early childhoods, with FDR’s fireside chats having created a closeness that made it seem as though the listener were a member of the President’s own family.

Fig 4.6 Table-model receivers of the 1940s. Today, sets manufactured of Bakelite and Catalin plastic are expensive collector’s items. They are characterized by vibrant colors, which increase their appeal.

Some months later in Germany, as editor of an occupation-force Army newspaper, the same author was able to redo the paper’s format at the last minute because of an AFR midnight announcement of V-J Day, the end of the war in Japan—scooping all other Army newspapers, including Stars and Stripes. As did many other journalists, he quickly learned the power of radio to quickly disseminate news and information.

Other key reporting events in 1945 included the coverage of the charter meeting of the United Nations, with radio carrying the news to virtually every country in the world. What was to become one of the most famous broadcasts in radio history was Edward R. Murrow’s April 15 radio account of the liberation of the German concen-tration camp at Buchenwald: “I pray you to believe what I have said … for most of it I have no words … murder has been done at Buchenwald.” Murrow’s broadcast made a profound impression on the American public. But although Murrow’s sincerity was not doubted, some people were cynical. Why the pretense that this was new, they asked? The United States and the rest of the world had known about the exter-mination camps for years; they simply chose not to do anything about them.

With the war ended, radio writers and producers turned to serious drama as a way of creating their impressions of the lessons of the past and the hopes for the future. In the latter part of 1945, the networks aired a number of classic dramatic programs. Perhaps the most outstanding radio play to capture the feeling as well as the substance of war and peace was Norman Corwin’s On a Note of Triumph, aired on CBS, a production still used as a model for radio students and as a source of understanding for historians.

BRUCE MORROW

“COUSIN BRUCIE,” LEGENDARY POP-ROCK RADIO PERFORMER

I believe I first realized the power of communications, especially broadcast communications, when I was about eight years old. I just finished school for the day and was merrily walking home. When I reached my block (New Yorkese for “street”) I noticed that my mother and several of our neighbors were standing on our porch listening to a little brown box, and they were all weeping. My mom and all of those other strong Brooklyn women belonged in the kitchen preparing the evening repast for their families. What could have kept these loyal domestic stalwarts from their usual chores, I wondered. The little brown box was the table-model Philco radio. This magical cube was telling these ladies that FDR had died and that the nation was in a state of mourning. I realized at that moment that anything so small that could cause such a big emotional reaction had to be magic, and I have always loved magic.

Fig 4.7 Bruce Morrow.

Courtesy Bruce Morrow.

Fig 4.8 Newspaper headline announcing victory in Europe—V-E Day.

The business of broadcasting resumed. As the war was ending, the government reauthorized the manufacture of radio sets. But there wasn’t much time to gear up again, and although only 500,000 radio sets were sold in 1945 (compared with about 13 million in prewar 1940), by the end of the year it was estimated that almost 89% of U.S. homes had radios. Radio advertising grew; one estimate indicates that 35% of all advertising dollars spent in 1945 went to radio. Competition increased, as the NBC Blue Network, which had been divested from NBC two years earlier and sold to Edward J. Noble, became ABC. The growth of news broadcasting and prestige during World War II prompted the development of public affairs programs following the war, and in 1945 Meet the Press, still running in the 2000s, made its debut on NBC.

Television moved more slowly. Of the dozen or so stations on the air when the United States entered the war, a few had already gone back on before the war ended, most of the others resumed as soon as the war was over, and a backlog of 150 applications for TV licenses sat at the FCC. TV sets were quite expensive and there wasn’t that much to see. All stations were local, with regional networks still only in the developing stage. It would be years before television would be hooked up nationally.

The May and June FCC decisions that maintained the NTSC, RCA-backed monochrome standard and gave to television the frequencies previously assigned to FM, thus moving FM to less desirable space, also halted an area of growth that would not begin to reach its potential again for almost a half century. The band that had been used for facsimile experimentation in the 1930s and that by 1939 was used for the first home fax machines marketed by the Crosley Company in Cincinnati was the one given to FM. Although FM devotees were unhappy with the less desirable frequencies, facsimile advocates were devastated because facsimile operations ceased completely.

The euphoria in broadcasting was dampened once again by Petrillo’s AFM. Petrillo ordered AFM musicians not to appear on television, stating that the AFM contract covered neither TV nor the simulcasting of AM and FM music. He wanted his union members to be given the jobs of “platter turners” (or disc jockeys, as they were later called) when a station did not employ a standby live orchestra or band to make up for playing recorded music. For several years AFM battled another union, the National Association of Broadcast Engineers and Technicians (NABET), for control of such studio personnel.

Technical advances helped the business and programming growth of broadcasting. Working to improve on its wire recorder and having discovered Germany’s already developed magnetic tape recorder among captured German matériel in 1944, the United States was able to build its first tape recorder in 1945. RCA offered a significant technical advancement for television that year when it introduced the image-orthicon camera, which would replace the iconoscope camera, providing a higher-quality picture and reducing the need for excessively high levels of light. Although RCA was publicly negative about FM, having stopped its support of Edwin Armstrong and making him persona non grata at NBC, it was secretly developing its own FM system, applying for patents that were presumably technically different from Armstrong’s.

1946

The public interest, convenience, or necessity aspects of broadcasting were brought to the fore by the FCC in 1946 with the issuance of its Public Service Responsibilities of Broadcast Licensees. Called the Blue Book because of its blue cover—and apocryphally because of its emotional effect on broadcast industry executives—it out-lined station program responsibilities in the public interest and established the FCC’s authority to see that stations lived up to those responsibilities. Among other things, the Blue Book set forth four categories of programming considered significant by the FCC: (1) sustaining programs, including those of networks; (2) local live shows; (3) discussions of public issues; and (4) advertising excesses, which the Blue Book sought to eliminate. Broadcasting cried “censorship,” and the NAB claimed that the provisions of the Blue Book were unconstitutional, infringing on stations’ First Amendment rights. The FCC countered that the Blue Book did not “promulgate new rules or regulations, but … codified the Commission’s philosophy to help both licensees and regulators.” Published amid a national euphoria of democratic feeling following the U.S. victory for the “people” over the “dictators” in World War II, the Blue Book received a positive response from government officials and citizen groups who put the interests of the public above those of industry. The Blue Book proved to be the base for continuing actions by the FCC during the next several decades—actions designed to result in programming that served the needs of the public through television and radio alike. The policies emanating from principles set forth in the Blue Book, including development of the Fairness Doctrine for the purpose of enabling all sides of controversial issues to be heard by the public, ceased 35 years later when the deregulatory, marketplace philosophy of the Ronald Reagan Presidency resulted in a reversal of the public interest mandate.

AM radio exploded. A postwar United States was eager for the good life, including entertainment, and radio provided it. The top performers in the country—singers, dramatic actors and actresses, comedy artists, even tap dancers—kept audiences in front of their radio sets night after night. The public was hooked on radio news, and in 1946 a whopping 63% of the people cited radio as their primary source of news. If newspapers were worried then, they had only worse days to look forward to. Radio continued as the principal source of news until television became the favored broadcast medium within a decade, and then the visual medium took over as the primary news source. In fact, by the end of the 1980s the majority of the public said not only that they got most of their news from television but that they trusted television news even more than the news in their daily newspapers.

Both NBC and CBS capitalized on the postwar interest in news. CBS appointed Edward R. Murrow vice president for its news and public affairs operations, and Murrow immediately started a news documentary unit. That unit was first to become famous in radio and eventually to become even more famous in television, especially with the documentaries produced by Fred Friendly and Murrow himself. Students of broadcasting still study Murrow’s Who Killed Michael Farmer? radio documentary and Harvest of Shame television documentary as seminal examples of how documentaries should be made. Even as early as the late 1940s, Ed Murrow began to display the “fire in the belly” that gave his documentaries not only a point of view but the strength and conviction to improve political and social conditions in the country. One new technological asset for news and documentaries was the audio tape recorder, which, in the next few years, would effect a profound change in news and public affairs and indeed in all production and programming.

With automobiles being produced again, the United States became a nation on wheels. Music dominated daytime radio as disc jockeys accompanied travelers along the highways. Announcers offered commentary and news to relieve the frustration and monotony of the increasing numbers of people who commuted to work by automobile. In 1946 the number of AM stations on the air grew from 1,004 to 1,520. By the end of the year, 35 million homes and 6 million automobiles had radios. Despite being set back by the FCC the previous year, FM began a slow regrowth, with 350,000 sets manufactured in 1946. Manufacturers, rashly optimistic, predicted that 20% of all sets manufactured the following year, 1947, would be FM. But it would be a number of years, following a slowdown and recession in FM growth, until that would actually happen. FM continued to be an orphan in the industry, and in 1946 the FM Broadcasters Association, for the previous seven years a part of the NAB, dissolved itself, stating that the NAB was unfairly promoting AM and TV over FM, and formed a new, separate organization.

Ham radio, banned during the war for security reasons, was permitted to operate again, using the full spectrum the amateurs had before the war. Before the end of the next year, 1947, however, the FCC forbade hams to use cryptography, as they had been able to do for many years, and instead required them to communicate in “plain language.”

Dramatic developments took place on the TV front, too. New postwar sets went on sale, and the FCC received 600 applications for TV station licenses. Several television firsts occurred as the new medium attempted to capitalize on the excitement of live visual reporting, among them President Harry Truman’s address to the new Congress as well as the opening of the United Nations Security Council. TV’s growth potential was enhanced as both RCA and CBS began to release a number of their patents for licensing, including those relating to television sets and film equipment as well as radio receivers and transmitters and phonograph records. RCA unveiled a “large” TV—a 15 × 20-inch screen. Moving toward the same network structure as radio, television began to develop station connections. Coaxial cable was demonstrated, prompting The New York Times to state, “It will link nearly all the major cities of the country, and is expected eventually … to become the basis of a system over which television programs from any American city can be relayed to any other.” The FCC authorized AT&T to build a Dallas–Los Angeles link as part of an eventual coast-to-coast cable hookup. NBC, much as it had done in the early days of radio, put together a network of four East Coast cities: New York; Philadelphia; Washington, D.C.; and Schenectady, New York.

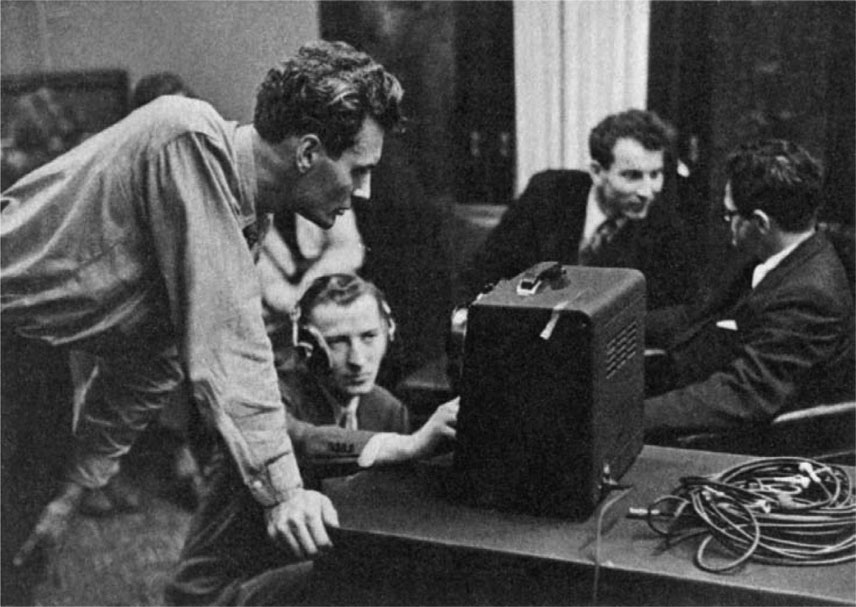

Fig 4.9 The father of the Soviet atom bomb, physicist Peter Kapitza, is interviewed by CBS’s Lee Bland (left) shortly after World War II.

Courtesy Lee Bland.

CBS and NBC vied for the leadership in color television, both demonstrating their latest inventions. CBS’s Peter Goldmark, who invented some of the most significant audio and video processes, developed ultra-high-frequency, high-quality sequential, or mechanical, scanning color TV; his invention was not, however, compatible with existing monochrome sets. RCA’s color system was an all-electronic one and could be seen in black and white on existing black-and-white receivers but was of poorer visual quality. It was the FCC’s responsibility to choose a color system for the country; it took the commission several years of waffling before it finally authorized a usable color TV system.

Fig 4.10 Recording an interview for Norman Corwin’s One World Flight in 1946. Corwin is at the far right.

Courtesy Lee Bland.

The Controversy Over the FCC’s 1946 Blue Book

In September 1945 FCC chairman Paul Porter commented that the radio channels belong to the American people and the people should make known what they want from those who hold a broadcast license. Porter’s call drew a huge response. The war years had provided enormous profits for broadcasters as ad dollars flowed into radio with newsprint in short supply. To sell more time, stations canceled sustained public interest programs in favor of shows that would draw sponsors. Americans began to notice problems inherent with an advertising-supported radio system. In May 1946 the FCC released its Blue Book, which forced broadcasters to defend the commercial broadcasting system. Of all the items the FCC deemed were indicators of radio acting in the public interest, the one that troubled broadcasters the most was commercial excess. They were concerned with the ambiguity of the word excess. But they needn’t have worried. At the bidding of the broadcast lobby, a Republican-controlled Congress pressured the FCC to back off, even having the House Un-American Activities Committee probe the Commission for alleged communist sympathies. Overall, the Blue Book resulted in a new consciousness of responsibility within the industry as major networks responded with some improvement in public interest programming.

LEE BLAND

FORMER NEWS WRITER, PRODUCER, AND DIRECTOR

Today, when recorders literally fit in your pocket, the cumbersome and temperamental wire recorder is hard to imagine. Ed Murrow once told me he booted several of them out the bomb bay door [of his plane] in World War II. But this primitive magnetic recorder was the only “portable” equipment available in early 1946, when Norman Corwin and I took off on his One World Flight. The machine itself weighed over 50 pounds and the spools of wire were about a pound each. It required 120-volt, 60-cycle current, so we carried along a converter, propelled by 12-volt storage batteries as a backstop in many countries with oddball voltages.

Fully charged batteries were almost nonexistent, particularly in places ravaged by war, like Poland. Hence the recorder often fought for its life, and speed changes resulted in Donald, Daffy, and Daisy Duck.

If nursing the machine along (and fighting grease which coated the wire) demanded constant TLC, our biggest problem on returning to New York four months later was yet to come: how to prepare the wire recordings for broadcast. After much consultation with CBS engineers, we decided to transfer every mile of wire—hundreds of hours—to instantaneous discs at Columbia Records. Simultaneously, we fed all of this to Ediphone at CBS, giving us a written transcript of every interview. The Ediphone girls had a huge headache sorting through foreign language translations and Donald Ducks. As the transcripts became available, Mr. Corwin would select blocks of quotes, and I would isolate those passages and put them on discs for him. Off-speed recordings were corrected by Variac—[rheostat] control—and voices were filtered for greatest intelligibility and natural quality. When Mr. Corwin finalized each script in the 13-week series, we then fine-tuned each recorded excerpt in duplicate; the discs were cued in by two engineers simultaneously to protect against failure on the air. The dupes were never needed.

Despite inferior recording quality, Norman Corwin’s One World Flight was an artistic and technical success, thanks to the support of many people in engineering. Incidentally, until Norman Corwin’s One World Flight, CBS had a rigid rule against the use of recordings on the network. But Mr. Paley himself endorsed this project, so the ice was broken, and many other such documentaries followed—utilizing recordings by more advanced equipment, of course.

Fig 4.11 Lee Bland recording a program with composer Sergei Prokofiev in Moscow, June 1946.

Courtesy Lee Bland.

1947

The Cold War mentality that was to destroy reputations and lives and bring the United States to the brink of fascism during the era called McCarthyism began its infiltration in 1947. The fear of Communism, much like the fear of Bolshevism that followed World War I, prompted similar right-wing assaults on constitutional freedoms.

For years the movie moguls had fought the development of unions and had particularly resented writers’ attempts to get a share of the Hollywood pie. With the Cold War as an excuse, several studio heads invited the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) to hold hearings in Hollywood on subversive activities, pointing specifically to a number of leaders of artists’ unions, especially writers. Some studios felt that this way they could bust the unions and regain unchallenged control of all personnel and contractual arrangements. HUAC was eager to get as many headlines as it could, ostensibly in the interests of patriotic protection of its country. What better way than to investigate the most popular people in the country—movie and radio stars? “The Hollywood Ten”—producers, directors, and writers who were to be driven out of the industry or sent to prison—became a household phrase. That the headlines gave some HUAC members national reputations was presumably incidental. Although the “Red under the bed” hysteria started in the film capital, Hollywood, it soon spread to the radio and television capital, New York.

The director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), J. Edgar Hoover, sent a report to the FCC suggesting that there was growing control of the broadcasting industry by Communist elements. The FBI began gathering secret files on anyone whose name it received, even anonymously, as suspect. Conservative radio personalities such as Walter Winchell fanned the flames with implied accusations of disloyalty on the part of those whose beliefs they disagreed with. Three former FBI agents started a newsletter called Counterattack—The Newsletter of Facts on Communism, in which they purported to counter the Red menace in broadcasting by listing the names of performers and others in radio and television who at one time or another might have been praised by, contributed to, or participated in an organization or event that the editors of Counterattack considered un-American. The “Red scare” grew into national paranoia and in the 1950s prompted a full-scale blacklist in film, television, and radio. (See actor John Randolph’s personal account of blacklisting in the next chapter.)

Both AM and FM radio grew in 1947, with some 2 million FM receivers in use by the end of the year. But that was still only about one twentieth the number of AM sets and, although 238 FM stations were on the air and 680 more had construction permits, FM was still far behind the 1,298 AM stations in operation and the 497 additional ones authorized by the end of the year. Radio programming reached its peak with the same kinds of fare we now have on television, including a number of mystery and crime shows. As now, these shows had a full share of violence. In response to public criticism, NBC agreed not to broadcast such programs before 9:30 p.m., and other networks and stations soon followed suit. Self-censorship became a norm in broadcasting, principally to preempt the possibility of even harsher restrictions by the FCC. But later on, when television violence drew high ratings, voluntary restraints on this kind of programming virtually disappeared.

Audiotape came of age in 1947. One of the consistently leading programs on radio in the 1940s was NBC’s Kraft Music Hall, starring Bing Crosby, the most popular singer of the time. Crosby, though, did not like being tied down to the weekly chore of a live show, and the networks refused to permit recorded shows because of the inferior reproduction quality of the discs. Crosby quit after the 1944–1945 season and did not come back until the 1946 season, when ABC agreed to let him prerecord. The technical results were not good. For the 1947 season Crosby experimented with prerecording his shows on tape, which had been refined to reproduce with a fair degree of fidelity. By 1948 the value of audiotape was proved, and within a few years it became standard in the industry—although many programs continued to be done live.

Television was feeling the first surges of maturity, with CBS becoming the first network to contract to broadcast a major league baseball team’s games—in this case, the Brooklyn Dodgers. Later in the year NBC broadcast the first televised World Series—the Dodgers against the New York Yankees, a lucky combination for NBC inasmuch as the largest audience for any of its stations was in the New York area. The first TV show especially designed for children, Howdy Doody, made its debut in 1947; it stayed on the air until 1960. Another children’s show that began on a local station, in Chicago, and was later to move to network fame also started that year: Kookla, Fran, and Ollie. A pioneer anthology drama series, The Kraft Television Theater, began its long run on television.

Both NBC and CBS continued to demonstrate their respective color systems, and CBS petitioned the FCC to designate its system as the accepted one. The FCC said no. Another potential wave of the future for television was large-screen theater presentations, and RCA and Warner Brothers explored that possibility. It was not to come about for some years, and even then it was limited primarily to high-priced sports events, such as world championship boxing bouts. An important technical development was the invention of the zoom lens, or zoomar. Because videotape had not yet been invented, all programs were done live, and dollying in and out for close-ups and long shots was difficult in compact studios with limited space for cameras and with cables almost everywhere on the floor. The zoomar provided much greater artistic flexibility for directors and soon became a standard part of all TV cameras.

Shades of pay-TV! In 1947 Zenith developed what it called Phonevision, a system whereby the TV set is plugged into a telephone to receive scrambled TV signals, which are then decoded for a fee. Although Phonevision wasn’t fully tested for another few years and did not indicate financial feasibility when it was, the increasing number of pay-TV programs in the 1990s suggests that Zenith knew what it was doing—but it was doing it almost a half century too early!

By the end of 1947, 12 television stations were licensed and 55 more had FCC permits to build.

Fig 4.12 Early tape recorders like these revolutionized broadcasting.

Laugh Tracks

The much-maligned laugh track had its origins toward the end of radio’s golden age. In 1947, Army veteran John Mullins, who had recovered embryonic audiotape recording equipment in occupied Germany following WWII, was invited to record an episode of radio’s Bing Crosby Show. The crooner appreciated the idea of airing a show void of flubs, flaws, and weak performances, the bane of live radio broadcasts, so he soon recorded his rehearsals as well as the live audience reactions, which, because they were taped, could overrun scheduled time constraints, and then have the anemic parts edited out. He hired Mullin as his chief engineer; he proved not only to be a skillful tape editor but a potential producer, for when he sensed a performance lagging, he added recorded laughter. Crosby’s producers greeted Mullin’s inspiration with enthusiasm and shortly asked him to save laughter and applause snippets from successful programs that could be inserted when actual audience reaction was lifeless. The idea of a laugh track gained wider acceptance on radio as the medium’s popularity waned and live studio audiences dwindled as well as on early television as more sitcoms and comedy/variety shows were filmed at movie studios that could not accommodate audiences.

1948

The first woman to serve on the FCC, Frieda Hennock, was appointed in 1948. Facing hostility from some colleagues and from most of the industry, she nevertheless was an effective force, standing her ground, sometimes stubbornly, to push for rule making in the public interest. Hennock was at the FCC during one of the most critical periods in its history: a time that included the “freeze” of 1948 through the Sixth Report and Order of 1952, which established the television and radio requirements that shaped the future of broadcasting and that have continued into the 21st century. One of her major contributions was an at times lonely fight to reserve noncommercial television channels for the exclusive use of educational institutions—what we today know as public television.

With the postwar explosion of new technologies, especially television, the FCC was faced with immediate problems of a shortage of TV frequencies, particularly in larger markets, where available TV channels were virtually all gone. Among other things, the FCC had to decide whether to allocate the most desirable audio frequencies to FM or to TV; it had to deal with potential TV interference that rivaled that of radio more than two decades earlier; it faced increasing demands for educational TV channels; and it had to determine which TV color system to choose for the country. There had been only 13 channels, all in the VHF band, available for domestic civilian use, and earlier in the year the FCC had taken Channel 1 away from such use and assigned it to nongovernment fixed and mobile services. The FCC’s chairman, Wayne Coy, suggested that the commission look for additional frequency space for television use in the ultra-high-frequency (UHF) band. The FCC’s earlier rulings on geographic distances between stations had resulted in insufficient mileage separation and, thus, in interference on co-channel stations. In addition, the demand for TV sets outstripped the supply, with major manufacturers, such as RCA, GE, and DuMont, trying to fill a half year’s back orders. On September 29, 1948, the FCC put a six-month freeze on processing any new applications for TV stations. The six months stretched into more than three and a half years before the Sixth Report and Order finally resolved the issues (see coverage of the year 1952 in the next chapter). In 1947 the FCC also extended FM license periods to three years, banned censorship of political broadcasts by stations, and made it possible for many small and poor colleges to go into radio broadcasting by authorizing 10-watt stations. The 10-watters were later abolished at the beginning of reregulation introduced during President Jimmy Carter’s administration.

Fig 4.13 A 1948 advertisement for a “build your own TV” kit.

TV stations that already had construction permits were allowed to build and go on the air during the years of the freeze—with more than 100 in operation nationwide by the time the freeze ended in 1952—but the freeze held back the rapid growth that was anticipated and gave radio a breather as the principal broadcasting medium. Although many top radio performers were lured to television, others remained in radio. But alternate forms of radio programming were already beginning to draw the biggest ratings as the traditional variety, comic, and drama shows made their transition to the visual medium. The quiz show—or, as it’s now called, the audi-ence participation or game show—became one of radio’s most successful formats, with programs like Stop the Music and Hit the Jackpot among the favorites. Through a tax shelter plan, CBS gained an advantage over its rival networks. Working with MCA, the agency representing many of the country’s star performers, CBS was able to lure Jack Benny, Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy, Amos and Andy, Red Skelton, Burns and Allen, and other stars from NBC by setting up their programs under capital gains properties taxes rather than under earned income higher tax rates. In not too many more years these shows would leave radio and move to television—CBS televi-sion, of course. The 1948 talent raids continued into the following year. So successful was CBS’s head, William S. Paley, in luring away top talent that Fred Allen announced on one of his 1949 NBC shows, “I’ll be back next week, same time, same network. No other comedian can make that claim.”

MARTIN HALPERIN

FORMER ARMED FORCES RADIO SERVICE AND ENGINEERING PIONEER

I’ve been a sound recording engineer/mixer for over 45 years. Radio has always been my big love. From a very early age I wanted to be a part of that industry. Like many young people, I “worked” at the local radio station in my hometown while in high school—of course for no pay but just to be a part of it. Later I was a page at NBC in Hollywood while still in high school.

I met many people from the Armed Forces Radio Service while at the network. When I was drafted into the army I tried to get to AFRS after my basic training and was fortunate to do so. I spent 10 years there (part military and part civilian) as a recording engineer. At age 18 I was part of the military/civilian team that installed the first AFRS recording room in their building on Santa Monica Boulevard. We did not get our first tape machine (an Ampex 200) until about 1948, yet all the commercial programs sent overseas had to be edited. From the day the program was first aired in the United States until we sent a de-commercialized copy overseas, it took approximately six weeks. All commercials and reference to dates (the latter because of the time lapse for delivery) had to be deleted. How was that done without tape? Two 160-transcription disc copies were made for each program. A producer would listen to the program, note the time where a commercial, date, etc., took place, and enter it on a log or cue sheet for the recording engineer. In playing back the discs, we would let one of the disc copies run up to the start of the item to be deleted and then segue to the second disc copy, which had been cued to start just past the end of the deleted section. If needed, music, applause, or laughter could be mixed in from a third turntable to make the segue seem natural. With these spots deleted, the programs were shorter than the original program, so I and E [information and education] spots were added as well as music to fill them out. This is a rather oversimplified description of the process. With the advent of tape splicing, this function became less of a chore. I should mention too that when we were first introduced to the tape recorder, we were more impressed by the fact that we could cut the tape to edit than we were by the audio quality. Prior to tape, when we made a mistake we had to start the recording over from the beginning.

Fig 4.14 Martin Halperin in the first Armed Forces Radio Service recording room, circa 1947, showing a 16-inch acetate disk to the announcer Del Sharbutt.

Courtesy Martin Halperin.

Fig 4.15 An early television test pattern.

Courtesy David Sarnoff Library.

The TV stations on the air continued to draw larger and larger audiences, with concomitantly more advertising revenue and in turn more stars to draw even larger audiences and more advertising. The Texaco Star Theater, a comedy/variety show, was number one on television. Its star, Milton Berle, is credited with having been responsible for selling more TV sets than any other factor did in those early days, and with establishing the audience that made television successful. The nation stopped what-ever it was doing to watch “Uncle Miltie” on Tuesday nights—just as it had done for years with the Amos ’n’ Andy radio show. The comedian Danny Thomas, as a guest on one of Berle’s shows, said, “Milton, you’re responsible for the sale of more television sets in this country than any other person. I sold my set, my uncle sold his set….”

A program that was to be a leader in the ratings for two decades made its debut in 1948. Toast of the Town featured as host a taciturn gossip columnist who, some critics said, was totally lacking in stage presence—Ed Sullivan. Sullivan was responsible for introducing many future performing stars on his vaudeville-type program. Subsequently called The Ed Sullivan Show, it featured in several episodes a swivel-hipped guitarist/singer from Tennessee named Elvis Presley, whose reputation required the cameras to stay focused above his waist during his entire TV debut (Presley appeared three times in the 1950s), and in another two appearances in 1964, four long-haired musicians from Liverpool, the Beatles. Another long-lasting program that made its first TV appearance in 1948 was Ted Mack’s Original Amateur Hour, which for years on radio had been the top-rated Major Bowes Original Amateur Hour. One type of program popular then but rarely seen today, except on public television, was serious music. In 1948 the NBC Symphony program series was 10th on the TV ratings charts.

Politicians saw the value of television, just as they had with radio two decades earlier. Both the Republican and Democratic Parties held their national conventions in Philadelphia in 1948. Why? Because Philadelphia was on the coaxial cable linking New York to Washington, D.C., and was also connected by microwave relay to Baltimore. This constituted the largest network audience then available. Both candidates—the incumbent President, Harry S. Truman, and the Republican challenger, Thomas E. Dewey—made use of television. In fact, Truman deemphasized what had become a traditional reliance on newspapers and radio and instead combined a whistle-stop, stump-speech tour of the country with television appearances to win the election. Truman’s inauguration on January 20, 1949, was the first to be televised. The four television networks—CBS, NBC, ABC, and DuMont—pooled their resources, as did the radio networks—NBC, CBS, ABC, and Mutual—to carry the ceremonies. Not only did tens of thousands of people buy sets for this event, but television receivers were installed for the first time in many schools so that students could see and discuss this milestone. The New York Times reported that more people saw this inauguration on television than had seen in person all the previous inaugurations put together. The network idea took hold, and regional networks were established, linking key cities in different areas of the country—for example, Cleveland, Chicago, Milwaukee, Detroit, St. Louis, and Buffalo as a Midwest network.

DANIEL SCHOR

REPORTER/COMMENTATOR, NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO

My first radio broadcast taught me my most important lesson about broadcasting. As newly appointed ABC stringer in the Netherlands in May 1948, I was booked for a live report on the morning news roundup. The story was big—the Congress of Europe, which brought together people like Churchill and Adenauer. Standing by in a little studio (with a squawky shortwave circuit) in Amsterdam, I was told by an ABC editor to listen to the ongoing program and to start my report when I heard myself introduced. Three times the editor warned me not to go one second over two minutes. When I had done my thing, I waited for comment, heard none, said several times ‘Hello, New York?’ until an editor now busy with other things came back. “How was it?” I asked, rather anxiously. “Oh, fine,” he said. “You got off in time.”

Fig 4.16 Daniel Schorr.

Courtesy Daniel Schorr.

The two major networks, NBC and CBS, competed even beyond broadcasting—through their phonograph partners. RCA brought out a 45-rpm record and Columbia Records made a 33⅓-rpm long-playing (LP) record available for home use, leading to increased competition to persuade deejays, by then key elements in radio, to promote their products. Other inventions included demonstration of the transistor by Bell Laboratories and the kinescope method of recording pictures off the TV tube.

Edwin Armstrong was fed up. Not only had the FCC denied him the channels he felt were necessary for optimum FM growth, but RCA was using what he believed were his FM patents in television audio and in FM radio without paying him royalties. Zenith, GE, and Westinghouse had all acknowledged the use of Armstrong’s work and were paying him royalties. But not RCA; it wanted him to accept a one-time cash fee. Armstrong sued.

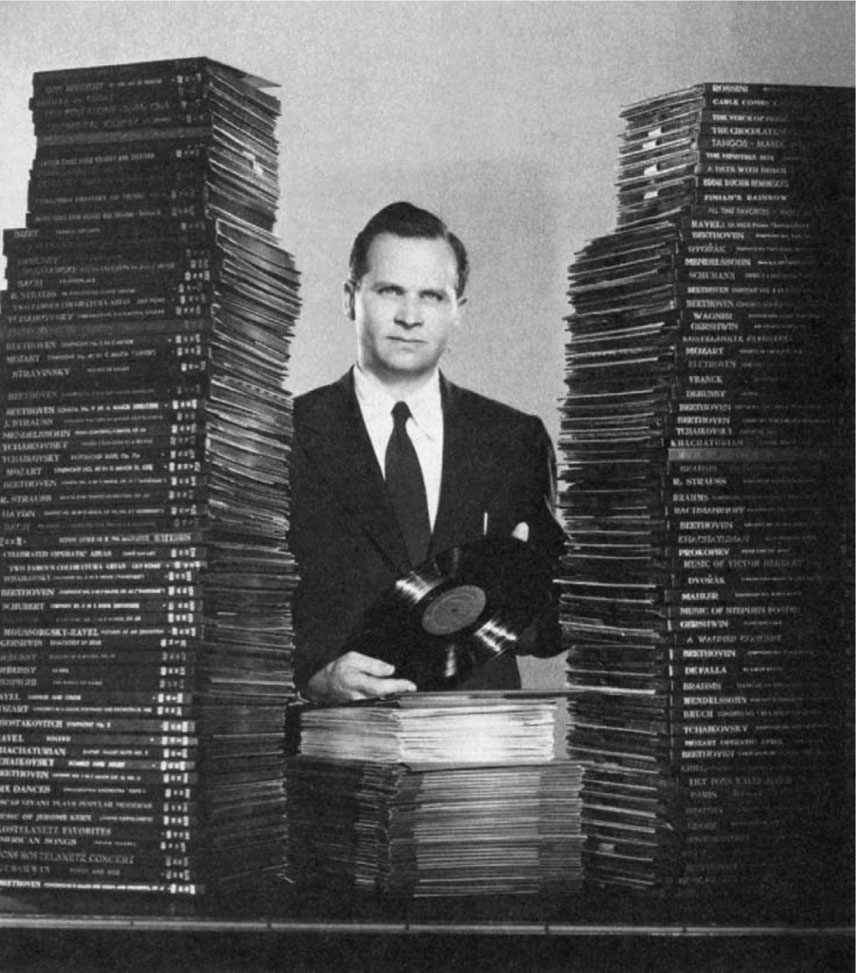

Fig 4.17 Long-playing records, or LPs, not only provided better sound and more of it, they also required less room to store. Here inventor Peter Goldmark stands between stacks of old-fashioned 78s, holding his 33⅓ revolutionary disk.

Courtesy CBS.

Meanwhile, Counterattack published the names of 192 organizations it claimed were Communist fronts, and it began to list the names of performers and others in broadcasting who it claimed were members of these organizations. In fact, only 73 of the organizations were on the attorney general’s list of suspect groups, and most of those named were later removed. But the mud stuck.

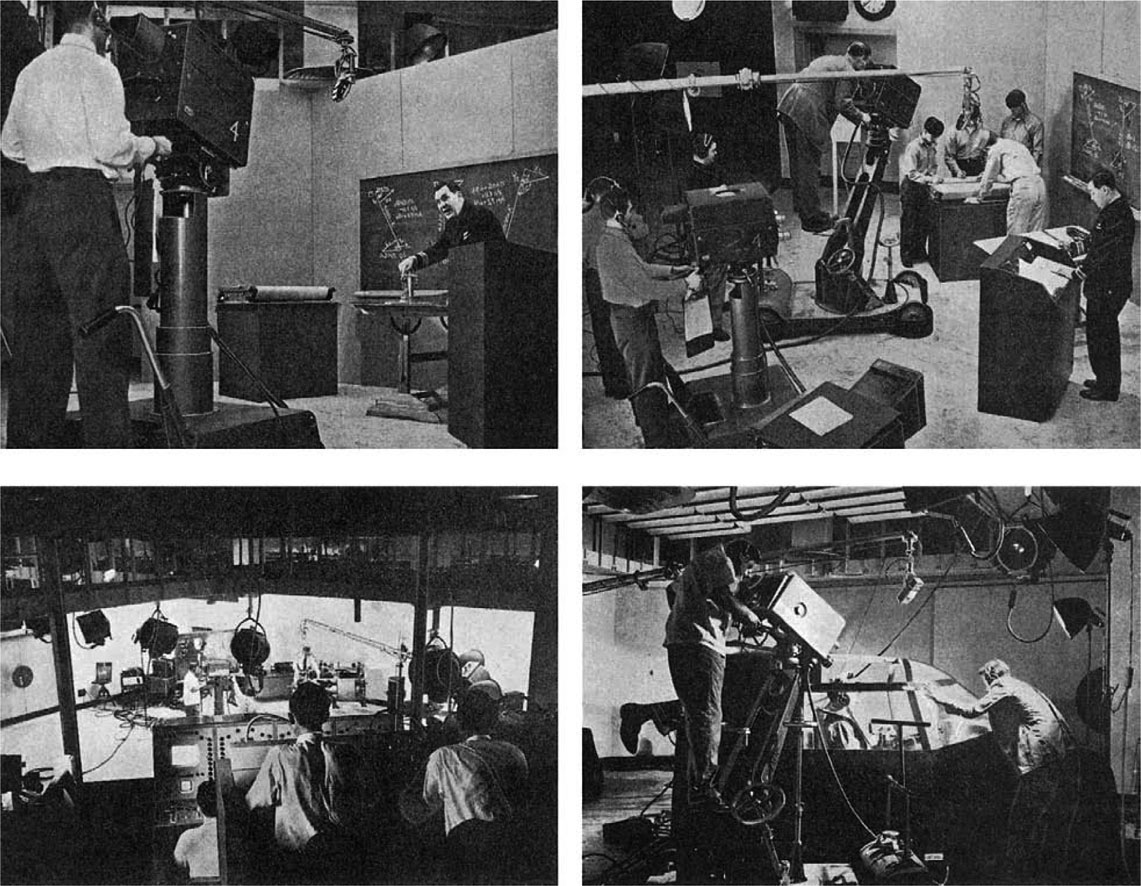

Fig 4.18 Late 1940s television production.

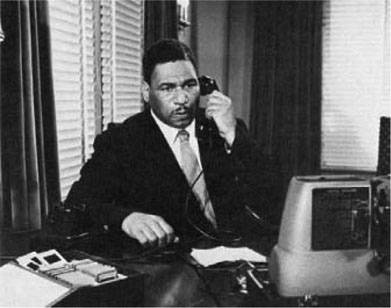

FREDERICK O’NEAL

THE LATE FREDERICK O’NEAL WAS PRESIDENT, COO RDINATING COUNCIL FOR NEGRO PERFORMERS, ASSOCIATED ACTO RS AND ARTISTS OF AMERICA, AND ACTO RS EQUITY ASSOCIATION

During the late 1940s, we organized the Coordinating Council for Negro Performers. Our main purpose as performers was to secure employment of blacks in radio and television, as well as other forms of entertainment. More important, we wanted to change the impression of the viewing public to a more realistic image of blacks and others on the American scene. It was our feeling that television and radio were the greatest media of education and information in the world today. We approached the NAACP through the New York branch to discuss and act on this problem at their forthcoming convention in Atlantic City. Such activism on the part of that organization as well as others has been somewhat successful; we realize there is still much to be done.

Fig 4.19 Frederick O’Neal.

Courtesy Frederick O’Neal.

1949

A key FCC action that was to affect all programming in the future was its 1949 reversal of the Mayflower decision, in which it had forbidden stations to editorialize. Now stations could editorialize but were required to offer time for presentation of the other side of an issue. Coupled with court decisions and other FCC actions in the next few years and using the Blue Book as a cornerstone, the reversal of the Mayflower decision led to the development of the Fairness Doctrine. Under the Fairness Doctrine, stations were encouraged to present issues of controversy in their communities, and if they did so they could be later required to present all sides of a given issue. The Fairness Doctrine, attacked by many broadcasters as a restriction of their First Amendment rights and supported by many citizen groups as an extension of the general public’s First Amendment rights, was in itself highly controversial, right up to the time of its abolition under the Reagan administration’s 1980s deregu-latory policy.

Home Ownership of Radio Receivers, 1922–1950

| YEAR | SETS PER HOUSEHOLD |

| 1922 | 0.02 |

| 1925 | 0.20 |

| 1930 | 0.40 |

| 1935 | 1.00 |

| 1940 | 1.50 |

| 1945* | 1.50 |

| 1950 | 2.10 |

* Lack of increase owing to freeze on set manufacturing during World War II.

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census.

The FCC continued to hold hearings and see color TV demonstrations—and continued to postpone its decision.

Although the hours of TV broadcasting were limited because of the scarcity of suitable material and because the advertising jackpot that was to permit the creation of such material had not yet arrived, TV’s impact on radio nevertheless continued. Radio began to consider less expensive programming and to put on more quiz shows and music. Audience participation “giveaway” shows were popular—13 on ABC, 8 on CBS, and 7 on NBC. The FCC took a dim view of such programs and threatened nonrenewal of licenses for stations that carried them. It would be another decade before the real import of potential abuse was revealed in the quiz-show scandals that shook the entire broadcasting industry in the 1950s.

In addition, the fledgling networks were expanding. In January 1949, AT&T completed the cable connection of 14 cities in the East and Midwest.

Another highly successful radio show made its debut on television in 1949: The Lone Ranger rode right from radio into the video medium. And a new type of television program began with a 16-hour, $1.1 million cancer research fundraiser for the Damon Runyon Memorial Fund. Hosted by Milton Berle, Walter Winchell, Dean Martin, and Jerry Lewis, this was the first telethon.

The Academy of Television Arts and Sciences was created in 1949 for the purpose of honoring television shows and performers, similar to what the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences was doing with its annual Oscar awards. The television award was named Emmy after the image-orthicon camera tube, and in that first year it was presented for Los Angeles programs only. Early television fame was fleeting, however, for many artists. How many people have heard, much less remember, the name Shirley Dinsdale, the person voted the Outstanding Television Personality of 1949?

What did the Fairness Doctrine require?

The issue of reinstating the Fairness Doctrine surfaced when the Democrats took control of both the executive and legislative branches of federal government following the 2008 elections. Right-wing politicians and commentators, in response to offhand comments made by some Democratic legislators, fueled the subject. Early in his administration President Barack Obama’s spokesperson stated that holding to his campaign promise, he was opposed to reinstatement, as did his nominee for FCC chairman. Conservatives, especially the vitriolic right-wing radio talkers that flood the AM dial, charged that the doctrine was an attempt to require broadcasters to give equal airtime for liberal counterpoints. But would it? Exactly what was this Fairness Doctrine? For one thing it never required equal airtime, something initially addressed in the 1927 Radio Act and intended to provide equal opportunity for qualified candidates for any public office. Equal airtime and the Fairness Doctrine are a commingled ruse invented by those who fill the airwaves with one-sided diatribes. The Fairness Doctrine primarily sought the reasonable opportunity for an airing of competing views on matters of public importance and was intended to encourage an open and robust debate. In practice, opposing viewpoints generally received about one sixth of the time given to the original perspective.

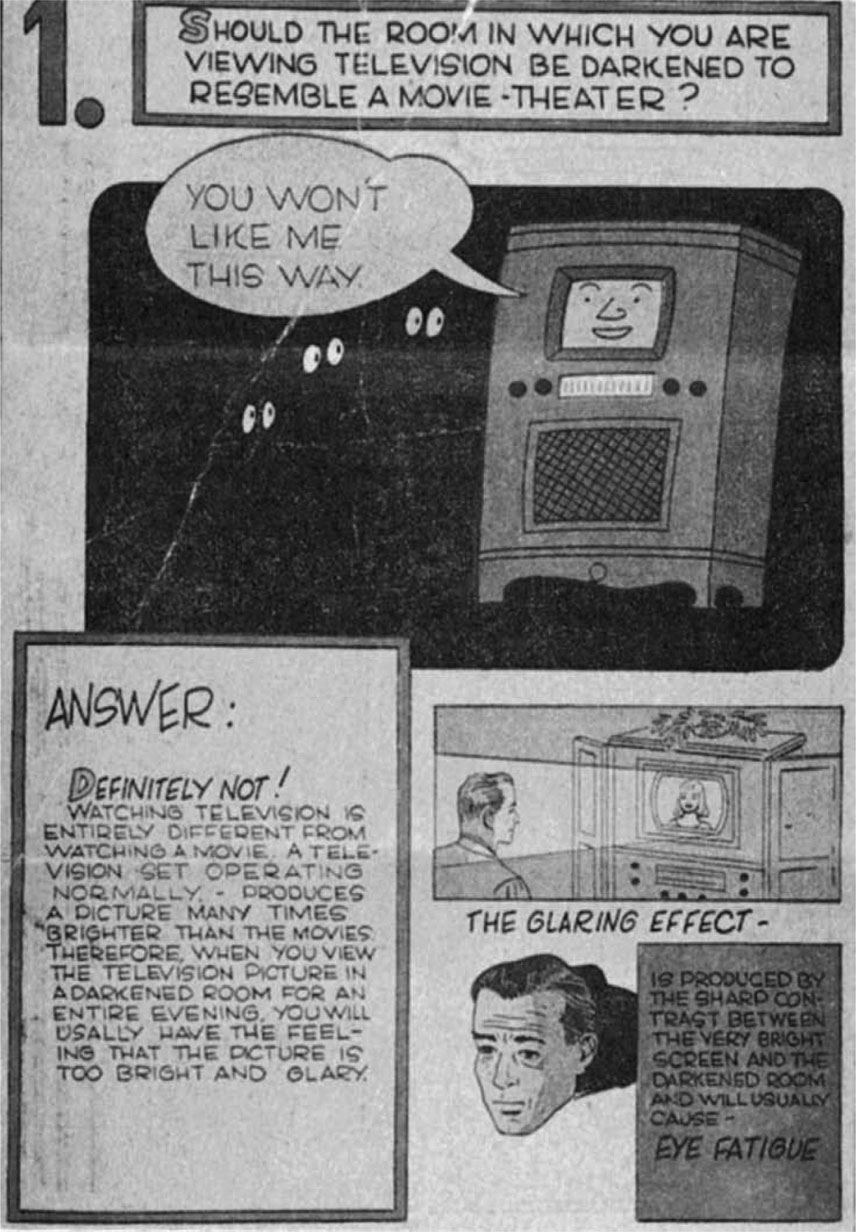

Fig 4.20 A booklet entitled How to Watch TV advised viewers how to avoid eye fatigue.

Courtesy Smithsonian Institution.

1 The Smithsonian’s Elliot Sivowitch reminds us today that in 1941 this standard was pretty good, considering that the British, who had the most active service, were using 405 lines. Sivowitch adds that engineers are not unanimous in their support and enthusiasm for HDTV. “It is not entirely what it purports to be,” says Sivowitch.