Chapter TEN

The New Century: The 2000s

Webs and Digits

The first decade of the new century was not only a new millennium for the world but a time of cataclysms and changes in the United States that not only affected the country’s social, political, and economic fabric but revolutionized the status and future of all communications, including broadcasting.

New technologies altered the structure, delivery, operations, production, programming, content, and reception of radio and television as we had known them. The traditional radio and television receivers, although having become increasingly portable, saw increasing competition from BlackBerry, iPod, videophones, cell phones, and smartphones, among other devices able to receive audio and video signals or digital signals via the Internet. Increased streaming of programming onto the Internet and, more significantly, the preparation of programming specifically for online distribution, including “Webisodes,” challenged the very nature of the broadcast station system. Video on demand (VOD), video compression, retriever software, digital and high-definition reception, and high-quality mobile technology for receiving audio and video were among the developments that created an entirely new playing field for broadcasting and other media by the end of the decade. A key term describing key change is convergence, the old media making connections with the new media, not only generically but with specific aspects such as YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter. Although the final changeover from analog to digital television transmission didn’t occur until June 2009, early in the decade broadcasters were planning to replace the old signals and, while maintaining their analog signals, many stations began broadcasting in digital as well.

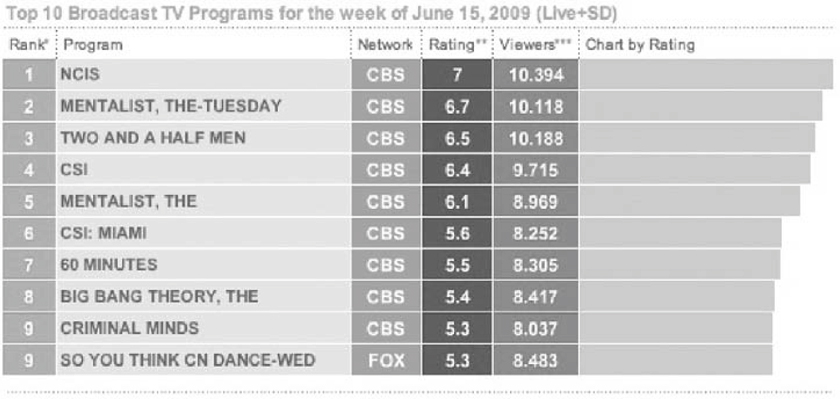

Television programming continued its steady emphasis on reality shows, with a proliferation of such fare increasingly dominating the ratings. By the end of the decade programs such as American Idol (a throwback to the 1930s radio and 1950s TV amateur hours) and Dancing With the Stars topped the Nielsen charts. The success of some of the earlier reality shows such as Survivor and Who Wants to Marry a Millionaire spawned virtually every type of survival, deception, victimization, exploitation, and personal embarrassment program one could imagine. Not only did the ratings prompt the spate of reality shows; by and large, they were considerably cheaper to produce than sitcoms and dramas. Some of the “crime and violence” dramas, such as Law and Order and its clones, CSI and NCIS, became staples, and a few high-quality shows such as The West Wing and Boston Legal reached peaks of critical acclaim and then went off the air. A few medical shows, in particular ER and Gray’s Anatomy, were highly successful, and a tongue-in-cheek satire on suburbia, Desperate Housewives, became a hit. Sitcoms such as Everybody Loves Raymond, The King of Queens, Will and Grace, and an HBO offering, Sex and the City, had substantial runs, with the latter part of the decade seeing more sitcoms with serious comment or satire, such as The Office and Two-and-a-Half Men. Seinfeld ended its long run in 1998 and was voted the number-one sitcom of all time in a TV Guide poll. Would an older demographic, remembering I Love Lucy, All in the Family, and M*A*S*H, have agreed?

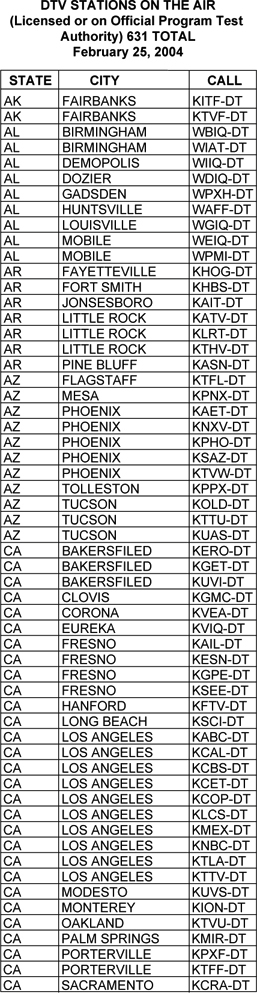

Fig 10.1 First page of lengthy directory listing DTV stations in early 2004.

To many critics, and apparently to many viewers, broadcast fare became more vacuous than stimulating, and more and more viewers turned to the Internet and videos at home for visual fare, with TV networks’ and stations’ audience numbers consistently dropping. Cable-originated dramas began to outstrip broadcast-originated dramas in prestige and awards, most notably premium channel productions such as The Sopranos and Band of Brothers. During the decade cable-viewing numbers surpassed broadcast-viewing numbers. “Infotainment” continued to replace information on news programs, including some of the more prestigious newsmagazines such as 60 Minutes, Dateline NBC, and 20/20. The ultimate in bottom-line programming—that is, broadcast stations and cable channels devoted entirely to commercial selling—became staples, with revenues of some, such as the QVC shopping network, challenging those of major broadcast networks.

Viewer demographics raised questions about whether younger audiences, especially those of college age, were watching programs with any political or social depth or were content with the “chewing gum for the eyes” of innocuous sitcoms and cartoons. Older demographics, for example, heavily made up audiences for Boston Legal and The West Wing, whereas younger demographics were attracted to shows such as South Park and The Simpsons. Inasmuch as the latter shows frequently dealt with similar issues as did the former, does the context and manner of presentation invalidate their impact on the intellectual and emotional growth of their principal viewers?

Program content grew as a divisive issue, especially in relation to perceived indecency. Most of you reading this book remember the infamous “costume malfunction” of Janet Jackson during the 2004 Super Bowl halftime show. It became the hallmark—as innocuous as it was—for congressional complaints and FCC actions. First Amendment supporters were critical of the FCC’s crackdown on alleged indecent or profane instances, while many civic and religious groups called for stricter oversight. Fines for violations were increased tenfold. (See the 2007 book, Dirty Discourse: Sex and Indecency in American Broadcasting.) Although relatively few complaints reached the FCC about alleged indecency in the context of a sitcom or drama or animated show (for example, South Park), concern with the content of shock-jock talk shows increased. An infamous example was Infinity Radio’s Opie and Anthony program’s detailed description of two people having heterosexual sex in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York. Another was rock star Bono’s fleeting use of the “F” bomb, at first dismissed by the FCC but then, under pressures emanating from the Janet Jackson incident, reversed and found profane. The FCC’s increasing conservatism during the decade reflected the conservatism in government, with expectations of change as a majority Democratic FCC, representing a Democratic White House, replaced a majority Republican FCC in 2009.

Video games grew as sources of video entertainment, with both positive and negative criticism. Some became more violent and bigoted, with the intended victims and “bad guys” represented by specifically designated religious, racial, ethnic, gender, and other groups. Conversely, later in the decade, a few of the new genre of video games were oriented toward social awareness, such as the player acting the role of an immigrant falling afoul of the US. immigration system or of a person in a refugee camp in Darfur or Gaza.

In many ways the media both affected and reflected America’s social, political, and economic upheavals and transformations. Defining the decade and the benchmark for almost all other events was the September 11, 2001, terrorist bombing of the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. “9/11” was the seminal act of foreign terrorism on U.S. soil; domestic terrorists, members of one of the many armed militia hate groups in the United States, had destroyed an Oklahoma City federal building with a large loss of life the previous decade.

The aftermath of 9/11, especially U.S. government actions in fighting terrorism, attacking the Taliban in Afghanistan, and preemptive incursions in Iraq, created both opportunities and dilemmas for the media. The White House and Congress quickly approved antiterrorist legislation, the USA PATRIOT Act. Inimical to traditional U.S. civil liberties, the PATRIOT Act permitted arrest, search, and seizure without warrant; indefinite incommunicado detention without legal representation or informing the missing persons’ families what happened to them; and secret courts martial and possible executions. The media cooperated with the government in conducting secret wiretaps and spying on millions of Americans’ private e-mails. Racial profiling resulted in arbitrary arrests of people believed to be Arabic or Muslim, and self-styled vigilantes beat and even murdered many. High government officials approved the torture of prisoners, shocking the world, damaging the United States’ moral and ethical reputation internationally, and spurring the growth of anti-American terrorists and suicide bombers globally. Given the media’s usual support of their government in a time of fear or an international conflict, the U.S. media, by and large, ignored, covered up, or downplayed the activities noted here. Should the media have been more critical?

In 2003 the United States invaded Iraq on the basis of President Bush’s and other high government officials’ assurances that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction and was a threat to the United States, and with the implication that Iraq was somehow complicit in the 9/11 attacks. Should the media have made a stronger effort to report to the public that both the U.S. and the U.N. chief weapons inspectors reported to the White House that they found no evidence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, that Iraq had no relationship to the 9/11 attacks or to its presumed perpetrators, Al Qaeda, and that the CIA reported to the White House weeks before the invasion of Iraq that there was “little or no credible probability” that Iraq would attack the United States? The media ignored or underreported the many protest marches prior to and after the invasion of Iraq by hundreds of thousands of Americans in Washington, D.C., millions through the rest of the country, and multimillions throughout the world. Should the media have informed the public more fully of these protests, similar to the protests that forced an end to the U.S. role in the Vietnam War? These are questions scholars and historians will be probing for decades as a way to better understand the ethical and moral role and responsibility of electronic media.

Fixed on 9/11 and its aftermath, the media only cursorily reported continuing quasi-genocidal actions in a number of areas throughout the world, from Sudan to the Congo to Brazil to Somalia to Palestine, hewing closely to the U.S. government’s policies and interests in those areas. In part, media news outreach was hampered by growing economic cutbacks that forced downsizing of staffs at home and in foreign bureaus. Hard in-depth news increasingly took a back seat to features, personalities, and scandals.

The 2000 decade was also a time of greed and fraud, from corporate CEOs looting their companies at the beginning of the decade to the revelation of multibilliondollar Ponzi scams at the end. Early in the decade the media reported corporate executive pilfering of the funds of some of the United States’ leading companies, including media giant WorldCom, absconding with billions of dollars and bankrupting their companies, resulting in the loss of pension funds, jobs, and investments for hundreds of thousands and in turn affecting the economic status of millions. The media reported unsuccessful attempts to obtain documents on secret meetings between high Bush administration officials and some of the corporate looters prior to the revelation of the scandals.

Later in the decade, corporate greed, coupled with incompetence and malfeasance, principally by executives of banking, insurance, and investment companies, created the United States’—and the world’s—worst economic disaster since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Unemployment surged, millions of homes were foreclosed, and countless businesses went bankrupt. Key services to communities, including safety, health, and education, were hard hit, while most of the corporate executives responsible for the economic collapse either retired wealthy or continued in their jobs with huge salaries, benefits, and bonuses. Some segments of U.S. society made out considerably better than others, both at the beginning and the end of the decade. Early in the decade 80% of a massive tax reduction went to America’s 10% wealthiest people. Near the end of the decade, hundreds of billions in taxpayer money designed to counter the economic recession went primarily to bail out the bankers and other corporate entities and their executives while millions of ordinary citizens lost their jobs and their homes.

The recurring calamities in the United States’ largely unregulated economic system affected broadcasting and other media, too. While consolidation in the media earlier in the decade continued to reduce jobs in the field and eliminate local service and variety in programming, ongoing conglomeration permitted by—and to an extent encouraged by—the Federal Communications Commission, coupled with the economic recession, not only increased job losses later in the decade, it affected programming as well as service in the public interest. Even as the number of audio and visual sources—broadcast, cable, satellite, Internet, and other channels—increased, the consolidation of ownership and the economy resulted in less alternative programming and less diversity of information and ideas. Consolidation extended beyond broadcasting, with the Telecommunications Act of 1996 having opened up the playing field to many more teams; for example, Comcast bought AT&T broadband to become the largest cable multiple system operator (MSO). (Carla Johnston’s 2000 book, Screened Out: How the Media Control Us and What We Can Do About It, reveals the extent and effects of media mega-monopolies. The 2005 book, The Quieted Voice: The Rise and Demise of Localism in American Broadcasting, analyzes how consolidation reduces community service.)

The Internet slowly but inexorably began to complement and then to supplant television and radio (whether distributed through broadcasting, cable, or satellite). Thousands of radio stations began streaming their programs onto the Internet. Digital radio signals reached into homes and automobiles. Radio continued to grow—although by the end of the decade it, too, became a victim of the economy—and was chronicled in Sounds in the Dark: All-Night Radio in American Life and Talking Radio: An Oral History of Radio in the Television Age.

The increasing control of media by only a few companies also resulted in compliant news media later in the decade, unwilling to challenge legislation designed to prevent a reinstatement of the Fairness Doctrine (see the “1980s” chapter), the only legal provision for providing access for the presentation of alternate or minority viewpoints on radio and television broadcast stations.

Media news operations were frequently criticized as well for their lack of critical coverage—investigative journalism in the Watergate tradition—of two controversial Presidential elections. In 2000 the election hinged on Florida’s electoral votes; exit polls showed that the democratic candidate, Al Gore, had won, validating his lead in the national popular vote. However, the official vote showed the Republican candidate, George W. Bush, slightly ahead. With the disenfranchisement of 40,000 African-American voters who likely would have voted strongly for Gore and the invalidation of many ballots where the vote for Gore was not punched completely through, a recount was requested. When it looked like a full recount might swing the advantage to Gore, Bush asked the Supreme Court to stop the recount—which it did, along party lines, thus awarding the Presidency to Bush. The mainstream media fully reported what happened but did not go further to investigate what many continue to claim was a political coup.

Then, in the 2004 election, election night exit polls showed that Democrat John Kerry had won Ohio and the election. The head of the company that made the voting machines used in Ohio, John Diebold, had publicly stated that he would do whatever was necessary to assure Republican George W. Bush’s re-election. When the results from the voting machines in Ohio were reported, they had Bush winning the state and the Presidency. The media reported the facts but appeared to do no investigative reporting. Are exit polls misleading and, if so, should they be banned? Do the media have a responsibility to go beyond reporting the facts and seek to determine and inform the public why an event happened, as was done during the Watergate affair? Are the brief and headline nature of electronic media news preventing the in-depth reporting that is necessary for informed public opinion in a democratic society? These were questions asked by many both inside and outside media circles.

Fig 10.2 According to the NAB, local broadcasters give the audience ample political coverage.

Courtesy NAB.

The 2008 Presidential election was another milestone in U.S. politics. For the first time, the Presidential candidate of the Democratic Party would be an African-American or a woman, and for the first time the Vice Presidential candidate of the Republican Party would be a woman. This prompted extensive and intensive media coverage of both the primary and final campaigns. As with its other news operations—this time, for obvious reasons, more intensely—the media concentrated more on the personalities than the policies of the candidates. The power of the media—particularly television—as a critical political factor was manifest. Voters saw on television the Democratic Presidential candidate, Barack Obama, as a confidence-inspiring orator. Conversely, Republican Vice Presidential candidate Sarah Palin appeared uninformed and misinformed in early live interviews and immediately was withdrawn from such media exposure.

Criticism from some quarters continues to take media news to task for its naïve and compliant coverage of the outrageous hike in gasoline prices in the second half of the decade. In reporting the day-to-day rise in the price per barrel of oil and the resulting gas station prices of over $4 per gallon, the media did not report the continuing comparative high prices at the pump when oil costs went down. While motorists and auto sales were suffering, Big Oil continued to set records for profits for any industry, in the tens of billions of dollars. Should the media have investigated Big Oil’s profit motive as the reason for high gas prices instead of shifting the blame to the need for more drilling in U.S. protected environmental areas?

Talk radio grew during the decade. While the overwhelming number of radio talk shows were right-wing oriented (for some years there was not a single “liberal” syndicated talk show), toward the end of the decade some liberal commentators reached the airwaves, including a few on cable TV networks. By and large, however, U.S. electronic and print media remained conservative to radical right, and alternative political viewpoints were found mostly on the Internet, through Websites such as Indymedia and FreeSpeechTV and through ever-increasing Web logs, or blogs, posted by ordinary citizens as well as by the famous and powerful. It was not surprising, therefore, that as the decade ended, power brokers were attempting to eliminate “Net neutrality” and give the Internet service providers (ISPs) control over Internet users and content.

Fig 10.3 Web radio receivers make their debut but disappear after Internet radio market flattens.

Courtesy Kerbango.

Music—to the consternation of many radio stations as well as music authors, composers, performers, and publishers—also became an increasingly important part of Internet use. Many students who would be irate if they had written a book or produced a film and received little or no royalties because their work had been pirated and circulated free among prospective audiences or who would promptly sue if any copyright or patent they had registered had been stolen, depriving them of any compensation for their work, had no compunction about pirating copyrighted music downloaded from the Internet, sharing it with or receiving it from friends without paying any fee to the creators and copyright owners. This practice prompted congressional legislation requiring computer and consumer electronics makers to incorporate technology that would prevent downloading music or film that has been copyrighted. Suits by music copyright holders under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act forced hundreds of music pirates to close, a fine for the most prominent Internet pirate, Napster, and prosecution of individual student pirates. Responsible distributors such as Listen, Pressplay, and RealOne Music Pass replaced Napster by paying legal fees for their music and establishing subscription bases for their individual clients. As the decade came to a close, with Internet radio beginning to outstrip terrestrial radio in audience numbers, Internet radio stations joined traditional stations in seeking congressional protection from user fees imposed by music copyright owners.

2000

One prediction of chaos in the new millennium did not happen. A widespread belief was that a Y2K (Year 2000) bug would disrupt and possibly destroy computer communications throughout the world and affect other electronic media as well. Such an apocalypse did not occur on January 1, 2000 (or on January 1, 2001, the technical but less popular start of the new century).

As noted earlier, the big news story of 2000 was the Presidential race, particularly in Florida, because of a confusing paper ballot in some areas of the state, the invalidation of the “hanging-chad” ballots of many older people who had not punched them hard enough, and the suspension of a full recount by the Supreme Court—in effect, the entity designating the new President.

Consolidation saw key mergers in 2000. In 1999 the FCC had approved television duopolies, and the big players lost no time in taking advantage of it. The AOL-Time Warner merger was approved by the FCC and resulted in a $180 billion corporation. CBS-Viacom merged into a $23.8 billion organization. AT&T and Media One’s merger cost $69 billion. Radio’s Clear Channel bought AMFM and was worth $23.8 billion. News Corp (Rupert Murdoch’s Fox conglomerate) bought Chris-Craft, $5.3 billion. Univision, a Spanish-language network, bought USA Networks, $1 billion. On January 1, 2001, Broadcasting & Cable magazine summed up the consolidation frenzy: “The big got even bigger.”

Fig 10.4 Independent media centers have been established around the globe to provide citizens with noncorporate, nongovernmental perspectives on important issues and trends. We are already into global total interactive communications.

Some of the big media players, however, were not so happy. Broadcast television networks continued to lose viewers. Despite this decrease in viewership, however, all four major networks actually made more money. Total broadcast TV revenue reached a record $33.3 billion, a gain of 17% from the previous year. Broadcast’s principal rival, cable, also showed huge monetary gains, up 29% from the year before for a total of $17.4 billion. Cable’s increasing fees, however, lured an increasing number of TV homes to switch to satellite; the average hike for cable bills was 5.8%.

Fig 10.5 Audiences for direct broadcast satellite continued to grow in the new millennium. TiVo also debuted to make certain that viewers miss nothing (except commercials).

Courtesy RCA and USSB and the TiVo Store.

Programming moved in a number of new directions. Ethnic and lifestyle audiences who were not previously fully served were targeted. An all-news Spanishlanguage radio station began in New York City. Not only more news programs but plots and characters on television shows recognized the growing political and buying power of gay and lesbian audiences. Producers and cable and broadcast distributors continued even greater recognition of the potentials of the Internet and planned to go beyond just streaming programs into cyberspace. Film studios explored video-on-demand services but were concerned about finding ways to prevent a movie version of Napster from pirating their feature films for subsequent pirating through file sharing.

Music programming intensified, aimed at teen and college-age audiences, formats and selections concentrating on the GenY “Gotta-have-it-now” short attention span. Interactive music selection increased on the Internet. Pay per music, which helped artists promote their CDs, was not much competition for free, file-sharing pirated music.

At the end of the year there were 4,685 AM and 5,892 FM commercial and 2,140 noncommercial radio stations on the air. Commercial television stations totaled 721 UHF and 567 VHF, with 250 noncommercial UHF and 125 VHF. Low-power TV (LPTV) stations, often neglected (see the 1999 book, The Hidden Screen), continued to outstrip the number of full-power stations, with 1,756 UHF and 610 VHF LPTVs licensed. The two largest cable companies, AT&T and Comcast—which were to merge the following year—had 15 million and 11.7 million subscribers, respectively. Cox was third, with 7.6 million. By the end of the year the FCC had certified 255 eligible applicants nationally for the reinstated low-power radio licenses. Unlike the 10-watt stations abolished 20 years earlier, however, these were for 100-watt power with a radius of about three miles.

2001

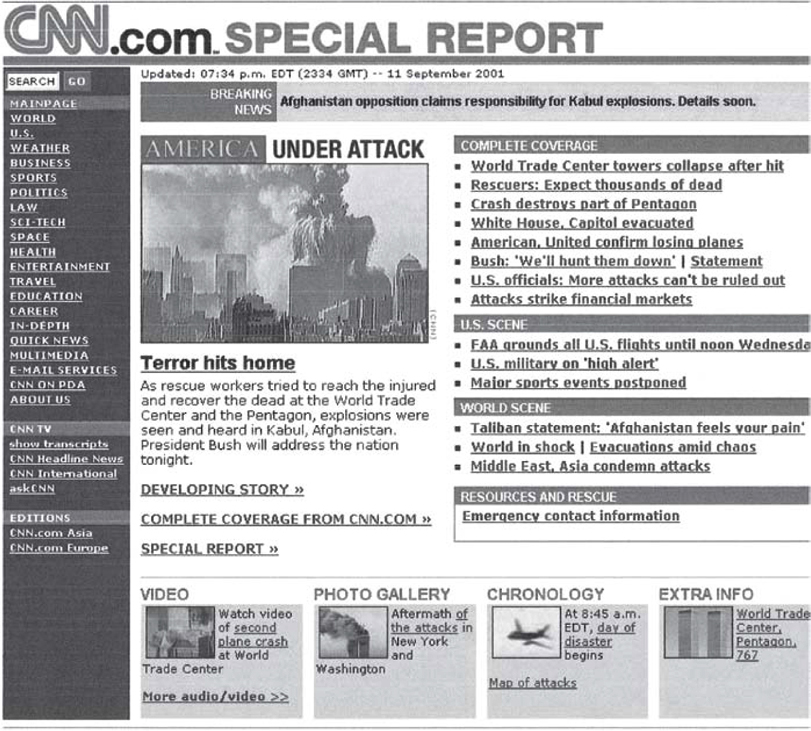

The all-consuming event of 2001, the 9/11 terrorist attacks, presented the media with a new test: covering an unexpected attack by an unannounced enemy on targets on U.S. soil. The major networks and stations responded by preempting virtually all other programming for 24-hour coverage of the attacks and their aftermath at the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and the passenger-aborted hijacked flight that crashed in Pennsylvania. The networks lost between $50 million and $75 million a day in ad revenues. The results of the attacks were graphic, some too graphic for the networks, but CNN and foreign news teams, including those from Canadian stations, showed the horror of victims leaping and falling to their deaths from the highest stories of the World Trade Center. The country later discovered that the enemy was one we had supported and strengthened during the cold war against the Soviet Union. Broadcasting & Cable, politically conservative in its editorial policy, stated that “the shock at the intensity of the hatred toward the U.S. may be attributed to underreporting by TV news programs [of world attitudes toward America’s economic globalization and foreign policies].”

Fig 10.6 The CNN Website on 9/11.

Courtesy CNN.

The media extensively and intensively covered the U.S. attack on Afghanistan, its Taliban government, and Al Qaeda and its leader, Osama Bin Laden. While the destroying of the Afghanistan government and infrastructure appeared to be successful, Al Qaeda and Bin Laden escaped. Having learned how to manage public opinion in the first Gulf War, the Pentagon reinstituted control of journalists’ coverage and psychological attitudes by restricting them to “in-bed” assignments with designated Army units. Reports in the U.S. media differed in a number of substantial ways from reports of nonrestricted journalists representing the media of other countries. Reporting from Afghanistan was not easy for any of the electronic media, however, with the weather—sand, dust, windstorms—frequently knocking out and generally corroding video and audio equipment.

On the home front, a new FCC represented the philosophies of the new administration, with an immediate impact on several key areas of broadcasting. Deregulation moved apace. A key area was consolidation. As Broadcasting & Cable magazine reported, “Powell’s FCC won’t impose public-interest conditions on industry acquisitions, mergers, conglomerates.” Key mergers included the consummation of the AOL-Time Warner deal. Viacom added cable’s BET to its youth- and pop music-oriented holdings such as MTV, VH1, and CMT and its older demographic and ratings-leading network, CBS. Viacom also got FCC approval to own two national TV networks, CBS and UPN. AOL/Time Warner led the big media list, followed by Walt Disney, Vivendi Universal, Viacom, and News Corp. The leading television groups were Fox, Viacom, and Paxson, and the top 25 TV groups owned 44.5% of all U.S. commercial TV stations—up from 41% in 2000 and a huge rise from the 24.6% five years before, in 1996. The top 25 radio groups controlled 24% of all radio stations in the United States and got 57% of radio’s total revenues. In a couple of years AOL/Time Warner would change its name to Time Warner, attempting to revive its media rather than its Internet image. Ted Turner, who in 2001 regretted that he had allowed Turner Broadcasting to merge into Time Warner and who was ousted as an officer when the latter merged with AOL, stated that in the near future he believed that there would be only two huge surviving MSOs and only four or five programmers.

Another area the FCC dealt with was indecency. The new strongly conservative attitude in Washington opened the door again for Morality in Media and right-wing ideologues like Jerry Falwell to pressure the FCC with more success than they had had in more recent years. At the same time, the FCC was pressured by broadcasters and by First Amendment advocates to act with moderation. Rapper Eminem’s song, “The Real Slim Shady,” was generally considered to be in violation of indecency standards. To capitalize on its popularity while avoiding FCC sanctions, stations played a cleaned-up version. The FCC, however, levied fines even for playing the cleaned-up version. A Kaiser Foundation study weighed in on TV drama and sitcoms, stating that two-thirds of all shows have sexual content. The FCC issued guidelines on its enforcement policy regarding indecency, described by its new chair as “a restatement of existing statutory, regulatory and judicial law… establishes a measure of clarity in an inherently subjective area.” The policy statement included examples from programs that the FCC considered indecent and from borderline examples that were judged not to be indecent.

Other programming also came under scrutiny, especially by the public. The surgeon general reported that although TV violence might have short-term influence on behavior, it did not have long-term effects. The media went all out in pursuing “infotainment” —for example, covering the disappearance of congressional intern Chandra Levy with full emphasis on her relationship to Representative Gary Condit, reminiscent of the media frenzy in the earlier Monica Lewinsky–President Clinton story. The most-watched program during the summer of 2001—pre-9/11—was Connie Chung’s interview with Condit. As counterpoint to what many felt was broadcasting’s pandering, a cable channel, Trio, broadcast a 1949 TV presentation of one of America’s greatest theatrical productions with the original cast: Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman.

News coverage, even before 9/11, underwent changes. Early morning, pre-break-fast news shows grew in numbers and audiences. The youth audience was targeted by CNN’s Headline News, which unveiled a new format, a fast-moving, colorful, multisectioned screen with simultaneous different news items, hypergraphics, and a new slogan, “Real News, Real Fast.” Whether it appealed to the computer-savvy generation or not, it wasn’t long before its frenzied nature began to turn off at least older viewers, and CNN modified the new approach. While newscasting largely continued the “If it bleeds, it leads” approach, TV backed off from carrying the execution of Timothy McVeigh, who had been convicted of an act of domestic terrorism, the Oklahoma City federal building bombing in 1995.

Spanish-language programming and TV audiences grew, as did television oriented to women, with the Lifetime channel the cable ratings leader and new channels Oxygen and WE moving up. The quality drama The West Wing, which made a huge critical splash, sold its syndication rights to cable network Bravo for a record price of $1.2 million per episode. Conversely, some syndicators began to look to cable for their first-run shows. A first for a major TV network, NBC accepted liquor ads. An expected expansion of hard-liquor advertising did not materialize and NBC dropped liquor advertising the following year.

The big programming news was the remarkable success of reality shows such as Big Brother, Fear Factor, Weakest Link, and others mentioned at the beginning of this chapter. Survivor continued to be milked by CBS, which readied Survivor 3. A new game show cable network was aimed at younger audiences. More and more programs were streamed onto the Internet. VH1 put albums on the Internet before their release. A study showed that television viewing was the principal victim of Internet growth. Wide-screen digital TV began to have an impact on the market. Radio music station streaming increased even as the government cracked down on Napster and music piracy.

Prime-time TV ratings continued to fall and for the first time in 10 years primetime advertising minutes decreased. Networks blamed the Nielsen rating system. In at least one instance the Nielsen system didn’t work: Its computers “forgot” to adjust their clocks to daylight savings time and, until the error was remedied, reported inaccurate information. The economic recession—mild compared to the one later in the decade—reached the media and layoffs at the networks pushed an increasing number of broadcasters into the growing ranks of the unemployed.

Satellite services grew, providing additional competition for the beleaguered TV networks. DBS subscriptions were counted for the first time in comparison to cable. DirecTV was third overall, behind AT&T and Time Warner, and Echo Star was eighth. To even the playing field with cable, DBS was required by the courts to carry every local TV channel in the markets it served.

Fig 10.7 Plasma televisions add a new dimension to home viewing.

Courtesy Sony.

In radio, Rush Limbaugh reflected the success and dominance of right-wing talk shows when he signed radio’s richest syndication contract: $250 million for eight years, plus a $35 million signing bonus. (Two years later he would be exposed for illegal drug use. Should that have had any impact on his show or his contract?)

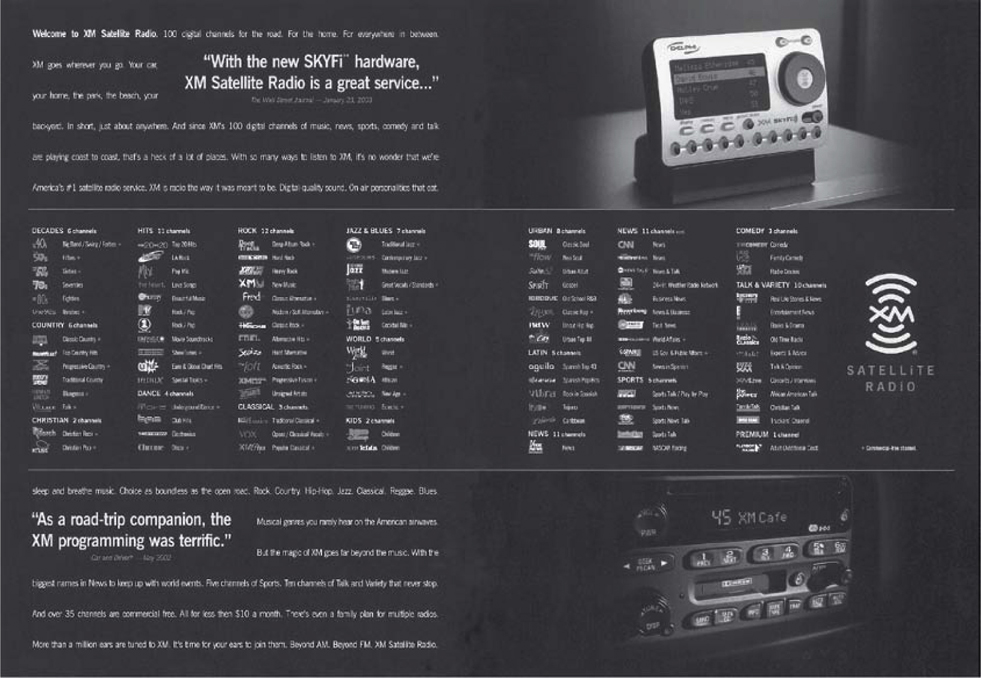

Some sources talked about the reinvention of radio, as satellite stations proposed to offer at least 100 static-free stations with the debut of XM Satellite Radio. The top radio groups in 2001 were Clear Channel, with 1,202 stations in 189 markets and $3.5 billion in revenue; Infinity, with 183 in 41 with $2.3 billion; and Cox a distant third, with 82 in 18 and $455 million in revenue. The National Broadcasting company was 75 years old.

2002

Consolidation! Consolidation! Consolidation! Mergers, acquisitions, and takeovers resulted in fewer and fewer individual owners, larger and larger conglomerates, less and less diversity in programming, and more and more unemployment in the field as the fiscal bottom line became the determinant of media operations and development.

Comcast, following its acquisition of AT&T Broadband, was the largest MSO, with about one-third of all cable subscribers, and generated over $1 billion in ad sales. NBC acquired Telemundo, the Spanish-language network. Expanding Viacom dominated television, not only through its two networks, CBS and UPN, but notably through cable network holdings, which included Nickelodeon and MTV. Viacom reached one-fourth of all U.S. viewers and a fourth of the highly desired 18–49-year-old audience. Spanish-language television was the fastest-growing advertising medium and prompted the subsequent merger of the two largest players, Telemundo and Univision.

Not everyone, however, was happy with the results of consolidation. Unions representing media employees were unhappy with what they felt were fewer jobs, lower quality, fewer media outlets, less diversity, and higher ad prices. The Writers Guild of America argued that consolidation imperiled creativity. The Association for Local Television was forced to disband after 30 years, stating that most of the organization’s members were swallowed up by large conglomerates. The American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (AFTRA) and various record labels decried the giant broadcast groups, alleging that they exerted a form of payola by controlling so many outlets, making it difficult for new and independent artists to get air time and forcing them to go through and pay a small group of promoters. Radio consolidation put two-thirds of all radio revenue into the hands of just 10 radio groups. One of the organizations fighting radio consolidation, the Future of Music Coalition, complained that conglomeration resulted in a “tremendous overlap of songs between supposedly distinct formats” and told the FCC that radio format diversity had become a sham. Even Congress got into the act, blocking a proposed FCC auction of spectrum space that would have allowed a small number of the wealthiest companies to become even bigger.

AOL/Time Warner earned $38.2 billion in revenues; Vivendi Universal, $31 billion; Walt Disney, $25.2 billion, and Viacom, $23.2 billion. The top TV groups in 2002 were Viacom, with 40 TV stations covering 45.4% of all TV homes; Fox, with 34 stations covering 44.7%; Paxson, with 68 stations and 65.9% (many of these were UHF, which were counted as only half, resulting in an FCC figure of 38.1%); and NBC, with 24 stations and 33.7%. In radio, Clear Channels owned 1,238 stations in 190 markets with revenues of $3.2 billion, Viacom 183 in 41 markets and $2 billion in revenues, and Cox 79 in 18 markets and $430 million.

The television network audience numbers continued to fall, and for the first time cable’s share of the audience was more than half, with broadcast television getting only 38.4 at one point in 2002, for the first time dropping below 50%. Nevertheless, NBC remained the top money maker among TV and cable nets. QVC, the home shopping network, crept closer, however, as cable’s highest incomeproducing net.

The three-way fight among broadcasting, cable, and satellite intensified. Broadcasting’s prime-time ratings continued to suffer in comparison to those of the other two delivery systems. Cable subscriptions slipped after some 20 years of continued growth. Satellite subs, at 18.2 million, were two and a half times more than they’d been just four years earlier.

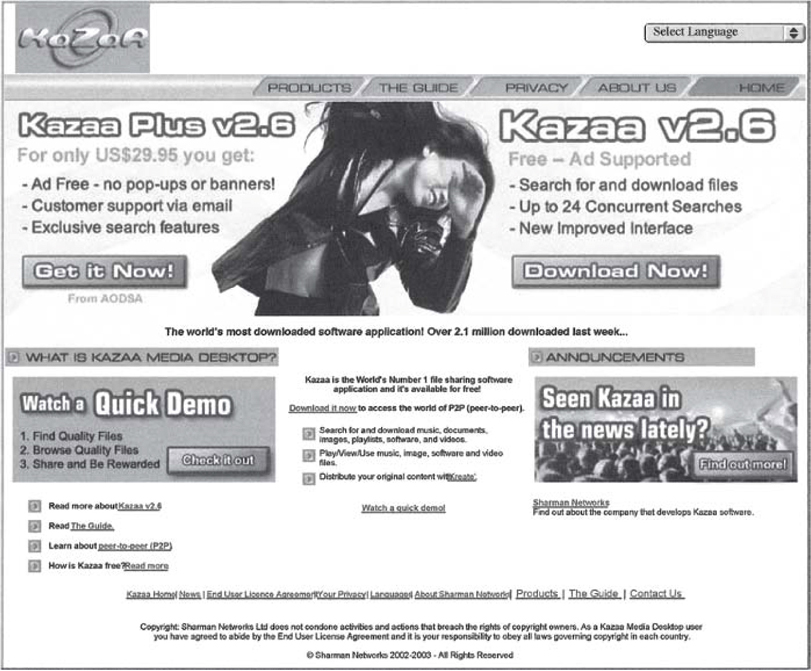

Fig 10.8 New audio listening options have drawn users away from traditional radio.

Courtesy Kazaa.

The aftermath of the 9/11 attacks continued to have an impact on media programming, with the war in Afghanistan leading the news and the public eagerly awaiting fulfillment of the President’s promise to capture the instigator of 9/11, Osama Bin Laden. In the meantime, the White House began pushing for a war on Iraq. Some media critics warned of a “wag the dog” scenario. As noted earlier, the mainstream media gave only cursory coverage to the millions of antiwar protesters in the United States and throughout the world, including protests of hundreds of thousands in Washington, D.C., by the Act Now To Stop War and End Racism (A.N.S.W.E.R.) organization. The media appeared to be more interested in covering the sniper killings in the Washington, D.C., area and other “If it bleeds, it leads” stories.

Original cable programming got more public attention, winning Emmy and Golden Globe awards for several of its series, which included HBO’s Sex and the City, Six Feet Under, The Sopranos, and Band of Brothers. Television talk shows, such as those hosted by Rosie O’Donnell and Sally Jessy Raphael, began to go off the air, replaced by the growing number of reality programs. As noted earlier, costs for reality were almost as low as for talk shows and audience participation shows and were garnering higher rating numbers. The networks also began to push primetime real-life documentaries as a form of reality shows, with The Osbornes a prime example.

Indecency continued as a hot topic. Although Opie and Anthony had been fired because of their St. Patrick’s Day sex stunt, the FCC initiated an investigation into whether the station’s license should be revoked. The St. Patrick’s caper set up a louder chorus of concern, including in Congress, about broadcast program content. Cable was not immune from criticism as more and more of its programs added sex and raw language.

Minorities and women were increasing their criticism of broadcasting’s “old white boy’s club,” which was reinvigorated with the continuing demise of affirmative action. African-American broadcasters, for example, called for rewriting all broadcasting ownership regulations as the only way, in a time of increasing consolidation, to open the way for minority ownership. In 2002 women held only 14% of the top executive jobs and 13% of board member positions at the major media companies. Eighty-four percent of the president and CEO positions at the top 120 broadcast and cable channels were filled by men, 16% by women. The National Organization for Women (NOW) accused the six major networks of catering to an “adolescent boy’s fantasy world” with what it called “a distorted and often offensive image of women, girls and people of color” in network programming.

Technology made strides in both television and radio. Sirius satellite radio made its debut as a competitor to XM and ended the year with 261,000 subscribers. XM ended the year with 1.36 million subscribers and planned to offer commercial-free music channels in 2004. The FCC mandated digital tuners in all television sets by 2007 as HDTV digital service became available in an increasing number of markets. Some broadcasters were looking at low-power TV as a way of reducing digital transmission costs. With increasing consolidation, increased automation reached into both television and radio control rooms, saving money and increasing profits by reducing personnel.

There was controversy about streaming TV and radio signals onto the Internet. Although broadcasters understood the long-range need to get onto the Internet, some TV executives wanted their signals kept off because they believed that an Internet presence diluted their current advertising base. Radio executives wanted Internet streaming but were concerned that copyright royalty fees were too high. Nielsen ran into a buzz-saw in Boston when stations dropped its service because they objected to the cost and distrusted the accuracy of the new “people meter.” It would be a while before the parties came to a new agreement. Though this book does not list all the prominent people in broadcast history who died in a given year, the man known as Mr. Television, Milton Berle, credited with unique contributions to the rapid growth of early TV, died at 93.

Fig 10.9 An index of XM Radio programming.

Courtesy XM Radio.

Theoretically, HDTV has no Relationship with DTV

When digital television was receiving a lot of attention prior to the DTV transition, it was frequently conflated with HDTV, and there is evidence that many consumers wound up purchasing a more expensive HD set when all they wanted was a receiver that would work in a digital environment. There is actually no relationship between the two. Whereas digital is relatively new, HDTV has been around since the late 1960s, when Japan developed MUSE, an 1,125-line picture (even greater resolution than today’s HDTV) using analog signals. However, the more lines transmitted, the more bandwidth needed. With analog that simply wasn’t realistic, but in a digital era extra signal information can be conveyed using the same spectrum space. But it is not even clear what qualifies as high definition. The National Television Systems Committee 525-line standard had been the norm for well over 60 years. Presently some stations broadcast in 720, others in 1,080, and both are termed high definition. And some employ both, choosing the higher resolution for programming such as live sporting events that augments the experience, and the lower variation for daytime talk or game shows that don’t really benefit from enhanced images.

2003

This was another year of vicissitudes. War, a blackout of the Eastern United States, the disintegration of the Columbia space shuttle, continued media consolidation and job losses, a failing economy punctuated by continued corporate looting of investors’ funds, FCC virtual elimination of ownership caps, and, in two states in particular, Illinois and Massachusetts, final-second dashed hopes for at-long-last World Series bids by the Cubs and the Red Sox.

Despite the opposition of millions in the United States and most of the rest of the world, the U.S. invaded Iraq. After President Bush announced that the war was over, more U.S. military personnel continued to be killed than had been killed during the war. The networks hurried to cover the conflict, but, as in the Gulf War of 1991, found it difficult because of the embedding of journalists within military units. CBS newsman Dan Rather observed that “As journalists, we have to realize there’s a very fine line between being embedded and being entombed … there is a way to cocoon the journalists and place them in a position so they only report what the top tier of the military wants reported.” It became difficult for the media to give the public an accurate picture of what was happening. Broadcasting & Cable magazine noted, “It’s been hard … for the networks to find a focus; all those pieces of war footage from a small army of embeds never makes a whole pie.” As in the Vietnam era, those who were critical of the administration’s actions were called un-American, and some of the media clamped down on America’s tradition of freedom of speech in ways reminiscent of the 1950s McCarthy era. For example, one highly popular singing group, The Dixie Chicks, whose members criticized the administration’s war on Iraq, had their songs banned by many stations and were dropped by the Cumulus conglomerate.

Later in the year the media’s reportorial freedom was facilitated to enable them to report what the administration proclaimed as a key accomplishment of the war, the capture of Iraq’s leader, Saddam Hussein. CBS radio reported it first to the American public. Dan Rather followed about an hour later on CBS television, staying on the air, as one newspaper noted, “an awesome six hours.”

Throughout the year media program directors and news divisions gave priority to significant events, sometimes even at the expense of entertainment program advertising revenues. In February it was the loss of the space shuttle Challenger as it reentered the earth’s atmosphere. In August a huge, extended Northeast blackout precluded any reception that required electricity, although newsrooms had backup generators and continued their coverage. Battery-powered radios played a key role, enabling radio stations to provide information to the public on this largest power blackout in U.S. history. True to its bottom line, however, the media also went overboard with seemingly unending coverage of events such as the California gubernatorial recall and election, giving its headlines to a Hollywood actor without government experience whose publicity and image resulted in his election; to the disappearance and murder of a pregnant housewife; and to the return of a young woman kidnapped and reportedly held hostage by a cult-type figure.

In other programming areas, reality shows continued to dominate. At least two networks began to shuffle around their drama programs to find scheduling slots more conducive to their survival in the competitive waters of reality shows. The reality show Survivor was getting $425,000 for a 30-second commercial; two top drama shows, CSI and Raymond, were getting $400,000 for a half-minute spot. Key live sports events continued to garner the highest ratings and advertising dollars.

Ethnic programming grew. A new African-American cable channel, TV One, was announced as a new competitor to BET. The millions of viewers who watched Spanish-language TV now could watch new programs in the most popular format, the telenovella or soap opera, oriented to their personal experiences. Competitors Telemundo and Univision both launched shows produced in the United States rather than in Latin America or Spain, reflecting their viewers’ lives in the North. Their competitiveness became moot later in the year, however, when they announced their intention to merge. Cable channels oriented to programming for women expanded, with Oxygen, We, and SoapNet all showing gains of millions of viewers. But even their successes didn’t deter their joining the rush to cloning. WE announced its plans to add three new reality series. Nonstereotyped gay and lesbian characters increased on TV shows. On a popular youth-oriented series, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, network TV had arguably its first lesbian sex scene.

The shock-jocks and indecency saga continued. The FCC fined Infinity Broadcasting $375,000 for the 2001 Opie and Anthony St. Pat’s sex caper and threatened to revoke its licenses for future infractions. The FCC also fined an Infinity radio station in Detroit the maximum amount, $27,500, for one indecency transgression on one station, citing a show in which the host and callers allegedly described explicit sexual techniques and physical assaults on women in an “extremely graphic, lewd and offensive” manner. In a ruling confusing to some, the FCC found that U2 singer Bono’s on-air use of the “f” word (“this is really, really fucking brilliant”) didn’t violate indecency rules and “may be crude and offensive but, in the context presented here, did not describe sexual or excretory organs or activities.”

Civil liberties groups such as the ACLU and performers’ organizations such as AFTRA objected to the White House, Congress, and FCC policies. Many critics and media professionals attributed the new restrictions to what they believed was a continuing erosion of First Amendment guarantees of freedom of speech, press, and assembly under the George W. Bush administration, including the government’s use of the PATRIOT Act and FBI efforts to stifle dissent. The issue of indecency appeared to permeate America’s consciousness and media coverage.

The FCC was consistent in its policy of expanding consolidation. It removed more multiple ownership caps, allowing one owner to reach 45% (up from 35%) of the public; routinely waived the cross-ownership newspaper-broadcast station ban; and okayed TV duopolies for smaller markets and triopolies (owning three or more TV stations in a market) in others. A federal court stayed the 45% expansion, and although the Senate voted for a rollback to 35%, the threat of a Presidential veto placed the issue in temporary limbo. Consumer groups, including the longactive Media Access Project, challenged the FCC’s new rules and a federal court put the new rules on hold as the FCC filed its own counter-appeal. One of the mergers consummated in 2003 was Rupert Murdoch’s (News Corp/Fox TV) acquisition of DirecTV.

In further catering to commercial interests, the FCC banned noncommercial applicants from applying for unreserved radio channels, restricting the noncommercial and public stations to the 20 channels reserved in the 88.1–91.9 FM spectrum. In late 2003 the FCC gave TV stations that had not yet installed DTV/digital just six more months to comply under threat of license revocation. The FCC also angered media companies by raising its regulatory fees for broadcast radio and television, DBS, and cable.

Many programmers who didn’t do well continued to blame it on the rating systems. The president of the Cable Television Advertising Bureau, Sean Cunningham, stated that “Nielsen’s diary/meter methodology is widely believed to under-report cable viewership by 25% to 50%.” The expansion and use of local people meters in a number of top markets (Boston, a holdout, finally agreed to a people meter contract) muted some of the criticism. Many broadcast TV stations and cable systems in particular experienced rating increases. In addition, the local people meters measured demographics to a much greater extent than the passive meters and diaries. DBS continued to gain on cable and broadcasting, adding 1 million subscribers in 2003 for a total of 10.6 million. Amid many broadcasters’ cries of gloom and doom, CBS celebrated its 75th anniversary. One note of gloom was the death of the venerable radio and television performer, Bob Hope.

The conservatism of the country’s political leaders and media owners appeared to impact programming. MSNBC fired one of the long-time leading liberal talk show hosts, Phil Donohue, and replaced him with radical right-winger Michael Savage to join other MSNBC right-wing personalities Alan Keyes and Pat Buchanan. The national trend was to increasingly conservative talk shows, with the few liberal talk hosts being fired and late 2003 finding not a single liberal talk show with national syndication. John Leland wrote in The New York Times that compared to Republicans and conservatives, Democrats and liberals have a “yammer gap.” In 2003, however, two of the right-wing’s darlings of talk radio were caught with their pants down. Republican Party star commentator Rush Limbaugh had for years excoriated many individuals and groups who didn’t agree with him and was particularly harsh through a holier-than-thou approach to lawbreakers such as drug users. Ironically, it was revealed that he had been illegally purchasing and using drugs himself for years. And conservative Paul Harvey, in a moment of candid religious bigotry, said on the air that Islam “encourages killing,” spurring demands for an apology by civil rights groups. To counter the right-wing dominance of talk media, a new group, Progress Media, announced in late 2003 that it planned to buy stations in major markets for an Air America Network and institute liberal talk shows. Robert Kennedy, Jr., and author and comedian Al Franken were among the first hosts signed, with Franken commenting, in reference to competing with Rush Limbaugh, that “I’m going to try to do [the show] drug free.” In early 2004 one liberal talk program, The Ed Schultz Show, began syndication by Jones Radio networks in association with Democracy Radio.

Talk radio also experienced a longstanding gender gap, with relatively few women talk show personalities. Few of these shows were syndicated. Of the local shows run by women, almost all were politically conservative.

Public radio received a huge boost in 2003 when the will of Joan Kroc, the widow of the founder of McDonald’s restaurants, bequeathed $200 million to National Public Radio (NPR). On the public television side, PBS announced that it will allow 30-second underwriting spots, up from 15 seconds. On an even sadder note, one of its former mainstay performers, Fred Rogers (of Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood) died.

Despite advancing technology, consolidation fiscal efficiency, format changes, and economic losses and gains, perhaps one of the most significant comments regarding the state of the media, specifically television, came from Newton Minow, who, as chair of the FCC in 1961, coined the phrase “vast wasteland” in describing TV programming. In an article in the Federal Communications Bar Journal in 2003, Minow said that, if anything, the wasteland was now even vaster and that the FCC is to blame because of its laissez-faire attitude toward regulation and consolidation.

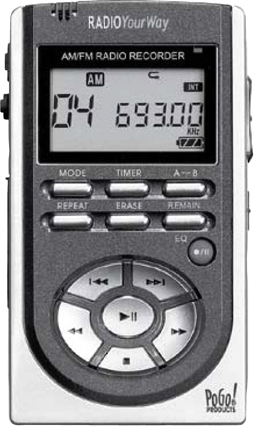

Fig 10.10 Radio programs need never be missed with the RadioYourWay recorder. Performing much like TiVo, this device allows listeners to hear programs they cannot listen to in real time or have missed.

Courtesy RadioYourWay.

2004

The electronic media, with the principal exceptions of C-Span and some public broadcasting stations, appeared to give minimal coverage to the Presidential election primaries. Radio showed its versatility by carrying, in early 2004, the first radio-only debate of Presidential candidates since 1948.

CBS charged $2.3 million for a 30-second spot on the 2004 Super Bowl broadcast. While joining other broadcasters in complaining about government deprivation of some of their First Amendment rights, CBS did an about-face with others’ freedom of speech and refused to carry a paid ad from Move On (an ad that called attention to the trillions of dollars of the Bush administration’s budget deficit that future generations would have to pay for) during the Super Bowl on the grounds that it didn’t wish to air political ads. In what appeared to be hypocrisy, the network did, however, carry a political spot from the Bush White House. CBS refused, too, to carry an ad from People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), the animal rights organization.

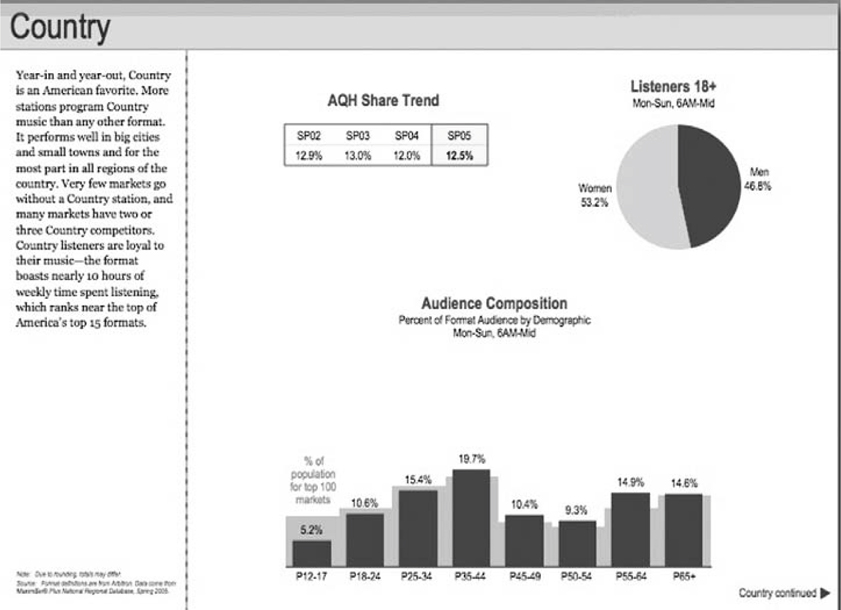

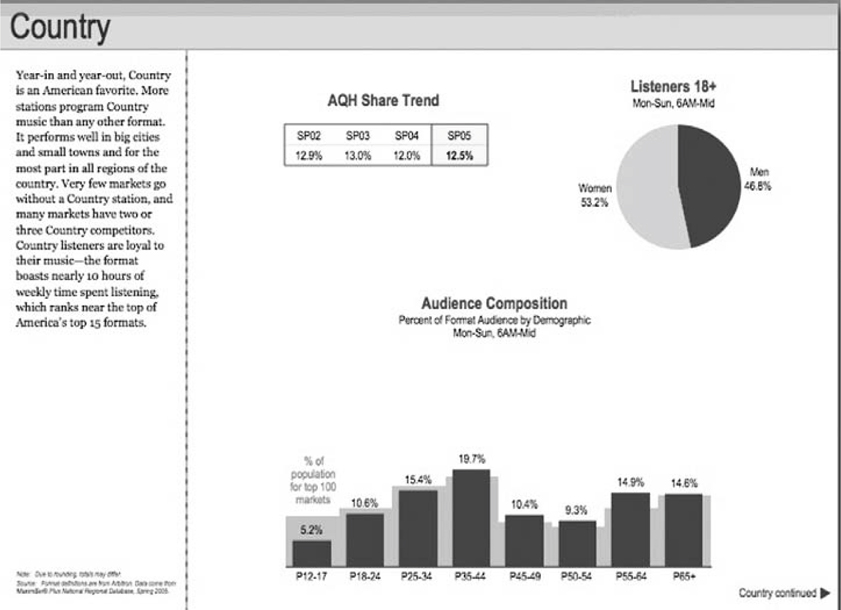

Fig 10.11 Country format remains hot mid-decade.

Courtesy Arbitron.

In early 2004 the FCC fined Clear Channel $755,000 for multiple airings of “sexually explicit” material on its Bubba the Love Sponge show. Clear Channel fired Bubba the Love Sponge. The incident that sparked the greatest commotion, however, was one that the majority of the American public, in a survey, considered “no big deal”: Singer Janet Jackson briefly and partially bared a breast during the half-time entertainment show at the Super Bowl. The “wardrobe malfunction” galvanized conservative groups, members of Congress, the White House, and the FCC, which received hundreds of thousands of complaints. Complaints of alleged indecency on other programs resulted in a sudden spate of fines by the FCC and the removal from the air of several shows and their hosts. The FCC, succumbing to pressure, reversed itself on cases that it had previously ruled were not indecent. Congress was working on legislation that would raise the fine for indecent programming to $500,000 from $17,500 per incident for both the station and the performer. A number of group owners and individual stations cracked down on their shock-jock personalities, some proclaiming a zerotolerance policy. Clear Channel, for example, removed the Howard Stern Show from its stations. Some other owners were not so quick to take action, Zeo Radio president Scott Thomas stating that “new legislation and government involvement will create a much more bland, less compelling radio experience for our country.”

The FCC reversed itself on the Bono F-word ruling and, under increasing public and congressional pressure following the Janet Jackson incident, levied a fine for the fleeting utterance. Is there a way to maintain freedom of speech and at the same time protect young audiences from psychologically harmful material? It is important not to look at the “indecency” controversy as simply a tug of war between Howard Stern and a religious evangelical.

The FCC opened a formal inquiry into violence on television and imposed higher quotas on stations for children’s programming.

In 2004 Comcast attempted a hostile takeover of Disney, bidding $66 billion for the company. Rupert Murdoch predicted that in three years—by 2007—there would be only three huge media companies: his own News Corp, Time Warner, and Comcast. Murdoch did indicate that he thought several “very good and well-run” smaller media companies, such as Cox Communications and Echostar, would remain, but he specifically did not mention Disney, Viacom, NBC Universal, or Sony, all major players at the beginning of the new century. While his trend prediction was accurate, the economic disaster in the latter part of the decade precluded, at least temporarily, his anticipated mass consolidation.

As mentioned, in early 2004 one liberal talk program, The Ed Schultz Show, began syndication by Jones Radio networks in association with Democracy Radio. However, right-wing talk hosts such as Bill O’Reilly flourished in an increasingly conservative political atmosphere. Not only right-wing shows, as expected, went along with the administration’s “terrorist” scare tactics to galvanize public support for its war activities; the media in general did so as well. TV talk shows grew with an increase in younger, more affluent demographics.

Program genres and specific shows that rose to popularity at the beginning of the decade continued their ratings dominance, including The Apprentice, American Idol, CSI, Survivor, Without a Trace, Friends, Law and Order, Two-and-a-Half Men, and Everybody Loves Raymond. Top advertising came from the auto, pharmaceutical, financial products, and media and telecommunications industries. By 2009, the auto and financial sectors were in shambles and traditional media were fighting to survive. Adult cartoons thrived in prime time. Hispanic television grew in terms of audience, programming, and revenue. Local television and radio broadcast stations were lauded for their on-the-spot coverage of hurricanes Charley and Francis in Florida, staying on the air while cable systems were generally disrupted. In network news programming, Brian Williams assumed the reins of NBC Nightly News from retiring longtime anchor Tom Brokaw in December.

Cable viewing was up, broadcast viewing was down, and more and more video was coming to cyberspace. Cable and phone companies were increasingly invading each other’s territory, cable companies making more inroads into phone service and phone companies into video services.

The new Nielsen local people meters (LPMs) generated broadcasters’ rising anger as they showed lower audience figures for both network and syndicated programs.

2005

Reports of disasters dominated broadcast news in 2005. When Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans and nearby areas, broadcast stations in New Orleans were largely destroyed, with station WWL predominantly able to stay on the air. Coverage was principally by satellite. The media did less well in advising the public of the federal government’s lag in providing aid and its apparent lack of concern with the continuing plight of the city’s residents, primarily those who were poor and black and without personal resources to rescue themselves or their property. Earlier in the year media news devoted more time and effort to a foreign news event than it usually did, reporting on the tsunami disaster in Asia that affected countless communities and hundreds of thousands of lives. Coverage of hurricanes and other natural disasters was a public service that resulted in the loss of advertising revenue for stations and networks.

In the political and war area, the media refrained from investigating or reporting on the alleged manipulation for the invasion of Iraq but instead carried news packages distributed by the White House that promoted President Bush’s political and war agendas. While not criticizing this illegal procedure—the federal government, by law, may not operate a domestic broadcast station airing to the public—the FCC did express concern over “prepackaged news” stories and threatened a fine, license revocation, or even imprisonment for not revealing the source or sponsor. While promoting the White House’s policies, the media largely ignored the increasing antiwar protests.

In other programming areas, reality shows proliferated, some successfully, others embarrassingly. However, a problem loomed for reality programs, with writers, editors, and producers stating that they wanted representation by the Writers Guild of America. Dramas such as CSI and Law and Order were highly successful. Other top programs were Desperate Housewives, American Idol, CSI, Everybody Loves Raymond, Without a Trace, and Survivor. Leading the network ratings, in order, were CBS, ABC, NBC, Fox, UPN, WB, PBS, and Pax. Pay-TV nets, in order, were HBO, Starz, Showtime, and Cinemax. But criticism of Nielsen ratings continued, with a number of small market stations discontinuing the service, questioning its accuracy and high fees. The top media companies in 2005 were Time Warner, Disney, Viacom International, News Corp, and Comcast.

Fig 10.12 Reliable network programs continue to attract viewers.

Courtesy NBC.

With virtually no mainstream media news, drama, or sitcoms challenging political authority, The Daily Show with host Jon Stewart drew young audiences by doing so, often in a comedic or sarcastic vein. N.Y.P.D. Blue, groundbreaking in its frank sexuality and realistic language, went off the air after 12 years. However, a new series that turned out to be one of the most effective in TV history to present strong alternative viewpoints on a myriad of real-world issues, be consistently candid in its political criticism, and make people think, David Kelley’s Boston Legal, made its debut.

In terms of content, Congress and the FCC turned up the heat on what they considered indecent programming.

Cable and broadcasting continued their rivalry, with cable viewers once again topping broadcast audiences. They renewed their battle on broadcast-to-cable retransmission payments and on digital must-carry requirements. Both, however, began to prepare for the eventual switchover from analog to digital by using HDTV camcorders.

On the legal front, the federal court again asked the FCC for a rewrite on its ownership rules—the third such request in six years—as consolidation continued to grow. There was increased concern with piracy of copyrighted material through illegal downloads. What eventually would be the biggest concern for broadcasting and cable, however, was in the new media and advancements in technology. Demands for video on demand (VOD) and video online (VOL) presaged what was to come. Convergence—combining two or more previously discrete communication systems—which was virtually dormant after the dot-com crash earlier in the decade, revived. TV stations pushed to reformat their news for the Internet and mobile phone reception. Videos on cell phones heated up. Online programmers now included Cinemax, CNN, CNN International, College Sports TV, E-online, Fox News Channel, GSN (network for games), HBO, TBS, Turner Classic Movies (TCM), Women’s’ Entertainment (WE), TV Guide, and the Weather Channel.

Fig 10.13 Radio still boasts great reach.

Courtesy Arbitron.

Eddie Fritz, NAB’s longtime president who was about to retire, made a farewell address to the 2005 NAB Radio Show in which he lauded localism in radio, noting particularly the medium’s coverage of Hurricane Katrina. At the same time, he and NAB supported the FCC’s increased deregulation of multiple ownership rules, which would permit increased consolidation and the decrease of localism in radio. (For further discussion of localism, see The Quieted Voice: The Rise and Demise of Localism in American Broadcasting.)

2006

The year 2006 continued the gradual and inexorable movement of video and audio to the Internet, with an increasing number of programs from both broadcast and cable streaming to or prepared for online distribution. Nielsen began to extend its research to the Internet. Cable companies added to the growing number of video games online. The big players—companies and programs—continued their domination. The largest income producer was CBS, followed by QVC, ESPN, ABC, NBC, HBO, and Fox. Fox marked its 20th anniversary, its hit programs ranging from Beverly Hills 90210 to American Idol (which was achieving record audiences) plus key sports coverage, confounding critics who predicted it would not succeed. Even while the U.S. economy showed signs of debilitation, U.S. TV grew worldwide, with international distribution and revenue up sharply. Domestically, many stations moved away from syndication and began programming their own shows. One new network, CW, debuted, a merger of UPN and WB, with youth-oriented programming.

Critics’ top programs in 2006 were, in drama, Lost, 24, and The Sopranos; in sitcoms, The Office, My Name Is Earl, and Scrubs; in reality shows, American Idol, Amazing Race, and Project Runway. Most popular programs included Two-and-a-Half Men, Desperate Housewives, and Gray’s Anatomy. Seinfeld went into heavy syndication. The West Wing, one of the very few shows that dealt with real-world issues and gave an acceptably candid inside view of Washington and White House politics, went off the air after eight seasons. Game and magazine shows rose in the ratings. In preparation for the eventual changeover to digital, more and more shows went into high definition. In other areas relating to new technology, the MTV networks competed with iTunes, Telemundo competed with Univision by pushing online programming, and networks reached out for interactive text messaging to shows and participants. Under increasing criticism from users, Nielsen announced that it was phasing out all paper logs and would use only electronic measurements by 2011.

Congress and the FCC toughened their stances on what they perceived as indecency on the air, Broadcasting & Cable magazine describing the FCC’s actions as “a full-frontal assault.” The Broadcast Indecency Enforcement Act of 2005—enacted in 2006—boosted the maximum fine for indecency to $325,000 (from $32,500) per utterance, up to $3 million per incident. Censorship of political content through outside pressure as well as self-censorship of possibly indecent content was illustrated by the History Channel’s canceling of a scheduled documentary entitled Ottoman Empire: The War Machine, even after heavy promotion. The program included material on the genocide of more than a million Armenians by the Turks during the 1915–1923 period, an event that Turkey strongly denies.

Media news suffered as budgets were tightened. There were fewer world correspondents and more outsourcing for local news. Coupled with more people getting their news online, this did not bode well for broadcasting or cable. Nonetheless, the traditional media did a good job of covering the actual events of Hurricane Katrina, although, as noted earlier, it did not do much regarding the selective and arguably prejudicial abandonment of many of its victims. A landmark event occurred in network news in September when Katie Couric (formerly of NBC’s Today Show) became the first solo female to assume the anchor’s position of the CBS Evening News, replacing the beleaguered Dan Rather. The same month that this change took place saw a number of “specials” marking the five-year anniversary of 9/11. One of the media’s “frenzy events” was the revelation of film star Mel Gibson’s anti-Semitism when he was arrested for drunken driving, with personalities like Oprah Winfrey, Barbara Walters, and Larry King denouncing him while others like Bill O’Reilly staunchly defended him and sought notoriety interviews.

By and large journalists have long been considered in the forefront of not only bringing information to the public but in revealing the truth, no matter how disturbing. Many have risked their lives to do so, especially in wars. For example, in 2006, 73 journalists had been killed covering the Iraq War, compared to 66 in the Vietnam War, 68 in World War II, and 17 in the Korean War. Nevertheless, by being embedded with the U.S. forces in Iraq and the previous Gulf War, journalists made themselves vulnerable to censorship, with the public getting almost exclusively the administration’s political point of view regarding the war. Are there approaches to covering a war, especially an unpopular one, where objective and thorough reporting is possible, the government not unfairly criticized, the lives of the troops not endangered, the media’s bottom line not destroyed, and journalists acknowledged for their courage and professionalism?

2007

Convergence continued to affect radio, television, and cable, with increasing online video requiring changes not only in production and delivery systems but in corporate planning for the future as well. Old media were making more connections with the new, including popular venues such as YouTube; Comcast, for example, teamed with Facebook. Broadcasters, increasingly adapting to ever-new technologies such as the growing mobile-TV sector, continued preparation for the transition to digital, with HDTV a predominant subject of discussion at media conferences.

Fig 10.14 TV Guide enlarges its cover if not its readership.

Courtesy TV Guide.

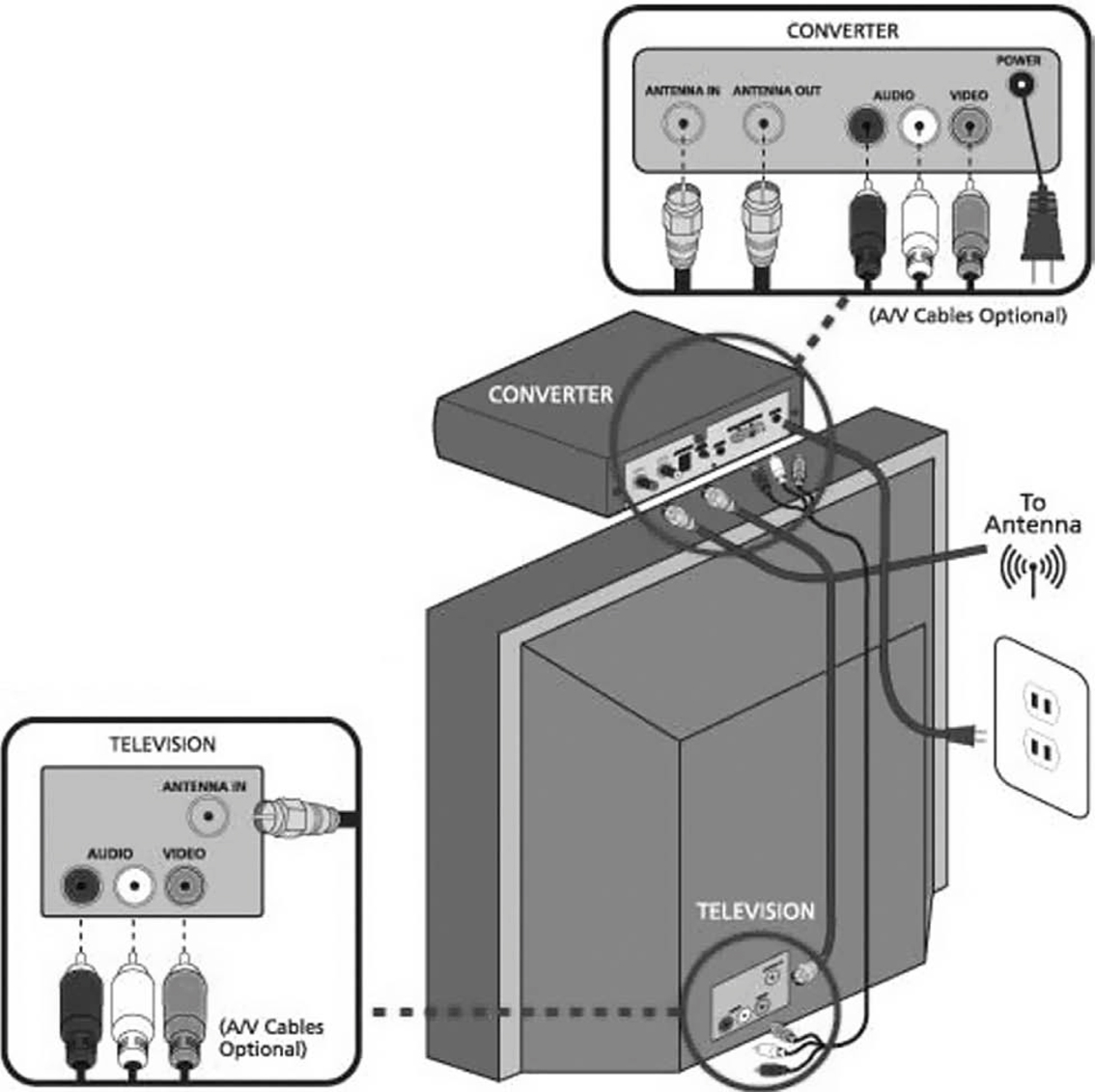

Following the DTV Transition

The digital transition was the most momentous transformation in television history. Prior innovations, such as color or UHF, never posed a total loss of reception. Homes connected to cable or satellite relied on their suppliers to handle the conversion so that they didn’t need to take any additional measures. But the nearly 20% noncable/satellite households and the approximately 40% of connected homes that still used antenna TVs had to either go entirely cable/satellite, purchase a new digital set, or procure, with part of the cost defrayed by government coupons, an external digital tuner. Three months following the changeover and considering the enormity of the endeavor, it has to be considered an overall success. But glitches persist, perhaps the most insidious being with VHF, former prime real estate, often proving ineffective in handling digital without a power boost. But to do so could interfere with other users, prompting a number of broadcasters opting to switch to the previously more spacious UHF only to find that the FCC had sold off chunks of this band. And UHF needs even greater power to match the reach of VHF. All this served to perplex viewers trying to locate their favorite station and choose the correct antenna.

Ratings for even top shows such as American Idol and Desperate Housewives fell in the 2006–07 season. Station groups that reached the most U.S. homes were Fox (36.6% coverage), CBS (35.7%), ION Media (31.3%), NBC (30.4%), and the Tribune Company (27.5%). The FCC put a cap of 30% on the number of multichannel video subscribers any cable company could have. Comcast was the highest at 27%. The FCC looked into violence on television. Late in the year the FCC issued rules allowing newspaper and broadcast station cross-ownership in the top 20 markets, with waivers available in smaller markets. A court case had overturned a similar FCC action in 2003, prompting one Senator to call the new ruling “unbelievably arrogant,” and citizen watchdog groups promised to go to court again. Another Senator stated, “Today the FCC failed to further the important goal of promoting diversity in the media and instead chose to put big corporate interests ahead of the people’s interests.” A little more than a year later, that Senator, Barack Obama, would be in a position as President to change the composition of the FCC to serve the public interest.

Spanish-language programming boomed with the growth of the U.S. Spanish-speaking population. Paranormal and horror shows began to have an impact on broadcast and cable programming. A new quiz show, Deal or No Deal, was a hit. Radio talk show host Don Imus created a huge flap with a racist comment about a Rutgers University women’s sports team and was fired—and later rehired. Repeated criticism of television included junk food ads for kids, consolidation impact on localism, and violence in programs.

In November a writers’ strike by members of the Writers Guild of America (WGA) against the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) virtually shut down scripted shows and the industry in general for months. Reality shows had a field day. The issue revolved around the new media; television writers wanted payment for their work that was sold by producers to secondary markets, specifically the Internet.

Fig 10.15 Web radio expands listening options.

Courtesy Live365.

The economic recession and the drop in audiences affected the bottom line at all levels. Media stocks, in particular cable stocks, plummeted, and cutbacks put many career media people out of work. One bright spot was the international market for U.S. syndication, which exceeded $7 billion. XM and Sirius announced a merger of their satellite radio companies; the merger was finally approved by the FCC in 2009.

Media news operations were, as usual, vacillating between coverage of serious events and pandering to frivolity. For the former, the media provided good coverage of the massacre at Virginia Tech University. For the latter, the media made even greater celebrities of people such as Hannah Montana, Paris Hilton, Lindsay Lohan, and Britney Spears—being exploited by them and exploiting them and the media audiences. In the critical area of news that impacted the lives and futures of all Americans, the media dropped the ball. There was considerably less coverage of the day-to-day war in Iraq, although some media did report—but failed to investigate further—the increasing evidence of violations of U.S. and international law in respect to the Iraq War, torture being one of the allegations, by high White House and other government officials.

In a 2007 speech, former CBS anchor Dan Rather criticized the current state of journalism, stating that the profession has “lost its guts,” reminiscent of Variety magazine’s description of the media’s acquiescence to government policy during the Vietnam War as “no-guts journalism.” Rather criticized journalists for their reluctance to question and criticize, if warranted, the politically powerful, and said that journalists have given up their role as watchdogs to become too cozy with people in positions of power in government and the corporate world. He stated, “[I]n many ways, what we in journalism need is a spine transplant,” and he lauded the Internet as “a tremendous tool for not just news” but also for “illumination and opening things up.”

Fig 10.16 Radio malls dot the urban landscape.

Courtesy CBS Radio.

Fig 10.17 People go to the online screen in increasing numbers.

Courtesy Marketcharts.com.

But this “tremendous tool” was beginning to be feared by the rich and powerful, given its ability to organize and galvanize alternative views and even actions that might challenge the controls of the rich and powerful. The issue of Net neutrality—continuing as this is written—came to the fore, with beginning attempts to try to give the ISPs the power to decide who and what content may have online access and whether limits may be placed on free speech and First Amendment rights in regard to the Internet. (The new FCC chair in 2009, Julius Genachowski, stated that the Commission must protect an “Open Internet.”)

Fig 10.18 More HD stations enter the airwaves.

Courtesy HD Radio.

Fig 10.19 The goal is everything in a box.

2008