Chapter FIVE

The Fearful

Broadcasting and Blacklisting—A Decade of Shame

The Cold War that followed the “hot war” of 1939–1945 generated continuing audiences for media news, with the media exulting in their exacerbation of the confrontational atmosphere between the United States and the Soviet governments and people. The 1950s were a time when demagoguery and fear were rampant, both resulting from and engendering the rise of a U.S. Senator from Wisconsin, Joseph R. McCarthy, whose accusations alone mandated condemnation and ostracizing of thousands of Americans. The atmosphere of McCarthyism allowed labels such as “Commie,” “Red,” “pinko,” “fellow traveler,” and others to cause people’s loss of jobs, expulsion from organizations, eviction from homes, incarceration, and, in some cases, suicide. No proof or trial was necessary. Guilt by accusation became the norm. So strong was McCarthy’s power that even the World War II hero General Dwight D. Eisenhower, running for President, acquiesced to McCarthy’s bidding in speeches and actions and, once he became President, was still not willing to stand up to McCarthy.

It was no wonder, then, in this national environment of fear, that the broadcasting networks capitulated to an organization named American Business Consultants, later called AWARE, that published in its newsletter, Counterattack, and in its 1950, 215-page report, Red Channels, the names of performers, writers, directors, and others in the communications field whose political views it considered “subversive.” Red Channels was officially titled a “Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television.” Among the 151 persons listed therein were some of the outstanding artists of the time, ranging from Aaron Copland to Arthur Miller and Orson Welles.

After some initial protests by a few broadcast executives, broadcasting not only acquiesced but fully cooperated with the blacklisters. All the networks agreed to blacklist the people listed and to pay the blacklisters fees to check the names of all prospective talent on their programs. No proof of subversion was offered and none was required. The New York Times critic, Jack Gould, wrote that “Red Channels is the Bible up and down Madison Avenue.” Hundreds of people’s careers were ruined, and many others didn’t work in their professions for many years solely because of the accusations or innuendos, most of them unproven and undocumented. Accusations accepted by broadcasting as proof of subversion included such things as having opposed the fascist dictator Federico Franco during the Spanish Civil War, having aided refugees from Hitler, supporting repeal of poll taxes, contributing to the elimination of racial discrimination, advocating civil rights, and backing the improvement of relationships between the United States and the Soviet Union. Even some performers who supported blacklisting were blacklisted, not knowing why, unaware that because their names had become confused with or sounded like some others on the blacklist, the networks were afraid to hire them, too. The networks even submitted the names of child actors and actresses to the blacklisters to be checked for possible subversive activity.

JOHN RANDOLPH

TELEVISION, RADIO, FILM, AND TONY AWARD-WINNING STAGE ACTOR

There was a dark phase in television from 1950 to 1965—when the Cold War had the world in its icy grip. The word blacklist came into our language with terrifying results in the communications industry. Hardest hit were the actors, writers, and directors. The networks and affiliates on every level crumbled under the pressure of self-appointed patriots, who wrapped themselves in the American flag. The union leadership in AFRA [American Federation of Radio Actors] and in SAG [Screen Actors Guild] collaborated with the witch-hunt hysteria that swept the land. TVA [Television Authority], the umbrella group that covered the new field of television, included SAG, AFTRA, and Actors Equity representatives. A special committee was elected by the membership at a TVA meeting to investigate blacklisting. It was to hold its meetings in closed sessions to protect witnesses. Before the hearings ended a majority of the committee found themselves blacklisted! Two famous directors of hit shows, who testified before that committee about “no-no” lists or “gray” lists that were used by their casting departments, were blacklisted within a week after they testified. The Secretary assigned by TVA leadership to keep minutes for a report to be given back to the membership was the conduit of the union leadership.

Artists who refused to sign the CBS loyalty oath and to testify were put on the list. Added to this list were actors who had been on still another list, which consisted of actors who forgot lines or who were considered troublemakers or whose names sounded like citizens who testified against state or federal investigative committees. This was the so-called “gray” list, which became a general blacklist and included suspected radicals, Communist or Socialist sympathizers, or members of any organization listed as subversive by the U.S. Attorney General.

Here’s the way it worked on one level. All networks followed a general pattern when casting a show. For each character they would submit five to 10 names of performers to be cleared by former HUAC employees. Vincent Hartnett, who claimed to be an expert in this area, published a hate sheet called Aware Incorporated that was distributed to all agencies, officials, etc., in the business. He charged seven dollars a name (handling approximately 100 names a day) and then returned the network’s submissions notated “acceptable,” “questionable,” or “politically unreliable.” When David Susskind, who was producing East Side/West Side, questioned Mr. Hartnett about a nine-year-old child he needed on the show whose name came back marked “politically unreliable,” Mr. Hartnett replied that [the child’s] father had subscribed to the Daily Worker. David Susskind never submitted a list again.

In my own case, on an NBC live show (all major TV shows were live in 1951), I became a victim of a more sophisticated and brutal form of blacklisting. I had a good role opposite Anthony Quinn, and the show was to be aired the next day when Sidney Lumet, the director, was called “upstairs” by a vice president, who told him to fire me immediately. He had been contacted by the Young and Rubicam Advertising agency and had been told that the sponsors of the show, Ammident Toothpaste, had been called by a Mr. Johnson of Syracuse (owner of three supermarkets), who said he would put signs on his store shelves that Ammident Toothpaste supports Communists like John Randolph. When Sidney Lumet explained that he could not replace me without cancelling the show, he was told that he could go ahead with the broadcast, but if he hired me again he was finished at that network. I worked, but it was the last time for years. Later, this story became the basis of an antiblacklist clause that was put into the Actors Equity contract—the first of its kind during the McCarthy era.

The damage to television was enormous. During the next 15 years over 400 actors’ careers went down the tubes. Schools like the famous Neighborhood Playhouse, the Dramatic Workshop at the New School for Social Research, the Actor’s Studio in New York, and the Actor’s Lab in Hollywood were considered hotbeds of radicals, and their graduates were labeled as such. The beginning of the end for blacklisting came by 1965, when liberal and progressive slots were elected in all major unions. The death blow landed when a talk show personality named John Henry Faulk (elected president of AFRA in New York) got blacklisted, fought it for six years, and won a $3.5 million judgment suit against Vincent Hartnett and Johnson of Syracuse. Ironically, Mr. Johnson, who refused to appear in court, was found dead in a motel in the Bronx on the last day of the trial, just as John Henry Faulk’s lawyer, Louis Nizer, had concluded his summation speech to the court.

Fig 5.1 John Randolph.

Courtesy John Randolph.

The first artist officially blacklisted was Ireene Wicker, who hosted a children’s program, Let’s Pretend. Others blacklisted early on were dancer Paul Draper and harmonica virtuoso Larry Adler when a letter-writing campaign organized by a Redhunting housewife urged the Ford Company to cancel an appearance by Draper and Adler on Ed Sullivan’s Ford-sponsored Toast of the Town. Ford didn’t cave in, but the incident so unnerved Sullivan that he cleared all future performers with the publishers of Counterattack, and Draper and Adler had to leave the United States for Europe in order to work again.

Another early blacklisted performer was the actress Jean Muir, who was fired from The Aldrich Family by its sponsor, General Foods, a few days before it made its transition from radio to television. Muir was listed as belonging to or supporting subversive organizations; one of her alleged “subversive” activities was signing a letter of congratulations to the famed Moscow Art Theater—the artistic inspiration for much of American theater—on its 50th anniversary. Philip Loeb, a regular on the long-running and highest-rated CBS series The Goldbergs, was listed and fired. When the program’s star and writer for 25 years, Gertrude Berg, protested, the program was canceled. Berg’s appeals to the presidents of CBS and NBC, William Paley and David Sarnoff, respectively, got nowhere. A few years later, barred from the industry to which he had devoted his life, Loeb committed suicide.

A Syracuse, New York, owner of supermarkets, Laurence Johnson, became a leading proponent of the blacklist, and through his status as an officer of the National Association of Supermarkets and through threats of boycotts of various products induced almost all the leading companies in the country to support the blacklist. Johnson promoted a lawyer by the name of Vincent Hartnett as an expert on Communism in broadcasting. Hartnett became a key clearance consultant; once he even refused to clear Santa Claus.

Should the FCC and federal government have acted to protect an individual’s democratic political rights, as they did at a later date with equal opportunity laws and rules that prohibited broadcast stations from discriminating on the basis of race or gender? The FCC and the rest of the government in the 1950s—like the attitudes and behavior of most of the United States, business and public alike—were being held hostage by McCarthyism. Individually and collectively, government regulators, like the average citizen, were fearful of saying, much less doing, anything that would uphold traditional American freedoms but might cost them their jobs.

The blacklist ostensibly ended in 1962 when John Henry Faulk, a star performer blacklisted by CBS in 1956, finally won his multimillion-dollar lawsuit against AWARE and Laurence Johnson. It took years, however, before an unofficial blacklist disappeared, notwithstanding the networks’ apologies for their actions. A “graylist” continued into the 1960s, and many performers, simply because they had been thrust into a position of being controversial, never worked again. CBS, despite its mea culpas, did not hire John Henry Faulk back—nor did any other network.

Why did broadcasters, networks, and stations give in to the blacklisters, and why might they well do it again? Not because they are political bigots or support totalitarian suppression of beliefs, but because the U.S. system of broadcasting is based on advertising support—and advertisers’ decisions are dictated by their profit and loss statements. Advertisers disassociate themselves from anything—program content or performers—that potential customers in the audience might find too controversial and might prompt them to react negatively to the advertiser’s message. Could a blacklist happen again? In the 1980s CBS dropped the Lou Grant show because some of its sponsors found its star, Ed Asner, to be politically controversial. Today, in the 1990s, many advertisers have withdrawn sponsorship of or demanded changes in program content that pressure groups find controversial, and networks have usually acquiesced. Even the outstanding public television station WGBH in Boston, coproducing a series for PBS in 1990 on the Korean War, changed important segments in the series following pressure from a conservative media lobbying group. Although public broadcasters are prohibited from carrying commercials, they frequently depend on corporate underwriters to fund their programs.

The Korean War, which began in 1950, offered broadcasting an opportunity to demonstrate its power to stimulate public debate and action—as broadcasting did 20 years later when it provided stark and candid coverage of the U.S. role in the war in Vietnam, quickening the public outrage that forced the United States to end its military actions in Southeast Asia. Yet in the 1950s even objective reporting was considered un-American by many. In 1950 Congress amended the Communications Act of 1934 to authorize the President to take over radio and television stations if deemed necessary for the national defense.

Political coverage otherwise began to mature on television, as it had done on radio in the previous decade. CBS established the first exclusively TV news post in Washington, D.C., assigning to it a former war correspondent and UP Moscow bureau chief, Walter Cronkite. The techniques of news reporting on TV still had a way to go, however. The networks continued to hire newsreel companies for filming their news material, and it would be a few years more before they would send out their own camera crews. News shows principally consisted of “talking heads”—that is, personalities sitting at desks and reading into the camera from scripts.

One of the political events in Washington, D.C., covered by television in 1950 and 1951 was the series of hearings of Tennessee Senator Estes Kefauver’s committee investigating organized crime. Record numbers of people in the cities where the hearings were carried were captivated day after day by the TV camera’s concentration on the hands of the star witness, Frank Costello, who objected to his face appearing on the screen. The close-ups on his hands revealed more about his feelings and attitudes than his verbal testimony did.

RALPH EDWARDS

TV HOST AND PRODUCER

A live television show that was unrehearsed, spontaneous, surprised an unsuspecting subject, and continued with nonprofessionals instead of actors presented many challenges.

The fourth year of This Is Your Life brought us a situation that the media had wondered about for all of those four years: What would you do if your subject didn’t show up? I found out—the hard way.

We had planned the “life” of Darlene Miller, a farm girl from Dubuque, Iowa, who had kept her brothers and sisters together after the death of their parents, overcoming many odds, including polio.

Airtime arrived and there was no Darlene Miller. Our spies told us that she was delayed by an accident on the Arroya Seco between Pasadena and the NBC Studios. What to do? This was “live” TV. We had to go on. We had no standby show and would not have been permitted to use a transcription in any event. We did the normal opening, and I went on stage, book in hand, and explained exactly what had happened: Our leading lady just wasn’t there! Then I continued to do the show without Darlene. I told it through her brothers and sisters, friends and relatives, extolling the virtues of older sister Darlene in holding them together. Darlene arrived 28 minutes into the show, when we were doing what we called the “future.” The subject was given merchandise, money, or other items that would help brighten life in the days to come. The show turned out well, but we were lucky because this particular story was of five children who stayed together and could be told through any one of them; however, it was a different show than we had planned—a one-of-a-kind, and once was enough for me!

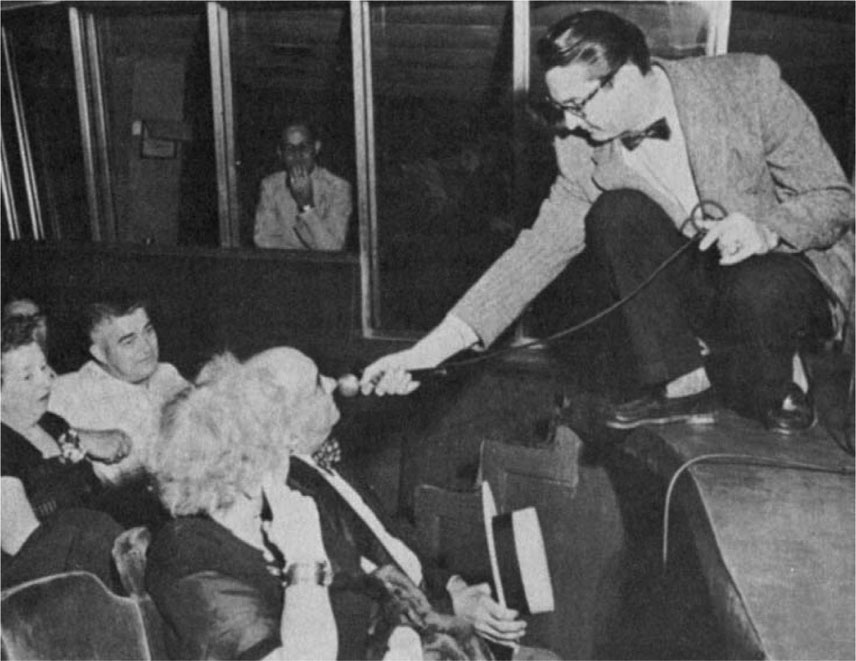

Fig 5.2 Ralph Edwards on the set of This Is Your Life.

Courtesy Ralph Edwards Productions

Other programming began to take on the feel of what TV would become—the premiere entertainment source in the country. After 15 years on radio, Your Hit Parade brought the week’s top popular songs to television. Jack Benny and Burns and Allen made the switch to television. Your Show of Shows, which set a standard for intelligent comedy and satire and starred Sid Caesar, began its run on television. The grandparent of subsequent audience participation shows, Truth or Consequences, moved from radio to television with its host of 10 years, Ralph Edwards. NBC proved that network afternoon TV could be successful with its introduction of The Kate Smith Show, and CBS followed suit a few weeks later with afternoon variety programs hosted by Garry Moore and Robert Q. Lewis. ABC’s Pulitzer Prize Playhouse was the model for future drama series that would be called the Golden Age of Television Drama. And on Christmas evening in 1950, CBS started a phenomenon that is still continuing into the first decade of the 21st century: Steve Allen hosted a format that four years later evolved into The Tonight Show and its many counterparts.

The New York pilot stations of the networks and the regional networks that received their programs were doing well. But audiences were not yet national or large enough for advertisers to put much money into local stations. A musical variety show one of the authors of this book was producing for a station in the Midwestern network in 1950 failed to go on the air at the last minute because the sponsor refused to pay an additional $25 for each script, stating that the number of people who were watching didn’t justify even that small extra cost.

There were now about 10 million television sets throughout the country. From less than 200,000 manufactured in 1947, some 140 companies produced more than 5 million sets in 1950. On the air in 64 cities were 108 TV stations, owned principally by radio licensees; 89 of these TV stations had radio stations in the same market. Though the networks and stations already on the air grew in terms of audience, the only new stations were those that already had construction permits prior to the freeze of 1948. In addition, the Korean War gave priority to the Armed Forces for electronic materials that might otherwise be used in radio and television.

STEVE ALLEN

COMEDIAN, HOST, AND WRITER

In a recently published work about The Tonight Show, written by a charming gentleman who has had long personal connection with the program, it is stated and will, sadly, now be accepted as fact by the thousands who will read the book that The Tonight Show was created by an NBC programming executive—oddly unnamed—and that its first host was Jerry Lester! Since these errors are not trivial and bear on the history of one of television’s most important and successful programs, they naturally require correction. Incidentally, it’s interesting that during the 1950s and 1960s I never had to mention the matter, for the simple reason that everyone knew the facts of the case. But new generations have now been born that never saw the original Tonight, millions who did see it have died, and a few of those who remain would appear to be suffering from what I call old-timer’s disease; so, before the record is hopelessly obscured, it needs to be reaffirmed.

The unidentified NBC executive is Sylvester “Pat” Weaver, father of actress Sigourney Weaver. Pat and I have long constituted a mutual admiration society. He was kind enough not only to put me on his network for 90 minutes a night five nights a week, but at a later stage to ask me to do a far more important prime-time weekly comedy series. For my own part, I’ve always thought that Pat was one of the best programming executives in television’s history. But it needs to be settled, once and for all, that he had nothing whatever to do with “creating The Tonight Show.” The program, as I’ve described here, had already been created, with no input from the NBC programming people, over a year before Pat had the wisdom to add it to his late-night schedule. The only change that was made was that it was no longer called The Steve Allen Show but became known as The Tonight Show —or Tonight —because the network already had initiated its still-successful morning experiment called Today.

Fig 5.3 Steve Allen hosting his radio show in 1952, a precursor to The Tonight Show.

Courtesy Steve Allen.

The FCC continued to deal with the key issue of color television. It approved the CBS system in 1950 despite its lack of compatibility; it was less expensive and was of higher picture quality than the RCA system. RCA and other manufacturers filed suit. Although a federal court upheld the FCC’s right to approve the CBS system, it delayed adoption of the system as a national standard, pending RCA’s appeal to the Supreme Court. The FCC followed suit, giving RCA additional time to perfect its system. CBS went ahead on a unilateral basis, knowing it had no guarantee of eventual adoption, and on June 25, 1951, telecast the first network color program. The Korean War, however, put the manufacture of color receivers in a nonessential category, and few CBS color sets were made. Further, the public did not want to have to scrap its personal investment in black-and-white receivers to receive the CBS color signal, even though monochrome as well as color picture quality would be improved.

The fight dragged on for a couple of years more, giving RCA time to utilize some of the previous work done by CBS, and eventually resulted in CBS joining RCA in the National Television Systems Committee (NTSC) efforts to find a suitable, compatible color system. Finally, in 1953 the FCC reversed its approval of the CBS system and okayed the new RCA system, and RCA became the principal manufacturer of color TV receivers. During CBS’s promotional period for its system, it placed receivers in a number of public areas in New York where passersby could see the quality of its color television by observing two young, attractive performers whose principal duty was to “look pretty” in color. These performers were Buff Cobb and—prior to his image as a rough, tough news interviewer—Mike Wallace.

While the NTSC was convincing the United States to accept what was considered by many an acceptable standard for broadcast television picture quality, Philo Farnsworth knew TV could be considerably better. He began experiments with highdefinition television and by the mid-1950s was demonstrating pictures with 1,100 and 1,200 lines of resolution. It would be a half century before the United States adopted a high-definition TV system.

Another early television phenomenon, pay TV, was dealt with by the FCC in 1950 as well. After several years of experiments, Zenith obtained FCC authorization to test its pay-per-view Phonevision system. Ostensibly, the system’s purpose was to provide first-run movies for subscribers who would pay a few dollars to unscramble the signal. Although a Phonevision test in Chicago was fairly successful, movie companies did not want to encourage competition from this new medium and withheld the films Phonevision needed. Further, broadcasters were concentrating on building a viable advertiser base and were not then interested in pay-per-view TV. Phonevision’s time had not yet come, but as we know now, several decades later, through cable, pay TV would begin its slow climb that could lead to eventual domination of the industry.

Fig 5.4 The technology of TV improves while receiver prices become more affordable.

Continuing its concern with monopoly in the broadcasting industry, the FCC enacted its “Rule of Sevens” in 1950. Any one owner was limited to seven TV, seven AM, and seven FM stations. An event that would affect another FCC decision a couple of years later occurred in 1950 with the formation of the Joint Committee on Educational Television, which, with the backing of FCC Commissioner Frieda Hennock, rallied support for the reservation of television channels exclusively for educational purposes.

Radio still hung in, not yet totally affected by television, inasmuch as a coast-to-coast TV network was still a year away. Ninety-five percent of U.S. homes had radios, as did half of all automobiles. Radio had 11% of all the advertising in the country in 1950, with TV at only 3%; within 15 years the ratio would be almost reversed. It was AM, not FM, that was growing: Almost 100 FM stations folded in 1950. AM licensees co-owned 80% of the FM stations. Duplication of signals by co-owned stations (FM carrying, AM originating) and a lack of inexpensive FM receivers or AM/FM sets prevented FM from being a viable advertising medium. Newspapers owned some 20% of radio stations. Although most key radio shows were making the move to television, Ed Murrow and Fred Friendly began a news documentary series on CBS radio, Hear It Now, that would raise radio journalism to new heights.

1951

One year after it began on radio, Murrow and Friendly brought their highly acclaimed documentary format of Hear It Now to television: On November 18, 1951, See It Now premiered on CBS. “Good evening,” Murrow said at the beginning of the program. “This is an old team trying to learn a new trade.” It learned it well. See It Now was willing to deal with controversy, using investigative journalism to try to right wrongs, including some of the excesses of McCarthyism as blacklisting in the industry became institutionalized. See It Now was also innovative technically. On its opening show, it became the first network program to join the East and West coasts of the United States via television, showing the Golden Gate Bridge on one monitor and the Brooklyn Bridge on another, and then together on a split screen—although two months earlier, on September 4, a group of cooperating stations and networks had inaugurated the first national hookup with a telecast of President Truman’s address in San Francisco at the conference on a peace treaty with Japan. The September 4 telecast had been seen in an estimated 95% of U.S. homes where television sets were on.

Fig 5.5 Zenith’s Phonevision promoted the idea of pay-TV in the 1950s.

Courtesy Zenith.

As television programming became increasingly attractive, movie attendance began to drop and rising numbers of movie theaters throughout the country began to close. The revenues of the major film studios suffered a one-third decline in the space of just a few years, and in 1951 more footage was being produced for television than for theatrical-release feature films. The New York Times stated: “The motion picture industry is worried, politicians are faced with learning a new art, and many a face and many a scene that formerly we merely read about or listened to we will now be privileged to look at.” This was true. Politicians soon learned that they had to become performers for the television camera if they were to influence the voters. Indeed, within three decades one actor was so successful in using the media in his role of President of the United States that he actually was elected to the office twice.

ED BLISS

FORMER EDITOR, WRITER, AND PRODUCER, CBS NEWS

I was privileged to work closely with both Edward R. Murrow and Walter Cronkite. Out of that experience it is inevitable that I compare broadcast journalism’s two giants. As night editor at CBS News and later as writer-producer for Murrow, I came to know not only a reporter of reknown but an educator. He sought through commentary and documentary to shed light on the great issues: responsibility in government, Soviet intransigence, freedom of dissent, America’s role in the world, and so forth. As a student at Washington State, Murrow majored in speech. He engaged in campus politics. He was popular. Later, in broadcasting, no one received more praise. Yet he was a shy man. Radio microphones and television cameras frightened him; they made him sweat. For most of the time, Murrow was troubled. Whatever he did, wherever we went, he carried heavy concerns: McCarthyism, the atomic bomb, the Cold War. And all the while, as he fought for social justice and understanding, he inhaled the Camel cigarettes that would kill him.

Working as a news editor with Walter Cronkite, I found a man equally devoted to the highest standards. But, unlike Murrow, he was comfortable with microphones and cameras. He could sit down before the evening news cameras after a tiring transcontinental flight and with each passing minute appear more refreshed. After his broadcast, Murrow tended to brood over the world’s problems; it was more in Cronkite’s character to meet after the program with his wife, Betsy, and go dancing. A gregarious man, in contrast to Murrow, it is difficult to conceive of Cronkite ever being shy, and he eschewed cigarettes. On the evening news, it was Eric Sevareid who did commentary. When Cronkite spoke out most strongly, as when he declared the Vietnam War unwinnable, it was not on his program but on CBS News specials. Each evening, reporting as objectively as he could, he became known as the most trusted man in America. The great common denominator for these two [giants] is their integrity. Each brought to their informing roles their absolute best, which proved to be the best there was.

Fig 5.6 Ed Bliss.

Courtesy Ed Bliss.

I Love Lucy began on television in 1951 and became the archetype for sitcoms, copied countless times but rarely equaled in popularity. Dragnet made a successful transition from radio and generated many cop-show clones. Well-known comedians, such as Red Skelton, and popular singers, such as Dinah Shore, began their own TV shows. CBS leapt in front of the other networks by bringing two of its top-rated radio soap operas to daytime television. The same year, CBS introduced its famous logo, the Eye. Perhaps the most innovative artist in television history—one who used the potential of the visual medium more creatively than anyone else—was Ernie Kovacs, who got his first network job in 1951. As exciting and farsighted as Kovacs’s work was, though, it was too far ahead of its time for broadcast executives and advertisers, and his sporadic career on network television ended with his death in an auto accident in 1962, at about the time television might have been ready to give him the superstardom it had up to then denied him.

Fig 5.7 At work in a 1950s television control room.

Courtesy WTIC.

Not only was television badly hurting movies, but it began to take an even greater toll on radio. Radio network revenues steadily declined and prime-time offerings decreased. To survive, more and more radio stations turned to deejay formats, thus presaging the reprogramming of the entire radio industry.

Captain Video and His Video Rangers

An early television hit among youngsters was this low-budget wonder, one of a number of innovative creations that materialized on the perpetually financially troubled Dumont Network. The show began in 1949, lasting until the network itself folded in 1955. It was aired live but its scripts were so short of material that good chunks of its daily 30-minute episode were filled with clips from some old B movie, usually a Western. Although no one should ever query the logic void in programming geared for children, this show stretched the boundaries of credulity. Besides the usual shortcomings with narratives dealing with alien beings (they persist in having humanoid form; hold similar values and emotions as earthlings’; often go by a single name; their leaders command an entire planet rather than nation-states), Captain Video’s aliens, with technology advanced enough for space travel at the speed of light, rely on shields and swords as their weapons, wear first-century Roman outfits, and rely on paper-written communications transported by rocket ships. And yet this pre–civil rights era show would frequently interrupt its dramatic action to air spots promoting justice, brotherhood, and tolerance of others who might not look exactly like us.

1952

On April 14, 1952, the FCC issued its now-famous Sixth Report and Order, finally resolving the matters it had begun considering in 1948 when, pending their resolution, it had imposed a freeze on applications for any new television stations. The Sixth Report and Order solved some of the problems but created others. The freeze was lifted, and hundreds of TV stations rushed to get on the air. The UHF band was established to provide for the growth of television, which otherwise would be stymied because of an insufficient number of VHF channels. At first, UHF had channels 14 through 83; however, channels 70 through 83 later would be reassigned for special and safety purposes. The FCC decided on a system of intermixture—assigning VHF and UHF channels to the same community—as opposed to deintermixture—which would have provided for only VHF or only UHF in the same market. Consequently, with UHF not having the range of VHF, its frequencies were not as desirable as those of the already established VHF stations and, coupled with the lack of UHF receivers (it wasn’t until 1962 that all sets manufactured were required to receive both VHF and UHF signals), there were few UHF viewers, very few advertisers, and even fewer network affiliations. Although UHF did grow after its initial authorization, within a few years the number of UHF stations on the air declined. In addition to making city-by-city assignments for TV channels, the FCC specified mileage separation distances for television stations in order to reduce the potential for interference.

Lifting the Freeze and Hurting UHF

UHF was the FCC’s answer, in its Sixth Report and Order, to the lack of VHF space needed to accommodate the burgeoning demand for television. But UHF was fraught with complications. Most early TV sets were not equipped to receive UHF. Consumers would either need to purchase a new set (high priced and hard to find) when most had recently bought their first, or add an external tuner and special antenna. And even then reception was problematic. Succumbing to intransigently powerful interests such as broadcast giants NBC and CBS, which had established primary affiliations with VHF stations, as well the large electronic manufacturers such as RCA, which had already tooled up to produce VHF-only sets, the commission forced UHF into a competitive disadvantage, choosing intermixture in where UHF had to compete in the same market with established VHF stations. With smaller audiences, UHF operators struggled to attract network affiliations or advertisers, causing the lack of resources needed to acquire programming to entice viewers into purchasing UHF equipment. By the end of the decade nearly half of all UHF stations had failed. It wasn’t until the passage of the All-Channel Receiver Act that required built-in UHF tuners on all new sets that the band began to recover. However, it took another 20 years before UHF became truly viable, thanks to the spread of cable that made UHF as easy to receive as VHF.

Educators won their fight. Of the 2,053 channels assigned to 1,291 communities in the Sixth Report and Order, 242 were reserved for educational stations. FM advocates lost their fight. The FCC assigned the more desirable audio frequencies for TV sound transmission, leaving FM where it was, with frequencies that FM’s founder, Edwin Armstrong, believed were inadequate for the effective growth and full service of the medium.

As the politics within broadcasting accelerated, so did the political use of broadcasting. In his successful run for President against Adlai E. Stevenson in 1952, Dwight D. Eisenhower and his campaign managers made the first large-scale use of political ads on television. A series of 20-second spots concentrated on personalities rather than issues, much like the campaigns of the 1980s and 1990s more often than not concentrated on “sound bites” rather than substance. Eisenhower’s running mate, Richard Nixon, charged with the misuse of campaign funds, his political career at the edge of a precipice, used television to convince the public, in his famous “Checkers” speech, that he was not a crook by shifting the charges into a discussion of the gift of a puppy that his daughter had named Checkers and that he vowed to keep. Nixon was eloquent in his use of the medium and remained on the Republican ticket, ensuring his political future. Joseph McCarthy also used television to his advantage, convincing the public of the dangers of international Communism, against which he was self-anointed to lead the fight.

While I Love Lucy shot to the top of the ratings charts in its second season, setting off a deluge of half-hour copycat sitcoms, programming centering on two wars and a frightening prophecy of what a future one would be like also attracted large numbers of TV viewers. Victory at Sea, a 26-episode documentary of the naval battles of World War II, with background music by Richard Rodgers, began on NBC and became one of the most popular and oft-repeated series in television history. Ed Murrow, one of the few reporters who attempted to bring the events and issues of the Korean War into U.S. living rooms, worked with Fred Friendly to produce a number of programs from Korea for See It Now. Among these offerings were the acclaimed “Christmas in Korea” shows in 1952 and 1953, programs that were especially courageous in the McCarthy era because they tried to be objective, show the truth about some of the horrors of war, and avoid phony patriotism and the exploitation of the country’s Communist phobia. In addition, for an indication of what future wars might be like, the public saw on TV an atom bomb test in the Nevada desert.

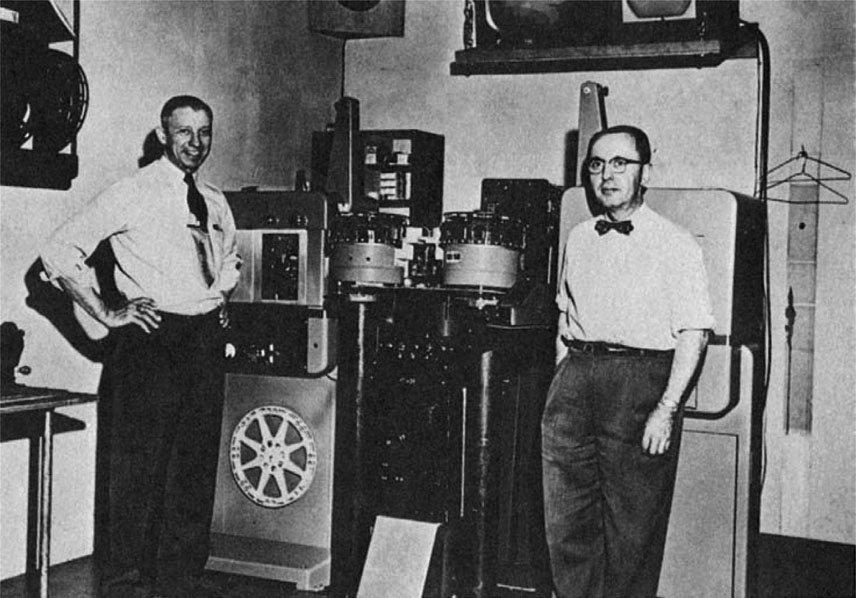

Fig 5.8 The television equipment in this 1950s photo includes revolving slide drums, center, and larger movie projectors on each side. Images from all of these sources were multiplexed by means of movable mirrors into a single film-chain camera.

Courtesy David Richardson.

Culture and religion entered television with a bang in 1952. The DuMont network put Bishop Fulton J. Sheen, a dynamic speaker, in a program without commercials entitled Life Is Worth Living, pitting this offering against Milton Berle. Although he did not displace Berle, Sheen stayed on the air for many years with respectable ratings. CBS took a chance with Omnibus, hosted by Alistair Cooke, which had been tried and dropped by other networks. It featured plays, poetry readings, documentaries, and even lessons in classical music by Leonard Bernstein. It did better than expected during the several years it remained on TV. NBC started a trend with the first Today Show, with Dave Garroway, one of the many stars who started in TV in Chicago. That same year, what was to be the longest-running daytime variety show on television, Art Linkletter’s House Party, began on CBS.

RAY SCHERER

FORMER NBC WHITE HOUSE CORRESPONDENT (TRUMAN, EISENHOWER, KENNEDY, AND JOHNSON ADMINISTRATIONS)

When I started covering the White House for NBC, Harry Truman was President and radio was king. Television was little more than a gleam in General Sarnoff’s eye. Network correspondents were not permitted to broadcast from inside the White House. They had to rush back to their studios in downtown Washington when news breaks came. Radio news on the hour was a long way away.

Broadcasting possibilities improved with the arrival of President Eisenhower and his news secretary, Jim Hagerty. Hagerty was open to new ideas. We began taping Ike’s news conferences for radio and, in January 1955, filming them for television.

A breakthrough of sorts occurred when Hagerty gave NBC permission to do radio spots from inside the White House. The pressroom off the West Wing lobby was unsuitable. It was the province of the writing press and there were too many extraneous noises, including the slap of playing cards.

Where to set up a microphone and broadcast equipment? I convinced Hagerty I could do it from the phone booth behind the guard’s desk in the lobby. I broadcast from there for about a week, my engineer perched over me like a giant praying mantis. I felt myself coming down with galloping claustrophobia and had my engineer set up the NBC radio mike in the photographer’s film-changing room, a dingy cubicle just outside Hagerty’s office.

It was hardly studio quality but it worked. I was the first to do a daily news program from the White House. In Kennedy’s time the networks were given broadcast booths inside the pressroom, but by then TV was the big player and radio no longer claimed priority. By the Carter era, a White House TV reporter could get on the air within seconds, and in the 1980s with Reagan, the television President, the pressroom was turned into a television studio. Broadcasting had moved from the back row to the front row, but it took 40 years.

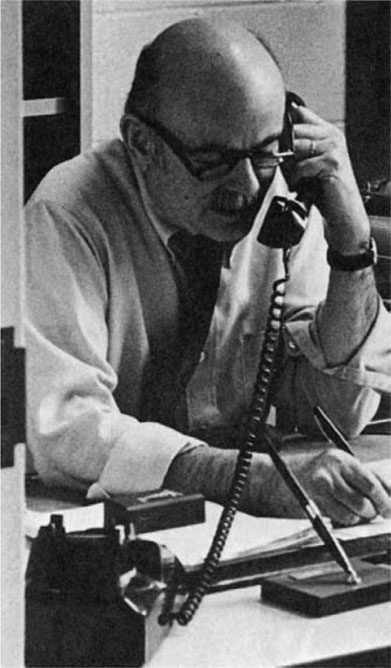

Fig 5.9 Ray Scherer.

Courtesy Ray Scherer.

If you can’t beat ’em, own ’em, and newspapers did just that, owning, in 1952, 45% of the country’s television stations. Although the civil rights movement of the 1960s was almost a decade away, advertisers began to recognize the buying power of blacks in many parts of the country, and a number of radio “Negro stations,” as they were called, went on the air, orienting programming and advertising to black audiences. Almost all of these stations were owned by whites.

1953

Anyone old enough to have watched television in 1953 will tell you they remember Lucy having a baby right on the air. In fact, she did; the I Love Lucy show decided to follow, on the sitcom, her real-life pregnancy through to the birth. Seventy percent of all television homes and 92% of sets in use that evening were tuned to the birthing episode. The first issue of TV Guide came out on April 3, 1953, and its cover featured a picture of Lucy’s son, Desi Arnaz, Jr.

TV spectaculars—heavily promoted specials with many stars and usually an hour or more in length—came into being with the production of The Ford Fiftieth Anniversary Show. The radio documentary series You Are There, developed by Robert Lewis Shayon years before for CBS radio, came to television, with Walter Cronkite serving as anchor in the simulated re-creation of historical news events. Adults and children alike were attracted to a new series right out of the comic pages, The Adventures of Superman. ABC brought major league baseball to television on a regular basis with the Saturday afternoon “game of the week,” and DuMont brought professional football to prime-time television with Saturday night games. In addition to See It Now, Murrow and Friendly began a weekly Person to Person series that interviewed famous people, live, in their homes—a format copied many times since and honed to a fine point by Barbara Walters in the 1980s and 1990s. Pioneering the path for Walters and other women who would become prominent TV newspersons was Pauline Frederick, the first woman to become a full-fledged correspondent when she was hired by ABC in 1948. In 1953 Frederick moved to NBC, where she gained worldwide attention as a United Nations correspondent for the next 21 years.

Although anthology drama became a staple of television in the late 1940s, it wasn’t until 1953 that the seminal play of the Golden Age of Television Drama, according to many critics, went on the air. The Philco Playhouse production of Marty, by writer Paddy Chayefsky, established the sensitive, realistic, in-depth, slice-of-life format that was to dominate anthology drama series such as Goodyear Playhouse, Robert Montgomery Presents, Studio One, U.S. Steel Hour, and Kraft Television Theater for years to come.

BETTY FURNESS

THE LATE BETTY FURNESS WAS ONE OF TELEVISION’S EARLY COMMERCIAL STARS

Those of us who worked in very early TV didn’t know we were pioneers. We were just trying to earn a living. For the first few years [payment of] $25 a show was quite acceptable.

While I did some isolated shows at CBS, my first regularly scheduled program was Fashions Coming and Becoming at DuMont in 1945. It was 15 minutes once a week and that was quite often enough. The studio was in an office building on Madison Avenue. It was, in fact, a converted office with the required very hot lights hung from the ceiling. Very hot meant that we had to dress like firemen for rehearsal, heads covered, dark glasses. The heat was almost unendurable. One day I laid a thermometer on a table. The temperature was 130 in five minutes. I wore combs with a metal edge in my hair at the time and burned my hand touching one. The program went off the air in the summer because of the outdoor heat!

In 1949 I played a small part on a new one-hour drama called Studio One at CBS. Westinghouse had just started sponsoring the show, and the ad agency asked if I’d like to try [doing] the commercials the next week. $100. Sure I would. That started an 11-year job that made me rich and famous.

Studio One was live, like all shows at the time. I worked in a kitchen set in the same studio as the drama. Commercials, which now run from 10 to 30 seconds generally, were a minute and a half to three minutes. Everyone had to come out on time … the drama and the commercials. The teleprompter had not been invented and I wasn’t comfortable using cue cards; I wanted to look into the eye of the camera, therefore, the eye of the viewer. So I memorized one three-minute and two minute-and-a-half commercials each week. Once I opened my mouth, there was no way out. I had to know [the lines] and say them correctly and promptly. It was quite stimulating.

In 1952, Westinghouse bought the TV coverage of the political conventions of both parties on CBS. The teleprompter had been invented, which was nice because I had a cycle of 96 commercials. Again I worked along with the “live” show in a studio adjacent to CBS News in the convention hall. I logged more air time than any speaker of either party, and because an enormous number of people had bought TV sets just to watch the first televised conventions, I became famous.

For those of us who started early, TV was never as much fun (or as terrifying) when everything was filmed or later taped and edited. It was too “safe.”

I’m sometimes asked today if I miss live TV. Actually, because I’m a consumer reporter on a news program, part of what I do is still live, with the lifesaver of a smoothly operating teleprompter. We in news are still looking right in the eye of the viewer.

Fig 5.10 Betty Furness.

Courtesy Betty Furness.

A new generation of playwrights was spawned by television. One of the authors of this book, as a young writer in the early 1950s, remembers a script competition for a first prize of $1,000 (a large sum then) offered by TV station WTVN in Cincinnati. When the results were announced in early 1953, this writer was pleased to learn that his entry was good enough to be awarded honorable mention status. But he was especially impressed with the obvious talents of another young, unknown playwright, who won two of the top awards, including first prize. That writer’s name was Rod Serling.

Fig 5.11 As network radio declined in the early 1950s, local stations became more involved with program origination. Here Allen Ludden hosts a youth-oriented panel show.

Courtesy WTIC.

The NBC and CBS networks began 15-minute evening news shows. The Academy Awards were televised for the first time. A dramatic TV event occurred on the highly popular Arthur Godfrey and His Friends show, disillusioning many of Godfrey’s fans. He fired, on the air, singer Julius La Rosa, a regular on the program. After La Rosa finished a song, Godfrey said to the startled singer and national audience, “That, folks, was Julie’s swan song.”

By 1953, 45% of U.S. homes had television. The number of stations on the air almost tripled from the year before, to 365. Advertising income increased by more than 35%. Network profits shot up at NBC and ABC. But ABC wasn’t competing so well, and it merged with Paramount Pictures to provide greater resources for competitive programming. Most significant was the serious—and self-protective—entry of filmdom into television.

As a result of the Sixth Report and Order, the first noncommercial television station went on the air in 1953: KUHT at the University of Houston in Texas. Also in 1953 the FCC, as noted earlier, finally authorized color television, reversing its position on CBS and approving RCA’s compatible system. Before the year ended, the first compatible color sets, made by Admiral, were being sold for $1,175, a price not too many people could afford, considering it represented more than half a year’s salary for many individuals.

Meanwhile Senator McCarthy’s power was growing, and he threatened both the VOA and the FCC, seeing to it that they hired people he designated as loyal and fired those he called subversive. Concomitantly, the organization that was to take the lead in blacklisting in the broadcast industry, AWARE, Inc., was formed. Though broadcast executives cooperated fully with the blacklist, they weren’t entirely insensitive to its effects. When it was revealed that Lucille Ball had once been a member of the Communist Party, CBS’s head, William Paley, made certain that she was quickly cleared. How could America’s favorite housewife be a Communist? Moreover, without her as star, the top-rated I Love Lucy show would stop making money for CBS.

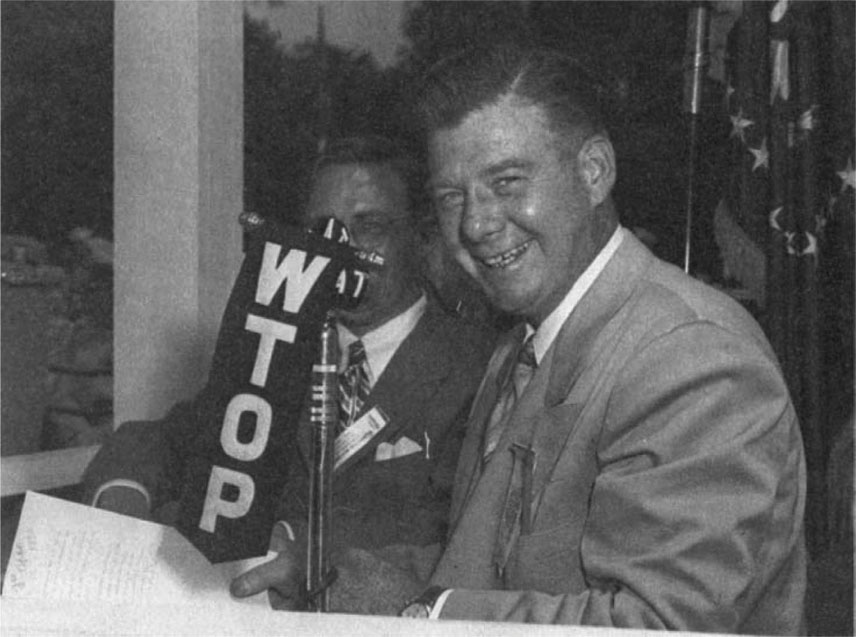

Fig 5.12 Arthur Godfrey kept audiences tuned to his radio (later, also television) shows throughout the 1940s and 1950s.

Courtesy Artist’s Proof, Alexandria, Virginia.

Fig 5.13 A transition in recording techniques took place in the 1950s as disk recording made way for the tape recorder.

Courtesy WTIC.

What about radio? In 1948 a person listened to the radio an average of 4.4 hours a day; in 1953 that figure was down to 2.7 hours. News and music replaced the entertainment that had once dominated prime-time radio and had now moved to television. In 1948 radio prime time had 14% news and public affairs programs; in 1953, it had 40%.

1954

Although broadcasting capitulated to McCarthyism, broadcasting was also the key factor in McCarthy’s ultimate demise. Three 1954 events revealed in close-up the senator’s true nature. One was the Army–McCarthy hearings, in which McCarthy initiated an investigation of the U.S. Army on the grounds that it, too, had been infiltrated by Communist subversives. The others were Ed Murrow and Fred Friendly’s two programs on McCarthy, one delineating McCarthy in his own recorded words and actions and the other giving McCarthy the opportunity to respond. These programs highlighted television’s ability to get behind the facade and show “warts and all” and to affect the course of public affairs—when it wanted to.

During 1953 Murrow and Friendly’s See It Now had gathered as much material as it could about McCarthy, to let the nation see the senator without the “Emperor’s Clothes” protection the media had given him. Finally, after a cool reception from CBS management, the show was allowed to air on March 9, 1954. But CBS virtually washed its hands of it and refused to promote it, and Murrow and Friendly paid for their own advertisement for the program in The New York Times. At the end of the program showing McCarthy simply being McCarthy, Murrow added one of the few bits of commentary in the show, warning that this was no time for people who opposed McCarthy’s methods to keep silent:

As a nation we have come into our full inheritance at a tender age. We proclaim ourselves, as indeed we are, the defenders of freedom, what’s left of it. But we cannot defend freedom abroad by deserting it at home. The actions of the junior Senator from Wisconsin have caused alarm and dismay among our allies abroad and given considerable comfort to our enemies. And whose fault is that? Not really his. He didn’t create this situation of fear. He merely exploited it, and rather successfully. Cassius was right: “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves.”

On April 6, McCarthy was given a full half-hour of See It Now to respond. His vicious, clearly paranoid attack on Murrow as “the leader and the cleverest of the jackal pack which is always found at the throat of anyone who dares to expose individual Communists and traitors” was too much even for many of the viewers who until then had enthusiastically supported McCarthy’s witch hunts. For the first time, mainstream America was beginning to question McCarthy’s motives and stability.

The Army–McCarthy hearings began on April 22, and the glaring eye of television, given a bit of courage by Murrow and Friendly, did not now run away from the truth. ABC carried the hearings for their entire 187 hours over 36 days; NBC carried the proceedings live for two days and then switched to evening summaries; and CBS carried a 45-minute daily summary. As Life magazine stated, “Politicians, lawyers, and witnesses soon became as recognizable as movie stars.” McCarthy’s irresponsible, badgering, bizarre behavior during the hearings raised further questions in the minds of middle America about his methods and fitness to serve. As the premiere broadcast historian Erik Barnouw has written, “A whole nation watched him in murderous close-up—and recoiled.”

Fig 5.14 This early photo anticipated radio’s aggressively promoted “mobility” image in the age of television.

Courtesy Westinghouse.

Before the end of 1954, two-thirds of the Senate voted to censure Senator McCarthy.

Murrow, because of the McCarthy programs, was now controversial, and CBS’s head, William Paley, realized that the controversy was rubbing off on the network. See It Now was soon relegated to a less favorable time slot, a year later was changed from a weekly program to an occasional special (See It Now and Then, some Paley detractors called it), and eventually was forced off the air altogether.

The blacklisting continued. Censorship invaded the anthology drama, and more than one author took his or her name off the credits upon finding that the script had been changed to avoid anything controversial, particularly civil rights or civil liberties implications that much of America equated with Communist subversion. Nonpolitical, innocuous programming was preferred by networks and advertisers alike. The Miss America Pageant made it to television. Dragnet, You Bet Your Life, The Jackie Gleason Show (which spawned The Honeymooners), Bob Hope, and Walt Disney’s Davy Crockett (which prompted a nationwide fad for coonskin hats) joined Lucy as the nation’s favorite TV shows. At the same time, several anthology drama shows, such as Studio One, Philco-Goodyear Television Playhouse, and Kraft Television Theater, finished consistently in the top 10 in the rating charts. One auspicious debut was NBC’s The Tonight Show, hosted by Steve Allen, which replaced an earlier version, Broadway Open House with comedian Jerry Lester. The Tonight Show, still going strong in the 2000s, would be hosted subsequently by Jack Paar, Johnny Carson, Jay Leno, and Conan O’Brien.

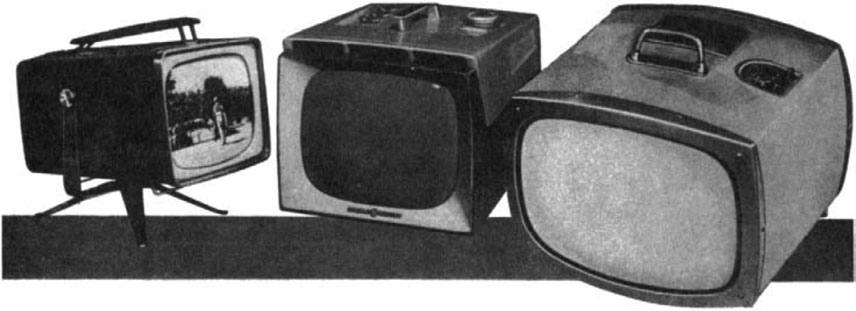

The public bought more and more sets. More than 30 million homes had television, compared with half that number just three years earlier—still only 27% of the population, but quickly growing. Prices of sets had fallen more than 50% in that time, averaging about $175 in 1954. More and more people watching TV in the early evening hours found it a distraction to have to make dinner, motivating a clever manufacturer to come out with a financial bonanza in 1954, the TV dinner. Although both NBC and CBS were broadcasting some programs in color, there were still very few color sets in use—the number was estimated at not more than 10,000.

The networks and advertisers were ecstatic about TV as a whole. More than $800 million was spent on television commercials in 1954. Because most programs had only one sponsor, advertisers, through their advertising agencies, had virtually total control over television programming, not only approving of scripts and performers but sometimes supervising production values and censoring dialogue and ideas as they wished.

Even in the noncivilian area, television grew; the Armed Forces Radio Service became the Armed Forces Radio and Television Service.

Fig 5.15 To offset the effects of television, radio promoted mobility and intimacy. The prevailing slogan of the day: “Radio—your constant companion.”

The year 1954 was the end of the line for Edwin Armstrong. He was depressed by what he felt was the FCC’s destruction of FM’s potential by its 1952 Sixth Report and Order assigning the best audio frequencies to TV instead of FM. After six years of his patent-infringement lawsuit against RCA and NBC, fighting the superior legal resources of his former friend David Sarnoff, who claimed that RCA and not Armstrong had been the principal developer of FM, Armstrong was physically and emotionally exhausted and almost bankrupt. He committed suicide by jumping out of the window of his 13th-floor Manhattan apartment, not living to see the subsequent growth of FM that enabled it to surpass AM and to reach its present dominant position.

Radio continued to change in order to survive, with basically only the soaps remaining as the audio medium’s principal form of nonmusic entertainment. Localization, narrower demographics, local advertising, and the Top 40 music format seemed to be the answer for survival.

1955

While some of the rest of the United States in 1955 was beginning to question its devotion to McCarthyism as a result of the See It Now programs, the Army–McCarthy hearings, and the Senate censure vote, broadcasting didn’t waver and held tight to its blacklist. Broadcast executives decided it was more important not to lose advertisers’ dollars than to act on any personal or ethical beliefs in democracy they may have had. The business of broadcasting went on as usual.

Fig 5.16 Symbolic of the new video age was this futuristic Philco “Predicta,” which graced the modern 1950s living room.

The number of television sets manufactured continued to grow, reaching a total of 46 million, with 64% of America’s households estimated to have TV sets. One factor for the increasing sales—almost 8 million in 1955—was the continuing drop in price: The average cost of a set was now $160. Although more and more programs were in color, only 20,000 color TV sets were purchased that year. A new video distribution system designed to bring TV stations to communities too isolated to receive a usable off-the-air signal showed signs of growth, too. Having begun in 1949 in rural Pennsylvania and Oregon, community antenna television (CATV) now served 150,000 households in 400 communities—only 0.5% of U.S. households but a foot in the door for what we now call cable television.

Fig 5.17 Local TV stations expanded in-house programming efforts during the 1950s, and giveaway shows were among the most popular.

Courtesy Patricia McKenna.

Ninety-six percent of the country’s homes had radio sets, as did 60% of its automobiles. But only 4% of the sets were FM. The number of stations grew, too: 2,732 commercial AM, 540 commercial FM, 124 noncommercial educational FM, 458 commercial TV, and 12 noncommercial educational TV stations were on the air in 1955. While most of the economy was growing, however, radio was suffering. From billings that accounted for 11% of all advertising in the country in 1950, radio dropped to 6% in 1955 (from more than $600 million to less than $550 million); during the same period television’s share rose from 3% to 11% (from only $171 million to more than $1.5 billion).

The expanding economy was reflected in programs. In the 1930s a popular audience participation quiz show was The $64 Question, in which a contestant could double the amount of money won by answering each subsequent question correctly, to a total of $64. A television version of that program, which became one of the most popular TV shows in America, made its debut in 1955, but now it was The $64,000 Question. At the other end of the programming scale, NBC’s color telecast of Peter Pan, starring Mary Martin, was seen by an estimated 65 million viewers, the largest audience for a TV program up to that time. At the other side of the continent—New York was the center of television production—the first major movie studio decided to join rather than fight the television competition, and Warner Brothers broke the general ban on offering movies to TV by making TV series based on some of its famous films.

Programming breakthroughs were too late to help the DuMont network, however, the resources of which were simply not enough to compete with NBC and CBS, and in 1955 it folded. ABC barely survived. Radio tried to survive on whatever new approaches it could find. One such approach came to the fore in 1955, although few in radio would guess its ultimate impact. A recording by a pop music group called Bill Haley and His Comets became the number-one radio play. The song, called “Rock Around the Clock,” ushered in the era of rock music on radio and, with it, a new audience that would prove to be radio’s economic salvation. Around this time two radio programming innovators, Todd Storz and Bill Stewart, introduced the Top 40 format in Omaha, Nebraska. This would mark the intensification of the long and intimate relationship (some would call it a marriage) between the radio medium and the recording industry, as both relied on each other for their well-being and continued prosperity. The recording industry manufactured the popular, youth-oriented music radio wanted and needed, and the latter provided the exposure that created a market for this product. From the perspective of the recording industry, radio was the perfect promotional vehicle for showcasing its established, as well as up-and-coming, artists. FM radio, struggling to remain afloat, used a different kind of music to bring in some money. The FCC’s Subsidiary Communications Authorization (SCA) permitted FM to use its subcarrier to transmit so-called “elevator” (and other kinds of) music to dentist’s offices, supermarkets, waiting rooms, and, of course, elevators.

A national event that was to catapult television into a political and social change agent occurred in 1955. On the heels of the 1954 Supreme Court Brown v. Board of Education decision that ruled “separate but equal” educational facilities unconstitutional and called for integration of the nation’s schools, Rosa Parks’s arrest for refusing to sit in the segregated section of a Montgomery, Alabama, bus led to a city-wide bus boycott and was a key factor in the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr.’s, ability to rally concerned citizens for nonviolent civil rights actions. At first the media ignored King, but by the end of the following year they had made him nationally known. Moreover, TV eventually played an important role in showing the public at large the brutality of segregationist practices and helped change people’s attitudes into supporting equal rights for all Americans. Another event occurred in 1955 that years later would become the basis for a further example of TV’s power to affect public opinion in extraordinary ways: The first U.S. military advisers were sent to Vietnam.

Despite the dynamic events in the rapid evolution of television, the medium’s fourth network, DuMont, finally ceased operations due to growing debt and insur-mountable competition from what would become known as the Big Three nerworks.

Fig 5.18 The Broadcast Education Association (BEA) was formed in 1955 as an academic organization devoted to communications. The BEA’s founders recognized the importance of close interaction with members of the professional broadcast community.

Courtesy Broadcast Education Association.

1956

Two rather diverse happenings in 1956 changed the course of broadcasting. On April 15, at the annual convention of the NAB, the Ampex Corporation introduced the videotape recorder (VTR), using 3M tape. Within weeks, backorders for the VTR and tape were piling up. Though not yet utilizing electronic editing, the VTR changed the process of television broadcasting, including rehearsal and performance schedules and time, studio use, and location shooting, and eventually put an end to the live show. (Although Bing Crosby Enterprises had demonstrated a videotape machine in 1952, it was not refined enough to go into production.)

The other event involved John Henry Faulk, a rising star at CBS who at the time was a vice president of the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (AFTRA), the broadcast performers’ union that took a public stand against the black-list. AWARE, in an effort to discredit and silence AFTRA opposition, tried to pressure AFTRA members to name names and included Faulk on its list of subversives. Faulk sued. As noted earlier, Faulk eventually won, in 1962, but his principles and courage cost him his career.

Having given tacit support to McCarthyism and blacklisting, President Dwight D. Eisenhower understood the power of television. Running for a second term against Adlai E. Stevenson, Eisenhower tried an innovative campaign approach. His campaign organization bought the final five minutes of time on popular half-hour TV shows—the regular sponsor paying for the first 25 minutes—and presented appeals to an already watching audience.

Fig 5.19 Weather becomes a popular feature on TV.

Courtesy David Sarnoff Library.

More big-money quiz shows followed on the heels of the popularity of CBS’s The $64,000 Question, including an ante-raising NBC program, The $100,000 Big Surprise. CBS countered with The $64,000 Challenge, on which winners on The $64,000 Question would vie for even larger prizes; one contestant won $264,000.

Fig 5.20 The look of portable TVs in 1956.

A new genre came to television, one that would ride the video range for two decades. Cheyenne, Gunsmoke, and The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp made their debuts in 1956, and their successes spawned a plethora of Westerns that would dominate prime-time programming.

Another kind of legend-to-be also made a television debut in 1956; Elvis Presley’s appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show got the kind of national exposure that guaranteed an idolization few other entertainers would experience.

All was not frivolity, however. One of the most successful of high-quality drama programs, Playhouse 90, began its four-year run. Perhaps the highest-quality children’s program ever to be seen on commercial television, Captain Kangaroo began its 30-year TV history. NBC experimented with something new in news: two news anchors instead of one, with the Huntley-Brinkley Report and its tag line, “Good night, Chet,” “Good night, David,” becoming a household saying throughout the nation for many years.

1957

Although Senator Joseph McCarthy died in 1957, McCarthyism lived on. It continued to abuse the constitutional rights of many media personnel. Any reporter who deviated from the government party line became a persona non grata. In one of the most famous cases, the government was unhappy with CBS correspondent William Worthy’s traveling to off-limits China and reporting from Peking, so the State Department took away his passport.

Some programming innovations succeeded, such as Dick Clark’s American Bandstand, destined to be a TV staple for several decades. But others were too far ahead of their time. Nat King Cole was the first black performer to host his or her own show. Despite impressive responses from viewers and critics, racist attitudes resulted in no sponsorship and the program lasted only one season. Some types of programs became instant fads. Quiz shows challenged the popularity of Westerns, in 1957 accounting for 37 hours of network programming each week. But rumors of possible quiz show fixes began to circulate through the television industry, even as hints of payola (record companies bribing disc jockeys to play certain songs to make them bestsellers) made the rounds of the radio industry.

The price of color sets began to go down, the number of TV programs in color began to go up, and NBC introduced its new symbol of color, the famous Peacock.

Fig 5.21 Children’s TV programming came into its own in the 1950s.

Courtesy David Richardson.

1958

The big news in broadcasting in 1958 was the quiz show scandals. They broke with the assertion by a contestant on Twenty-One, a high-suspense competition in which participants answered questions from soundproofed glass isolation booths, that another competitor had been given answers in advance to beat him. The disgruntled contestant claimed that the producers had coached him and given him answers to be the long-running champion, and he felt he’d been double-crossed. Further revelations followed concerning this and other quiz shows, such as The $64,000 Question. A grand jury investigation commenced, and New York newspapers began to dig into the allegations. Before the year was out, several tainted quiz shows went off the air.

The scandals commanded national attention through 1958 and 1959, with millions of viewers feeling duped. In Washington, Congress convened a Special Committee on Legislative Oversight to hold hearings on the exposures. Quiz shows all but disappeared from the air, and it was some years before the public again believed that any of them were legitimate. The attractiveness of their format, however, remained, and in this last decade of the broadcast century audience participation shows are the highest-rated syndicated programs on television.

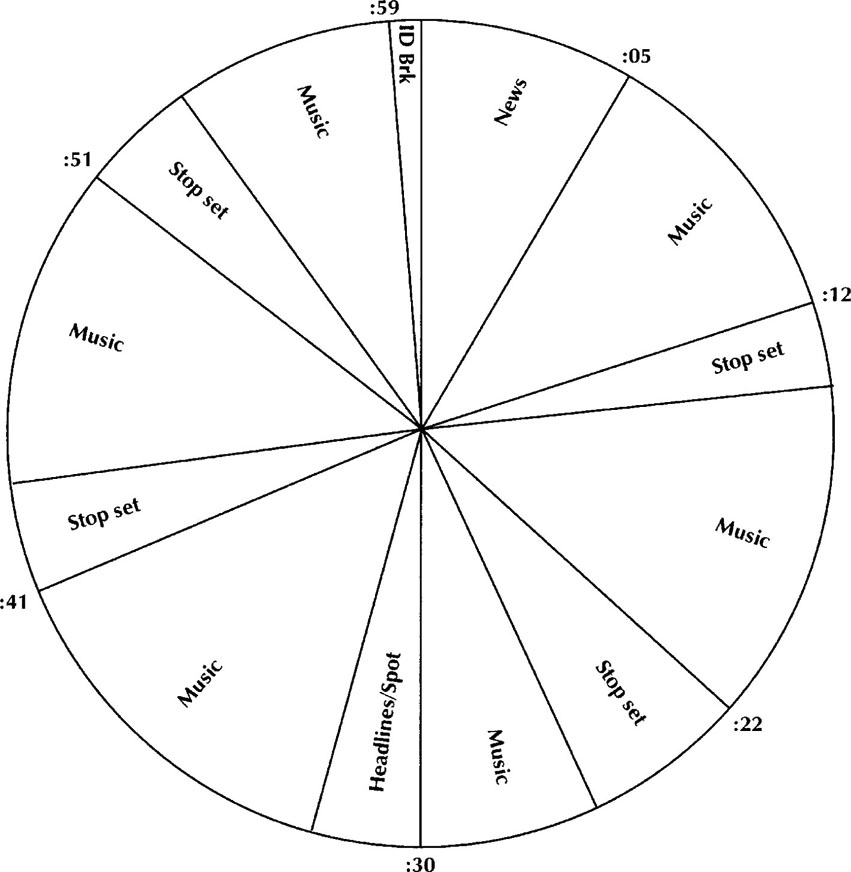

Fig 5.22 The practice of program formatting took hold in the 1950s. Radio program clocks were implemented to keep things on their prescribed course.

KIRK BROWNING4FORMER DIRECTOR

NBC SYMPHONY CONCERTS

I got to be director of the NBC Symphony concerts with Toscanini in 1950. They had a sports director doing them because it was a remote, out of studio, in Carnegie Hall. He’d read on the program that one of the selections was going to be The Girl with the Flaxen Hair, by Debussy. At the time I was working with Samuel Chotzinoff, the musical director for the National Broadcasting Company. I don’t think I was any more than an assistant director at the time, but anyhow, I was watching the program on a monitor at Carnegie Hall with Chotzy as it was going on live. I’m looking at a picture of the maestro, Toscanini, conducting, and all of a sudden, supered over the maestro’s face, is this picture of a girl sitting in front of a mirrored lily pond combing her hair with a brush. Chotzy turned to me and said, “Kirk, from here on, you’re directing the Toscanini shows. I don’t care what you do with the picture—just never be on anything but Toscanini.” So that’s how I started doing the NBC Symphony.

Fig 5.23 Kirk Browning directing a taping of a 1960s television program.

Courtesy Kirk Browning.

The regulators as well as the regulated were not immune from scandal. Charges of bribery resulted in the resignation of FCC Commissioner Richard A. Mack.

Other than this unwelcome notoriety, the business of broadcasting continued as usual, television growing and radio slowly adapting to new music formats geared to narrow demographics. The TV networks were at their peaks, drawing 95% of primetime audiences for the programs. See It Now, despite—or perhaps because of—its contributions to social and political justice and progress, was still controversial, and CBS’s William Paley, after allowing it occasional specials during the previous few years, now took it off the air entirely. United Press and International News Service, both competing poorly against the Associated Press, merged into United Press International (UPI). Although cable continued to expand, few took it seriously, and the FCC decided that because cable was not broadcasting, the FCC did not have the authority to regulate it. It would not be until a dozen years had passed, when cable more clearly posed a threat to broadcasting, that the FCC would change its mind.

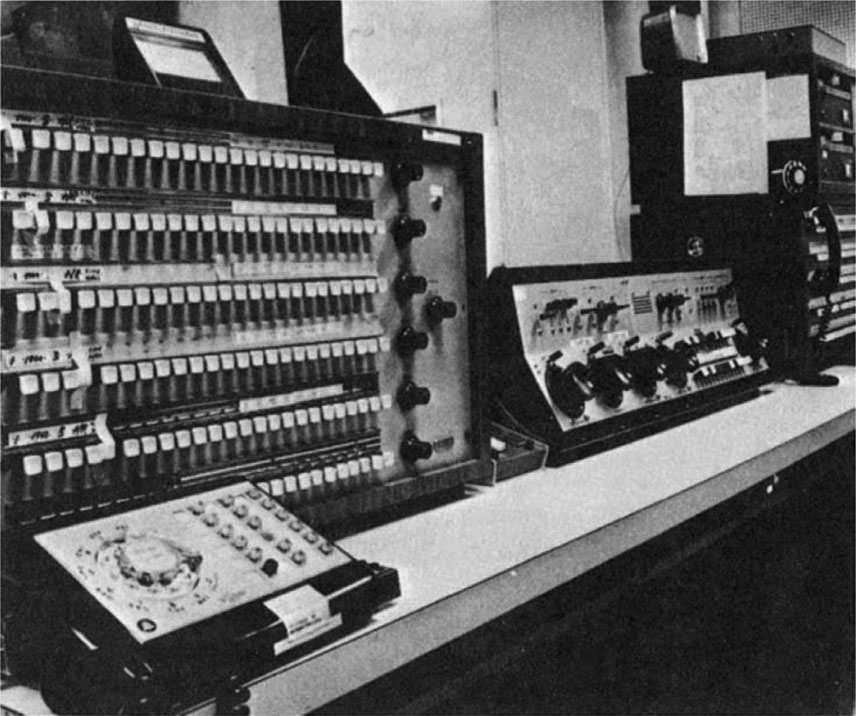

Fig 5.24 Network automation and routing control area in the late 1950s.

Courtesy WABC, New York.

1959

Networks in 1959 tried to refurbish their images tarnished by the quiz show scandals by putting more money into their budgets for public affairs programs. The FCC called for more public service programs. These factors resulted in a quick rehabilitation of Ed Murrow and Fred Friendly at CBS, who began CBS Reports, a documentary series that would make at least as many waves as See It Now had. Networks played up their news coverage, including extensive reporting of the cross-country visit to the United States of Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet premier. Vice President Nixon, campaigning for the 1960 Republican Presidential nomination, got a boost from television when his “kitchen debate” with Khrushchev (literally taking place in an exhibition kitchen at a trade fair in Moscow) was widely covered by TV in the United States.

Fig 5.25 Technician at work on a communications satellite (COMSAT) in 1958.

LYNN CHRISTIAN

BROADCAST EXECUTIVE AND FM PIONEER

A group of background music operators, who used their FM subcarriers for cost-

saving delivery to save telephone line costs, gathered in the attic of the Palmer House Hotel in January 1959 to discuss changing the FM Development Committee into an FM broadcasting association. This band of parttime radio people—the main channel was only being programmed less than 12 hours a day in most cities—knew the potential of high-fidelity radio and perceived the possibilities of marketing stereo.

The National Association of FM Broadcasters [NAFMB] was founded at this meeting and met prior to the opening ceremony of the annual NAB convention each Spring (usually in Chicago at the Conrad Hilton Hotel). This initial band of independent FM “turks” grew and eventually held their own convention. In the early 1970s the group became the National Radio Broadcasters Association [NRBA] and with nearly 2,000 members merged with the National Association of Broadcasters in 1984. The lobbying of the NAFMB and NRBA allowed much of the FM explosion and creative experimentation in programming, promotion, and marketing in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

Prior to 1965, most of the FM dial was classical, esoteric, or beautiful music. There was very little talk, news, or sports on FM. The general public bought FM radios during the 1950s and 1960s because they liked the nonmainstream programming (very little pop-rock music), high-fidelity (stereo) sound, and low deejay presence; many assumed FM was a noncommercial band. Because so little commercial time was sold in the early years and because of the limited placement of low-key (nonjingle) spots, listeners made this erroneous assumption. Most listener surveys in the 1960s indicated that the primary reason people tuned to FM was the lack of both talk and commercials. In the late 1970s and 1980s this changed. In the mid-1960s, I led a national campaign for the NAFMB and the FM industry to convince Detroit to install FM radios in cars and trucks. Over 1,000 FM stations aired a free, one-year spot campaign to encourage listeners to ask for AM/FM car radios when they purchased a new car.

The pressure created by this major promotion was very effective in a couple of ways. First, it motivated General Motors and its Delco Division and Ford Motor Company and its Philco Radio Division to accelerate their plans. It also demonstrated FM radio’s power to sell the consumer a new product. It was one of the first national FM spot campaigns and FM’s first great success story. Happily, in 1969 I was awarded an Armstrong Foundation Award for this effort, as was David Polinger, who managed WTFM in New York. Initially, the NAB in Washington and state broadcasters’ associations—dominated by the AM business folk—resisted the growth of FM. After the commission forced changes and broadcasters witnessed the development of new profit centers in their companies, they jumped on the FM bandwagon. The early commercial pioneers of FM and FM stereo were evangelical in their pursuit of success. They never doubted that FM would one day surpass AM in listenership, because they held to the belief that a quality product or service always finds its place at the top in the American freeenterprise system.

Courtesy Lynn Christian.

Fig 5.26 One of the pioneers of commercial FM broadcasting, Lynn Christian (right), gets help straightening his tie from commentator Paul Harvey.

Courtesy Lynn Christian and ABC Radio.

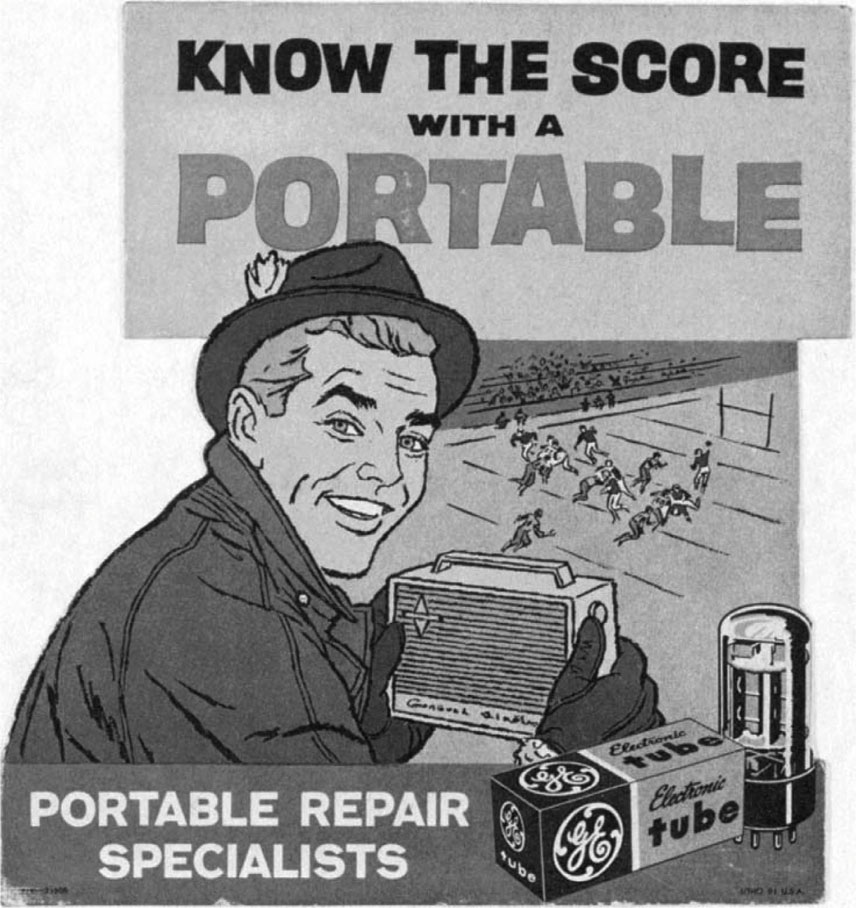

Fig 5.27 The 1950s saw many innovations in the design of portable radios.

On another political front, Congress amended Section 315 of the Communications Act of 1934 to exempt news programs from the requirement that stations provide equal time for all bona fide candidates for a given elective office. In adding that the news exemption did not relieve stations of the responsibility of presenting different sides of controversial issues, Congress established what many jurists, attorneys, and FCC officials interpreted as a specification of the Fairness Doctrine in the Act.

Fig 5.28 Portable radios with tubes were gradually replaced by transistor sets in the 1950s and 1960s.

But no sooner did broadcasting think it was again on an even keel than another scandal broke—this time, payola in radio. FCC hearings and congressional investigations in 1959 and through much of 1960 showed clearly that a large number of disc jockeys, including some of the most respected ones, took bribes in exchange for promoting certain records. At the same time, there were charges of “plugola”—whereby program directors, producers, and personalities accepted products or services from companies in exchange for giving their wares free plugs on the air. The result was congressional legislation and FCC rules (1) requiring announcements of the sources of any cash or other remuneration received relating to program content and (2) banning deceptive programming. Although in the ensuing years no further serious allegations of rigged audience participation shows have occurred, charges of payola and plugola have surfaced many times and on occasion have prompted legal action by the FCC and other federal authorities.