Chapter SEVEN

The Shifting

Q and A and Jiggle

The new decade began as the previous one had ended. Vietnam was topic number one in 1970, with broadcasting expanding its coverage of nationwide protests as the protests themselves escalated. There was much to cover, including the National Guard’s killing of student protesters at Kent State and Jackson State universities. Kent State, where the students were white, received then and still receives strong media attention; Jackson State, where the students were black, was and is still largely ignored by the media.

President Richard Nixon was unhappy with broadcasting’s coverage of events. Believing that television and radio were distorting his policies and purposes for political reasons, he did not hesitate to attack the press—electronic and print—as biased. Nixon established a new governmental communications organization, the White House Office of Telecommunications Policy (OTP), appointing Clay T. (Tom) Whitehead as director. The OTP was designed to be both an initiating and a coordi-nating point for the nation’s communications development. Through the OTP, Nixon was in a position to determine long- and short-range policy, including policy toward broadcasting. Tom Whitehead threatened broadcasters that if they didn’t “correct imbalance or consistent bias” toward the administration, they would be held “fully responsible at license renewal time.” Believing that the PBS network was also guilty of liberal bias in its programming, Nixon had Whitehead attempt to drive a wedge between the nation’s public broadcasting stations and PBS. Although some broadcasters cooperated with the administration, most were unwilling to be intimidated.

PLURIA MARSHALL

CEO OF THE NATION AL BLACK MEDIA COALITION , WHICH “MADE A DIFFERENCE ”

I came into the field of broadcast activism through my work with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in Houston. In 1971, I was heading Houston’s “Operation Breadbasket,” one of the SCLC operations that Jesse Jackson had headed. We were doing what we could in Houston—lawsuits, citizen pressure, boycotts—to get racist companies to hire some black employees. And we got a lot of jobs opened up. But the media, which were, after all, controlled by big business and big businessmen, were against us and made everything we did look sinister. They refused to acknowledge our successes or even be fair in their coverage of our activities.

That didn’t surprise us, because radio and television stations by and large had few or no black or Hispanic employees and weren’t providing programs that recognized the needs of the large black and Hispanic populations of the Houston area. So, in 1971 we challenged the licenses of 11 stations, and in 1974 we challenged eight more, under an organization that was called Black Citizens for Media Access.

A number of civil rights activists like myself throughout the country realized how important the media were in efforts for civil rights and equal rights for blacks, Hispanics, other people of color, and women. A man named Bill Wright had been traveling throughout the country training people like me, in various cities, how to fight for media access and fairness. He was then heading an organization called BEST, Black Efforts for Soul in Television. Under Bill Wright’s leadership, a group of us gathered in Washington, D.C., in 1973 as the organizing body of NBMC, the National Black Media Coalition. Bill Wright was the “Godfather” of the whole movement.

Jim McCullough became the head of NBMC. At the end of 1974, I moved from Houston to Washington to become NBMC’s unpaid executive director, and in 1975 I became CEO when McCullough left. But we still had little monetary support and in 1976 I moved back to Houston, from where I continued to run NBMC.

We filed hundreds of petitions with the FCC, challenging stations’ licenses. The Citizens Communication Center was getting grant money to act as attorneys for us. But we didn’t get a share of the money, which kept them afloat, to help keep us afloat. In a way we were being used, and in 1978 we broke off with Citizens Communication Center.

We managed to get some funding and in 1980 I returned to Washington as the paid CEO of NBMC. One of our major successes was with the Gannett Company. They wanted to buy Combined Communications. While most citizen groups were against extending their monopoly power, we were able to come to an agreement to support Gannett; they would see to it that Ragan Henry would become the first black to own a TV network affiliate. This was a huge step forward that no other organization had given us.

The first big grant for NBMC was from Gannett in 1981, and they’ve been providing grants since. Gannett is one of 40 or 50 companies that have been giving us support. By 1984 we were making big strides. We were suing any broadcasting company that discriminated against blacks. One of our big actions for equal opportunity was against the Times-Mirror Company. They agreed to provide about $2 million to facilitate black station ownership and fund communications scholarships for black students, among other things, and they increased their number of black employees to 10% in three years.

We managed to really change the attitudes of media owners toward blacks in the industry. Even lack of cooperation from other groups that should have helped us, such as the National Association of Black Journalists—too many of them were dependent for their jobs and promotions on the very companies we were suing—didn’t keep us from keeping our eye on the prize.

After a while even the FCC—maybe because it knew we’d continue to kick butt if they didn’t act—was sometimes willing to take action on its own against stations. For example, there’s the case of WXBM-FM, in Milton, Florida. We brought it to the attention of the FCC, and the FCC found the station guilty of discriminatory practices. The station then corrected those practices, but the FCC didn’t let it off the hook, and set it for hearing because of its past practices.

Another example: NBMC led the way in the only major affirmative action victory against broadcasting in the Supreme Court. In the recent Shurburg case, out of Hartford, Connecticut, and the Metro case, from Orlando, Florida, the Supreme Court upheld the FCC’s minority preference policy. I want to note that both of these were Hispanic cases—the NBMC doesn’t only deal with black cases but acts on behalf of all groups denied equal opportunity in employment, ownership, and programming.

One of our most significant ongoing projects is our Employment Resource Center, where we match employment opportunities in the communications industry with qualified black professionals. Through our Resource Center we receive information on several hundred media employment opportunities during a month, and we are in touch with a network of black professionals who we advise, counsel, and refer to these positions. Through our referral activities we have probably helped well over 5,000 persons in their employment endeavors.

We’ve made a helluva lot of difference. People either love us or they hate us. We think that’s just fine!

Courtesy Pluria Marshall.

Fig 7.1 Pluria Marshall.

Courtesy Pluria Marshall.

While the White House was unhappy with some broadcasters, broadcasters were unhappy with some segments of the public. The fervor of the 1960s civil rights revolutions spawned a number of citizen groups seeking an end to discrimination and stereotyping—racism and sexism—in electronic media. Black organizations filed petitions to deny license renewals of stations they believed were not providing equal opportunities in employment and fairness in programming. Hispanic groups protested negative images of Hispanics on the air; an example was their forcing the removal of the “Frito Bandito” commercial. Asian-American groups, heretofore generally uninvolved, began to express their concerns. Women’s organizations began to take action against sexist portrayals of females in advertising and in programs and to push the industry to hire and promote on the basis of merit rather than gender. The FCC instituted Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) requirements for stations, including the filing of annual reports on employment and affirmative action policies. An EEO office was established by the FCC to monitor licensees; it continued into the 1990s. Fearing the possibility of delay of license renewals as well as excessive legal expenditures, a number of stations made agreements with the petitioning groups to provide more equitable employment opportunities and to be more sensitive in their programming.

The continuing war in Vietnam and growing environmental problems prompted other citizen groups to seek what they felt would be fairer media coverage of their concerns. Their attempts to invoke the Fairness Doctrine were unsuccessful. The FCC turned down antiwar organizations’ requests for airtime to counter the generally supportive approach to the Vietnam War taken by broadcasting. Stations wouldn’t even sell commercial time to antiwar groups. One organization that tried to buy time, Business Executives Move for Peace, appealed to the FCC, which ruled that advertising did not fall under the Fairness Doctrine. Friends of the Earth, an environmental group, filed a complaint with the FCC after it was unable to obtain free airtime or paid advertising time for antipollution messages to counter the ads placed by gasoline companies and automobile manufacturers; the FCC turned the group down.

It was a busy year for the FCC. It approved a Prime Time Access Rule (PTAR), which limited stations in the top 50 markets to no more than three hours of prime-time (7:00–11:00 p.m., EST) network programming, excluding news, beginning September 1, 1971. It also barred networks from acquiring financial and syndication rights (called finsyn) to independently produced programs. For producers, this step opened the door to the big bucks from syndication of successful shows and to a continuing controversy that in the early 1990s brought attempts to repeal or modify finsyn.

The FCC also began to crack down on what it felt were the evils of broadcast monopolies. Relying on the scarcity principle—unlike newspapers, which can proliferate as long as there are enough printing presses, the number of broadcast stations is limited because the available spectrum for broadcast frequencies is limited—the FCC established the duopoly rule. The duopoly rule prohibited the operator of a fulltime TV, AM, or FM station from acquiring another station in the same market.

A challenge to a previous FCC ruling authorizing pay TV reached the Supreme Court in 1970; the FCC was upheld. Although broadcasters were unhappy with some FCC actions, most FCC rulings supported the broadcasting industry. For example, one FCC policy statement affirmed that an existing licensee would be given priority in the event that one or more other applicants contested its license at renewal time. This policy was challenged by a public interest organization, the Citizens Communications Center, and was overturned by a federal court the following year. The policy had been designed to allay licensees’ fears following the unprecedented revocation of the license of WHDH; but now licensees had to pay special attention to serving the public interest.

Fig 7.2 The U.S. Postal Service commemorates early broadcast innovations.

The FTC pushed stations and advertisers, too. It acted against misleading and fraudulent advertising on TV and issued a ruling that gave offenders the choice of either stopping their commercials for a year or admitting their past erroneous claims by posting corrective ads.

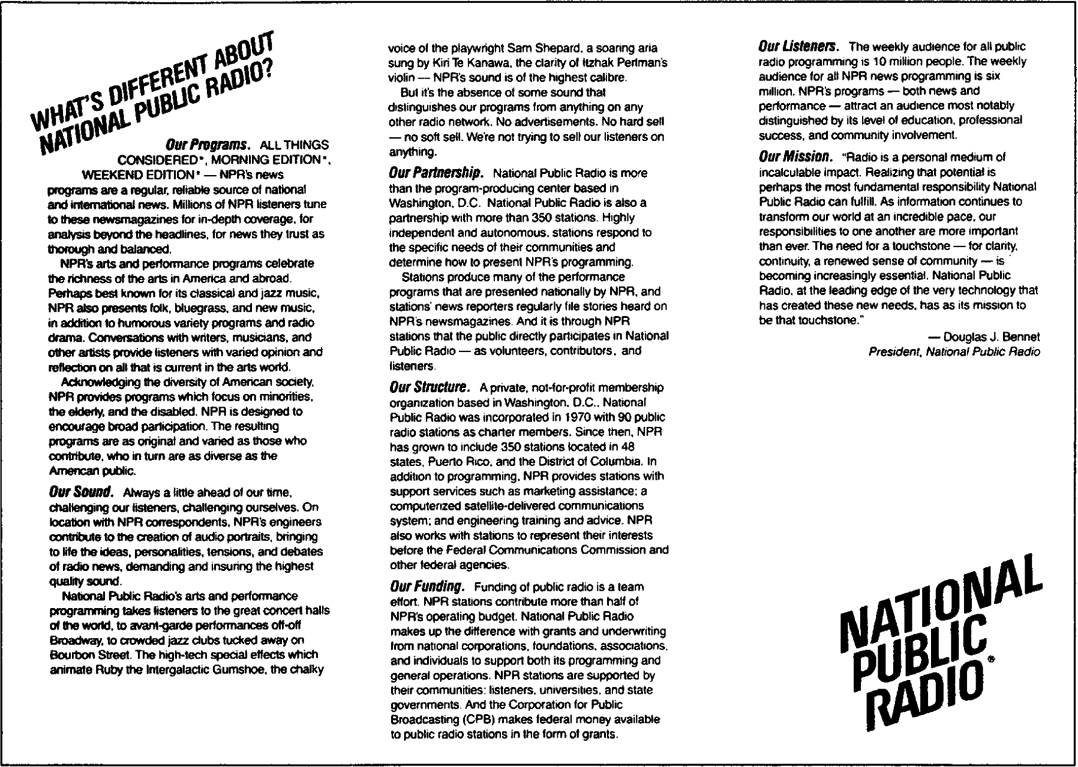

The broadcasting industry continued to grow, even as it aged, with some of it passing into history—such as David Sarnoff’s resignation as chairman of the board of RCA due to ill health, and his replacement by his son Robert, who had been president of RCA—and some of it presaging the future—such as the founding of the NPR network.

In 1970, 95% of all U.S. households had television. Commercial TV was reaching the saturation stage, with an increase of only little more than 100 stations from 1965 to 1970, for a total of 677. Public television, given the impetus of the Public Broadcasting Act, the facilitating work of the FCC’s Educational (Public) Broadcasting Branch, and a surge of federal funds, almost doubled its presence in five years, from 99 stations in 1965 to 188 in 1970. Although only 8% of U.S. homes yet had cable, that was three times as many as five years earlier, and cable TV was on the edge of taking off. Auto radios reached the 90% mark for the first time. Radio, finding its new niche, grew. There were 4,300 AM stations in 1970, 250 more than in 1965. But it was FM that emerged from a painful childhood into a blossoming adolescence, with an increase of 1,270 stations in five years, for a total of 2,200 in 1970. This growth was attributable in great part to FM’s gradual move toward more mainstream, pop music formats. Sixty percent of the radio sets in the country now had FM reception.

Fig 7.3 National Public Radio becomes a vital new broadcast service.

Courtesy NPR.

1971

The rebellion against the establishment grew. CBS broadcast The Selling of the Pentagon, a documentary showing how the U.S. military spent huge sums of money to propagandize the public to support higher military budgets. Coming at a time when Americans were more and more outraged over the U.S. military action in Vietnam, the documentary angered both the public and the Congress. The House held hearings and subpoenaed all CBS footage prepared for the documentary. CBS’s president, Frank Stanton, refused to comply. Despite pressure from Vice President Agnew, the FCC, and many members of Congress, broadcasting’s First Amendment rights were upheld.

A further blow to the integrity of the Pentagon and the White House was publication of the so-called “Pentagon Papers” by The New York Times. Taken from official files by whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg, and their release facilitated by U.S. Senator Mike Gravel, the documents showed how the government was deliberately misleading the public regarding the conduct and status of the war in Vietnam. The Supreme Court upheld the First Amendment and refused to allow the government to exercise prior restraint of the press. Broadcasting covered the scandal. An even stronger blow against the U.S. action in Southeast Asia was television’s coverage of the trial of Lieutenant William L. Calley, whose platoon massacred civilians at My Lai in Vietnam. With indications that this was only one of a number of atrocities by U.S. forces, more Americans turned against continuing U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

Citizen groups got a boost in regard to broadcasting’s coverage of controversial issues when the federal courts (1) overturned the FCC’s ban on the sale of time to present alternative viewpoints on controversial issues and (2) ruled that ads for automobiles and leaded gas fell under the Fairness Doctrine, entitling environmental groups to respond. These court decisions posed additional problems for the increasingly beleaguered White House, and President Nixon’s director of OTP, Tom Whitehead, called for abolition of the Fairness Doctrine. Such calls would be heard often in subsequent years, but it wasn’t until President Ronald Reagan vetoed a Fairness Law in 1987 that the Fairness Doctrine was actually abolished by the FCC.

The FCC, pressured by more and more groups throughout the country filing renewal challenges against more and more stations, enacted an Ascertainment of Community Needs rule. All stations were required to determine the 10 most significant issues in their communities of service and at the end of each year report to the FCC on the extent to which they had dealt with those issues in their programming. This requirement was also eliminated in the later deregulatory period.

In response to strong public support of a petition from Action for Children’s Television (ACT), the FCC proposed rules relating to quality and advertising practices on children’s programming. The FCC didn’t actually issue any such rules, however, until Congress passed a bill in 1990 limiting the amount of advertising time on children’s TV shows and requiring the FCC to consider children’s programming in its renewal process.

The FCC also tackled another problem—one that is still unresolved in the 2000s—when it issued a policy warning broadcasters against playing songs that contained drug-related lyrics. The commission was immediately attacked—as it still is on this issue—from a number of sources on grounds of censorship and violation of the First Amendment.

New kinds of programs made a mark in 1971. In commercial television, Norman Lear’s All in the Family made its debut, showing that a sitcom with content and controversy could be successful. Lear generated the prototype, motivation, and economic justification for the social-reality sitcom on U.S. TV. The Mary Tyler Moore Show, also debuting in 1971, established the genre of sophisticated sitcom comedy, seen in later years in successors such as Murphy Brown. Besides Lear, producers such as Grant Tinker and Garry Marshall put their stamp on the decade by contributing a myriad of popular (if not profound) sitcoms, many of which were spinoffs of the originals.

Norman Lear Changes the Landscape of Television

With the sound of flushing toilet, Norman Lear’s All in the Family rocked the world of American television. All in the Family altered the conventions of television comedy by tackling subjects and using heretofore blasphemous language that had been assiduously avoided. Debuting in January 1971, All in the Family may have been the beginning of “reality” programming, snubbing the conformist belief that audiences would not take to programs dealing with real, often controversial issues. Following the bland, idealized families that ruled 1950s sitcoms and the weird fantasy plot lines of the 1960s, All in the Family tackled subjects that reflected what was actually occurring in a country undergoing a seismic cultural shift. With cunningly scathing dialogue, All in the Family exposed the ills of contemporary society by addressing such hot-button topics as menopause, rape, impotency, homosexuality, racism, women’s rights, the Vietnam War, and the Nixon Administration, with its main protagonists, the conservative, head-of-the household Archie Bunker and his liberal, live-in son-in-law, Mike Stivic. After a slow start, All in the Family proved a ratings winner for many seasons during the 1970s and spun off an entire cottage industry of Lear-produced topical shows such as The Jeffersons, Maude, Sanford and Son, and Good Times that forever changed the face of television sitcoms and perhaps the entire medium.

In radio, NPR began broadcasting with a network of 90 stations. Although its programming was applauded, its criteria for network membership, supported by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), were criticized and continue to be criticized even today. Using federal funds, NPR provides its services only to those stations wealthy enough to have five full-time, paid staff members plus NPR-designated power and time on the air. The less affluent noncommercial radio stations—including low budget college and university licensees, many of them predominantly black institutions with marginal public support and needing the tax-supported services more than the richer stations—continue to be denied NPR network membership.

As part of its franchise requirements, cable opened the doors to public participation in the media with the establishment of access channels in New York City. For the first time, any and all members of the public had the opportunity to present their ideas and talents to the rest of the public through the media on a regular, supported basis.

Two archrival broadcast pioneers died in 1971: Philo Farnsworth, generally recognized as the father of American television and who got his first patent for electronic television in 1927, passed away at 64; David Sarnoff, credited with building the RCA and NBC communication empires, died at 80.

1972

Live international television coverage via satellite was established in 1972 through three significant events. Broadcasting magazine called the broadcasts by all three TV networks of President Nixon’s landmark visit to China a “milestone in broadcast history.” A few months later the networks did the same for Nixon’s trip to the Soviet Union for a summit meeting in Moscow. ABC kept its cameras going as the coverage of the Olympic games turned from triumph into tragedy when Palestinian terrorists took 11 members of the Israeli team hostage and later killed them.

The FCC entered a crossroads of regulatory policy. It was deluged by mass filings from many citizen groups challenging the license renewals of hundreds of stations across the country. In most cases the challenges resulted in agreements between the stations and the citizen groups, principally in the areas of providing equal employment opportunity and more sensitivity in programming in multicultural and women’s areas. Concomitantly, Benjamin L. Hooks became the first African American to be appointed to the FCC—or, for that matter, to any federal regulatory agency. Reflecting the mood of the country, Commissioner Hooks began pushing for equal employment opportunity action in the communications industry. Some of his attempts were successful; others were not. For example, one of the authors of this book worked with him on a proposal to study the racial composition of the boards of directors of public broadcasting stations, many of which at the time appeared to have even fewer minorities than commercial stations did. The public broadcasting establishment, including such organizations as the National Association of Educational Broadcasters (NAEB), and some of the other commissioners were furious, and their opposition caused the study to be abandoned.

The beginning of reregulation took place that year when the FCC dropped a number of technical requirements regarding station operations. Within the decade, reregulation would become deregulation.

Television breathed a partial sigh of relief when the surgeon general’s report on television violence came out. The report found no definitive causal relationship between violence on TV and aggressive behavior in the average child; it did, however, find that TV violence could trigger aggressive behavior in some children, especially those already prone to violent acts. The report generated concerns that continue today. The FTC did its part to try to protect children, monitoring ads on “kidvid,” as children’s television was called, as well as continuing to take action against misleading advertising in general.

Television Violence: Forty Years after the Report

Nearly 40 years after the release of the massive (six-volume) congressionally funded probe, collectively referred to as the Surgeon General’s Report, the issue of the effects of television violence remains contentious. The weight of the evidence from the thousands of studies, of varying precision, seems to affirm the connection. Yet there are still doubters who find the evidence inconclusive or contradictory. So, what’s the answer? There doesn’t seem to be an all-encompassing one. A leader of the confirmative side is media scholar George Comstock, who was with the Rand Corporation, which produced much of the scientific research for the surgeon general (Television and Human Behavior, 1975). Recently Comstock concluded an exhaustive meta-analysis that confirmed a statistical causal relationship between television and aggressive or antisocial behavior. A meta-analysis is basically an “analysis of analysis,” a quantitative aggregation of a large body of disparate studies. Comstock found that though the overall variation may be small (there is no perfect cause and effect connection), which suggests televised violence is just one among numerous causes, the direction of the findings is undisputedly in the same positive direction. Skeptics point to the large degree of unexplained variation, meaning the many nontelevision contributors to violent behavior.

Unable to intimidate most broadcasters into presenting the news as he thought it should be presented, President Nixon had the Department of Justice filed antitrust suits against all three networks. The suits were later dismissed. While not letting up on what it believed were the left-leaning prejudices of commercial broadcasters, the Nixon administration took dead aim at public broadcasting as well, the public affairs programs of which the White House considered harmful to the government and, in fact, Communist tainted. President Nixon tried to end funding for public broadcasting and succeeded in seeing its support reduced, even vetoing one of the CPB budget bills. Nevertheless, public broadcasting continued to develop new programs, one of which—hardly controversial—made its debut in 1972 and became a household favorite, Julia Child’s The French Chef. (See Child’s comments in the 1960s chapter.)

Vietnam was not forgotten, and its horrors were reemphasized in a new sitcom, set in Korea, that became a brilliant, bitter satire on war: M*A*S*H.

The year 1972 saw technical advances that forecast the kinds of competitive communication systems that would result in serious challenges to broadcast television, including a drastic drop in prime-time network viewing, within 20 years. A number of firsts took place:

• The first demonstration of a videodisc using laser-beam scanning, by MCA and Philips

• The first home videogame on the market, Magnavox’s Odyssey

• The first prerecorded videocassettes for rental and sale to the public

• The first pay-cable channels for public subscription, including Home Box Office (HBO would also be the first cable system to use satellite distribution, in 1975)

• The new technical equipment that dominated that year’s NAB convention was, ironically, the computer

Monday Night Football Transforms the Prime-Time Audience

If All in the Family revolutionized the content of television, Monday Night Football (MNF) forever altered the composition of the prime-time audience. Conventional wisdom held that women controlled television during evenings, and they did not like football. The National Football League (NFL) relationship with television began modestly, highlighted by the ill-fated DuMont Network’s Saturday night package over its tiny collection of affiliates in the early 1950s. However, it was the league’s regular Sunday afternoon schedule that attracted broadcasters, which needed something other than religious and political programming to make the day profitable. Soon double-headers and pregame shows pushed “public service” programming to the periphery. The NFL had longed for a weeknight prime-time series and found a willing partner in ABC, which, as a constant distant third in the ratings battle, had little to lose. Under the tutelage of Roone Arledge, president of ABC Sports, the venture proved to be a rousing success. Arledge, recognizing that he needed more than a football game to attract viewers, stressed entertainment over athletics, focusing on personal vignettes combined with a compelling cast of characters in the broadcast booth that attracted enough non-NFL aficionados to become a staple of prime-time television each fall.

BILL SIEMERING

RADIO EXECUTIVE PRODUCER, SOUNDPRINT, AND CREATOR OF NPR’S ALL THINGS CONSIDERED

Gunpowder was invented in a Chinese kitchen when charcoal, sulfur, and salt peter accidentally came together. In like manner, elements came together at WBFO in Buffalo, New York, to form the essential values of public radio. The station, the university, and the city were in the cauldron of the cultural and political revolution of the times. An exceptional staff was the catalyst in this mixture, which resulted in new assumptions about the content and sound of radio that became NPR. The mixture included a spirit of learning by doing, concern for people and ideas, and the sound possibilities of radio.

As a university station, experimentation and risk taking were natural. We did this, for example, with the composition City Links WBFO, by Mary Anne Amacher, which brought the sounds of the city on five lines live into the studio, where they were mixed and broadcast for 28 hours. Listeners also heard broadcasts of the city council and writers John Barth, Leslie Fiedler, and Robert Creely reading and talking about their writing.

WBFO pioneered in multicultural programming. We established a storefront broadcast facility on Jefferson Avenue, where African-American and Hispanic residents planned and produced 25 hours of programming a week. We sponsored a Black Arts Festival with photographers, paintings, live jazz, and a mural in the studio depicting the history of Afro-American communications, ending with the satellite facility. “The Airwaves Belong to the People” was given new grassroots meaning and was the slogan of the staff. We traveled to the Tuscarora reservation and produced a series on the Iroquois Confederacy.

These and other experiences informed the mission and goals statement of NPR, which I wrote in 1970. Before All Things Considered had a title, I wrote that it “… will not substitute superficial blandness for genuine diversity of regions, values, cultural and ethnic minorities which comprise American society; it will speak with many voices and many dialects.… There may be views of the world from poets, men and women of ideas, interpretive comments from scholars.”

Our commitment to these ideals was grounded in experiences in the community. We saw how commercial media ignored conditions of minorities on the east side; we witnessed the results of anger at injustice; we saw familiar store windows shattered and then covered with dull the process of this change and worked to plywood; we smelled the acrid smoke of burning buildings; we felt the tear gas burn our eyes; we knew the fear in the streets.

Later, unrest came to the university during a long student strike and 300 police occupied the campus. Reporting on the turmoil within the university—as a university-licensed station—tested our journalistic independence and our professional skills and shattered some old assumptions. Truth, we discovered, was reflected through different perceptions of reality, and we broadcast a full spectrum of opinion. Amid tear gas in the building and some administration objections, we stayed on the air, and the [local] Courier Express commended the coverage as a “beacon of light” amid the chaos. WBFO emerged with a new professional respect within the community and the university.

Even though similar events were going on in other parts of the country, it was the exceptional group of people at WBFO who saw public radio as an active participant in the process of this change and worked to define public radio as more than an alternative to commercial radio. Five WBFO staff members joined NPR. Many others went on to distinguish themselves in journalism and other professions. I wrote in the NPR mission statement:

The total service should be trustworthy, enhance intellectual development, expand knowledge, deepen aural aesthetic enjoyment, increase the pleasure of living in a pluralistic society and result in a service to listeners which makes them more responsive, informed human beings and intelligent, responsible citizens of their communities and the world.

We tried to do that first as a kind of laboratory experiment at WBFO. Now, after 20 years of programming, that’s what public radio does nationally.

Courtesy Bill Siemering.

Fig 7.4 Bill Siemering.

Courtesy Bill Siemering.

The FCC issued, finally, its definitive cable rules in 1972. These included requirements that a local cable system must carry all local broadcast stations (those within a 60-mile radius); must delete network and syndicated programs of any distant stations it carried if such programs were on a local station (called syndex, or syndicated exclusivity); must offer a minimum of 20 channels in the top 100 markets; and must provide free-access channels for the public, education, and municipal government as well as a system-operated, local origination channel. The FCC also claimed jurisdiction over rate structures. A dozen years later, virtually all the FCC cable rules would be eliminated with the passage of the Cable Communications Policy Act of 1984.

In an attempt to generate support as they tried to compete with the stronger, principally VHF network affiliates, independent nonnetwork, mostly UHF, stations formed the Independent Television Association (INTV). In radio, AM saw that it might soon find itself in the same disadvantageous competitive position. One-third of the nation’s listeners now tuned in to FM, whose greater fidelity and stereo capacity made it superior to AM in music. Some AM stations began to move to more talk shows, and a number of those with sagging ratings saw these new talk formats hold the line and even increase their ratings. A few stations tried all-news formats for the first time, in New York, Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles.

President Nixon seemed to be overly concerned about the challenge to his reelection by Senator George McGovern, the Democratic nominee; perhaps remembering his 1960s debate against another vibrant opponent, Senator John F. Kennedy, Nixon turned down requests for TV debates with McGovern. In June 1972, the media reported what seemed like a routine story of five men caught breaking into the Democratic headquarters in the Watergate office building in Washington, D.C. The implications of that story, and the media’s subsequent role in reporting it, couldn’t even have been guessed at the time.

1973

The Vietnam War finally came to an end in 1973. Television played no small part in bringing to the American people many of the events in Southeast Asia that the government had withheld from the public, as well as bringing to the attention of government leaders citizens’ demands and actions to end the war. Watergate replaced Vietnam as the number-one topic of conversation and media coverage.

The Watergate scandal became full blown, and the networks devoted more than 300 hours of time from May to August to the Senate Watergate hearings chaired by Senator Sam Irvin. The American people saw the very worst of their political system. But the system survived. President Nixon’s statement, “I have never heard or seen such outrageous, vicious, distorted reporting in 27 years of public life,” did not fool the public; nor did his “I am not a crook” plea.

To add even more coals to the fire that was consuming the Nixon White House, television viewers watched with morbid fascination as Nixon’s attorney general, Elliot Richardson, resigned rather than obey the President’s orders to fire Archibald Cox, the special Watergate prosecutor who was getting closer to learning Nixon’s role in the crime; Nixon had an assistant attorney general, Robert Bork, do the dirty work. (Bork became a federal judge and was subsequently nominated by President Ronald Reagan to the Supreme Court, but he was not confirmed by the Senate.) As though that weren’t enough, the public saw even more corruption in the White House as they watched the resignation, in disgrace, of Vice President Agnew amid corruption charges.

The rebellion and scandals were too much for Americans, who began to yearn for the placidity of the 1950s, slowly turning to the conservative acquiescence of the Eisenhower years. The soaring, highly sensitive 1960s glided to a flat-bellied landing of 1970s insensitivity. CBS, under pressure from its affiliates, canceled Sticks and Bones, a highly regarded anti–Vietnam War drama about a blinded veteran. The Supreme Court overturned the lower courts and decided that the Fairness Doctrine did not after all apply to television and radio advertising and that no one had the right of paid access to present alternative viewpoints. The FCC modified the PTAR, giving the networks a bit more leeway. The commission cracked down on what was called “topless radio,” a short-lived phenomenon in which talk-show hosts encouraged people at home, principally women, to call in and talk about their sexual problems, experiences, techniques, and fantasies. The ratings of stations carrying these shows shot up. Finally, fines and the threat of fines and possible loss of licenses brought topless radio to a halt—though in later years, similar shows would be permitted on radio and television when the talk-show personality had a “Dr.” in front of his or her name.

Carl McIntire, the owner of WXUR-AM-FM in Media, Pennsylvania, the principal in the infamous Red Lion case, lost his appeal to the Supreme Court to retain his stations’ licenses, and within a few months he opened a pirate radio station offshore, in the Atlantic Ocean; it lasted only about two weeks before its operations were stopped by a court injunction.

Public broadcasting was undergoing an upheaval, encouraged by the Nixon administration in its attempt to make public stations more locally oriented to reduce what the administration believed was the left-leaning content of network-controlled programs. After a bitter battle for control between CPB and PBS, a compromise was reached that gave the PBS stations more autonomy over programming decisions.

Black participation in the media made some advances in 1973. The first black-owned television station in the country, WGPR-TV in Detroit, began operations. And the National Black Network, primarily a radio news organization, started with 41 affiliates.

Technical advances continued apace in 1973. The first small portable TV camera, the Ikegami HL-33, made its debut. The first fiber-optic system was installed. Panasonic gave the first demonstration of high-definition television (HDTV). The first multipoint distribution service (MDS) system began operating; now called multichannel multipoint distribution service (MMDS), it operates a point-to-point microwave service as a commercial common carrier and is sometimes referred to as wireless cable. In addition, Western Union received the first authorization for a domestic satellite.

Commercial time continued to grow more expensive, requiring an increasing number of sponsors to support a given program and resulting in the virtual disappearance of ad agencies’ absolute influence over programs. A sponsor could, of course, still threaten to withdraw, but with multiple sponsors such threats had less effect on networks than in previous years, and rarely did they succumb to such pressure. More often the networks cooperated with large conservative citizen groups, such as the Rev. Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority, whose membership could, on short notice, generate thousands of letters of protest against programs or performers that were not in agreement with the organization’s religious, political, or other beliefs. It was not a 1950s-style blacklist; it was more a stifling of viewpoints other than those of a self-styled moral majority.

RICK WRIGHT

PROFESSOR, SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY, AND RADIO PERFORMER

In the early 1970s, I deejayed at several stations, most of which featured Afro-American–oriented programming. Many black radio pioneers helped pave the way for minorities in the medium. I’m currently at work on a book that will tell the story of this important aspect of the broadcast century. Among those who made a unique contribution to black radio and broadcasting in general are Jack Gibson back in the early 1920s in Chicago; B. B. King and Rufus Thomas at WDIA-AM in Memphis; Jack Holmes and Mrs. Leola Dyson at WRAP-AM and Starr Merritt, King Hot Dog the Great, and Bob Jackson in Norfolk; Rodney Jones at WVON-AM and Sid McCoy and Merrie Dee in Chicago; Joko Henderson, Frankie Crocker, Chuck Leonard, The Dixie Drifter, Del Shields, Hank Spann, Martha Dean, Gary Byrd, and Hal Jackson in New York City; Martha Jean the Queen in Detroit; The Magnificent Montaque and Herman Griffin in Los Angeles; Norfley Whitted in Durham; Ben Miles and Tiger Tom Mitchell in Richmond; Georgie Woods and Jimmy Bishop in Philadelphia; Bill Haywood in Raleigh; Daddy O. and Larry Williams in Winston-Salem; Merrill Watson in Greensboro; Doctor Jive and Wild Child in Boston; Bob King, Cliff Holland, Jerry Boulding, and The Nighthawk in Washington, D.C.; Hoppy Adams in Annapolis; and The Moonman and Hot Rod in Baltimore. There are a host of other great Afro-American air personalities who left their special mark on the medium, and I salute them all.

Courtesy Rick Wright.

Fig 7.5 Rick Wright.

Courtesy Rick Wright.

1974

What were people watching on television in 1974? Politics, scandal, resignation, soap opera, and violence—both make-believe and real-life.

The real-life versions came out of the Watergate hearings of 1973. In August 1974 the networks covered the House impeachment proceedings against President Nixon. A week later the television cameras shifted to Nixon himself, who became the first U.S. President to resign in disgrace. More than 40 million people watched his resignation speech, and probably more than 100 million saw it repeated on later news specials. A federal judge ordered the Watergate tapes—the “smoking guns”—released to broadcasters, but the high drama itself was over and the tapes were anticlimactic.

Other real-life dramas on TV were the Senate Communications Subcommittee’s hearings on televised violence and the intensive media coverage of the kidnapping of heiress Patty Hearst, a story that would stay on broadcasting’s top burner for years. Whose words and images did the public hang onto, to learn of the important events of the world? First and foremost, Walter Cronkite at CBS, then John Chancellor at NBC, and finally Harry Reasoner and Howard K. Smith at ABC.

Make-believe violence was expensive. NBC paid a then-record $10 million for the right to show the movie The Godfather. Make-believe soap operas cost less but lasted longer. A new series from Britain, Upstairs, Downstairs, made its debut on public television’s Masterpiece Theatre. For 68 weeks the public stayed glued to the tribulations of an Edwardian English family, the Bellamys, and their entourage of servants. For many Americans, however, the highest drama of the year was broadcasting’s coverage of Henry Aaron breaking Babe Ruth’s home-run record.

The FCC had its ups and downs under a new chair, Richard E. Wiley, who succeeded Dean Burch. On one hand, the FCC received the plaudits of many citizen groups when it ordered revocation of the station licenses of the Alabama Educational Television Commission on grounds of racial discrimination in programming and employment. On the other hand, it was cited by the U.S. Civil Rights Commission as one of five federal independent agencies guilty of not protecting the civil rights of minorities and women in the industries it was supposed to regulate.

Technical advances in broadcasting continued. Satellites made news with the launch of Western Union’s Westar, the country’s first domestic satellite, and with RCA’s use, for the first time, of a domestic satellite for communications services. Forebodings to some and good tidings to others of things to come was the use of an IBM computer to run the WLOX-TV (Biloxi, Mississippi) transmitter by remote control, under special approval from the FCC.

Cable, continuing its slow but steady growth, got a boost from the Supreme Court, which ruled that the Copyright Act did not apply to TV broadcast signals carried by local cable systems. Cable could legally carry broadcasting’s copyrighted programs without paying a fee.

1975

The FCC’s most significant action in 1975 was its approval of a cross-ownership rule, which affected newspapers as well as broadcast stations. The rule barred future joint ownership of a daily English-language newspaper and a radio or television station in the same market. It gave owners of such information-monopoly combinations in small markets five years in which to divest one of the media properties. Court rulings in subsequent years made the prohibition even more stringent than the Commission initially intended. Other tough actions by the FCC that year were (1) revocation of some radio stations’ licenses because of misconduct, such as news slanting and false advertising, and (2) denial of approval of a cable system on grounds of bribery.

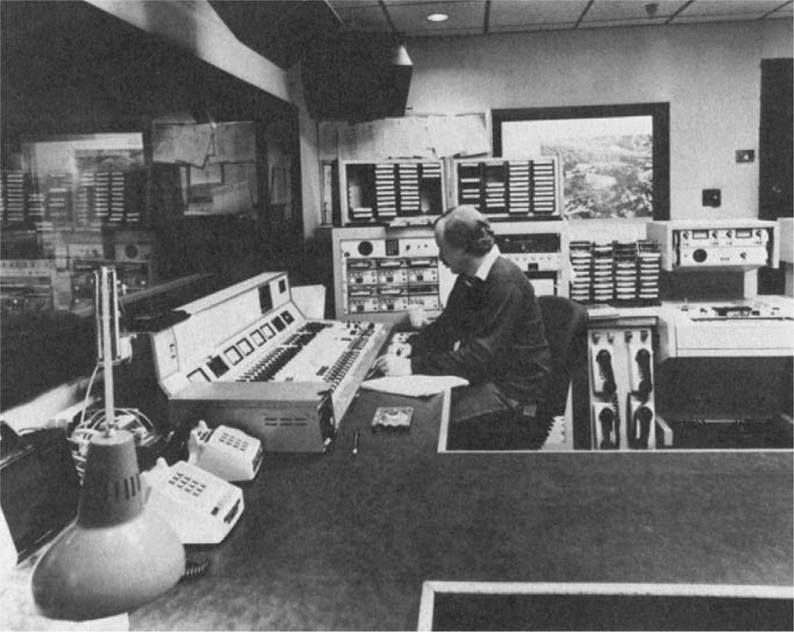

Fig 7.6 Automation systems have been a mainstay for many radio stations since the 1960s.

Courtesy IGM Communications.

Everything grew: television, radio, and cable. Cable now claimed 15% penetration of the country’s TV homes. About 96% of U.S. households now had TV sets. AM had added some 150 stations since 1970, for a total of 4,450, but FM had added 450, to reach 2,600 stations on the air. Noncommercial FM did better percentagewise, adding more than 300 stations, for a total of 717. Commercial television grew more slowly, increasing by only 30 stations in five years, to 706. Noncommercial, or public, television did better, adding more than 60 stations, for a total of 247. The bottom-line statistic is the one that pleased broadcasters most: TV advertising increased 50% from 1970 to 1975, to $5.2 billion; radio advertising grew by the same percentage, to $2 billion.

Radio’s comeback was by now well established, and new, specialized radio networks appeared. In 1975 NBC set up a news and information service to 33 stations. Ironically, Canada’s Radio-Television Commission (CRTC) proposed AM and FM uses diametrically opposite to what was occurring in the United States: AM for popular music and general information; FM for in-depth information and culturally significant programming.

Television’s program innovation was a new NBC show with risqué, irreverent satire and farce that launched such personalities as John Belushi, Gilda Radner, and Eddie Murphy into stardom—Saturday Night Live. CBS offered a technical innovation: electronic news gathering (ENG), with portable minicameras and recorders that took TV journalists into places where few had gone before. Cable, too, proposed something new, one of its many threats to broadcasting: satellite transmission by HBO to local cable systems. Satellite-to-home possibilities—called direct broadcast satellite (DBS)—frightened broadcasters, and the three networks opposed such possibilities in hearings at the FCC.

Fig 7.7 TV becomes portable.

Courtesy David Sarnoff Library.

1976

Three more presidents were replaced in 1976. Lawrence K. Grossman succeeded Hartford N. Gunn, the first president of PBS; CBS’s president, Arthur Taylor, was fired by William Paley because he was allegedly “too big for his britches”; and the nation’s Republican President, Gerald Ford, was replaced by the American people because, according to some pundits, he wasn’t big enough for his, and thus Jimmy Carter, a Democrat and Georgia governor, became the new head of state. During the campaign Ford and Carter engaged in three highly publicized television debates, the first since 1960. An estimated 90 million to 100 million people saw the first debate, but for 28 minutes they didn’t hear it. It was suspended for that length of time when the sound went out; the networks had neglected to provide backup equipment.

On another government communications front, in the legislative branch, the new chair of the House Communications Subcommittee, Representative Lionel Van Deerlin, began a series of unsuccessful efforts to write a new communications act. He argued that the Communications Act of 1934 was obsolete because it was not designed to address the problems of the many new and emerging technologies. Another legislative action affecting communications was passage of a revised copyright law that, for the first time, required cable and public broadcasting to pay royalties. A “compulsory license” that entitled cable to retransmit copyrighted TV programs for a statutory fee paid to a copyright tribunal for distribution to broadcasters was still a matter of controversy in the 1990s.

In the executive branch of government, following years of controversy with Nixon appointees, the White House OTP moved toward moderation with the appointment of a moderate Republican, Thomas Houser, as director. In another corner of the executive branch, the FCC was again in trouble with the third branch of government, the judiciary. In 1975 the new FCC chair, Richard Wiley, had worked out an agreement with the networks and the NAB for what was called family viewing time. Programs with sex and violence or other content deemed inappropriate for family viewing would not be aired between 7:00 and 9:00 p.m. (EST), and this provision was incorporated into the NAB’s television code. Protests from producers, civil liberties organizations, creative artists, and others filled the nonbroadcast air until, in 1976, a federal court ruled that the family viewing time agreement was in violation of the First Amendment; having been instigated by and implemented because of government, it was deemed unconstitutional. The FCC’s faux pas was not quite ameliorated by its opening of 17 more citizens band (CB) channels for the more than 20 million CB users in the country.

Fig 7.8 The role of women in network news gradually increased in the 1970s.

Courtesy Irving Fang.

GEORGE HERMAN

FORMER CBS NEWS REPORTER

My first election night at CBS News was 1944 and my task was lowly. My bosses said: “Herman, you were a math major at Dartmouth, you do the math.” This was before computers, so I became a computer. Side by side with my colleague Alice Weel, I received all election copy from the wires of the AP, UP, and INS. Typically it would read: “With 154 precincts reporting out of 2,347, Franklin D. Roosevelt leads Thomas E. Dewey 123,457 to 107,658.” With a quick slip of my slide rule (remember, I was a math major), I would figure out the percentage of precincts reporting and, later on, the percentage of votes for each candidate. I then scribbled those numbers on the copy and passed it along the chain of command. There two things happened. The numbers were added to already known totals for that state and the new total read through a phone line to a page, wearing a headset and standing on a scaffold in front of one of the huge blackboards arcing across one whole side of the huge studio. The page would hastily erase his old numbers and chalk the new total onto that state’s line on the board so our anchormen could see it. And if the reporting region was important enough and the returns exciting enough, the slip of paper with my scribbled figures went to an anchorman to read on the air.

A series of us, adding, dividing, scribbling numbers on slips of paper and passing them along by hand and by headset, served as the computer—the pages and blackboards were the digital readout from which anchormen and analysts noted trends, figured totals. This was before television came back from its wartime freeze and we worked in our shirtsleeves, proud of our informality and sneering to each other about NBC, where President Sarnoff had made the election-night crew dress in tuxedos to impress the visitors he brought in.

It was the same drill in 1948—informal, but neatened up for the occasional TV shot of the crowded studio and its busy chalkboards. I had noticed that at the conventions the delegate totals were displayed by the simple expedient of gluing 3- × 5-inch unlined pads to the wall: a pad, then a painted-on comma, then three pads, a painted-on decimal point, then two more pads. A stage hand wrote a single digit on each pad to show the total figure. When it changed he quietly tore off the top pages, crayoned the new digits on the fresh sheets and let the old ones fall out of sight to the floor.

In 1952 as a war correspondent I listened to the returns in Korea as they came in over Armed Forces Radio. But in 1956 I was back in the election-night studio. This time there was a new gimmick. Instead of pads glued to the wall, the TV people had cut pairs of tiny slits in the wall and inserted endless belts of flexible plastic film in through the top slit and out through the bottom one. Digits were painted top-to-bottom on the belts, and stage hands behind the wall pulled the belts through the slots so that the single appropriate digit was visible on the camera side of the wall. Presto! Digital readout (from the digits of the stagehands).

It’s hard to realize that today the digits, the actual numbers, don’t exist anywhere in reality, aren’t written or painted or displayed by alphanumeric gadgets. They are merely strings of electric charges hidden inside a computer and displayed on the monitors of the reporters and, at the discretion of the director, displayed in fancy artwork on the home TV screen, updated, manipulated, all percentages neatly inserted by the computer. Goodbye slide rule, goodbye pencil and paper.

Courtesy George Herman.

Fig 7.9 George Herman.

Courtesy George Herman.

In the realms of programming and personalities, two significant events occurred. Rich Man, Poor Man, based on the Irwin Shaw novel, was the first miniseries, with six two-hour programs airing over seven weeks. According to Life magazine, “It paved the way for serialized dramas such as Roots, Shogun, Brideshead Revisited, and The Jewel in the Crown.” ABC and Barbara Walters struck a blow for equal rights—even as a federal equal rights constitutional amendment was failing—when ABC lured Walters away from NBC with a $1 million contract to become the first female network news anchor.

ABC had another coup with its Eleanor and Franklin, winning 11 Emmys, the most ever for one program. CBS did well with its bicentennial-year Bicentennial Minutes, vignettes of U.S. history. Indeed, all the networks had a number of specials commemorating America’s 200th birthday. Public broadcasting got into the programming act with an antidote to the increasingly “infotainment” news programs of the commercial networks, The MacNeil Report. Public broadcasting and viewers with hearing impairments got help from the FCC when the commission approved vertical blanking interval lines for closed captions, which are visible on TV sets with special decoders.

A more widespread technical advance was Sony’s new 0.5-inch Betamax videocassette deck for recording TV shows off the air and for playback. Its price of $1,300 was less than the record-and-play unit with integrated monitor that Sony introduced the previous year for $2,300 and that seemed to be going nowhere. The Betamax was the first step in what has become a national phenomenon, causing profound changes in TV viewing habits and creating a new high-profit industry.

Cable also made a breakthrough when Ted Turner’s WTCG (now WTBS) in Atlanta became the first TV station to be distributed via satellite to cable systems throughout the country. Radio didn’t do so well. NBC Radio’s News and Information network, which had begun with high hopes only a year before, folded after huge monetary losses.

Any history of broadcasting has to make note of an event dedicated to broadcasting history. In 1976, with its first five years of funding guaranteed by William Paley, the Museum of Broadcasting opened in New York City.

1977

The year 1977 clearly signified the end of the social conscience era of the 1960s. Entertainment was king, the king died, long live the king: to many Americans, the most important radio and television broadcasts in 1977 were the reports of Elvis Presley’s death from a drug overdose. The ethical attitudes of the times were clear. Rather than being vilified for his role in intensifying a drug culture among the nation’s youth, Presley received media canonization. Considerably less attention was paid to the official pardons in 1977 of people whose consciences led to their refusals to fight in the discredited Vietnam War.

The FCC reflected the lack of social concern of much of America, as more and more of its actions tended to serve the private rather than the public interest. For many broadcasters, the FCC’s new deregulatory attitude was a breath of fresh air, relieving the business of broadcasting from what it felt was the too-heavy hand of government. The commission repealed its radio rules from 1941, issuing a new, less rigorous policy statement; it modified the equal time rules; it put its inquiry on network station relations, as Broadcasting magazine couched it, “in deep freeze” (the U.S. General Accounting Office later began its own network investigation); the U.S. Court of Appeals affirmed the FCC’s policy of leaving children’s television to self-regulation; the FCC eliminated several cable rules; the Civil Rights Commission again criticized the FCC and the broadcast industry for inadequate equal employment opportunity action, and a federal court stopped the FCC from exempting stations with fewer than 10 employees from filing EEO reports. In the fall of 1977 public interest groups looked for better times, from their points of view, with President Carter’s appointment of Charles D. Ferris as chair of the FCC, although Ferris’s lack of experience in communications had been raised at his Senate confirmation hearings. Their high hopes were not to be realized, however; the Ferris FCC moved even further away from the heyday of public interest regulation and toward the proindustry deregulation of the 1980s.

Although television programming included innovative social content, the medium was attacked for what appeared to be increasing emphasis on violence and sex. However, social content was found both in comedy and in drama. Soap was a satire with social commentary and included—rare for that time—an openly gay character, played by newcomer Billy Crystal. Roots, based on Alex Haley’s book, became the most watched program in TV history over its eight-day schedule. The saga of a family, from its roots as kidnapped Africans forced into slavery in the United States, had ratings in the middle 40s and shares in the high 60s, with its final episode watched by an estimated 80 million people. This series helped ABC win the prime-time ratings race for the first time, ending 20 years of CBS domination. Its success reinforced the miniseries concept, and networks moved ahead with plans for more of them.

Violence was nothing new, but “jiggle,” or “T and A,” introduced the previous year with the Charlie’s Angels series, now became TV’s principal ratings booster. Criticism about violence and sex grew from citizen and professional organizations such as the National Parents-Teachers Association and the American Medical Association. To its television code the NAB added prohibitions concerning obscenity and profanity; however, the voluntary nature of the code resulted in little impact.

With the media coverage of the Hanafi Muslims’ taking of hostages in Washington, D.C.—one of the first modern-day terrorist acts on U.S. soil—broadcasting was criticized for encouraging violence through its news approach. Broadcasters were accused of exacerbating the problem and were urged not to provide a platform for terrorists.

Other broadcasting-related events in Washington, D.C., were President Carter’s increased use of the media, including a call-in, question-and-answer program; approval by the House of Representatives to allow broadcast coverage of its proceedings; and a failed attempt by Representative Lionel Van Deerlin’s House Communications Subcommittee to rewrite the Communications Act. Internationally, the World Administrative Radio Conference (WARC) set aside spectrum space (11.7–12.2 GHz) for DBS.

The National Association of Television and Radio Announcers (NATRA), established in the 1960s as an alternative for black broadcasters to what was perceived as the racially discriminatory American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (AFTRA), had been ahead of its time and was no longer an important factor in broadcasting. But the time seemed right for another minority organization. The National Association of Black Owned Broadcasters (NABOB) was formed. By the end of the year, however, blacks, Hispanics, and other minorities owned only 1% of the almost 10,000 television and radio stations in the United States.

On the technical front, broadcasting conventions saw demonstration of a new technology: digital audio. Still, it wouldn’t be until the 1990s that digital audio broadcasting (DAB) would be established as the wave of the immediate future. In Columbus, Ohio, Warner Cable began an experiment that many thought would revolutionize video for the home: interactive, two-way cable. The experiment, QUBE, though highly touted and praised, never obtained enough subscribers to be successful, and it folded in 1984. The subsequent development of newer transmission technologies and sources of software suggests that in the near future interactive video, through such systems as videotex, will begin to take its place in U.S. homes.

1978

Technological innovations seemed to occur almost every other week in 1978. Computers were beginning to be critical factors in broadcasting. Microprocessors revolutionized audio consoles, switchers, character generators, and other equipment. PBS became the first television network to move from terrestrial to satellite distribution of its programs, with Westar providing feeds to 280 public television stations. Cellular telephones made their debut in Chicago. The first laser videodisc players were unveiled. So were the first home rear-projection TVs. It had taken a quarter of a century, but for the first time, in 1978, the number of color television sets in use in the United States exceeded the number of monochrome sets.

The jokes about violence on television—“And that’s only the news”—were validated with network coverage of such events as the mass suicides in Jonestown, Guyana, and the murders of San Francisco’s mayor and a gay member of the city council. Another kind of violence was perceived by the FTC: the effects of commercials on children. Under Michael Pertschuk, its new chair dedicated to the public interest, the FTC proposed rules that would eliminate commercials from children’s programs. Such rules, some of them aimed at curtailing the potential medical harm caused by the high sugar contents of breakfast cereals that ads encouraged children to eat, never reached fruition. Pertschuk was disqualified by the courts from participation in the rule making; Congress ordered the FTC to stop the proceedings, and, when the FTC refused, the House of Representatives voted the commission a “zero” budget for 1979, thus putting the FTC out of business. The FTC dropped the rule making. To be certain that it would not be resumed, in 1980 the Senate passed a resolution forbidding the FTC to take further action on the matter. The power of industry over government and communications has rarely been exemplified more effectively.

NORMAN CORWIN

RADIO’S POET LAUREATE, WRITER, PRODUCER, TEACHER

First a panel lit up, reading ON THE AIR

A shingle hung out in the sky, denoting Open For Broadcast.

Then words and music.

That embarkation is barely started toward Andromeda

Cruising at the speed of starlight

And already we are ripe for jubilee.

Babes born on that night

Show gray, show wrinkles where they should be showing,

Are not as fast afoot as once they were

But since they ride together with us on the float we call our home

They join the party.

Years of the electric ear!

The heavens crackling with report: farflung, nearby, idle, consequential,

The worst of bad news and the best of good

Seizures and frenzies of opinion

The massive respirations of government and commerce

Sofa-sitters taken by kilocycle to the ball park, the concert hall, the scene of the crime

Dramas that let us dress the sets ourselves

Preachments and prizefights

The time at the tone, the weather will be, and now for a word,

The coming of wars and freeways

Outcroppings of fragmented peace

Singing commercials and The Messiah. And then the eye.

Cyclops the one-eyed giant put to work

As picture-maker to uncountable galleries

No longer the imagined but the living face in the glowing mosaic

Not only the tap of the dancing foot but the swirl of the twirling skirt

Not only the bounding arpeggio but the dazzle of running fingers.

No eye has roved like the video eye

Away and beyond the reach of earth

Out to the moon and onto it

Footprints in primordial dust umbilical walks in the deeps of space

Sprayed on the tube in front of the chair or up on the wall in the bedroom.

Blood, too.

Between that night and this

The cruellest half of the cruellest century:

The resentful atom, furious when provoked

Depots of extermination

Bomb blasts and body counts

Corpses on campuses

Terror the diplomat

Olympic torch flaring over a funeral bier

Gunsights on the boulevard the motel porch the hotel kitchen the parking lot

Murder on camera: the shot seen round the world.

Is it any wonder the eye of Cyclops

From time to time was bloodshot?

But look out across the anniversary:

Antennae like stubble on rooftops

Drawing light and shadow and polychromes out of the general yonder

Galvanic clouds raining anchormen and action

In-laws of the sitcom, outlaws of the west

Contagions of laughter

Pandemic widows of the football weeks

Guesses and giveaways: riches on the instant: Cinderella liveth!

The stubborn noble enterprise of human rights

Whodunits and doves

Hawks and ferrets:

Now sir will you tell the committee

Well sir at that point in time

Protocols of mayhem

Animated mice men messages

By authority of the Commission.

Babes born on this night will,

By our second jubilee

Find few of us now here, still in the flesh,

But all summonable out of silence.

To you, then, sons and daughters:

Members of tomorrow’s weddings and the families to follow:

Play us back not as a quaintness but a memoir of a contentious time

Sift out past and you will find among the gravel, gemstones of a kind,

But do not dwell on us: instead,

Enter the future as the future enters you

And what you see, the lens will see

And what you do, the ribbon will record

And what you say, be stored with every inflection in its place.

In cribs tonight, what ballerinas playing with their toes?

Yowling for the nipple, what incipient Homer?

What toddler picking up her dolls and baubles

Will write a poem or find a cure to make an epoch happier?

Who on a scooter-car will transfer to a wagon set for Mars?

Meanwhile Cyclops will not be indifferent

For he is worked by mortals made of malleable metals;

And glass can weep and dust fall on a lens.

This is the eye in which our inheritors will see themselves as in a vibrant mirror

With all their pores and passions.

We whose celebration runs out in this hour

Send you benisons to last you to the year 2000 and far beyond:

May you give shelter to the muses

Melt down your barriers

Pay no more dues to war

Make liberty a cult, and love of liberty a deep addiction

Adorn yourselves with sunny aspects and ornaments of honor.

There end our greetings,

But we must send a postscript to Andromeda:

When at last this reaches you

Know that it went out from a small planet

With one moon and a billion families

A globe with salted oceans and green mantles.

We on this spinning outpost share with you

The same infinity of time and space

So when you spot us on your sets and tune us in

And ponder what you see and hear,

We ask this only:

That you do not judge us yet,

For there is more to come.

A poem written in honor of CBS’s fiftieth birthday. Courtesy Norman Corwin.

Fig 7.10 Producer and writer Norman Corwin cues his performers during a 1940s radio program.

Courtesy Norman Corwin.

While one of the FTC’s most famous tribulations began in 1978, one of the FCC’s ended. In 1973 the FCC had received a complaint from a father that he and his young son (then 15) heard on their car radio an indecent program from WBAI-FM, a Pacifica station in New York. The material in question was performer George Carlin’s “Seven Dirty Words” routine. The case reached the Supreme Court in 1978. The Communications Act, the Court, or the FCC had not up to that time designated what kind of specific language or material was “indecent” or “obscene.” Previous court decisions had used such phrases as “community standards,” “no redeeming value,” “appeals to prurient interests,” and similar generalities. An indecency case in broadcasting, however, had never reached the Supreme Court before, and both the FCC and broadcasters hoped that finally a clear definition and designation of what was considered indecent and obscene would be forthcoming. The Court, however, didn’t go beyond the “seven dirty words.” It stated that the FCC did have a right, under the obscenity, profanity, and indecency provision of the Communications Act, to take action against any station that it deemed was in violation of that standard. It also decided that the FCC was correct in judging the “Seven Dirty Words” presentation to be indecent because its references to sexual and excretory functions violated community standards. Moreover, the Court said it would judge each future case on its individual merits. Other than the “seven dirty words,” then, the FCC is still unable to tell inquiring broadcasters whether any specific piece of questionable material they propose to air would or would not be in violation. The FCC simply says that the licensee must make the judgment, and that if there are complaints and if the FCC investigates and finds that the material in question was indecent or obscene, then the station may be punished; clearly, a Catch-22 for broadcasters. In the late 1980s the FCC established stronger anti-indecency rules, but, as discussed in the 1980s chapter, still without specific usable definitions.

Fig 7.11 The look of the radio production studio in the late 1970s.

Another FCC action in 1978 that was not successfully resolved in the 1990s was the authorization of AM stereo broadcasting. AM stations continued to lose ground to FM’s better fidelity, and prognostications did not include much of AM in radio’s future. AM stereo was one possible competitive solution. Although in 1980 the FCC approved the Magnavox AM stereo system, out of a number of applicants, as the standard, strong objections from the industry and a general lack of interest in the Magnavox system resulted in the commission’s reevaluation of other potential systems. AM stereo was put on hold. Finally, in 1982 the FCC decided not to decide. It approved five different systems and would let the marketplace decide; presumably, the best one would eventually win out. But AM radio couldn’t wait for “eventually.” Because the systems were not all compatible, neither stations nor the public could move ahead until one system emerged. As FM continued to outstrip AM, AM owners asked the FCC to designate one system; the FCC refused to do so. As Broadcast Engineering magazine stated some years later, “That’s where AM stereo still is—waiting for the marketplace to decide.” In the 1990s, except for some scattered markets, stereo still had not fully come to AM radio. Whether the market-place theory in practice has made it too late for AM’s revival still remains to be seen.

In other government actions in 1978, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration was established in the Department of Commerce, replacing the old White House OTP and its successor, the Office of Telecommunications Policy of the Commerce Department.

Van Deerlin’s House Communications Subcommittee made another attempt to rewrite the Communications Act of 1934 and approved and sent to the floor of the House a bill to do so. Highly charged lobbying began by industry, citizen groups, and even government officials. The bill, which would have abolished the FCC and created a new regulatory structure, failed to pass.

While the FCC attempted to resurrect some consumer-oriented actions, it also nullified others. It reopened the 1977 inquiry it had dropped on network-affiliate relations; it was criticized by the U.S. Court of Appeals for giving incumbent licensees automatic preference over challengers at renewal time; and it eliminated certificates of compliance with FCC requirements for cable systems.

One FCC action in 1978 was the adoption of a policy making it easier for minorities to become licensees of broadcast stations. Minority applicants were given preference in obtaining licenses for new stations and in buying stations up for sale. In subsequent years, attempts were made to abolish such preferences. Although for a period the FCC suspended application of the rules, public and congressional pressures forced the commission to reinstate them. The Reagan administration attempted to abolish the minority-preference rules but was blocked by Congress. The Bush administration asked the Supreme Court to declare such rules unconstitutional. In 1990 the Supreme Court held the rules to be constitutional. Even so, in the early 1990s minorities held only 3.5% of all broadcast licenses.

In 1978 another part of the past of broadcasting died and part of its future arrived. Clarence Dill, coauthor of the Dill–White Act—the Radio Act of 1927—and a contributor to the Communications Act of 1934, died at the age of 93. The first pay-per-view option on television, for classic movies, began at KWHY in Los Angeles. Additionally, the first video rental/sale store opened.

1979

The saga of the Communications Act continued in 1979. Two Senate bills and one House bill rewriting the act were introduced. None succeeded. By the end of the year, Representative Van Deerlin, who had taken the lead in seeking a new act, gave up and decided to concentrate on changing the common carrier provisions of the old act.

Under the old act, the FCC began consideration of broad deregulation of radio, to let the marketplace substitute for government guidelines. The Supreme Court mandated deregulation for one of the FCC’s rules, the one that required cable systems to provide free-access channels for the public, education, and local government. The FCC implemented Section 312 of the act by requiring the networks to sell the Carter–Mondale campaign 30 minutes of airtime, which the networks had previously refused to do. The FCC contended that reasonable access was necessary to prevent the networks from deciding who and how much the public may hear in Presidential races. The networks took the FCC to court, contending that it had violated broadcasting’s First Amendment rights. In 1981 the Supreme Court upheld the FCC. Nevertheless, as subsequent events would prove, networks and individual stations—through their acquiesced manipulation by political campaigns, their use of money as a criterion for coverage, their adoption of “sound bites” as opposed to substance, and the weakening of the political equal time rules of Section 315 in the 1980s—effectively gained much control of the political process by deciding which candidates would get exposure and what the exposure would be like.

Another FCC action was prompted by the International Telecommunications Unions’ (ITU) extension of the AM band in the United States to 1,705 kc. With support of the NTIA, the commission began a series of rulemakings to compress individual station bandwidth and, with the new spectrum space, add additional frequencies. Radio broadcasters, as might be expected, fought against the creation of new competitor stations, but by mid-1991 the new bandwidth had been established although there was little interest in it because of changes in the market.

The FCC took a stand on children’s television. Prodded by citizen groups, including ACT, and motivated by the regulatory attempts of the FTC, in 1979 the FCC released a report criticizing the industry’s compliance with the FCC’s 1974 guidelines. The commission expressed concern over the failure to increase children’s educational programming, to eliminate manipulative practices in presenting commercials, and to decrease the amount of advertising. One network, ABC, did reduce commercial time on its children’s shows. Nonetheless, the 1974 guidelines were just that—guidelines. There were no enforcement provisions, and despite its critical report, the FCC did not propose rules that would have required compliance.

Notwithstanding its long experience covering the news and its new equipment, including electronic news gathering (ENG), broadcasting failed the American public in reporting the most potentially catastrophic event of the year in the United States: the nuclear accident at Three Mile Island. A Presidential commission found that the media were unprepared for and unable to give the public effective coverage of this story.

TERRY GROSS

HOST OF NPR’S FRESH AIR

Nothing on radio had ever surprised me more than hearing one of my roommates proclaim she was a lesbian. It was 1973, and she was appearing as a guest on Womanpower, a feminist program on WBFO, Buffalo’s NPR affiliate on the state university campus. I was puzzled and a little offended that she would go public to strangers who happened to be listening, before letting her own roommates know. Somehow, in a radio studio she felt secure enough to reveal intimacies she was not yet comfortable confiding to her own friends.

I desperately wanted to work in a medium that could have this effect on someone, and for a program that went that far. I was lucky. My roommate’s new lover was one of the producers of the feminist program, but she was leaving for the lesbian-feminist show. My friend gave me the name and phone number of one of the remaining producers and encouraged me to call.

It didn’t matter that I had no radio experience. The producers were almost as committed to training other women as they were to getting the program on the air. They were convinced that the mass media would continue to ignore or misinterpret the women’s movement until women were in a position to make editorial decisions and report the stories. And that couldn’t happen until there were women who knew their way around the studio and control room.