After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

• Define sports marketing and discuss how the sports industry is related to the entertainment industry.

• Describe a marketing orientation and how the sports industry can use a marketing orientation.

• Examine the growth of the sports industry.

• Discuss the simplified model of the consumer–supplier relationship in the sports industry.

• Explain the different types of sports consumers.

• Identify historical trends and significant impacts of sport marketing practices.

• Define sports products and discuss the various types of sports products.

• Understand the different producers and intermediaries in the simplified model of the consumer–supplier relationship in the sports industry.

• Discuss the elements in the sports marketing mix.

• Explain the exchange process and why it is important to sports marketers.

• Outline the elements of the strategic sports marketing process.

Mary is a typical “soccer mom.” At the moment, she is trying to determine how to persuade the local dry cleaner to provide uniforms for her daughter’s Catholic Youth Organization soccer team.

George is the president of the local Chamber of Commerce. The 10-year plan for the metropolitan area calls for developing four new sporting events that will draw local support while providing national visibility for this growing metropolitan area.

Sam is an events coordinator for the local 10k road race, which is an annual fund raiser for fighting lung disease. He is faced with the difficult task of trying to determine how much to charge for the event to maximize participation and proceeds for charity.

Ramiz is the Athletic Director for State University. In recent years, the men’s basketball team has done well in postseason play; therefore, ESPN has offered to broadcast several games this season. Unfortunately, three of the games will have to be played at 10 P.M. local time to accommodate the broadcaster’s schedule. Ramiz is concerned about the effect this will have on season ticket holders because two of the games are on weeknights. He knows that the last athletic director was fired because the local fans and boosters believed that he was not sensitive to their concerns.

Ad 1.1 Concept of sports marketing

Source: Reprinted with permission. www.cartoonstock.com

Susie works for a sports marketing agency that is representing a professional sport franchise. The franchise is planning to expand its international market presence. She is challenged with establishing relationships in a foreign environment which hosts a unique set of cultural values and customs.

The American Marketing Association defines marketing as the activity, set of institutions, and processes for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large.1 Sport and entertainment have been defined in a variety of ways, nonetheless, most definitions inclusively included terms such as: indulgement, divergence, and/or engagement; for valued outcomes of enjoyment, pleasure or amusement. Although sport may often consist of a more competitve nature, both are inclusive of retaining diverse exchange platforms. These diverse platforms provide a variety of engagement opportunities and yet, uniquely, are comprised of an array of outcomes that are distinctly similar.

Sports marketing is “the specific application of marketing principles and processes to sport products and to the marketing of non-sports products through association with sport.” The sports industry is experiencing tremendous growth and sports marketing plays an important role in this dynamic industry. Many people mistakenly think of sports marketing as promotions or sports agents saying, “Show me the money.” As the previous examples illustrate, sports marketing is more complex and dynamic. The study and practice of sports marketing is complex, yet interesting because of the unique nature of the sports industry.

Mary, the soccer mom, is trying to secure a sponsorship; that is, she needs to convince the local dry cleaner that they will enjoy a benefit by associating their service (dry cleaning) with a kids’ soccer team.

As president of the Chamber of Commerce, George needs to determine which sports products will best satisfy his local customers’ needs for sports entertainment while marketing the city to a larger and remote audience.

In marketing terms, Sam is trying to decide on the best pricing strategy for his sporting event; Ramiz is faced with the challenge of balancing the needs of two market segments for his team’s products; and Susie, the sport marketer, is seeking to persuade international populations of the relevance of diversifying their sport culture. As you can see, each marketing challenge is complex and requires careful planning.

To succeed in sports marketing one needs to understand both the sports industry and the specific application of marketing principles and processes to sports contexts. In the next section, we introduce you to the sports industry. Throughout this book, we continue to elaborate on ways in which the unique characteristics of this industry complicate strategic marketing decisions. After discussing the sports industry, we review basic marketing principles and processes with an emphasis on how these principles and processes must be adapted to the sports context.

Understanding the sports industry

Historical development of sports marketing in (North) America

The evolution of sports marketing strategies to meet the needs and wants of the consumer continues to be a priority of practitioners worldwide. Today’s realm of sports marketing and sponsorship, though a more dramatically effective and a much more diverse platform, is vaguely similar to what many identify as its origin, 776 BC, when the Olympic Games began. Marketers for the Ancient Olympic Games were no amateurs; these perceptive businessmen realized early on that an affiliation with a popular athlete could produce a potentially lucrative relationship.2 Throughout its history, sport in some form has existed and, though the common-day term of sports marketing had not yet emerged, the process of utilizing marketing and promotion strategies to enhance delivery and production has been evident.

The roots of sports marketing in North America can be traced back to the 1850s and 1860s when many businesses, recognizing the popularity of sport, attempted to create linkages to enhance commercial opportunities by marketing through sport. Two events of this era in particular, one collegiate and one professional, illustrate the use of marketing through sport and helped lay a foundation for utilization of sport as a service medium in North America.

In 1852, a railroad official together with a group of local businessmen believed that they could garner enough interest in the marketing and staging of the event to produce economic and commercial profits. The end result was the first inter-collegiate match between Harvard University and Yale University – a two-mile rowing contest. This event took place at a quiet summer resort called Center Harbor on Lake Winnipesaukee, New Hampshire. The result demonstrated that the entrepreneurs were able to create a positive economic impact on the region, enhancing rail traffic, hotels occupancy, and revenue for the host city.

The second event is tied to the late 1850s and early 1860s and the commercialization of the new sport of baseball. Tobacco companies partnered with professional baseball leagues and began using photographs of the teams to help sell their products and services. These companies made baseball cards with pictures of the teams and players and then inserted them in cigarette packets to boost and enhance brand loyalties. Though the strategies of distribution have been altered over the years – that is, transition from the use of cigarettes, to bubblegum, to today’s independent packages – these strategies laid the foundation for a new industry; the memorabilia and card collecting/trading market that exists today.

North American sport experienced a variety of popularity struggles in the late 1800s and early 1900s. A demand for reform arose and threatened sport at a variety of levels. In 1906, with the assistance of President Theodore Roosevelt, efforts were made to transform the image of sport. Strategies and regulations were implemented to enhance the safety and appeal of the game. Rules, regulations, and the control of lurking controversies, such as the controversy distinguishing the amateur and professional status of athletes, became a primary emphasis of sport organizations.

Although the early 1920s were a period of relative calm in American society, the country was intrigued by the newest technology of the day, the radio. Marketers, sports administrators, and broadcasters alike sought to integrate sports utilizing this medium; a medium at the time that many believed symbolized a coming age of enlightenment. For, as Beville noted, no other medium has changed the everyday lives of Americans as quickly and irrevocably as radio.3 In 1921, the first American baseball broadcast occurred from Forbes Field. Though this broadcast was deemed a success, marketers of the era struggled to transcend executive opinions for some believed that the broadcast would have a negative impact upon attendance and demand.

In the 1930s and 1940s sports organizations utilized radio to enhance team revenue streams. Innovative marketers began relying on the radio to get their message across to the common man. In 1936, this same forum was used as a marketing and public relations campaign to pronounce the success of Jessie Owens and his Olympic debut.

Radio provided the impetus to solidify the era of patronage; however, the invention that soon followed remains to this day the most significant communication medium that has influenced and aided the development of sports. Who knew what sportscaster Bill Stern questioned and introduced in 1939 would enhance the growth and development of sports marketing practices for decades? The display platform, the television, though airing two mediocre baseball teams battling for fourth place, provided an incredibly formidable and profitable union between sport and the American public. The television provided a means for sports organizations to expand their market presence and a unique opportunity for marketers to engage their publics. The notion of a “picture being worth a thousand words” became a reality with the invention and its intervention and presentation of sports.

In 1946, radio and television broadcasting revenues together contributed only 3.0 percent of MLB revenues, but that rose to 16.8 percent by 1956. Executives such as Bill Veeck became innovators of sports marketing, utilizing radio and in-game promotional strategies to further market their teams. Owners, players, broadcasters, and fans recognized the variety of impacts television would have on the presentation of sports. In fact, television giant CBS dropped its Sunday afternoon public service emphasis to provide for a 12-week professional football broadcast.

An American consumer in the 1950s loved and demanded sports. Participation trends and fan demand steadily increased. Sports became a symbol of changing times in the United States. In 1957, Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in baseball. The importance of this event in helping the Civil Rights Movement in the United States is evident, but it also proved the social power of sports in American culture and the impact that could be made utilizing sports as a communication medium. By including minorities in sports, the market grew. Cultural acceptance, along with media presence, provided the American public with a means to link personalities and audiences.

This prominence led to the identity era of the 1960s. Chuck Taylor/Converse, Muhammad Ali/Adidas/Champion, Jim Brown/NFL, Mickey Mantle/Major League Baseball, Arnold Palmer/PGA and Arnie’s Army, to name a few, all became marketable entities. Marketers began to utilize sport to establish linkages with consumer publics. Endorsements and sponsorships evolved. Representation through agents became the norm for those who had prominence. For example, sport marketing giant International Management Group (IMG) founder Mark McCormack and golf great Arnold Palmer instituted a legendary handshake deal which lasted more than 40 years.

The 1970s included several evolutionary events in sports marketing. Consumer demand for sport continued to rise, while existing and emerging commercial entities such as Nike, Adidas, Puma, and others fought to snatch up endorsement opportunities. Sponsorships of products by athletes continued to emerge as a trend of the decade. In fact, the first corporate sponsorship of a stadium venue occurred in Buffalo in 1973 – Rich Stadium. Buffalo-based Rich Products agreed to pay $37.5 million, $1.5 million per year over 25 years.4

In the 1970s athletes too began to make a presence. Athletes such as Joe Nammath became sex symbols while advertisers began to realize that athletes could add a unique element to any product in the context of an endorsement campaign; e.g., Jack Nicolas, Muhammad Ali, Mario Andretti to name a few. This was further demonstrated at the end of the decade when Coke utilized Pittsburgh Steelers tackle, “Mean Joe Green,” to star in one of the most acclaimed Coke advertisements ever.

Throughout the 1970s mergers, acquisitions, and governmental ramifications were prominent. Title IX entitled rights for women to have further access to participate in sports. Advertising laws, that forced the tobacco industry off the TV airways, freed funding for alternative marketing and advertising strategies. These tobacco companies could avert the law by developing sponsorship arrangements, thus affording the growth of events such as Virginia Slims Tennis and NASCAR Winston Cup.

Television markets were further expanded due to cable offerings and afforded network growth. Television began bringing teams from across the country into the spotlight. A health craze swept the nation further complementing commercial and consumer ties to sport. Entrepreneurs like Ted Turner, in 1976, were afforded an opportunity to develop and market a superstation, while ESPN’s founder Bill Rasmussen, in 1979, was able to introduce the first true 24-hour sports broadcasting network.

In the 1980s salaries skyrocketed and leagues saw a need to remain competitive. Increased competition created a variety of economic and financial issues. Emphasis on television revenues became a priority. The money from media contracts became important to the team’s bottom line and its ability to recruit and pay top players. Miracle workers such as NFL Commissioner, Pete Rozelle, and Olympics marketing and television guru, Richard Pound, continued to develop and enhance sponsorship and media contracts as they related to sport. Professionals such as Rozelle of the NFL, Peter Ueberroth of NBC, and Pound of the IOC had a significant impact on the explosion of so-called strategic alliances as a result of external competitive pressures such as globalism of economies and constantly advancing technologies.5

The 1980s represented the “me” decade in sports. Sporting goods were tailored to be aligned with specific sports. With the likes of Larry Bird, Magic Johnson, Joe Montana, and the introduction to Michael Jordan, fans continued through the turnstiles, disregarding the negative influences and impacts of the sky rocketing salaries, agents, greed among teams and players, drug use by athletes, and free agency. Despite or because of the greed, sports grew in popularity and became a more desirable marketing platform.

Sport sponsorship began to see double-digit growth. Sponsor dollars were abundant and even mediocre athletes began signing contracts to endorse or wear their products.6 The expansion of sponsorship as a communication medium was greatly influenced by the emergence of sports leagues and corporate involvement during the 1970s and 1980s. However, this growth did not come without resistance. Resistance by broadcasters, event managers, and consumers alike focused on the intrusion of corporate America into this restricted arena.

Many corporate CEOs became involved with sponsorship for unsubstantiated reasons; i.e., they favored a sports activity or they chose to intermingle with famous sports celebrities. Exposure through affiliation was achieved, but without justification of the return on investment. Marketing strategies varied considerably due to the limited channels of exposure, but objectives were to align corporate endorsers to enhance the linkages and exposure of the events. This growth created a corporate reliance that would create many future marketing implications.

During the Michael Jordan era of the 1990s, television had become the driving force behind almost every league, including the NFL, NBA, NHL, MLB, NCAA, and NASCAR. In fact, the majority of teams and sport organizations became reliant upon these television revenues. Increased revenue streams offered opportunities for expansion. Organizations, such as the NHL, expanded to regions of the south while others such as the NBA began to focus beyond the Americas. Sponsorship continued to enhance the dollar pool and rose at a double-digit pace. Salaries continued to skyrocket, and leagues expanded to take advantage of untapped markets. Most fans wanted to be loyal; however, struggles such as the 1993 baseball strike had a severe impact on its popularity and adversely impacted consumer loyalty. Strategies became more focused and began to emphasize the transfer of unique connotations inherent in the property and brand image.

Although the modern world of mega-million dollar sponsorships had begun, marketers questioned the cluttered environment. The driving force behind the game and its growth had become clouded. Prior to the 1990s, management’s use of sponsorship was often criticized for the cavalier and often frivolous approaches undertaken.7 During this era sponsorship became entrenched as a legitimate corporate marketing tool. It saw an unprecedented double-digit growth and that had a significant impact on image, value, recognition, and method of delivery.

In recent years, sport marketing has continued to grow, but at a more moderate pace and not without restriction or limitations. In this era of social media, listening, networking, and enhancing relationships has become a priority, whereas selling is secondary. The continued advent of technology has created a much more audience-centered universe, thus, creating a paradigm that continues to evolve and innately requires sport marketers to develop a more audience-dictated framework to overcome a host of cybermarketing issues.

Demand through technology has created an international platform, a platform encompassing numerous cultural variances. Today’s athletes are a global commodity. In today’s sports marketing environment much more is at stake than free agency and escalated player salaries. Today, organizations seek to provision resources directly to an individual, authority, or body to enable the latter to pursue some activity in return for benefits contemplated in terms of the sports market strategy, and which can be expressed in terms of corporate, marketing, or media objectives.8

Organizations such as NFL, MLB, NASCAR, and the NBA have expanded scheduled exhibitions and displays. However, the unprecedented growth of these organizations and their popularity at the international level is not without increased marketing challenges. Technology has had a significant impact on the delivery of the product. The versatility and opportunities surrounding the use of technology enables organizations the opportunity to exploit a variety of platform delivery mediums to fulfill many of the basic functions of the marketing communications mix. In this era, the demand and usage of second screen platforms prevail. Therefore, interactive positioning of a product is a key to its marketing success.

For every Winston Cup or Jordan success there are at least as many ineffective sports marketing campaigns. Many athletes today capitalize on their image more than their athletic prowess. From athletes in their primes to athletes who have made lasting impressions, endorsement deals do not necessarily end when a professional career is over. Professional athletes are aware of the effect their image has on endorsement dollars, and most are not willing, nor ready, to give up a share of endorsements. If today’s players had Babe Ruth’s devil-may-care attitude, they would likely never see the kinds of endorsement dollars the more polished, public images today are garnering.9

Today’s sport marketer recognizes that image influences the bottom line. The most prolific athletes are not always the most celebrated, and the most celebrated are often not the most gifted. However, in today’s environment all are under the microscope of media attention. Because of today’s growing media and social network influences, it is crucial for sports marketers to recognize need and define the ‘why’ as it relates to sports marketing applications. Defining the ‘why’ is crucial to its successful interpretation.

In today’s sports marketing environment there is a threshold for clutter; however, scrutiny and integrity are the demanding forces that will impact its future. Consumers will continue to demand variety in the presentation of the sports product, but they will not overlook the overcommercialized tactics often employed by sports marketers that impact the integrity and presentation of its environment.

Webster’s defines sport as “a source of diversion or a physical activity engaged in for pleasure.”10 Sport takes us away from our daily routine and gives us pleasure. Interestingly, “entertainment” is also defined as something diverting or engaging. Regardless of whether we are watching a new movie, listening to a concert, or attending an equally stirring performance by Dwayne Wade, we are being entertained.

Most consumers view movies, plays, theater, opera, or concerts as closely related forms of entertainment. Yet, for many of us, sport is different. One important way in which sport differs from other common entertainment forms is that sport is spontaneous. A play has a script and a concert has a program, but the action that entertains us in sport is spontaneous and uncontrolled by those who participate in the event. When we go to a comedic movie, we expect to laugh, and when we go to a horror movie, we expect nail biting entertainment. But the emotions we may feel when watching a sporting event are hard to determine. If it is a close contest and our team wins, we may feel excitement and joy. But if it is a boring event and our team loses, the entertainment benefit we receive is quite different. Because of its spontaneous nature, sport producers face a host of challenges that are different than those faced by most entertainment providers.

Nonetheless, successful sports organizations realize the threat of competition from other forms of entertainment. They have broadened the scope of their businesses, seeing themselves as providing “entertainment.” The emphasis on promotional events and stadium attractions that surround athletic events is evidence of this emerging entertainment orientation. Consider the NBA All-Star Game. What used to be a simple competition between the best players of the Western Conference and the best players of the Eastern Conference has turned into an entertainment extravaganza. The event (not just a game anymore) lasts for days and includes slam-dunk contests, a celebrity and rookie game, concerts, 3-point shooting competition and plenty of other events designed to promote the NBA.11 In 1982, the league created a separate division, NBA Entertainment, to focus on NBA-centered TV and movie programming. NBA TV has created original programming featuring shows like All-Access, Basketball International, Fantasy Hoops, NBA Roundtable … and Hardwood Classics. As Alan Brew, a principal at RiechesBaird (now BrandingBusiness), a brand strategy firm states, “The line between sport and entertainment has become nearly nonexistent.”12

Of course, one of the most highly visible examples of “sporttainment” is the WWE or World Wrestling Entertainment. For the past few decades, the WWE has managed to build a billion dollar empire and according to WWE.com the WWE posted revenue of $508 million in the fiscal year 2013. Live and televized entertainment accounted for 75 percent of those sales, followed by consumer products (15 percent), digital media (8 percent), and a new brand extension called WWE Studios at 2 percent.13 Vince McMahon, the founder and chairman, has been called the P. T. Barnum of our time.

The sports entertainment phenomenon is also sweeping the globe as the following Forbes Inc. narrative and video link suggests: www.forbes.com/sites/mikeozanian/2012/02/26/nfl-expansion-could-include-London/. As organizations begin to recognize the value of sport as emtertainment in this global environment it is important for sports marketers to understand why consumers are attracted. Defining what consumer needs are and how those needs relate to the global environment will further complement the marketing exchange process.

Organizations that have not recognized how sport and entertainment relate are said to suffer from marketing myopia. Coined by Theodore Levitt, marketing myopia is described as the practice of defining a business in terms of goods and services rather than in terms of the benefits sought by customers. Sports organizations can eliminate marketing myopia by focusing on meeting the needs of consumers rather than on producing and selling sports products.

The emphasis on satisfying consumers’ wants and needs is everywhere in today’s marketplace. Most successful organizations concentrate on understanding the consumer and providing a sports product that meets consumers’ needs while achieving the organization’s objectives. This way of doing business is called a marketing orientation.

Marketing-oriented organizations practice the marketing concept that organizational goals and objectives will be reached if customer needs are satisfied. Organizations employing a marketing orientation focus on understanding customer preferences and meeting these preferences through the coordinated use of marketing. An organization is marketing oriented when it engages in the following activities.14

![]() Intelligence generation – analyzing and anticipating consumer demand, monitoring the external environment, and coordinating the data collected;

Intelligence generation – analyzing and anticipating consumer demand, monitoring the external environment, and coordinating the data collected;

![]() Intelligence dissemination – sharing the information gathered in the intelligence stage;

Intelligence dissemination – sharing the information gathered in the intelligence stage;

![]() Responsiveness – acting on the information gathered to make market decisions such as designing new products and services and developing promotions that appeal to consumers.

Responsiveness – acting on the information gathered to make market decisions such as designing new products and services and developing promotions that appeal to consumers.

Using the previous criteria (intelligence gathering, intelligence dissemination, and responsiveness), one study examined the marketing orientation of minor league baseball franchises.15 Results of the study indicate that minor league baseball franchises do not have a marketing orientation and that they need to become more consumer focused. Although the study suggests that minor league baseball franchises have not moved toward a marketing orientation, more and more organizations are seeing the virtue of this philosophy.

Table 1.1 The power ranking – 25 coolest minor league stadiums

Power ranking |

Stadium |

Team |

1 |

Richmond Country Bank Ballpark |

Staten Island Yankees |

2 |

Metro Bank Ballpark |

Harrisburg Senators |

3 |

AT&T Field |

Chattanooga Lookouts |

4 |

Canal Park |

Akron Aeros |

5 |

Whitaker Bank Ballpark |

Lexington Legends |

6 |

Fieldcrest Cannon Stadium |

Kannapolis Intimidators |

7 |

Whataburger Field |

Corpus Christi Hooks |

8 |

Isotopes Park |

Albuquerque Isotopes |

9 |

Victory Field |

Indianapolis Indians |

10 |

Bright House Field |

Clearwater Phillies |

11 |

NewBridge Bank Park |

Greensboro Grasshoppers |

12 |

Dr. Pepper Ballpark |

Frisco RoughRiders |

13 |

First Energy Stadium |

Reading Phillies |

14 |

RedHawks Field at Bricktown |

Oklahoma City RedHawks |

15 |

Louisville Slugger Field |

Louisville Bats |

16 |

Coca-Cola Field |

Buffalo Bisons |

17 |

Modern Woodmen Park |

Quad Cities River Bandits |

18 |

MCU Park |

Brooklyn Cyclones |

19 |

AutoZone Park |

Memphis Redbirds |

20 |

Raley Field |

Sacramento River Cats |

21 |

Fifth Third Field |

Dayton Dragons |

22 |

Dell Diamond |

Round Rock Express |

23 |

Ripken Stadium |

Aberdeen IronBirds |

24 |

LeLacheur Park |

Lowell Spinners |

25 |

McCoy Stadium |

Pawtucket Red Sox |

Source: http://bleacherreport.com/articles/842135-power-ranking-the-25-coolest-minor-league-stadiums.

Sport has become one of the most important and universal institutions in our society. It is estimated that the sports industry generates between $480–620 billion each year, according to a recent A. T. Kearney study of sports teams, leagues, and federations.16 This includes infrastructure construction, licensed products, and live sporting events. According to Plunkett Research,17 the sports industry is twice the size of the U.S. auto industry and seven times the size of the movie industry. The industry is becoming increasingly global with respect to conventional and new media distribution fronts. This total is based on a number of diverse areas within the industry including gambling, advertising, sponsorships, etc. As ESPN founder Bill Rasmussen points out, “The games are better, and well the athletes are just amazing and it all happens 24 hours a day. America’s sports fans are insatiable.”18 For better or worse, sports are everywhere. The size of sport and the sports industry can be measured in different ways. Let us look at the industry in terms of attendance, media coverage, employment, and the global market.

Not only does sport spawn legions of “soccer moms and dads” who faithfully attend youth sport events, but also for the past several years, fans have been flocking to major league sports in record numbers. The NFL achieved peak attendance in 2007, averaging 68,702 fans per game and a 99.9 percent capacity. Although the League experienced a slight decline from 2008 to 2011, the League has been able to retain a 95 percent plus capacity. The 2013 season reflected a 96.5 percent capacity and an average game attendance of 68,373. The NFL continues to experience what many would call another prosperous year, with paid attendance of 17,304,523 fans attending. In addition, the NFL extended its television contracts through 2022, embarking on deals that will generate upwards of $3 billion a year.19

The NFL, both on and off the field, continues to strengthen the very foundation of the game. The League strives to make changes that are having a positive impact on the delivery of the game, both to consumers in person and via media outlets. According to NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell, NFL numbers are up; up in overall fan engagement, in most cases, dramatically, and interest in the NFL is expanding as they continue to grow internationally.20 In fact, for the 2014 season, the NFL announced that two games would be played in London, both games sold out months in advance. The NBA also had strong attendance in recent years. In the 2012–2013 season over 17 million fans turned out to see the action and arenas averaged 17,274 per game.

This was complementary to the 2011 season where the NBA noted that its three national TV partners all had their highest viewer ratings ever. According to the League, TNT saw a 42 percent increase, while ABC was up 38 percent and ESPN saw a 28 percent jump. Turner Sports noted its 1.6 rating was its highest in 27 years of NBA coverage and that it televised three of the five most-watched NBA regular-season games ever on cable this season. Despite fears of a labor stoppage after the season, the NBA reported success across many platforms. Arena capacity was 90.3 percent, its seventh straight year of 90 percent or better. Merchandise sales jumped more than 20 percent and NBA.com saw an increase of more than 140 percent in video views.21

After procuring four years of record attendance through 2008, Major League Baseball had multiple years of attendance declines; however, in the 2011 season, the League was able to overcome a very slow start, endured inclement weather, a slowed economy, and even the influx of high definition TVs to achieve the fifth highest attendance mark ever. A total of 74,859,268 fans attended Major League Baseball games in the 2012 regular season, representing a 1.9 percent increase from 2011. Sports Illustrated writer Tom Verducci noted “baseball is consumed in so many ways that hardly existed, if at all, in its pre-strike popularity era: fantasy leagues, web apps, satellite radio, websites and the plethora of television viewing options on fantastic-looking displays,”22 all impact the game. Attendance remains a vital revenue stream and measure of interest, but now it is part of a much more diverse picture of how baseball is consumed.

Street & Smith’s Sports Business Daily reported that the National Hockey League averaged 17,445 fans per game for the 2012 season, up 1.8 percent from 2011 and up 2.8 percent from 2010. The Canadiens secured the highest league attendance totals including totals that were at 100 percent capacity. A total of 872,193 patrons attended in 2012 equating to a 21,273 per game average.23

Although millions of Americans attend sporting events each year, even more of us watch sports on network and cable television or listen to sports on the radio. For example, the 2014 Super Bowl XLVII featuring the Seattle Seahawks and Denver Broncos was watched by an estimated 111.5 million viewers and had an estimated 26.1 million tweets, exceeding the 2013 numbers where the New York Giants victory over the New England Patriots was watched by more than 111.3 million people. These 2013 and 2014 numbers surpass the 2011 Super Bowl and 1983 finale of “M-A-S-H” to become the most-watched program in U.S. television history.

Today, in the U.S. 290 million people own at least one TV, while worldwide more than 35 percent of consumers own an HD TV. According to Nielsen’s television data collected from 38 key markets around the world (including the host nation China, the United States, Brazil, South Africa, Italy, and Australia), just more than 4.4 billion viewers worldwide – almost 70 percent of the world’s population – watched some part of the 2008 Olympics.24 In fact, an estimated audience of 2 billion watched the Beijing Olympics Opening Ceremony. Viewing levels varied across regions and markets, impacted by factors such as time zone and broadcast time differences. In contrast to the Beijing Summer Olympics, the Sochi Games only drew an average of 21.4 million viewers in primetime. In comparison, NBC’s coverage of the Vancouver Winter Olympic Games drew a total viewing population of 32.6 million, 56 percent female versus 44 percent male. This secured an average audience of roughly three times the size of its nearest rival, Fox, and, according to the Nielsen company in 2012, the coverage held seven of the eight top stops for the week.

During the most recent Summer Olympic Games, Nielsen reported that NBC’s coverage of the London Olympic Games drew more than 219 million American viewers over the span of 5,535 hours of broadcasting. These figures eclipse those of the 2008 Beijing Olympics (also on NBC), which were watched by a mere 215 million American viewers.

ESPN, the original sports-only network launched in 1979, was highlighted by record consumption of ESPN’s core television business in 2011 and 2012. On television and across digital platforms, ESPN was able to secure a series of value-rich agreements with the NFL, NCAA, Wimbledon, Pac-12, and Indy 500. With its long-term and wide-ranging pact with its largest distributor, Comcast, ESPN was able to marry compelling content with evolving technology, i.e., notably the WatchESPN. In addition, they aired a significantly higher number of regular season and college bowl games. The array of ESPN programs serves the sports fan of today on the move in the USA and around the world. ESPN’s results demonstrated that sports fans’ need for the latest and best information – wherever they are – remains unabated. In the most recent survey across ESPN media platforms, which includes all ESPN networks, 113 million people interacted with ESPN during the average week in 2013,25 an average of 675,000 viewers.

However, ESPN is facing more competition than ever. In 2013, ESPN saw a significant decrease in primetime ratings, 32 percent. Competitors such as Fox Sports and NBC Sports are strengthening their position in the marketplace. In addition, broadcasts such as those presented on Golf Channel, NFL Network, Fox Soccer, and NBCSN have experienced increases in viewership.26 According to The Media Audit report (2009), a number of sports events including professional football, baseball, and hockey are on the upswing, and it suggests that while many Americans are uncertain about jobs and the economy, their interest in following sports remains strong.27

Among the report’s findings, 61 percent of U.S. adults regularly follow professional football on radio or TV, a figure that is up from 57.9 percent four years ago. Among professional baseball fans, 51.2 percent regularly follow the sport, compared with 49.5 percent in 2005. Professional ice hockey experienced the most significant increase among sports fans. Among U.S. adults, 22.7 percent frequently follow the sport on TV or radio today, compared with 14.4 percent in 2005. The figure represents a 58 percent increase over four years. The study further reveals that the higher their income, the more likely adults are to follow sports. For example, 71.6 percent of adults earning $100,000 or more in household income regularly follow professional football, a figure that is 18 percent higher when compared with all U.S. adults. Similarly, 61.6 percent of high-income-earning individuals regularly follow professional baseball on TV or radio, a figure that is 20 percent higher than for all U.S. adults. Furthermore, 29.3 percent of affluent adults follow professional ice hockey compared with 22.7 percent of the general U.S. population.

In college sports, the percent of adults who regularly follow college football on radio or TV increased from 44.6 percent in 2005 to 45.9 percent today. However, the same study revealed that while only 22.1 percent of U.S. adults frequently attend college or professional sporting events, the figure remains flat from 22 percent in 2005. Traditional networks are trying to keep pace with the demand for sports programming. The four major networks devote in excess of 2,000 hours to sports programming annually and a family with cable has access to 86,000 hours of sports TV. Sports fees paid by cable, satellite, and telco companies reached 17.2 billion in 2012.28

In addition, according to a Kantar’s Global Sports Media Consumption Report (2013), about 170 million adults (71 percent of the U.S. population) label themselves sports fans, and 97 percent of them watched sports on TV in 2012.29 The majority (97 percent) of these TV sporting events are watched live and therefore the race is on between networks to secure prominent sporting events. In 2011, NBC spent a record $4.38 billion to secure the broadcast and cable rights for the Olympic Games through 2020. NBC extended its stronghold on the Olympics by winning the broadcast rights over rivals Fox and ESPN. Fox bid $3.4 billion for four Games and $1.5 billion for two, while ESPN offered $1.4 billion for two. Add to this deal the NCAA’s $10.8 billion dollar basketball tournament deal, the NCAA conferences multiplying their old deals times four, a $4.4 billion NASCAR deal with NBC, the NHL tripling their previous contract, and the astronomical procurement of the NFL, where networks will provide over $3 billion per year, and you can see the value of sports to the league and the networks.

These numbers show no signs of slowing down in the future. The huge demand for sports broadcasting has led to the introduction of more sport-specific channels. New sports networks such as the Sky Sports F1, College Sports Television (www.cstv.com), Fox Sports 1, Blackbelt TV, the Tennis Channel, and the NFL Network have emerged because of consumer demand. In fact even the WWE is contemplating the release of its own network. Presently, worldwide there are in excess of 300 sport channels. This practice of “narrowcasting,” reaching very specific audiences, seems to be the future of sports media.

Web 1.1 The growth of sports information on the Web

Source: www.espn.go.com.

In addition to traditional sports media, pay-per-view cable television is growing in popularity. Satellite stations, such as DIRECTV, allow spectators to subscribe to a series of sporting events and play a more active role in customizing the programming they want to see. For example, DIRECTV offers NFL Sunday Ticket, Willow Cricket, NASCAR HotPass, NBA League Pass, or the NHL Center Ice to afford consumers instant viewing gratification. Packages such as NHL Center Ice allow subscribers to choose from 40 out-of-market (i.e., not local) regular season NHL games per week for an additional fee.

Employment

Another way to explore the size of the sports industry is to look at the number of people the industry employs. The Sports Market Place Directory, an industry directory, has more than 15,600 listings, 80,000 contact names, and 9 indexes for sports people and organizations.30 A USA Today report estimates that there are upward of 4.5 million sports-related jobs in sales, marketing, entrepreneurship, administration, representation, and media.31 Some estimates range as high as 6 million jobs. In addition to the United States, the United Kingdom employs some 400,000 people in their $6 billion a year sports industry.32 Consider all the jobs that are created because of sports-related activities such as building and staffing a new stadium. Sports jobs are plentiful and include but are not limited to event suppliers, event management and marketing, sports media, sport sales, sports sponsorship, athlete services, sports commissions, sports lawyers, manufacturers and distribution, facilities and facility suppliers, teams, leagues, college athletics, and finance.

The number of people working directly and indirectly in sports will continue to grow as sports marketing grows. Sports marketing creates a diverse workforce from the players who create the competition, to the photographers who shoot the competition (see Appendix A for a discussion of careers in sports marketing).

Global markets

Not only is the sports industry growing in the United States, but it is also growing globally. As the following hyperlink on international sports marketing discusses, the NBA is a premier example of a powerful global sports organization that continues to grow in emerging markets: http://www.nba.com/global/nba_global_regular_season_games_london_mexico_city_2013_06_24.html.

The structure of the sports industry

There are many ways to discuss the structure of the sports industry. We can look at the industry from an organizational perspective. In other words, we can understand some things about the sports industry by studying the different types of organizations that populate the sports industry such as local recreation commissions, national youth sports leagues, intercollegiate athletic programs, professional teams, and sanctioning bodies. These organizations use sports marketing to help them achieve their various organizational goals. For example, agencies such as the United States Olympic Committee (USOC) use marketing to secure the funding necessary to train and enter American athletes into the Olympic Games and Pan American games.

Photo 1.1 Fans in grandstand.

Source: Shutterstock.com.

Figure 1.1 Simplified model of the consumer–supplier relationship in the sports industry

Ad 1.2 Fantasy sports blurring the line between spectator and participant

Source: Sporting News

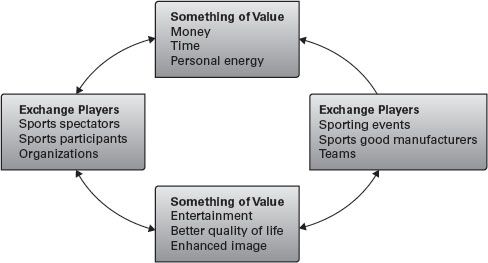

The traditional organizational perspective, however, is not as helpful to potential sports marketers as a consumer perspective. When we examine the structure of the sports industry from a consumer perspective, the complexity of this industry and challenge to sports marketers becomes obvious. Figure 1.1 shows a simplified model of the consumer–supplier relationship. The sports industry consists of three major elements: consumers of sport, the sports products that they consume, and the suppliers of the sports product. In the next sections, we explore each of these elements in greater detail.

The sports industry exists to satisfy the needs of three distinct types of consumers: spectators, participants, and sponsors.

The spectator as consumer

If the sporting event is the heart of the sports industry, then the spectator is the blood that keeps it pumping. Spectators are consumers who derive their benefit from the observation of the event. The sports industry, as we know it, would not exist without spectators. Spectators observe the sporting event in two broad ways: they attend the event, or they experience the event via media chosen media outlet, i.e., radio, television, Internet.

As Figure 1.2 illustrates, there are two broad types of consumers: individual consumers and corporate consumers. Collectively, this creates four distinct consumer groups. Individuals can attend events in person by purchasing single event tickets or series (season) tickets. Not only do individuals attend sporting events, but so too do corporations. Today, stadium luxury boxes and conference rooms are designed specifically with the corporate consumer in mind. Many corporate consumers can purchase special blocks of tickets to sporting events. At times, there may be a tension between the needs of corporate consumers and individual consumers. Many believe that corporate consumers, able to pay large sums of money for their tickets, are pushing out the individual consumer and raising ticket prices.

Both individual spectators and corporations can also watch the event via a media source. The corporate consumer in this case is not purchasing the event for its own viewing, but, rather, acting as an intermediary to bring the spectacle to the end user groups or audience. For example, CBS (the corporate consumer) purchases the right to televise the Masters Golf Tournament. CBS then controls how and when the event is experienced by millions of individual spectators who comprise the television audience.

Historically, the focus of the sports industry and sports marketers was on the spectator attending the event. The needs of the consumer at the event were catered to first, with little emphasis on the viewing or listening audience. Due to the growth of media influence and the power of the corporate consumer, the focus has changed to pleasing the media broadcasting the sporting event to spectators in remote locations. Many season ticket holders are dismayed each year when they discover that the starting time for events has been altered to fit the ESPN schedule. In fact, the recent NFL deals provide networks with the opportunity to interchange delivery schedules across conferences. Because high ratings for broadcasted sporting events translate into breathtaking deals for the rights to collegiate and professional sports, those who present sporting events are increasingly willing to accommodate the needs of the media at the expense of the on-site fan. The money associated with satisfying the needs of the media is breathtaking. For example, in 2011, the NFL agreements secured from the terrestrial networks, FOX, NBC, CBS, and ESPN, combined for a total of $20.4 billion per year. The 2014–2022 totals equate to the same networks paying $39.6 billion per year.33 That number is continuing to grow, as seen in Table 1.2. Identifying and understanding the different types of spectator consumption is a key consideration for sports marketers when designing a marketing strategy.

Figure 1.2 Individual vs corporate consumer

The participant as consumer

In addition to watching sports, more people are becoming active participants in a variety of sports at a variety of competitive levels. Table 1.3 shows “core” participation in sports and fitness activities. As the number of participants grows, the need for sports marketing expertise in these areas also increases.

As you can see, there are two broad classifications of sports participants: those that participate in unorganized sports and those that participate in organized sports.

Table 1.2 NFL media rights

CBS (AFC) |

2014–2022 |

$1.08B |

DirecTV (Sunday Ticket) |

2011–2014 |

$1B |

ESPN (Monday Night) |

2014–2022 |

$1.9B |

FOX (NFC) |

2014–2022 |

$720.3M |

NBC (Sunday Night) |

2014–2022 |

$1.05B |

TOTAL |

$5.75B |

Source: http://espn.go.com/nfl/story/_/id/7353238/nfl-re-ups-tv-pacts-expand-thursday-schedule

Table 1.3 Most popular sports and fitness activities based on core participation (age 6 and above; U.S. residents)

Rank |

Activity |

# Of Participants |

1 |

Walking for Fitness |

114.1 million |

2 |

Bowling |

55.9 million |

3 |

Treadmill |

53.1 million |

4 |

Running/Jogging |

49.4 million |

5 |

Hand Weights |

45.9 million |

6 |

Billiards/Pool |

39.4 million |

7 |

Bicycling |

39.3 million |

8 |

Freshwater Fishing |

38.9 million |

9 |

Weight/Resistance Machines |

38.6 million |

10 |

Dumbells |

37.4 million |

Source: Sports & Fitness Industry Association, www.sfia.org

Unorganized sport participants/organized sport participants

Amateur

Youth recreational instructional

Youth recreational elite

Schools

Intercollegiate

Professional

Minor/secondary

Major

Unorganized sports are the sporting activities people engage in that are not sanctioned or controlled by some external authority. Kids playing a pick-up game of basketball, teenagers skateboarding, or people playing street roller hockey, as well as fitness runners, joggers, and walkers are only a few of the types of sporting activities that millions of people participate in each day. The number of people who participate in unorganized sports is difficult to estimate. We can see how large this market is by looking at the unorganized sport of home fitness. According to a survey published by the National Endowment for the Arts, American households spend $130 annually on sports or exercise equipment. In addition, the average purchase price of a multi-purpose home gym station was $640 while the average cost of a treadmill was $2000.34

We can see that the size of the market for unorganized sports is huge, and there are many opportunities for sports marketers to serve the needs of these consumers.

Organized sporting events refer to sporting competitions that are sanctioned and controlled by an authority such as a league, association, or sanctioning body. There are two types of participants in organized events: amateur and professional.

Amateur sporting events refer to sporting competitions for athletes who do not receive compensation for playing the sport. Amateur competitions include recreational youth sports at the instructional and elite (also known as “select”) levels, high school sports controlled at the state level through leagues, intercollegiate sports (NCAA Division I–III, NAIA, and NJCAA), Olympics, and adult community-based recreational sports. Professional sports are also commonly classified by minor league or major league status.

Sponsors as consumer

Other equally important consumers in sports marketing are the many business organizations that choose to sponsor sports. In sports sponsorship, the consumer (in most cases, a business) is exchanging money or product for the right to associate its name or product with a sporting event, creating a commercial competitive advantage for both parties. The decision to sponsor a sport is complex. The sponsor must not only decide on what sport(s) to sponsor, but must also consider what level of competition (recreational through professional) to sponsor. They must choose whether to sponsor events, teams, leagues, or individual athletes.

Although sponsorship decisions are difficult, sponsorship is growing in popularity for a variety of reasons. As Pope discusses in his excellent review of current sponsorship thought and practices,35 sponsorship can help achieve corporate objectives (e.g., public awareness, corporate image building, and community involvement), marketing objectives (e.g., reaching target markets, brand positioning, and increasing sales), media objectives (e.g., generate awareness, enhance ad campaigns, and generate publicity), and personal objectives (management interest). According to IEG, lingering effects of scattered economic crises throughout the world and a yet-to-stabilize recovery in the U.S. have impeded sponsorship spending worldwide. However, despite these adverse impacts, a growth of 4.1 percent globally and 4.5 percent in North America was estimated in 2014. Sponsorship spending continued to reach a new plateau, $20.6 billion being spent in the U.S. and an estimated $55.3 billion worldwide. Projections for future growth are highly dependent upon the unprecedented recognition at the highest levels of corporations that sponsorship is a potent answer to the challenge of how to build attention, support, and loyalty for brands in an environment that is otherwise hostile to marketing communications.36

Perhaps the most difficult conceptual issue for sports marketers is trying to understand the nature of the sports product. Just what is the sports product that participants, spectators, and sponsors consume? A sports product is a good, a service, or any combination of the two that is designed to provide benefits to a sports spectator, participant, or sponsor.

Goods and services

Goods are defined as tangible, physical products that offer benefits to consumers. Sporting goods include equipment, apparel, and shoes. We expect sporting goods retailers to sell tangible products such as tennis balls, racquets, hockey equipment, exercise equipment, and so on. By contrast, services are defined as intangible, nonphysical products. A competitive sporting event (i.e., the game itself) and an ice-skating lesson are examples of sport services.

Sports marketers sell their products based on the benefits the products offer to consumers. In fact, products can be described as “bundles of benefits.” Whether as participants, spectators, or sponsors, sports products are purchased based on the benefits consumers derive. Ski Industry America, a trade association interested in marketing the sport of snowshoeing, understands the benefit idea and suggests that the benefits offered to sports participants by this sports product include great exercise, little athletic skill, and low cost (compared with skiing). It is no wonder snowshoeing has recently emerged as one of the nation’s fastest growing winter sports.37

Spectators are also purchasing benefits when they attend or watch sporting events. For example, the 2014 Super Bowl was the most watched event in U.S. television history, attracting 111.5 million viewers. The game provides consumers with benefits such as entertainment, ability to socialize, and feelings of identification with their country’s teams and athletes.

Moreover, organizations such as Federal Express, which paid $205 million over 27 years for the naming rights to the Washington Redskins sports complex that opened in 1999, believe the association with sports and the subsequent benefits will be worth far more than the investment.38 The benefits that organizations receive from naming rights include enhanced image, increased awareness, and increased sales of their products.

Chris Ferris, Associate Athletic Director for Marketing & Promotions University of Pittsburgh

Mr. Ferris joined the Pittsburgh Athletic Department in 1994 when he served as a student equipment manager. The following year, he worked as an undergraduate intern with the media relations and marketing departments. He is also a 1998 graduate of Pittsburgh with a Bachelor’s degree in business and communications and earned his Master’s Degree at the University of Pittsburgh’s Katz Graduate School of Business.

1. What is your career background? How did you get to where you are today? I started in athletics as a football equipment manager. Afterwards, I volunteered and interned with both the Media Relations and Marketing Departments. Volunteering and interning were key. The opportunities allowed me to learn about the industry, meet some terrific people, and give people in our organization see me work. Once given my first opportunity as assistant director of marketing, I continued to work as enthusiastically as possible while continuing to volunteer for any additional projects within the department. Once again, this enabled me to grow as a professional.

2. What is your role as Associate A.D. for Marketing & Promotions? Our marketing department and Pitt manages and oversees:

a. Licensing and merchandising

b. Advertising and ticket sales

c. Corporate ticket sales, group ticket sales, and promotions

d. Game presentation

e. Internet services

f. PantherVision production

g. Pitt Panthers television Additionally, I work very closely with our multi-media rights holder and our ticket operations team

3. Why did you choose the University of Pittsburgh, for both academic as well as your career path? The University of Pittsburgh is an amazing place. Our leadership at the University and in our Athletic department are both committed to being the best and providing the best experience for our students and student-athletes. I believe in our leaders and people and I believe in our leaders and professions.

4. What made you get into marketing? What do you like about it best? Volunteering and interning exposed me to many different areas of Intercollegiate Athletics. Marketing gives me an opportunity to work with people both internally within the university and externally. I really enjoyed having what I believe is the best of both worlds; dealing with students, faculty, and staff while also having the opportunity to work with external sponsors and partners.

5. How large is your full-time marketing staff? Seven people.

6. What are the main marketing challenges facing Pitt Athletics? These can be sport specific. Our goals are to sell-out all of our venues for all of our teams.

7. What is your ultimate goal for your career? First, make positive impacts on our teams, coaches, and fans. Second, serve as an athletic director.

Different types of sports products

Sports products can be classified into four categories. These include sporting events, sporting goods, sports training, and sports information. Let us take a more in-depth look at each of these sports products.

Sporting events

The primary or core product of the sports industry is the sporting event. By primary product we are referring to the competition, which is needed to produce all the related products in the sports industry. Without the game there would be no licensed merchandise, collectibles, stadium concessions, and so on. You may have thought of sports marketing as being important for only professional sporting events, but, as is evident by the increased number of media outlets and broadcasts, the marketing of collegiate sporting events and even high school sporting events is becoming more common.

Historically, a large distinction was made between amateur and professional sporting events. Today, that line is becoming more blurred. For example, the Olympic Games, once considered the bastion of amateur sports, is now allowing professional athletes to participate for their countries. Most notably, the rosters of the Dream Teams of U.S. Basketball fame and the U.S. Hockey team are almost exclusively professional athletes. This has been met with some criticism. Critics say that they would rather give the true amateur athletes their chance to “go for the gold.”

Athletes

Athletes are participants who engage in organized training to develop skills in particular sports. Athletes who perform in competition or exhibitions can also be thought of as sports products. David Beckham, Chamique Holdsclaw, and Phil Mickelson are thought of as “bundles of benefits” that can satisfy consumers of sport both on and off the court.

One athlete to achieve this “superproduct” status is the multimillion dollar phenomenon named Eldrick “Tiger” Woods. Tiger seemed to have it all. He was handsome, charming, young, multiethnic, and most important – talented. Tiger’s sponsors certainly think he was worth the money. However, poor choices and inappropriate behavior attracted controversy. Controversy has required the likes of Nike, Buick, NetJets, and American Express to rethink their level of affiliation, impacting Tiger’s multimillion dollar sponsorship deals.

Sports marketers must realize that the “bundle of benefits” that accompanies an athlete varies from person to person and has affiliated risk. The benefits associated with Allen Iverson are different from those associated with Kevin Garnett or golfer Michelle Wei. Regardless of the nature of the benefits, today’s athletes are not thinking of themselves as athletes but as entertainers.

A final sports product that is associated with the sporting event is the site of the event – typically an arena or stadium. Today, the stadium is much more than a place to go watch the game. It is an entertainment complex that may include restaurants, bars, picnic areas, and luxury boxes. Today’s teams are not only trying to create more visually appealing buildings, but they’re interested in making attending the game an all-encompassing entertainment experience. In fact, stadium seating is becoming a “product” of its own.

For example, some of the following changes already seen at today’s venues will soon become the norm. Things such as free Wi-Fi, mobile apps, fantasy stats on video boards, TVs in seats and bathrooms, customizable instant replays, bars overlooking fields, holograms on the fields instead of players, and improved access are the wave of the future. Companies like Cisco offer Stadium Wi-Fi packages made specifically for sports arenas that have an immense amount of internet usage in a confined area. Cisco plans on placing antennas in specific places in the stadium for optimal performance for people to use their smart phones with optimal speeds.39

In another example, it might seem like a stretch to think that a roller coaster will pop up over a baseball field’s outfield fence, but some type of amusement park ride – Detroit’s Comerica Park already has a Ferris wheel – that provides unique views of the game (and can keep the kids entertained) seems inevitable.40

Sporting goods

Sporting goods represent tangible products that are manufactured, distributed, and marketed within the sports industry. The sporting goods and recreation industry was a $79.1 billion industry in 2013.41 The segments and their relative contribution to the industry sales figure include sports equipment ($21.5 billion), exercise equipment ($4.7 billion), sports apparel ($31.8 billion), athletic footwear ($13.6 billion), and licensed merchandise ($7.5 billion). The largest product category, in terms of sales, was firearms and hunting (10 percent), industrial exercise equipment (9 percent), running footwear (6 percent), and fishing (5 percent).42 Although sporting goods are usually thought of as sports equipment, apparel, and shoes, there are a number of other goods that exist for consumers of sport. Sporting goods also include licensed merchandise, collectibles, and memorabilia.

Licensed merchandise

Another type of sporting goods that is growing in sales is licensed merchandise. Licensing is a practice whereby a sports marketer contracts with other companies to use a brand name, logo, symbol, or characters. In this case, the brand name may be a professional sports franchise, college sports franchise, or a sporting event. Licensed sports products usually are some form of apparel such as team hats, jackets, or jerseys. Licensed sports apparel accounts for 60 percent of all sales. Other licensed sports products such as novelties, sports memorabilia, trading cards, and even home goods are also popular.

The Licensing Letter reports that sales of all licensed sports products reached $17.5 billion worldwide in 2012. In fact, sport licensing generates $800–900 million in royalty revenue annually. Growth is expected to continue based on research from the National Sporting Goods Manufacturers Association and the Sports Licensing Report. U.S. retail sales of licensed products for the four major professional sports leagues (NBA, NFL, MLB, and NHL) has more than doubled since the 1990s, from $5.35 billion in 1990 to $13.5 billion in 2012.43

Through this period, the various major professional sports leagues developed a sprawling network of licensing arrangements with more than 600 companies. Another 2,000 companies have arrangements with the various college and university licensing groups. As far as the retail distribution of product, a network of “fan shops” grew to more than 450 in number and licensed products found their way into sporting goods stores, department stores, and eventually, the mass merchants. To compete, most of the major sporting goods chains and many department stores developed separate areas devoted exclusively to licensed goods.44 Sales of licensed sports products will continue to grow as other “big league” sports gain popularity. For example, NASCAR has seen the sale of licensed goods increase from $60 million in 1990 to $500 million in 1994 and to an estimated $1.2 billion in 2013 (see NASCAR.com).

Collectibles and memorabilia

One of the earliest examples of sports marketing can be traced to the 1880s when baseball cards were introduced. Consider life before the automobile and the television. For most baseball fans, the player’s picture on the card may have been the only chance to see that player. Interestingly, the cards were featured as a promotion in cigarette packages rather than bubble gum. Can you imagine the ethical backlash that this practice would have produced today?

Although the sports trading card industry reached $1.2 billion in 1991, industry wide yearly sales plummeted to $700 million in 1995 and are now stable at between $400 and $500 million.45 What caused this collapse? One answer is too much competition. David Leibowitz, an industry analyst, commented that “With the channel of distribution backed up and with too much inventory, it was hard to sustain prices, let alone have them continue to rise.” At the beginning of the 1980s there were only a few major card companies (Topps, Donruss, and Fleer) but by the early ’90s there were sets of cards produced by six different companies, more in the market than ever before. This flooded market and the cartoon fad cards have hurt the sports trading card industry. Other problems include labor problems in sports, escalating card prices, and kids with competing interests.

Photo 1.2 The sports collector’s dream – the Baseball Hall of Fame. The Baseball Hall of Fame’s plaque gallery, housing plaques for all Hall of Famers, November 26, 2011 in Cooperstown, NY.

Source: Shutterstock.com

There is, however, some evidence that the industry will rebound. Citing a glut in the marketplace and the desire to regain some control over the baseball card industry, Major League Baseball declined to renew Donruss’ license, leaving Topps and Upper Deck as the only producers. Perhaps the biggest boost will be selling and trading cards on the Internet.46 The first major company in this market was the industry leader, Topps. Each week on etopps.com the company promotes three new limited edition cards or IPOs (Initial Player Offerings). The buyer can then purchase the card and takes physical possession, sell the card in an auction, or hold the card until it appreciates in value. The new product has been a huge success for Topps and could be the future of the card industry.

Personal training for sports

Another growing category of sports is referred to as personal training. According to the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), employment opportunities for fitness workers are expected to increase more than 29 percent over the 2008 to 2018 decade.47 Much of this growth is attributed to increasing awareness of the health benefits of regular exercise. However, these products are produced to benefit participants in sports at all levels and include fitness centers, health services, sports camps, and instruction.

Fitness centers and health services

When the New York Athletic Club was opened in 1886, it became the first facility opened specifically for athletic training. From its humble beginning in New York, the fitness industry has seen an incredible boom. “Pumping iron” was a common phrase in the 1970s and early 1980s. Moreover, the 1970s aerobics craze started by Dr. Ken Cooper added to the growth of health clubs across the United States.

It is no secret that a physically fit body is becoming more important to society. The growth of the fitness industry follows a national trend for people to care more about their health. In 1993, there were 11,655 clubs in the United States billed as “health and fitness” centers. In 2012, this number had grown to a record high of 29,960 clubs. Moreover, health club membership climbed to a record high 51.4 million people.48 Why are people joining health clubs in record numbers? According to a study conducted by the International Health, Racquet, and Sportsclub Association, the factors that will continue to support the growth of health club membership in the United States include the following:

1. The growing number of health clubs that make it more convenient for consumers.

2. The continued and increased promotion of the benefits of exercise by organizations like the U.S. Surgeon General.

3. More Americans are concerned about the adverse effects of poor exercise and eating habits.49

Sports camps are organized training sessions designed to provide instruction in a specific sport (e.g., basketball or soccer). Camps are usually associated with instructing children; however, the “fantasy sports camp” for aging athletes has received considerable attention in the past few years. Fantasy sports camps typically feature current or ex-professional athletes, and the focus is more on having fun than actual instruction. Nearly every major league baseball team now offers some type of fantasy camp for adults. For example, Chicago White Sox Fantasy Baseball Camp allows you (if you’re over 21 years old) to be a major leaguer for a week. The experience consists of social activities, games, and instruction with former major league players, but this does not come cheap. The price for participating is roughly $4,200 per person.

Along with camps, another lucrative sports service is providing personal or group instruction in sports. The difference between instruction and camps is the ongoing nature of the instruction versus the finite period and intense experience of the camp. For example, taking golf or tennis lessons from a professional typically involves a series of half-hour lessons over the course of months or sometimes years. Contrast this with the camp that provides intense instruction over a week-long period.

Sports information

The final type of sports product that we discuss is sports information. Sports information products provide consumers with news, statistics, schedules, and stories about sports. In addition, sports information can provide participants with instructional materials. Sports-specific newspapers (e.g., The Sporting News), magazines (e.g., Sports Illustrated), Internet sites (e.g., cnnsi.com), television (e.g., The Golf Channel), and radio (e.g., WFAN) can all be considered sports information products. All these forms of media are experiencing growth both in terms of products and audience. Consider the following examples of new sports information media. ESPN launched its new magazine in March 1998 to compete with Sports Illustrated, which leads all sports magazines with a circulation of more than 3.2 million. The current circulation for ESPN The Magazine is 2.1 million, but all indications are that there is room at the top for two sports magazine powerhouses.50

The fastest growing source of sports information is on the World Wide Web, through use of computers, tablets, and smartphones. A look at the top sports Web sites is shown in Figure 1.3. Today, consumers are more connected than ever, with more access and deeper engagement, thanks to the proliferation of devices and platforms. The playing field for the distribution of sports content has never been deeper or wider. In fact, social media exchanges are now standard practice in our daily lives. Not only do consumers have more devices to choose from, but they own more devices than ever. Connected devices such as smartphones and tablets have become constant companions to consumers on the go and in the home. The rapid adoption of second screen alternatives has revolutionized shopping and viewing experiences. Sports-related content publishers and advertisers seeking to reach sports enthusiasts have more options than ever to connect with fans as they consume all things sports. Case in point: it’s likely that at least one billion sports fans worldwide viewed events, got updates, and checked results of the 2012 London Olympics on digital devices, including PCs, mobile phones, and tablets.51

A study conducted by Burstmedia (2012) revealed sports fans use tablets and/or smartphones to access online sports-related content while engaged in a number of activities, ranging from watching sports content on television (35.7 percent) to browsing web content on a desktop/laptop computer (19.4 percent), and/or attending a live sporting event in person (7.4 percent).52 Tablets and smartphones are emerging as sports content consumption platforms. The study revealed that among all sports fans, 31.6 percent use tablets (e.g., an iPad) and 42.9 percent use smartphones (e.g., an iPhone) to access online sports content and video at least occasionally. In addition, 17.1 percent use tablets and 23.8 percent use smartphones to watch a live sporting event or game. Furthermore, Nielsen’s 2011 study on consumer usage identified 31 percent of tablet and smartphone users who downloaded an app in the past 30 days, downloaded a sports-related app.53 Sports fans have been leading the charge and finding new ways to share information and socialize, using the Web as a daily source of information. Due to the tremendous amount of information that sports fans desire (e.g., team stats, player stats, and league stats) and the ability of the Web to supply such information, Web portals and sports marketing make a perfect fit. Sports fans are the biggest consumers of media via cross-platform devices. According to ESPN’s Glenn Enoch, sport consumers have an urgent need to stay connected to sports all day, whether it is game-casting or managing fantasy leagues, or just keeping up with headlines; that’s what makes sports fans different, the demand to access information.54 One example of the success of providing sports information via the World Wide Web is www.ESPN.com (ESPN’s Web site).

Figure 1.3 Top sports Web sites

Source: Adapted from: http://www.ebizmba.com/articles/sports-websites. Please note this is a snapshot of the current information at the time.

Web 1.2 Ski.com provides information for ski enthusiasts

Source: Courtesy ski.com

ESPN’s multilayered Web portal affords consumer access and tracks consumer behavior across the growing list of media and Web platforms. According to Julie Roper, ESPN Director of Advertising Analytics, “It used to be just about high ratings and reach, and that was enough, now, there’s a lot more accountability, so we have gotten much more granular.” Considering the global nature of sport, looking across the multiplatform universe is essential. That is why ESPN developed the following seven cross media principles to further solidify and integrate multimedia and Web platform usage and analysis.

ESPN’s seven cross-media principles

1. New media create new strata of users: When a technology is introduced, some will adopt it but most do not. There is no foreseeable future when every person has and uses every available device.

2. No new metrics: Measuring new media does not require new metrics – it requires metrics that unite behavior across different platforms. They may be called different things in different media, but they have the same meaning: How many, how often and how long.

3. Users and usage: “How many” is not the same as “How long.” Both users and usage are valuable metrics in analyzing cross-media behavior, but mean different things and must be considered separately.

4. A heavy user is a heavy user: The heavier user of one medium tends to be a heavier user of other media as well.

5. Cross-media usage is not zero-sum: Doing one behavior more does not mean doing another behavior less. Media usage is no longer constrained to limited locations and opportunities – people can consume media throughout the day, wherever they are. We call this “new markets of time.” TV viewing continues to grow because the media pie is getting larger.