Making the Magic Happen

Memes, memory, and sticky lines

Some ads take hold and won’t let go.

In the last lesson we explained how to create good, strong copy. In this companion lesson we look at how to add memorability to your messages. As we’ve said, the two lessons work together to cover the basics and beyond.

We’ll begin with an anecdote from the distant past, and that means switching to the first person as Roger takes the writing reins.

It’s the early seventies. A small boy (Rog) and his even smaller brother (Tim) are sitting in front of the family’s recently acquired color telly enjoying pre-dinner cartoons. The ads come on and suddenly we’re confronted by a group of colorful metallic robot-type creatures sitting round a table in what must surely be a spaceship. That got our attention. Then the metalheads start to speak and it just gets better.

Martian One (some sort of leader): “On your last trip, did you discover what the Earth people eat?”

Martian Two (some sort of explorer): “They eat a great many of these.” [Holds up a potato in his unfeasibly crude claw. The other Martians immediately start chattering among themselves.]

“They peel them with their metal knives...” [Chattering steps up a pace.]

“...boil them for 20 of their minutes...” [Metallic laughter begins to displace the chattering.]

“...then they smash them all to bits.” [Martians overcome with laughter.]

Martian One: “They are clearly a most primitive people.” [Whole group collapse into fits of laughter, some rolling around and waving their arms in the air.]

Slogan (sung): “For mash, get Smash.”

We thought we’d died and gone to heaven. Remember, this is just a few years after the first moon landing, and all things space/UFO/alien-related were big news in our playground.

Now, impressive though the Martians were, it wasn’t these crudely animated aliens that really made us chuckle; it was their dialogue. I can repeat the script even now (in fact I wrote most of the above from memory). We chanted it, repeated it, reveled in it. Our parents’ refusal to put us up for adoption after hearing “They are clearly a most primitive people HAHAHA” for the thousandth time as they struggled to get dinner ready is a testament to their patience and parenting skills. Even more remarkable is why these words have stuck with me for so many years. But stuck they have.

The Sugar Puffs Honey Monster, another of John Webster’s cool creations.

Although this little tale is intensely personal, it’s also universal; we all have similar stories featuring lines of copy we picked up in our past and carry around with us as part of who we are. Taken from print and TV ads, packaging, posters, and public information films, they’ve stuck with us—stuck to us—as some of our most persistent memories. They are sticky lines, and they are the subject of this lesson.

What is this “sticky” of which we speak?

Let’s properly define “sticky lines,” a phrase borrowed from the online world, where it is used to refer to compelling content intended to keep a user glued to a particular website.

For our purposes a “sticky line” is any headline, slogan, tagline, and so on that lodges in its audience’s brains and refuses to budge. Sticky lines tend to appear at the top or bottom of a piece of communication, although the principles explained here work equally well for any compressed text in any location—captions, conclusions, summaries, e-mail subject lines, etc.

Copy that achieves sticky status tends to exhibit certain qualities. These have been understood— with varying degrees of clarity and with changing emphasis—for many years. As proof let’s go back to 1955; “Rock Around the Clock” has just been released, the first Disneyland has recently opened in California, and a new board game called Scrabble is proving quite a success. In the US an advertising executive called Charles Whittier has published a book called Creative Advertising. In it he defines a slogan as:

...a statement of such merit about a product or service that it is worthy of continuous repetition in advertising, is worthwhile for the public to remember, and is phrased in such a way that the public is likely to remember it.

In other words a slogan (or in our case, a sticky line) is worth repeating, worth remembering, and—crucially— is written in a way that makes it memorable.

Now whizz forward 50 years to the new millennium. UK adman Dave Trott had this to say in an article for the UK’s Campaign magazine:

“A slogan is there to deliver a USP or branding. If you love my commercial you shouldn’t be able to describe it to anyone else without mentioning the name of the product and the slogan.”

In other words a sticky line should be integral to a piece of communication and not stuck on as an ear-pleasing afterthought. In the same article Andrew Cracknell, executive creative director for a veritable alphabet soup of international advertising agencies including FCB, WCRS, and APL, adds:

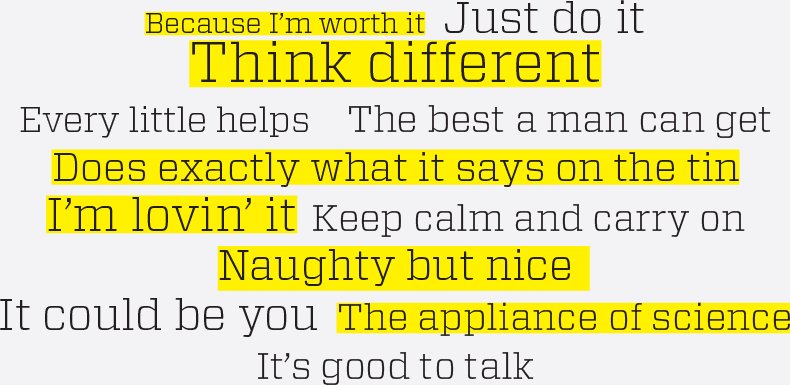

Ear-catching language in action.

The ones that stick out tend to be written in the public language. There has to be rhythm or a rhyme or a quirkiness in the line that catches the ear.

“Catching the ear”—that’s stickiness in three words. The examples Cracknell offers are “It’s a lot less bovver than a hover,” “Vorsprung durch Technik,” and “Beanz Meanz Heinz”—all of which do indeed show plenty of rhythm, rhyme, and quirk. We could add Nike’s “Just do it,” Bic Lighter’s “Flick your Bic,” Ford’s “Everything we do is driven by you,” and eBay’s “Buy it. Sell it. Love it.’

Having outlined the qualities of a sticky line in broad terms, let’s look at memorability in more detail.

Memes mean Heinz

Sorry, we couldn’t resist that. Allow us to explain. In his groundbreaking book The Selfish Gene, Oxford University biologist Richard Dawkins introduced the world to a powerful new idea: the meme (rhymes with “seem,” as if you didn’t know).

A meme, Dawkins wrote, is much like its biological cousin the gene. Like a gene, a meme is a selfreplicating unit of information. However, memes don’t replicate biologically; instead they’re passed around in the form of ideas. Dawkins described memes as the “basic unit of cultural transmission.” He notes:

“Just as genes propagate themselves by moving from body to body via sperm or eggs, so memes propagate themselves by moving from brain to brain via culture.”

Let’s have some examples. Presumably at some point in your life you’ve had a song going round and round in your head for hours on end, driving you slowly insane? That tune is a meme in action. Or you’ve heard a catchphrase on a comedy show and found yourself unconsciously using it? Another meme. It’s the same with any fashion, idea, or image that finds its way into our collective consciousness and spreads like wildfire. Very crudely, we could say a meme is any cultural expression that suddenly seems to be everywhere.

These examples illustrate why the much-maligned meme is sometimes called an idea virus (or in the case of music, an ear worm). Much work has been done mapping the spread of memes in culture, and the dynamic they follow is indeed that of contagion. Like real viruses, memes are self-perpetuating and almost impossible to eradicate. It’s no exaggeration to say cultures catch memes in much the same way populations catch colds.

Given their infectious quality it’s not surprising that memes are at the heart of what has become known— appropriately enough—as “viral marketing,” a loose collection of techniques designed to piggyback on existing social relationships or networks to sell or promote something. The classic form is word-of-mouth recommendation—either face-to-face or online—but any easily shareable content does much the same job.

Viral has become a crucial part of marketing practice, and underpins such wildly successful ad campaigns as Burger King’s “Subservient Chicken,” Cadbury’s “Drumming Gorilla,” and Old Spice’s remarkable “The Man Your Man Could Smell Like.” The latter attracted almost 7 million YouTube views in just 24 hours, rising to 23 million views in just 36 hours. Needless to say, all three owe a good dollop of their success to their memelike nature. In fact it shouldn’t be called viral marketing at all—it’s meme marketing, pure and simple.

Blackpool’s rather incredible Comedy Carpet. Created by artist Gordon Young and designed by Why Not Associates, this typographic tour de force contains 160,000 precisely cut granite letters embedded in concrete, spelling out the jokes and catchphrases of over 1,000 of the UK’s best-loved entertainers. The result is 23,000 square feet of comedy memes.

Hopefully you can see how relevant memes are to the subject of stickiness. Robin Wight—the W in ad agency WCRS and a colorful creative like they just don’t make any more—is a big fan of memes. He told us:

“As copywriters we’re basically meme men. We want to infect people’s brains with our brands, and things that have got some memetic quality are more easily caught by the brain. Memes are memory devices that help spread words from brain to brain.”

All of which reinforces what we said earlier: If you want your ideas to spread and stick, make them meme-y.

Now, important though memes are, the last pages simply make explicit something that good copywriters have understood instinctively for decades—that certain ideas, expressed in certain ways, have dramatically more sticking power than others. And it’s to those “certain ideas” and “certain ways” that we now turn.

Twelve ad slogans that have entered everyday language in the UK—perhaps the ultimate form of stickiness.

To become truly sticky, a piece of copy needs to be simple, it needs to give pleasure, and it needs to be easily passed on. If a potential meme/sticky line isn’t instantly intelligible then the chances are it won’t catch its audience’s ear. If it doesn’t provide a moment of enjoyment then there’s no motivation for someone to make the meme their own or share it with others, and if it isn’t easily transferable—either in speech, writing, or via a social network—then it’s destined for a short, obscure life.

What follows is a toolbox of techniques intended to help you make your messages simple, pleasurable, and transferable. Refer to them when you’re next stuck for a bit of stickiness—they don’t tell you what to say (how could they?), but they do tell you some proven ways to say it.

Create an emotional connection

Sticky writing touches the reader. This connection comes from making it personal. In fact a prime way to make a line sticky is to help readers see themselves in it. According to Robin Wight:

The way to get me to read 5,000 words of copy is to have a headline all about Robin Wight. The more you can make an ad personally relevant to its reader, the more chance you have of getting through.

Say it strange

Why did Apple say “Think different” and not “Think differently”? Why did they follow it with “The funnest iPod ever” rather than something like “The most enjoyable iPod we’ve ever made”? Why does Aleksandr the meerkat—spokesanimal for price-comparison website comparethemarket.com—say “Simples” and not “Simple”? Why did 7UP promote itself as “The Uncola”? Why did Budweiser decide “Whasssup?” was the perfect way to build their brand? We’ll tell you why: They’re all examples of a linguistic quirk used to create a mighty meme. By twisting language just a bit they achieved maximum memorability. It’s a powerful technique but be warned, it’s easy to get wrong.

Aleksandr says “Simples.”

Budman says “Whassup!”

Jaunty copy that highlights a fact many of us would rather not acknowledge: Our lives are less interesting than a squirrel’s.

The brand managers for Birds Eye Potato Waffles clearly felt they could do the same with their slogan “They’re waffly versatile.” The result is truly waffle.

Tell them something they don’t know

A good way to create stickiness is to offer your reader relevant, thought-provoking information. Ogilvy’s classic ad that begins “At 60 miles an hour the loudest noise in this new Rolls-Royce comes from the electric clock” is a marvelous example (see overleaf), as he went on to support this imagination-grabbing headline with a slew of interesting info-nuggets.

Ogilvy’s ad ran way back in 1958, yet its approach is entirely usable today. In recent years Roger used the same “give ’em something interesting to think about” technique in a brochure for ultra-high-end cell phone brand Vertu, listing 55 rock-solid reasons to believe the hype.

Tell them a story

We cover this in more detail in Lesson Six, but the important thing to know is good stories hold people’s attention in a way little else can. We don’t mean “Once upon a time”; we mean any narrative that creates a sense of involvement and identification. If readers can project themselves into your story then the chances are they’ll stay with you to the end and remember what you said.

Have something to say

In his book The Craft of Copywriting, UK adman Alastair Crompton points out that there are only two kinds of ad: those with something to say and, er, those that don’t. Sticky ads—and indeed sticky texts of all descriptions —are very much the former. If you’ve got something intelligent, beneficial, or interesting to say about your product, service, or brand then for God’s sake say it. You’d be amazed how many organizations clog their communications with irrelevant puffery instead of emphasizing their real point of difference. And don’t bury what you’ve got to say in your body copy—get it up top in the headline or lead paragraph. Now is not the time for modesty.

It’s recently come to light that Ogilvy borrowed this classic “prove it” headline almost word for word from a 1933 ad for Pierce-Arrow cars.

For winemaker Primi Piatti, every bottle tells a story.

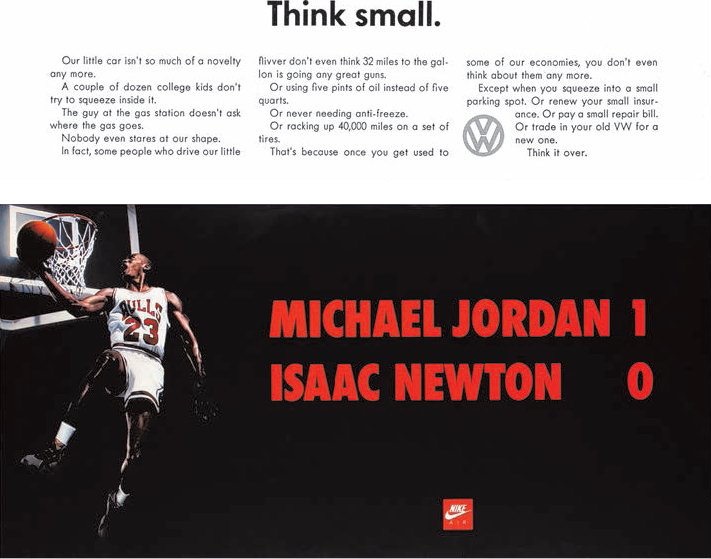

“Beetles aren’t big”—not the most profound observation ever made, but enough to kick-start one of advertising’s all-time top campaigns.

What a comparison. So wrong, yet so utterly right.

Two lovely “compare and contrast” ads for Pedigree Bitter. The tone is pure pub banter.

There’s an appealing restraint to this that gives the selling point a sugar coating.

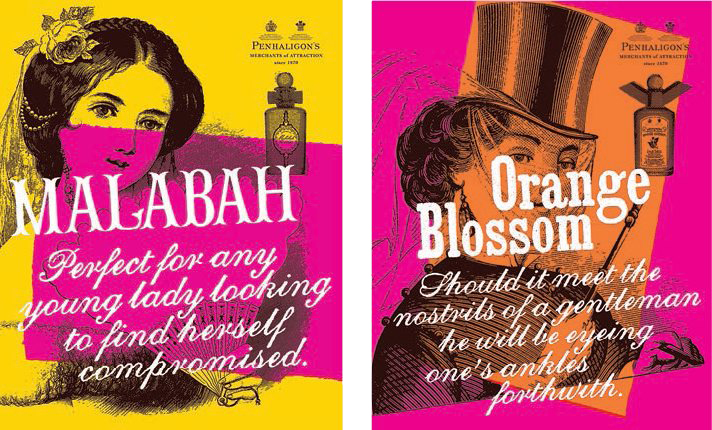

Three examples of product as benefit from Penhaligon. The ad on the left here is a classy take on the classic angle that aftershave makes its wearer more attractive.

A different approach to proving it. Not a number in sight, but this digital before-andafter promo piece for a freelance proofreader is equally effective.

Bear in mind your message doesn’t need to be that insightful, it just needs to act as the foundation for the rest of your argument. As Dave Trott puts it:

Think of an oyster. You start out with a piece of grit, and build a pearl around it. People buy the pearl, not the grit. But no grit, no pearl.

Compare and contrast

Seven-stone weakling into hard-bodied he-man. Filth-stained frock into dazzling dress. Smoker’s teeth into sparkling incisors. You get the idea—it’s before and after, and it works. It may sound a tired technique, but it’s as tired as you make it. There’s always a fresh angle when it comes to dramatizing the benefit, and it’s your job to find it. Faster, slower, bigger, smaller, reassuringly expensive, remarkably cheap—the list goes on. To be effective and to avoid accusations of cynicism you need to compare like with like and only draw conclusions that can be justified. Do that and you’re only doing what any sensible purchaser does when sizing up a product or service, so why not help them on their way?

A brilliant combination of design and copy that graphically illustrates how widescreen gives you more.

Leaving aside the distinct possibility of driver distraction and ensuing highway mayhem, this text makes its point—that if you can read this you must be stuck in traffic— with wit and intelligence.

Prove it

One of the all-time top techniques for creating stickiness. If possible, explain the benefit of your product or service using specific numbers. If you’ve picked the right angle, and your figures are sufficiently impressive, then stickiness will ensue. The other way to say this is, “Don’t claim, demonstrate” (or if you prefer, “facts persuade”). In each case the sentiment is the same: provide objective proof to substantiate what you’re saying and you’ll get through to people.

You’ve been asked to write an in-box leaflet for some new running shoes. Most folks who buy them will jog around their local park, perspiring lightly while trying to look cool. But you don’t write this. While doing the detailed research we recommended in the last lesson you discover this particular sneaker is favored by some ultramarathon madman who achieves distances normally associated with airliners. That’s what you write about. The unstated message is: If this shoe works for him, just think what it’ll do for you. So try describing your subject overcoming the toughest challenge imaginable—the so-called torture test. That should create a bit of stick.

Pure “slice of life” copy for one of the UK’s biggest coffee chains. Every nod or smile of recognition adds to its stickiness. Note the lovely change of pace in the final sentence as the caffeine kicks in.

Translation: “This car works when it’s virtually submerged, so think how it’ll perform on dry land.”

Don’t do it. Stop now before you get the bug. Go find yourself a proper job. I say this entirely seriously (also selfishly—there’s enough competition out there already and the last thing I need are more people trying to steal my work).

Write quickly. There will be plenty of time to revise and rewrite later. Try to invest your work with energy.

Aldous Huxley wrote something to the effect that mankind will not be defeated by the tyranny of any government but instead will invent ways to distract itself to death. Huxley was anticipating the Internet and its hideous ability to sabotage your carefully structured working day. If you want to write, log off.

Love your first draft but don’t love it too much. Even if it’s perfect the powers that be will demand rewrites because they can, so practice holding some stuffback. Remember, it’s not so much about writing as rewriting. The sooner you understand this, the better.

Learn to cut your own stuff. I guarantee you will be asked (or ordered) to cut lines that you adore. So learn to self-cut. In the long run it’s less painful.

It’s an unhealthy and lonely vocation so try to get up and walk about a bit or go for a run. Better still, try going for a walk or a run with another writer. You can moan to each other.

Read other writers’ work. That’s the best way to learn about writing.

Take notes. People say great, unscripted things all the time. Use them.

You will constantly be asked “What else have you got?,” so it helps to have an answer. Learn to juggle. Keep multiple balls in the air. Spin many plates. Always have a fall-back. Don’t put all your eggs in one basket. Oh, and avoid clichés.

Steal a bit but not too much. Try to learn the difference between a clever new take on something and a blatant rip-off.

Ignore most advice given to you by other writers. We are a savage and bitter breed who love the sound of our own voices and delight in the misery of others.

Stephen Leslie worked as a script reader, tea maker, cameraman, producer, and director. He started out as a script reader for Sally Potter, John Schlesinger, and Jon Amiel. He then wrote and directed an award-winning short film about bestiality and royalty called I Was Catherine the Great’s Stable Boy. This helped win him a place on the BBC’s Trainee Assistant Producer scheme, after which he spent four years directing documentaries for the BBC. For the last ten years he has focused almost exclusively on scriptwriting, with commissions from the BBC, Film4, Working Title, Revolution, and Qwerty. Back in 2007 he was (perhaps prematurely) named a Screen International “Star of Tomorrow.”

Concrete, tangible ideas tend to engage readers more readily than their abstract, intangible equivalents—it’s just easier for the casual reader to see what’s in it for them. Most modern business-speak falls into this trap, with “core competencies” instead of “skills” and “proactive strategies” rather than “plans.” As the business writer John Simmons puts it, “Language that speaks of real people doing real things creates images that lodge more deeply and stay longer in our memories,” which is a nice way of describing stickiness.

How to check for stickiness

The only real test of stickiness is the extent to which a line embeds itself in the minds of its audience. Nevertheless, here are a few questions you can use to make sure you’re on track.

Is it surprising?

If the reader can all but finish your sentences for you then no, it isn’t surprising, and no, it won’t be sticky. Taking an unexpected approach—particularly in situations where conventions rule—will give your writing more glue. One simple and highly recommended way to do this is to start your piece a couple of sentences into your argument. Write as you normally would, then try deleting the first one or two (or more) sentences. By removing the usual preamble you’ll create a jolt that will grab readers’ attention. Just throw them into the narrative and let them figure it out.

With a surprising headline like this we can’t help but be curious about the rest.

The highlights/non-crossed-out-bits spell out the “So what?” Two messages in one.

Not just what it is, but how to use it.

Would you want to hang out with this copy for South African accessories company Musica? Maybe—it’d certainly be a night to remember (assuming you survived).

Does it pass the “As opposed to what?” test?

A surprising number of organizations promote themselves using lines that don’t stand up to scrutiny. To avoid this, always ask yourself, “As opposed to what?” UK bank NatWest currently uses the tagline “Helpful banking”—as opposed to what, unhelpful banking? If what you say is obviously desirable then it won’t achieve cut-through—it’s just what any reasonable person would expect. Trying to make a virtue of a necessity can even sound a little desperate. Readers of a skeptical disposition (roughly 99 percent) might well respond, “Jeez, is that the best they can say about themselves?”

Does it pass the “So what?” test?

If your words are underwhelming then they’re unlikely to stick. The solution is to ask “So what?” This simple question is a brutally effective way of rooting out weak thinking. If the answer is a deafening silence or shrug of the shoulders then you’re off-target. Yes it’s cruel, but then so are audiences if they suspect their time is being wasted. What we’re suggesting is that everything you say has to have some reason to exist, usually connected to your audience and their wants and needs. Pointless puffery may fill the page but it drains audience interest faster than you can say “flannel.”

This subway ad for cancer charity breakthrough.org.uk borders on the brutal. Serious stuff.

Has it got real personality?

As so often in our line of work, it pays to compare what we write to people. The ones we’re attracted to tend to have the most appealing personalities. So one important question to ask is, “How personable is my work? If it were a person, would I be drawn to him/her or run a mile?” If your prose is the textual equivalent of a railfan with radioactive halitosis then clearly it needs more work. Your readers don’t have to fall in love with your on-page personality, they just have to avoid being actively repelled.

Classic pleasing-to-read copy from the Other Cola.

There’s an important concept that (bizarrely, in my opinion) hardly anyone ever talks about when it comes to writing for advertising: emotion.

We all know that human beings are primarily emotionally driven, and that rational stuffdoesn’t really motivate us at the most profound level. It’s just a thin veneer we pretend to have, to stop ourselves stealing other people’s cars and women.

Unfortunately, the rational stuffis usually what gets put in briefs— and in articles about how to write copy.

Nearly all the advice I see about writing headlines and taglines talks about how to make them impactful and memorable, using rhetorical devices like repetition (the US Army’s “Be all that you can be”), reversal (“Our food is fresh. Our customers are spoiled.”), rhyme (wartime slogan “Loose lips sink ships”), and alliteration (Brylcreem’s “A little dab’ll do ya”).

They never talk about freighting a line with an emotional payload, the thing that would make it truly powerful.

The FedEx tagline “When it absolutely, positively has to be there overnight” is undoubtedly a clever turn of phrase. But what makes it great is that it also captures the emotion of the package-sender— their desire for certainty. It’s this emotional content that elevates the best lines beyond being mere clever wordplay. After all, advertising is seduction...and without emotion, seduction won’t succeed.

After graduating from Oxford with a degree in philosophy and french, Simon had a brief and unsuccessful career as an investment banker. He then tried journalism, writing articles for women’s magazines about what men “really” like in bed. Finally he settled on advertising, and was a creative director at BBH in London and DDB in Sydney, before starting his own agency in 2012. His blog—Scamp—became the most popular ad blog in the UK and led to a book deal, with How to Make It as an Advertising Creative published in May 2010. Recently Simon has been crowdsourcing ads to promote atheism. As he puts it, “I may not be able to defeat God but I aim to worry him.”

Does it leave a striking image?

In many situations stickiness is an index of how rich you made your writing. Among other things, that means resisting clichés. No matter how strongly your client feels about a particular subject, we beg you to never, ever describe them as “passionate.” Even if it’s true, it’s a worn-out word that screams “WARNING: Hack at work.” And most of the time it’s a dirty lie.

Is it pleasing to read?

By “pleasing” we mean does it flow, is it well written in a formal sense, is its style appropriate, and perhaps above all, is it interesting? Notice we don’t say “entertaining”; that’s fine if the topic can support it, but most can’t. Instead we say “interesting” in its true sense—of interest to readers. And that comes back to the relevancy thing we talked about earlier. One thing’s for sure, if the copywriter was bored writing it, then the reader will be bored reading it. Perhaps the ideal situation is when you can’t help thinking or talking about the line you’ve just written, to the point of becoming a pest to your colleagues or partner. Sticky starts with you.

We’ve explained the background to making a message memorable, we’ve introduced some techniques to help increase your interest levels, and we’ve outlined some ways to check your progress while writing. Now it’s time for you to put all this into practice by writing us some sticky lines.

One piece of advice: don’t hold back—now’s the time to really let rip. Be bold and brilliant; even if you think you’ve gone too far, go further. In fact we suggest you always push your work as far as your imagination will allow; rest assured your client/boss will bring you back to earth if you’ve really overdone it.

Workout

PRODUCT AND CLIENT

You!

AUDIENCE

A prospective romantic partner.

TASK

Write one or more sticky lines that sell you to a prospective mate. This could be as obvious as a short dating-site ad, or as quirky as a tagline you append to your name. Or something else entirely.

BACKGROUND

Later in this book we make the point that pretty much everything —including individuals—can be considered a brand. This exercise is about putting Brand You into action. And hey, you might get a date out of it.