The Right Way to Write

Doing the basics brilliantly

This pre-Christmas copy gets straight to the point.

Here we explain the key principles of effective copywriting; in the next we introduce you to a series of techniques to make your work all but irresistible. Think of Lessons Two and Three as a crash course in the principles and practice of great copywriting.

Consider, if you will, the following response from E. B. White, author of Charlotte’s Web and Stuart Little, to a fan inquiring about his admirably stripped-down prose style:

There are very few thoughts or concepts that can’t be put into plain English, provided anyone truly wants to do it. But for everyone who strives for clarity and simplicity, there are three who for one reason or another prefer to draw the clouds across the sky.

As well as being a highly successful writer of children’s fiction, White was also co-author of The Elements of Style, one of the most important books on composition and form ever published.1 Written by William Strunk in 1918 and significantly revised by White in 1959, Strunk and White (as it’s usually called) has helped generations of authors improve their prose.

We mention this because (a) you could do a lot worse than acquire a copy of this pithy little book as bedtime reading and (b) White’s point that pretty much anything can be explained with clarity and simplicity is at the heart of this lesson. The process we describe in the following pages is ideal for any situation where you need to get your message across in strong, straightforward terms. We suggest you internalize it and make it your default approach—it’ll help you create effective base texts you can then build on to produce something more ambitious.

Remember, your work doesn’t have to be brilliant straight away—in fact it almost certainly won’t be. Getting a decent first draft down is a great confidence boost and the best—perhaps only—way to produce a second version with more magic. As Luke Sullivan, author of Hey Whipple, Squeeze This: The Classic Guide to Creating Great Ads and a contributor to this book, puts it, “First write it straight, then write it great.” Lesson Two is about straight, Lesson Three is about great.

One last point before we proceed. We’ve called this lesson “The right way to write” but of course there’s no “right way.” If our advice genuinely feels wrong then it probably is—at least for you. If it comes to a contest between your instincts and this book then go with your guts every time.

Amid all the brouhaha about carbon emissions, this straightforward message from Italian furniture-design company Lago feels like a breath of fresh air.

The humble napkin, transformed into a billboard for the brand’s environmental ambitions. They deserve a medal for “serviette-ish” alone.

Four steps to copy heaven

No one sits down at a computer or with a notebook and magically creates clear, compelling copy. It might look like that’s what they’re doing, but that’s only because they’ve internalized the approach we’re about to describe. No, going from nothing to something is a four-stage process during which you research, plan, write, and review.

Step 1—Research

Scrimp on research and you’ll be struggling to make up for it throughout the writing process. It’s not just about gathering facts and figures—essential though that is—it’s about finding a way into your raw material and establishing the “personal truth” of your subject (to borrow a phrase from Dan Wieden, founder of über ad agency Wieden+Kennedy).

Research starts with reading the brief. In fact don’t read it—interrogate it mercilessly until it reveals its secrets. They are the foundations on which the rest of your work should build.

The brief is of course the document that defines the project and your part in it. We say “document” but neatly typed letter-size sheets are the exception; more likely, your so-called brief will be buried in the body of an e-mail or form part of a hurried conversation in less than ideal conditions. The important thing to remember is this: Regardless of how your brief arrives, you need to dig deep until you’re 100 percent clear about

•The nature of the job

•The identity of the audience

•The problem you’re trying to solve

•The big idea you need to build on

•Any key messages your copy must contain

•The tone or personality of the finished piece

•When it needs to be done by

•Where to go for further information

Intelligent stuff from M&C Saatchi for Britain’s MI6 intelligence agency. Notice how the text messes with your mind, taking you down one train of thought before suddenly switching to another—like the job it advertises.

A brief template from BBH. A well-written and well-organized brief should contain all the information you need to get started.

There are 101 other things you might need to know, but these are the absolute essentials.

And what do you do if you don’t receive anything resembling a brief as described above? Why, you write your own. We don’t mean you make it up (at least you don’t admit to making it up); instead you unearth the information listed above for yourself. Never blame others for the scantiness of a brief (even if it’s their fault)—make it your business to uncover everything you need to succeed. If you don’t and the resulting work is off-target, no one will blame your briefer; they’ll blame you. Tiresome though it sounds, you really do need to know what you’re supposed to be doing before you start doing it.

One of the most important things the brief should tell you is who you’re writing for. We’ve dedicated a whole lesson to this later in the book, but for now we’ll just say you must know who your readers are in order to write effectively for them. “Must” is a strong word, but it’s the right one in this context. Your reader’s hopes, dreams, anxieties, prejudices, problems, and so on should form a sort of filter through which you sift the raw material you collect during this phase, enabling you to make it relevant. And none of that can happen if you don’t know who you’re supposed to be talking to.

This eccentric fact about chain stitching could only come from digging deep.

Finally, it’s impossible to write well about something you don’t understand, so the Research stage is about saturating yourself in the subject. Make notes. Draw diagrams. Talk to people—lots of people. Ask questions —lots of questions. Build up a library of information to power your prose once you start writing. Make your desk groan under the weight of your research. As long as you keep it relevant, there’s no such thing as too much background material.

Well, almost no such thing. If you’re particularly lucky/ zealous then you may face the problem of information overload, especially if time is tight and you’re not permitted the luxury of assimilation. The solution is knowing what you can safely ignore. That calls for confidence, and that comes from knowing exactly what you’re trying to do—which comes back to the brief. The better your understanding of your task, the better you’ll be able to judge what’s ignorable.

It would be hard—maybe even impossible—to write copy like this if you’d never spent a night under canvas.

Step 2—Plan

The Planning stage is where you clarify the problem your readers are facing and the solution your product/ service/brand is offering. In some cases this will be straightforward (“Embarrassing personal itching? You need our new super-strength antifungal cream!”). But in other situations the problem is less clear-cut. If you’re writing a marketing campaign for an art gallery there’s no “problem” as such. However, there might be a need, in this case, for a bit more culture in one’s life. So take a broad view of “problem” and “solution” but get to the bottom of them just the same.

Among other things, the Planning stage is where you get the thinking right.

Of course when your client/boss is screaming for it yesterday then the luxury of creative reflection is the first thing to go, along with lunch, going home at a reasonable hour, and other such nonessentials. Except that getting the thinking right is far from nonessential—in fact nothing is more important.

The best approach we’ve found is to have a conversation with yourself. Find a quietish place or go for a walk and just ask yourself what you’re really trying to do here. If you’re stuck use the classic who/ what/where/when/why/how list. Aim to get it down to a phrase or sentence. As always with planning, the more effort you put in here, the faster you’ll progress once you start the actual writing.

Once you’re truly clear about your challenge you can use this insight to whip the raw material you gathered during the Research phase into shape. Perhaps the easiest way to begin is by creating a “mind map,” with the key phrase or sentence that emerged during your internal conversation at its center. Getting your main themes down on paper like this will show where your train of thought is strongest and where it needs more work. It might also reveal connections between secondary ideas you hadn’t previously considered.

If you’ve several points to cover you’ll need to find some sort of connection or flow. In practice this means looking at your mind map and exploring different sequences of your main themes. Try a few alternative orders to see which works best, all the while remembering why your reader is reading your piece in the first place, and what they want out of it. Exactly how you structure your piece will depend on your audience, your subject, and your goal, although the following tried-and-true approaches should get you started.

Gyles and Roger’s mind map for Lesson Six of this very book. It ain’t pretty, but neither are they.

Ideal for short documents. You tee up the issues, explain their implications, and suggest some appropriate action.

Past>present>future

Explain how something came to be, what the current situation looks like, and where it could go next.

Context>analysis>conclusion>actions

This slightly more detailed structure works well for longer pieces. An alternative version that’s particularly useful for anything reportlike is Issue>background>current situation> conclusion>suggestions.

Problem>solution>results

The classic case-study format. Not particularly imaginative in its naked form but a solid basis on which to build.

Inverted triangle

The classic newspaper-story format. Start with a grabby headline, followed by the main points, before moving to detailed information and analysis.

Goal>step one>step two>step X>result

The classic instruction format. Start by describing what this process will achieve, then take your readers through the process step by step (beginning each step with a verb, because that’s the correct way to present any instruction). End by describing where they should be now.

Q&A

If you’re aware of the questions a reader might ask then cut to the chase and just answer them. Obviously this depends on knowing what your audience are actually after—there’s nothing quite as sad as Frequently Asked Questions that no one asks, frequently or otherwise. They make a brand look lazy and irrelevant.

If that’s not a product benefit we don’t know what is.

Ask any wordsmith about their criteria for writing and the chances are you’ll get a one-word answer: storytelling. They’ll often follow this up with how difficult it is to get the story just right. It can be a battle, and the way to win is through a combination of observation, imagination, and tenacity.

As a journalist and blogger I rely on observation before beginning the writing process. This is my favorite part because it feels as if I’m not doing very much even though I’m building the foundation of my entire piece.

Observation gets you in the “write” frame of mind—forgive the pun, but it’s true. I’ve covered New York Fashion Week for several years. If you think that means watching models walk by in various ensembles you’re absolutely correct. But it’s much more than that. Before I walk into the auditorium I’m already taking notes. What do people look like and what are they discussing? What’s the ambience? Is anything amiss? What’s the overall energy of the place? It’s much more than just jotting down clothing notes.

All these observations help the writing process, even if I never use the actual information I’ve collected. They help me answer my own questions and often catalyze a more in-depth or descriptive view of whatever it is I’m writing about.

Listening is also a key component. My work sometimes sees me interviewing actors, directors, and musicians, and listening is half the job. If you can’t give your subject your full attention, you’ll miss the good stuff. And if you aren’t prepared, you’ll have a difficult time focusing on your client or subject.

I once interviewed a somewhat shy musician, and I struggled to get them to open up and reveal something interesting about themselves and the album they were promoting. Then I remembered a book we’d both read. I mentioned this and the mood changed. We both relaxed and an interesting conversation began. When it came time to write my piece, I had so much more to work with.

You have to be willing to give more than you might get. You have to put in the work. And you need to give yourself a break and have fun with it when you get stuck. Writing is a self-reliant process.

Andi is a writer and performer living in Los Angeles. Her words have appeared in Vanity Fair, Monocle, Bloomberg Businessweek, and the Paris Review . She has written and performed for stages throughout the US, and her haiku poetry was featured on CBS Sunday Morning. In between taco tastings and cacti cultivation, she volunteers for the Young Storytellers Foundation and rants on her blog verbosecoma.com. She is currently at work on her first novel.

If we had to summarize Read Me in one sentence it would be this: Write like you speak, but speak well. This isn’t a particularly original idea—many people have said much the same thing over the years. The great adman David Ogilvy remarked, “I spend my life speaking well of products in advertisements.” Henry Ford advised his dealers to “solicit by personal visitation.” Clearly that’s not practical for most organizations, so copy that does the same job is the next best thing.2

As we suggested in the last lesson, effective copy tends to adopt the rhythms of speech. The tone of this exchange can be anywhere from thoroughly formal through to ridiculously relaxed, depending on the brand, the occasion, the medium and a host of other factors, but where possible we suggest you aim for a conversational feel. The great novelist Elmore Leonard summed this up nicely when he said,

“If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.”

But how exactly do you write in a way that doesn’t sound like writing? As we’ve already suggested, start by deciding what you’d say if you were speaking to your reader, then simply write it down.3 Another useful approach is to pay attention to pronouns. Use the first person (I, we, us, our) for warmth and to express subjective opinions. Use the third (s/he, it, they, its, their) for formality and to make objective points—the third person literally distances the writer and reader from the subject, positioning them as observers and not participants in the conversation. Use a combination of first person and second person (you, your) to create a direct relationship and establish a dialogue between writer and reader.

The power of “we.” It says, “Here’s a peek into our world; maybe you like what you see.”

The power of “you.” It’s strangely magnetic; we can’t help but look.

Not every organization will go along with the first-person familiarity we’ve just recommended, but if you’re speaking on behalf of a business it makes sense to use “we” instead of “the board” or whatever. Using personal pronouns enables you to build a closer connection between brand and reader with all the benefits that brings. Where possible, it pays to get personal.

Let’s move on. It’s important to understand that the writing stage is often a process of translation where you take raw research and convert it into polished prose that fulfills a particular purpose. You need to get good at this; the chances are, some variation of this translation process will form a large part of your professional life. Lord Rutherford, the father of nuclear physics, advised his underlings:

“If you can’t explain your physics to a barmaid, it is bad physics.”

Despite the implied slur on barmaids his Lordship was spot on—clear explanations come from clear thinking and real understanding. What we’re saying is, be aware of your place in the communications process—it’s you who sits between your subject and your audience, and it’s you who makes the former palatable to the latter.

How do you do this? Remember your readers. As we explain in Lesson Five, the simple way to do this is to ask yourself what you’d want to see if you were in their shoes. Let this simple insight steer your whole translation.

At the same time, it’s important to pay attention to the form of your words. When we speak we unconsciously vary the length of our sentences; when we write we should aim to do the same. The simple way to check this is to read your words aloud (or at least under your breath). Not only will this highlight any awkward phrases or dodgy syntax, it’ll also show where your flow ain’t flowing and your meaning ain’t meaningful. Reading back what you’ve written should become as natural as hitting the Save icon.

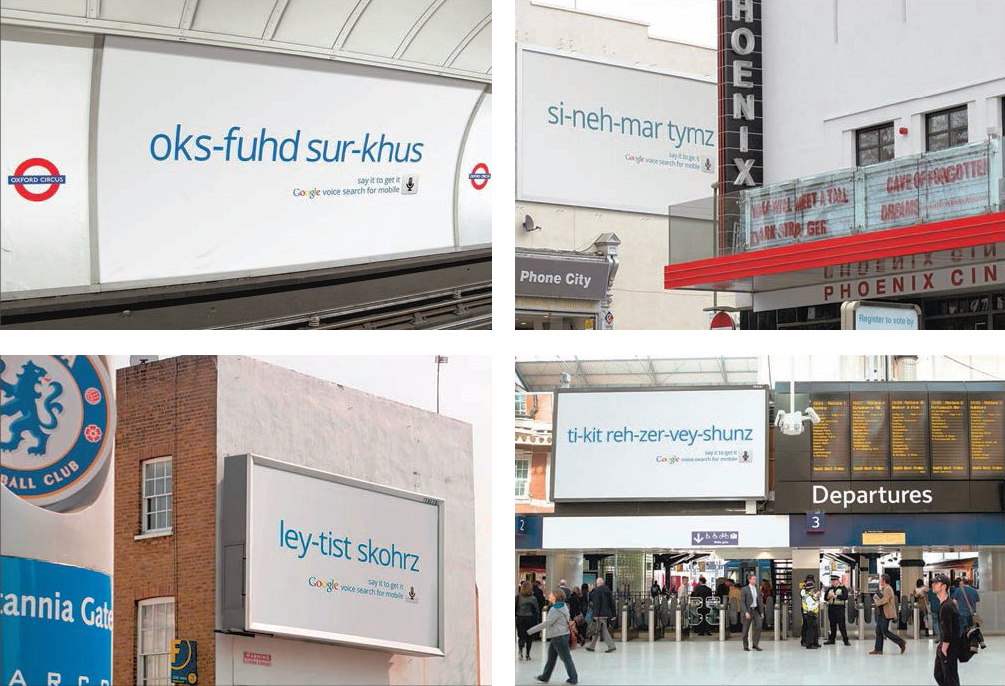

Google’s literal take on “write like you speak.”

It also pays to keep your paragraphs tight—in most situations five sentences are plenty. If a paragraph is running away with you then divide it in two. In fact, try to keep your whole piece as short as possible. We doubt anyone ever finished a piece of copy and wistfully sighed, “I just wish it were longer.”

Finally, a really useful technique for the Writing stage is to create a “core story.” This is just a fancy phrase for a document that contains everything important about your subject, written up under appropriate headings to a good (but not finished) standard. It’s a content pool that will itself never see the light of day—it’s almost certainly too long, for a start—but it can be a really useful resource during the Writing stage and is a great technique for ongoing projects that need multiple expressions of the same basic material.

Here’s how it works. Imagine you’ve been given the job of writing marketing material for a technology trade show. It’s an open-ended, ongoing job so you decide to put in a couple of late nights creating a detailed core story that will act as your copy repository. The result is perhaps three sides of paper, covering everything significant about said show. Imagine your satisfaction when the following day you’re asked to put together an HTML e-mail promoting the show’s launch—by lunchtime. Because you’ve already gathered everything you need in the form of your core story it’s incredibly easy for you to grab a sentence from here and a paragraph from there to quickly assemble 99 percent finished copy. A quick polish and you’re done.

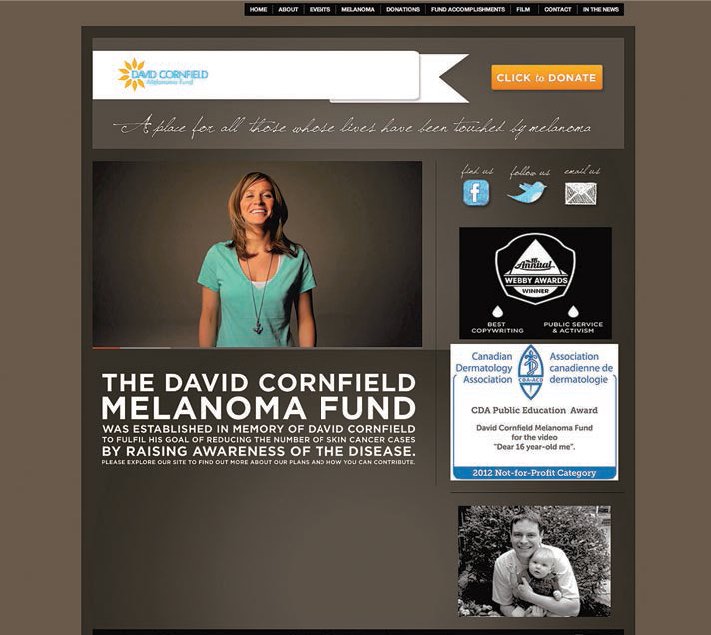

Taking a soft approach can deliver hard results. Here the friendly tone helps establish a rapport that makes a donation far more likely.

Then, two days later, you’re asked to put together a leaflet and some big banners to go in the show’s entrance hall; again you dip into your core story, pick the bits you need, and away you go. The following morning they’re screaming for a microsite, and again you dip and build in record time, earning the admiration of all who know you. So yes, creating a core story means a little extra work upfront, but it also means less work later as you’ll already have everything you need. In the right situation it’s a great technique and one we thoroughly recommend.

This is where you read over what you’ve done to make sure it does what it’s supposed to do. Reviewing is the polishing process during which you turn your sow’s ear of a first draft into the silk purse of your finished piece. That won’t happen in one pass—chances are you’ll need to go over your copy again and again, smoothing out imperfections and correcting shortcomings by degrees until you’re thoroughly sick of the wretched thing. Just remember: Every tiny tweak brings it closer to God.

It’s during the Review stage that you check you’ve done what the brief asked you to do. As your teachers no doubt told you at exam time, “Don’t write what you want to write, write what the question asks for.” It’s exactly the same with copywriting; don’t hand in some impressive but irrelevant wordplay; instead, make sure you know exactly what you’re trying to do— and when you’re finished, make sure you’ve done it. To do that we suggest you reread the brief. Even if you’re certain you’ve understood it, it’s worth checking your work against the brief one more time to make sure you haven’t inadvertently strayed into irrelevancy.

A series of people who’ve beaten skin cancer offer advice to their younger selves, ranging from the cheery (“Dear 16-year-old me, please don’t get that perm, it’s not as awesome as you think”) to the serious (“This is a cancer that shows on the outside. Start checking your skin now”). The result is funny, smart, moving, and generally wonderful. See the whole thing at www.dcmf.ca.

Perhaps our choicest piece of guidance for this stage is, “If in doubt, cut it out.” It isn’t always clear if a word, sentence, or paragraph should make the final version. If you can’t decide whether to hit the Delete key or not, here’s our advice—do it. If you’re asking yourself “Should I/shouldn’t I?” then you’ve already highlighted a problem and you need to fix it. It might seem harsh, but we suggest you don’t give borderline cases the benefit of the doubt. If that really troubles you then save multiple versions of your file in case you need to go back; the chances are you never will. As Mark Twain said,

“Eliminate every third word. It gives your writing a remarkable vigor.”

You also need to make sure what you’re saying is true. Your words could be supremely elegant yet complete fiction. Unless you’re making a virtue of hyperbole or your tone is obviously light-hearted (both perfectly good approaches, by the way) then whatever you write has to be scrupulously honest. Either stick to the facts, or depart from them with such chutzpah that no one in their right mind could mistake your piece for the truth.

Finally, if a good idea gets rejected by your client/boss then stash it away in your bottom drawer in the sure and certain knowledge that another opportunity to use it will come along sooner or later. Probably sooner. It’s amazing how often ideas created for one task can find a home in another—and because you’ve already done the difficult thinking part you’ll be able to produce them in record time, making you look super-efficient and eminently promotion-worthy.

If you can think clearly, and tell people what you’re thinking without boring them, you can probably write. Although this seems simple, two things tend to get in the way of good copywriting: bad craft and overused words.

In a sense grammarians are right; craft comes from learning the rules that govern a written language. But craft mostly comes from writing a lot. The best writers have a confidence and mastery born of endless hours at the keyboard. If you want to be a good writer you need to write everyday.

The more a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech is used in popular media, the easier it is to ignore. Don’t get into the habit of using overused words. Just parroting what you’ve heard before is lazy. This is a particular problem in marketing, a world that seems to make a virtue of using pretentious compound words when everyday English would be far better. Nothing masks meaning more effectively than jargon.

Writing well is not easy, but getting better is not complicated. Simply write a lot and write simply.

Nick is Global Chief Creative Officer at R/GA, one of the most respected digital ad agencies in the world. He began his career in design/corporate identity (including stints at FutureBrand in New York and Pentagram in London under the guidance of the legendary Alan Fletcher and John McConnell) before moving into advertising, and now works on both the traditional and interactive sides of the business. If anyone understands the broad sweep of creative communications in the twenty-first century it’s Nick.

It won’t have escaped your notice there’s plenty of poor writing out there—confused, over-complex, and under-stimulating. Of course you’d never create anything like that, and now’s your chance to prove it.

Workout One

Find a piece of copy that really makes your toes curl, then write a short analysis of why it’s so bad—a couple of paragraphs is enough. Justify your criticism as objectively as possible. The copy you choose can come from any source—packaging, ad, website, brochure, and so on. To keep things simple, pick something reasonably brief—say under 100 words.

Next, write one clear, strong sentence or phrase that describes what you think the original is trying to say. This should be the absolute essence of the message.

Finally, use the ideas and techniques covered in this lesson to write a new and improved version of the original, based on the essence you’ve just identified.

The aim here is threefold: Find rational reasons to back up your instincts (something you’ll be required to do in conversations and meetings on a regular basis), sensitize yourself to what a piece of text is really trying to say, and practice improving the work of others.

Workout Two

Plenty of real-world copywriting isn’t writing at all, it’s editing and reworking existing text. To get you comfortable in this role we want you to redraft the following chunk of copy—taken from a fictional airline print ad—in one of the structures we suggested earlier:

•Issues>implications>actions

•Past>present>future

•Context>analysis>conclusion>actions

•Issue>background>current situation>conclusion>suggestions

•Problem>solution>results

•Inverted triangle

•Goal>step one>step two>step X>result

•Q&A

Feel free to add and subtract details as you see fit. The aim is to build your confidence working with existing text, not scrupulously stick to the source material.

With great service, great food and great in-flight entertainment, we’ve made flying to the Far East more enjoyable than you thought possible.

There’s no reason why a long flight should be short on luxury. That’s why our seats are the comfiest in their class, with a massive 35in of space between rows so you’ll arrive at your destination relaxed and ready to enjoy your stay.

The soothing atmosphere isn’t just down to the seating— fabulous food and fine wines play their part, with menus designed by Andrew Walker, owner of Shanghai’s fabulous Starpool restaurant.

Then there’s our award-winning “100% Entertainment” system, featuring 10 movie channels, 12 TV channels (including Nickelodeon), 20 computer games, and 15 music stations with everything from classical to club hits. Your channel controller even doubles as the world’s first in-flight phone so you can let your friends know you’re having the time of your life.

However you look at it, flying with us is a truly elevating experience.

1. Elements has also come in for plenty of criticism, with detractors labelling it po-faced and appealing only to pedants. You decide.

2. The following quote provides a peek into Ogilvy’s world: “When you sit down to write your copy, pretend you are talking to the woman on your right at a dinner party. She has asked you, ‘I am thinking of buying a new car. Which would you recommend?’ Write as if you are answering that question.” Patronizing as can be, but Ogilvy’s advice is sound—write like you speak, just speak well.

3. In our writing workshops people often ask us for advice on how to express a particular point, usually beginning their query with the words, “I want to say….” To which we reply, “If that’s what you want to say then just go ahead and say it.” It’s great to see the lightbulb come on over their heads as they realize they already know the answer.