The Brand’s in Your Hands

What every copywriter needs to know about the B word

Rock paintings from “The Cave of the Hands” in Santa Cruz, Argentina. For the makers, their hand was literally their brand.

Without an appealing personality expressed in appropriate language, even the strongest brand will struggle to create an emotional connection with its audience. This matters because only one brand can be the cheapest; the rest have to find some other way of capturing their audience’s attention and earning their affection. Good writing is a great way of doing exactly that.

What do we mean by “brand”? It’s not as obvious as it sounds. Apple undoubtedly qualifies, as do the likes of Mercedes, L’Oréal, and Gap. But what about Lady Gaga? Or Damien Hirst? What about Belgium, Greenpeace, al-Qaida, or Harvard? Are you a brand? Why? Or alternatively, why not?

We need to get to the bottom of brands because as copywriters the chances are we’ll spend most of our careers working with them. On the surface we’re here to sell ideas, products, or services, but our deeper mission is almost certainly to build brands. As we pointed out earlier, in many ways it makes sense to call what we do “brandwriting” rather than “copywriting.”

And that’s where the problems start, for “brand” defies easy definition. We’ve all got an intuitive idea of what it means, but putting that into words can be surprisingly tricky. So without further ado, let’s look at three definitions that illuminate different aspects of this elusive issue.

Definition one—names and logos

Here’s a valiant attempt to define “brand,” courtesy of the American Marketing Association:

A name, term, design, symbol, or any other feature that identifies one seller’s goods or service as distinct from those of other sellers.

So for the AMA a brand is a means of differentiation. That’s certainly true, but it’s a somewhat limited interpretation. It works well enough for consumer items like cereals or soap powder, but where does it leave the likes of plucky Belgium? High and dry, that’s where. No, in many cases the brand = logo equation lacks real explaining power.

Definition two—what you do and how you do it

Interbrand—the global branding business and Gyles’s erstwhile employer—define “brand” thus:

A mixture of attributes, tangible and intangible, symbolized in a trademark, which, if managed properly, creates value and influence.

That’s a big step in the right direction. The implication is that a brand is more than a logo, it’s also an attitude, a way of doing things, an aura that surrounds a person, place, or thing. Interbrand’s definition suggests that, with the right presentation and management, more or less anything can become a brand.

So the answer to the various questions posed in the opening paragraph of this lesson is a great big “yes”— all those entities either are or have the potential to be brands. Lady Gaga doesn’t have a logo as such (certainly not in the same way as Coca-Cola, with its rigorously policed corporate identity), but no one would deny she’s a mega-brand. Put it like that and it’s clear that “brand” is a flexible concept, able to embrace almost anything.

You could argue that if everything is a brand then nothing is, in the sense that as soon as the advantage offered by brand status is available to all then it’s no longer an advantage—instead it’s just the new normal. It’s possible this infinite elasticity will prove to be the brand’s undoing, and in the future we’ll have to invent some new way of thinking about the world. But that’s another book.

Definition three—promises and expectations

Hang around with brands for long enough and you’re sure to hear the phrase, “A brand is a promise.” Here’s what it means. Buyers tend to have certain expectations of their purchases, thanks to the endless marketing messages they’re obliged to digest. BMW? Why, it’s the Ultimate Driving Machine. Budweiser? We think you’ll find it’s the King of Beers. These slogans are claims, but they’re also promises. They’re saying, “Buy me and look what you’ll get!, The ULTIMATE Driving Machine!, The KING of Beers!, We promise it!” So not unnaturally, people expect their purchases to deliver.

What happens next is that the brand’s claim gets tested in real life, which turns the promise into experience, either good or bad. What’s more, that experience sets future expectations, so if Driver A agrees that his latest BMW really is the Ultimate Driving Machine, it’s now incumbent on BMW to make sure the next model he buys is just as good, if not better. If, three years down the line, Driver A decides his replacement Beemer is merely a Moderately Good Driving Machine then the promise has been broken.

There’s a tendency in modern marketing to describe everything in terms of experience, in much the same way as there’s a tendency to describe everything as a brand. It ain’t necessarily so. When a hungry shopper visits a supermarket they want sausages for their supper, not an extruded pork experience. To misuse language in this way weakens and debases “experience,” turning a useful concept into a useless cliché. Listen carefully and you can hear Orwell tutting from beyond the grave.

The crucial thing to remember is that, strange as it may sound, the brand owner doesn’t own the brand. They own it in a legal sense of course, but the thing that makes the brand powerful—its reputation, its aura, its promise—is 100 percent in the hands of its audience. It’s the difference between how we describe ourselves and how others describe us. As Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon, has remarked:

“Your brand is what people say about you when you’re not in the room.” 1

We could add any number of extra definitions, for example a brand is a channel, a brand is a conversation, a brand is a relationship…. This profusion of descriptions only underscores our earlier point that “brand” can mean virtually anything. The ideas we’ve presented here—that brands are more than their logos, they’re largely about intangible appeal, and they’re ultimately owned by their audiences—are an excellent foundation.

Apple’s “I’m a Mac and I’m a PC” is pure “personality as difference.” They’re exaggerating for effect but there’s more than a grain of truth in there.

Clearly all sorts of things can prevent a brand from delivering on its promise, leading to nasty things being said behind its back. Almost all of them are outside the copywriter’s control—it might be poorly designed, badly made, too expensive, last season’s color, and so on. We’re not entirely powerless, however, and our biggest contribution comes from writing about the brand in a way that encourages attraction.

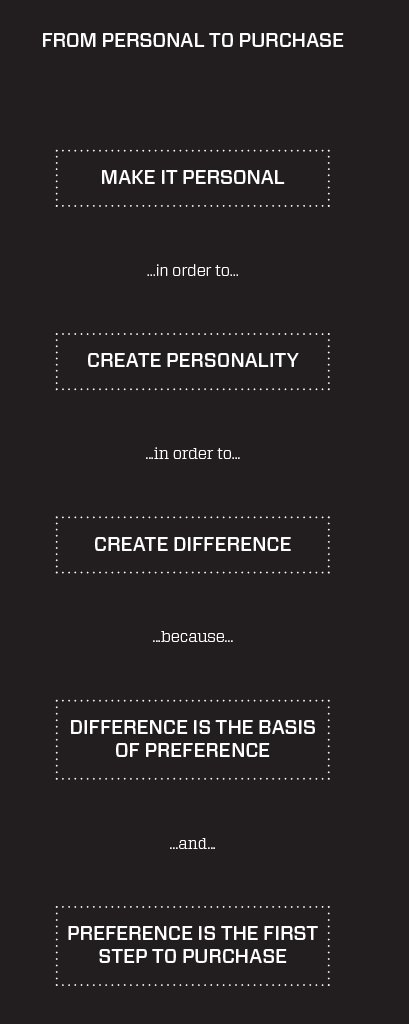

So how do we do this? How do we turn an ordinary brand into a love brand, one for which audiences feel real affection? The answer is we make a personal connection with our readers, because that gives us the opportunity to create an appealing personality, which in turn enables us to create significant difference.

Make a personal connection

It’s often said that “people buy people”—in other words, what closes a sale is the man or woman making the pitch, not the mute product or service being pitched. OK, if whatever you’re selling happens to enjoy some overwhelming technical or price advantage then the logic changes, but in many cases a sale is the result of some sort of human-to-human interaction—in other words, a personal connection. And that means introducing some emotion.

The emotional trumps the rational because it allows people to identify—whenever someone describes themselves as “an Apple obsessive” or “a Nike addict” that’s exactly what’s going on. These emotional connections are about how we see ourselves and the tribe we belong to (or aspire to belong to). Our job as writers is to support this process, using language in a way that encourages readers to join the club by aligning themselves with whatever brand we’re promoting. We’re not suggesting you discount the rational—if you’ve got solid reasons for the reader to buy/believe/whatever then work your facts hard. Instead we’re saying take an enlightened approach that acknowledges the importance of emotions and uses all the material at your disposal to its maximum effect.

Create an appealing personality

This emotional dimension often comes from the tone we use—in other words, the personality we create in our writing. What we’re talking about here is verbal identity2, the way a brand conjures up a clear and meaningful personality for itself using words alone. This process is driven by values, the principles3 and beliefs a brand claims to hold dear. It’s just common sense—if someone or something behaves in a way that somehow matches our personal beliefs then there’s a decent chance of a bond developing.

So while not exactly simple, the copywriter’s challenge is straightforward: we need to make the brands we write about likeable by imbuing them with characteristics that are both appropriate (in the sense that they genuinely reflect the brand’s values) and appealing (in the sense that they attract the right audience, and keep them close once they’ve been drawn in).

Use personality to create difference

So far we’ve established that an emotional connection is the basis of much effective copywriting, and that a brand’s verbal identity helps create and sustain that connection. This process becomes even more significant when we consider that brands are in competition with each other, yet the products or services they represent are often strikingly similar (if you’re lucky enough to be writing about something with a genuine point of difference then happy days).

In this situation the personality you create for a brand can make a decisive contribution to its success. What you’re really doing is creating difference, and not just any difference—this is appealing difference that makes a difference.

The good news is we’re pre-programmed to find difference, as Jeremy Bullmore has noted:

The human mind both abhors and rejects the concept of parity. Give a small boy two identical marbles and within an hour he will have formed a preference for one.

So our job is to help our readers form the right preference by giving our brand an attractive personality and bringing that personality to life in a way that appeals to people. The result will stand out in a sea of sameness.

Like any successful brand, British Airways uses its advertising to project a distinct personality that helps it stand out in a crowded market. Compare its comms to those from other airlines and you’ll see what we mean.

I think back to when I was just starting out in this industry: a fresh, young creative assistant happily (or fake-happily) running out to get coffee twice a day and picking up dry cleaning on the way back, dreaming of future advertising glory.

And I have words for that girl.

Silly twit, I would say as I not-so-gently shake her shoulders. When acquaintances ask you how you’ve been, try not to vomit up a monologue on the complexities of your latest retail ad.

When your parents ask you what exactly it is you do for a living, don’t rant to them about awards shaped like writing instruments or wild animals.

Also, saying you’re watching something just to see the commercials is like saying you only read Playboy for the articles…but really meaning it.

If you think only about advertising, talk only about advertising, study only advertising, and hang out only with advertising people, you will be a huge bore.

Do not be a bore.

It’s not good for you. It’s not good for the people that have to sit next to you at dinner parties. And it’s definitely not good for your creativity—which means it’s not even good for your career.

Take a foreign language class for no reason. Go on a solo trip to an exotic country. Wander around and get lost in your own city. Enrol in a cooking class on donut making. Fail that cooking class.

Just do not be a bore.

And, by the way, no matter how high and mighty you may eventually think you are, remember you used to be that assistant with the dopey grin and coffee stains down the front of her shirt.

Kim has done hard time at an impressive range of top US ad agencies, including Droga5, BBDO, and TBWAChiatDay. Along the way she’s garnered an equally impressive range of awards and curiously shaped mantelpiece adornments. Today she’s a brilliantly capable creative director based in New York with—to quote one of her colleagues—“solid digital chops.” We’re not 100 percent sure what that means but it sounds mighty impressive.

Making it happen

Putting this into practice means returning to an idea first mentioned in our lesson on audiences—“Whose voice should we hear when we read the words?” We said this is a key question—perhaps the key question —to ask when searching for the right voice for a particular readership. It’s equally relevant here.

To understand why, we need to acknowledge that reading begins with listening. As our eyes track along a line of text the squiggles of ink they encounter aren’t magically transformed into thoughts, memories, and so on. Instead they have to go through an intermediate stage where they take the form of inner dialogue (or “silent speech,” as cognitive psychologists call it). Children often move their lips in time with this silent speech; adults—even art directors usually don’t.

So reading is really the act of listening to this silent speech as it plays out in our head.

Our point is that this silent speech can have just as much personality as normal speech. If the copywriter is sufficiently skillful then the inner dialogue their words create will have all the traits of the most evocative vocal speech. In fact they’re essentially the same thing, it’s just that one is internal and the other external.

Achieving all this is agreeably easy. To exploit inner dialogue’s ability to create personality, simply picture a real-life individual with the same traits as the brand you’re dealing with, then write with their voice in mind. Essentially this individual becomes your voice model.

It’s like an actor getting into character as preparation for a performance. And just like an actor, the most effective way for a copywriter to understand the voice of their character is through research. If your model is a public figure, then find some online videos of them in action and create a list of their verbal mannerisms. How do they speak? What unusual turns of phrase do they use? How do they start a sentence? Or end one? How do they express pleasure? Or dissatisfaction? What do they always say? What would they never say? And so on. Make a list, the more detailed the better.

It’s exactly the same if the individual you’re modeling isn’t in the public realm, although obviously you can’t rely on YouTube. In this situation you could use a number of public figures as references sources and build up a sort of composite description of the voice you’re after, taking different mannerisms from different individuals. Either way, you need to reach a point where you’ve a clear idea of how your brand would speak if it were this person. It’s then a reasonably straightforward job to give your copy instant personality by merging these verbal mannerisms with your raw material.

Recently Roger used this approach to good effect while writing for a charity that looks after some of London’s most historic landmarks. The client had identified a popular TV historian as the voice of the brand, so Roger was able to quickly build up a list of the historian’s verbal tics and use them to enliven the client’s source text. The result had plenty of personality and took hours rather than days to create. Try this technique yourself—it works.

How a brand’s various components work together.

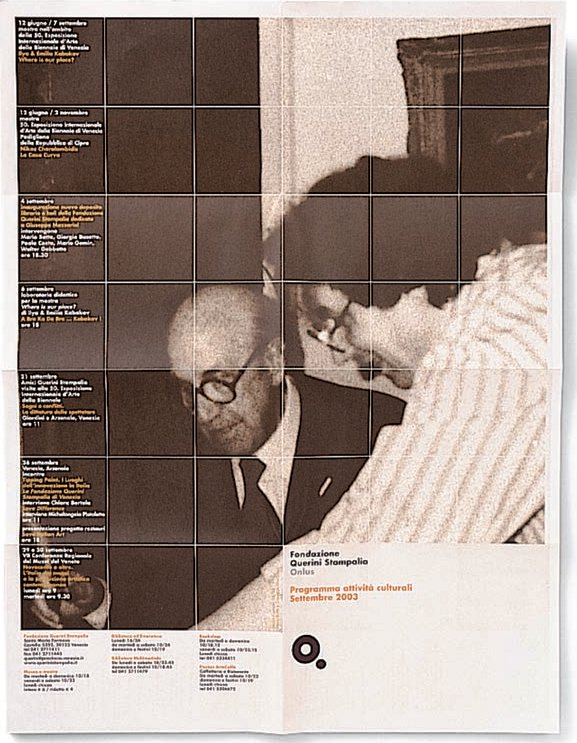

This clean, uncluttered identity for Venetian cultural institution Fondazione Querini Stampalia shows how a small number of brand elements can be used in all manner of ways across all manner of media.

Halifax makes a feature of their staff in their ads. It’s a tried-and-true approach, and part of their brand.

Brand basics

Before we end let’s take a quick spin through the nuts and bolts of brands. Digest what follows and you’ll be able to talk branding with the best of them.

Brand components

A big idea or essence is the central thought that captures a brand’s main point of difference. It’s often a single word or short phrase. In his book, The Big Idea, UK brand expert Robert Jones writes that Apple’s essence is “different” while management consultants McKinsey & Company’s is “rigor.”

A brand’s values refer to the principles it lives by, usually expressed as a series of adjectives. At the time of writing, HSBC’s values are “open,” “connected,” and “dependable.” Values are, in effect, a set of benchmarks that brands use to define their behavior, although how many genuinely allow their values to steer their corporate conduct is hard to say. In many cases it might make more sense to talk about “aspirations” rather than values; however, let’s not get sidetracked.

Next, a brand’s vision describes its ambition for the future. Early in its life Nike’s vision was reportedly to “Crush Adidas,” while Heinz were guided by the considerably less macho, “To be the world’s premier food company, offering nutritious, superior-tasting foods to people everywhere.”

Finally, a brand’s personality refers to the human character traits a brand adopts to make itself likeable and relevant. Nokia define their brand personality (and, by extension, their tone of voice) as “authentic,” “sociable,” “curious,” and “enthusiastic.”

Iconic design is the basis of these brands.

Brand expression

Design

This refers to logos, color palettes, typefaces, photography, and illustrations, and the rules governing their use. These elements come together to form what’s sometimes called an “identity system”—the totality of visual elements that represent a particular brand. Most identity systems are rigid (in the sense that there’s a single logo and so on, with very definite rules governing its use); others—for example Tate Galleries in London, the MIT Media Lab in Massachusetts, or the City of Melbourne in Australia— have scope for variation in their design and art direction.

Names

Brand names come in a number of fruity flavors. They can be descriptive (Toys R Us), evocative (Amazon), or superlative (Mr Muscle). They can borrow from a place connected with the product or service in question (Wall Street Journal, Singapore Airlines), they can use the founder’s surname (Ferrari), first name (Ben & Jerry’s), or a group name (Quaker Oats). They can be an abbreviation (Intel, FedEx), an acronym (BBC, KFC), or a neologism (Prozac, Xerox, Kodak). The main thing to know is that brand naming can be a tricky business and despite what some agencies might say, intuition counts as much as method when it comes to picking a winner.

Figurehead or public face

These come in two broad types: those with a genuine connection to the brand (the late Steve Jobs for Apple, Sir Richard Branson for Virgin), and those who’re paid to stand in front of a camera (any actor or celebrity fronting any campaign). The former isn’t necessarily more effective than the latter—it’s fair to say Bill Gates was never a particularly persuasive advocate for Microsoft, despite the fact it was basically his idea.

Staff behavior

These are the folks who actually deliver the product or service that the brand represents. As most of us know from personal experience, a surly or stupid member of staff can ruin our view of an organization faster than just about anything. If they get it wrong then all the hard work and expense that goes into building a brilliant brand can be undone in seconds. Staff behavior is an incredibly important and often underappreciated part of how we experience brands.

Products and services

These are the things the brand actually represents, and clearly they have to deliver. It’s sometimes said that good advertising helps a bad product fail faster. That’s because it draws attention to its shortcomings and emphasizes the yawning void between a brand’s promise and the actual experience it delivers.

Language

Our bit. Brand language covers everything from the brand’s name and tagline/slogan, through to ads, annual reports, articles, brochures, case studies, data sheets, direct-mail pieces, flyers, leaflets, letters, newsletters, packaging, posters, presentations, scripts, signage, speeches, social media, websites, and plenty more besides. As this list suggests, words are a fundamental part of virtually all brands, which is of course what this lesson is about.

And finally…

Brands are also expressed in product design (think the classic Coca-Cola bottle or the original VW Beetle), trade dress (think UPS’s brown trucks and uniforms), and sound (think Intel’s four-note “flourish” or “Mmm, Danone”). On this last point we could legitimately say a country’s national anthem is its sound signature (in the same way that its flag is its logo), and that a TV show’s theme tune is a major part of its brand.

When you’re writing for the Web: Read your work out loud.

When you’re writing for radio: Read your work out loud.

When you’re writing for film, TV, or animation: Read your work out loud.

When you’re writing a press ad, a letter, an e-mail, a blog post, a presentation, a brochure, a press release, a proposal of marriage, or the copy for a can of beans: Read your work out loud.

It will help.

Creative Director of Punch It Up, Mandy is a writer who also runs workshops to punch up the creative output of organizations ranging from banks to the BBC, and artists to ad agencies. Before Punch It Up she ran Mandy Wheeler Sound Productions, an award-winning production company with whom she turned out a couple of thousand ads and numerous radio programs.

Not surprisingly the best brandwriting happens when a brand has a distinct personality for the writer to spark off. The better you understand a brand’s personality (and the voice that articulates that personality), the better your writing will be.

Workout One

We’ve said “Whose voice should we hear?” is an important question to ask when writing for brands. To emphasize this we’d like you to rework the following copy…

Domaine du Colombier

This gorgeous golden wine is fresh, fruity, and incredibly drinkable. Made from 100 percent Chardonnay grapes and bursting with the flavor of kiwifruit, limes, and apples, it’s a classic Chablis from the rolling chalk hills of northern Burgundy. All our winemaster’s years of experience have gone into selecting a wine with the ideal balance of dry finish and honeyed taste. It’s part of our commitment to bring you the finest wines at the lowest prices.

…in the voice of one of the following figures:

Robert De Niro

Homer Simpson

Borat

Queen Elizabeth II

Gordon Ramsay

Fred Flintstone

There’s a lot of information in the original, and you don’t have to get it all in. Instead concentrate on making sure your chosen voice comes though loud and clear. Here’s the clincher: Show (don’t read) your work to a friend and ask them to identify the “speaker”—if they get it right without any prompting then you’ve succeeded.

Workout Two

If not, you need to turn up the volume on your chosen voice.

Let’s explore the idea that personality, expressed through language, is the basis of a brand’s audience appeal.

First find a brand with strong, clear personality (you’ll probably want a B2C brand as these tend to play up their personality compared to their B2B brethren).

Next describe that brand’s verbal identity—a few well-chosen adjectives should do it. Now ask yourself to what extent is that identity appropriate given the brand’s particular line of business? In other words, have they chosen wisely? Is their identity an asset or an irrelevance?

Next, to what extent is the brand’s verbal identity appealing? Does it help attract the right audience? Could they do anything differently to increase their appeal?

Finally, how does this verbal identity create difference, enabling the brand to stand out from its competitors?

1. Another fine Bezos brand quote is, “A brand for a company is like a reputation for a person. You earn reputation by trying to do hard things well.” Similar point, different language.

2. Verbal identity is essentially the same as tone of voice. For us the difference—such as it is—centers on application. Verbal identity is an expression or description of a brand’s on-page personality, whereas tone of voice is about the actual words a brand uses in ads and so on.

3. One of advertising’s greatest figures—Bill Bernbach—once pronounced, “A principle isn’t a principle until it costs you money.” It’s a great line and a nice idea, but how many businesses actually follow their principles/values in this way?