A Catalogue of Swindles and Perversions

What George Orwell can teach copywriters today

The man himself.

Lessons Two and Three work together to help you improve the art and craft of your writing. This lesson adds color to what you’ve just read, with priceless rules to rev up your writing from one of the true greats of twentieth-century literature.

In 1946 George Orwell—ex-private schoolboy, Spanish Civil War veteran, and one-time vagrant —published his now-famous essay, Politics and the English Language. Although a critique of the blather and balderdash employed by professional politicians in the 1930s and ’40s, Orwell’s observations are remarkably perceptive and have much to say to copywriters today.

In this lesson we’ll take you through Orwell’s essay, commenting on it and pointing out its relevance as we go. We strongly advise you to read the original—it’s freely available on the Web, it’s written in an easy, accessible style, and it’s certainly worth an hour of your time. Orwell once commented that “good prose should be like a windowpane, in the sense that its meaning should be perfectly clear—a quality Politics and the English Language has in abundance. Give it a go.

“Good prose should be like a windowpane.”

Why are we bothering you with the thoughts of a long-dead novelist? For the simple reason that Orwell was a supremely talented prose stylist. We don’t mean he was a posturing virtuoso, running up and down the scales like Mozart on amphetamine, but rather that he had a profound understanding of how to make language work. The New York Times Book Review recently included a letter suggesting, “If you want to achieve true mastery of English prose, read Gibbon and Orwell, then shoot yourself.” That may be going a little too far, but Orwell undoubtedly had a gift for getting his ideas down on paper with an inspiring blend of clarity, brevity, and impact—which is good copywriting in a nutshell. That’s why Orwell matters, and that’s what this lesson is about.

The essay itself.

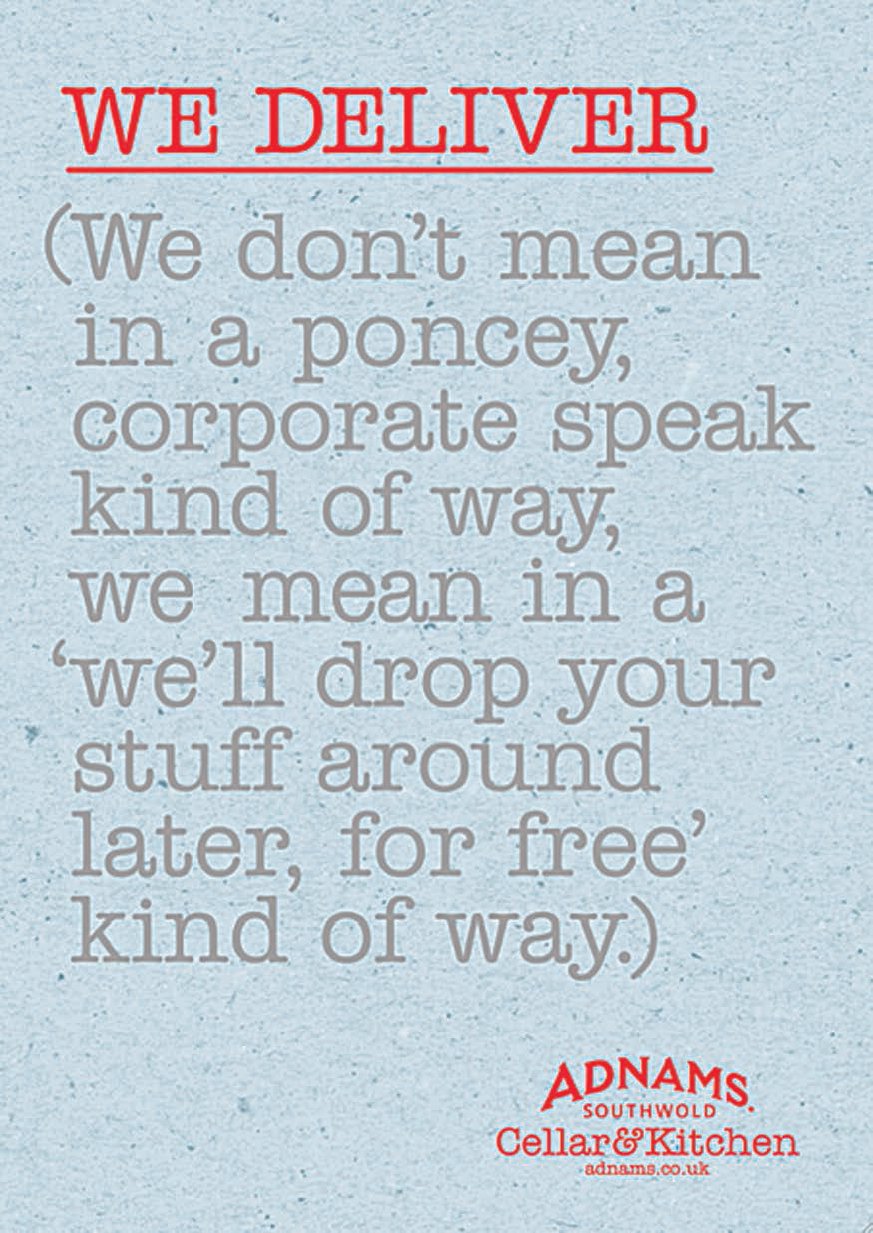

Personable copy that celebrates everyday language and takes a stand against the windy waffle Orwell hated.

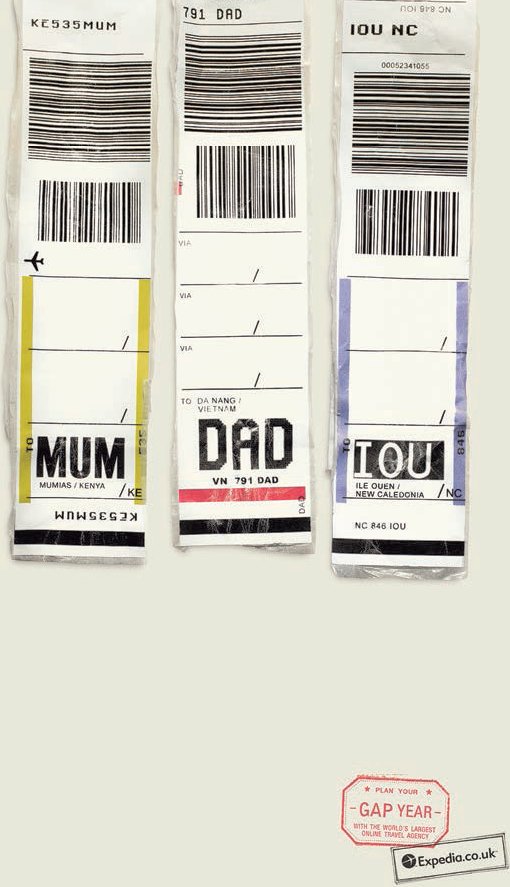

Copy rooted in reality. According to legend, “Just do it” took just 20 minutes to write, yet still works brilliantly well 30+ years later.

Politics and the English Language

Let’s begin, appropriately enough, at the beginning. Orwell starts his essay thus:

Most people who bother with the matter at all would admit that the English language is in a bad way, but it is generally assumed that we cannot by conscious action do anything about it.

As a copywriter with a keen interest in language, Orwell’s phrase “most people” includes you. Is it an exaggeration to say our language is in trouble? What do you think? Orwell’s own view is pessimistic (not without reason, as the examples we’ll come to in a moment make clear) but ultimately positive, in that he offers a range of practical techniques we can use to change things.

The second part of the sentence highlights the common belief that language is a given and something that can’t be altered. In fact, as Orwell goes on to show, it’s easily changed, and indeed it’s up to all of us to alter it whenever we think it necessary. We think that’s a pretty important mission.

Next Orwell offers “five specimens of the English language as it is now habitually written” that “illustrate various of the mental vices from which we now suffer” —or to put it another way, a bunch of examples that show what’s wrong with contemporary writing. To give you a flavor, here’s the first:

I am not, indeed, sure whether it is not true to say that the Milton who once seemed not unlike a seventeenth-century Shelley had not become, out of an experience ever more bitter in each year, more alien to the founder of that Jesuit sect which nothing could induce him to tolerate.

Professor Harold Laski (Essay in Freedom of Expression)

Lordy. Orwell’s complaint about lack of precision seems entirely justified. Remarkably, this sort of convoluted writing is still common, as a quick trip to plainlanguage.gov, or plainenglish.co.uk (for UK examples), will confirm. Here’s an example taken from a project Roger worked on recently. To stop your brain melting we’ve included a translation:

Before

Effectual winter upkeep of transport infrastructure poses sizable logistical challenges for all those responsible for maintaining the smooth running of road systems.

After

During winter it can be hard to keep roads open.

What’s remarkable is that the “before” version displays the same shortcomings and “mental vices” Orwell railed against over 60 years ago. As he put it:

The writer either has a meaning and cannot express it, or he inadvertently says something else, or he is almost indifferent as to whether his words mean anything or not.

Before adding:

This mixture of vagueness and sheer incompetence is the most marked characteristic of modern English prose.

Unfortunately there’s some truth in this. As the above examples show, it’s not hard to find professionally written text that appears determined to avoid saying anything. Orwell goes on:

As soon as certain topics are raised, the concrete melts into the abstract and no one seems able to think of turns of speech that are not hackneyed.

We call this tone of voice “default bureaucratic”—it’s what inexperienced writers reach for when they lack the confidence to express themselves in any other way (we don’t say this as a criticism, simply as a fact). “Default bureaucratic” is characterized by rambling sentences, unfocused paragraphs, passive verbs, poor word choice, and—above all—no real understanding of the reader and why they’re reading the piece in the first place. Note, “default bureaucratic”; we’ll return to this textual turd several times before we’re done.

The best advice I ever read about writing is this: The writer’s only responsibility is to get the reader to turn the page.

That’s truly brilliant because it’s very easy to lose sight of the point of a piece of writing. Often a writer will try to persuade the reader of his or her genius, or cram in every possible piece of information, or worry that they’re not good enough.

But none of that matters.

Whether you’re P. G. Wodehouse, Jeffrey Archer, or a copywriter working on a 20x4 press ad for cut-price asparagus, if you’re not getting the reader to read on then you aren’t doing your job.

That task can be accomplished in many ways. Mr. Wodehouse would write such wonderful sentences and such hilarious jokes that the reader would want to extend their experience. Mr. Archer, like him or not, uses plotting, structure, and themes to keep millions of people turning the page. And the copywriter can’t just stop at the asparagus’s price; he must express it in a way that makes the reader want to find out where the offer is available and care enough to do something about it.

The really great thing about this rule is that it removes the spurious concept of quality from the process. After all, what is quality? There are a million subjective answers. For some it is about originality; for others it concerns elegance of phrase; for still others it lies in immaculate, labyrinthine plotting, but none of those things can be objectively evaluated. You can and should only do what you think is good. In fact do whatever the hell you like—just get your reader to turn the page.

At school, English was the only subject Ben was good at, but he didn’t fancy doing a huge amount of work, so when he left he found a job as a copywriter at AMV BBDO in London. To his great shock he soon discovered that a great deal of work was required. From AMV he became Creative Director of Lunar BBDO, but in his spare time he wrote a novel (Instinct) that was published by Penguin in December 2010. Ben is now Creative Director of Media Arts Lab, working exclusively on Apple’s advertising across Europe, but in his spare time he continues to write novels and screenplays.

Back to Politics and the English Language . Orwell complains that:

Prose consists less and less of words chosen for the sake of their meaning, and more and more of phrases tacked together like the sections of a prefabricated henhouse.

This is a recurring nightmare for Orwell—clear, original writing supplanted by the splicing together of clichés. The result isn’t writing, it’s assembling—a patchwork of existing phrases cobbled together to fill a space.

Next Orwell describes four “tricks by means of which the work of prose construction is habitually dogged” —dying metaphors, verbal false limbs, pretentious diction, and meaningless words. Let’s delve a little deeper into these excrescences, which Orwell delightfully describes as a “catalogue of swindles and perversions”.

Dying metaphors

Here Orwell is complaining about worn-out metaphors and over-familiar imagery. He’s comfortable with dead metaphors (word pictures that have lost their power through overuse) and live metaphors (vivid verbal images that can really help comprehension). It’s dying metaphors—phrases that have become clichés through overuse—that drive him nuts. Orwell lists some of the worst offenders as he sees it: ring the changes, toe the line, ride roughshod over, stand shoulder to shoulder with, and play into the hands of . We could add whole new ball game, at the end of the day, low-hanging fruit, or, our personal bête noir, any use of passionate (in a business context).

No pretentious diction or meaningless words here.

Refreshingly direct copy. Well, it’s the thought that counts.

This section focuses on the tendency of writers to use complex verb phrases rather than straightforward, freestanding verbs. That’s not as technical as it sounds; all it means is that Orwell prefers “leads” to “play a leading role in,” “serves” to “serves a purpose,” and so on. Nothing to disagree with there.

He’s also highly critical of passive verbs (or the passive voice, as it’s sometimes called), a consistent feature of poor prose. Like Orwell we’re not grammar sticklers, but active and passive verbs are something all copywriters really do need to understand. Don’t panic, they’re surprisingly straightforward, as we’re about to explain.

Verbs come in two basic forms—active and passive. In the active form it’s immediately clear who’s performing the action mentioned in the sentence. Take the phrase “I heard it through the grapevine”—the very first word makes it clear who’s doing the hearing. In the passive version—“The grapevine was where I heard it”—we don’t find out who’s doing what until far later. While that’s not the end of the world, passive verbs soon make a piece of writing feel flabby and vague.

There’s one situation in which the passive form is perfect—when you want to avoid giving offense or attributing blame. If you’re writing about a sensitive subject and you’d prefer to save someone’s blushes, say something like, “This year’s sales targets weren’t met,” instead of “Our sales team didn’t meet their targets this year.” Your author Roger remembers an incident at school when he accidently broke a fretsaw blade during a woodwork lesson. Roger approached his teacher with the words, “Sir, the blade got broken.” Without looking up, the formidable old schoolmaster replied, “You mean, ‘I broke it,’ boy.” Despite his questionable belief in the educational power of a sound thrashing, Mr. Howe’s attitude to active vs. passive verbs was spot on.

Or to put it more directly, using showy words to seem big and clever. The author’s aim, as Orwell puts it, is to “dress up a simple statement and give an air of scientific impartiality to biased judgements” or else “give an air of culture and elegance” where one is lacking. Neither is good.

Meaningless words

Many institutions seem curiously compelled to write utter drivel. What’s worse, we accept it and actually expect no better. Usefully Orwell suggests a practical way for us to judge the clarity of a piece of writing— count the syllables. The more syllables, the further away a word is likely to be from the clarity and power of everyday speech. Sadly Microsoft Word’s word count feature doesn’t do syllables so you’ll have to tot them up manually.

Orwell’s point is that a writer’s syllable count rises in direct proportion to his or her use of nonsensical, overblown language. He suggests the wordy version is the one most people would produce when asked to write something “official” sounding. Well, yes and no. Many writers do indeed pile on the syllables in formal situations. But in our experience even novice writers are perfectly capable of using what we might call a “default human” approach (rather than the “default bureaucratic” we talked about earlier)—they just need a little encouragement and permission to be direct.

So far so good, but wringing our hands like this is depressingly negative. What we need are practical suggestions to avoid these problems in the first place. Orwell obligingly offers up six questions he suggests every author should ask while writing:

•What am I trying to say?

•What words will express it?

•What image or idiom will make it clearer?

•Is this image fresh enough to have an effect?

•Could I put it more shortly?

•Have I said anything that is avoidably ugly?

Now we’re getting to the heart of why you should bother with Orwell and his ancient essay. These questions are simple, obvious even, but that’s the point. Good copywriting isn’t an arcane, mystical process; it’s the result of applying simple principles with consistency.

Toyota’s straightforward, clear, and concise campaign for the Yaris.

Orwell goes as far as to say that pretty much all political writing (or in our case copywriting) is bad. On those rare occasions when this isn’t the case, Orwell believes the writer must be a rebel, someone with sufficient independence of mind to express “his private opinions” and “not a party line.” As he puts it, “Orthodoxy, of whatever colour, seems to demand a lifeless, imitative style.” Indeed it does. In this book we encourage you to reject the lifeless conventions Orwell criticizes and embrace a vivid, accurate style that touches people’s hearts and minds. You may be familiar with this:

Here’s to the crazy ones. The rebels. The troublemakers. The ones who see things differently. While some may see them as the crazy ones, we see genius. Because the people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world, are the ones who do.

It’s the main message in TBWAChiatDay’s classic 1997 “Think different” campaign for Apple, and about as far from orthodox business writing as it’s possible to get. As well as its rousing content, just look at the short words and tight sentences. Orwell would have approved of the ad’s prose, although perhaps not its purpose.

By now you may be thinking that Orwell is dangerously close to becoming some sort of nitpicking pedant. Not so. In fact Orwell specifically states he’s not interested in “correct” grammar and syntax, “which are of no importance so long as one makes one’s meaning clear.” Nor is he bothered about avoiding so-called Americanisms or enforcing what might be called a good prose style. He doesn’t want to encourage “a fake simplicity,” or the misguided belief that shorter words are always better than their longer equivalents (that’s usually the case, but there are always exceptions). Orwell is simply saying we should “let the meaning choose the word, and not the other way around.” This is the very heart of his argument and might be summarized as express yourself in words that are right for your task.

How exactly? Well, first think about what you’re trying to say, and then do as Orwell suggests and “switch round and decide what impressions one’s words are likely to make on another person.” That last part is crucial for copywriters. We write exclusively to make an impression on others, and here Orwell is telling us how to do it. As he puts it, “This last effort of the mind cuts out all stale or mixed images, all prefabricated phrases, needless repetitions, and humbug and vagueness generally.”

Apple’s classic “Think different” ad, created by TBWAChiatDay in 1997. By the end we practically want to leap up and shout, “Yes, YES! THAT’S ME! I’m CRAZY and PROUD! Where do I sign?”

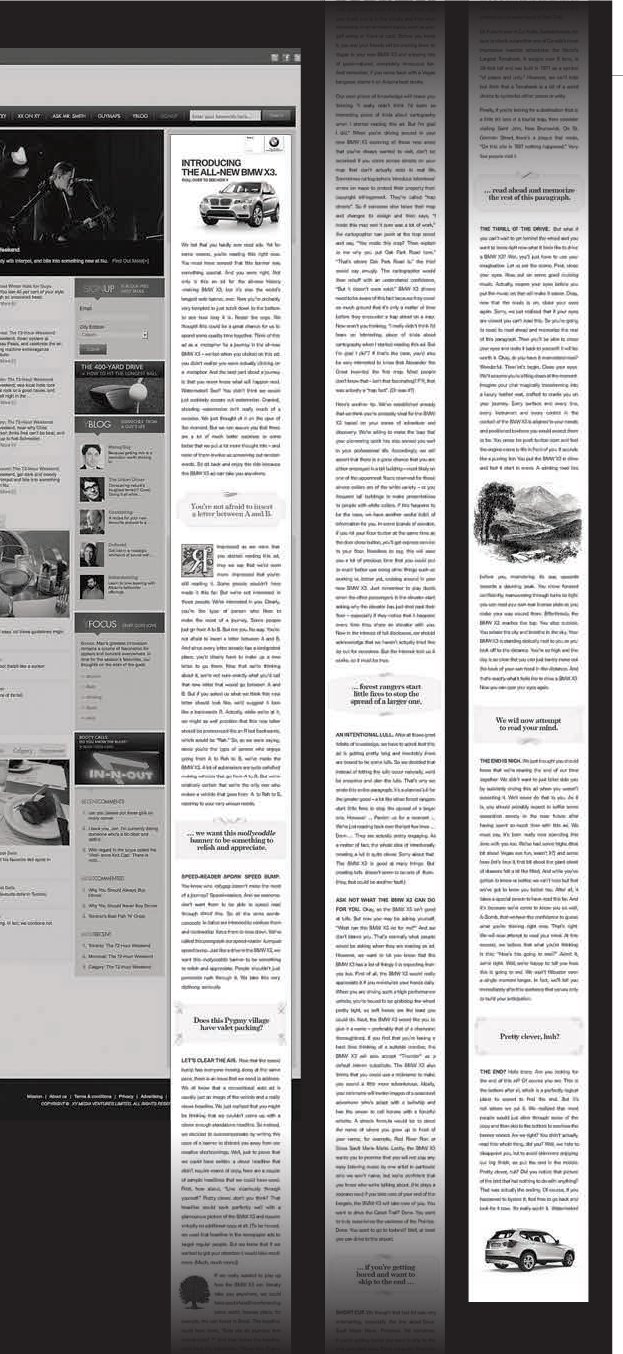

The world’s longest banner ad. Gleefully ignoring Orwell’s advice to cut out every unnecessary word helps this playful ad for BMW draw attention to itself.

To help us he provides his famous six rules (a sort of counterpoint to the six questions suggested earlier), the most quoted and reproduced part of his essay. Here they are:

•Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

•Never use a long word where a short one will do.

•If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

•Never use the passive where you can use the active.

•Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

•Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

There’s nothing magical about these. Orwell acknowledges that it’s perfectly possible to write bad English using them, but not the sort of bad English we’ve described here with its windy vagueness, shoddy imagery, and lack of meaning.

In the final paragraph of his essay Orwell states:

If you simplify your English, you are freed from the worst follies of orthodoxy. You cannot speak any of the necessary dialects, and when you make a stupid remark its stupidity will be obvious, even to yourself.

In other words, keep it simple and any shortcomings in your work will be obvious. The result will send the “verbal refuse” of so much writing “into the dustbin, where it belongs.” Amen to that.

Orwell’s English in 30 seconds

Ask yourself these six questions:

•What am I trying to say?

•What words will express it?

•What image or idiom will make it clearer?

•Is this image fresh enough to have an effect?

•Could I put it more shortly?

•Have I said anything that is avoidably ugly?

Follow these six rules:

•Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

•Never use a long word where a short one will do.

•If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

•Never use the passive where you can use the active.

•Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

•Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

Orwell’s six questions and six rules are solid gold, but only if you actually put them to use. Reading them through, nodding approvingly, and then forgetting about them as the pub beckons isn’t exactly the path to enlightenment. To help embed Orwell’s ideas in your brain we’ve come up with a couple of exercises we think are worthy of your attention.

Workout One

A prospective employer wants you to write a few paragraphs explaining why they should invite you for an interview.

First write your reply as you would normally (don’t overthink it— just do what comes naturally). Once you’re finished, rewrite it using Orwell’s six questions and six rules to ruthlessly assess and improve every word and sentence. Which version is better? Why?

Workout Two

Find a speech or other piece of public writing that seems stuffed with pretentious diction, meaningless words, cloudy vagueness, and so on (any halfway decent library will have plenty of anthologies of speeches by the great and good, as does the Web).

Go through your chosen speech (or a section if it’s too long) and tease out the real meaning as a list of bullet points. Next use Orwell’s six questions and six rules to rewrite it so the text is clear and sparkling “like a windowpane.”