Not Telling Stories, Selling Stories

The power of narrative to convince by stealth

The storytelling party, from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll.

In her 1968 poem “The Speed of Darkness,” the poet Muriel Rukeyser wrote, “The universe is made of stories, not of atoms.” It’s a lovely image, suggesting life is the sum of the tales we tell. It’s also pretty accurate—we’re hardwired to rework events into a coherent narrative as we attempt to understand the world. So come with us as we explore how stories can help copywriters communicate with power and personality. Are you sitting comfortably? Then we’ll begin…

The Globe Theatre, Southwark, London, 1599, about teatime. A group of players assemble on stage, among them William Shakespeare, the chap responsible for tonight’s entertainment. Instinctively the groundlings quieten down and the fruitsellers mute their cries. As hush descends, the scene begins:

Now is the winter of our reduced sales forecast, Seasonally adjusted to reflect adverse trading conditions.

An apple core hits Richard III right between the eyes —shot! Another causes the Duke of Clarence to dodge, knocking the ghost of King Henry VI to the ground in a clatter of stage armor. The crowd roars in delight and the attack intensifies, their displeasure all too apparent. This isn’t what they paid to see…

Needless to say, this surreal scene never happened. Then, as now, what theatergoers want—what we all want—are stories, because stories are an important part of what it is to be human.1 If you’re trying to get through to people, the cant and cliché of business-speak is the biggest turn-off imaginable. You won’t be pelted with rotten fruit but you will be ignored—which in our line of work is just as bad.

From a copywriting perspective stories matter because they’re fun and functional at the same time. Fun because they’re naturally appealing and we’re primed from birth to accept information presented in narrative form; functional because they’re powerful explaining tools that enable us to describe the who, what, where, when, why, and how of a subject without seeming to. That’s why stories are important and that’s why every copywriter needs to know when and how to switch into storytelling mode.

The scene.

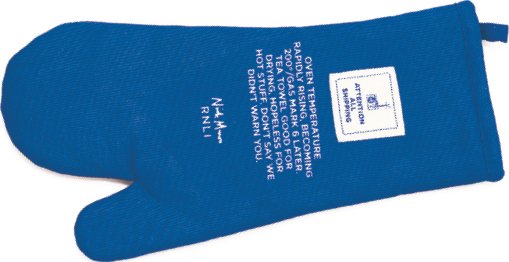

“Attention all shipping” are the first words of BBC Radio’s Shipping Forecast, a weather bulletin covering the seas around the British Isles. Over the decades the Shipping Forecast has become famous for its measured pace, hypnotic delivery, and evocative place names (“Shannon, Rockall, Malin, west 8, occasionally 9, becoming cyclonic later…”). These microstories—written by Roger—twist the Shipping Forecast’s distinctive language to suit a series of domestic situations vaguely connected to various items of homeware— appropriate enough, given the client is the Royal National Lifeboat Institution, the charity that runs the UK and Ireland’s lifeboat service.

What exactly do we mean by “stories”?

In this context “story” refers to anything from a short anecdote to a lengthy tale. It probably doesn’t begin “Once upon a time,” although brand stories (as we’ll call them) often include features we associate with literary stories. For example, many brand stories feature some sort of hero who struggles with some sort of antihero, leading to resolution and a happy ending where everyone goes home wiser. What matters is the effect, not the word count or format. For us, brand stories are about creating engagement. The good news is that shouldn’t be too hard to achieve, as stories are engagement machines par excellence.

Like any good story, a brand story should be clear, compelling, and built around a strong central idea. If it isn’t clear then no one will learn anything meaningful, if it isn’t compelling then readers will drift off halfway through and start thinking about lunch, and if it isn’t built around a powerful main theme then your audience will be left wondering what point you’re trying to make.

Another important feature is struggle or difference. Aristotle suggested that, “The essence of drama is conflict.” It’s exactly the same here—if a brand story contains even a whiff of tension it’ll become more readable and memorable as a result. It also needs to feel grounded in reality—if a brand story couldn’t possibly be true then it’s fantasy, not copy. The trick is to use a story vivid enough to embed itself in the readers’ imagination, yet real enough to touch on or illuminate some relevant truth.

Of course stories like this demand the right sort of language; they need to use human words and focus on human themes. That’s the way to establish an emotional connection with your audience, and emotional beats rational every time. Here “story” is almost a synonym for “brand,” as the next section explains.

This pastiche playbill for the University of Lincoln Creative Advertising degree end-of-year show uses multiple ministories to enthrall and entertain.

Brand stories are a particularly effective way of explaining an organization’s origins. Consider this example from hyper-successful UK smoothie-maker Innocent. It comes from their company rule book:

In the summer of 1998 when we had developed our first smoothie recipes but were still nervous about giving up our proper jobs, we brought £500 worth of fruit, turned it into smoothies and sold them from a stall at a little music festival in London. We put up a big sign saying “Do you think we should give up our jobs to make these smoothies?” and put out a bin saying “YES” and a bin saying “NO” and asked people to put the empty bottle in the right bin. At the end of the weekend the “YES” bin was full so we went in the next day and resigned.

It’s a modern-day creation myth—only it happens to be true. Don’t you feel instant affection for Innocent’s fruit-loving founders? In 110 words they manage to explain when and how it all began, tell us something about their attitude to life and business, locate themselves culturally, and give us a glimpse into their organization’s soul, a notoriously intangible subject that often defies direct description.

Then there’s the story of how Nike cofounder Bill Bowerman poured liquid latex onto his wife’s waffle iron to create a grippy sole for a new sneaker he was developing at home. That sounds suspiciously fabricated until we learn that during a house clearance in 2010 Bowerman’s daughter-in-law, Melissa, found the actual waffle iron her late father ruined in 1970, and presented it to Nike. It seems Bill really did cook up a load of molten latex in his kitchen before using it to create a high-traction running shoe and—as a welcome byproduct—one of the world’s most successful companies.

Now see what you think of this creation myth by John Simmons. It describes a tense moment in the real-life history of Guinness, when Dublin’s civic authorities tried to block the company’s access to the city’s water supply—important stuff for any brewer. Look at the language, in particular the unusual word choices (“expletives,” “sanctify,” “girth”) and the wordplay (“stout gentleman”—Guinness is of course a stout). Look at the structure, in particular how it begins in the middle of the action (a technique we recommended back in Lesson Three). It’s not what you’d expect from a big corporate, yet the result works wonderfully well and illustrates the difference between a dry history and an engaging brand narrative:

Bill Bowerman, one of the prime movers behind Nike.

Innocent company rule book, which in typical Innocent fashion doesn’t contain any rules.

The story starts with the expletives deleted. We don’t need to sanctify the memory of our founder but no one ever recorded the swear words Arthur Guinness flung across the barricades at the gentlemen from the Dublin Corporation in 1775. But fling them he did.

The temptation is to describe Arthur Guinness as a stout gentleman. Well, we make no point about his girth but we do know Arthur Guinness took his time before he came around to brewing porter. When he finally did, it was worth waiting for.

This microstory explains that Honda’s Swindon factory is back in action, and that means good times for local businesses. Notice how they’re promoting a brand, not a product.

This inviting TV ad for Honda is based on a true story. One of Honda’s lead engineers— a chap called Kenichi Nagahiro—hated diesel engines because they were smelly, noisy, and bad for the environment. So when he was asked to design one he took the opportunity to create something much kinder on the eyes, ears, and nose—not to mention nature.

But it was water that did it. The whole history of Guinness is built on water.

Think of that the next time you sink a pint. If Arthur hadn’t made his first stand against the bureaucrats and stood up for his commercial rights we wouldn’t be here now thinking of new ways to fight the Guinness cause.

“I did a deal, dammit, so let’s stick to it!”

Arthur Guinness stuck to it. It took him twelve years to win his fight for the Dublin water rights, but he won. And that was the first crucial turning point in the story of Guinness.

It takes strength to do it. Not necessarily the girder-lifting strength of a strongman, but the commitment that comes with an inner certainty.

Think about it. Savour it. And lift your glass to Arthur. We owe it to him.

Founding stories like this are effective because they humanize a brand’s beginnings. They describe how one or more spirited individuals overcame adversity to achieve fortune and glory, so they’re about belief, vision, and maybe a little drama. In other words, they talk about business in nonbusiness terms. This ability to create emotional resonance is the brand story’s greatest asset. We read and remember because we enjoy. No wonder stories are such effective communication tools.

If you want to be a writer, here’s what I have learned after 20 years of being a journalist/author/copywriter. And I don’t say this as someone who has reached a point of arrival. Even when you’re at the top of your professional game you will never stop learning.

1. Man up. It takes a tough cookie not to mind your work being torn to bits and reconstructed from scratch. Deal with it, it will happen everyday.

2. What you think is good/acceptable may not be to others. You might love your fiber-optic Santa Claus, but it might make other people roll their eyes and stick their fingers down their throats. Same goes for words. Think about your writing objectively, from the reader’s point of view.

3. Look around you. Writers don’t exist in a vacuum. Read books, consume media, be a fan of other people’s work (but don’t copy it). Talk to other writers. They’ll probably be able to give you better advice than this.

4. Enjoy it. Words are beautiful! Be creative, and weave them together to create wonderful new worlds. Whether it’s a leaflet or a novel, every word is important. If you love writing, people will want to read your work.

5. Just do it. Be there, everyday, and don’t give up. Develop your writing like Rocky developed his muscles—I’m thinking a shot of you sitting at the laptop with sweat dripping onto your keyboard. OK? GO! DO IT NOW! WRITE SOMETHING!

Lucy Sweet was born in Hull in 1972 but she hasn’t let that stop her. Her first writing job was for Melody Maker aged 19, and since then she has been a freelance journalist, writing columns and features for such diverse publications as the Sunday Express, Daily Record, Glamour, The Guardian, New Statesman, and Reveal. She is also the author of two novels published by Corgi, as well as the creator of Chica, an award-winning magazine for girls, and Unskinny, a cartoon anthology published by Quartet. After three years as an advertising copywriter, Lucy now writes about parenting, luxury travel, and fashion for the Web, and is the author of the 2013 Louis Vuitton Guide to Glasgow.

Just as every organization has a brand (a point we’ll expand on in the next lesson), so every brand has a story—probably many, many stories. Making a conscious effort to tell these tales in an appropriate way isn’t PR puffery, it’s an effective way for a company to connect with its public and make itself understood, remembered, and maybe even liked.

The key point for copywriters is that a well-chosen story gives a brand something worthwhile to say. That’s true for both business-to-business and business-to-consumer communications (often shortened to B2B and B2C). After all, business customers are still human and make buying decisions for emotional as well as rational reasons despite what they might say—stories just help them decide. The lesson is simple: if you’re stuck for an angle, search for a story.

Find, don’t invent

So how do you go about writing a brand story? The short answer is, you don’t. You can’t really create stories like these, you can only uncover them.

To do that you need to dig until you find an anecdote with reader appeal that says something worthwhile about your subject. This digging—the sort of thing journalists do every day—can feel like a thankless task; the only good news is that because you find rather than invent brand stories, if/when you strike lucky, then what you’ve found must be true.

The point is, stories like the Innocent creation myth are unlikely to be just sitting there waiting to be noticed. It’s doubtful that during your first meeting with a client they’ll blurt out something quirky and fascinating about how the business began, or how their latest product came to be. By all means ask outright if they’ve anything approaching a suitable story—you might get lucky. However, the chances are you’ll have to do some serious research, which in practice means speaking to lots of people and panning for gold in their replies.

Even that apparently simple process can be fraught with difficulties. If you’re inexperienced or lack clout with the client then getting access to knowledge holders can be hard. Your best bet is to enlist the support of a senior figure. Explain what you’re trying to do, why it matters, and how they can help by pointing you in the right direction. Ideally you can use their name to get the attention of hard-to-reach members of staff, perhaps using a subject line like “XXXX suggested I get in touch” for your introductory e-mail. Explain why you need their help and how important their contribution might be. A touch of mild flattery never goes amiss.

The instruction that writers should avoid clichés has, naturally, become a cliché itself. It is a maxim with so many exceptions that apply to anyone with wit or a sense of style that it has performed a very special kind of literary self-immolation.

The accompanying plea that you should “write about what you know” has, however, never been more relevant. Every form of writing, from novels to Web content, and from ad copy to journalism, can benefit from your voice, your knowledge, your tastes, and your authority.

This doesn’t mean sticking “I” into the copy at every opportunity. If we wanted to read about you that much we would look at your Facebook timeline and flick through the 874 pictures of yourself that you have tagged.

What you need to instill in your writing is that element of your character that makes you memorable, makes your mates keep inviting you out, and makes your partner tell you they love you every so often. Others may put this special something down to your winning smile, your effortless charm, or your sense of humor, but the truth is that it’s closer to something that the religious (myself not among them) may call your soul. It is the thing that makes you—and your writing—unique.

So every time you read back what you have written, ask yourself, “Have I put something of myself into this?” If the answer is “no” then edit and rewrite until you can honestly say “yes.” Any fool can type. But writing takes soul. Your own.

Iain is a journalist and author based in London. He’s written two books for major publishers, along with articles for The Times, Financial Times, Daily Telegraph, and The Guardian (where his piece on rockney legends Chas ’n’ Dave was voted Article of the Year by readers). Iain is the London editor for achingly hip Dwell magazine, and has contributed to Art World, American Craft, Coast, Dazed & Confused, Livingetc, Olive, Vegetarian Living, The Idler, and Bizarre. Iain writes copy for a number of corporate clients and is an enthusiastic blogger.

Story checklist

You’ve found a candidate story— congratulations. Now ask yourself:

•Is it interesting, memorable, and believable?

•Could someone recognize the brand based on just the story?

•Is it right for the brand’s audience? Will they get it?

If you can answer “yes” to all three then you’re onto something.

Turning descriptions into stories

What do you do if you really can’t find a story to suit your purposes? You do the next best thing, which is to turn a straight description into an intriguing tale. How do you do that? Here’s how.

Consider the following chunk of text borrowed from an imaginary webpage for an imaginary chain of upmarket supermarkets:

We aim to develop our people at every opportunity. We’ve a fantastic track record of helping staff improve their skills through accredited training courses in everything from butchery to baking, produce to personnel, and management to marketing. This creates a breadth and depth of experience that keeps our customers coming back.

It’s the sort of thing you see all the time in the corporate world. The from/to device—repeated three times—gives the piece a decent structure and shows the breadth of the company’s business. It’s perfectly well written, yet we sense a missed opportunity. Surely some or all of it could have been presented in story format for added impact? With that in mind here’s our reworked version:

We do everything we can to help our staff become the best they can be. For example, we made sure Ben Jones in our Oxford store had the opportunity to train as a Master Butcher, which meant he could proudly display his graduation certificate as proof of his expertise, which meant Mrs. Lynn Manning decided to buy her meat from us this week instead of her usual butcher, which meant her husband Malcolm had some expertly trimmed pork chops for his dinner, which meant no gristly bits for Musky, their Jack Russell terrier. Sorry, boy!

We’re certainly not suggesting this remix is the solution; instead we’re saying that by making it specific, human-orientated, and image-intensive it becomes more storylike, with all the benefits that brings.

It’s the same with this (fictional) paragraph taken from (fictional) MajorMining Corp’s website:

Think about the electronics in your home. The chances are they include metals and minerals mined by us. That includes copper for circuit boards, gold for connectors, and silicates and rare metals used in microelectronics. At MajorMining we locate and refine the raw materials that make modern life possible.

Like the supermarket piece above it’s adequate but underwhelming. And again, like the earlier example it can be usefully reworked into something more storylike, in this case by introducing human-interest specifics that show how MajorMining’s products are an unseen part of everyday life:

That call you made to wish your mom Happy Birthday—we found and refined the copper that made it possible. Your train journey to work—zinc from our mine in Canada keeps the engine’s chassis rust-free. Your new laptop? It wouldn’t work without the rare metal palladium from our site in Australia. Your TV and DVD player? Us again. Your kids’ game console, your partner’s tablet device, your car’s electronics…well, you get the idea. We are MajorMining, and what we do makes modern life possible.

Our point is that most organizations’ copy feels flat because it fails to establish any sort of one-to-one connection with its readers. As a result there’s nothing to engage the emotions or fire the imagination. That’s a mistake. Strip away the hoopla and all businesses are just one group of people doing stuff for another group of people—human to human. Put it like that and presenting an organization’s story as a story makes perfect sense. In fact it’s crazy to do anything else.

Classic ads from Avis. Note how writer Julian Koenig uses detail to create appeal—it’s the classic “tell it to sell it” combo. The closing couplet of “Go with us next time. The line at our counter is shorter” must be one of the best ad endings ever written.

It’s impossible to read Vespa’s cool, evocative copy and not start filling in the gaps to create our own personalized story of a life less ordinary.

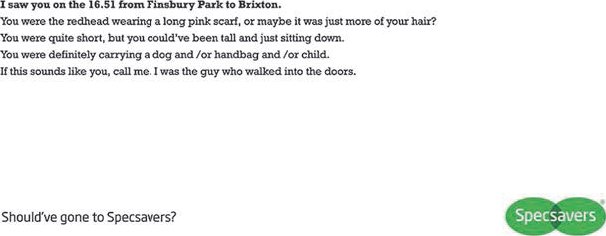

A lovely little story for an opticians that makes its point with economy and charm. Can’t you just see it (no pun intended)?

These three nuggets of practical advice will hopefully serve you well:

Clients don’t always know best when it comes to creative (and it’s quite annoying when they do). That means you’ll need the confidence to stand by your concepts and your copy (assuming they’re good enough, of course) but, just as importantly, you’ll need to know when it’s counterproductive to argue your case. This judgment will come in time—there’s no substitute for experience.

Play it simple. Don’t try too hard when it comes to the actual words. It’s tempting to use the big words, the clever phrasing, the copywriting equivalent of the “Hollywood Ball”... but you often won’t need it. Sometimes, the hardest thing can be accepting that the easiest solution is the right solution.

Finally, remember that Woody Allen quote: “90 percent of success is just showing up.” So make sure you do. On time.

David began his writing career at super-trendy style magazines The Face and i-D during the 1990s, alongside some glamorous travel writing for Condé Nast Traveller and the Sunday Telegraph, among others. Today he’s an award-winning copywriter and brand consultant who specializes in corporate tone of voice and works for global clients and advertising/design agencies across the UK.

A suite of stories for Mercedes-Benz trucks, riffing on the theme of oil. They build nicely to the final page, where the point of the piece— promoting Mercedes’ BlueTEC clean diesel technology—becomes apparent. A surprisingly playful approach for a direct marketing piece aimed at hard-nosed trade buyers.

Lack of confidence is the killer when it comes to brand storytelling. Everyone involved is worried about making a fool of themselves and ruining the brand’s carefully nurtured reputation. We’ll have no such nonsense here. Instead we beseech you to be big, bold, and brilliant. That’s a lot to ask, especially if you’re a rookie, but the following exercises should get you started. As always in our world, the best way to convince doubters is with great work.

Workout One

First take a piece of real brand copy and rework it as a story. The copy can come from any source but the brand’s website, particularly the “about us” section or equivalent, is a good place to start. Industry or sector is irrelevant—instead focus on finding a reasonably detailed description of some aspect of the brand’s purpose or activity. Once you’ve found a paragraph or three you like, try putting it/them into the first person—I or we—and add as much imaginary extra detail as you need (remember, it’s only a workout). aim for something that adopts the same human-to-human approach as our examples above.

Workout Two

Now take things further—a LOT further. In his landmark book The Seven Basic Plots, uK author Christopher Booker explains, well, the seven basic plots of all literature. We’ve summarized them below. We want you to rework your piece from Workout One using one of these while keeping as much detail as you can. Don’t play it safe—have some fun and see how far you can take it while still retaining a useful link to your source material. at what point does the connection break down?

The seven basic plots of all literature

OVERCOMING THE MONSTER

Hero learns of a great evil threatening the land and sets out to destroy it. Examples: Terminator, Jaws, The Magnificent Seven, any James Bond, any monster/slasher movie.

TRAGEDY

The flip side of “Overcoming the monster.” Our character is the villain, and we watch as he slides into darkness before being finally defeated, freeing the land from his evil influence. examples: Hamlet, Macbeth, The Lord of the Rings, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde .

REBIRTH

Like the “Tragedy” plot, but the main character manages to realize his error before it’s too late, thus avoiding inevitable defeat. Examples: Star Wars, Sleeping Beauty, Snow White .

LOSER TO WINNER

Surrounded by dark forces who suppress and ridicule him, the hero slowly blossoms into a mature figure who ultimately gets riches, a kingdom, and the perfect mate. Examples: “rudolph the red-Nosed reindeer,” harry Potter, David Copperfield, Cinderella, Aladdin.

THE QUEST

Our hero learns of some lost beautiful thing he desperately wants to find, and sets out to find it, often with companions. Examples: The Hobbit, Watership Down, any Indiana Jones, anything to do with the grail legend.

VOYAGE AND RETURN

Our hero heads off into a magic land with crazy rules, ultimately triumphs over the madness/badness he finds there, and returns home a little wiser than when he set out. Examples: Alice in Wonderland, The Wizard of Oz, Where the Wild Things Are, pretty much any Dr Who episode.

COMEDY

hero and heroine are destined to get together but a dark force prevents them from doing so. Somehow the dark force repents and the hero and heroine are free to get together, at which point everyone is revealed as who they really are, allowing other relationships to form. Examples: Four Weddings and a Funeral, Much Ado About Nothing, anything by Jane austen.

1. In his book The Storytelling Animal, Jonathan Gottschall suggests this is because we use story as a sort of mental flight simulator, enabling us to try out situations, characters, emotions, and outcomes without all the dangers and difficulties associated with doing the same in real life.