Evaluation Design

As mentioned previously, there is no single approach to designing and conducting evaluations. Each is tailored to a specific program's particular context, mandates, and potential uses. “Evaluations should be based on the content, purpose, and outcomes of the program, rather than being driven by data collection methodologies” (Lapan, 2004, p. 239). As such, evaluation research uses multiple sources and methods of data collection and analysis. These may generate both quantitative and qualitative data. In any case, evaluators should design and carry out studies that meet the AEA (2004) principles and standards (see Table 13.1) for ensuring high-quality evaluations.

As compared to case study research, which focuses either on thorough descriptions of programs or on building and validating theories from multiple case studies (see Chapter Ten), the hallmark of an evaluation is the determination of criteria for judging the quality of a program, with standards of performance clearly explained. In his article with theater critic Charles Isherwood, Alastair Macaulay, the chief dance critic for the New York Times, explains,

We're critics: our first task is not to determine what big-theater audiences will like but what we think is good and why. We're critics because we have criteria and we use them: different criteria on some occasions, but serious criteria to us. Sometimes we're both going to object strongly to shows that we can see are very popular indeed; sometimes we're both going to enthuse passionately about productions that leave most people cold. (Isherwood & Macaulay, 2010, p. C1)

This evaluation process is different from informal reviews and critiques in that the criteria and standards are predetermined, unlike an ad hoc critique: “I just like this show, and I don't like this other one.”

Selecting Criteria to Study

Central to the selection of criteria for an evaluation are two questions: What is the purpose of the evaluation? and Who needs to know the information provided? A source to identify possible criteria for a program evaluation is often the program's logic model or detailed description.

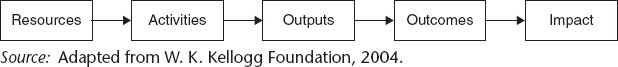

Whether formalized into a written document or implied by program goals, objectives, activities, and outcomes, a logic model provides a graphic representation for understanding how a program works (see Chapter Fourteen for one example). This includes the theory and assumptions that underlie the program. A logic model is “a systematic and visual way to present and share your understanding of the relationships among the resources you have to operate your program, the activities you plan, and the changes or results you hope to achieve” (W. K. Kellogg Foundation, 2004, p. 1). More and more funding agencies, including private foundations and government offices, require a logic model as part of a grant proposal.

According to the W. K. Kellogg Foundation (2004), at its most basic level a logic model includes five components:

- Resources and inputs—human, financial, organizational, and community

- Activities—processes, tools, events, technology, actions, and interventions

- Outputs—products of the activities, including types, levels, and targets of services delivered by the program

- Outcomes—changes in program participants' behavior, knowledge, skills, status, and level of functions, both short-term (within 1 to 3 years) and long-term (within 7 to 10 years)

- Impact—fundamental intended or unintended change in organizations, communities, or systems as a result of program activities over the long term

This is most commonly represented as a simple linear sequence (see Figure 13.1), although it is also possible to create much more complex logic models that include theories of change.

An evaluator uses a logic model to assist stakeholders in determining the criteria that are critical to evaluate a program's design, implementation, and results. Examples of criteria from an unemployment support services program logic model might include financial assets and program staff (resources), daily program operating procedures (activities), information events or training sessions delivered (outputs), participants' employment status and job performance (outcomes), and unemployment rate trends in the community (impact).

If no written logic model exists, evaluators, with the stakeholders, first write a detailed program description that provides essentially the same information. By examining program documents and talking to the program stakeholders, evaluators identify a program's antecedents, intended transactions, and expected outcomes and impact. Often these interactions with the program stakeholders can also result in the creation of a program logic model.

Stufflebeam and his associates at the Evaluation Center of Western Michigan University conducted an evaluation of the Consuelo Foundation's Ke Aka Ho'ona project between 1994 and 2001. This initiative was a self-help housing project in which low-income families worked together, under the supervision of a licensed contractor, to construct their own homes in the Honolulu (Hawai'i) County community of Wai'anae. Their evaluation included a report on the program's antecedents, a second report on its implementation, and a third report on the project's results (Stufflebeam, Gullickson, & Wingate, 2002). These were the three goals for the project (p. 22):

FIGURE 13.1 Simple Logic Model

- Build a community of low-income working families with children who commit to live in and help sustain a nurturing neighborhood free from violence and substance abuse and devoted to helping others.

- Increase Wai'anae’s supply of affordable housing

- Develop a sound approach to values-based, self-help housing and community development

In this section of the chapter I will use the third report to provide examples of designing and implementing an evaluation study. All of the evaluation reports for this program are available from the Evaluation Center Web site, listed at the end of the chapter. Exhibit 13.1 identifies the criteria selected for the evaluation of the Ke Aka Ho'ona project.

Forming Study Questions

Once the criteria for the evaluation project are identified, the development of specific study questions follows. These may be predetermined, such as when a program's source of funding requires answers to specific questions. These most likely will emphasize accountability: the effectiveness (in terms of costs, benefits, and services) and the impacts of the program (for example, improved student achievement scores, reduction in the rate of recidivism for paroled prisoners, increased voter turnout for primary elections). The purpose of these types of research questions is summative, used for making judgments after the program is complete for the benefit of an external audience or decision maker (Scriven, 1991).

EVALUATION CRITERIA FOR THE KE AKA HO'ONA PROJECT

The use of the CIPP Evaluation Model provided a comprehensive assessment of the Ke Aka Ho'ona project for the Consuelo Foundation's board of directors and other stakeholders. The model includes assessing the

- Context, the nature, extent, and criticality of beneficiaries' needs and assets and pertinent environmental forces (adherence to Foundation values and relevance to beneficiaries)

- Input, including the responsiveness and strength of project plans and resources (state-of-the-art character, feasibility)

- Process, involving the appropriateness and adequacy of project operations (responsiveness, efficiency, quality)

- Product, meaning the extent, desirability, and significance of intended and unintended outcomes (viability, adaptability, significance)

Source: Stufflebeam et al., 2002, p. 65.

Other program stakeholders, including managers, staff, and sometimes recipients, may choose to ask questions that determine information for improving the program, often called formative evaluations. Patton (1997, p. 68) provides these examples of formative questions:

- What are the program's strengths and weaknesses?

- To what extent are participants progressing toward the desired outcomes?

- What is happening that wasn't expected?

- How are clients and staff interacting?

- What are staff and participant perceptions about the program?

- Where can efficiencies be realized?

Table 13.2 Evaluation Questions for the Ke Aka Ho'ona Project

For a long-term program such as the Ke Aka Ho'ona project, over time both formative and summative evaluations provided feedback during the program to help the Consuelo Foundation leaders and staff strengthen project plans and operations. The final summative report appraises what was done and accomplished. The Evaluation Center used the CIPP Evaluation Model to carry out this long-term study. The main questions that guided the study are shown in Table 13.2.

Selecting Standards

Once the specific criteria for the evaluation are identified, clearly identifying its purpose and audiences, and the questions are developed, evaluators determine appropriate standards by which to measure program quality, value, or success. These may be predetermined by the program's funding agency or developed in collaboration with one or more of the program's stakeholders. The following are the standards for the CIPP evaluation of the Ke Aka Ho'ona project (Stufflebeam et al., 2002, p. 66):

- Positive answers to the evaluation questions would rate high on merit, worth, and significance.

- Negative findings to any of the evaluation questions indicate areas of deficiency, diminishing judgments of program soundness and quality, and possibly discrediting the project entirely.

- Failure to meet the assessed needs of the targeted beneficiaries indicates overall failure of the project.

Data Collection

Evaluations can and should generate both quantitative and qualitative data by incorporating multiple types of instruments (data collection tools) and multiple sources of information. Just as in case studies (see Chapter Ten) and the other research methodologies in this text, the questions determine which instruments (such as tests, questionnaires, observations, or interviews) should be carefully selected, adapted, or developed to generate useful and valid data (see Chapter Four).

Similarly, the study questions also imply the best sources of data (such as documents, program staff, or recipients of services). Unlike quantitative methodologies, evaluations do not usually incorporate random sampling (also called probability sampling) to select a small group of study participants, because evaluators are not trying to generalize results as representative of a specific population. Rather, evaluators are more concerned with maximizing the representativeness of information. They therefore seek out people who can best answer each kind of question; this is known as purposeful (or purposive) sampling. This process is similar to collecting data in ethnography (see Chapter Seven) and case study research (see Chapter Ten), for which key informants who have the most information are actively sought. It is also most desirable to seek out alternative views and incorporate these into the results of the evaluation.

For the Ke Aka Ho'ona project, multiple methods were used to gather data; each part of the CIPP Evaluation Model incorporated at least three different data collection methods, as is evident in Table 13.3.

Data Analysis

Evaluators use the same data analysis strategies as other researchers. Because of the multiple types of data collected, evaluators must develop skills in coding and synthesizing qualitative data (see Chapter Three) and in descriptive and inferential statistics for quantitative data. I refer you to statistical texts or other quantitative research resources (such as Lapan & Quartaroli, 2009, or the Research Methods Knowledge Base online at www.socialresearchmethods.net/kb/) for further information.

Table 13.3 Data Collection Methods for CIPP Evaluation of the Ke Aka Ho'ona Project

According to Patton (1997), there are four distinct processes involved in making sense of evaluation findings. The first task is to organize the data into a format that makes evident any basic patterns or relationships. For example, evaluators can create concept maps, tables, frequency diagrams, and flow charts to illustrate and summarize the data. Once this is accomplished, the evaluators must make interpretations of the data: “What do the results mean? What's the significance of the findings? … What are possible explanations of these results?” (p. 307). Next, the key component of evaluation is addressed: What is the merit, value, or worth of the program? In what ways are the results positive, and in what ways are the results negative? How do the results compare to the standards selected for the evaluation? A final step is likely to be included, although it is not mandatory: What action or actions should be taken in regard to the program? Often these are presented as a list of recommendations.

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

- For the programs that you identified for evaluation, what might be important formative evaluation questions to answer? Summative questions?

- Considering the formative and summative questions you have written, what data collection methods and sources would most likely provide the most useful and diverse data?

Reporting Study Results

Many if not most evaluation reports are submitted to the program management or funding agency without being published in the research literature. An evaluation report often includes an executive summary, or the summary of findings in brief. It may also articulate “recommendations for changes or … program elements that should be supported or receive greater emphasis” (Lapan & Haden, 2009, p. 193). The report should also provide specific details about the program, including a thorough description of the context for the evaluation and the evaluation design (data collection methods, sources, analyses, and syntheses of findings). Alternative views about the program's quality are also incorporated into the final evaluation report as part of what is often called a minority report.

The dissemination of findings to different stakeholders and audiences may require different formats and vocabulary. Most often the results are presented in writing, but other visual formats (such as multimedia videos or slide shows) may be appropriate, depending on each audience's expectations, levels of understanding, and language competencies.

Throughout the Ke Aka Ho'ona project (see Table 13.3) the evaluation team held feedback workshops with project leaders and staff, as well as with other stakeholders invited by the Consuelo Foundation, to go over draft reports. The workshop participants discussed the findings, identified areas of ambiguity and inaccuracy, and updated evaluation plans. A similar process occurred with the draft composite report before it was finalized in 2002.