Chapter 11

Aligning the Key Players for Your Project

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Comparing the pros and cons of three organizational structures

Comparing the pros and cons of three organizational structures

![]() Defining the actors and their roles in the matrix structure

Defining the actors and their roles in the matrix structure

![]() Being successful in a matrix organization

Being successful in a matrix organization

In the traditional work environment, you have one direct supervisor who assigns your work, completes your performance appraisals, approves your salary increases, and authorizes your promotions. However, increasing numbers of organizations are moving toward a structure in which a variety of people direct your work assignments. What’s the greatest advantage of this new structure? When all is said and done, it supports faster and more effective responses to the diverse projects in an organization.

Success in this new project-oriented organization requires you to do the following:

- Recognize the people who define and influence your work environment.

- Understand their unique roles.

- Know how to work effectively with them to create a successful project.

This chapter helps you define your organization’s environment and understand individual roles. It also provides tips to help you successfully accomplish your project in a matrix organization.

Defining Three Organizational Environments

Over the years, projects have evolved from organizational afterthoughts to major vehicles for conducting business and developing future capabilities. Naturally, the approaches for organizing and managing projects have evolved as well.

This section explains how projects are handled in the traditional functional structure, the project-focused projectized structure, and the extensively used matrix structure, which combines aspects of both the functional and projectized structures.

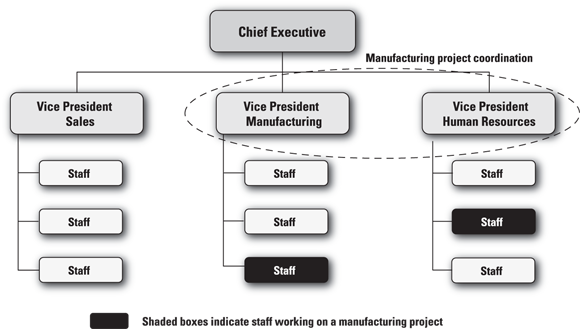

The functional structure

The functional organization structure (see Figure 11-1 for an example) brings together people who perform similar tasks or who use the same kinds of skills and knowledge in functional groups. In this structure, people are managed through clear lines of authority that extend through each group to the head of the group and, ultimately, to a single person at the top. For example, in Figure 11-1, you see that all people who perform human resources functions for the organization (such as recruiting, training, and benefits management) are located in the human resources group, which reports to the chief executive.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 11-1: A functional structure for administering projects.

Depending on the nature of the project and the skills and knowledge required for it, a project in the functional structure may be handled completely by staff within a particular functional group. However, as illustrated in Figure 11-1, if the manufacturing group is performing a project that requires the expertise of a person from the human resources group, the vice president of manufacturing must make a formal agreement with the vice president of human resources to make the necessary human resources staffer available to work on the project. The vice president of human resources must then manage this person as they perform their tasks for the project.

Project managers have less authority over project team members in the functional structure than in any other form of project organization. In fact, they serve more as a project coordinator than a project manager because the functional managers maintain all authority over the project team members and the project budget.

Advantages of the functional structure

Functional groups have the following advantages:

- They are reservoirs of skills and knowledge in their areas of expertise. Group members are hired for their technical credentials and continue to develop their capabilities through their work assignments.

- Their well-established communication processes and decision-making procedures provide timely and consistent support for the group’s projects. From the beginning of their assignments, group members effectively work with and support one another because they know with whom, how, and when to share important task information. Decisions are made promptly because areas of authority are clearly defined.

- They provide people with a focused and supportive job environment. Group members work alongside colleagues who share similar professional interests. Each member has a well-defined career path and one manager who gives them assignments and reviews their performance. The established interpersonal relationships among the group’s members facilitate effective collaborative work efforts.

Disadvantages of the functional structure

- It hampers effective collaboration among different functional groups. Group members’ working relationships are mainly with others in their group, and management assesses their performance on how well they perform in the group’s area of specialization. This setup, often referred to as “operating in silos,” makes effective collaboration with other groups on a project difficult.

- The members’ main interest is to perform the tasks in their group’s specialty area effectively rather than to achieve goals and results that may involve and affect other groups in the organization. Group members’ professional interests and working relationships are mostly with others in their group, and their manager, who gives them their work assignments and evaluates their performance, is the head of the functional group. This environment, whether directly or indirectly, incentivizes members to be most concerned with and to give the highest priority to their functional group’s task assignments.

- One functional group may have difficulty getting buy-in and support for its project from other functional groups that must support or will be affected by the project. Each functional group can initiate a project without consulting other functional groups. As a result, people in these other areas may be reluctant to support such a project when it doesn’t address their needs in the most effective way. They may also be reluctant to support it because the project may be competing with projects from their own functional group for scarce resources.

The projectized structure

The projectized organization structure groups together all personnel working on a particular project. Project team members are often located together and under the direct authority of the project manager for the duration of the project. As an example, you see in Figure 11-2 that a design engineer, an IT specialist, and a test engineer all work on Project A, while a different design engineer and a different test engineer work on Project B.

Project managers have almost total authority over the members of their team in the projectized structure. They make assignments and direct team members’ task efforts; they control the project budget; they conduct team members’ performance assessments and approves team members’ raises and bonuses; and they approve requests for paid time off.

Advantages of the projectized structure

The projectized structure has the following advantages:

- All members of a project team report directly to the project manager. This clarified and simplified reporting structure reduces the potential for conflicting demands on team members’ time and results in fewer and shorter lines of communication. In addition, it facilitates faster project decision-making.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 11-2: A projectized structure for administering projects.

- Project team members can more easily develop a shared sense of identity, resulting in a stronger commitment to one another and to the success of the project. Consistent focus on a single project with the same group of team members gives people a greater appreciation of one another’s strengths and limitations, as well as a deeper understanding of and a stronger belief in the value of the intended project results.

- Everyone on the team shares the processes for performing project work, communication, conflict resolution, and decision-making. The projectized structure enhances project productivity and efficiency because more time can be devoted to doing work rather than to creating systems to support doing the work.

Disadvantages of the projectized structure

- Higher personnel costs: Even when several projects have similar personnel needs, different people with the same skill set have to be assigned to each one. As a result, chances are greater that projects won’t be able to fully support people with specialized skills and knowledge, which can lead to either keeping people on projects longer than they’re actually needed or having to cover people’s salaries when their project doesn’t have enough work to support them full time.

- Reduced technical interchange between projects: Providing all the skills and knowledge required to perform a project by assigning people full time to the project team reduces the need and the opportunity for collaborating and sharing knowledge and experiences with people on other teams.

- Reduced career continuity, opportunities, and sense of job security: Because people are hired to work on one specific project team, they have no guarantee that the organization will need their services when their current project comes to an end.

The matrix structure

With increasing frequency, projects today involve and affect many functional areas within an organization. As a result, personnel from these different areas must work together to successfully accomplish the project work. The matrix organization structure combines elements of both the functional and projectized structures to facilitate the responsive and effective participation of people from different parts of the organization on projects that need their specialized expertise.

As Figure 11-3 illustrates, in a matrix organization structure, people from different areas of the organization are assigned to lead or work on projects. Project managers guide the performance of project activities while people’s direct supervisors (from groups such as engineering, manufacturing, and sales and marketing) perform administrative tasks like formally appraising people’s performance and approving promotions, salary increases, or requests for time off. Because an individual can be on a project for less than 100 percent of their time, they may work on more than one project at a time (we discuss the key players in a matrix structure in more detail in the later section “Recognizing the Key Players in a Matrix Environment”).

A matrix environment is classified as weak, strong, or balanced, depending on the amount of authority the project managers have over their teams. Here’s a little more info about each of these classifications:

- Weak matrix: Project team members receive most of their direction from their functional managers. Project managers have little, if any, direct authority over team members and actually function more like project coordinators than managers.

- Strong matrix: Companies with strong matrix structures choose project managers for new projects from a pool of people whose only job is to manage projects. The companies never ask these people to serve as team members. Often these project managers form a single organizational unit that reports to a manager of project managers. In addition to directing and guiding project work, these project managers have certain administrative authority over the team members, such as the right to participate in their performance appraisals.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 11-3: The general matrix organization structure.

- Balanced matrix: This type of matrix environment is a blend of the weak and strong environments. People are assigned to lead projects or serve as team members based on the projects’ needs rather than on their job descriptions. Although the project manager may have some administrative authority over team members (such as approving requests for time off), for the most part, the project manager guides, coordinates, and facilitates the project.

Check out the later section “Working Successfully in a Matrix Environment” for more information on the matrix structure.

Advantages of the matrix structure

A matrix environment offers many benefits, including the following:

- Teams can assemble rapidly. Because you have a larger resource pool from which to choose your project team, you don’t have to wait for a few people to finish current assignments before they can start on your project. Additionally, this approach reduces the time-consuming process of hiring and ramping up someone new from the outside.

- Specialized expertise can be available for several different projects. Projects often require a small amount of effort from a person with highly specialized knowledge or skills. If your project alone can’t provide sufficient funds to hire this person full time, perhaps several projects together, each using a portion of the expert’s time, can.

- The matrix supports team members’ near-term project work and longer-term career and skills development. Project resources benefit from not one but two advocates in a matrix environment. Project managers advocate for day-to-day project work, while functional managers advocate for the nurturing of existing skill sets as well as the acquisition and sharing of new knowledge among functional team members, with an eye on opportunities for individual career growth.

Disadvantages of the matrix structure

- Team members working on multiple projects respond to two or more managers. Each team member has at least two people giving them direction — a project manager (who coordinates project work and team support) and a functional manager (who coordinates the team member’s project assignments, completes their performance appraisal, and various other administrative duties). When these two managers are at similar levels in the organization, resolving conflicting demands for the team member’s time can be difficult and may even require escalation to leadership.

- Team members’ priorities can be changed away from the project by the functional manager, particularly in a weak matrix structure, if this person overrode the project manager’s authority.

- Team members may not be familiar with one another’s styles and knowledge. Because team members may not have worked extensively together, they may require some time to become comfortable with one another’s work styles and behaviors.

- Team members may focus more on their individual assignments and less on the project and its goals. For example, a quality assurance specialist may be responsible for documenting and executing test cases on a newly developed portion of software code. In such a case, the QA specialist may be less concerned about the project’s target go-live date, which is dependent on the software passing all QA testing, and more concerned about learning and incorporating a new, automated testing tool that their functional manager acquired and plans to eventually require to be used on all software development projects.

Recognizing the Key Players in a Matrix Environment

The matrix structure discussed earlier in this chapter makes it easier for people from diverse parts of the organization to contribute their expertise to different projects. However, working in a matrix environment requires that project managers deal with the styles, interests, and demands of more people who have some degree of control over their project’s resources, goals, and objectives than in a functional or projectized structure.

In a matrix environment, the following people play critical roles in every project’s success:

- Project manager: The person ultimately responsible for the successful completion of the project

- Project team members: People responsible for successfully performing individual project activities

- Functional managers: The team members’ direct-line supervisors

- Project owner: The person who initiates the project, finances it, and heads up the business unit where the project’s products will be used

- Project sponsor: The person who provides top-level project justification, funding, liaison, and reporting, as well as specific and pragmatic support to the project manager

- Upper management: People in charge of the organization’s major business units, also referred to generally as “leadership” or “executive leadership”

The following sections discuss how each of these people can help your project succeed.

The project manager

If you’re the project manager, you’re responsible for all aspects of the project. Being responsible doesn’t mean you have to do the whole project yourself, but you do have to see that every activity is completed satisfactorily (see Chapter 12 for definitions of authority, responsibility, and accountability). In this role, you’re specifically responsible for the following:

- Defining, drafting, and championing the project charter (collaboratively with the project sponsor) and maintaining it throughout the life of the project (see Chapter 3 for more information on the project charter).

- Determining objectives (see Chapter 5), schedules (see Chapter 7), and resource budgets (see Chapters 8 and 9).

- Ensuring you have a clear, feasible project plan to reach your performance targets (see Chapter 6).

- Identifying and managing project risks (see Chapter 10).

- Creating and sustaining a well-organized, focused, and committed team (see Chapters 12 and 13 in addition to this one).

- Selecting or creating your team’s operating practices and procedures (see Chapter 13).

- Monitoring performance against plans and dealing with any problems that arise (see Chapter 14).

- Resolving priority, work approach, or interpersonal conflicts (see Chapter 13).

- Identifying and facilitating the resolution of project issues and problems (see Chapter 14).

- Controlling project changes (see Chapter 14).

- Reporting on project activities (see Chapter 15).

- Keeping your clients informed and committed (see Chapter 15).

- Accomplishing objectives within time and budget targets (see Part 4).

- Contributing to your team members’ performance appraisals (see Chapter 17).

Project team members

Project team members must satisfy the requests of both their functional managers and their project managers. As a team member, your responsibilities related to project assignments include the following:

- Performing tasks in accordance with the highest standards of technical excellence in your field

- Performing assignments on time and within budget

- Maintaining the special skills and knowledge required to do the work well

In addition, you’re responsible for working with and supporting your team members’ project efforts. Such help may entail the following:

- Considering the effect your actions may have on your team members’ tasks

- Identifying situations and problems that may affect team members’ tasks

- Keeping your team members informed of your progress, accomplishments, and any problems you encounter

Functional managers

Functional managers are responsible for orchestrating their staff’s assignments among different projects. In addition, they provide the necessary resources for their staff to perform their work in accordance with the highest standards of technical excellence. Specifically, as a functional manager, you’re responsible for the following:

- Developing or approving plans that specify the type, timing, and amount of resources required to perform tasks in their area of specialty

- Ensuring team members are available to perform their assigned tasks for the promised amount of time

- Providing technical expertise and guidance to help team members solve problems related to their project assignments

- Providing the equipment and facilities needed for a person to do their work

- Helping people maintain their technical skills and knowledge

- Ensuring members of the functional group use consistent methodological approaches on all their projects

- Completing team members’ performance appraisals

- Recognizing performance with salary increases, promotions, and job assignments

- Approving team members’ requests for paid time off, administrative leave, training, and other activities that take time away from the job

The project owner

Project owners initiate the project, finance it, and are in charge of the business unit where the products produced by the project will be used to generate the desired business benefits. They are very important project drivers, one of the stakeholders who will define the business benefits to be realized from the project (flip to Chapter 4 for more information on stakeholders). If you are the project owner, you should expect to perform the following tasks:

- Helping to define the business benefits to be produced by the project (see Chapters 3 and 5 for more establishing the desired project results)

- Helping to ensure the design of the project will produce those desired business benefits

- Assessing the extent to which the benefits desired from the project are in fact realized

- Ensuring all information, people knowledgeable about the different aspects of operations, and required access to facilities and equipment are provided as promised when needed

The project sponsor

Originally, a project sponsor was a person who provided resources to support project activities. However, as projects evolved to become an integral part of an organization’s operations, the responsibilities of the project sponsor (often referred to as the executive sponsor) have expanded to include corporate and top-level project justification, funding, liaison, and reporting, as well as the provision of specific and pragmatic support to the project manager. Following are responsibilities you may have if you are an executive sponsor:

- Fleshing out the needs of the project in the business case (see Chapter 3 for more information)

- Estimating the funds, the schedule, and the resources needed for the project (check out Chapters 7, 8, and 9 for more details)

- Securing the funding and other required resources for the project

- Collaborating with the project manager to create and ultimately approve the project charter (check out Chapter 3 for more on this)

- Ensuring that the project is producing high-quality deliverables

- Supporting the assessment and management of project risks (see Chapter 10)

- Publicizing, promoting, and championing the project, especially to more senior-level audiences

- Helping to establish the internal and external credibility and support necessary for the project manager and the project team

- Providing oversight and executive support, as needed, to facilitate the successful performance of project activities

- Providing senior management with information about project activities performed, resources expended, results produced, and any issues that may adversely affect the chances of a project’s successful completion

- Ensuring the business benefits desired from the project are realized

Upper management

Upper management creates the organizational environment; oversees the development and use of operating policies, procedures, and practices; and encourages and funds the development of required information systems. More specifically, if you’re in upper management, you’re responsible for the following:

- Creating the organizational mission and goals that provide the framework for selecting projects

- Setting policies and procedures for addressing priorities and conflicts

- Creating and maintaining labor and financial information systems

- Providing facilities and equipment to support project work

- Defining the limits of managers’ decision-making authority

- Helping to resolve project issues and decisions that can’t be handled successfully at lower levels in the organization

Working Successfully in a Matrix Environment

Achieving success in a matrix environment requires that you effectively align and coordinate the people who support your project, deflecting any forces that pull those people in different directions. This section can help you, as a project manager, get the highest-quality work from your team members in a matrix environment and timely and effective support from the functional and senior managers.

Creating and continually reinforcing a team identity

- Clarify team vision and working relationships. As soon as you have a team, work with the team members to develop a project mission that members can understand and support. Give people an opportunity to become familiar with each other’s work style.

- Define team procedures. Encourage your team to develop its own work procedures instead of allowing people to use the approaches of their respective functional groups.

- Clearly define each team member’s roles and responsibilities on the project tasks they’ll be performing. You also should include any authority that team members can use in the performance of their assigned tasks.

- Clarify each person’s authority. Team members may have to represent their functional areas when making project decisions. Clarify each team member’s level of independent authority to make such decisions and determine who outside the team can make any decisions that are beyond the purview of the team member.

- Be aware of and attend to your team’s functioning. Help people establish comfortable and productive interpersonal relationships. Continue to support these relationships throughout your project.

- Reinforce the overall project goals and the dependence of team members on one another. As the project manager, you must continually remind team members of the overarching project goals and focus their attention on how they influence and affect each other’s work.

Getting team member commitment

Team members typically have little or no authority over each other in a matrix environment. Therefore, they perform their project assignments because they choose to, not because they have to. Work with people initially and throughout your project to encourage them to commit to your project’s goals (see Chapter 16 for more on how to encourage team member buy-in).

Eliciting support from other people in the environment

- Get a champion. Because you most likely don’t have authority over all the people who affect the chances for your project’s success, get an ally who does have that authority — and do so as soon as possible. This project champion can help resolve team members’ schedule and interpersonal conflicts and raise your project’s visibility in the organization (see Chapter 4 for more information on this role).

- Ask for and acknowledge the support of your team members’ functional managers. By thanking functional managers for supporting their staff and allowing the staff to honor their project commitments, you’re encouraging those managers to provide similar support for you and others in the future.

- Work closely with your project’s executive sponsor. See the section “The project sponsor” earlier in this chapter, which discusses the role and responsibilities of the project executive sponsor.

Heading off common problems before they arise

- Plan in sufficient detail. Work with team members to clearly and concisely define the project work and each person’s specific roles and responsibilities for all activities. This planning helps people more accurately estimate the amount of effort they need to give and the timing of that effort for each assignment.

- Identify and address conflicts promptly. Conflicts frequently arise in a matrix environment, given people’s diverse responsibilities, different styles, and lack of experience working together. Encourage people to identify and discuss conflicts as soon as they occur. Develop systems and procedures to deal with conflicts promptly — before they get out of hand.

- Encourage open communication among team members, especially regarding problems and frustrations. The earlier you hear about problems, the more time you have to deal with them. Discussing and resolving team issues encourages working relationships that are more enjoyable and productive.

- Encourage upper management to establish an oversight committee to monitor project performance and to address resource and other conflicts. Project and functional managers must focus on the goals for their respective areas of responsibility. Often, both groups rely on the same pool of people to reach these goals. But these diverse needs can place conflicting demands on people’s time and effort. An upper-management oversight committee can ensure that the needs of the entire organization are considered when addressing these conflicts.

Relating This Chapter to the PMP Exam and PMBOK 7

Table 11-1 notes topics in this chapter that may be addressed on the Project Management Professional (PMP) certification exam and that are included in A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, 7th Edition (PMBOK 7).

TABLE 11-1 Chapter 11 Topics in Relation to the PMP Exam and PMBOK 7

Topic | Location in This Chapter | Location in PMBOK 7 | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

Functional, projectized, and matrix organizational structures | 2.2.1. Project Team Management and Leadership | This book discusses in more detail than PMBOK 7 the three most common organizational structures for handling projects. | |

Roles of project manager, project team members, functional managers, project owner, project sponsor, and upper management | 2.2.1. Project Team Management and Leadership 2.1. Stakeholder Performance Domain | This book discusses in more detail than PMBOK 7 how each entity can support a project team’s successful performance. |

The functional structure has the following drawbacks:

The functional structure has the following drawbacks:  On occasion, you may hear people use the terms project director and project leader, both of which sound similar to project manager. Check with your organization, but usually manager and director describe a similar position. Project leader, however, is a different story. People often think of management as focusing on issues and tasks and leadership as focusing on people and teams; management also deals with established procedures, while leadership deals with change. Therefore, calling someone a project leader emphasizes their responsibility to focus and energize the people supporting the project, as opposed to the more technical tasks of planning and controlling. But again, check with your organization to be sure the term leader is meant to convey this message (often project leader is just another term for project manager — go figure!).

On occasion, you may hear people use the terms project director and project leader, both of which sound similar to project manager. Check with your organization, but usually manager and director describe a similar position. Project leader, however, is a different story. People often think of management as focusing on issues and tasks and leadership as focusing on people and teams; management also deals with established procedures, while leadership deals with change. Therefore, calling someone a project leader emphasizes their responsibility to focus and energize the people supporting the project, as opposed to the more technical tasks of planning and controlling. But again, check with your organization to be sure the term leader is meant to convey this message (often project leader is just another term for project manager — go figure!). The ideal candidate to be a project’s executive sponsor would be a well-respected C-level executive — for example, a CIO (chief information officer) or CFO (chief financial officer) — in the line of authority above the department that will use the new products created by the project to produce the desired business benefits.

The ideal candidate to be a project’s executive sponsor would be a well-respected C-level executive — for example, a CIO (chief information officer) or CFO (chief financial officer) — in the line of authority above the department that will use the new products created by the project to produce the desired business benefits.