Chapter 8

Establishing Whom You Need, How Much of Their Time, and When

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Focusing first on people’s abilities

Focusing first on people’s abilities

![]() Accurately planning your project’s personnel needs

Accurately planning your project’s personnel needs

![]() Striking a balance among all your resource commitments

Striking a balance among all your resource commitments

Consider the following declaration by a stressed-out project manager: “We’ve done so much with so little for so long [that] they now expect us to do everything with nothing!”

Of course, the truth is you can’t accomplish anything for nothing; everything has a cost. You live in a world of limited resources and not enough time, which means you always have more work to do than the available time and resources will support. However, carefully determining the number and characteristics of the personnel you need to perform your project and when you’ll need them increases your chances of succeeding by enabling you to do the following:

- Ensure the most qualified people available are assigned to each task.

- Explain more effectively to team members what you’re asking them to contribute to the project.

- Develop more-accurate and more-realistic schedules.

- Ensure that people are on hand when they’re needed.

- Monitor resource expenditures to identify and address possible overruns or underruns.

Some organizations have procedures that require you to detail and track every resource on every project. Other organizations don’t formally plan or track project resources at all. However, even if your organization doesn’t require you to plan your resource needs and track your resource use, doing so will be invaluable to your project’s success.

This chapter helps you figure out whom you need on your project, when, and for how long. It also discusses how to identify and manage conflicting demands for people’s time.

Getting the Information You Need to Match People to Tasks

Your project’s success rests on your ability to enlist the help of appropriately qualified people to perform your project’s work. In addition to a person’s availability, their ability to perform a task is determined by the following:

- Skill: Ability to do something well

- Knowledge: Familiarity, awareness, or understanding of facts or principles about a subject

- Interest: Curiosity or concern about something

The level of skills and knowledge you’ll require to perform an activity successfully depends on whether you’ll be working under someone else’s guidance and direction, working independently, or managing others who are applying the skills and knowledge.

As you find out in the following sections, getting appropriately qualified people to perform your project’s activities entails the following steps:

- Determining the skills and knowledge that each activity requires.

- Confirming that the people assigned to those activities possess the required skills and knowledge and that they’re genuinely interested in working on their assignments.

Deciding what skills and knowledge team members must have

To begin deciding the skills and knowledge that people must have for your project, obtain a complete list of all your project’s activities. Specify your project’s activities by decomposing all the work packages in your project’s work breakdown structure (WBS) into the individual actions required to complete them (work packages are the lowest-level components in a WBS).

Next, determine each activity’s skill and knowledge requirements by reviewing activity descriptions and consulting with subject-matter experts, your human resources department, functional department managers, and people who have worked on similar projects and activities in the past.

Because you’ll ask functional managers and others in the organization to assign staff with the appropriate skills and knowledge to your project, you should ask these people before you prepare your list of required skills and knowledge what schemes (if any) they or the organization currently use to describe staff’s skills and knowledge. Then, if possible, you can use the same or a similar scheme to describe your project’s skill and knowledge requirements to make it easier for the managers to identify those people who are appropriately qualified to address your project’s requirements.

If your organization doesn’t have a skills and knowledge registry in one or more areas, you may consider helping to develop one.

A possible format of a skills and knowledge registry that contains all the activities performed in Project A in your organization is presented in Figure 8-1. The left column contains the identifying code of the skill or knowledge required (the figure contains skills labeled S1 for Skill #1 and so on, and knowledge areas labeled K1 for Knowledge area #1 and so on), and the next two columns contain the name and a brief description of each of the skills and knowledge areas listed.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 8-1: Listing skills and knowledge that may be required to perform activities in your organization in a skills and knowledge registry.

Figure 8-2 shows a sample of a skills and knowledge requirements list for a project. A project’s skills and knowledge registry contains a single entry for each skill and knowledge area that’s required to perform one or more activities in the project. However, the project’s skills and knowledge requirements list includes all the skill and knowledge areas that are required to perform each activity in the project. For example, if the skill of questionnaire design is required to perform five different activities in a project, it would be listed five separate times in the project’s skills and knowledge requirements list. However, it would be listed only once in the project’s skills and requirements registry.

![Schematic illustration of Displaying the skills and knowledge required to perform the activities in [Project Name] in a skills and knowledge requirements list.](https://imgdetail.ebookreading.net/2023/10/9781119869818/9781119869818__9781119869818__files__images__9781119869818-fg0802.png)

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 8-2: Displaying the skills and knowledge required to perform the activities in [Project Name] in a skills and knowledge requirements list.

- The required levels of proficiency in the needed skills and knowledge.

- Whether the assignment will entail working under someone else’s guidance when applying the skills or knowledge, working alone to apply the skills or knowledge, or managing others who are applying the skills or knowledge.

An example of a scheme that describes these two aspects of a skill or knowledge requirement is (X, Y). X is the required level of proficiency in the skill or knowledge and can have the following values:

- 1 = requires a basic level of proficiency

- 2 = requires an intermediate level of proficiency

- 3 = requires an advanced level of proficiency

Y is the amount of oversight required when applying the skill or knowledge and has the following values:

- 1 = must work under supervision when applying the skill or knowledge

- 2 = must be able to work independently, with little or no direct supervision, when applying the skill or knowledge

- 3 = must be able to manage others who are applying the skill or knowledge

Further, the more clearly you define a skill or knowledge and the level of proficiency in that skill or knowledge required to perform a task, the better able you are to obtain a person who is qualified to perform the job.

Therefore, if you express proficiency as being basic, intermediate, or advanced, you must define clearly what each term means. As an example, for the skill of typing, you may decide that typing 30 words per minute or less with no errors is a basic level of proficiency, typing between 30 and 80 is an intermediate level, and typing more than 80 words per minute is an advanced level. Whatever your specific criteria are for deciding whether a person’s proficiency in a skill or knowledge is basic, intermediate, or advanced, be sure to document them and make them available to all people involved in selecting people for your project team.

- Training: The organization can develop or make available training in areas in which it has shortages.

- Career development: The organization can encourage individuals to develop skills and knowledge that are in short supply to increase their opportunities for assuming greater responsibilities in the organization.

- Recruiting: Recruiters can look to hire people who have the capabilities that will qualify them for specific job needs in the organization.

- Proposal writing and new business development: Proposals can include information about people’s skills and knowledge to demonstrate the organization’s capability to perform particular types of work.

Representing team members’ skills, knowledge, and interests in a skills matrix

Whether you’re able to influence who’s assigned to your project team, people are assigned to your team without your input, or you assume the role of project manager of an existing team, you need to confirm the skills, knowledge, and interest of your team members.

If you have a team that was assembled without considering your opinion on the capabilities needed to perform your project’s work, you must find out team members’ skills, knowledge, and interests so you can make the most appropriate task assignments. If some or all of your team has been chosen in response to the specific skills and knowledge needs that you discussed with the organization’s management, you should document people’s skills and knowledge and verify their interests, in case you need to assign people to unanticipated tasks that crop up or you have to replace a team member unexpectedly.

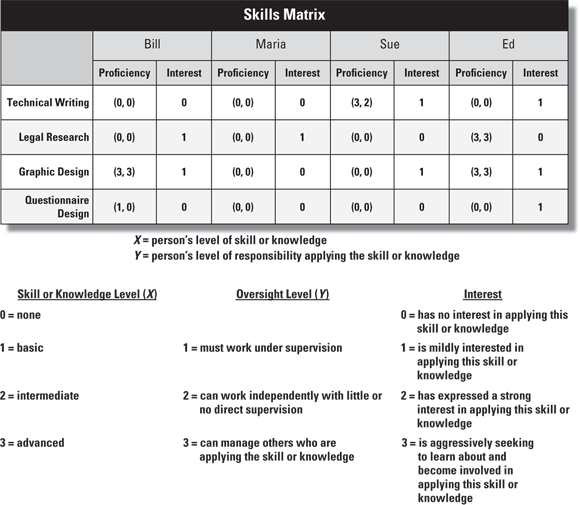

A skills matrix is a table that displays people’s proficiency in specified skills and knowledge, as well as their interest in working on assignments that require these skills and knowledge. Figure 8-3 presents an example of a portion of a skills matrix. The left column identifies skill and knowledge areas, and the top row lists people’s names. At the intersection of the rows and columns, you identify the level of each person’s particular skills, knowledge, and interests.

Figure 8-3 shows that Sue has an advanced level of proficiency in technical writing and can work independently with little or no supervision. In addition, she’s interested in working on technical writing assignments. Ed has an advanced level of proficiency in the area of legal research and is capable of managing others engaged in legal research. However, he’d prefer not to work on legal research tasks. Instead, he wants to work on questionnaire design activities, but he currently has no skills or knowledge in this area.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 8-3: Displaying people’s skills, knowledge, and interests in a skills matrix.

By the way, you may assume that you’d never assign Ed to work on a questionnaire design activity because he has no relevant skills or knowledge. However, if you’re trying to find more people who can develop questionnaires, Ed is a prime candidate. Because he wants to work on these types of assignments, he’s most likely willing to put in extra effort to acquire the skills needed to do so.

Take the following steps to prepare a skills matrix for your team:

Discuss with each team member their skills, knowledge, and interests related to the activities that your project entails.

Explain that you seek this information so you can assign people to the tasks that they’re most interested in and qualified to perform.

Determine each person’s level of interest in working on the tasks for which they have been proposed.

At a minimum, ask people whether they’re interested in the tasks for which they’ve been proposed. If a person isn’t interested in a task, try to find out why and whether you can do anything to modify the assignment to make it more interesting to them.

If a person isn’t interested in a task, you can either not ask and not know the person isn’t interested or ask and (if you get an honest response) know that they aren’t interested. Knowing that a person isn’t interested is better than not knowing, because you can consider the possibility of rearranging assignments or modifying the assignment to address those aspects of it that the person doesn’t find appealing.

If a person isn’t interested in a task, you can either not ask and not know the person isn’t interested or ask and (if you get an honest response) know that they aren’t interested. Knowing that a person isn’t interested is better than not knowing, because you can consider the possibility of rearranging assignments or modifying the assignment to address those aspects of it that the person doesn’t find appealing.Consult with team members’ functional managers and/or the people who assigned them to your project to determine their opinions of the levels of each team member’s skills, knowledge, and interests.

You want to understand why these managers assigned the people they did to your project.

Check to see whether any areas of your organization have already prepared skills matrices.

Find out whether they reflect any information about the extent to which team members have skills and knowledge that you feel are required for your project’s activities.

Incorporate all the information you gather in a skills matrix and review with each team member the portion of the matrix that contains their information.

This review gives you the opportunity to verify that you correctly recorded the information you found and gives the team member a chance to comment on or add to any of the information.

Estimating Needed Commitment

Just having the right skills and knowledge to do a task doesn’t guarantee that a person will successfully complete it. The person must also have sufficient time to perform the necessary work. This section tells you how to prepare a human resources matrix to display the amount of effort people will have to put in to complete their tasks. In addition, this section explains how you can take into account productivity, efficiency, and availability to make your work-effort estimates more accurate.

Using a human resources matrix

Planning your personnel needs begins with identifying whom you need and how much effort they have to invest. You can use a human resources matrix to display this information (see Figure 8-4 for an example of this matrix). The human resources matrix depicts the people assigned to each project activity and the work effort each person will contribute to each assignment.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 8-4: Displaying personnel needs in a human resources matrix.

Work effort or person effort is the actual time a person spends doing an activity. One person-hour of work effort is equal to the amount of work done by one person working full time for one hour. You can express work effort in units of person-hours, workdays, man-weeks (technically accurate, although not inclusive), and so forth.

Work effort is related to, but different from, duration. Work effort is a measure of resource use; duration is a measure of time passage (see Chapter 7 for more discussion of duration). Consider the work effort to complete the questionnaire design work package in the human resources matrix in Figure 8-4. According to the matrix, J. Jones works on this activity for 32 person-hours, and an unnamed analyst works on it for 24 person-hours.

Knowing the work effort required to complete a work package alone, however, doesn’t tell you the duration of the work package. For example, if both people assigned to the questionnaire design work package in Figure 8-4 can do their work on it at the same time, if they’re both assigned 100 percent to the project, and if no other aspects of the task take additional time, the activity may be finished in four days. Assuming one workday is equal to eight person-hours, J. Jones requires at least four days to complete his 32 person-hours of work, and the analyst requires at least three days to complete their 24 person-hours of work. Because they’re working concurrently, the fastest they can both be done is in four days. However, if either person is available for less than 100 percent of the time, if one or both people must work overtime, or if one person has to finish their work before the other can start, the duration will be greater than four days.

Identifying needed personnel in a human resources matrix

Begin to create your human resources matrix by specifying in the top row the different types of personnel you need for your project. You can use three types of information to identify the people you need to have on your project team:

- Skills and knowledge: The specific skills and knowledge that the person who’ll do the work must have

- Position name or title: The job title or position name of the person who’ll do the work

- Name: The name of the person who’ll do the work

Eventually, you want to specify all three pieces of information for each project team member. Early in your planning, try to specify needed skills and knowledge, such as must be able to develop work-process flowcharts or must be able to use Microsoft PowerPoint. If you can identify the exact skills and knowledge that a person must have for a particular task, you increase the chances that the proper person will be assigned.

Estimating required work effort

For all work packages, estimate the work effort that each person has to invest and enter the numbers in the appropriate boxes in the human resources matrix (refer to Figure 8-4). As you develop your work-effort estimates, do the following:

- Describe in detail all work related to performing the activity. Include work directly and indirectly related:

- Examples of work directly related to an activity include writing a report, meeting with clients, performing a laboratory test, and designing a new logo.

- Examples of indirectly related work include receiving training to perform activity-related work and preparing periodic activity-progress reports.

Consider history. Past history doesn’t guarantee future performance, but it does provide a guideline for what’s possible. Determine whether a work package has been done before. If it has, review written records to determine the work effort spent on it. If written records weren’t kept, ask people who’ve done the activity before to estimate the work effort they invested.

When using prior history to support your estimates, make sure:

When using prior history to support your estimates, make sure: - The people who performed the work had qualifications and experience similar to those of the people who’ll work on your project.

- The facilities, equipment, and technology used were similar to those that’ll be used for your project.

- The timeframe was similar to the one you anticipate for your project.

Have the person who’ll actually do the work participate in estimating the amount of work effort that will be required. Having people contribute to their work-effort estimates provides the following benefits:

- Their understanding of the activity improves.

- The estimates are based on their particular skills, knowledge, and prior experience, which makes them more accurate.

- Their commitment to do the work for that level of work effort increases.

If you know who’ll be working on the activity, have those people participate during the initial planning. If people don’t join the project team until the start of or during the project, have them review and comment on the plans you’ve developed. Then update your plans as needed.

If you know who’ll be working on the activity, have those people participate during the initial planning. If people don’t join the project team until the start of or during the project, have them review and comment on the plans you’ve developed. Then update your plans as needed.- Consult with experts familiar with the type of work you need done on your project, even if they haven’t performed work exactly like it before. Incorporating experience and knowledge from different sources improves the accuracy of your estimate.

Factoring productivity, efficiency, and availability into work-effort estimates

Being assigned to a project full time doesn’t mean a person can perform project work at peak productivity 40 hours per week, 52 weeks per year. Additional personal and organizational activities reduce the amount of work people produce. Therefore, consider each of the following factors when you estimate the number of hours that people need to complete their project assignments:

- Productivity: The results a person produces per unit of time that they spend on an activity. The following factors affect a person’s productivity:

- Knowledge and skills: The raw talent and capability a person has to perform a particular task

- Prior experience: A person’s familiarity with the work and the typical problems of a particular task

- Sense of urgency: A person’s drive to generate the desired results within established timeframes (urgency influences a person’s focus and concentration on an activity)

- Ability to switch among several tasks: A person’s level of comfort moving to a second task when they hit a roadblock in their first one so that they don’t sit around stewing about their frustrations and wasting time

- The quality and setup of the physical environment: Proximity and arrangement of a person’s furniture and the support equipment they use; also the availability and condition of the equipment and resources

Efficiency: The proportion of time a person spends on project work as opposed to organizational tasks that aren’t related to specific projects. The following factors affect a person’s efficiency:

- Non-project-specific professional activities: The time a person spends attending general organization meetings, handling incidental requests, and reading technical journals and periodicals about their field of specialty

- Personal activities: The time a person spends getting a drink of water, going to the restroom, organizing their work area, conducting personal business on the job, and talking about non-work-related topics with co-workers

The more time a person spends each day on non-project-specific and personal activities, the less time they have to work on their project assignments. Check out the nearby sidebar “The truth is out: How workers really spend their time” for more info. We also discuss efficiency in the upcoming two sections.

- Availability: The portion of time a person is at the job as opposed to on leave. Organizational policies regarding employee vacation days, sick days, holidays, personal days, mental health days, administrative leave, and so on define a person’s availability.

Reflecting efficiency when you use historical data

How you reflect efficiency in your estimates depends on whether and how you track work effort. If you base your work-effort estimates on historical data from time sheets and if either of the following situations is true, you don’t have to factor in a separate measure for efficiency:

- Your time sheets have one or more categories to show time spent on non-project-specific work, and people accurately report the actual time they spend on their different activities. In this case, the historical data represent the actual number of hours people worked on the activity in the past. Thus, you can comfortably use the numbers from your time sheets to estimate the actual level of effort this activity will require in the future, as long as people continue to record in separate categories the hours they spend on non-project-specific activities.

Your time sheets have no category for recording time spent on non-project-specific work. However, you report accurately (by activity) the time you spend on work-related activities, and you apportion in a consistent manner your non-project-specific work among the available project activities. In this case, the historical data reflect the number of hours that people recorded they spent on the activity in the past, which includes time they actually spent on the activity and a portion of the total time they spent on non-project-specific work.

Again, if people’s time-recording practices haven’t changed, you can use these numbers to estimate the hours that people will record doing this same activity in the future.

- People aren’t allowed to record overtime, so some hours actually spent on an activity may never be known.

- People fill out their time sheets for a period several days before the period is over, so they must guess what their hourly allocations for the next several days will be.

- People copy the work-effort estimates from the project plan onto their time sheets each period instead of recording the actual number of hours they spend.

If any of these situations exists in your organization, don’t use historical data from time sheets to support your work-effort estimates for your current project. Instead, use one or more of the other approaches discussed in the earlier section “Estimating required work effort.”

Accounting for efficiency in personal work-effort estimates

If you base work-effort estimates on the opinions of people who’ll do the activities or who have done similar activities in the past rather than on historical records, you have to factor in a measure of efficiency.

First, ask the person from whom you’re getting your information to estimate the required work effort assuming they could work at 100 percent efficiency (in other words, ask them not to worry about normal interruptions during the day, having to work on multiple tasks at a time, and so on). Then modify the estimate to reflect efficiency by doing the following:

- If the person will use a time sheet that has one or more categories for non-project-specific work, use their original work-effort estimate

- If the person will use a time sheet that doesn’t have categories to record non-project-specific work, add an additional amount to their original estimate to account for their efficiency

As an example, suppose a person estimates that they need 30 person-hours to perform a task (if they can be 100 percent efficient) and their time sheets have no categories for recording non-project-specific work. If you estimate that they’ll work at about 75 percent efficiency, allow them to charge 40 person-hours to your project to complete the task (75 percent of 40 person-hours is 30 person-hours — the amount you really need).

Failure to consider efficiency when estimating and reviewing project work effort can lead to incorrect conclusions about people’s performance. Suppose your manager assigns you a project on Monday morning. They tell you the project will take about 40 person-hours, but they really need it by Friday close of business. You work intensely all week and finish the task by Friday close of business. In the process, you record 55 hours for the project on your time sheet.

If your manager doesn’t realize that their initial estimate of 40 person-hours was based on your working at 100 percent efficiency, they’ll think you took 15 hours longer than you should have. On the other hand, if your manager recognizes that 55 person-hours on the job translates into about 40 person-hours of work on specific project tasks, they will appreciate that you invested extra effort to meet the aggressive deadline.

The longer you’re involved in an assignment, the more important efficiency and availability become. Suppose you decide you have to spend one hour on an assignment. You can reasonably figure your availability is 100 percent and your efficiency is 100 percent, so you charge one hour for the assignment. If you need to spend six hours on an assignment, you can figure your availability is 100 percent, but you must consider 75 percent efficiency (or a similar planning figure). Therefore, charge one workday (eight work hours) to ensure that you can spend the six hours on your assignment.

However, if you plan to devote one month or more to your assignment, you’ll most likely take some leave days during that time. Even though your project budget doesn’t have to pay for your annual or sick leave, one person-month means you have about 97 hours for productive work on your assignment, assuming 75 percent efficiency and 75 percent availability (2,080 hours total in a year divided by 12 months in a year multiplied by 0.75 efficiency multiplied by 0.75 availability).

The numbers in Table 8-1 depict productive person-hours available at different levels of efficiency and availability. If your organization uses different levels of efficiency or availability, develop your own planning figures.

- Clearly define your work packages. Minimize the use of technical jargon and describe associated work processes (see Chapter 6 for more details).

- Subdivide your work. Do so until you estimate that your lowest-level activities will take two person-weeks or less.

- Review project personnel and task assignments regularly and update the related work-effort estimates when changes occur.

TABLE 8-1 Person-Hours Available for Project Work

Productive Person-Hours Available | |||

|---|---|---|---|

100 Percent Efficiency, 100 Percent Availability | 75 Percent Efficiency, 100 Percent Availability | 75 Percent Efficiency, 75 Percent Availability | |

1 person-day | 8 | 6 | 4.5 |

1 person-week | 40 | 30 | 22.5 |

1 person-month | 173 | 130 | 98 |

1 person-year | 2,080 | 1,560 | 1,170 |

Ensuring Your Project Team Members Can Meet Their Resource Commitments

If you work on only one activity at a time, determining whether you’re overcommitted can be straightforward. But suppose you plan to work on several activities that partially overlap during a particular time period. Then you must decide when to work on each activity to see whether your multitasking has left you overcommitted.

This section shows you how to schedule your work effort for a task, how to identify resource overloads, and how to resolve those overloads.

Planning your initial allocations

The first step in making sure you can handle all your project commitments is to decide when you’ll work on each activity. If your initial plan has you working on more than one activity at the same time, your next task is to determine the total level of effort you’ll need to devote each time period to meet your multiple commitments.

Begin planning out your workload by developing:

- A human resources matrix (see the earlier section “Using a human resources matrix” for more info).

- A person-loading graph or chart for each individual in the human resources matrix.

A person-loading graph (also called a resource histogram) is a bar graph that depicts the level of work effort you’ll spend each day, week, or month on an activity. A person-loading chart presents the same information in a table. The graphical format highlights peaks, valleys, and overloads more effectively, while the tabular format presents exact work-effort amounts more clearly. Prepare a person-loading chart or graph for each project team member.

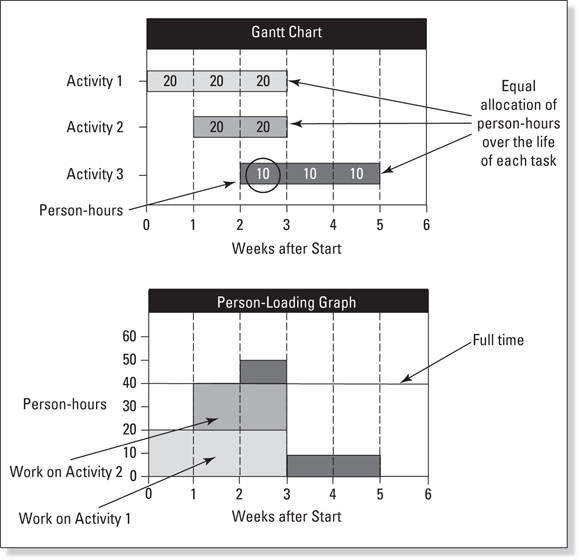

Suppose you plan to work on Activities 1, 2, and 3 of a project. Table 8-2 shows that Activity 1 is scheduled to take three weeks, Activity 2 two weeks, and Activity 3 three weeks. Table 8-2 also shows that you estimate you’ll spend 60 person-hours on Activity 1 (50 percent of your available time over the task’s three-week period), 40 person-hours on Activity 2 (50 percent of your available time over the task’s two-week period), and 30 person-hours on Activity 3 (25 percent of your available time over the task’s three-week period). Consider that you’ve already accounted for efficiency in these estimates; see the earlier section “Estimating Needed Commitment” for more on efficiency. If you don’t have to work on more than one activity at a time, you should have no problem completing each of your three assignments.

The Gantt chart in Figure 8-5 illustrates your initial schedule for completing these three activities (check out Chapter 7 for more on Gantt charts). However, instead of having you work on these activities one at a time, this initial schedule has you working on both Activities 1 and 2 in week 2 and on all three activities in week 3. You have to decide how much effort you’ll put in each week on each of the three tasks to see whether you can work on all three activities as they’re currently scheduled.

As a starting point, assume you’ll spend your time evenly over the life of each activity. That means you’ll work 20 hours a week on Activity 1 during weeks 1, 2, and 3; 20 hours a week on Activity 2 during weeks 2 and 3; and ten hours a week on Activity 3 during weeks 3, 4, and 5, as depicted in the Gantt chart in Figure 8-5.

Determine the total effort you’ll have to devote to the overall project each week by adding up the person-hours you’ll spend on each task each week as follows:

- In week 1, you’ll work 20 person-hours on Activity 1 for a total commitment to the project of 20 person-hours.

- In week 2, you’ll work 20 person-hours on Activity 1 and 20 person-hours on Activity 2 for a total commitment to the project of 40 person-hours.

- In week 3, you’ll work 20 person-hours on Activity 1, 20 person-hours on Activity 2, and ten person-hours on Activity 3 for a total commitment to the project of 50 person-hours.

- In weeks 4 and 5, you’ll work ten person-hours on Activity 3 for a total commitment to the project each week of ten person-hours.

TABLE 8-2 Planned Duration and Work Effort for Three Activities

Activity | Duration (In Weeks) | Work Effort (In Person-Hours) |

|---|---|---|

Activity 1 | 3 | 60 |

Activity 2 | 2 | 40 |

Activity 3 | 3 | 30 |

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 8-5: Planning to work on several activities during the same time period.

The person-loading graph in Figure 8-5 shows these commitments. A quick review reveals that this plan has you working ten hours of overtime in week 3. If you’re comfortable putting in this overtime, this plan works. If you aren’t, you have to come up with an alternative strategy to reduce your week 3 commitments (see the next section for how to do this).

Resolving potential resource overloads

If you don’t change your time allocations for Activity 1, 2, and/or 3 and you’re willing to work only a total of 40 person-hours in week 3, you’ll wind up spending less than the number of hours you planned to on one or more of the activities. Therefore, consider one or more of the following strategies to eliminate your overcommitment:

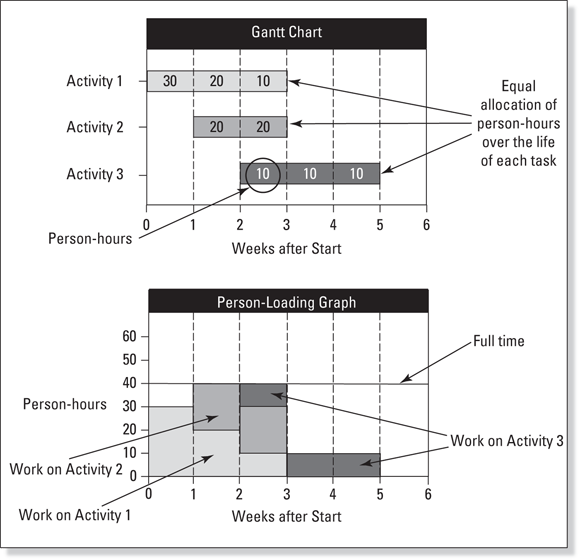

Allocate your time unevenly over the duration of one or more activities. Instead of spending the same number of hours on an activity each week, plan to spend more hours some weeks than others.

Suppose you choose to spend your hours unevenly over the duration of Activity 1 by increasing your commitment by ten hours in the first week and reducing it by ten hours in the third week, as depicted in the Gantt chart in Figure 8-6. The person-loading graph in Figure 8-6 illustrates how this uneven distribution removes your overcommitment in week 3.

Take advantage of any slack time that may exist in your assigned activities. Slack time is the maximum time you can delay an activity without delaying the earliest date by which you can finish the complete project.

Figure 8-7 illustrates that if Activity 3 has at least one week of slack time remaining after its currently planned end date, you can move its start and end dates back by one week and reduce the number of person-hours you’ll be scheduled to work on Activities 1, 2, and 3 during week 3 from 50 to 40, thereby eliminating your overload. Although doing this means that it will take six weeks to complete Activities 1, 2, and 3 instead of five, the fact that the one week you delayed Activity 3 was slack time means the total time to complete the project remains unchanged. (See Chapter 7 for a detailed discussion of slack time.)

- Assign some of the work you were planning to do in week 3 to someone else currently on your project, to a newly assigned team member, or to an external vendor or contractor. Reassigning ten person-hours of your work in week 3 removes your overcommitment.

Show the total hours that each person will spend on your project in a summary person-loading chart, which displays the total number of person-hours each team member is scheduled to spend on the project each week (see Figure 8-8). This chart allows you to do the following:

- Identify who may be available to share the load of overcommitted people.

- Determine the personnel budget for your project by multiplying the number of person-hours people work on the project by their weighted labor rates (see Chapter 9 for more information on setting labor rates).

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 8-6: Eliminating a resource overload by changing the allocation of hours over the activity’s life.

Coordinating assignments across multiple projects

Working on overlapping tasks can place conflicting demands on a person, whether the tasks are on one project or several. Although successfully addressing these conflicts can be more difficult when more than one project manager is involved, the techniques for analyzing them are the same whether you’re the only project manager involved or you’re just one of many. This section illustrates how you can use the techniques and displays from the previous sections to resolve resource conflicts that arise from working on two or more projects at the same time.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 8-7: Eliminating a resource overload by changing the start and end dates of an activity with slack time.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 8-8: Showing total person-hours for a project in a summary person-loading chart.

In general, people on any of your project teams may also be assigned to other projects you’re managing or to other project managers’ projects. If summary person-loading charts are available for each project to which your people are assigned, you can manage each person’s overall resource commitments by combining the information from the projects’ summary person-loading charts into an overall summary person-loading chart.

Figure 8-9 illustrates an overall summary person-loading chart that shows the commitments for each person on one or more of your project teams. This overall summary person-loading chart (titled All Projects) is derived from the summary person-loading charts for each of your team members’ projects.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 8-9: Using person-loading charts to plan your time on several projects.

Figure 8-9 indicates that you’re currently scheduled to work on Projects A, B, and C in February for 40, 20, and 40 person-hours, respectively. Someone requests that you be assigned to work on Project D for 80 person-hours in February.

If you assume that you have a total of 160 person-hours available in February, you can devote 60 person-hours to Project D with no problem, because only 100 person-hours are currently committed. However, you don’t currently have available in February the other 20 person-hours the person is requesting. Therefore, you can consider doing one of the following:

- Find someone to assume 20 person-hours of your commitments to Projects A, B, or C in February.

- Shift your work on one or more of these projects from February to January or March.

- Work overtime.

Relating This Chapter to the PMP Exam and PMBOK 7

Table 8-3 notes topics in this chapter that may be addressed on the Project Management Professional (PMP) certification exam and that are also included in A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, 7th Edition (PMBOK 7).

TABLE 8-3 Chapter 8 Topics in Relation to the PMP Exam and PMBOK 7

Topic | Location in This Chapter | Location in PMBOK 7 | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

Specifying the competencies required to perform the different project activities | 2.4.1. Internal Environment 4.6.3. Plans 4.6.6. Visual Data and Information | Both books emphasize the need to specify the competencies required to perform the project’s activities. This book discusses how to determine the needed competencies. PMBOK 7 uses the term resource management plan whereas this book uses the term human resource management plan; the two are interchangeable. | |

Maintaining a record of team members’ skills, knowledge, and interests | “Representing team members’ skills, knowledge, and interests in a skills matrix” | 4.6.3. Plans | Both books note the need to obtain information about the skills and knowledge of people who may be assigned to your project team. This book discusses the details and provides an example of a skills matrix. |

Specifying and making available the appropriate type and amount of human resources | 4.6.3. Plans 2.2.1. Project Team Management and Leadership | Both books address the importance of having qualified personnel resources assigned to your project team. This book explains how a human resources matrix can be used to record the required characteristics and amounts of needed personnel. | |

Estimating required work effort | 2.4.2.2. Estimating | Both books specify several of the same techniques for estimating the amount of needed personnel and displaying when they’re required. This book discusses how to reflect productivity, efficiency, and availability in the estimates. | |

Handling multiple resource commitments | “Ensuring Your Project Team Members Can Meet Their Resource Commitments” | 2.4.2.2. Estimating 3.6. Demonstrate Leadership Behaviors | Both books emphasize the importance of handling conflicting demands for the same resources. This book discusses and presents examples of specific tools and strategies for addressing and resolving these conflicting demands. |

Often, you want to identify people you want on your project by name. The reason is simple: If you’ve worked with someone before and they did a good job, you want to work with them again. This method is great for that person’s ego, but unfortunately, it often reduces the chances that you’ll get an appropriately qualified person to work on your project. People who develop reputations for excellence often get more requests to participate on projects than they can handle. When you don’t specify the skills and knowledge needed to perform the particular work on your project, the manager — who has to find a substitute for that overextended person — has to infer or assume what skills and knowledge the alternate needs to have.

Often, you want to identify people you want on your project by name. The reason is simple: If you’ve worked with someone before and they did a good job, you want to work with them again. This method is great for that person’s ego, but unfortunately, it often reduces the chances that you’ll get an appropriately qualified person to work on your project. People who develop reputations for excellence often get more requests to participate on projects than they can handle. When you don’t specify the skills and knowledge needed to perform the particular work on your project, the manager — who has to find a substitute for that overextended person — has to infer or assume what skills and knowledge the alternate needs to have.