Chapter 9

Planning for Other Resources and Developing the Budget

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Accounting for your project’s non-personnel resources

Accounting for your project’s non-personnel resources

![]() Preparing a detailed budget for your project

Preparing a detailed budget for your project

A key part of effective project management is ensuring that non-personnel resources are available throughout the project when and where they’re needed and according to specifications. When people are available for a scheduled task but the necessary computers and lab equipment aren’t, your project can have costly delays and unanticipated expenditures. Also, your team members may experience frustration that leads to reduced commitment.

In addition to clearly defined objectives, a workable schedule, and adequate resources, a successful project needs sufficient funds to support the required resources. All major project decisions (including whether to undertake it, whether to continue it, and — after it’s done — whether it was successful) must consider the project’s costs.

This chapter looks at how you can determine, specify, and display your non-personnel resource needs and then how to develop your project budget.

Determining Non-Personnel Resource Needs

In addition to personnel, your project may require a variety of other important resources (such as furniture, fixtures, equipment, raw materials, and information). Plan for these non-personnel resources the same way you plan to meet your personnel requirements (check out Chapter 8 for more on meeting your personnel needs). As part of your plan, develop the following:

- A non-personnel resources matrix

- Non-personnel usage charts

- A non-personnel summary usage chart

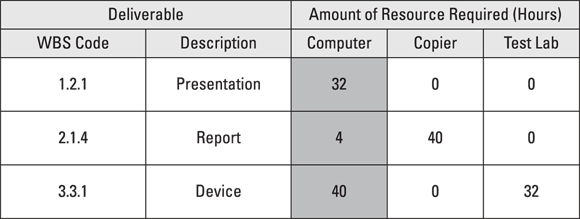

- The non-personnel resources needed to perform the activities that comprise the work package. For example, Figure 9-1 shows that you need computers, copiers, and use of a test laboratory to complete the three listed work packages.

- The required amount of each resource. For example, Figure 9-1 suggests that you need 40 hours of computer time and 32 hours of the test laboratory to create a device. The shaded computer usage numbers in Figure 9-1 are detailed by week in Figure 9-2 later in this chapter.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 9-1: An illustration of a non-personnel resources matrix.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 9-2: An example of a non-personnel usage chart for computer use.

To estimate the amount of each resource you need, examine the nature of the task and the capacity of the resource. For example, determine the amount of copier time you need to reproduce a report by doing the following:

- Estimate the number of report copies.

- Estimate the number of pages per copy.

- Specify the copier capacity in pages per unit of time.

- Multiply the first two numbers and divide the result by the third number to determine the amount of copier time needed to reproduce your reports.

Ensuring that non-personnel resources are available when needed requires that you specify the times that you plan to use them. You can display this information in separate usage charts for each resource. Figure 9-2 illustrates a computer usage chart that depicts the amount of computer time each task requires during each week of your project. For example, the chart indicates that Task 1.2.1 requires six hours of computer time in week 1, four hours in week 2, six hours in week 3, and eight hours in each of weeks 4 and 5. You’d prepare similar charts for required copier time and use of the test lab.

Finally, you display the total amount of each non-personnel resource you require during each week of your project in a non-personnel summary usage chart, as illustrated in Figure 9-3. The information in this chart is taken from the weekly totals in the individual usage charts for each non-personnel resource.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 9-3: An example of a non-personnel summary usage chart.

Making Sense of the Dollars: Project Costs and Budgets

In a world of limited funds, you’re constantly deciding how to get the most return for your investment. Therefore, estimating a project’s costs is important for several reasons:

- It enables you to weigh anticipated benefits against anticipated costs to see whether the project makes sense.

- It allows you to see whether the necessary funds are available to support the project.

- It serves as a guideline to help ensure that you maintain sufficient funds to complete the project.

Although you may not develop and monitor detailed budgets for all your projects, knowing how to work with project costs can make you a better project manager and increase your chances of project success. This section looks at different types of project costs that you may encounter. It then offers helpful tips for developing your own project budget.

Looking at different types of project costs

A project budget is a detailed, time-phased estimate of all resource costs for your project. You typically develop a budget in stages — from an initial rough estimate to a detailed estimate to a completed, approved project budget. On occasion, you may even revise your approved budget while your project is in progress (check out the later section “Refining your budget as your project progresses” for more info).

Your project’s budget includes both direct and indirect costs. Direct costs are costs for resources solely used for your project. Direct costs include the following:

- Salaries for team members on your project.

- Specific materials, supplies, and equipment for your project.

- Travel to perform work on your project.

- Subcontracts that provide support exclusively to your project.

Indirect costs are costs for resources that support more than one project but aren’t readily identifiable with or chargeable to any of the projects individually. Indirect costs fall into the following two categories:

Overhead costs: Costs for products and services for your project that are difficult to subdivide and allocate directly. Examples include employee benefits, office space rent and utilities, general supplies, and the costs of furniture, fixtures, and equipment.

You need an office to work on your project activities, and office space costs money. However, your organization has an annual lease for office space, the space has many individual offices and work areas, and people work on numerous projects throughout the year. Because you have no clear records that specify the dollar amount of the total rent that’s just for the time you spend in your office working on just this project’s activities, your office space is treated as an indirect project cost.

- General and administrative costs: Expenditures that keep your organization operational (if your organization doesn’t exist, you can’t perform your project). Examples include salaries of your sales department, contracts department, finance department, and top management as well as fees for general accounting and legal services.

Suppose you’re planning to design, develop, and produce a company brochure. Direct costs for this project may include the following:

- Labor: Salaries for you and other team members for the hours you work on the brochure

- Materials: The special paper stock for the brochure

- Travel: The costs for driving to investigate firms that may design your brochure cover

- Subcontract: The services of an outside company to design the cover art

Indirect costs for this project may include the following:

- Employee benefits: Benefits (such as annual, sick, and holiday leave; health and life insurance; and retirement plan contributions) for the hours you and the other team members work on the brochure

- Rent: The cost of the office space you use when you’re developing the copy for the brochure

- Equipment: The computer you use to compose the copy for the brochure

- Management and administrative salaries: A portion of the salaries of upper managers and staff who perform the administrative duties necessary to keep your organization functioning

Recognizing the three stages of a project budget

Organization decision-makers would love to have a detailed and accurate budget on hand whenever someone proposed a project so they could assess its relative benefits to the organization and decide whether they have sufficient funds to support it. Unfortunately, you can’t prepare such an estimate until you develop a clear understanding of the work and resources the project will require.

In reality, decisions of whether to go forward with a project and how to undertake it must be made before people can prepare highly accurate budgets. You can develop and refine your project budget in the following stages to provide the best information possible to support important project decisions:

Rough order-of-magnitude estimate: This stage is an initial estimate of costs based on a general sense of the project work. You make this estimate without detailed data. Depending on the nature of the project, the final budget may wind up 100 percent (or more!) higher than this initial estimate.

Prepare a rough order-of-magnitude estimate by considering the costs of similar projects (or similar activities that will be part of your project) that have already been done, applicable cost and productivity ratios (such as the number of assemblies that can be produced per hour), and other methods of approximation.

This estimate sometimes expresses what someone wants to spend rather than what the project will really cost. You typically don’t detail this estimate by lowest-level project activity because you prepare it in a short amount of time before you’ve identified the project activities.

Another often used term for a rough order-of-magnitude (or ROM) estimate is a t-shirt size estimate. At some point, you will be asked to provide t-shirt size estimates for activities, phases, or even projects — keep this as simple as Small, Medium, and Large to satisfy the purpose of this type of estimate. This is a directional, high-level understanding of the general level of effort required to deliver the requested scope.

Another often used term for a rough order-of-magnitude (or ROM) estimate is a t-shirt size estimate. At some point, you will be asked to provide t-shirt size estimates for activities, phases, or even projects — keep this as simple as Small, Medium, and Large to satisfy the purpose of this type of estimate. This is a directional, high-level understanding of the general level of effort required to deliver the requested scope. Whether or not people acknowledge it, initial budget estimates in annual plans and long-range plans are typically rough order-of-magnitude estimates. As such, these estimates may change significantly as the planners define the project in greater detail.

Whether or not people acknowledge it, initial budget estimates in annual plans and long-range plans are typically rough order-of-magnitude estimates. As such, these estimates may change significantly as the planners define the project in greater detail.- Detailed budget estimate: This stage entails an itemization of the estimated costs for each project activity. You prepare this estimate by developing a detailed WBS (see Chapter 6) and estimating the costs of all lowest-level work packages (turn to Chapter 8 for information on estimating work effort, and see the earlier section “Determining Non-Personnel Resource Needs” for ways to estimate your needs for non-personnel resources).

- Completed, approved project budget: This final stage is a detailed project budget that essential people approve and agree to support.

Refining your budget as your project progresses

A project moves through its life cycle as it evolves from an idea to a reality, generally: starting the project, organizing and preparing, carrying out the work, and closing the project (see Chapter 1 for more discussion of the project life cycle). Prepare and refine your budget as your project progresses by following these steps:

Prepare a rough order-of-magnitude (ROM) estimate in the starting-the-project phase.

Use this estimate (from the preceding section) to decide whether the organization should consider your project further by entering the organizing-and-preparing phase.

Rather than an actual estimate of costs, this number often represents an amount that your project can’t exceed in order to have an acceptable return for the investment. Your confidence in this estimate is low because you don’t base it on detailed analyses of the project activities.

Rather than an actual estimate of costs, this number often represents an amount that your project can’t exceed in order to have an acceptable return for the investment. Your confidence in this estimate is low because you don’t base it on detailed analyses of the project activities.Develop your detailed budget estimate and get it approved in the organizing-and-preparing phase after you specify your project activities.

See the next section for more information on estimating project costs for this phase.

Check with your organization to find out who must approve project budgets. At a minimum, the budget is typically approved by the project manager, the program manager (if one exists), the head of finance, and possibly the project manager’s supervisor. The project’s Steering Committee might also be required to approve budgets.

Check with your organization to find out who must approve project budgets. At a minimum, the budget is typically approved by the project manager, the program manager (if one exists), the head of finance, and possibly the project manager’s supervisor. The project’s Steering Committee might also be required to approve budgets.Review your approved budget in the carrying-out-the-work phase — when you identify the people who will be working on your project and when you start to develop formal agreements for the use of equipment, facilities, vendors, and other resources.

Pay particular attention to the following items that often necessitate changes in the budget approved for the project:

- People actually assigned to the project team are more or less experienced than originally anticipated.

- Actual prices for goods and services you’ll purchase have increased.

- Some required project non-personnel resources are no longer available when you need them.

- Your clients want additional or different project results than those they originally discussed with you.

Get approval for any required changes to the budget or other parts of the approved plan before you begin the actual project work.

Submit requests for any changes to the original plan or budget to the same people who approved the original plan and budget.

Be sure to document any and all, big and small, changes in project scope, even if they do not warrant a budget change. This can help to avoid misunderstandings later when you attempt to bring the project to closure.

Be sure to document any and all, big and small, changes in project scope, even if they do not warrant a budget change. This can help to avoid misunderstandings later when you attempt to bring the project to closure.Monitor project activities and related occurrences throughout the carrying-out-the-work and closing-the-project phases to determine when budget revisions are necessary.

Check out Chapter 14 for how to monitor project expenditures during your project’s performance and how to determine whether budget changes are needed. Submit requests for necessary budget revisions as soon as possible to the same people you submitted the original budget to in Step 2.

Determining project costs for a detailed budget estimate

After you prepare your rough order-of-magnitude estimate and move into the organizing-and-preparing phase of your project, you’re ready to create your detailed budget estimate. Use a combination of the following approaches to develop this budget estimate:

- Bottom-up: Develop detailed cost estimates for each lowest-level work package in the WBS (refer to Chapter 6 for more on the WBS) and sum these estimates to obtain the total project budget estimate.

- Top-down: Set a target budget for the entire project and apportion this budget among all Level 2 components in the WBS. Then apportion the budgets for each of the Level 2 components among its Level 3 components. Continue in this manner until a budget has been assigned to each lowest-level WBS work package.

The bottom-up approach

Develop your bottom-up budget estimate by doing the following:

For each lowest-level work package, determine direct labor costs by multiplying the number of hours each person will work on it by the person’s hourly salary.

You can estimate direct labor costs by using either of the following two definitions for salary:

You can estimate direct labor costs by using either of the following two definitions for salary: - The actual salary of each person on the project

- The average salary for people with a particular job title, in a certain department, and so on

Suppose you need a graphic artist to design PowerPoint slides to support your presentation. The head of the graphics department estimates the person will spend 100 person-hours on your project. If you know that Harry (with a salary rate of $30 per hour) will work on the activity, you can estimate your direct labor costs to be $3,000. However, if the department head doesn’t know who’ll work on your project, use the average salary of a graphic artist in your organization to estimate the direct labor costs.

For each lowest-level work package, estimate the direct costs for materials, equipment, travel, contractual services, and other non-personnel resources.

See the earlier section “Determining Non-Personnel Resource Needs” for information on how to determine the non-personnel resources you need for your project. Consult with your procurement department, administrative staff, and finance department to determine the costs of these resources.

Determine the indirect costs associated with each work package.

You typically estimate indirect costs as a fraction of the planned direct labor costs for the work package. In general, your organization’s finance department determines this fraction annually by doing the following:

- Estimating organization direct labor costs for the coming year

- Estimating organization indirect costs for the coming year

- Dividing the estimated indirect costs by the estimated direct labor costs

You can estimate the total amount of indirect costs either by considering that they’re all in a single category labeled “indirect costs” or that they can be in one of the two separate categories labeled “overhead costs” and “general and administrative costs” (see the earlier section “Looking at different types of project costs” and the nearby sidebar “Two approaches for estimating indirect costs” for more information). If your organization doesn’t require that you use one or the other of these two approaches for estimating your project’s indirect costs, choose the one you’ll use by weighing the potential accuracy of the estimate against the effort to develop it.

Suppose you’re planning a project to design and produce a company brochure. You already have the following information (Figure 9-4 illustrates this information in a typical detailed budget estimate):

- You estimate that you’ll spend 200 person-hours on the project at $30 per hour and that Mary will spend 100 person-hours at $25 per hour.

- You estimate that the cost of the stationery for the brochures will be $1,000.

- You estimate $300 in travel costs to visit vendors and suppliers.

- You expect to pay a vendor $5,000 for the brochure’s artwork.

- Your organization has a combined indirect-cost rate of 60 percent of direct labor costs.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 9-4: A project budget estimate for a company brochure.

The top-down approach

To develop a budget using the top-down approach, you need two pieces of information:

- The amount you want to spend for the job

- The relative amounts of the total project budget that were spent on the different WBS components of similar projects

You then proceed to develop the budget for your project by allocating the total amount you want to spend on your project in the appropriate ratios among the lower-level WBS components until you’ve allocated amounts to all the work packages.

Relating This Chapter to the PMP Exam and PMBOK 7

Table 9-1 notes topics in this chapter that may be addressed on the Project Management Professional (PMP) certification exam and that are included in A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, 7th Edition (PMBOK 7).

TABLE 9-1 Chapter 9 Topics in Relation to the PMP Exam and PMBOK 7

Topic | Location in This Chapter | Location in PMBOK 7 | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

Techniques for determining and displaying non-personnel resources | 2.4.2.2. Estimating | Both books specify the same types of resources that should be planned and budgeted for. This book discusses formats for organizing and presenting information about needed non-personnel resources. | |

Techniques and approaches for estimating project costs and developing the project budget | “Recognizing the three stages of a project budget,” “Refining your budget as your project progresses,” and “Determining project costs for a detailed budget estimate” | 2.4.2.2. Estimating 2.4.2.4. Budget 4.4.2. Estimating | Both books mention similar categories of costs to be considered and the same evolving approach to developing a budget estimate that starts with rough estimates and refines them as more information is acquired. |