Chapter 3

Beginning the Journey: The Genesis of a Project

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Gathering information and preparing the business case

Gathering information and preparing the business case

![]() Working on the project charter and generating documents

Working on the project charter and generating documents

![]() Choosing which proposed projects will move to the second stage of their life cycle

Choosing which proposed projects will move to the second stage of their life cycle

![]() Tailoring approach, governance, and processes for the environment and work at hand

Tailoring approach, governance, and processes for the environment and work at hand

![]() Identifying the models, methods, and artifacts for your project

Identifying the models, methods, and artifacts for your project

If you typically deal with relatively short, inexpensive, straightforward projects, you may feel that the life of a project begins the moment your manager assigns it to you. You may not think it’s necessary to spend a lot of time deciding whether to perform the project, when such analysis will probably take more time than the project will to complete. And you may feel that, even if the project isn’t successful, no more than a few dollars and a couple of days will have been spent on it, so what’s the big deal?

Organizations today use projects as a major vehicle to maintain, support, enhance, and improve all facets of their operations. To help ensure the greatest possible benefits are realized from the resources they expend to support these projects, it’s essential that organizations undertake those projects that will both produce the greatest benefits when successfully completed and have the highest likelihood of achieving that successful completion.

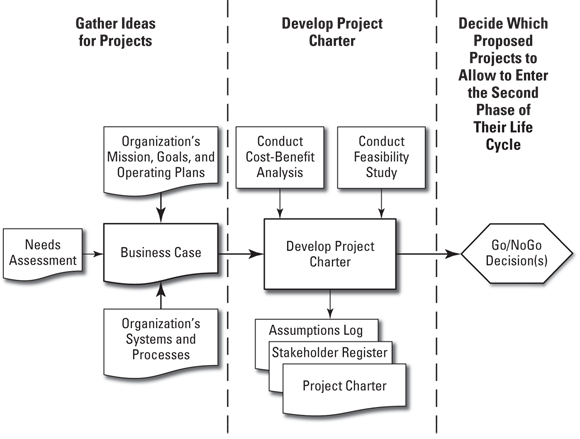

The steps that comprise the first phase of the project life cycle (starting the project) are depicted in Figure 3-1 (check out Chapter 1 for information on the project life cycle). As the figure depicts (and this chapter explains):

- Information about ideas for possible projects is identified and gathered.

- Any information required to enable a thorough evaluation of a possible project that’s missing from the initial information gathered is added.

- Projects that will proceed to the next phase of their life cycle (organizing and preparing) are chosen.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 3-1: The steps in Stage 1 of a project’s life cycle (starting the project).

Gathering Ideas for Projects

Sometimes a terrific idea for a project just pops into your head. However, though you always want to allow for unplanned, spontaneous creativity, most successful organizations choose to pursue a more carefully thought-out process for investigating those information sources that’ll most likely highlight projects that will be of greatest value to them.

Looking at information sources for potential projects

Organizational leaders initiate projects in response to one of the following four categories of factors that influence their organization:

- Regulatory, legal, or social requirements

- Stakeholder requests or needs

- Implementing or changing business or technological strategies

- Creating, fixing, or improving products, processes, or services

Important sources of information regarding possible projects and their potential value to the organization are the annual plans and budgets of the overall organization and its individual operating units. These documents typically include

- The organization’s (or unit’s) mission, goals, and strategies

- Desired changes to be made in the organization’s operations

- Changes occurring in the organization’s market, customers, and competition

- The organization’s key performance indicators (KPIs)

Other important sources of information include descriptions of the structure, components, problems, and issues related to the organization’s major operating systems and processes.

Proposing a project in a business case

The initial information describing a proposed project is often presented in a business case, which may contain, but isn’t limited to, the following:

- High-level statement of the business needs

- Reason action is needed

- Statement of business problem or opportunity the proposed project will address

- Stakeholders affected (see Chapter 4 for details on stakeholders)

- How it fits into the organization’s (product) roadmap

- Scope of proposed project (see Chapter 5 for information on scope statements)

- Analysis of situation

- Statement of organizational goals, strategies, and objectives

- Statement of the root causes behind the problem or factors helping to create the opportunity

- Discussion of the organization’s current performance in this area compared with the desired performance

- Identification of known risks for the project (see Chapter 10 for more on handling risk)

- Identification of critical success factors for the project

- Identification of the decision criteria for choosing among the different possible options for addressing the situation

- Discussion of the recommended course of action to pursue in the project

If necessary, a formal needs assessment may be conducted to clarify the business needs to which this project relates. A needs assessment (also called a gap analysis) is a formal study to determine the actions an organization must take to move from the currently existing situation to what’s desired in the future. This study consists of the following components:

- Defining the aspect of organizational operations you want to address and the measures you’ll use to describe performance in this area (this identifies the subject of your analysis)

- Determining the current values of the measures you selected in the first step (this defines the current state)

- Defining the values of the measures you would like to have exist in the future (this describes the desired state)

- Identifying the gaps that exist and need to be filled between current state and future state

- Proposing actions that will help the organization move toward the desired future situation (these are the steps to get from current state to future state)

- Clearly describe the project’s intended outcomes

- Identify the organization’s mission, goals, and operating objectives that’ll be affected by the project’s results

- Identify other projects addressing the same or similar issues that have been completed, are underway, are being planned, or are being proposed and clearly explain why this project will provide greater benefit when completed and has a greater likelihood of being successfully completed

- Dates by which your submission must be received

- Topics that must be addressed and/or formats in which your submission should be prepared

- Criteria (and relative weightings) that’ll be used to evaluate your submission

Developing the Project Charter

After it’s received, the business case for a project should be reviewed to determine its conformance with the organization’s needs and priorities. If the initial submission is approved, a project charter is prepared (by the project manager) containing all the information required to decide whether the project should proceed to the organizing- and-planning phase of its life cycle. The project charter, when approved, authorizes the existence of a project and provides the project manager with the authority to use organizational resources to support the performance of project activities.

The project charter may include, but is not limited to, the following information about the products, services, or other results the project will produce:

- Project name

- Project purpose

- Assigned project manager, responsibility, and authority level

- Name and authority of the sponsor(s) authorizing the project

- High-level project description, boundaries, and key deliverables

- High-level business requirements

- Measurable project objectives and corresponding success criteria

- Project approval requirements (who decides the project is successful and who signs off on the results)

- Summary milestone schedule

- Preapproved financial resources (budget)

- Overall project risk

- Key stakeholder list

- Project exit criteria

Two studies that may be performed to generate additional insight into the potential value and likelihood of success of the project being considered are a cost-benefit analysis and a feasibility study. The following sections discuss the types of information each seeks to provide and describe the documents produced during the development of a project charter.

Performing a cost-benefit analysis

A cost-benefit analysis is a comparative assessment of all the benefits you anticipate from your project and all the costs required to introduce the project, perform it, and support the changes resulting from it. Cost-benefit analyses help you:

- Decide whether to undertake a project or decide which of several projects to undertake

- Frame appropriate project objectives

- Develop appropriate before and after measures of project success

- Prepare estimates of the resources required to perform the project work

You can express some anticipated benefits in monetary equivalents (such as reduced operating costs or increased revenue). For other benefits, numerical measures can approximate some, but not all, aspects. If your project is to improve staff morale, for example, you may consider associated benefits to include reduced turnover, increased productivity, fewer absences, and fewer formal grievances. Whenever possible, express benefits and costs in monetary terms to facilitate the assessment of a project’s net value.

- Potential costs of not doing the project

- Potential costs if the project fails

- Opportunity costs (in other words, the potential benefits if you had spent your funds successfully performing a different project)

The further into the future you look when performing your analysis, the more important it is to convert your estimates of benefits over costs into today’s dollars. Unfortunately, the further you look, the less confident you can be of your estimates. For example, you may expect to reap benefits for years from a new computer system, but changing technology may make your new system obsolete after only one year. Thus, the following two key factors influence the results of a cost-benefit analysis:

- How far into the future you look to identify benefits

- The assumptions on which you base your analysis

Although you may not want to go out and design a cost-benefit analysis by yourself, you definitely want to see whether your project already has one and, if it does, what the specific results of that analysis were.

The excess of a project’s expected benefits over its estimated costs in today’s dollars is its net present value (NPV). The net present value is based on the following two premises:

- Inflation: The purchasing power of a dollar will be less one year from now than it is today. If the rate of inflation is 3 percent for the next 12 months, $1 today will be worth $0.97 one year from today. In other words, 12 months from now, you’ll pay $1 to buy what you paid $0.97 for today.

- Lost return on investment: If you spend money to perform the project being considered, you’ll forego the future income you could earn by investing it conservatively today. For example, if you put $1 in a bank and receive simple interest at the rate of 3 percent compounded annually, 12 months from today you’ll have $1.03 (assuming zero-percent inflation).

To address these considerations when determining the NPV, you specify the following numbers:

- Discount rate: The factor that reflects the future value of $1 in today’s dollars, considering the effects of both inflation and lost return on investment

- Allowable payback period: The length of time for anticipated benefits and estimated costs

In addition to determining the NPV for different discount rates and payback periods, figure the project’s internal rate of return (the value of discount rate that would yield an NPV of zero) for each payback period.

Conducting a feasibility study

A feasibility study, also called a proof-of-concept or POC, is conducted to determine whether a proposed project can be carried out successfully, whether the results the project provides can be used, and whether the project seems to be a reasonable approach to the problem it’s designed to address.

- Technical: Does the organization have access to the technical resources (such as people, equipment, facilities, raw materials, and information) at the times they’re needed to successfully perform the project tasks? (See Chapter 8 for information on human resources and Chapter 9 for information on equipment, facilities, raw materials, and information.)

- Financial: Can the organization provide the funds in the amounts and at the times they’re needed to perform the project tasks? (See Chapter 9 for information on project funds.)

- Legal: Can the organization satisfy any legal requirements or limitations that may affect the performance of the project work or implementation of its results?

- Operational: Can the results produced by the project satisfy the organizational needs the project is designed to address?

- Schedule: Can the work of the project be completed in the time allotted? (See Chapter 7 for information on developing the project schedule.)

Generating documents during the development of the project charter

Three documents are generated at the completion of the development of the project charter:

- The project charter itself: A list of the information typically included in the project charter is included at the beginning of this section.

- An initial version of a stakeholder register: A register of people or groups that are needed to support, affected by, or interested in your project. A stakeholder can be classified as a driver (someone who has some say in defining the results your project is to produce), a supporter (a stakeholder who helps you perform the project), or an observer (someone who is interested in your project, but is neither a driver nor a supporter). (See Chapter 4 for more information on project stakeholders.)

- An assumptions list: A list of statements about project information that people consider to be true, even though they have not been proven to be. The assumptions you make about project information that’s important but about which you’re uncertain can dramatically affect every aspect of your project planning, tracking, and analysis. Equally as problematic is the information you believe to be true but is actually based on someone else’s assumption or on a faulty source. Therefore, it’s critical to begin to maintain a list of project information you know to be assumed in the early stages of the development of project materials and to continually add to and delete from it as necessary throughout the project.

Deciding Which Projects to Move to the Second Phase of Their Life Cycle

The decision whether or not to allow a proposed project to proceed to the next phase of its life cycle is the last step of the first stage of the project’s life cycle (starting the project). The last step of one phase that leads to the first step of another phase is called a phase gate.

To maintain control over the progress of a project, it’s essential to assess how a project has progressed as measured by its key performance indicators (KPIs) and only to allow those projects that have met or exceeded their performance targets to proceed to the next phase. If one or more of a project’s KPIs do not meet the established standards, the organization must decide whether to have the project remain in its current stage and work to improve the unacceptable KPIs to acceptable levels, or whether to cancel the project completely.

Projects are evaluated in one of two ways in order to determine whether they should be allowed to proceed to their next phase:

- Individually, against a set of minimum acceptable values of the established project descriptive and performance data that must be achieved for a project to proceed to the next phase.

- In a group with one or more other projects — first, as described in the preceding bullet, to identify those projects that meet the minimum requirements for proceeding to the next phase, and second, to determine the relative rank in each of the descriptive and performance data categories that met the minimum standards.

The decision about which projects will proceed to the organizing-and-preparing phase of their life cycle (commonly referred to as a “Go/No-Go Decision”) will be based on the total amount of funds available to support the type of projects proposed in this group and the relative rankings of the desirability of each of the projects.

Tailoring Your Delivery Approach

You’ve probably already figured out that very rarely are two projects ever the same. Even projects with the same scope, stakeholders, schedule, and budget yield different outcomes when external factors differ from one project to the next. Since so few projects fit into a precise, repeatable mold, why then would you use the same approach, methods, and artifacts (to name a few) to manage every project? The answer is you wouldn’t. The concepts covered up to this point can be universally applied to all projects. Many other project factors, however, are better suited for some projects and organizations than others.

Nearly everything you use to manage your project can and should be tailored, including:

- Life cycle and delivery approach

- Processes

- Engagement

- Tools

- Models, methods, and artifacts

Let’s deconstruct these project factors to understand what each entails and the value each offers.

- The life cycle and delivery approach is one of the most impactful factors to tailor. Approaches range from predictive (Waterfall) to adaptive (Agile) with various hybrid models in between that each utilize different aspects of predictive and adaptive approaches (see Chapter 18 for more on Agile methodology). The approach you elect to use at this stage will set the foundation for the rest of your project.

- Processes are added to bring more control or address unique product or environment conditions and requirements; they are modified to better suit the project or project team requirements; they are removed to reduce cost or effort when the benefit they offer does not justify the cost to keep them; they are blended to enhance other processes by incorporating select elements that add the most value; and finally, they are aligned to ensure they have consistent definition, understanding, and application.

- Engagement tailoring addresses people, empowerment, and integration. People (project team and leadership) should be evaluated for their skills and capabilities and selected for the project based on their ability to complement each other and round out the team; empowerment involves the project responsibilities and the decision-making authority that resides with the project team or is reserved for leadership; integration considers all contributors to the project, internal and external (i.e., subcontractors, channel partners, and vendor partners, to name a few), and aims to bring them all together as a unified team working toward a common goal.

- Tools that the team will use to manage the project, such as software applications and equipment, can also be tailored. Two factors that most often influence which tools are best suited for a project are cost to procure or use the tools and the familiarity of the project team and stakeholders with the tools.

- The strategies, or models, to explain project processes, the means, or methods, to achieve project outcomes and the documents, templates, and presentations, or artifacts, to be prepared and used or delivered during the project should be tailored to include only those that add more benefit than the cost required to prepare and maintain them.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 3-2: The tangible and intangible benefits of tailoring a project.

For the organization

Organizations have internal processes, constraints, and requirements — the “guard rails” within which projects are expected to operate — even where the project team has authority and autonomy. Additionally, external factors such as environmental or regulatory restrictions often exist to which an organization is ultimately held accountable. Projects must be tailored to ensure that organizational needs are satisfied.

Let’s consider an organization that provides contract engineering services to government clients and similar services to private sector clients. The government clients require stringent time-keeping practices and routinely subject their vendors to financial audits. Failing an audit would result in the loss of the government business so, for this reason, the organization requires all associates to log all time, for all projects (government and private), to the nearest 15-minute increment.

The resources on your project to design, build, and deliver a custom software application for a fixed fee, to a private sector client, must adhere to the same organizational requirement. Your private sector client is not aware of the actual number of hours your team expends to deliver their custom software application nor is that information of interest to them. Your client is concerned that their software application is delivered on schedule for the agreed-upon fee, and that it satisfies the business requirements they provided. Rigorous timekeeping does not add value to your project or for your client, yet you must ensure that project team members record their time in accordance with your organization’s policy. This is an example of tailoring your project to satisfy organizational requirements.

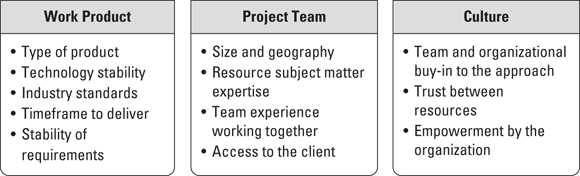

For the project

Just as you tailor your project for the organization, you also tailor for aspects of the project itself, including the work product to be delivered, the project team, and the culture. Figure 3-3 lists many (certainly not all) attributes of the output, the project team, and the culture that are considered when tailoring your project.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 3-3: Tailoring for the project can include and be influenced by one or many factors.

As discussed a few moments ago, nearly every aspect of a project can and, where applicable, should be tailored to ensure the framework you use is optimized for your project and organization. The more effort you dedicate early on to properly tailoring your project, the smoother your project will be.

Identifying the Models, Methods, and Artifacts to Use

We discussed the value you can realize by tailoring the models, methods, and artifacts that you use to manage your project. Now, let’s review some examples of those models, methods, and artifacts.

In lieu of a deep dive into each model, we cover some of the most used model types in project management:

- Situational leadership models are one type of leadership model that describes how you can tailor your leadership style to best suit your project team and team members. Situational leadership models, and leadership models in general, are inherently fluid and dynamic, as they offer a framework for responding to different and often changing situations and personalities.

Effective communication is paramount to leading a successful project and communication models consider the different frames of reference of all parties to facilitate this effective communication. The sender of a message most likely brings with them a different perspective than the intended recipient of that message. The background, experiences, and culture of a recipient could notably impact how they receive, interpret, and react to a message. A critical element of communications, nowadays more than ever, is the channel through which that communication occurs. Whether you communicate face-to-face, by telephone, email, instant message, text message, blog, wiki, social media post, or old-fashioned smoke signals, your message could be received and interpreted differently than you intend.

The most important consideration when choosing your mode of communication is whether it is situationally appropriate and likely to be interpreted by your recipient as intended. Beyond that, use whatever means of communication is easiest and most convenient for you and your team. In the end, if you’re able to reliably relay the meaning and tone of your message to the correct recipient who is similarly able to accurately receive and interpret it, you’ve chosen an effective communication model for your project.

Your ability to motivate your team is arguably as important as how effectively you communicate with them. Motivation models address what drives people and how you can use that knowledge to your advantage. When you motivate, you create desirable outcomes that contribute to a mutually beneficial arrangement (your resource is motivated to achieve those desirable outcomes and, in doing so, provides a similarly desirable outcome for you and your project).

People are often motivated by different factors. Where some are motivated at work by their ability to achieve, grow, and expand their knowledge base, others are motivated by salary, a corner office with a view, or an impressive job title. Where some are motivated by their ability to master a particular skill or to make a meaningful contribution to a larger team effort, others are motivated by their ability to define their own work hours, work from home when they prefer, or choose the projects to which they contribute. It doesn’t matter if you agree with what motivates another person – respect that what motivates them is unique and specific to them and find a way to deliver it so they will ultimately return the favor.

Change models describe necessary activities to achieve successful change management. As with the model types discussed so far, there are many different change models, so let’s focus on some of the common and widely applicable characteristics. It is important to start with a sense of urgency to drive the need for change. Sir Isaac Newton’s First Law of Motion tells us that a body at rest tends to stay at rest, and a body in motion tends to stay in motion, unless acted upon by some outside force. This applies to human behavior as well. People typically gravitate toward a path that upholds the status quo unless you can provide them a compelling reason to change.

Depending on your team dynamic, it can be helpful or even essential to form a coalition of influencers who have already accepted the need to change and can help bring other team members along for the ride. Change can often be a lengthy and arduous process, but this can largely be mitigated by creating near-term wins, often referred to as “low hanging fruit” or “quick hits.” While the metaphor of running a marathon is a bit overdone and even cliché at this point, it remains pertinent. For example, running the Boston marathon can be a daunting thought for even the most experienced and well-trained athletes. Breaking the course down into more “bite size” one-mile increments can be more manageable for some (and easy to track since there are mile markers and water stations at each mile). As you lead your team through difficult project tasks, keep in mind that, while it is important to keep your eye on the bigger picture, your team won’t last long enough to achieve the bigger picture if they lose their steam along the way.

- Project team development models help you assess your team’s maturity to empower you to further their growth and development throughout the project life cycle. Models of this type follow a similar framework: First, the team comes together; next, the team figures out who’s who and what’s what; next, the team finds their groove; finally, the team completes their mission and moves onto other projects. This is an intentionally oversimplified description because, as with many of the other types, these models are differentiated by their details and nuances. Some models focus more on interpersonal dynamics and development into a cohesive unit; others focus more on the team’s output and their ability to produce increasingly high-quality results as they become more accustomed to working together. Familiarize yourself with the project team development models described in PMBOK 7, specifically, and other literature, in general, so you are informed when you choose the aspects of each model that resonate as you build and nurture your teams.

- Data gathering and analysis: You are already familiar with several methods in this category, like the business case, cost-benefit analysis, feasibility study, and stakeholder analysis (part of creating the project charter covered earlier in this chapter). Data gathering and analysis methods help you collect, analyze, and evaluate facts and data to provide insight into a particular situation.

- Estimating: Some commonly used estimating methods include story point estimating in Agile Project Management (see Chapter 18 for more on Agile), affinity grouping (such as “T-shirt sizing”), and analogous estimating. Analogous estimating uses tasks and projects performed previously to inform estimates for similar tasks and projects to be performed. Generally, estimating methods facilitate your approximation of effort, duration, or cost.

- Meeting and events: You’re probably familiar, perhaps all too familiar, with the meetings you conduct throughout your projects. It is important to balance the need to engage and communicate with various stakeholder groups during a project with the risk of inducing “meeting fatigue” or “meeting overload” and detracting from the execution of the project work itself. That said, meetings and events are critical to project success, so let’s review some of the key ones that add value to nearly all projects:

- Kickoff meeting: Formally starts the project (or a specific phase of the project) and aligns the team and key stakeholders to the project’s goals and expectations.

- Standup meeting: A brief, usually 15 minute, daily session where you review progress from the prior day, review planned work for the current day, and call out any obstacles that might impede the team’s future progress. In Agile, this is called the “daily scrum.”

- Iteration/milestone/phase/Sprint review: This meeting is conducted once all the work for a specific phase of the project has been completed. Depending on the type of project, this review may include a demonstration and often culminates in a go/no-go decision to proceed to the next phase of the project.

- Status meeting: An opportunity to update stakeholders and review progress to date, status meetings are often accompanied by a status report, to indicate performance against budget, schedule, and milestones that may be reviewed with the attendees.

- Steering committee meeting: Comprised of senior-level stakeholders (from the client, your organization, and even vendors and contractors when appropriate) who provide direction and support to the project team and are empowered to make decisions outside of the project team’s authority.

- Project retrospective: Often referred to as a project post-mortem, a lessons learned meeting, or a project review and closeout meeting, a retrospective takes an objective look at all aspects of a recently completed project for two purposes: first, to ensure that mistakes or undesirable outcomes are understood so they can be avoided in the future; and second, to ensure that positive accomplishments of the project are called out, celebrated, and able to be repeated in future projects.

- Strategy artifacts: Created prior to or at the onset of a project and referred to throughout the project to ensure they are satisfied by the project output. Examples include:

- Business case: See “Proposing a project in a business case” section earlier in this chapter for details.

- Project charter: See “Developing the Project Charter” section earlier in this chapter for details.

- Roadmap: A high-level timeline that shows milestones, key review and decision points, and is often subdivided into more manageable phases.

- Logs and registers: Ongoing records of continuously evolving factors. Examples include:

- Risk register: Risks, actions, issues, and decisions are often consolidated into a single log, called the RAID log. See the section “Preparing a Risk Management Plan” in Chapter 10 for more on risks.

- Issue log: The previous comment for risk register also applies to the issue log.

- Stakeholder register: More than just a contact list, this register classifies and assesses each stakeholder for the role they play in their organization and on the project. See Chapter 4 for more on this.

- Plans: Proposed means to achieve project goals. Examples include:

- Communications plan: Describes how, when, and by whom project communications will be disseminated. See Chapter 15 for more on this.

- Resource management plan: Explains how resources are identified, onboarded (or procured), supported (or maintained), and managed (or utilized) throughout the project. See Chapter 8 for more on human resource management (and Chapter 9 for non-personnel resource management).

- Risk management plan: Defines how risk will be triaged, classified, and addressed. See Chapter 10 for more on this.

- Change control plan: Presents the process to document, assess, and implement changes, whether they have a contractual or other impact to the project or not. See Chapter 14 for more on change control.

- Hierarchy charts: High-level info broken down into levels of increasingly greater detail. Examples include:

- Work breakdown structure (WBS): One of the most universally applicable and fundamental project management artifacts, the WBS decomposes the overall project scope into lower-level (and more detailed) tasks. Your goal should always be to define your WBS down to the most granular level of detail possible. See Chapter 14 for more on this.

- Organizational breakdown structure: Not to be confused with an “org chart,” this chart represents the relationship between tasks or activities and the organizational units assigned to them.

- Baselines: Approved plans against which progress is tracked to help identify and quantify variances. Examples include:

- Project schedule: Sometimes called a project plan and often presented in the form of or in conjunction with a Gantt chart, the project schedule illustrates linked tasks with planned dates, durations, milestones, and resource assignments. See Chapter 7 for more on this.

- Budget: The approved cost estimate for the project or component of your WBS. See Chapter 9 for more on this.

- Visual data and information: Charts, graphs, and diagrams to graphically present complex data in a visual manner that can be easier to digest and interpret. Examples include:

- Gantt chart: A graphical illustration of the project schedule that visually indicates task durations and dependencies throughout the project timeline. See Chapter 7 for more on this.

- Responsibility assignment matrix (RAM): One of the most common versions of a RAM is the RACI, which defines who is responsible, accountable, consulted, or informed for or about project activities, decisions, and deliverables. See Chapter 12 for more on this.

- Dashboards: Graphical representations of project metrics and KPIs that provide at-a-glance views of overall status. See Chapter 15 for more on this.

- Reports: Formal records of pertinent project information. Examples include:

- Status report: Usually includes progress made since last report, activities planned until the next report, budget and schedule status, risks and issues. See Chapter 15 for more on this.

- Quality report: Documents any quality management issues, corrective actions and recommendations for process, project, and product improvements to prevent similar quality issues from recurring.

- Agreements and contracts: Documentation of agreed-upon intentions and expectations between multiple parties. Examples include:

- Fixed-price contracts: These contracts define a deliverable and a price to be paid for that deliverable. As long as the project scope adheres to the contractually defined scope, the price does not change. Changes to scope are handled through change orders.

- Time and materials contracts: T&M contracts require each hour spent working on the project to be logged and invoiced to the client, including any materials or expenses required to satisfy the contract. These contracts often contain a not-to-exceed clause. This clause specifies the maximum number of hours to be invoiced to the client, assuming scope has not changed, before a new contract for any remaining or additional work is executed.

- Change orders: We all hope to be able to foresee every possible “gotcha” that could arise before our projects even begin but, alas, hope is never a winning strategy. When scope changes, change orders capture the nature of the change and any associated budget, schedule, or resource implications. See Chapter 14 for more on this.

- Other artifacts: Some artifacts don’t fit into one of the previous buckets, but are useful and add value, nonetheless. Examples include:

- Bid documents: Help to answer necessary questions to enable an informed procurement decision, including request for information (RFI), request for quotation (RFQ), and request for proposal (RFP).

- Requirements document: Depending on the type of project, this is often broken down further into a business requirements document, functional requirements document, and technical requirements document. See Chapter 5 for more on this.

Relating This Chapter to the PMP Exam and PMBOK 7

Table 3-1 notes topics in this chapter that may be addressed on the Project Management Professional (PMP) certification exam and that are also included in A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, 7th Edition (PMBOK 7).

TABLE 3-1 Chapter 3 Topics in Relation to the PMP Exam and PMBOK 7

Topic | Location in This Chapter | Location in PMBOK 7 | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

Business case | 2.6.1 Delivery of Value | PMBOK 7 discusses the business case as a tool to justify a project and assess anticipated business value in a manner that can be periodically measured to understand ongoing project health. | |

Project charter | 4.6.1 Strategy Artifacts | The project charter is referenced in PMBOK 7, but without much detail. | |

Cost-benefit analysis | 4.4.1 Data Gathering and Analysis | Similarly, cost-benefit analysis is mentioned in PMBOK 7 but at a high level and without much detail. | |

Feasibility study | 2.3.5 Life Cycle and Phase Definitions | PMBOK 7 covers feasibility as a phase in a project life cycle but does not mention a feasibility study directly. | |

Tailoring | Section 3: Tailoring | A new section is dedicated to tailoring in PMBOK 7, before which it was considered a component to address at the onset of each Knowledge Area rather than a stand-alone concept. Many examples of tailoring described in this chapter align with those described in PMBOK 7. | |

Models, methods, and artifacts | Section 4: Models, Methods, and Artifacts | Models, Methods, and Artifacts is afforded its own distinct section for the first time in PMBOK 7. |

The organization’s goal is to fund those projects that, when successfully completed, would provide the greatest benefits to the organization and have the greatest chances of being completed successfully. Therefore, the business case should do the following:

The organization’s goal is to fund those projects that, when successfully completed, would provide the greatest benefits to the organization and have the greatest chances of being completed successfully. Therefore, the business case should do the following:  The business case should be prepared by a person who is external to the project, such as a senior manager of the unit on which the project will focus or a product manager if one exists. The project initiator or sponsor should be at a level where they can procure funding and commit resources to the project.

The business case should be prepared by a person who is external to the project, such as a senior manager of the unit on which the project will focus or a product manager if one exists. The project initiator or sponsor should be at a level where they can procure funding and commit resources to the project. Beware of assumptions that you or others may make (sometimes without realizing it) when assessing your project’s potential value, cost, and feasibility. For example, just because your requests for overtime have been turned down in the past doesn’t guarantee they’ll be turned down this time. Have people write down all assumptions they make when analyzing or planning a project in an assumptions log (see the next section for details).

Beware of assumptions that you or others may make (sometimes without realizing it) when assessing your project’s potential value, cost, and feasibility. For example, just because your requests for overtime have been turned down in the past doesn’t guarantee they’ll be turned down this time. Have people write down all assumptions they make when analyzing or planning a project in an assumptions log (see the next section for details).