1 Why the world has failed to slow global warming

In the late 1980s the United Nations began the first round of formal talks on global warming. Over the subsequent two decades the scientific understanding of climate change has improved and public awareness of the problem has spread widely. These are encouraging trends. But the diplomacy seems to be headed in the opposite direction. Early diplomatic efforts easily produced new treaties, such as the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. Those treaties were easy to agree upon yet had almost no impact on the emissions that cause global warming. As governments have tried to tighten the screws and get more serious, disagreements have proliferated and diplomacy has stuck in gridlock.

My argument is that the lack of progress on global warming stems not just from the complexity and difficulty of the problem, which are fundamental attributes that are hard to change, but also from the failure to adopt a workable policy strategy, which is something that governments can change. Making that change will require governments, firms, and NGOs that are most keen to make a dent in global warming to rethink almost every aspect of conventional wisdom. In this chapter I will summarize my argument in six steps. My ultimate goal is Step 6—a suggestion for a new international strategy—but the first five steps are crucial for making the right moves in Step 6. For the last twenty years, diplomats focused too much on ideas for diplomatic strategies that were not rooted in a proper understanding of the underlying political, economic, and technological forces that drive real policy on climate change.1

Step 1, why the science of global warming matters

Any serious effort to slow global warming must start with one geophysical fact. The main human cause of warming is carbon dioxide (CO2). Other gases also change the climate, but compared with CO2 they are marginal players.2 Making a big dent in global warming requires making a big dent in CO2. Most of the economic and political challenges in slowing global warming stem from the fact that CO2 lingers in the atmosphere for a century or longer, which is why climate policy experts call it a “stock pollutant.” The stock of CO2 builds up from emissions that accumulate in the atmosphere over many years. As the stock rises global warming follows in tandem. Because the processes that remove CO2 from the atmosphere work very slowly, big changes in the stock require massive changes in emissions. Just stopping the build-up of CO2, for example, requires cutting worldwide emissions by about half. Lowering the stock, which is what will ultimately be needed to reverse global warming, demands even deeper cuts. Exactly how much of a cut will be needed is hard to pin down because the natural processes that remove CO2 are not fully understood. There is a chance they will become a lot less effective as the stock of CO2 rises, which would imply the need for even deeper cuts.

The most important geopolitical attribute of global warming—that the problem is global—follows directly from the fact that CO2 is a stock pollutant. Emissions waft throughout the atmosphere worldwide in about a year, which is much faster than the hundreds of years needed for natural processes to remove the excess CO2. Politically, this means that every nation will evaluate the decision to cut emissions with an eye on what other big emitters will do since no nation, acting alone, can have much impact on the planetary problem. Even the biggest polluters, such as China and the US, are mostly harmed by pollution from other countries that has wafted worldwide.

Society has addressed global stock pollutants before—such as the very successful efforts to control chlorofluorocarbons and other long-lived gases that deplete the ozone layer. What makes CO2 harder to manage is that it is intrinsically tied up in how society uses fossil fuels. Burning fossil fuels is a chemical reaction that releases CO2, and thus there is no easy way to fix the problem. Because our chief pollutant is CO2, we know that serious regulation will mainly focus on energy policies. Tinkering at the margins of the energy system will not make much of a difference. Deep cuts in CO2 will probably require a massive re-engineering of modern energy systems. Such an effort will alter how utilities generate electricity and the fuels used for transportation, among many other implications. Such a transformation is not impossible; in fact, over history it has happened several times.3 But no country—let alone the world community—has ever planned such a transformation in energy infrastructure. At this stage nobody knows what it will cost, but most likely it will be expensive. Some studies suggest the cost will be in the range of 1–2 percent of global GDP, but if policy is implemented poorly or troubles arise then that fraction could be even larger.4 Because energy systems are based on complicated infrastructures it is likely to unfold slowly. And because this transformation will require new technologies and business models that do not yet exist at scale the cost and complexity are hard to fathom. The pace of this transformation will be impossible to plan and predict to exacting timetables.

That is the first step. CO2 is a stock pollutant, and from that simple geophysical fact comes two important political insights: one is that regulation will require international coordination, and the other is that governments will have a hard time making credible promises about exactly how quickly they can make deep cuts in CO2. Because CO2 is interwoven with energy systems that are costly and sluggish to change, when governments tighten the screws on emissions—something that has not yet happened except in a very small number of countries—they will find it increasingly difficult to plan and adopt the policies needed to make a difference. As the cost of this transformation rises, what every country does will depend on confidence that other countries are making comparable efforts. Yet even governments working in good faith will be in the dark about what they can really deliver. Of all of the six steps I discuss in this chapter, this first step is the one that is most widely known; yet its profound implications for geopolitics and economics are still not properly appreciated. Climate change requires costly global collective action, and that is very hard to organize.

Step 2, myths about the policy process

Second, international coordination on global warming has become stuck in gridlock in part because policy debates are steeped in a series of myths. These myths allow policy makers to pretend that the CO2 problem is easier to solve than it really is. They perpetuate the belief that if only societies had “political will” or “ambition” they could tighten their belt straps and get on with the task. The problem is not just political will. It is the imaginary visions that people have about how policy works.

One is the “scientist’s myth,” which is the view that scientific research can determine the safe level of global warming. Once scientists have drawn red lines of safety, then everyone else in society optimizes to meet that global goal. The reality is that nobody knows how much warming is safe, and what society expects from science is far beyond what reasonable scientists can actually deliver. One consequence is that the science around global warming looks a lot more chaotic and plagued by disagreement than is really true. The climate system is intrinsically complex and does not lend itself to simple red lines; “safety” is a product of circumstances and interests. The result is an obsession with false and unachievable goals.

Over the last decade many scientists and governments have set the goal of limiting warming to 1.5 or 2 degrees, which has now become the benchmark for progress on global warming talks. Two degrees is particularly attractive because it is a simple number and it seems to be achievable; so far, actual measured warming is about one degree so it would seem that stopping at two is within reach. Unfortunately, this goal bears no relationship to emission controls that most governments will actually adopt. And it is not based on much science either since we do not really know what level of warming is safe; for some societies and fragile ecosystems the warming that is already built into the climate system is probably already dangerous. What worries me most, however, is the disconnect between abstract goals like 1.5 to 2 degrees and how real policy is likely to emerge in this field.

Serious policies to control emissions will emerge “bottom-up” with each nation learning what it can and will implement at home. Just as countries learn how to control emissions they will also look at the science, along with their own national vulnerabilities to climate change, and determine the level of warming they can stomach. It is highly unlikely that countries will arrive at the same answers.

It is important to puncture the “scientist’s myth” because it creates a false vision for the policy process—one that starts with global goals and works backwards to national efforts. When pollutants such as CO2 are the concern, real policy works in the opposite direction. It starts with what nations are willing and able to implement.

A similar myth explains much of diplomacy. Environmental diplomats imagine that progress toward solving problems of international cooperation hinges on the negotiation of universal, legally binding agreements that national governments then implement back at home. While the scientist’s myth starts with scientific goals and works backwards to national policy, diplomats make the same kind of error and start with binding international law and draw the same backward conclusion. Events like the Copenhagen Conference are the pinnacle of this mythical legal kingdom. When these events fail to produce consensus the diplomatic community does not shift course but merely redoubles its efforts to find universal, binding law.

The reality is that universal treaties are a very bad way to get started on serious emission controls. Global agreements make it easier for governments to hide behind the lowest common denominator. Binding treaties work well only when governments know what they are willing and able to implement. Universal binding law has played a useful role in some areas of international environmental cooperation, but the attributes of the climate change problem require a different approach.5

Finally, we must have a smarter perspective on technology. The “engineer’s myth” holds that once inventors have created cheaper new technologies, these new devices can quickly enter into service. This belief is appealing because it offers hope for quick and cheap solutions. It is also appealing because many engineers believe that the needed technologies already exist. Energy efficiency, for example, is widely believed to be a readily available option for making deep cuts in emissions at no cost. The reality is that much of the exciting potential for using energy more efficiently is not presently practical because the needed technologies are not yet married to how real firms and households use energy. Technological transformation is a slow process because it depends on a lot more than engineering. New business models and industrial practices are needed. The more radical (and useful in cutting the use of fossil energy and CO2) the innovation is, usually the greater the technological and financial risks. Putting those innovations into practice hinges on creating the policies and business practices to manage the risks—especially financial risks—that accompany new technologies. Even when those policies are written in treaty registers and in national laws and regulations, firms that invest in new technology and practices must believe they are credible. Pretending that engineering innovation is the key step leads to policy goals that are overly ambitious and divorced from the realities of what determines whether these new technologies will actually enter into service quickly. The engineer’s myth also allows governments to avoid grappling with the kinds of technology policies that will be needed to encourage radical innovation and deployment of new technologies to lower emissions. My assessment of the experience with energy policy to date is that fundamental innovation is relatively easy to steer. Creating the credible policy environment to encourage widespread adoption of innovations is almost always the weak link.6

That is the second step: we must clear away false models of the policy process and focus on how policy processes actually work. The first step laid bare the essence of the warming problem; the second step helps clear the landscape of confusing ideas. The rest of the chapter outlines a new vision.

Step 3, regulating emissions

The third step in the logic is the most important. Slowing global warming requires a big reduction in emissions of CO2. Achieving that goal will require international coordination. Before I focus on how to make effective international coordination, I must look closely at what individual national governments are willing and able to implement.

Oddly, most studies of international coordination on global warming ignore national policy and treat governments as “black boxes.” Few analysts of international relations and international law peer inside the box to discover how it works; most just imagine that the national policy process will behave as needed once people have political will. Black boxing national policy is convenient because it makes it easier to focus just on the simpler and sexier topic of international diplomacy. Such studies start by imagining various ideal mechanisms for international coordination and then expect that the black boxes will follow along with implementation. The reality is that the black boxes are prone to produce certain kinds of policies. Ignoring those tendencies raises the danger that international coordination will become divorced from what real governments can implement at home. These dangers were not much apparent in the early years of global warming diplomacy because international agreements were not very demanding. The black boxes could comply without doing much beyond what they would have done anyway. But as governments have tried to tighten the screws on emissions of warming gases, a huge gap has opened between the agreements that diplomats are trying to craft at the international level and what their own governments can credibly implement at home. That gap produces gridlock. It lowers confidence that international law is relevant, and as confidence declines governments become less willing to make risky, costly moves to regulate emissions. In the extreme, the result are agreements such as the Copenhagen Accord—legal zombies that have no relationship to what governments will actually implement yet are hard to kill or ignore. Crafting a more effective system of international coordination requires a vision for how to avoid such international outcomes.

The third step builds a simple theory of national policy. This theory begins with the interests of individuals, their beliefs, and how well they are organized. Politically viable policies to control emissions must avoid imposing high costs on politically well-organized large groups and also avoid making high costs evident to poorly organized but potentially dominant groups, such as voters. Policies that are politically viable will therefore not be identical with policies that are economically optimal, and in some cases the dispersion between the viable and the optimal will be huge. The result is that most countries have very strong incentives to adopt policies that look like they are having a practical impact on emissions when, in fact, they avoid imposing harm on well-organized interest groups. Since those interest groups often include the same activities that result in high emissions the result is a big gap between what countries promise to their electorates (and to each other in international negotiations) and what most of them can actually deliver. Knowing this, we need visions for international cooperation that are more likely to mesh with policies that real governments can actually implement at home.

One way to start analyzing the prospects for international cooperation is to focus on power, interests, and capabilities. Power tells us which countries really matter and must be engaged in coordination. Interests reveal what those countries will be willing to do. And capabilities are what they are actually able to do.

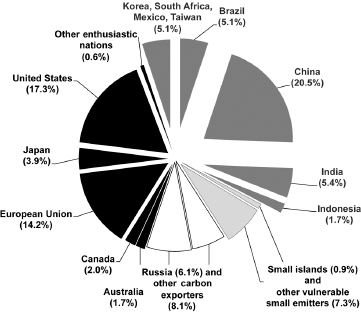

In global warming, power is first and foremost a function of current and future emissions. China and the United States are the most powerful countries on global warming because they have the largest emissions and thus the greatest ability to inflict global harm and avoid harm through their actions. Although the United Nations (UN) officially registers 192 countries on the planet, when it comes to emissions only a dozen or so really matter. I show those big emitters in Figure 1.1. Eventually, all governments will need to play a role in controlling emissions because even the big emitters will be wary about adopting costly policies if small countries become pollution havens. China, for example, will not be keen to control its emissions if the outcome is much higher costs of doing business in China and investments (along with jobs and incomes) “leak” to Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, or other countries that would become more formidable economic competitors without the burden of costly emission controls. I will deal with that problem in time, but getting started on controlling emissions requires a vision that is connected to the reality of how the most powerful countries—the biggest emitters—might actually control emissions at home.

Figure 1.1 National interests and emissions.

Note

1 The figure shows the most recent complete inventory for emissions of CO2 from burning fossil fuels and changes in land use. “Enthusiastic” countries are shown in black. “Reluctant” nations are shown in dark grey. Together, those twelve countries (treating the EU as one) account for 77 percent of emissions. Excluded from that group is the very large number of small countries (mainly low-income, developing countries) and countries that are large carbon exporters and under little public pressure to regulate emissions, such as Russia and the largest OPEC members. This data set includes full data for CO2 emissions from fossil fuels (drawn from the Carbon Dioxide Information and Analysis Center at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (Boden, et al. 2010) augmented with nationally reported data on emissions (and sinks) from land use (including forestry and agriculture) as reported in official emission inventories (see unfccc.int and also UNFCCC 2010). The land use data are 2006 for UNFCCC Annex I countries (i.e., industrialized nations); for non-Annex I countries land use data are 1994 except Mexico (2002) Korea (2001), and Kazakhstan (2005); failures to report data by Angola, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, and Qatar led me to exclude those countries from the analysis.

Whether big emitters actually control emissions is a function of their interests and capabilities. The full list of factors that determine interests is long, and scholars should spend more time trying to explain and predict the variation in national interests. Some countries are highly vulnerable to global warming, such as the low-lying island states; others, such as frigid Russia, are less worried or might even welcome a thaw. Rich countries are usually more worried than poor ones because wealth brings the luxury of focusing on more than just immediate survival. Democracies seem to be more concerned than non-democracies because the ability to organize interest groups and a free press are empowering to NGOs that carry the messages about warming dangers to people and governments around the world. Parliamentary systems are often more energized about warming than presidential governments when green parties become members of ruling coalitions. A nation’s interests also depend on what it thinks other countries will do. If one country thinks that emission controls at home will inspire other nations to follow suit it will be more keen to make the move. My home state of California is on the cusp of adopting costly state controls on CO2 with that theory in mind. A full-blown theory of national interests would need to look at all these factors.

I start by dividing the world into two categories: enthusiastic and reluctant countries. Enthusiastic countries are willing to spend their own resources to control emissions. These countries are the engine of international cooperation. The bigger that group and the more resources they are willing to spend on controlling emissions, the deeper the cuts in global emissions. Some of the troubles with global warming diplomacy during the last two decades simply reflected that the group of enthusiastic countries was pretty small and consisted of little more than a few EU members and Japan. But that group is getting bigger and now includes the US and essentially all members of the OECD. Not all these countries have the same interests, of course. What the US is willing to do is a lot more modest these days than the French, German or British effort. And what countries actually do is often not formally labeled climate policy. The US has struggled with national political gridlock on a federal global warming policy, but through direct regulation and many state policies it is making an effort—albeit one that falls short of what it should pursue.

The reluctant nations, such as China and India, also matter. They are already big emitters, and most studies suggest that such countries will account for essentially all growth in future emissions. Because these countries do not put global warming high on the list of national concerns, they will not do much to control emissions except where those efforts coincide with other national goals. Outsiders can change how these countries calculate their national interests by threatening penalties such as trade sanctions or offering carrots such as funding for investments that lower emissions. Outsiders can also provide information on global warming dangers, which will (in time) help reluctant countries see their interests differently. A country whose government and NGOs are better informed about the perils of unchecked climate change will be more likely to mobilize for change—especially if there is an international framework that would allow their national efforts to be magnified through efforts by other big emitters.

So far we have examined power and interests. Now let us focus on capabilities. In general, the enthusiastic countries have well-functioning systems of administrative law and regulation and can control all manner of economic activities within their borders. In reluctant nations those systems are generally much less well developed. Typically in the reluctant countries some sectors are under tight administrative control and others march to the beat of their own drummer.

Enthusiastic countries have lots of options for regulating their emissions. They could use market-based strategies, such as emission taxes or “cap and trade” schemes. Or they could use traditional regulation that, for example, forces companies, farmers, and consumers to utilize particular technologies and practices that reduce emissions. In the book on which this essay is based I show that the most likely outcome is a hybrid of emissions trading and regulation. Emission trading systems are attractive because they create extremely valuable assets (emission permits) that can be awarded to politically well-connected interest groups. Once the initial awards are made, those same groups become a powerful lobby to keep the system in place. Where these lobbies are well organized to manage a market that channels resources to themselves and prevent new entrants, emission trading is the policy instrument of choice. Where regulated firms have close ties to their regulators, then direct regulation is even better. Many environmental NGOs also like regulation because that approach makes it easier to hide and shift the cost of policy. The political viability of policies rises when the cost can be imposed on groups that are highly diffused and often unaware of what they are paying. Within this range of hybrid outcomes, every nation will make a different choice because each government faces differently arrayed interest groups and different relationships between organized group and government. I will call these hybrid outcomes “Potemkin markets” because on the surface they look like emission-trading-markets market solutions yet are designed, exactly contrary to the principle of markets, to hide the costs of action and to channel resources only to well-organized groups. This is a prediction of what governments will actually do in the real world as they start getting serious (or pretending to get serious) about controlling emissions. It is on full display today in the European Union which has allowed a region-wide market (the Emission Trading Scheme) to persist even though prices are so low that it has practically no effect on actual emitting behavior. What I am suggesting is not that Potemkin markets are good economic policy. In fact, as a policy analyst, I find that outcome deeply unsettling. A simple economy-wide cap and trade program would be more cost-effective, and even better than that would be a simple economy-wide emission tax. Ideal theory often clashes with political realities. One of the key insights is that international accords must be designed with flexibility for governments to adopt different kinds of Potemkin markets since that untidy outcome is unavoidable.

Reluctant nations are different. So far, these countries have not done much to control emissions for two reasons. One is that the enthusiastic nations have dithered in creating carrots and sticks that will convince these countries to see the world differently. The biggest existing carrot is the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), which is badly administered and creates perverse incentives for reluctant nations to avoid serious emission controls.7 Sticks, such as border adjustments and trade sanctions, are barely used at all. Better sticks and smarter carrots are needed. The second argument is that much more can be done to encourage these countries to implement policies that satisfy local goals, such as energy security and lower local pollution, while also fortuitously reducing emissions of warming gases. In other research, including the book, I have looked in detail at a sample of such opportunities, such as the deployment of more efficient technologies in coal-fired power plants, fuller use of natural gas (which has much lower emissions than coal), and better management of endangered forests.

The idea that there are huge “win–win” opportunities is hardly new. A big study organized by the World Bank, for example, has documented lots of ways that countries can meet their own local interests while also reducing emissions of warming gases.8 The options are numerous; many of them individually can save hundreds of millions of tons of CO2 emissions per year—numbers that are comparable with the entire worldwide effort under the Kyoto Protocol. Adding these up can result in perhaps 10–20 percent global reductions in emissions while putting the planet on a trajectory to lower future emissions. That is not enough to stop warming, which will require cuts of 50 percent over the next few decades, but it is a way to make tangible progress that is aligned with national interest. It is also a way to build credibility into international efforts on this important problem; such credibility, in turn, will make it easier for nations to coordinate on the harder task of cutting emissions in areas that do not immediately align with national self-interest and will require true collective action.

Oddly, the existing literature is largely silent on the question that matters most for policy: which “win–win” opportunities that exist in theory will actually be feasible in the real world? There are lots of things that governments can do in an imaginary world of perfect information, foresight, and ability, and most analysis of win–win options operates in that imaginary world. But the real world is different. For students of international cooperation, what is most striking is that, often, “win–win” policies are not pure winners on their own merits; they require outsiders to help with financing, technology, diplomatic support, or other assets. The problem is that the existing sticks and carrots are nearly always irrelevant to encouraging countries to implement these kinds of policies. Notably, the CDM encourages governments and investors to find marginal projects whose exact impact on emissions is easy to measure. Yet the biggest opportunities for “win–win” policies are those where the emissions impact is hardest to predict and where no rational CDM investor will tread. (Nor does it help that many CDM projects have no impact on emissions, which floods the market with CDM credits and discourages more costly investments that could actually make a difference.) A different system is needed. Rather than thousands of small CDM projects, efforts to engage the reluctant countries should focus on a small number of huge opportunities where there is large leverage on emissions and where the opportunity aligns with the administrative abilities of the host government. A reformed CDM can play a subsidiary role, but the real diplomatic effort should focus where leverage is greatest. Reluctant countries should compile their opportunities; declare the external resources they will need for each, and let enthusiastic countries compete for the privilege of playing a role. Eventually the reluctant nations will have to do more and spend their own resources on emission controls, but a big effort to seize “win–win” opportunities is the right way to start. Not only will it make a dent in emissions, but it will also establish a track record of credible engagement that will be needed for the future when global warming politics will get a lot tougher to manage and stiffer incentives will be needed—including bigger sticks to punish recalcitrant nations. In global warming, like most areas of international diplomacy, it is better to lead with positive engagement before bringing out the big sticks.

This step in the logic leads to one simple conclusion about emission controls. The tighter the screws on emissions the harder it will be to plan regulation according to exact targets and timetables. And the tighter the screws, the more that efforts by one government will depend on what others do as well. This helps explain some of the gridlock from Kyoto to Copenhagen. International negotiations have been organized mainly to encourage governments to coordinate around emission targets and timetables. But no government that is serious about making credible promises actually knows the emission levels that will emanate from its economy. The simple conclusion from this step in the logic is that international cooperation should be designed differently. It should revolve around what governments can credibly promise to implement. Moreover, cooperation should elicit contingent promises—that is, governments should outline what they will do on their own merits as well as the schedule of additional efforts they will adopt if other governments make comparable efforts. A more realistic sense of what enthusiastic and reluctant nations can really implement at home can guide serious efforts to design international cooperation that meshes with what governments will be willing and able to implement at home. That is Step 3.

Step 4, investing in innovation

Steps 4 and 5 are detours. I include them in this essay because ignoring them leads to a global warming plan that does not work over the long term and leaves the planet highly vulnerable.

Step 4 deals with technology. As the cost of emitting CO2 rises and as regulations tighten, companies and governments will know that they should find technologies that can lower the cost of compliance. Those built-in incentives for innovation go a long way, but not far enough. Really deep cuts in emissions will require radically new technologies but few companies can justify spending the resources on that kind of innovation because the benefits are so uncertain and difficult to internalize. So an active “technology policy” is needed.

Getting started on technology policy requires focusing on the countries that matter most. Luckily, that list is short: about 95 percent of innovative activity occurs in only ten countries.9 A big push is needed not only within these countries but also through collaboration between those governments. Increasingly, the market for technology is global. Good ideas in one country diffuse quickly, which means that individual countries will under-invest in new technology unless they are confident they can create new markets for innovation around the world. In the past there has been almost no serious international collaboration on technology policy. The world has experimented with some partial models—for example, international collaboration on large science experiments and the “peer review” that OECD conducts on science and innovation policy. As with emission controls, how every country tackles the innovation challenge is likely to vary with its own national circumstances. Even more than with emission controls, the innovative process does not lend itself to strict targets and timetables; outputs are unpredictable.

Technology policy has become a poor cousin of serious efforts to slow global warming. Nearly everyone agrees that massive innovation is needed. Oddly, very few studies actually examine the question that matters most for policy: how to design a big push on innovation. A growing number of advocates call for a “Manhattan project” on global warming but that model is exactly wrong for global warming. In the Manhattan project, the US crash program to develop nuclear weapons, there was just one customer (the US military); commercial competition was irrelevant and costs were no object. “Putting a man on the Moon,” another common refrain, followed the same model and is equally poorly suited for global warming. These are inspiring goals that signal the scale of the needed effort, but they are terrible metaphors for policy. Almost as dangerous are wild ideas for quickly and radically increasing R&D spending without any serious plan for how new money can be spent well. Ramping up spending too quickly will just raise the price of R&D without much affecting what really matters, which is innovative output.

Getting serious about technology policy starts with realizing just how dreadful governments have been over the last generation. From the early 1980s through 2008 world spending on energy technology innovation appears to have plummeted. There has been an uptick since 2008, notably in the US, but most of that mainly reflects a huge pulse of “stimulus” money that will soon disappear as governments grapple with their fiscal poverty and struggle to provide funding to other national projects that are politically more popular. As this blip in funding fades, what should be done? I argue that good answers to that question have been hidden by a series of fallacies about technology policy. One fallacy is that government is unable to do the job because it will squander resources on white elephants rather than the viable technologies. A second fallacy is that carbon markets will encourage and pay for technology innovation. In Potemkin markets, well-organized interest groups make sure there is not much money left over for other purposes; they channel most of the resources to themselves and invest it mainly with incumbent technologies. And carbon prices are so volatile the special grants of emission credits do not have a value that is reliable enough over the long term to finance the slow commercial gestation of new technology. The only serious way to fund technology innovation is with reliable funding, mainly from government, and credible guarantees that new technologies will find viable markets. In the US, especially, there has been a historical wariness about technology strategies because it is often assumed the nation’s record with government-led energy innovation is a string of unmitigated disasters. The real record is actually a lot better than commonly assumed, and looking outside energy there are many other useful models where the track record is even better. Government is essential and its track record with technology policy is encouraging. Dangers loom, of course, because an active technology policy can also become industrial policy. The right models—with clear sunrises and sunsets—can help avoid those well-known pitfalls.

Economists argue that technology policy is needed to overcome a market failure. That is true, but an equally important role for technology policy is to help manage a political failure. Governments under-invest in innovation because innovators are usually political orphans. Nearly always, the invention of a radically new way of doing things arrives on the scene with no natural political constituency. And the innovation creates many incumbents who are politically well organized and unfriendly to change. Technology policy helps fix these problems; it also helps build confidence that emission controls will not be impossibly costly to implement. All that reinforces the central task for policy, which is the adoption of credible emission controls that will pull new technologies into the market.

The problem of political orphans is getting slightly easier to solve for two reasons. One is the growing interest in green jobs—an area where politicians are making reckless claims about the prospects for job creation, but those claims help build a political coalition that so far has been supportive of spending on low-carbon innovation.10 The other is the possible merging of information technology (IT) with energy. The innovation model in IT and a few other areas such as biotechnology is based on “block-buster” inventions—that is, new ideas that spread rapidly and generate massive returns to innovators. The belief that energy is shifting to that mode of innovation makes it somewhat easier for private firms and governments to mobilize the resources needed for energy innovation. These are political arguments; whether a new dawn of green jobs or the integration of IT with energy are actually real remains to be seen. (I think most green jobs claims are largely baseless, and I doubt it will be easy to measure “green” versus “brown” job creation.) Politically, though, such arguments are changing the landscape and making it easier to muster the political support for innovation policy.

That is Step 4. A technology policy is essential to overcoming market and political failures. But it would not happen without good models for how government can be most effective.

Step 5, bracing for change

Step 5 is my other detour. Even a serious effort to control emissions is unlikely to stop global warming. The climate system and the energy system that emits CO2 are big, complicated systems that are laden with inertia. They are pointed in the wrong direction, and they would not change course easily. Worse, so far the most important emitters have not created a viable international scheme to coordinate policies to cut warming gases. Once such a system is in place, but the benefits of slower warming will be felt only after perhaps twenty years of sustained effort and another few decades will be needed actually to stop warming. Even more time will pass before the stock of CO2 declines decisively from its peak and warming abates. These timetables will be seen by experts, who have invested heavily in efforts to set “safe” goals for warming such as limiting warming to two degrees, as too pessimistic. (And technology wildcards, such as devices that can remove CO2 and other warming gases directly from the air, might indeed accelerate the ability to stop and reverse warming.) My sense is they are about as fast as serious regulatory and technology deployment efforts will run. And this optimistic scenario assumes that governments actually launch serious, prompt efforts to control emissions and invest in new technologies.

Even under the best scenarios the world is in for probably large changes in climate. Societies need to brace for the changes. For many years, this subject was taboo in most circles because many of the most ardent advocates for global warming policy feared that talking about the need to prepare for a warmer world would signal defeat. Worse, it might signal that warming was tolerable, and that might lead governments to lose focus on the central task of regulating emissions. It is much sexier to imagine bold schemes that stop global warming rather than the millions of initiatives that will be needed to cope with new climates. Yet the unsexy need to brace for change is unavoidable.

Humans are intelligent and forward-looking, and those qualities make them adaptive so long as they can anticipate the needed changes and have the resources required to adjust. Farmers, for example, can plant different seeds and switch to new crops. Real estate markets can adjust to the likely effects of rising sea levels and stronger storms that could inundate ocean-front properties. Water planners can anticipate rainfalls of different levels and variability. The central role for policy is to lubricate these natural human skills in adaptation. More timely information about climate impacts can help; more efficient markets for scarce resources such as water can be created; funding for infrastructures that are less sensitive to changing climates can be mobilized. For rich, capable societies, success in adaptation is hardly guaranteed but at least it is a familiar task.

Much tougher issues arise in less wealthy countries where climate-sensitive agriculture dominates the economy and people are already living on the edge. Small changes in climate can have a big human toll. When I began this project I expected to conclude that rich countries, which are most responsible for climate change, should create huge funds to help poor countries adapt. Instead, I have arrived at a much darker place. Such efforts are well meaning, but they are unlikely to make much difference. Adaptation does not arise as a discrete policy. It comes from within a society and its governing institutions, and there is very little that outsiders can do to help. Most so-called “adaptation projects”—for example, building sea walls or creating a national weather service to provide farmers with more useful climatic information to help them adapt—make no sense unless implemented within institutions that can actually deploy and utilize these resources efficiently. I will call these “adaptation-friendly contexts.” One of the hard truths about global warming is that these contexts are self-reinforcing. When they exist, the list of discrete adaptation projects where outsiders can be helpful is short because societies invest in adaptation on their own. When these contexts do not exist, adaptation spending is not very useful. Readers will recognize this problem as analogous to the problem of economic development. Foreign assistance for development can be extraordinarily important when applied under the right circumstances, but only a subset—perhaps a small subset—of countries actually enjoy those circumstances. The same is true for adaptation.

The Copenhagen Accord includes promises of massive new funding for adaptation, and it appears that most of those promises will be broken. More money can assuage guilty feelings that rich polluters feel, having imposed climate harms on poor societies that already have enough troubles. But more money, alone, probably will not do much to make those countries less vulnerable and to boost their welfare. This insight raises troubling questions of international justice. So far, most of the theories of international justice that have been applied to the climate problem have focused on how to divide the burden of controlling emissions; they have not much grappled with the more practical and immediate challenge of how the rich industrialized societies that are most responsible for the buildup of warming gases can help the most vulnerable societies cope with these inevitable changes in climate. My answer is that the rich countries need to be more diligent in controlling their emissions while, in tandem, working harder to facilitate adaptation-friendly contexts across the developing world. In practice, creating those contexts means investing more in the economic development. All of that is hard to do and in many developing countries, if not most, will not work perfectly.

If the news about adaption for humans is dark, the news for nature is even more troubling. Unlike humans, nature responds to changing circumstances mainly through natural selection. That means that a changing climate is likely to bring a lot of extinction to species that are already living on the edge while promoting hardier plants and critters such as weeds and cockroaches. The impacts will be felt not just in individual species but whole ecosystems. Avoiding these unwanted outcomes will require a more active human hand. Because humans can look ahead and behave strategically they can implement projects such as installing corridors between ecosystems so that plants and animals can more readily march to cooler climates. Through such efforts, humans might help steer nature away from unwanted nasty outcomes. If climate changes in extreme ways, this will turn humans into zookeepers. Huge areas of wild landscapes will be put under environmental receivership, and managing them will require human handling on a scale never imagined. Doing all this across nature will probably cost a lot more than people are willing to pay, and in many ecosystems human management may be worse than letting nature sort itself through the Darwinian method. The need for triage will appear. So far, barely any such discussion is under way. The last century has seen a sharp rise in international funding for nature, much of it managed by NGOs and focused on preserving gems of nature. In a world of changing climates, these NGOs will be on the front lines of nature’s triage. They will probably have a difficult time accepting this mission because zookeeping and triage run counter to their core historical missions, which center on protecting nature in its original state. The most successful international nature NGOs are steeped in a culture of protection—they buy lands, create parks, erect fences where possible, and do their best to keep humans away and to lighten the human footprint. Triage will require more or less the opposite strategy.

If all that is not dark enough, I also look at some worst case scenarios. Barely a month goes by without a publication of new research suggesting that climate could change more rapidly than previously expected. For example, there is striking news from glaciologists about possible more rapid melting of ice sheets as well as news from the Arctic about the unexpectedly rapid thinning of that ice cap. Once such changes are under way the effects on things that matter could be more horrendous than earlier thought. The unknown unknowns of global climate change might hold pleasant surprises or horrors. The evidence at the horror end of the spectrum is mounting.11

Thus I also argue that bracing for change also requires readying some emergency plans. Those will include intervening directly in the climate to offset some of the effects of climate change, which is also known as “geoengineering.” Volcanoes offer a model, for their periodic eruptions spew particles into the upper atmosphere that cool the planet for a time. Man-made efforts along the same lines might include flying airplanes in the upper atmosphere and sprinkling reflective particles that might crudely cool the climate.12 So far, most of the public discussion about geoengineering treats the option as a freak show of reckless Dr. Strangeloves tinkering with the planet. Yet it is hard to digest the most alarming scenarios from climate science without concluding that serious preparations are needed on the geoengineering front. I argue for a research program in this area so that some of the most viable options can be tested. I also argue that such a program needs to follow special rules such as transparency, publication of results, pre-announcement of tests, and careful risk assessments that focus on the possible side effects. That approach is needed so that if governments ever get to the stage where they might actually deploy geoengineering systems, a set of norms and practices are in place about how to treat these technologies. There are two big dangers with geoengineering. One is that the technology will be so controversial that the countries with the best scientists do not invest in testing the options and readying them in case of need. The other is that a desperate country will launch geoengineering without preparing for the side effects. A dozen or so nations probably already have the ability to deploy geoengineering and the list is growing. A race is on between building a responsible research program that can lay the foundation for good governance of geoengineering technologies and the desperate “hail Mary” pass of a country that could not stomach the extreme effects of warming and is disillusioned with the lack of serious efforts to stop global warming through regulation of emissions.

Step 6, a new international strategy

The sixth and final step is a redesign of the international diplomatic strategy. It will seem odd in an essay that is about overcoming the gridlock in international diplomacy to wait so long before a new diplomatic vision arrives fully on the scene. I have started with national policy because international agreements that do not align with national interests and capabilities are unlikely to be effective.

To develop a new international strategy we must understand, first, why diplomatic efforts so far have led to gridlock. My argument is that the diplomatic toolbox used over the last two decades is the wrong one for the job. That toolbox comes from experience in managing earlier international environmental problems, which have little in common with the costly, complicated regulatory challenges that arise with warming gases. Indeed, all of the canonical elements in that toolbox are wrong for global warming. Those elements include global agreements, which diplomats cherish because they believe they are more legitimate than smaller more exclusive accords. They include binding treaties, which most analysts wrongly think are more effective because governments always take binding law more seriously. And they include emission targets and timetables, which are a mainstay of environmental diplomacy because most diplomats and NGOs think targets and timetables are the best way to guarantee that governments actually deliver the environmental protection they promise. These conventional wisdoms are deeply ingrained in environmental diplomacy; many are rooted in the experience of the Montreal Protocol where targets were used effectively because the gases that were regulated were relatively easy to control and the regulations included safety valves in case firms discovered that new substitutes would not be ready in time. None of that history applies directly to regulation of CO2 since alternative energy systems are much harder to plan and install to exacting timetables.

An alternative approach starts with one central insight: effective international agreements on climate change will need to offer governments the flexibility to adopt highly diverse policy strategies. Instead of universal treaties, I suggest that cooperation should begin with much smaller groups—what international relations experts often call “clubs.”13 It should begin with non-binding agreements that are more flexible. And it should focus on policies that governments control rather than trying to set emission targets and timetables since emission levels are fickle and beyond government control. Cooperation challenges of this type are rare in international environmental diplomacy, but they are much more common in economic diplomacy where governments often try to coordinate their policies in a context where no government really knows exactly what it will be willing and able to implement. The closest analogies are with international trade and the model I offer draws heavily from the experience with the GATT and WTO.

The backbone of this new approach would be a series of contingent offers. Governments would outline what they are willing and able to implement as well as extra efforts that are contingent on what other nations offer and implement. Negotiations within the club would concentrate on the package of offers that are acceptable to participating nations. By working in a small group—initially about a dozen nations or fewer, as suggested in Figure 1.1—it would be easier to concentrate on which offers were genuine and to piece together a larger deal that takes advantage of the contingencies. As individual countries gain confidence that others will honor their commitments then they, too, will be willing to adopt more costly and demanding policies at home. As part of this process, enthusiastic nations would also scrutinize the many bids from reluctant nations and offer resources to those that were most promising. Early in the UNFCCC talks the Japanese government backed an idea called “Pledge and Review” that would have pursued this strategy—I thought it was a good idea then and I still support it. Sadly, most other nations did not pick it up because they have been too seized by the conventional wisdom of global agreements focused on targets and timetables rather than a better system of diplomacy focused on what countries could really implement.

Deals created in this small group would concentrate benefits on other club members—for example, a climate change deal might include preferential market access for low-carbon technologies and lucrative special linkages between emission trading systems in exchange for tighter caps on emissions. Concentrating benefits on other club members will create stronger incentives for participating governments to deepen their cooperation. Focusing cooperation on contingent offers, each club member will see its efforts multiplied, which will help ensure that the offers are not too modest. In time, this approach of offering benefits that are exclusive and contingent will make club membership more attractive to potential new members. Such club approaches often fare better than larger negotiations when dealing with problems, such as global warming, that are plagued by the tendency of governments to offer only the lowest common denominator. Clubs make it easier to craft contingent deals and channel more benefits to other members of the club, which creates stronger incentives for the deals to hold.

The logic of clubs underpins many efforts and proposals in recent years to focus on warming policy in forums that are smaller and more nimble than the UN. Those include the G20, the “Environmental 8,” the Major Economies Forum (MEF), and similar ideas. These are all good ideas; what is missing is a strategy that will make such smaller forums relevant. Governments that care most about slowing global warming need to invest in these small forums and focus their efforts on creating benefits that will entice other governments to do more. I am cautiously optimistic that such club approaches will regain favor in the wake of the troubles at Copenhagen, but I am not blind to the power of conventional wisdom. The conventional wisdoms that have created gridlock on global warming remain firmly in place and are hard to shake. Creating a club that works will require leaders who will make the first contingent offers that create incentives for other countries to act. The EU has not been a leader on this front because it is overly invested in the UN approach. Japan has not because it is too timid to swim against the current of conventional wisdom. And the US has not played the leader role because what America says these days on most matters is so volatile that it is not seen as credible. A smarter EU, a more credible US or a big move by China or India could be very helpful.

Clubs are a way to get started, but they are not the final word. Eventually the clubs must expand. Indeed, the global UNFCCC will remain as an umbrella under which many global efforts unfold. The advantage of starting with a club is that the smaller setting makes it easier to set the right norms and general rules to govern that expansion. In practice, this will be a lot easier than it seems because international emission trading can be a powerful force working in the same direction. With the right policies, the international trade in emission credits creates a mechanism for assigning prices to efforts. It rewards countries with strict policies by giving higher prices to their emission credits. Over the history of the GATT/WTO, the most powerful mechanism for compliance was the knowledge that if one country reneged on its promises, others could easily retaliate by targeting trade sanctions and removing privileges to punish the deviant. With the right pricing policies, emission trading could provide the same kinds of incentives.

There is no shortage of institutions already working on climate change. In fact, one of the defining characteristics of international legal institutions in this area is their high dispersion—rather than a single, integrated legal regime there is a “complex” of partially overlapping legal obligations.14 What is missing is a strategy focused on getting countries to make reliable promises about what they can and will implement. The central diplomatic task in the coming years will be to couple those national promises to the efforts that other nations will undertake so that, over time, each major country sees growing incentives to implement more effective policies to control emissions. I have drawn on models from international economic cooperation where these diplomatic challenges are much more familiar. Indeed, the challenges that climate diplomats face today are analogous to those that have defined much of the history of international efforts to create a rule-based system for advancing international trade. Those same models are the best guides for getting serious about global warming.

In some respects, the climate system is already evolving in the direction I advocate—not by design but through default. The UN efforts are stuck in gridlock, and that has left smaller clubs as one of the few places where progress is emerging. While that shift is encouraging, climate strategy by default will not solve the problem of global warming. For the club strategy to work it will require active efforts to build institutions and focus on practical policies. So far, there is not yet much evidence of that kind of heavy lifting. Hopefully this new book will offer a roadmap for the countries that care most about slowing global warming to lead the world in doing a better job of actually protecting the planet.

Notes

1 This essay is adapted from Victor (2011, Chapter 1).

2 To be sure, these marginal players can help slow the rate of warming and shift the most intense periods of warming by decades. A big effort to regulate strong but short-lived warming gases such as black carbon or methane can help slow the rate of warming, but there is no viable strategy for stopping warming altogether without a central focus on CO2. For multi-gas studies that explore such issues see, among many, notably Wigley et al. 2009; Ramanathan and Xu 2010; Ramanathan and Victor 2010.

3 This point has been made by many other scholars. For a brief but deeply historical view see Grübler et al., eds (1998).

4 See Stern (2007) and Nordhaus (2010) among many other studies.

5 This is an important area for better collaborative research between political scientists and international lawyers. For a recent review see Hafner-Burton et al. (2012).

6 This view that a technology-focused policy strategy can solve the political problem of climate change is one that persists. See for example Shellenberger et al. (2008). I am enormously sympathetic to the need for technology investments, as discussed below, but technologies strategies do not work unless they also include a market incentive—a “pull” from the market, such as through a carbon tax or regulatory requirements—that encourage adoption of the technology (see Victor, 2011, Chapter 6).

7 For more see Wara and Victor (2008).

8 For example, see World Bank (2009).

9 This assessment is based on R&D spending (inputs to innovation) and especially patent outputs. For more detail see Victor (2011).

10 For more on how smart green technology strategies can make it easier to manage problems like climate change see Chung (2011).

11 For a recent survey see Schiermeier (2011).

12 The geoengineering intelligentsia actually call this “solar radiation management (SRM)” because their definition of geoengineering is much broader and includes any large-scale intervention in the climate system. Here I will use the term in a narrow way to mean climate interventions that produce quick results, such as sprinkling reflective particles in the stratosphere to mimic the behavior of volcanoes. What matters is that these systems produce very rapid and large-scale climate impacts—that is why they are interesting to investigate as options in case a climate emergency appears on the horizon and why they are also scary. Whenever one messes with a complex system in ways that produce large-scale and rapid change it is hard to predict all the consequences.

13 The relevant theory is rooted in the economic theory of clubs, notably Buchanan (1965); see also Keohane and Victor (2011).

14 For a more detailed assessment see Keohane and Victor (2011).

References

Boden, T. A., G. Marland, and R. J. Andres. 2010. “Global, Regional, and National Fossil-Fuel CO2 Emissions.” Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, US Department of Energy, Oak Ridge, TN. doi 10.3334/CDIAC/00001_V2010.

Buchanan, James M. 1965. “An Economic Theory of Clubs.” Economica 32(125): 1–14.

Chung, Suh-Yong. 2011. “Green Technology: New Environmental Costs?” International Conference on Practising Green Growth, Paris, May 30, 2011.

Grübler, Arnulf, N. Nakicenovic, and A. McDonald, eds. 1998. Global Energy Perspectives. Cambridge, UK and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Hafner-Burton, Emilie, David G. Victor, and Yonatan Lupu. 2012. “Political Science Research On International Law: The State of the Field.” American Journal of International Law 106(1): 47–97.

Keohane, Robert O. and David G. Victor. 2011. “The Regime Complex for Climate Change.” Perspectives on Politics 9(1): 7–23.

Nordhaus, William D. 2010. “Economic Aspects of Global Warming in a Post-Copenhagen Environment.” PNAS 107(24): 11721–11726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005985107.

Ramanathan, Veerabhadran and David G. Victor. 2010. “To Fight Climate Change, Clear the Air,” New York Times, November 27, p. WK-9, online, available at: www.nytimes.com/2010/11/28/opinion/28victor.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0.

Ramanathan, Veerabhadran and Yangyang Xu. 2010. “The Copenhagen Accord for Limiting Global Warming: Criteria, Constraints and Available Avenues.” PNAS 107(18): 8055–8062.

Schiermeier, Quirin. 2011. “Extreme Measures: Can Violent Hurricanes, Floods and Droughts be Pinned on Climate Change?” Nature 477: 148–149.

Shellenberger, Michael, T. Nordhaus, J. Navin, T. Norris, and A. Van Noppen. 2008. “Fast, Clean and Cheap: Cutting Global Warming’s Gordian Knot.” Harvard Law and Policy Review 2(1): 93–118.

Stern, Nicholas. 2007. The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review. Cambridge, UK and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change). 2010. “National Inventory Submissions 2010,” Annex I Party GHG Inventory Submissions, online, available at: http://unfccc.int/national_reports/items/1408.php.

Victor, David G. 2011. Global Warming Gridlock: New Strategies for Protecting the Planet. Cambridge, UK and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Wara, Michael W. and David G. Victor. 2008. A Realistic Policy on International Carbon Offsets. Working Paper #74. Program on Energy and Sustainable Development, Stanford University, April.

Wigley, T. M. L., L. E. Clarke, J. A. Edmonds, H. D. Jacoby, S. Paltsev, H. Pitcher, J. M. Reilly, R. Richels, M. C. Sarofim, and S. J. Smith. 2009. “Uncertainties in Climate Stabilization.” Climatic Change 97(1/2): 85–121.

World Bank. 2009. Climate Change and the World Bank Group, Phase I: An Evaluation of World Bank Win–win Energy Policy Reforms. Independent Evaluation Group. Washington DC: IBRD/The World Bank.