Chapter 13

Using Mindfulness to Combat Anxiety, Depression and Addiction

In This Chapter

![]() Finding out about depression and anxiety

Finding out about depression and anxiety

![]() Discovering ways in which mindfulness reduces depression and anxiety

Discovering ways in which mindfulness reduces depression and anxiety

![]() Exploring specific techniques

Exploring specific techniques

“You are not your illness.”

Depression, anxiety and addiction present serious challenges in our society. According to the World Health Organization, depression is the planet’s leading cause of disability, affecting 121 million people worldwide. About one in six people suffer from clinical depression at some point in their lives. About one in fifty people experience generalised anxiety at some point in their lives – feeling anxious all day.

Medical evidence suggests that mindfulness is very powerful in helping people with recurrent depression, and studies with anxiety and addiction look extremely promising too. If you suffer from any of these conditions, following the mindfulness advice in this chapter can really help you.

Dealing Mindfully with Depression

Of all mental health conditions, recurring depression has most clearly been shown to respond to mindfulness. If the body of evidence continues to grow, mindfulness may go on to become the standard treatment for managing depression all over the world. This section explains what depression is and why mindfulness seems to be so effective for those who have suffered from several bouts of depression.

Understanding depression

Depression is different to sadness.

Sadness is a natural and healthy emotion that everyone experiences from time to time. If something doesn’t go the way you expect, you may feel sad. The low mood may linger for a time and affect your thoughts, words and actions, but not to a huge extent.

Depression is very different. When you’re depressed, you just can’t seem to feel better, no matter what you try.

Unfortunately, some people still believe that depression isn’t a real illness. Depression is a real illness with very real symptoms.

According to the NHS, if you have an ongoing low mood for most of the day every day for two weeks, you’re experiencing depression and you need to visit your doctor. The symptoms of depression can include:

- A low, depressed mood

- Feelings of guilt or low self-worth

- Disturbed sleep

- A loss of interest or pleasure

- Poor concentration

- Changes to your appetite

- Low energy

Understanding why depression recurs

Depression has a good chance of being a recurring condition, and to understand why, you need to understand the two key factors that cause mild feelings of sadness to turn into depression:

- Constant negative thinking (rumination). This is the constant, repetitive use of self-critical, negative thinking to try to change an emotional state. You have an idea of how things are (you’re feeling sad) and how you want things to be (feeling happy, relaxed or peaceful). You keep thinking about your goal and how far you are from your desired state. The more you think about this gap, the more negative your situation seems and the further you move away from your desired emotion. Unfortunately, thinking in this way – trying to fix the problem of an emotion – only worsens the problem and leads to a sense of failure as depression sets in. Rumination doesn’t work, the reason being that emotions are part of being human. To try to fix or change emotions by simply thinking about what you want doesn’t work. Rumination is a hallmark of the doing mode of mind, explained in Chapter 5.

- Intensely avoiding negative thoughts, emotions and sensations (experiential avoidance). This is the desire to avoid unpleasant sensations. But the process of experiential avoidance feeds the emotional flame rather than reducing or diminishing the emotion. Running away from your emotions makes them stronger.

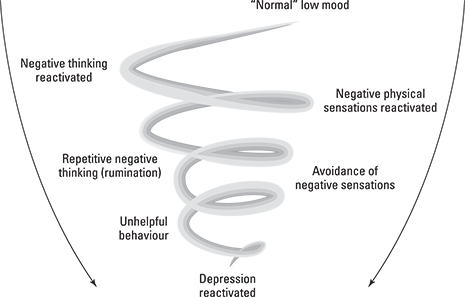

When you first suffer from depression, you experience negative thoughts, a negative mood and sluggishness. When this occurs, you create a connection between these thoughts, feelings and bodily sensations. Even when you feel better, the underlying connections are still there, lying dormant. Then, when by chance you feel a little sad, as everyone does, you begin to think, ‘Here we go again. Why is this happening to me? I’ve failed,’ and so on. The negative thoughts recur. This triggers the negative moods and low levels of energy in the body, which creates more negative thinking. The more you try to avoid your negative thoughts, emotions and sensations, the more powerful they become. This is called the downward mood spiral, as shown in Figure 13-1.

Using mindfulness to change your relationship to low mood

One of the key ways in which depressive relapse occurs and is sustained is through actively trying to avoid a negative mood. Mindfulness invites you to take a different attitude towards your emotion. Depression is unpleasant, but you see what happens if you approach the sensation with kindness, curiosity, compassion and acceptance. This method is likely to be radically different to your usual way of meeting a challenging emotion. Here are some ways of changing your relationship with your mood and thereby transforming the mood itself.

Figure 13-1: Downward mood spiral.

When you experience a low mood, try one of these exercises as an experiment and see what happens:

- Identify where in your body you feel the emotion. Is your stomach or chest tight, for example? What happens if you approach that bodily sensation, whatever the sensation is, with kindness and curiosity? Can you go right into the centre of the bodily sensation and imagine the breath going into and out of the sensation? What effect does that have? If you feel too uncomfortable doing that, how close can you get to the unpleasant feeling in your body? Try playing with the edge of where you’re able to maintain your attention in your body, neither pushing too hard nor retreating away. Try saying to yourself: ‘It’s okay, whatever I feel, it’s okay, let me feel it.’

- See yourself as separate from the mood, thought or feeling. You’re the observer of the sensation, not the sensation itself. Try stepping back and looking at the sensation. When you watch a film, you have a space between yourself and the screen. When you watch the clouds going by, a space separates you from the clouds. A space also exists between you and your emotions. Notice what effect this has, if any.

- Notice the kinds of thoughts you’re thinking. Are they self-critical, negative thoughts, predicting the worst, jumping to conclusions? Are the thoughts repeating themselves again and again? Bring a sense of curiosity to the patterns of thought in your mind.

- Notice your tendency to want to get rid of the emotion. See if you can move from this avoidance strategy towards a more accepting strategy, and observe what effect this has. See whether you can increase your acceptance of your feelings by 1 per cent – just a tiny amount. Accept that this is your experience now, but won’t be forever, so that you can temporarily let go of the struggle, even slightly, and see what happens.

- Try doing a three-minute breathing space as described in Chapter 7. What effect does this have? Following the breathing space, make a wise choice as to what is the most helpful thing for you to do at the present moment to look after yourself.

- Recognise that recurring ruminative thinking and having a low mood are a part of your experience and not part of your core being. An emotion arises in your consciousness and at some point diminishes again. Adopting a de-centred, detached perspective means you recognise that your low mood isn’t a central aspect of your self – of who you are.

Discovering Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT)

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) is an eight-week group programme based on the mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) course described in Chapter 9. The MBSR course has been found to be very helpful for people with a range of physical and psychological problems. MBCT was specifically adapted for those who’ve suffered repeated episodes of depression. Research so far has proven that MBCT is 50 per cent more effective than the usual treatment for those suffering from three or more episodes of depression.

MBCT is a branch of a more general form of therapy called cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which holds that thoughts, feelings and actions are intimately connected. The way you think affects the way you feel and the activities you engage in. Conversely, the way you feel or the activities you undertake affect the way you think, as shown in Figure 13-2.

Figure 13-2: The relationship between thoughts, feelings and activities.

Traditional CBT encourages you to challenge unrealistic negative thoughts about yourself, others or the world. (Discover more in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy For Dummies by Rhena Branch and Rob Willson (Wiley).) Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy takes a slightly different approach. Rather than deliberately considering alternative thoughts, you move towards your unpleasant thoughts, emotions and physical sensations in a more de-centred, kind, curious and compassionate way – in other words, mindfully. The emphasis isn’t on changing the experience but on being with the experience in a different way. You develop the ability to do this through mindfulness meditation.

If you want to do the MBCT course on your own using this book, you can follow the eight-week MBSR course described in Chapter 9, and in addition do the activities in this chapter. This isn’t the same as doing a course with a group and a professional teacher, but gives you an idea of what to expect and certainly may help you.

Pleasant and Unpleasant Experiences

In everyday life, you experience a whole range of different experiences. They can all be grouped into pleasant, unpleasant and neutral experiences. Pleasant experiences are the ones you enjoy, like listening to the birds singing or watching your favourite television programme. Unpleasant experiences may include having to sit in a traffic jam or dealing with a difficult customer at work. Neutral experiences are the ones you just don’t even notice, like the different object in the room you’re in at the moment, or the taste of the tea or coffee you’re drinking. Mindfulness encourages you to become curious about all aspects of these experiences.

You can probe your experiences through the following exercise, which is normally done over two weeks:

The following week, repeat the exercises, but this time for an unpleasant experience each day. Remember, you don’t need to have very pleasant or unpleasant experiences – even a small, seemingly insignificant experience will suffice.

The purpose of this exercise is to:

- Help you to see that experiences aren’t one big blob. You can break down experiences into thoughts, feelings and bodily sensations. This makes difficult experiences more manageable rather than overwhelming.

- Notice your automatic, habitual patterns, which operate without you even knowing about them normally. You learn how you habitually grasp onto pleasant experiences with a desire for them to continue, and how you push away unpleasant experiences, called experiential avoidance, which can end up perpetuating them.

- Learn to become more curious about experiences instead of just judging experiences as good or bad, or ones you like or dislike.

- Encourage you to understand and acknowledge your unpleasant experiences rather than just avoid them.

Interpreting thoughts and feelings

You can do this visualisation exercise sitting or lying in a comfortable position:

- Imagine you’re walking on one side of a familiar road. On the other side of the road you see a friend. You call out his name and wave, but he doesn’t respond. Your friend just keeps on walking into the distance.

- Write down your answers to the following questions:

- What did you feel in this exercise?

- What thoughts did you have?

- What physical sensations did you experience in your body?

If you think, ‘Oh, he’s ignored me. I don’t have any friends,’ you’re more likely to feel down, and perhaps your body may slump. If you think, ‘He couldn’t hear me. Oh well, I’ll catch up with him later,’ you’re unlikely to feel affected by the situation. The main purpose of the exercise is to show that your interpretation of a situation generates a particular feeling, rather than the situation itself.

Almost all people have a different response to this exercise, because they have a different interpretation of the imagined event. If you’re already in a low mood, you’re more likely to interpret the situation negatively. Remember: thoughts are interpretations of reality, influenced by your current mood. Don’t consider your thoughts to be facts, especially if you’re in a low mood. Thoughts are just thoughts, not facts.

Combating automatic thoughts

Mindfulness encourages you to recognise and deal with negative automatic thoughts that can prolong depression or cause it to worsen.

Consider the following statements (adapted from Kendall and Hollon’s ‘Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire’, Cognitive Therapy and Research, 1980):

- I feel as if I’m up against the world.

- I’m no good.

- I’ll never succeed.

- No one understands me.

- I’ve let people down.

- I don’t think that I can go on.

- I wish I were a better person.

- I’m so weak.

- My life’s not going the way I want it to.

- I’m so disappointed in myself.

- Nothing feels good anymore.

- I can’t stand this anymore.

- I can’t get started.

- Something’s really wrong with me.

- I wish I were somewhere else.

- I can’t get things together.

- I hate myself.

- I’m worthless.

- I wish I could just disappear.

- I’m a loser.

- My life is a mess.

- I’m a failure.

- I’ll never make it.

- I feel so helpless.

- My future is bleak.

- It’s just not worth it.

- I can’t finish anything.

How much would you believe these thoughts right now if any one of them popped into your head? How much would you believe them if any one of them popped into your head when you were in your lowest mood? These thoughts are attributes of the illness called depression, and aren’t to do with your true self.

By considering depression in a detached way, you become more detached from the illness. You see depression as a human condition rather than something that affects you personally and almost no one else. You see depression as a condition that’s treatable through taking appropriate steps.

Alternative viewpoints

Alternative viewpoints are the different ways in which you can interpret a particular situation or experience.

Consider the following scenario: You’ve just been criticised by your boss for your work, and you feel low. You walk past one of your colleagues and are about to say something to him, and he says he’s really busy and can’t stop. Write down your thoughts and feelings.

Now consider a different scenario: Your boss has just praised you for doing an excellent job. You walk past one of your colleagues and are about to say something to him, and he says he’s really busy and can’t stop. Write down your thoughts and feelings.

You probably found very different thoughts and feelings in the two different circumstances. By understanding that your thoughts and feelings are influenced by your interpretation of a situation, you’re less likely to react negatively. Mindfulness allows you to become more aware of your thoughts and feelings from moment to moment, and offers you the choice to respond to a situation in a different way, knowing that your thoughts are just thoughts, or interpretations, rather than facts.

De-centring from difficult thoughts

Practise the three-minute breathing space meditation (explained in Chapter 7) and then ask yourself some or all the following questions. Doing so helps you to de-centre or step back from your more difficult thoughts and helps you to become more aware of your own patterns of mind. The questions are:

- Am I confusing a thought with a fact?

- Am I thinking in black and white terms?

- Am I jumping to conclusions?

- Am I focusing on the negative and ignoring the positive?

- Am I being perfectionist?

- Am I guessing what other people are thinking?

- Am I predicting the worst?

- Am I judging myself or others overly harshly?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of thinking in this way?

- Am I taking things too personally?

Listing your activities

Now list activities that give you a sense of mastery or pleasure. Activities that offer a sense of mastery are those that are quite challenging for you, such as tidying up a cupboard, making a phone call you’ve been avoiding, or forcing yourself to get out of the house to meet a friend or relative. Activities that offer pleasure may include having a hot bath, watching a film or going for a gentle stroll.

When you feel stressed or low in mood, choose a ‘mastery’ or ‘pleasure’ activity. Prior to making your choice, carry out the three-minute breathing space meditation to help bring mindfulness to the experience.

Making wise choices

When experiencing a low mood, a depressing thought, a painful sensation or a stressful situation, practise the three-minute breathing space and choose what to do next, which may be:

- Mindful action. Go back to doing what you were doing before, but in this wider, more spacious, being mode of mind (Chapter 5 explains a being mode of mind). Do each action mindfully, perhaps breaking the activity into small, bite-size chunks. The shift may be very small and subtle in your mind, but following the breathing space, you’ll probably feel different.

- Being mindful of your body. Emotions manifest in your physical body, perhaps in the form of tightness in your jaw or shoulders. Mindfulness of body invites you to go to the tension and feel the sensations with an open, friendly, warm awareness, as best you can. You can breathe into the sensation, or say ‘opening, acknowledging, embracing’ as you feel the uncomfortable area. You’re not trying to get rid of the sensations, but discovering how to be okay with them when the sensations are difficult or unpleasant.

- Being mindful of your thoughts. If thoughts are still predominant following the breathing space, focus your mindful awareness onto what you’re thinking. Try to step back, seeing thoughts as mental events rather than facts. Try writing down the thoughts, which helps to slow them down and offers you the chance to have a clear look at them. Reflect on the questions listed in the section ‘De-centring from difficult thoughts’. Bring a sense of curiosity and gentleness to the process if you can. In this way, you’re trying to create a different relationship to your thoughts, other than accepting them as 100 per cent reality no matter what pops up in your head.

- A pleasant activity. Do something pleasant like reading a novel or listening to your favourite music. While engaging in this activity, primarily engage your attention on the activity itself. Check in to notice how you’re feeling emotionally and how your body feels, and be mindful of your thoughts from time to time. Try not to do the activity to force any change in mood, but instead do your best to acknowledge whatever you’re experiencing.

- A mastery activity. Choose to do something that gives you a sense of mastery, no matter how small, such as washing the car, going for a swim or baking a cake. Again, give the activity itself your full attention. Notice whether you’re trying to push your feelings out, going back to habitual doing mode (Chapter 5), and instead allow yourself to accept your feelings and sensations as best you can, which is being mode (Chapter 5). Bring a genuine sense of curiosity to your experience as you go about your activity.

Using a depression warning system

Writing out a depression warning system is a good way of nipping depression in the bud rather than letting it spiral downwards. Write down:

- The warning signs you need to look out for when depression may be arising in you, such as negative thinking, oversleeping or avoiding meeting friends. You may want to ask someone close to you to help you do this.

- An action plan of the kind of things you can do that are helpful, such as meditation, yoga, walking or watching a comedy, and make a note of the kind of things that would be unhelpful, too, that you need to try to avoid if you can (perhaps changing eating habits, negative self-talk or working late).

Calming Anxiety: Let It Be

Anxiety is a natural human emotion characterised by feelings of tension, worried thoughts, and physical changes like increased blood pressure. You feel anxious when you think that you’re being threatened. Fear is part of your survival mechanism – without feeling any fear at all, you’re likely to take big risks with no concern about dangerous consequences. Without fear, walking right on the edge of a cliff would feel no different to walking in the park – not a safe position to be in!

This section looks at how mindfulness can help with managing your anxiety and fear, whether the feelings appear from time to time or whether you have a clinical condition such as generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), where you feel anxious all the time.

Feel the fear … and make friends with it

Eliminating fearful thoughts isn’t easy. The thoughts are sticky, and the more you try and push them out, the stronger the worries and anxieties seem to cling on. In this way, you can easily get into a negative cycle in which the harder you try to block out the negatives, the stronger they come back.

Mindfulness encourages you to face up to all your experiences, including the unpleasant ones. In this way, rather than avoiding anxious thoughts and feelings, which just makes them stronger and causes them to control your life, you begin to slowly but surely open up to them, in a kind and gentle way, preventing them building up out of proportion.

Perhaps this analogy may help. Imagine a room filling up with water. You’re outside the room trying to keep the door closed. As more and more water builds up inside the room, you need to push harder and harder to keep the door shut. Eventually you’re knocked over, the door flings open and the water comes pouring out. Alternatively, you can try opening the door very slowly at first, instead of pushing the door shut. As you keep opening the door, you give the water a chance to leave the room in a trickle rather than a deluge. Then you can stop struggling to keep the door shut. The water represents your inner anxious thoughts and feelings, and the opening of the door is turning towards the difficult thoughts and feelings with a sense of kindliness, gentleness and care, as best you can.

Using mindfulness to cope with anxiety

If you worry a lot, the reason for this is probably to block yourself from more emotionally distressing topics. For example, you may be worrying whether your son will pass his exams, but actually your worry-type thoughts are blocking out the actual feeling of fear. Although the worry is unpleasant and creates anxiety, the thoughts keep you from feeling deeper emotions. However, until you open up to those deeper emotions, the worry continues.

Worry is an example of experiential avoidance, described earlier in the chapter. Mindfulness trains you to become more open and accepting of your more challenging emotions, with acknowledgement, curiosity and kindness. Mindfulness also allows you to see how you’re not your emotions, and that your feelings are transient, and so it helps you to reduce anxiety. Mindfulness encourages you to let go of worries by focusing your attention on the present moment.

Here’s a mindful exercise for anxiety:

- Get comfortable and sit with a sense of dignity and poise on a chair or sofa. Ask yourself: ‘What am I experiencing now, in the present moment?’ Reflect on the thoughts flowing through your mind, emotions arising in your being, and physical sensations in your body. As best you can, open up to the experiences in the here and now for a few minutes.

- Place your hand on your belly and feel your belly rising and falling with your breath. Sustain your attention in this area. If anxious thoughts grasp your attention, acknowledge them but come back to the present moment and, without self-criticism if possible, focus back on the in- and out- breath. Continue for a few minutes.

- When you’re ready, expand your awareness to get a sense of your whole body breathing, with wide and spacious attention as opposed to the focused attention on the breath alone. If you like, imagine the contours of your body breathing in and out, which the body does, through the skin. Continue for as long as you want to.

- Note your transition from this mindfulness exercise back to your everyday life. Continue to suffuse your everyday activities with this gentle, welcoming awareness, just to see what effect mindful attention has, if any. If you find the practice supportive, come back to this meditation to find some solace whenever you experience intrusive thoughts or worries.

Being with anxious feelings

If you want to change anxiety, you need to begin with the right relationship with the anxiety, so you can be with the emotion. Within this safe relationship, you can allow the anxiety to be there, neither suppressing nor reacting to it. Imagine sitting as calmly as you can while a child is having a tantrum. No tantrum lasts forever, and no tantrum stays at exactly the same level. By maintaining a mindful, calm, gentle awareness, eventually and very gradually the anxiety may begin to settle. And even if it doesn’t go away, by sitting calmly next to it, your experience isn’t quite such a struggle.

- Observe how you normally react when anxiety arises; or if you’re always anxious, notice your current attitude towards the emotion.

- Consider the possibility of taking a more mindful attitude towards the anxiety.

- Feel the anxiety for about a minute with as much kindness and warmth as you can, breathing into it.

- Notice the colour, shape and texture of the feeling. What part of your body does it manifest in? Does the intensity of the sensation increase or decrease with your mindful awareness? Explore the area somewhere between retreating away from and diving into the anxiety, and allow yourself to be fascinated by what happens on this edge with your kindly, compassionate awareness.

- Watch the feeling as you may look at a beautiful tree or flower, with a sense of warmth and curiosity. Breathe into the various sensations and see the sensations as your teacher. Welcome the emotion as you may welcome a guest, with open arms.

This isn’t a competition to go from Steps 1 to 5 but is a process, a journey you take at your own pace. Step 1 is just as important, significant and deep as Step 5. Remember that these steps are a guide: move into the anxiety, or whatever the emotion is, as you see fit. Trust in your own innate wisdom to guide your inner journey.

Overcoming Addiction

An addiction is a seemingly uncontrollable need to abuse a substance like drink or drugs or to carry out an activity like gambling. Addictions interfere with your life at home, work or school, where they cause problems.

If you’re suffering from addiction, remember that you’re not alone. In the USA, for example, 23 million are addicted to alcohol or other drugs. And over two-thirds of people who suffer from addiction abuse alcohol.

The good news is, help is available. If you’ve tried and failed at overcoming your addiction, don’t give up. There’s hope, with all the support out there. Mindfulness is one of many ways to overcome addiction.

- Do you use more of the substance or participate in the activity more now than in the past?

- Do you experience urges or withdrawal symptoms when you don’t have the substance or activity?

- Do you ever lie to others about your use of the substance or your behaviour?

If the answer is yes, consider consulting a health professional for a more accurate evaluation and appropriate advice. A health professional can refer you to all sorts of support – many organisations can help in treating addiction. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and motivational enhancement therapy (MET) have been found to be very effective treatments.

Understanding a mindful approach to addiction

Once you’re addicted, your actions are the opposite of mindful: they’re automatic. This example describes a process that happens almost unconsciously each time you smoke a cigarette:

- You’re sitting at work on your desk and you feel a bit lethargic and tired.

- You feel the urge to smoke a cigarette. It’s actually a physical sensation in your body, but usually you don’t know where the sensation is in your body.

- You immediately think: ‘I need to smoke.’ (You don’t often consciously register this thought – it just happens in your brain.)

- You very quickly find yourself standing up and walking out of the building with the packet of cigarettes and a lighter in your hands (usually without awareness – a conscious choice is rarely made).

- The act of taking a cigarette out, lighting it and drawing in the smoke happens quickly and automatically (you may be lost in other thoughts).

- The urge is satisfied for now and the lethargy gone. You’re rewarded with a feeling of pleasure (dopamine is released in your brain). The cycle repeats again in a few hours.

Mindfulness offers you a way to identify the thoughts and emotions that are driving your addiction, and gives you a choice rather than just the automatic compulsion and action of depending on the addictive behaviour.

You discover that just because you have an urge to do something doesn’t mean you have to do it. You can just experience the urge until it passes.

Discovering urge surfing: The mindful key to unlocking addiction

One brilliant way of managing the urges that arise in addiction is called urge surfing. It’s a different way of meeting the reactive behaviour of addiction. Acting on strong cravings, when in an automatic pilot mode, doesn’t help you in the long term. By urge surfing, you don’t have to act on the urge or craving that you experience.

- Find a comfortable posture. You can sit, lie down, or even walk slowly – whatever you prefer. See whether you can relax your body a little and let go of any areas of tension. Begin by taking a deep breath and slowly breathing out.

- Notice that you have an urge to smoke, drink, gamble or whatever else it is for you.

- Be mindful of your body. Turn your attention to your physical bodily sensations. Where do you feel this urge in your body? Is it in one particular place or is it all over your body? What’s does the urge actually feel like?

- Be mindful of your thoughts. Notice and acknowledge the thoughts that are arising for you right now. Is it a familiar pattern of thoughts? Are they negative or judgemental thoughts? See whether you can step back from those thoughts, as if you’re an observer of the experience, rather than getting too caught up in the thoughts, if you can. Watch the thoughts like bubbles floating away.

- Be mindful of your feelings. Notice the feeling of the urge. The feeling may be very uncomfortable. That doesn’t make it bad or good – it’s just the nature of the feeling. Notice your judgement of ‘I like this experience’ or ‘I don’t like this experience’. Remember that the feeling isn’t dangerous or threatening in itself.

- Allow the experience to be as it is. See whether you can be with the experience without a need to get rid of it or to react to it by engaging in the behaviour that’s not helpful for you. Just practise being with the experience, the urge, the craving, the compulsion, in the present moment.

- Notice how the urge is changing. Perhaps the urge is increasing or decreasing for you. Maybe it’s staying just the same.

- If the urge is increasing, imagine a wave in the ocean approaching a beach. The waves rises higher and higher. But once it reaches its peak, it begins to come down again. Imagine your urge is like the wave. It’ll continue to grow in intensity but will then naturally go down again. It won’t keep growing forever. See whether you can just be present with the urge as it rises and falls. Ride the wave. You may even like to imagine yourself surfing the wave, the urge. Make use of your breathing. Keep ‘surfing that urge’. Perhaps see your breath like a surf board that supports you as you surf the wave of your urge.

- Notice how you’ve managed to surf this urge for all this time. This tool is always available for you, no matter how strong your urge or however intense your emotion or whatever thoughts arise for you.

Think of your urge like a tantrum that a child has. If you give the child a sweet, they’ll quieten down. But they’ve learnt to be rewarded for screaming. So before long they’ll have another tantrum. So what’s the solution? Just to be nice to them, but don’t to give them any sweets. Eventually the tantrum will stop. The next time they start screaming, if , again, you just hold them or hug them but don’t give them any sweets, the tantrum will end sooner. Eventually they’ll stop having tantrums altogether. Being kind to the child without giving them sweets is like being mindful of your urge without satisfying your urge.

- Get enough sleep. Aim for around eight hours if possible.

- Mediate daily.

- Exercise. Even a few minutes of walking is a great idea. You don’t have to be too intensive. Make it mindful walking to make it even more powerful.

- Slow down your breathing to four to six full breaths a minute – that can boost your willpower when you need it.

Managing relapse: Discovering the surprising secret for success

As someone once told me: ‘I’ve been a smoker for 20 years. I’ve given up hundreds of times.’

Most people who want to give up an addiction are able to stop for a short period, but in a moment of difficulty or mindlessness they begin using the object of their addiction again. This is to be expected. Everyone’s human and will mistakenly go back to the drug, drink or whatever.

How do you treat yourself when you have a relapse? Most people think that if they’re hard on themselves when they accidently relapse, they’ll get better. In fact, amazingly, the opposite has been found to be true in research.

Studies have found one of secrets of those that manage to give up long term: self-compassion. For example, people addicted to alcohol were less likely to have a major relapse if they were more forgiving of themselves when they had a drink.

The more kind and forgiving you can be with yourself when you relapse, the more likely it is that the relapse be a one-off. But if you beat yourself up, thinking, ‘Oh, I’m such an idiot. I can’t even give up drinking. I’ll never do it,’ the worse you feel. And the worse you feel, the more you feel the need to find some false comfort in your addiction.

This is a powerful approach if you’re dealing with an addiction. When you do manage to give up, let’s say a drug, for a few days, congratulate yourself each day. And when you end up relapsing on a bad day, tell yourself that you’ve made a one-off mistake and can go back to being drug-free again. Remind yourself that you’ve had four days of no drugs and one day having taken the drug. That’s four out of five – pretty good!

See whether you can manage a few more days without the substance – see whether you can sit with that urge a bit longer. See whether you can take the time to meditate, perhaps simply feeling your breathing, for a couple more minutes today. Be extra nice to yourself.

If you think that you suffer from a medical condition, please ensure that you visit your doctor before following any advice here. If you currently suffer from depression as diagnosed by a health professional, wait until the worst of the illness is over and you’re in a stronger position to digest and practise the mindfulness exercises in this chapter. Often mindfulness can work well together with other therapy or medication – again check with your doctor before you begin, so he can best advise and support you.

If you think that you suffer from a medical condition, please ensure that you visit your doctor before following any advice here. If you currently suffer from depression as diagnosed by a health professional, wait until the worst of the illness is over and you’re in a stronger position to digest and practise the mindfulness exercises in this chapter. Often mindfulness can work well together with other therapy or medication – again check with your doctor before you begin, so he can best advise and support you. Take a sheet of paper, or use your journal, and create four columns. Label them ‘experience’, ‘thoughts’, ‘feelings’, ‘bodily sensations’. Under each column heading, write down one experience each day that you found to be pleasant. Write down the thoughts that were going through your head, the feelings you experienced at the time, and how your body felt under the appropriate columns. Continue this each day for a whole week.

Take a sheet of paper, or use your journal, and create four columns. Label them ‘experience’, ‘thoughts’, ‘feelings’, ‘bodily sensations’. Under each column heading, write down one experience each day that you found to be pleasant. Write down the thoughts that were going through your head, the feelings you experienced at the time, and how your body felt under the appropriate columns. Continue this each day for a whole week. Anxiety and panic can be due to a combination of factors, including your genes, the life experiences you’ve had, the current situation you’re in, and whether you’re under the influence of drugs, including caffeine.

Anxiety and panic can be due to a combination of factors, including your genes, the life experiences you’ve had, the current situation you’re in, and whether you’re under the influence of drugs, including caffeine. Listen to the urge surfing meditation (Track 21). The steps when you have an urge are:

Listen to the urge surfing meditation (Track 21). The steps when you have an urge are: Try reflecting on what you really want when you’re in the midst of your craving. Usually it’s not the substance or behaviour you’re craving. Maybe you’re feeling lonely or stressed? Or maybe you want freedom from circumstances or emotions at this time?

Try reflecting on what you really want when you’re in the midst of your craving. Usually it’s not the substance or behaviour you’re craving. Maybe you’re feeling lonely or stressed? Or maybe you want freedom from circumstances or emotions at this time?